This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Saravask (talk | contribs) at 04:18, 21 January 2006 (→Geography and climate: fix lk). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 04:18, 21 January 2006 by Saravask (talk | contribs) (→Geography and climate: fix lk)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)Template:India state infobox Kerala (IPA: ; Malayalam: കേരളം — Keralam) is a state on the southwestern tropical Malabar Coast of India. Kerala borders Tamil Nadu and Karnataka to the east and northeast and the Indian Ocean islands of Lakshadweep and the Maldives to the west. With a population of around 3.18 crore (31.8 million) and 819 persons per km, Kerala is among India's most densely populated regions. A 73-year life expectancy and a 91% literacy rate also make Kerala its healthiest and most educated state.

Prehistoric Kerala's rainforests and wetlands, then thick with malaria-bearing mosquitoes and man-eating tigers, were largely avoided by Neolithic humans; indeed, no evidence of habitation prior to around 1,000 BCE exists. Only then did tribes of megalith-building proto-Tamil speakers from northwestern India settle Kerala. Subsequent contact with the Mauryan Empire spurred development of new Keralite polities, including the Cheran kingdom and feudal Namboothiri Brahminical city-states. More than a millennium of overseas contact and trade culminated in four centuries of struggle between and among multiple colonial powers and native Keralite states, a period whose end saw on January 11, 1956 the final formation of the modern-day state of Kerala.

Accounts of the etymology underlying "Kerala" differ; according to the prevailing theory, it as an imperfect portmanteau that fuses kera ("coconut palm tree") and alam ("land" or "location"). Natives of Kerala — "Keralites" — thus refer to their land as Keralam. Another theory has the name originating from the phrase chera alam ("land of the Chera").

Geography and climate

Further information: Geography of Kerala

Kerala’s 38,863 km² (1.18% of India’s landmass) are wedged between the Arabian Sea to the west and the Western Ghats — identified as one of the world's twenty-five biodiversity hotspots — to the east. Situated between north latitudes 8°18' and 12°48' and east longitudes 74°52' and 72°22', Kerala lies well within the humid tropics, near the equator. Kerala’s coast runs some 580 km in length, while the state itself varies between 35–120 km in width. Geographically, Kerala roughly divides into three climatically distinct regions. These include the eastern highlands (rugged and cool mountainous terrain), the central midlands (rolling hills), and the western lowlands (coastal plains). Located at the extreme southern tip of the Indian subcontinent, Kerala lies near the center of the Indian tectonic plate; as such most of the state (notwithstanding isolated regions) is subject to comparatively little seismic or volcanic activity. Geologically, pre-Cambrian and Pleistocene formations comprise the bulk of Kerala’s terrain. The topography consists of a hot and humid coastal plain gradually rising in elevation to the high hills and mountains of the Western Ghats. Kerala’s climate is mainly wet and maritime tropical, heavily influenced by the seasonal heavy rains brought by the Southwest Summer Monsoon.

| Agroecological zones of Kerala | |

| |

Eastern Kerala consists of rugged land enveloped by the rain shadow of the Western Ghats; the region thus includes high mountains, gorges, and deep-cut valleys. The wildest lands are covered with dense montane rainforests (an ecoregion of India), while other regions lie under tea and coffee plantations (established mainly in the 19th and 20th centuries) or other forms of cultivation. Forty-one of Kerala’s west-flowing rivers — as well as three of its east-flowing ones — originate in this region. Here, the Western Ghats form a wall of mountains interrupted near Palakkad; here, a natural mountain pass known as the Palakkad Gap breaks through to access rest of India. The Western Ghats rises on average to 1500 m elevation above sea level. Certain peaks may reach to 2500 m. Just west of the mountains lie the midland plains, comprising a swathe of land running along central Kerala. Here, rolling hills and shallow valleys fill a gentler landscape than that of the highlands. In the lowest lands, the midlands region hosts paddy fields; while, elevated land slopes play host to groves of rubber and fruit trees in addition to other crops such as black pepper, tapioca, and others. At lower elevations of between 250–1000 m, the forests of the Southwestern Ghats moist deciduous forest ecoregion range across the eastern portions of the Nilgiri and Palni Hills and include such formations as Agastyamalai and Anamalai.

Kerala’s western coastal belt is relatively flat. Part of the Malabar Coast moist forests ecoregion, much of it now consists of rice paddy fields, groves of coconut palms, and dense settlements. The area is crisscrossed by a network of interconnected canals and rivers known as the Kerala Backwaters region. The Backwaters are a particularly well-recognized feature of Kerala; it is an interconnected system of brackish water, with lakes and river-fed estuaries that lie just inland from the coast and runs virtually the entire length of the state. These highly facilitate inland travel throughout a region roughly bounded by Thiruvananthapuram in the south and Vadakara (which lies some 450 km to the north). Lake Vembanad — Kerala’s largest body of water — dominates the Backwaters; it lies between Alappuzha and Kochi and is over 200 km² in area. Indeed, around 8% of India's waterways (measured by length) are found in Kerala. The most important of Kerala’s forty-four rivers include the Periyar (244 km in length), the Bharathapuzha (209 km), the Pamba (176 km), the Chaliyar (169 km), the Kadalundipuzha (130 km), and the Achankovil (128 km). Most of the remainder are small and entirely fed by monsoon rains.

Kerala is mostly subject to the type of humid tropical wet climate experienced by most of Earth's rainforests. Whereas, its extreme eastern fringes experience a drier tropical wet and dry climate. Kerala receives an average annual rainfall of 3107 mm — some 70.3 km of water. This compares to the all-India average of 1,197 mm. Parts of Kerala's lowlands may average only 1250 mm annually while the cool mountainous eastern highlands of Idukki district — comprising Kerala's wettest region — receive in excess of 5,000 mm of orographic precipitation (4,200 mm of which are available for human use) annually. Kerala's rains are mostly the result of seasonal monsoons. As a result, Kerala averages some 120–140 rainy days per year. In summers, most of Kerala is prone to gale-force winds, storm surges, and torrential downpours accompanying dangerous cyclones coming in off the Indian Ocean. Kerala’s average maximum daily temperature is around 36.7 °C; the minumum is 19.8 °C.

Districts

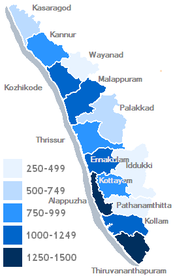

Fourteen districts comprise Kerala. The districts are distributed between Kerala's three historical regions: Malabar, Kochi, and Travancore. Malabar (northern Kerala) includes (from north to south) Kasargod, Kannur (Cannanore), Wayanad (Wynad), Kozhikode (Calicut), Malappuram, and Palakkad (Palghat). Kochi (central Kerala) includes Thrissur (Trichur) and Ernakulam (Cochin) districts. Lastly, the Travancore region (southern Kerala) is composed of Idukki, Alappuzha (Alleppey), Kottayam, Pathanamthitta, Kollam (Quilon), and Thiruvananthapuram (Trivandrum).

Mahe, a part of the union territory of Pondicherry, is an enclave within Kerala. Thiruvananthapuram is the state capital. Kochi is the largest city and considered the commercial capital of the state.

Flora and fauna

Most of Kerala, once largely covered in rainforests, is subject to a humid tropical climate; however, significant variations in terrain and elevation have resulted in a land whose biodiversity registers as among the world’s most significant. Most of the remaining undisturbed tracts of land lie in Kerala’s easternmost districts; coastal Kerala (along with portions of the east) mostly lies under cultivation and is home to comparatively little wildlife. Despite this, Kerala hosts two of the world’s Ramsar Convention-listed wetlands: Lake Sasthamkotta and the Vembanad-Kol wetlands are noted as being wetlands of international importance. There are also numerous protected conservation areas, including 1455.4 km² of the vast Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve.

Eastern Kerala’s windward mountains shelter tropical moist forests and tropical dry forests which are generally characteristic of the wider Western Ghats: crowns of giant sonokeling (binomial nomenclature: Dalbergia latifolia — Indian rosewood), anjili (Artocarpus hirsuta), mullumurikku (Erthrina), caussia, and other trees dominate the canopies of large tracts of virgin forest. These, in turn, play host to such major biota as Asian Elephant (Elephas maximus), Bengal Tiger (Panthera tigris tigris), Leopard (Panthera pardus), Indian Sloth Bear (Melursus (Ursus) ursinus ursinus), Gaur (the so-called "Indian Bison" — Bos gaurus), and Nilgiri Tahr (Nilgiritragus hylocrius). More remote preserves, including Silent Valley National Park in the Kundali Hills, harbor endangered species such as Lion-tailed Macaque (Macaca silenus) and Grizzled Giant Squirrel (Protoxerus stangeri). More common species include Porcupine, Chital (Axis axis), Sambar (Cervus unicolor), Gray Langur, Flying Squirrel, Swamp Lynx (Felis chaus kutas), Boar (Sus scrofa), a variety of catarrhine Old World monkey species, Gray Wolf (Canus lupus), Civet, and others.

Many reptiles, such as king cobra, viper, python, various turtles and crocodiles are to be found in Kerala — again, disproportionately in the east. Kerala's birds are numerous, including Peafowl, the Great Hornbill (Buceros bicornis) and Indian Grey Hornbill, Indian Cormorant, Jungle and Hill Myna, Oriental Darter, Black-hooded Oriole, Greater Racket-tailed and Black Drongoes, Bulbul (Pycnonotidae), species of Kingfisher and Woodpecker, Sri Lanka Frogmouth (Batrachostomus moniliger), Jungle Fowl, Alexandrine Parakeet, and assorted ducks and migratory birds.

History

Further information: History of KeralaKeralite legend recounts that Parasurama, an avatar of Mahavishnu, threw his battle axes into the sea as penance for his part in his sanguinary annihilation of the Kshatriya. As the axes sank beneath the waves, a new crescent-shaped land — bounded by what is now Gokarnam in the north and Kanyakumari in the south — rose from the waters. Kerala’s sobriquet — "God's own country" — derives from this legend. On the other hand, historians note the emergence of pre-historic pottery and granite burial monuments — which resembled their counterparts in Western Europe and the rest of Asia — by the 10th century BCE; these were built by speakers of a proto-Tamil language. Kerala’s first mention in written records is in the Sanskrit epic Aitareya Aranyaka. Later, figures such as Katyayana (4 century BCE) and Patanjali (2 century BCE) displayed in their writings a casual familiarity with Kerala's geography. Thus, ancient Roman philosopher Pliny the Elder in his Naturalis Historia (N.H. 6.26) mentions a certain Muziris (likely modern-day Kodungallur or Pattanam) as India's first port. Later, the unknown author of the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea notes that "both Muziris and Nelkunda (modern Kottayam) are now busy places". Malayalam, Kerala's native language, originated as an offshoot of Tamil, the native language of Tamil Nadu. Malayalam (Tamil: mala ("mountain") and alam ("location")) as a whole means the "living/inhabitants in mountain". This phrase, which in earlier times implied the geographical location of the region, was later replaced by Kerala. Thus, what is now Kerala was once simply another region inhabited mainly be Tamil-speakers; however, Kerala and Tamil Nadu diverged into linguistically separate regions by the early 14th century. The ancient Chera empire, whose court language was Tamil, ruled Kerala from their capital at Vanchi. Allied with the Pallavas, they continually warred against the neighbouring Chola and Pandya kingdoms. A Keralite identity, distinct from the Tamils and associated with the second Chera empire and the development of Malayalam, evolved during the 8th–14th centuries.

The Jewish settlers fleeing anti-Semitism brought Judaism to Kerala. Later, Arab merchants seeking spices and other goods brought Islam in the 8th century. Accounts of Christianity's arrival differ. According to one controversial theory (recounted by such sources as the Acts of Thomas and William Dalrymple), the Apostle Thomas landed at Kodungallur in 52 CE and founded Kerala's first Christian community. Meanwhile, other theories deny this by attributing Christianity's arrival to later dates. Afterwards, Jewish Christians settlers led by Knai Thoma ("Thomas of Cana"; alternatively, "Kana") arrived in 345 CE. With land and privileges granted by local Malabar Hindu ruler Cheraman Perumal, they founded Kerala’s Nasrani community. More than 1,100 years later, Vasco da Gama’s 1498-05-20 landing in Kozhikode (Calicut) inaugurated the arrival of Portuguese who sought to control the lucrative spice trade between the East Indies and Europe. They attempted — often via persecution — to convert Kerala’s Nasranis to Roman Catholicism. Da Gama established India's first Portuguese fortress at Cochin (Kochi) in 1503 and, taking advantage of rivalry between the royal families of Calicut and Cochin, ended the Arab monopoly. Conflicts between Calicut and Cochin, however, provided an opportunity for the Dutch to come in and finally expel the Roman Catholic Portuguese from their forts.

Ultimately, the Dutch were routed at the 1741 Battle of Kulachal by forces under Marthanda Varma of Thiruvithamcoore (Travancore). Meanwhile, Mysore’s Hyder Ali conquered northern Kerala, capturing Kozhikode in 1766. Ali’s successor, Tipu Sultan, launched in the late 18 century numerous campaigns against the growing British Raj, resulting in two of the four Anglo-Mysore wars. However, Tipu Sultan was ultimately forced to cede Malabar District and South Kanara, (including today’s Kasargod District) to the Raj in 1792 and 1799, respectively. The Raj then forged tributary alliances with Cochin (1791) and Travancore (1795). As a result, these became princely states under the Raj while maintaining local autonomy; meanwhile, Malabar and South Kanara districts were already part of the Raj’s Madras Presidency. In these colonial times, Kerala exhibited a relative paucity of mass defiance against the Raj — nevertheless, several rebellions occurred, led by figures such as Pazhassi Raja and Veluthampi Dalawa. A particularly potent threat to the British was the October 1946 Punnapra-Vayalar revolt. Yet most mass actions protested such social mores as untouchability. The non-violent Vaikom Satyagraham of 1924 was instrumental in securing entry to the public roads adjacent to the Vaikom temple for people belonging to backward castes. Finally, Maharaja Sree Chithira Thirunal Balaramavarma of Travancore issued the 1936 Temple Entry Proclamation. This declared his kingdom’s temples open to all Hindus, irrespective of caste.

After India gained independence in 1947, Travancore and Kochi were merged to form the province of Travancore-Cochin on July 1, 1949 — on 1950-01-26 (the date India became a republic), Travancore-Cochin was recognized as a state. In the same time, the Madras Presidency became Madras State in 1947. Finally, the Government of India's 1956-11-01 States Reorganisation Act inaugurated a new state — Kerala — incorporating Malabar District, Travancore-Cochin, and the taluk of Kasargod, South Kanara.A new Legislative Assembly was also created, for which elections were held in 1957. The elections resulted in a communist-led government — one of the world's first — headed by social activist and independence movement figure E.M.S. Namboodiripad. Subsequent radical reforms introduced by the Namboodiripad government favoured tenants and labourers — this facilitated, among other things, improvements in living standards, education, and life expectancies.

Politics

Kerala is governed via a parliamentary system of representative democracy with universal suffrage granted to residents. There are three branches of government. The legislature — the Legislative Assembly — is composed of elected members as well as special offices (the Speaker and Deputy Speaker) elected by assemblymen. In turn, Assembly meetings are presided over by the Speaker (or the Deputy Speaker, if the Speaker is absent). The judiciary is composed of an apex High Court of Kerala (including a Chief Justice combined with twenty-six permanent and two additional (pro tempore) justices) and a system of lower courts. Lastly, the executive authority — composed of the Governor of Kerala (the de jure head of state and appointed by the President of India), the Chief Minister of Kerala (the de facto head of state; the Legislative Assembly's majority party leader is appointed to this position by the Governor), and the Council of Ministers (appointed by the Governor, with input from the Chief Minister). In turn, the Council of Ministers answers to the Legislative Assembly.

Kerala hosts two major political alliances: the United Democratic Front (UDF — led by the Indian National Congress) and the Left Democratic Front (led by the — Communist Party of India (Marxist)). At present, the UDF is the ruling party and Oommen Chandy is the current Chief Minister. Nevertheless, Kerala numbers among India’s most left-wing states. Keralites themselves are comparatively very politically active in relation to most other Indian states.

Economy

Agriculture dominates the Keralite economy. Kerala lags behind many other Indian states and territories in terms of per capita GDP (11,819 INR) and economic productivity. However, Kerala's Human Development Index and standard of living statistics are the best in India. Indeed, in select development indices, Kerala rivals many developed countries. This seeming paradox — low GDP and productivity figures juxtaposed with relatively high development figures — is often dubbed the "Kerala Phenomenon" or the "Kerala Model" of development by economists, political scientists, and sociologists. This phenomenon arises mainly from Kerala's unusually strong service sector.

Kerala's economy can be best described as a democratic socialist welfare economy. However, Kerala's emphasis on equitable distribution of resources has resulted in slow economic progress compared to neighboring states (particularly Karnataka). Relatively few major corporations and manufacturing plants are headquartered in Kerala. Remittances from Keralites working abroad, mainly in the Middle East, make up over 20% of State Domestic Product (SDP).

Coconut, tea, coffee, rubber, cashew, and spices — including pepper, cardamom, vanilla, cinnamon, and nutmeg — comprise a critical agricultural sector. A key staple is rice, with some six hundred varieties grown in Kerala. Much of Kerala's agriculture is in the form of home gardens. The livestock sector plays a vital role in the economy of Kerala, and offers great potential for alleviating poverty and unemployment in rural areas. The majority of livestock owning farmers are small and/or marginal or even landless. In view of its suitability for combination with the crop sub-sector and its sustainability as a household enterprise with the active involvement of the farm women, livestock rearing is emerging as a very popular supplementary vocation in the small farm segment. Rural women play a significant role in the development of the livestock sub-sector and are involved in operations such as feeding, milking, breeding, management, health care and running micro-enterprises. It is estimated that about 32 lakh (3.2 million) out of the total number of 55 lakh (5.5 million) households in Kerala are engaged in livestock rearing for supplementing their income. The homestead settlement pattern, the relatively high level of literacy - particularly among women, the highly favourable agroclimatic conditions conducive for biomass production and the long tradition in livestock rearing are inherent strengths which the Kerala economy possesses in favour of livestock rearing. Government programs promote livestock use in Kerala via educational campaigns and the development of new cattle breeds such as the "Sunandini".

Kerala is an established tourist destination for both Indians and non-Indians alike. Tourists mostly visit such attractions as the beaches at Kovalam, Cherai and Varkala, the hill stations of Munnar, Nelliampathi, and Ponmudi, and national parks and wildlife sanctuaries such as Periyar and Eravikulam National Park. The "backwaters" region — an extensive network of interlocking rivers, lakes, and canals that center on Alleppey, Kumarakom, and Punnamada — also see heavy tourist traffic. Examples of Keralite architecture, such as the Padmanabhapuram Palace, Padmanabhapuram, are also visited. Kochi, the commercial capital of the state, is known as the "Queen of the Arabian Sea". Alappuzha, the first planned town in Kerala, is called the "Venice of the East". Tourism plays an important role in the state's economy.

Kerala has 145,704 km of roads (4.2% of India's total). This translates into about 4.62 km of road per thousand population, compared to an all-India average of 2.59 km. Virtually all of Kerala's villages are connected by road. Traffic in Kerala has been growing at a rate of 10–11% every year, resulting in high traffic and pressure on the roads. Total road length in Kerala increased by 5% between 2003-2004. The road density in Kerala is nearly four times the national average, and is a reflection of Kerala's unique settlement patterns. India's national highway network includes a Kerala-wide total of 1,524 km, which is only 2.6% of the national total. There are eight designated national highways in the state. Upgrading and maintenance of 1,600 km of state highways and major district roads have been taken up under the Kerala State Transport Project (KSTP), which includes the GIS-based Road Information and Management Project (RIMS).

Demographics

| Population density of Kerala | |

| |

| Source: (GOK 2001) harv error: no target: CITEREFGOK2001 (help). | |

Virtually all of Kerala's 3.18 crore (31.8 million) people are of Malayali ethnicity. Malayalis in turn number among southern India's Dravidian community, with traces of ancestry derived from various waves of Aryan invaders and settlers from northern India. Additional ancestries derive from several centuries of contact with non-Indian lands, whereby thousands of people of Arab, Jewish, Portuguese, Dutch, British, and other non-Dravidian ethnicities settled in Kerala. Many of these immigrants intermarried with native Malayalis. Nevertheless, Malayalam is Kerala's official language and is spoken by the vast majority of Keralites; the next most common language is Tamil, spoken mainly by Tamil laborers from Tamil Nadu. In addition, Kerala is home to 321,000 indigenous tribal Adivasis (1.10% of the populace). Some 63% of Adivasis reside in the eastern districts of Wayanad (where 35.82% are Adivasi), Palakkad (11.05%), and Idukki (15.66%). These groups, including the Irulars, Kurumbars, and Mudugars, speak their own native languages and experience hardships such as racial discrimination, economic exploitation, and poverty.

Kerala is home to 3.44% of India's people, and — at 819 persons per km² — its land is three times as densely settled as the rest of India. However, Kerala's negative population growth rate is far lower than the national average. Whereas Kerala's population more than doubled between 1951 and 1991 — adding 156 lakh (15.6 million) people to obtain an all-time peak of 291 lakh (29.1 million) residents — the population declined by 17 lakh (1.7 million) people between 1991 and 2001. Kerala's people are most densely settled in the coastal region, leaving the eastern hills and mountains comparatively sparsely populated

The major religions followed in Kerala are Hinduism (56.1%), Islam (24.7% — Keralite Muslims are known as Mappilas), and Christianity (19%). Kerala also had a tiny Jewish population until recently, said to date from 587 BC when they fled the occupation of Jerusalem by Nebuchadnezzar. The state has many famous temples, churches, and mosques. The synagogue in Kochi is the oldest in the Commonwealth of Nations. Importantly, Kerala has one of the most secular (non-sectarian) populations in India. Nevertheless, there have been signs of increasing disruptive influences from religious extremist organisations.

Kerala ranks highest in India with respect to social development indices such as elimination of poverty, primary education and healthcare. This resulted from significant efforts begun in 1911 by Cochin and Travancore states to boost healthcare and education among their ordinary people. This cental focus — unusual in India — was then maintained after Kerala's post-independence inauguration as a state. Thus, Kerala's literacy rate — 90.92% — and life expectancy are now the highest in India. However, the same is true of Kerala's unemployment and suicide rates. As per the 2001 census, Kerala is the only state in India with a female-to-male ratio higher than 0.99. The ratio for Kerala is 1.058 — 1058 females per 1000 males — while the national figure is 0.933. It is also the only state in India to have sub-replacement fertility. UNICEF and the World Health Organization (WHO) designated Kerala the world's first "baby-friendly state" via its "Baby Friendly Hospital" initiative. The state is also known for Ayurveda, a traditional system of medicine — this traditional expertise is currently drawing increasing numbers of medical tourists. However, drawbacks to this situation includes the population's steady aging — indeed, 11.2% of Keralites are age 60 or over.

Kerala's unusual socioeconomic and demographic situation was summarized by author and environmentalist Bill McKibben:

Kerala is a bizarre anomaly among developing nations, a place that offers real hope for the future of the Third World. Consider: This small state in India, though not much larger than Maryland, has a population as big as California's and a per capita annual income of less than $300. But its infant mortality rate is low, its literacy rate among the highest on Earth, and its birthrate below America's and falling faster. Kerala's citizens live nearly as long as Americans or Europeans. Though mostly a land of paddy-covered plains, statistically Kerala stands out as the Mount Everest of social development; there's truly no place like it.

Culture

See also: Music of KeralaKerala's culture — its civilization, artistic forms, beliefs, and worldview — are largely Dravidian in origin, although many distinctively Keralite traditions resulted from centuries of overseas contact. Native traditions of classical performing arts include koodiyattom, a form of Sanskrit drama or theatre and a UNESCO-designated Human Heritage Art. Kathakali (from katha ("story") and kali ("performance")) is a 500-year-old form of dance-drama that interprets ancient epics; a popularized offshoot of kathakali is Kerala natanam (developed in the 20th century by dancer Guru Gopinath). Meanwhile, koothu is a more light-hearted performance mode, akin to modern stand-up comedy; an ancient art originally confined to temple sanctuaries, it was later popularized by Mani Madhava Chakyar. Other Keralite performing arts include mohiniyaattam ("dance of the enchantress"), which is a type of graceful choreographed dance performed by women and accompanied by musical vocalizations. Thullal, padayani, and theyyam are other important Keralite arts. Kerala also has several tribal and folk art forms; also important are various performance genres that are Muslim- or Christian-themed. These include oppana, which is widely popular among Keralite Muslims and is native to Malabar. Oppana incorporates group dance accompanied by the beat of rhythmic hand clapping and ishal vocalizations.

However, many of these native art forms largely play to tourists or at youth festivals, and are not as popular among ordinary Keralites. Thus, more contemporary forms — including those heavily based on the use of often risqué and politically incorrect mimicry and parody — have gained considerable mass appeal in recent years. Indeed, contemporary artists often use such modes to mock socioeconomic elites. In recent decades, Malayalam cinema, yet another mode of widely popular artistic expression, have provided a distinct and indigenous Keralite alternative to both Bollywood and Hollywood.

The ragas and talas of lyrical and devotional carnatic music — another native product of South India — dominates Keralite classical musical genres. Swathi Thirunal Rama Varma, a 19th-century king of Travancore and an avid patron and composer of music, was instrumental in popularising carnatic music in early Kerala. Additionally, Kerala has its own native music system, sopanam, which is a lugubrious and step-by-step rendition of raga-based songs. It is sopanam, for example, that provides the background music used in kathakali. The wider traditional music of Kerala also includes melam (including the paandi and panchari variants), as style of percussive music performed at temple-centered festivals using an instrument known as the chenda. Up to 150 musicians may comprise the ensembles staging a given performance; each performance, in turn, may last up to four hours. Panchavadyam is a differing type of percussion ensemble consisting of five types of percussion instruments; these can be utilised by up to one hundred artists in certain major festivals. In addition to these, percussive music is also associated with various uniquely Keralite folk arts forms. Lastly, the popular music of Kerala — as in the rest of India — is dominated by the filmi music of Indian cinema.

Kerala also has an indigenous ancient solar calendar — the Malayalam calendar — which is used in various communities primarily for timing agricultural and religious activities. Kerala also has its own indigenous form of martial art — Kalarippayattu, derived from the words kalari ("place", "threshing floor", or "battlefield") and payattu ("exercise" or "practice"). Influenced by both Kerala’s Brahminical past and Ayurvedic medicine, kalaripayattu is attributed by oral tradition to Parasurama. After some two centuries of suppression by British colonial authorities, it is now experiencing strong comeback among Keralites while also steadily gaining worldwide attention. Other popular ritual arts include theyyam and poorakkali — these originate from northern Malabar, which is the northernmost part of Kerala.

See also

- List of famous Keralites

- List of Famous Politicians of Kerala

- Local Body Election in Kerala

- Pachakam

- Poorams

Notes

|

References

External links

|

|

| Districts of Kerala | ||

|---|---|---|

| State Districts | ||

| States and union territories of India | |

|---|---|

| States | |

| Union territories | |

Categories: