This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Callmederek (talk | contribs) at 13:11, 1 August 2010 (IP's edits were correct; "There ain't no such thing as a free lunch", is not an acronym; the redirect TANSTAAFL is what should be categorized. See Category:Acronyms). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 13:11, 1 August 2010 by Callmederek (talk | contribs) (IP's edits were correct; "There ain't no such thing as a free lunch", is not an acronym; the redirect TANSTAAFL is what should be categorized. See Category:Acronyms)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) This article is about the saying. For the computing principle, see No free lunch in search and optimization. For the group, see No Free Lunch (organization)."There ain't no such thing as a free lunch" (alternatively, "There's no such thing as a free lunch" or other variants) is a popular adage communicating the idea that it is impossible to get something for nothing. The acronyms TANSTAAFL and TINSTAAFL are also used. Uses of the phrase dating back to the 1930s and 1940s have been found, but the phrase's first appearance is unknown. The "free lunch" in the saying refers to the nineteenth century practice in American bars of offering a "free lunch" with drinks. The phrase and the acronym are central to Robert Heinlein's 1966 libertarian science fiction novel The Moon is a Harsh Mistress, which popularized it. The free-market economist Milton Friedman also popularized the phrase by using it as the title of a 1975 book, and it often appears in economics textbooks; Campbell McConnell writes that the idea is "at the core of economics".

History and usage

"Free lunch"

The "free lunch" referred to in the acronym relates back to the once-common tradition of saloons in the United States providing a "free" lunch to patrons who had purchased at least one drink. Rudyard Kipling, writing in 1891, noted how he came upon a barroom full of bad Salon pictures, in which men with hats on the backs of their heads were wolfing food from a counter.

“It was the institution of the "free lunch" I had struck. You paid for a drink and got as much as you wanted to eat. For something less than a rupee a day a man can feed himself sumptuously in San Francisco, even though he be a bankrupt. Remember this if ever you are stranded in these parts.″

TANSTAAFL, on the other hand, indicates an acknowledgment that in reality a person or a society cannot get "something for nothing". Even if something appears to be free, there is always a cost to the person or to society as a whole even though that cost may be hidden or distributed. For example, as Heinlein has one of his characters point out, a bar offering a free lunch will likely charge more for its drinks.

Early uses

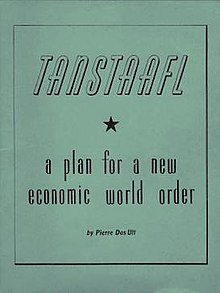

According to Robert Caro, Fiorello La Guardia, on becoming mayor of New York in 1934, said "È finita la cuccagna!", meaning "No more free lunch"; in this context "free lunch" refers to graft and corruption. The earliest known occurrence of the full phrase, in the form "There ain’t no such thing as free lunch", appears as the punchline of a joke related in an article in the El Paso Herald-Post of June 27, 1938, entitled "Economics in Eight Words". In 1945 "There ain't no such thing as a free lunch" appeared in the Columbia Law Review, and "there is no free lunch" appeared in a 1942 article in the Oelwein Daily Register (in a quote attributed to economist Harley L. Lutz) and in a 1947 column by economist Merryle S. Rukeyser. In 1949 the phrase appeared in an article by Walter Morrow in the San Francisco News (published on 1 June) and in Pierre Dos Utt's monograph, "TANSTAAFL: a plan for a new economic world order", which describes an oligarchic political system based on his conclusions from "no free lunch" principles.

The 1938 and 1949 sources use the phrase in relating a fable about a king (Nebuchadrezzar in Dos Utt's retelling) seeking advice from his economic advisors. Morrow's retelling, which claims to derive from an earlier editorial reported to be non-existent, but closely follows the story as related in the earlier article in the El Paso Herald-Post, differs from Dos Utt's in that the ruler asks for ever-simplified advice following their original "eighty-seven volumes of six hundred pages" as opposed to a simple failure to agree on "any major remedy". The last surviving economist advises that "There ain't no such thing as a free lunch".

In 1950, a New York Times columnist ascribed the phrase to economist (and Army General) Leonard P. Ayres of the Cleveland Trust Company. "It seems that shortly before the General's death ... a group of reporters approached the general with the request that perhaps he might give them one of several immutable economic truisms that he gathered from long years of economic study... 'It is an immutable economic fact,' said the general, 'that there is no such thing as a free lunch.'"

Meanings

| This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (May 2010) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

TANSTAAFL demonstrates opportunity cost. Greg Mankiw described the concept as: "To get one thing that we like, we usually have to give up another thing that we like. Making decisions requires trading off one goal against another." The idea that there is no free lunch at the societal level applies only when all resources are being used completely and appropriately, i.e., when economic efficiency prevails. If not, a 'free lunch' can be had through a more efficient utilisation of resources. If one individual or group gets something at no cost, somebody else ends up paying for it. If there appears to be no direct cost to any single individual, there is a social cost. Similarly, someone can benefit for "free" from an externality or from a public good, but someone has to pay the cost of producing these benefits.

In the sciences, TANSTAAFL means that the universe as a whole is ultimately a closed system—there is no magic source of matter, energy, light, or indeed lunch, that does not draw resources from something else, and will not eventually be exhausted. Therefore the TANSTAAFL argument may also be applied to natural physical processes in a closed system (either the universe as a whole, or any system that does not receive energy or matter from outside). (See Second law of thermodynamics.)

In mathematical finance, the term is also used as an informal synonym for the principle of no-arbitrage. This principle states that a combination of securities that has the same cash flows as another security must have the same net price in equilibrium.

TANSTAAFL is sometimes used as a response to claims of the virtues of free software. Supporters of free software often counter that the use of the term "free" in this context is primarily a reference to a lack of constraint ("libre") rather than a lack of cost ("gratis"). Richard Stallman has described it as "free as in speech not as in beer".

The prefix "TANSTAA-" is used in numerous other contexts as well to denote some immutable property of the system being discussed. For example, "TANSTAANFS" is used by Electrical Engineering professors to stand for "There Ain't No Such Thing As A Noise Free System".

See also

- No free lunch in search and optimization

- No-arbitrage bounds – mathematical relationships specifying simple limits on derivative prices

- Parable of the broken window – story by Frédéric Bastiat written to illuminate the notion of hidden costs

- science fiction fandom

- Tanstagi – There Ain't No Such Thing As Government Interference in the Schrödinger's Cat trilogy

- Tragedy of the commons

- Free rider problem

- Zero-sum game

References

- ^ Safire, William On Language; Words Left Out in the Cold" New York Times, 2-14-1993

- ^ Keyes, Ralph (2006). The Quote Verifier. New York: St. Martin's Press. p. 70. ISBN 978-0-312-34004-9.

- Smith, Chrysti M. (2006). Verbivore's Feast: Second Course. Helena, MT: Farcountry Press. p. 131. ISBN 978-1-56037-404-6.

- Gwartney, James D. (2005). Common Sense Economics. New York: St. Martin's Press. pp. 8–9. ISBN 0-312-33818-X.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - McConnell, Campbell R. (2005). Economics: principles, problems, and policies. Boston: McGraw-Hill Irwin. p. 3. ISBN 9780072819359. OCLC 314959936. Retrieved 2009-12-10.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Kipling, Rudyard (1930). American Notes. Standard Book Company. (published in book form in 1930, based on essays that appeared in periodicals in 1891)

- Heinlein, Robert A. (1997). The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress. New York: Tom Doherty Assocs. pp. 8–9. ISBN 0-312-86355-1.

- Shapiro, Fred (16 July 2009). "Quotes Uncovered: The Punchline, Please". The New York Times – Freakonomics blog. Retrieved 16 July 2009.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|work=(help) - Fred R. Shapiro, ed. (2006). The Yale Book of Quotations. New Haven, CT: Yale Univ. Press. p. 478. ISBN 978-0-300-10798-2.

- Dos Utt, Pierre (1949). TANSTAAFL: a plan for a new economic world order. Cairo Publications, Canton, OH.

- http://www.barrypopik.com/index.php/new_york_city/entry/no_more_free_lunch_fiorello_la_guardia/

- Fetridge, Robert H, "Along the Highways and Byways of Finance," The New York Times, Nov 12, 1950, p. 135

- Principles of Economics (4th edition), p. 4.

- Tucker, Bob, (Wilson Tucker) The Neo-Fan's Guide to Science Fiction Fandom (3rd-8th Editions), 8th edition: 1996, Kansas City Science Fiction & Fantasy Society, KaCSFFS Press, No ISSN or ISBN listed.