This is an old revision of this page, as edited by 84.71.49.216 (talk) at 17:37, 28 January 2006. The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 17:37, 28 January 2006 by 84.71.49.216 (talk)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)

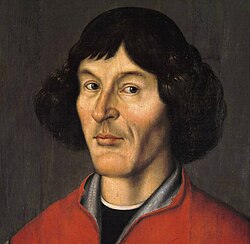

Nicolaus Copernicus (February 19, 1473 – May 24, 1543) was an astrologer, astronomer, mathematician, administrator and economist. His greatest legacy is the development of a scientifically-useful heliocentric (Sun-centered) theory of the solar system.

Copernicus worked in Royal Prussia as a church canon, governor, administrator, economist, jurist, physician, astrologer and, in conducting the defense against the Teutonic Order, as a military leader. Amid all his responsibilities, he treated astronomy as a hobby. However, his formulation of how the Sun rather than the Earth is at the center of the universe is considered one of the most important scientific hypotheses ever made, as it came to mark the starting point of modern astronomy and, in turn, modern science. It also encouraged young astronomers, scientists and scholars to take a more skeptical attitude toward established dogma.

Biography

Copernicus was born in 1473 at Toruń (Thorn) in a Polish province of Royal Prussia. His father Nikolas, a citizen of Cracow (Kraków), then capital of Poland, had moved to Toruń in 1460 once the war with the Teutonic Knights was concluded, and had become a respected citizen of that city. Copernicus was ten, when his father, a wealthy businessman and copper trader, died. Little is known of his mother, Barbara Watzenrode, who appears to have predeceased her husband. Copernicus' maternal uncle, Lucas Watzenrode, a church canon and later Prince-Bishop governor of Warmia, reared him and his three siblings after the death of Copernicus' father. Copernicus' had a brother and two sisters:

- Andreas became a canon at Frombork (Frauenburg)

- Barbara became a Benedictine nun

- Katharina married a businessman and city councillor, Barthel Gertner

In 1491 Copernicus enrolled at the Jagiellonian University in Cracow, and here for the first time encountered astronomy, thanks to his teacher Albert Brudzewski. This science soon fascinated him, as shown by his books (later carried off as war booty by the Swedes during "The Deluge", and now at the Uppsala University Library). After four years at Cracow, followed by a brief stay at Toruń, he went to Italy, where he studied law and medicine at the universities of Bologna and Padua. His bishop-uncle financed his education and wished for him to become a bishop as well. However, while studying canon and civil law at Ferrara, Copernicus met the famous astronomer, Domenico Maria Novara da Ferrara. Copernicus attended his lectures and became his disciple and assistant. The first observations that Copernicus made in 1497, together with Novara, are recorded in Copernicus' epochal book, De revolutionibus orbium coelestium.

In 1497 Copernicus' uncle was ordained Bishop of Warmia, and Copernicus was named a canon at Frombork (Frauenburg) Cathedral, but he waited in Italy for the great Jubilee of 1500. Copernicus went to Rome, where he observed a lunar eclipse and gave some lectures in astronomy or mathematics.

He would thus have visited Frombork only in 1501. As soon as he arrived, he requested and obtained permission to return to Italy to complete his studies at Padua (with Guarico and Fracastoro) and at Ferrara (with Giovanni Bianchini), where in 1503 he received his doctorate in canon law. It has been supposed that it was in Padua that he encountered passages from Cicero and Plato about opinions of the ancients on the movement of the Earth, and formed the first intuition of his own future theory. His collection of observations and ideas pertinent to his theory began in 1504.

Having left Italy at the end of his studies, he came to live and work at Frombork. Some time before his return to Warmia, he had received a position at the Collegiate Church of the Holy Cross in Wroclaw (Breslau), Silesia, which he would resign a few years before his death. Through the rest of his life he made astronomical observations and calculations, but always in his spare time and never as a profession.

Copernicus worked for years with the Prussian diet on monetary reform and published some studies about the value of money; as governor of Warmia, he administered taxes and dealt out justice. It was at this time (beginning in 1519, the year of Thomas Gresham's birth) that Copernicus came up with one of the earliest iterations of the theory now known as Gresham's Law. During these years he also traveled extensively on government business and as a diplomat, on behalf of the Prince-Bishop of Warmia.

In 1514 he made his Commentariolus — a short handwritten text describing his ideas about the heliocentric hypothesis — available to friends. Thereafter he continued gathering evidence for a more detailed work. During the war between the Teutonic Order and the Kingdom of Poland (1519–1524) Copernicus successfully defended Allenstein (Olsztyn) at the head of royal troops besieged by the forces of Albert of Brandenburg.

In 1533 Albert Widmannstadt delivered a series of lectures in Rome outlining Copernicus' theory. By 1536 Copernicus' work was already in definitive form, and some rumors about his theory had reached scientists all over Europe. From many parts of the continent, Copernicus received invitations to publish, but he feared persecution for his revolutionary work by the establishment. Cardinal Nicola Schönberg of Capua wrote, asking him to communicate his ideas more widely and requesting a copy for himself; "Therefore, learned man, without wishing to be inopportune, I beg you most emphatically to communicate your discovery to the learned world, and to send me as soon as possible your theories about the Universe, together with the tables and whatever else you have pertaining to the subject." Some have suggested that this note may have made Copernicus leery of publication, while others have suggested that the Church wanted to ensure that his ideas were published.