This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Nableezy (talk | contribs) at 19:58, 14 August 2010 (→Fatimid Caliphate: 973, not 972, reword slightly). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 19:58, 14 August 2010 by Nableezy (talk | contribs) (→Fatimid Caliphate: 973, not 972, reword slightly)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)| al-Azhar Mosque جامع الأزهر | |

|---|---|

Exterior view of al-Azhar Mosque. From left to right the minarets of al-Ghuri, Qaytbay, Aqbaghawiyya, and Katkhuda Exterior view of al-Azhar Mosque. From left to right the minarets of al-Ghuri, Qaytbay, Aqbaghawiyya, and Katkhuda | |

| Location | |

| Location | |

| Architecture | |

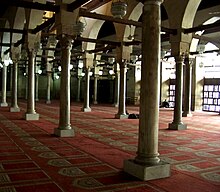

| Style | Hypostyle Mosque, Fatimid |

| Specifications | |

| Capacity | 20,000 |

| Minaret(s) | 4 |

Al-Azhar Mosque (Template:Lang-ar Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), "mosque of the most resplendent") is a mosque in Islamic Cairo in Egypt. Al-Mu‘izz li-Dīn Allāh of the Fatimid Caliphate commissioned its construction for the newly established capital city in 970. Its name is usually thought to allude to the Islamic prophet Muhammad's daughter Fatimah, a revered figure in Islam who was given the title az-Zahra (the shining one). It was the first mosque established in Cairo, a city that has since gained the nickname "the city of a thousand minarets."

After its dedication in 972, and with the hiring by mosque authorities of 35 scholars in 989, the mosque slowly developed into what is today the second oldest continuously run university in the world after Al Karaouine. Al-Azhar University has long been regarded as the foremost institution in the Islamic world for the study of Sunni theology and sharia, or Islamic law. The university, integrated within the mosque as part of a mosque-school since its inception, was nationalized and officially designated an independent university in 1961, following the Egyptian Revolution of 1952.

Over the course of its over a millennium long history, the mosque has been alternately neglected and highly regarded. Initially founded as an Ismāʿīli institution, Saladin and the Sunni Ayyubid dynasty that he founded shunned the institution, removing its status as a congregational mosque and denying stipends to students and teachers at its school. These moves were reversed under the Mamluk Sultanate, under whose rule numerous expansions and renovations took place. Later rulers of Egypt showed differing degrees of deference to the mosque, and provided widely varying levels of financial assistance, both to the school and to the upkeep of the mosque.

Given its history, al-Azhar remains a deeply influential institution in Egyptian society and a symbol of Islamic Egypt.

Name

The city of Cairo was established by Gawhar al-Ṣiqillī, the Fatimid general of Greek extraction from Sicily, who originally named it al-Mansuriyya (المنصوريه) after the prior seat of the Fatimid caliphate, al-Mansuriya in modern Tunisia. The mosque, first used in 971, may have initially been named Jāmi' al-Mansuriyya (جامع المنصوريه, "the mosque of Mansuriyya"), as was the common practice of the time. It was the Caliph al-Mu’izz li-Dīn Allāh who renamed the city al-Qāhira (القاهرة, "Cairo", meaning, "the Victorious"). The name of the mosque thus became Jāmi' al-Qāhira (جامع القاهرة, "the mosque of Cairo"), the first name of the mosque transcribed in Arabic sources.

The mosque acquired its current name, al-Azhar, sometime between the caliphate of al-Mu’izz and the end of the reign of the second Fatimid caliph in Egypt, al-Aziz Billah. Azhar is the masculine form for zahra, meaning "splendid" or "most resplendent." Zahra is an epithet applied to Fatimah, Muhammad's daughter by his first wife Khadija. Fatimah, the wife of caliph Alī ibn Abī Ṭālib, was claimed as the ancestress of al-Mu’izz li-Din Allāh and the imams of the Fatimid dynasty; the name of the mosque is generally thought to reference her.

Another theory for the choice of al-Azhar is that it is derived from the names the Fatimid caliphs had given to their palaces. The palaces near al-Azhar were given the name, collectively, of al-Qusur al-Zahira (االقصور الزاهرة, "the Brilliant Palaces") by al-Aziz Billah. The palaces had been completed and named prior to al-Azhar changing its name from Jāmi' al-Qāhira.

The word Jāmi' is derived from the Arabic root word jāmaʕa, meaning "to gather". The word is used for large congregational mosques. While in classical Arabic the name for al-Azhar remains Jāmi' al-Azhar, the pronunciation of the word Jāmi' changes to Gāma' in Egyptian Arabic.

History

Fatimid Caliphate

Caliph al-Mu’izz li-Din Allāh, the fourth Ismāʿīli Imam (through his general, Gawhar), conquered Egypt, wresting it from the Sunni Ikhshidid dynasty. By order of the Caliph, Gawhar then oversaw the construction of the royal enclosure of the Fatimid Caliphate and its army, and had al-Azhar built as a base to spread Ismāʿīli Shia Islam. Located near the densely populated Sunni city of Fustat, Cairo became the center of the Ismāʿīli sect of Shia Islam, and seat of the Fatimid empire.

Gawhar ordered the mosque's construction on April 4, 970, and it was quickly completed, in time for Friday prayers to first be held there on June 22, 971. Built to serve as the congregational mosque of Cairo, al-Azhar soon became a center of learning in the Islamic world. Official pronouncements and court sessions were issued from and convened there. Under Fatimid rule, the previously secretive teachings of the Ismāʿīli madh'hab ("school of law") were made available to the general public. Al-Nu‘man ibn Muhammad was appointed qadi under li-Din Allāh and placed in charge of the teaching of the Ismāʿīli madh'hab. Classes were taught at the palace of the Caliph, as well as at al-Azhar, with separate sessions available to women. During Eid ul-Fitr in 973, the mosque was rededicated by the caliph as the official congregational mosque in Cairo. Al-Mu’izz, and his son when he became Caliph, would perform at least one Friday khutbah during Ramadan at al-Azhar.

Fatimid efforts to establish Ismāʿīli practice among the population were largely unsuccessful, and al-Azhar became a Sunni institution shortly after the fall of that empire. In 988 CE, Ibn Killis, a polymath, jurist and the first official vizier of the Fatimids, made al-Azhar a key center for instruction in Islamic law. In 989, 45 scholars were hired to give lessons, laying the foundation for what would become the leading university in the Muslim world. Initially lacking a library, al-Azhar was endowed by the Fatimid caliph in 1005 with thousands of manuscripts that formed the basis of its collection. Much of that collection was dispersed in the chaos that ensued after the dynasty's collapse.

Ayyubid dynasty

Saladin, who overthrew the Fatimids in 1171, was hostile to the Shi’ite principles of learning propounded at al-Azhar during the Fatimid Caliphate, and under his Ayyubid dynasty the teaching center at the mosque suffered from neglect. Student funding was withdrawn and congregational prayers were banned by Sadr al-Din ibn Dirbass, appointed qadi by Saladin. This is attributed variously to Shāfi‘ī teachings that proscribe congregational prayers in a community to only one mosque, or to mistrust of the former Shia institution by the new Sunni ruler.

By this time, the much larger al-Hakim Mosque was completed; congregational prayers in Cairo were held there. Al-Azhar nevertheless remained the seat of Arabic philology throughout this period. While the Ayyubid dynasty neglected al-Azhar as a mosque and promoted the teaching of Sunni theology in subsidized madrasas built throughout Cairo, al-Azhar remained a place of learning, though it was denied financial assistance from the government. It eventually adopted Saladin's educational reforms modeled on the college system he instituted, and its fortunes improved under the Mamluks, who restored student stipends and salaries for the teaching staff (sheikhs).

Mamluk Sultanate

Congregational prayers were reestablished at al-Azhar during the Mamluk Sultanate by Sultan Baibars in 1266. Followers of the Hanafi madh'hab, no restriction on the number of congregational mosques applied. Al-Azhar had by now lost its association with the Fatimids and the Ismāʿīli doctrines, and with Cairo's rapid expansion, the need for mosque space allowed Baibars to disregard al-Azhar's history and restore the mosque to its former prominence. Under Baibars and the Mamluk Sultanate, al-Azhar saw the return of stipends for students and teachers, as well as the onset of work to repair the mosque, which had been neglected for nearly 100 years.

An earthquake in 1302 caused damage to al-Azhar and a number of other mosques throughout Mamluk territory. The responsibility for reconstruction was split among the amirs ("princes") of the Sultanate and the head of the army, Amir Salar, who was tasked with repairing the damage. These repairs were the first done since the reign of Baibars. Shortly after the earthquake two new madrasas were built along the exterior wall of the mosque to complement the space in al-Azhar, the Madrasa al-Aqbaghawiyya and the Madrasa al-Taybarsiyya. Both of the madrasas were built as complementary buildings to al-Azhar, with separate entrances and prayer halls.

Repairs and additional work were carried out by those in positions lower than sultan, though the mosque had regained its standing within Cairo under the Mamluks. This changed under the rule of al-Zahir Barquq, the first sultan of the Burji dynasty. The resumption of direct patronage by those in the highest positions of government continued through to the end of Mamluk rule. Improvements and additions were made by the sultans Qaytbay and Qansuh al-Ghuri, each of whom oversaw numerous repairs and erected minarets. As the preeminent learning center in the Islamic world, the sultans wished to have a noticeable association with al-Azhar. It was common practice among the Mamluk sultans to build minarets, perceived as symbols of power and the most effective way of cementing one's position in the Cairo cityscape.

Although the mosque-school was the leading university in the Islamic world and had regained royal patronage, it did not overtake the madrasas as the favored place of education among Cairo's elite. Al-Azhar maintained its reputation as an independent place of learning, whereas the madrasas that had first been constructed during Saladin's rule were fully integrated into the state educational system. Al-Azhar did continue to attract students from other areas in Egypt and the Middle East, far surpassing the numbers attending the madrasas. The student body was organized in riwaqs, or fraternities, along national lines, and the branches of Islamic law were studied. The average degree required six years of study.

By the 14th century, al-Azhar had achieved a preeminent place as the center for studies in law, theology, and Arabic, becoming a cynosure for students all around the Islamic world. However, among the ulema of Egypt, only one third were reported to have either attended or taught at al-Azhar. One account, by Muhammad ibn Iyas, reports that the Madrasa as-Salihiya, and not al-Azhar, was viewed as the "citadel of the ulema" at the end of the Mamluk Sultanate.

Province of the Ottoman Empire

With the Ottoman annexation of 1517, despite the mayhem their fight to control the city engendered, the Turks showed great deference to the mosque and its college, though direct royal patronage ceased. Sultan Selim I, the first Ottoman ruler of Egypt, attended al-Azhar for the congregational Friday prayer during his last week in Egypt, but did not donate anything to the upkeep of the mosque. Later Ottoman amirs likewise regularly attended Friday prayers at al-Azhar, but rarely provided subsidies for the maintenance of the mosque, though they did on occasion provide stipends for students and teachers. In contrast to the expansions and additions undertaken during the Mamluk Sultanate, only two Ottoman walīs ("governors") restored al-Azhar in the early Ottoman period.

Despite their defeat by Selim I and the Ottomans in 1517, the Mamluks remained an influential sector in Egyptian society, becoming beys, or chieftains, nominally under the control of the Ottoman governors, instead of amirs at the head of an empire. The first governor of Egypt under Selim I was Khai'r Bey, a Mamluk amir who had defected to the Ottomans during the Battle of Marj Dabiq. Even hough there were multiple revolts launched to reinstate the Mamluk Sultanate, including two in 1523, the Ottomans refrained from completely destroying the Mamluk hold over the power structure of Egypt. The Mamluks did suffer losses—both economic and military—in the immediate aftermath of the Ottoman victory, and this is reflected in the lack of financial assistance provided to al-Azhar in the first hundred years of Ottoman rule. By the 18th century the Mamluk elite had regained much of its influence and began to sponsor numerous renovations throughout Cairo and at al-Azhar specifically.

Al-Qazdughli, a powerful Mamluk bey, sponsored several additions and renovations in the early 18th century. Under his direction, a riwaq for blind students was added in 1735. He also sponsored the rebuilding of the Turkish and Syrian riwaqs, both of which had originally been built by Qaytbay.

This marked the beginning of the largest set of renovations to be undertaken since the expansions conducted under the Mamluk Sultanate. Abd al-Rahman Katkhuda was appointed katkhuda (head of the Janissaries) in 1749 and embarked on several projects throughout Cairo and at al-Azhar. Under his direction, three new gates were built: the Bab al-Muzayinīn, which eventually became the main entrance to the mosque; the Bab al-Sa'ayida; and, several years later, the Bab al-Shurba. A prayer hall was added to the south of the original one, doubling the size of the available prayer space. Katkhuda also refurbished or rebuilt several of the riwaqs that surrounded the mosque. Katkhuda was buried in a mausoleum he himself had built in Al-Azhar; in 1776, he became the first person (and the last) to be interred within the mosque since Nafissa al-Bakriyya, a female mystic who had died around 1588.

During the Ottoman period, al-Azhar regained its status as a favored institution of learning in Egypt, overtaking the madrasas that had been originally instituted by Saladin and greatly expanded by the Mamluks. By the end of the 18th century, al-Azhar had become inextricably linked to the ulema of Egypt, as compared to the end of the Mamluk Sultanate where only one-third either were educated or taught at al-Azhar. The ulema also were able to influence the government in an official capacity, with several sheikhs appointed to advisory councils that reported to the pasha, who in turn was appointed for only one year. This period also saw the introduction of more secular courses taught at al-Azhar, with science and logic joining philosophy in the curriculum.

Al-Azhar also served as a focal point for protests against the Ottoman occupation of Egypt, both from within the ulema and from among the general public. Student protests at al-Azhar were common and often shops in the vicinity of the mosque would close out of solidarity with the students. The ulema was also on occasion able to force its will over the government. In one instance, in 1730–31, Ottoman aghas harassed the residents living near al-Azhar while pursuing three fugitives. The gates at al-Azhar were closed in protest and the Ottoman governor, fearing a larger uprising, ordered the aghas to refrain from going near al-Azhar. Another disturbance occurred in 1791 in which the walī harassed the people near the al-Hussein Mosque, who then went to al-Azhar to demonstrate. The walī was subsequently dismissed from his post.

French occupation

Napoleon invaded Egypt in July 1798, arriving in Alexandria on July 2 and moving on to Cairo on July 22. In a bid to placate both the Egyptian population and the Ottoman Empire, Napoleon gave a speech in Alexandria in which he proclaimed his respect for Islam and the Sultan:

People of Egypt, you will be told that I have come to destroy your religion: do not believe it! Answer that I have come to restore your rights and punish the usurpers, and that, more than the Mamluks, I respect God, his Prophet and the Koran ... Is it not we who have been through the centuries the friends of the Sultan?

On July 25 Napoleon set up a diwan made up of nine al-Azhar sheikhs tasked with governing Cairo, the first body of Egyptians to hold official powers since the beginning of the Ottoman occupation. This practice of forming councils among the ulema of a city, first instituted in Alexandria, was put in place throughout French-occupied Egypt. Napoleon also unsuccessfully sought a fatwa from the al-Azhar imams that would deem it permissible under Islamic law to declare allegiance to Napoleon. His efforts to win over both the Egyptians and the Ottomans proved unsuccessful; the Ottoman Empire declared war on September 9, 1798 and an uprising from among the Egyptians took place the following month.

The revolt against French troops was launched from al-Azhar on October 21, 1798. Egyptians armed with stones, spears, and knives rioted and looted. The following morning the diwan met with Napoleon in an attempt to bring about a peaceful conclusion to the hostilities. Napoleon, initially incensed, agreed to attempt a peaceful resolution and asked the sheikhs of the diwan to organize talks with the rebels. The rebels, believing the move indicated weakness among the French, refused. Napoleon then ordered that the city be fired upon from the Cairo Citadel, aiming directly at al-Azhar. During the revolt two to three hundred French soldiers were killed, with 3,000 Egyptian casualties. Six of the ulema of al-Azhar were killed following summary judgments laid against them, with several more condemned. Any Egyptian caught by French troops was imprisoned or, if caught bearing weapons, beheaded. The French troops intentionally desecrated the mosque, walking in with their shoes on and guns displayed. The troops tied their horses to the mihrab and ransacked the student quarters and libraries, throwing copies of the Quran on the floor. The leaders of the revolt then attempted to negotiate a settlement with Napoleon, but were rebuffed.

Napoleon, who had been well-respected in Egypt and had earned himself the nickname Sultan el-Kebir (the Great Sultan) among the people of Cairo, lost their admiration and was no longer so addressed. In March 1800, French General Jean Baptiste Kléber was assassinated by Suleiman al-Halabi, a student at al-Azhar. Following the assassination, Napoleon ordered the closing of the mosque; the doors remained bolted until Ottoman and British assistance arrived in August 1801.

The conservative tradition of the mosque, with its lack of attention to science, was shaken by Napoleon's invasion. A seminal innovation occurred with the introduction of printing presses to Egypt, finally enabling the curriculum to shift from oral lectures and memorization to instruction by text, though the mosque itself only acquired its own printing press in 1930. Upon the withdrawal of the French, Muhammad Ali Pasha encouraged the establishment of secular learning, and history, math, and modern science were adopted into the curriculum. By 1872, under the direction of Jamāl al-Dīn al-Afghānī, European philosophy was also added to the study program.

Muhammad Ali Dynasty and British occupation

Following the French withdrawal, Muhammad Ali, the wāli and self-declared khedive of Egypt, sought to consolidate his newfound control of the country. To achieve this goal he made a series of moves designed to limit, and eventually subjugate, the ability of the al-Azhar ulema to influence the government. He imposed taxes on rizqa lands (tax-free property owned by mosques) and madrasas, from which al-Azhar drew a major portion of its income. In June 1809, he ordered that the deeds to all rizqa lands be forfeited to the state in a move that provoked outrage among the ulema. As a result, Umar Makram, the naqib al-ashraf, a prestigious Islamic post, led a revolt in July 1809. The revolt failed and Makram, an influential ally of the ulema, was exiled to Damietta.

Ali also sought to limit the influence of the al-Azhar sheikhs by allocating positions within the government to those educated outside of al-Azhar. He sent select students to France to be educated under a Western system and created an educational system based on that model that was parallel to, and thus bypassed, the system of al-Azhar.

Under the rule of Isma'il Pasha, the grandson of Muhammad Ali, major public works projects were initiated with the aim of transforming Cairo into a European styled city. These projects, at first funded by a boom in the cotton industry, eventually racked up a massive debt which was held by the British, providing an excuse for the British to occupy Egypt in 1882 after having pushed out Isma'il Pasha in 1879.

The reign of Isma'il Pasha also saw the return of royal patronage to al-Azhar. As khedive, Isma'il restored the Bab al-Sa'yida (first built by Katkhuda) and the Madrasa al-Aqbaghawiyya. Tewfik Pasha, Isma'il's son, who became khedive when his father was deposed as a result of British pressure, continued to restore the mosque. Tewfik renovated the prayer hall that was added by Katkhuda, also aligning the southeastern facade of the hall with the street behind it, and remodeling several other areas of the mosque. Abbas II succeeded his father Tewfik as khedive of Egypt and Sudan in 1892, and continued the renovations started by his grandfather Isma'il. He restructured the main facade of the mosque and built a new riwaq. Under his rule, the Committee for the Conservation of Monuments of Arab Art (initially formed under French occupation), also restored the original Fatimid sahn. These renovations were both needed and helped modernize al-Azhar and harmonize it with what was becoming a metropolis.

The major set of reforms that began under the rule of Isma'il Pasha continued under the British occupation. Muhammad Mahdi al-'Abbasi, sheikh al-Azhar, had instituted a set of reforms in 1872 intended to provide structure to the hiring practices of the university as well as to standardize the examinations taken by students. Further efforts to modernize the educational system were made under Hilmi's rule during the British occupation. The mosque's manuscripts were gathered into a centralized library, sanitation for students improved, and a regular system of exams instituted. From 1885, other colleges in Egypt were placed directly under the administration of the al-Azhar Mosque.

During Sa'ad Zaghloul's term as minister of education, before he went on to lead the Egyptian Revolution of 1919, further efforts were made to modify the educational policy of al-Azhar. While a bastion of conservatism in many regards, the mosque was opposed to Islamic fundamentalism, especially as espoused by the Muslim Brotherhood, founded in 1928. The school attracted students from throughout the world, including students from Southeast Asia and particularly Indonesia, providing a counterbalance to the influence of the Wahhabis in Saudi Arabia.

Under the reign of King Fuad I, two laws were passed that reorganized the educational structure at al-Azhar. The first of these, in 1930, split the school into three departments: Arabic language, sharia, and theology, with each department located in buildings outside of the mosque throughout Cairo. Additionally, formal examinations were required to earn a degree in one of these three fields of study. Six years later, a second law was passed that moved the main office for the school to a newly constructed building across the street from the mosque. Additional structures were later added to supplement the three departmental buildings.

The ideas advocated by several influential reformers in the early 1900s, such as Muhammad Abduh and Muhammad al-Ahmadi al-Zawahiri, began to take hold at al-Azhar in 1928, with the appointment of Mustafa al-Maraghi as rector. A follower of Abduh, the majority of the ulema opposed his appointment. Al-Maraghi and his successors began a series of modernizing reforms of the mosque and its school, expanding programs outside of the traditional subjects. Replaced after one year by al-Zawahiri, Maraghi would return to the post of rector in 1935, serving until his death in 1945. Al-Zawahiri, who had also been opposed by the ulema of the early 1900s, continued the efforts to modernize and reform al-Azhar. Following al-Maraghi's second term as rector, another student of Abduh was appointed rector.

Post-revolution

Following the Egyptian Revolution of 1952, led by the Free Officers Movement of Muhammad Naguib and Gamal Abdel Nasser, in which the Egyptian monarchy was overthrown, the university began to be separated from the mosque. A number of properties that surrounded the mosque were acquired and demolished to provide space for a modern campus by 1955. The mosque itself would no longer serve as a school, and the college was officially designated a university in 1961. The 1961 law separated the dual roles of the educational institution and the religious institution which made judgments heeded throughout the Muslim world. The law also created secular departments within al-Azhar, such as colleges of medicine, engineering, and economics, furthering the efforts at modernization first seen following the French occupation. The reforms of the curriculum have led to a massive growth in the number of Egyptian students attending al-Azhar run schools, specifically youths attending primary and secondary schools within the al-Azhar system. The number of students reported to attend al-Azhar primary and secondary schools has increased from under 90,000 in 1970 to 300,000 in the early in 1980s, up to nearly one million in the early 1990s, and exceeding 1.3 million students in 2001.

During his tenure as Prime Minister, and later President, Nasser continued the efforts to limit the power of the ulema of al-Azhar and to use its influence to his advantage. He abolished the sharia courts, merging religious courts with the state judicial system in 1955, severely limiting the independence of the ulema. He also ordered that all mosques be placed under the newly created Ministry of Religious Endowments, cutting off the ability of the mosque to control its financial affairs. The 1961 reform law, which invalidated an earlier law passed in 1936 that had guaranteed the independence of al-Azhar, gave the President of Egypt the authority to appoint the sheikh al-Azhar, a position first created during Ottoman rule and chosen from and by the ulema since its inception. Al-Azhar, which remained a symbol of the Islamic character of both the nation and the state, continued to influence the population while being unable to exert its will over the state. Al-Azhar became increasingly co-opted into the state bureaucracy after the revolution—independence of its curriculum and its function as a mosque ceased. The authority of the ulema were further weakened by the creation of government agencies responsible for providing interpretations of religious laws.

Al-Azhar, now fully integrated as an arm of the government, was then used to justify actions of the government. Although the ulema had in the past issued rulings that socialism is irreconcilable with Islam, following the Revolution's land reforms new rulings were supplied giving Nasser a religious justification for what he termed an "Islamic" socialism. The ulema would also serve as a counterweight to the Muslim Brotherhood, and to Saudi Arabia's Wahhabi influence. An assassination attempt on Nasser was blamed on the Brotherhood, and the organization was outlawed. Nasser, needing support from the ulema as he initiated mass arrests of Brotherhood members, relaxed some of the restrictions placed on al-Azhar. The ulema of al-Azhar in turn consistently supported him in his attempts to dismantle the Brotherhood, and continued to do so in subsequent regimes. Despite the efforts of Nasser and al-Azhar to discredit the Brotherhood, the organization continued to function. Al-Azhar also provided legitimacy for war with Israel in 1967, declaring the conflict against Israel a "holy struggle."

Following Nasser's death in 1970, Anwar Sadat became President of Egypt. Sadat wished to restore al-Azhar as a symbol of Egyptian leadership throughout the Arab world, saying that "the Arab world cannot function without Egypt and its Azhar." Recognizing the growing influence of the Muslim Brotherhood, Sadat relaxed several restrictions on the Brotherhood and the ulema as a whole. However, in an abrupt about-face, in September 1971 a crackdown was launched on journalists and organizations that Sadat felt were undermining or attacking his positions. As part of this effort to silence criticism of his policies, Sadat instituted sanctions against any of the ulema who criticized or contradicted official state policies. The ulema of al-Azhar continued to be used as a tool of the government, sparking criticism among several groups, including Islamist and other more moderate groups. Shukri Mustafa, an influential Islamist figure, accused the ulema of providing religious judgments for the sole purpose of government convenience. When Sadat needed support for making peace with Israel, which the vast majority of the Egyptian population regarded as an enemy, al-Azhar provided a decree stating that the time had come to make peace.

Al-Azhar continues to hold a status above other Sunni religious authorities throughout the world, and as Sunnis form a large majority of the total Muslim population al-Azhar exerts considerable influence on the Islamic world as a whole. In addition to being the default authority within Egypt, al-Azhar has been looked to outside of Egypt for religious judgments. Prior to the Gulf War, Saudi Arabia's King Fahd asked for a fatwa authorizing the stationing of foreign troops within the kingdom, and despite Islam's two holiest sites being located within Saudi Arabia, he asked the head sheikh of al-Azhar instead of the grand mufti of Saudi Arabia. In 2003, Nicolas Sarkozy, at the time French Minister of the Interior, requested a judgment from al-Azhar allowing Muslim girls to not wear the hijab in French public schools, despite the existence of the French Council of Islam. The sheikh of al-Azhar provided the ruling, saying that while wearing the hijab is an "Islamic duty" the Muslim women of France are obligated to respect and follow French laws. The ruling drew much criticism within Egypt as compromising Islamic principles to convenience the French government, and in turn the Egyptian government.

Architecture

The architecture of al-Azhar is closely tied to the history of Cairo. Materials taken from multiple periods of Egyptian history, from the Ancient Egyptians, through Greek and Roman rule, to the Coptic Christian era, were used in the early mosque structure, which drew on other Fatimid structures in Ifriqiya. Later additions from the different rulers of Egypt likewise show influences from both within and outside of Egypt. Sections of the mosque show many of these influences blended together while others show a single inspiration, such as domes from the Ottoman period and minarets built by the Mamluks.

Initially built as a prayer hall with five aisles and a modest central courtyard, the mosque has since been expanded multiple times with additional installations completely surrounding the original structure. Many of Egypt's rulers have shaped the art and architecture of al-Azhar, from the minarets added by the Mamluks and the gates added during Ottoman rule to more recent renovations such as the installation of a new mihrab. None of the original minarets or domes have survived, with some of the current minarets having been rebuilt several times.

Current layout and structure

The present main entrance to the mosque is the Bab al-Muzayinīn, which opens into the white marble-paved courtyard at the opposite end of the main prayer hall. To the northeast of the Bab al-Muzayinīn, the courtyard is flanked by the façade of the Madrasa al-Aqbaghawiyya; the southwestern end of the courtyard leads to the Madrasa al-Taybarsiyya. Directly across the courtyard from the entrance to the Bab al-Muzayinīn is the Bab al-Gindi (Gate of Qaytbay), built in 1495, above which stands the minaret of Qaytbay. Through this gate lies the courtyard of the prayer hall.

The mihrab has recently been changed to a plain marble facing with gold patterns.

Structural evolution under Fatimids

Completely surrounded by dependencies added as the mosque was used over time, the original structure was Template:Ft to m in length and Template:Ft to m wide, and comprised three arcades situated around a courtyard. To the southeast of the courtyard, the original prayer hall was built as a hypostyle hall, five aisles deep. Measuring Template:Ft to m by Template:Ft to m, the qibla wall was slightly off the correct angle. The marble columns supporting the four arcades that made up the prayer hall were reused from sites extant at different times in Egyptian history, from Pharaonic times through Roman rule to Coptic dominance. The different heights of the columns were made level by using bases of varying thickness. The stucco exterior shows influences from Abbasid, Coptic and Byzantine architecture.

Ultimately a total of three domes were built, a common trait among early north African mosques, although none of them have survived Al-Azhar's many renovations. The historian al-Maqrizi recorded that in the original dome al-Siqilli inscribed the following:

In the name of Allah, the Merciful, the Compassionate; according to the command for its building from the servant of Allah, His governor abu Tamim Ma'ad, the Imam al-Mu‘izz li-Dīn Allāh, Amir al-Mu'minin, for whom and his illustrious forefathers and his sons may there be the blessings of Allah: By the hand of his servant Jawhar, the Secretary, the Ṣiqillī in the year 360.

Gawhar included the honorific Amir al-Mu'minin, Commander of the Faithful, as the Caliphs title and also included his nickname "the Secretary" which he had earned serving as a secretary prior to becoming a general.

The original mihrab, uncovered in 1933, has a semi-dome above it with a marble column on either side. Intricate stucco decorations were a prominent feature of the mosque, with the mihrab and the walls ornately decorated. The mihrab had two sets of verses from the Quran inscribed in the conch, which is still intact. The first set of verses are the three that open al-Mu’minoon:

قَدْ أَفْلَحَ الْمُؤْمِنُونَ – الَّذِينَ هُمْ فِي صَلَاتِهِمْ خَاشِعُونَ – وَالَّذِينَ هُمْ عَنِ اللَّغْوِ مُعْرِضُونَSuccessful indeed are the believers – who are humble in their prayers – and who avoid vain talk

The next inscription is made up of verses 162 and 163 of al-An'am:

قُلْ إِنَّ صَلَاتِي وَنُسُكِي وَمَحْيَايَ وَمَمَاتِي لِلَّهِ رَبِّ الْعَالَمِينَ – لَا شَرِيكَ لَهُ وَبِذَلِكَ أُمِرْتُ وَأَنَا أَوَّلُ الْمُسْلِمِينَSay: Surely my prayer and my sacrifice and my life and my death are (all) for Allah, the Lord of the worlds – No associate has He; and this am I commanded, and I am the first of those who submit.

These inscriptions are the only surviving piece of decoration that has been definitively traced to the Fatimids.

The marble paved central courtyard was added between 1009 and 1010. The arcades that surround the courtyard have keel shaped arches with stucco inscriptions. The arches were built during the reign of al-Hafiz li-Din Allah. The stucco ornaments also date to his rule and were redone in 1891. Two types of ornaments are used. The first appears above the center of the arch and consists of a sunken roundel and twenty-four lobes. A circular band of vegetal motifs was added in 1893. The second ornament used, which alternates with the first appearing in between each arch, consists of shallow niches below a fluted hood. The hood rests on engaged columns which are surrounded by band of Qu'ranic writing in Kufic script. The Qu'ranic script was added after the rule of al-Hafiz but during the Fatimid period. The walls are topped by a star shaped band with tiered triangular crenellations. The southeastern arcade of the courtyard contains the main entrance to the prayer hall. A Persian framing gate, in which the central arch of the arcade is further in with a higher rectangular pattern above it, opens into the prayer hall.

A new wooden door was installed by al-Hakim in 1009; in 1125 al-Amir installed a new wooden mihrab. Al-Hafiz li-Din Allah added a fourth arcade around the courtyard, as well as an additional dome.

Mamluk additions

The Fatimid dynasty was succeeded by the rule of Saladin and his Ayyubid dynasty. Initially appointed vizier by the last Fatimid Caliph Al-'Āḍid (who incorrectly thought he could be easily manipulated), Saladin consolidated power in Egypt, allying that country with the Sunni Abbasid Caliphate in Baghdad. Distrusting al-Azhar for its Shia history, the mosque lost prestige during his rule. However, the succeeding Mamluk dynasty made restorations and additions to the mosque, overseeing a rapid expansion of its educational programs. Among the restorations was a modification of the mihrab, with the installation of a polychrome marble facing.

The Madrasa al-Taybarsiyya, which contains the tomb of Amir Taybars, was built in 1309. Originally intended to function as a complementary mosque to al-Azhar it has since been integrated with the rest of the mosque. The Maliki and Shāfi‘ī madh'hab were studied in this madrasa, though it now is used to hold manuscripts from the library. The only surviving piece from the original is the qibla wall and its polychrome mihrab.

A dome and minaret cover the Madrasa al-Aqbaghawiyya, which contains the tomb of Amir Aqbugha, which was built in 1339. Intended by its founder, Aqbugha 'Abd al-Wahid, to be a stand-alone mosque and school, the madrasa has since become integrated with the rest of the mosque. The entrance, qibla wall, and glass mosaic in the mihrab are all original with the dome dating to the Ottoman period.

Built in 1440, the Madrasa Gawhariyya contains the tomb of Gawhar al-Qanaqba'i, a Sudanese eunuch who became treasurer to the sultan. The floor of the madrasa is marble, the walls lined with cupboards, decoratively inlaid with ebony, ivory, and nacre. The tomb chamber is covered by small arabesque dome.

Minaret of Qaytbay

Built in 1483 with two octagonal and one cylindrical shafts, the Minaret of Qaytbay also has three balconies, supported by muqarnas, a form of stalactite vaulting which provide a smooth transition from a flat surface to a curved one (first recorded to have been used in Egypt in 1085), that adorn the minaret. The first shaft is octagonal is decorated with keel-arched panels on each side, with a cluster of three columns separating each panel. Above this shaft is the second octagonal shaft which is separated from the first by a balcony and decorated with plaiting. A second balcony separates this shaft with the final cylindrical shaft, decorated with four arches. Above this is the third balcony, crowned by the finial top of the minaret.

The minaret is believed to have been built in the area of an earlier, Fatimid-era brick minaret that had itself been rebuilt several times. Contemporary accounts suggest that the Fatimid minaret had defects in its construction and needed to be rebuilt several times, including once under the direction of Sadr al-Din al-Adhra'i al-Dimashqi al-Hanafi, the qadi al-qudat (Chief Justice of the Highest Court) during the rule of Sultan Baibars. Recorded to have been rebuilt again under Barquq in 1397, the minaret began to lean at a dangerous angle and was rebuilt in 1414 by Taj al-Din al-Shawbaki, the walī and muhtasib of Cairo, and again in 1432. The Qaytbay minaret was built in its place as part of a reconstruction of the entrance to the mosque.

Bab al-Gindi

Directly across the courtyard from the entrance from the Bab al-Muzayinīn is the Bab al-Gindi (Gate of Qaytbay). Built in 1495, this gate leads to the court of the prayer hall.

Ghuri minaret

The double finial minaret was built in 1509 by Qansah al-Ghuri. Sitting on a square base, the first shaft is octagonal, and four sides have a decorative keel arch, separated from the adjacent sides with two columns. The second shaft, separated from the first by a fretted balconies supported by muqarnas, is also octagonal and decorated with blue faience. A balcony separates the third level from the second shaft. The third level is made up of two rectangular shafts with horseshoe arches on each side of both shafts. Atop each of these two shafts rests a finial, with a balcony separating the finials from the shafts.

Ottoman renovations and additions

Several additions and restorations were made during Ottoman reign in Egypt, many of which were completed under the direction of Abd al-Rahman Katkhuda who nearly doubled the size of the mosque. Three gates were added by Katkhuda, the Bab al-Muzayinīn (Gate of the Barbers), which became the main entrance to the mosque, the Bab al-Shurba (the Soup Gate), from which food, often rice soup, would be served to the students, and the Bab al-Sa'ayida (Gate of the Sa'idis), named for the people of Upper Egypt. Several riwaqs were added, including one for the blind students of al-Azhar, as well as refurbished during the Ottoman period. Katkhuda also added an additional prayer hall south of the original Fatimid hall, with an additional mihrab, doubling the total prayer area.

Bab al-Muzayinīn

The Bab al-Muzayinīn (باب المزينين, "Gate of the Barbers"), so named because students would have their heads shaved outside of the gate, was built in 1753. Credited to Katkhuda the gate has two doors, each surrounded by recessed arches. Two moulded semi-circular arches with tumpanums decorated with trefoils above the doors. Above the arches is a frieze with panels of cypress trees, a common trait of Ottoman work.

A free-standing minaret, built by Katkhuda, originally stood outside the gate. The minaret was demolished prior to the opening of al-Azhar street by Tewfik Pasha during modernization efforts which took place throughout Cairo.

See also

Endnotes

^ i The Mosque of Amr ibn al-As is the oldest mosque in modern Cairo (as well as the oldest mosque in Africa), built in 642 CE. However, the Mosque of Amr ibn al-As, as well as several others in modern Cairo that are older than al-Azhar, was built in the city of Fustat. Cairo has expanded and now includes Fustat within its borders.

^ ii One of the main identifying characteristics of Egyptian Arabic is the hard g in place of j in the pronunciation of the letter ǧīm. This modification dates to some time between the 19th and 20th centuries. See Izre'el & Raz 1996, p. 153.

Footnotes

- ^ Rabbat 1996, p. 53

- ^ Bennison & Gascoigne 2007, p. 104

- Tracy 2000, p. 507

- Hitti 1973, p. 114

- ^ Summerfield, Devine & Levi 1998, p. 9

- Williams 2002, p. 151

- ^ Petry & Daly 1998, p. 139

- ^ Yeomans 2006, p. 52

- ^ Yeomans 2006, p. 53

- Daftary 1998, p. 96

- Dodge 1961, pp. 6–7

- Daftary 1998, p. 95

- ^ Behrens-Abouseif 1992, p. 58

- ^ Summerfield, Devine & Levi 1998, p. 10

- ^ Rabbat 1996, p. 56

- ^ Behrens-Abouseif 1992, p. 60

- Lulat 2005, p. 77

- ^ Rabbat 1996, p. 57

- ^ Rabbat 1996, p. 58

- ^ Rabbat 1996, p. 59

- ^ Winter 2004, p. 115

- Winter 2004, p. 12

- Winter 2004, p. 14

- Rabbat 1996, pp. 59–60

- ^ Rabbat 1996, pp. 49–50

- ^ Rabbat 1996, pp. 60–61

- Abu Zayd, Amirpur & Setiawan 2006, p. 36

- Rahman 1984, p. 36

- Winter 2004, p. 120

- Winter 2004, p. 121

- ^ Raymond 2000, p. 293

- ^ Watson 2003, pp. 13–14

- ^ Rabbat 1996, p. 61

- Dwyer 2008, p. 380

- Watson 2003, p. 14

- ^ McGregor 2006, p. 43

- Flower 1976, p. 49

- Dwyer 2008, p. 403

- ^ Dwyer 2008, p. 404

- Richmond 1977, p. 25

- Asprey 2000, p. 293

- Flower 1976, p. 27

- ^ Summerfield, Devine & Levi 1998, p. 11

- Petry & Daly 1998, p. 148

- ^ Raymond 2000, p. 312

- Shillington 2005, p. 199

- ^ Rabbat 1996, p. 62

- ^ Summerfield, Devine & Levi 1998, p. 12

- ^ Rabbat 1996, p. 63

- Abu Zayd, Amirpur & Setiawan 2006, p. 19

- ^ Rahman 1984, p. 64

- ^ Voll 1994, p. 183

- Goldschmidt 2000, p. 123

- ^ Summerfield, Devine & Levi 1998, p. 13

- Abdo 2002, pp. 50–51

- Zaman 2002, p. 60

- Harrison & Berger 2006, p. 173

- Zaman 2002, p. 86

- Hefner & Zaman 2007, p. 110

- Abdo 2002, pp. 49–50

- Choueiri 2005, p. 79

- Lulat 2005, p. 79

- Binder 1988, p. 340

- ^ Abdo 2002, p. 51

- Abdo 2002, p. 52

- Aburish 2004, p. 200

- Shillington 2005, p. 478

- Aburish 2004, p. 88

- ^ Abdo 2002, p. 31

- ^ Abdo 2002, p. 54

- Rahman 1984, p. 31

- Harrison & Berger 2006, p. 165

- Hefner & Zaman 2007, p. 123

- ^ Rabbat 1996, p. 50

- Rabbat 1996, p. 45

- ^ Rabbat 1996, p. 46

- ^ Rabbat 1996, pp. 47–48

- ^ Rabbat 1996, p. 51

- Beattie 2005, p. 103

- Dodge 1961, p. 5

- Holt, Lambton & Lewis 1977, p. 713

- Rivoira & Rushforth 1918, p. 154

- ^ Behrens-Abouseif 1992, p. 59

- Petersen 2002, p. 45

- Dodge 1961, pp. 3–4

- ^ Rabbat 1996, p. 64

- Abdo 2002, p. 45

- ^ Rabbat 1996, p. 47

- Shillington 2005, p. 438

- Petry & Daly 1998, p. 312

- ^ Yeomans 2006, p. 56

- ^ Holt, Lambton & Lewis 1977, p. 731

- ^ Yeomans 2006, p. 55

- Petersen 2002, p. 208

- Bloom 1988, p. 21

- ^ Yeomans 2006, p. 54

- Russell 1962, p. 185

- Gottheil 1907, p. 503

References

- Abdo, Geneive (2002), No God But God: Egypt and the Triumph of Islam, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-515793-2

- Abu Zayd, Nasr Hamid; Amirpur, Katajun; Setiawan, Mohamad Nur Kholis (2006), Reformation of Islamic thought: a critical historical analysis, Amsterdam University Press, ISBN 978-90-5356-828-6

- Aburish, Said K. (2004), Nasser, the Last Arab, St. Martin's Press, ISBN 978-0-312-28683-5

- Asprey, Robert B. (2000), The rise of Napoleon Bonaparte, Basic Books, ISBN 978-0-465-04881-6

- Beattie, Andrew (2005), Cairo: a cultural history, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-517893-7

- Behrens-Abouseif, Doris (1992), Islamic Architecture in Cairo (2nd ed.), Brill, ISBN 978-90-04-09626-4

- Bennison, Amira K.; Gascoigne, Alison L., eds. (2007), Cities in the pre-modern Islamic world, Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-42439-4

- Binder, Leonard (1988), Islamic liberalism: a critique of development ideologies, University of Chicago Press, ISBN 978-0-226-05147-5

- Bloom, Jonathan (1988), "The Introduction of the Muqarnas into Egypt", in Grabar, Oleg (ed.), Muqarnas: An Annual on Islamic Art and Architecture, vol. 5, Brill, pp. 21–28, ISBN 978-90-04-08647-0

- Choueiri, Youssef, ed. (2005), A companion to the history of the Middle East, Wiley-Blackwell, ISBN 978-1-4051-0681-8

- Creswell, K. A. C. (1952), The Muslim Architecture of Egypt I, Ikhshids and Fatimids, A.D. 939–1171, Oxford University Press

- Creswell, K. A. C. (1959), The Muslim Architecture of Egypt II, Ayyubids and Early Bahrite Mamluks, A.D. 1171–1326, Oxford University Press

- Daftary, Farhad (1998), A short history of the Ismailis: traditions of a Muslim community, Edinburgh University Press, ISBN 978-1-55876-194-0

- Dodge, Bayard (1961), Al-Azhar: A Millennium of Muslim learning, Middle East Institute

- Dwyer, Philip G. (2008), Napoleon: the path to power, Yale University Press, ISBN 978-0-300-13754-5

- Flower, Raymond (1976), Napoleon to Nasser: the story of modern Egypt, Taylor & Francis, ISBN 978-0-905562-00-1

- Goldschmidt, Arthur (2000), Biographical dictionary of modern Egypt, Lynne Rienner Publishers, ISBN 978-1-55587-229-8

- Gottheil, Richard (1907), "Al-Azhar The Brilliant: The Spiritual Home of Islam", The Bookman, Dodd, Mead and Company

- Harrison, Lawrence E.; Berger, Peter, eds. (2006), Developing cultures: case studies, CRC Press, ISBN 978-0-415-95280-4

- Hefner, Robert W.; Zaman, Muhammad Qasim, eds. (2007), Schooling Islam: the culture and politics of modern Muslim education, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-12933-4

- Hitti, Philip Khuri (1973), Capital cities of Arab Islam, University of Minnesota Press, ISBN 978-0-8166-0663-4

- Holt, Peter Malcolm; Lambton, Ann; Lewis, Bernard, eds. (1977), The Cambridge History of Islam, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-29138-5

- Izre'el, Shlomo; Raz, Shlomo (1996), Studies in modern Semitic languages, Brill, ISBN 978-90-04-10646-8

- Lulat, Y. G-M. (2005), A history of African higher education from antiquity to the present: a critical synthesis, Praeger Publishers, ISBN 978-0-313-32061-3

- McGregor, Andrew James (2006), A military history of modern Egypt: from the Ottoman Conquest to the Ramadan War, Greenwood Publishing Group, ISBN 978-0-275-98601-8

- Petersen, Andrew (2002), Dictionary of Islamic Architecture, Routledge, ISBN 978-0-203-20387-3

- Petry, Carl F.; Daly, M. W., eds. (1998), The Cambridge history of Egypt, vol. 1, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-47137-4

- Rabbat, Nasser (1996), "Al-Azhar Mosque: An Architectural Chronicle of Cairo's History", in Necipogulu, Gulru (ed.), Muqarnas- An Annual on the Visual Culture of the Islamic World, vol. 13, Brill, pp. 45–67, ISBN 978-90-04-10633-8

- Rahman, Fazlur (1984), Islam & modernity: transformation of an intellectual tradition, University of Chicago Press, ISBN 978-0-226-70284-1

- Raymond, André (2000), Cairo, Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0-674-00316-3

- Richmond, John C. B. (1977), Egypt, 1798–1952: her advance towards a modern identity, Taylor & Francis, ISBN 978-0-416-85660-6

- Rivoira, Giovanni Teresio; Rushforth, Gordon McNeil (1918), Moslem architecture, Oxford University Press

- Russell, Dorothea (1962), Medieval Cairo and the Monasteries of the Wādi Natrūn, Weidenfeld & Nicolson

- Shillington, Kevin, ed. (2005), Encyclopedia of African history, CRC Press, ISBN 978-1-57958-453-5

- Siddiqi, Muhammad (2007), Arab culture and the novel: genre, identity and agency in Egyptian fiction, Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-77260-0

- Skovgaard-Petersen, Jakob (1997), Defining Islam for the Egyptian state: muftis and fatwas of the Dār al-Iftā, Brill, ISBN 978-90-04-10947-6

- Summerfield, Carol; Devine, Mary; Levi, Anthony, eds. (1998), International Dictionary of University Histories, Taylor & Francis, ISBN 978-1-884964-23-7

- Tracy, James D., ed. (2000), City walls: the urban enceinte in global perspective, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-65221-6

- Viorst, Milton (2001), In the shadow of the Prophet: the struggle for the soul of Islam, Westview Press, ISBN 978-0-8133-3902-3

- Voll, John Obert (1994), Islam, continuity and change in the modern world: Contemporary issues in the Middle East, Syracuse University Press, ISBN 978-0-8156-2639-8

- Watson, William E. (2003), Tricolor and crescent: France and the Islamic world; Perspectives on the twentieth century, Greenwood Publishing Group, ISBN 978-0-275-97470-1

- Williams, Caroline (2002), Islamic Monuments in Cairo, American University in Cairo Press, ISBN 978-977-424-695-1

- Winter, Michael (2004), Egyptian Society Under Ottoman Rule, 1517–1798, Routledge, ISBN 978-0-203-16923-0

- Yeomans, Richard (2006), The art and architecture of Islamic Cairo, Garnet & Ithaca Press, ISBN 978-1-85964-154-5

- Zaman, Muhammad Qasim (2002), The ulama in contemporary Islam: custodians of change, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-09680-3