This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Tesseract2 (talk | contribs) at 18:45, 4 September 2010 (fixing links). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

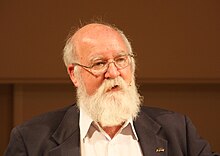

Revision as of 18:45, 4 September 2010 by Tesseract2 (talk | contribs) (fixing links)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)| Daniel Clement Dennett | |

|---|---|

| Born | (1942-03-28) March 28, 1942 (age 82) Boston, Massachusetts |

| Alma mater | Harvard University University of Oxford |

| Era | 20th / 21st-century philosophy |

| Region | Western Philosophy |

| School | Analytic philosophy |

| Main interests | Philosophy of mind Philosophy of biology Philosophy of science |

| Notable ideas | Heterophenomenology Intentional stance Intuition pump Multiple Drafts Model Greedy reductionism |

Daniel Clement Dennett (born March 28, 1942 in Boston) is an American philosopher and cognitive scientist whose research centers on the philosophy of mind, philosophy of science and philosophy of biology, particularly as those fields relate to evolutionary biology and cognitive science. He is currently the co-director of the Center for Cognitive Studies, the Austin B. Fletcher Professor of Philosophy, and a University Professor at Tufts University. Dennett is a noted atheist and secularist, a member of the Secular Coalition for America advisory board, as well as a prominent advocate of the Brights movement.

Early life and education

Dennett spent part of his childhood in Lebanon, where, during World War II, his father was a covert counter-intelligence agent with the Office of Strategic Services posing as a cultural attaché to the American Embassy in Beirut. The young Dennett and family returned to Massachusetts in 1947 after his father died in an unexplained plane crash. His sister is the investigative journalist Charlotte Dennett.

He attended Phillips Exeter Academy and spent one year at Wesleyan University before receiving his B.A. in philosophy from Harvard University in 1963, where he was a student of W.V. Quine. In 1965, he received his D.Phil in philosophy from Hertford College, Oxford, where he studied under the ordinary language philosopher Gilbert Ryle.

Career in academia

Dennett is currently (April 2009) the Austin B. Fletcher Professor of Philosophy, University Professor, and Co-Director of the Center for Cognitive Studies (with Ray Jackendoff) at Tufts University.

Dennett describes himself as "an autodidact — or, more properly, the beneficiary of hundreds of hours of informal tutorials on all the fields that interest me, from some of the world's leading scientists."

Dennett gave the John Locke lectures at the University of Oxford in 1983, the Gavin David Young Lectures at Adelaide, Australia, in 1985, and the Tanner Lecture at Michigan in 1986, among many others. In 2001 he was awarded the Jean Nicod Prize and gave the Jean Nicod Lectures in Paris. He has received two Guggenheim Fellowships, a Fulbright Fellowship, and a Fellowship at the Center for Advanced Studies in Behavioral Science. He was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1987. He was the co-founder (1985) and co-director of the Curricular Software Studio at Tufts University and has helped to design museum exhibits on computers for the Smithsonian Institution, the Museum of Science in Boston, and the Computer Museum in Boston. He is a Humanist Laureate of the International Academy of Humanism and a Fellow of the Committee for Skeptical Inquiry. The American Humanist Association named him the 2004 Humanist of the Year.

Free will

While he is a confirmed Compatibilist on free will, in "On Giving Libertarians What They Say They Want" - Chapter 15 of his 1978 book Brainstorms, Dennett articulated the case for a two-stage model of decision making in contrast to libertarian views.

The model of decision making I am proposing has the following feature: when we are faced with an important decision, a consideration-generator whose output is to some degree undetermined produces a series of considerations, some of which may of course be immediately rejected as irrelevant by the agent (consciously or unconsciously). Those considerations that are selected by the agent as having a more than negligible bearing on the decision then figure in a reasoning process, and if the agent is in the main reasonable, those considerations ultimately serve as predictors and explicators of the agent's final decision.

While other philosophers have developed two-stage models, including William James, Henri Poincaré, Arthur Holly Compton, and Henry Margenau, Dennett defends this model for the following reasons:

- First...The intelligent selection, rejection, and weighing of the considerations that do occur to the subject is a matter of intelligence making the difference.

- Second, I think it installs indeterminism in the right place for the libertarian, if there is a right place at all.

- Third...from the point of view of biological engineering, it is just more efficient and in the end more rational that decision making should occur in this way.

- A fourth observation in favor of the model is that it permits moral education to make a difference, without making all of the difference.

- Fifth — and I think this is perhaps the most important thing to be said in favor of this model — it provides some account of our important intuition that we are the authors of our moral decisions.

- Finally, the model I propose points to the multiplicity of decisions that encircle our moral decisions and suggests that in many cases our ultimate decision as to which way to act is less important phenomenologically as a contributor to our sense of free will than the prior decisions affecting our deliberation process itself: the decision, for instance, not to consider any further, to terminate deliberation; or the decision to ignore certain lines of inquiry.

These prior and subsidiary decisions contribute, I think, to our sense of ourselves as responsible free agents, roughly in the following way: I am faced with an important decision to make, and after a certain amount of deliberation, I say to myself: "That's enough. I've considered this matter enough and now I'm going to act," in the full knowledge that I could have considered further, in the full knowledge that the eventualities may prove that I decided in error, but with the acceptance of responsibility in any case.

Leading libertarian philosophers such as Robert Kane have rejected Dennett's model, specifically that random chance is directly involved in a decision, which eliminates the agent's motives and reasons, character and values, and feelings and desires. They claim that if chance is the primary cause of decisions, then agents cannot be liable for resultant actions.

Dennett and Kane agree that their models do not find the appropriate location in the brain for randomness that will only help and not hurt a model of free will that provides agent control. Kane says:

a causal indeterminist view of this deliberative kind does not give us everything libertarians have wanted from free will. For does not have complete control over what chance images and other thoughts enter his mind or influence his deliberation. They simply come as they please. does have some control after the chance considerations have occurred.

But then there is no more chance involved. What happens from then on, how he reacts, is determined by desires and beliefs he already has. So it appears that he does not have control in the libertarian sense of what happens after the chance considerations occur as well. Libertarians require more than this for full responsibility and free will.

Other philosophical views

Dennett has remarked in several places (such as "Self-portrait", in Brainchildren) that his overall philosophical project has remained largely the same since his time at Oxford. He is primarily concerned with providing a philosophy of mind that is grounded in empirical research. In his original dissertation, Content and Consciousness, he broke up the problem of explaining the mind into the need for a theory of content and for a theory of consciousness. His approach to this project has also stayed true to this distinction. Just as Content and Consciousness has a bipartite structure, he similarly divided Brainstorms into two sections. He would later collect several essays on content in The Intentional Stance and synthesize his views on consciousness into a unified theory in Consciousness Explained. These volumes respectively form the most extensive development of his views.

In Consciousness Explained, Dennett's interest in the ability of evolution to explain some of the content-producing features of consciousness is already apparent, and this has since become an integral part of his program. He defends a theory known by some as Neural Darwinism. He also presents an argument against qualia; he argues that the concept is so confused that it cannot be put to any use or understood in any non-contradictory way, and therefore does not constitute a valid refutation of physicalism. Much of Dennett's work since the 1990s has been concerned with fleshing out his previous ideas by addressing the same topics from an evolutionary standpoint, from what distinguishes human minds from animal minds (Kinds of Minds), to how free will is compatible with a naturalist view of the world (Freedom Evolves). In his 2006 book, Breaking the Spell: Religion as a Natural Phenomenon, Dennett attempts to subject religious belief to the same treatment, explaining possible evolutionary reasons for the phenomenon of religious adherence.

Dennett self-identifies with a few terms:

note that my 'avoidance of the standard philosophical terminology for discussing such matters' often creates problems for me; philosophers have a hard time figuring out what I am saying and what I am denying. My refusal to play ball with my colleagues is deliberate, of course, since I view the standard philosophical terminology as worse than useless — a major obstacle to progress since it consists of so many errors.

— Daniel Dennett, The Message is: There is no Medium

Yet, in Consciousness Explained, he admits "I am a sort of 'teleofunctionalist', of course, perhaps the original teleofunctionalist'". He goes on to say, "I am ready to come out of the closet as some sort of verificationist". In Breaking the Spell: Religion as a Natural Phenomenon he admits to being "a bright", and defends the term.

Role in evolutionary debate

Dennett sees evolution by natural selection as an algorithmic process (though he spells out that algorithms as simple as long division often incorporate a significant degree of randomness). This idea is in conflict with the evolutionary philosophy of paleontologist Stephen Jay Gould, who preferred to stress the "pluralism" of evolution (i.e. its dependence on many crucial factors, of which natural selection is only one).

Dennett's views on evolution are identified as being strongly adaptationist, in line with his theory of the intentional stance, and the evolutionary views of biologist Richard Dawkins. In Darwin's Dangerous Idea, Dennett showed himself even more willing than Dawkins to defend adaptationism in print, devoting an entire chapter to a criticism of the ideas of Gould. This stems from Gould's long-running public debate with E. O. Wilson and other evolutionary biologists over human sociobiology and its descendant evolutionary psychology, which Gould and Richard Lewontin opposed, but which Dennett advocated, together with Dawkins and Steven Pinker. Strong disagreements have been launched against Dennett from Gould and his supporters, who allege that Dennett overstated his claims and misrepresented Gould's to reinforce what Gould describes as Dennett's "Darwinian fundamentalism".

Dennett's theories have had a significant influence on the work of evolutionary psychologist Geoffrey Miller. He has also written about and advocated the notion of memetics as a philosophically useful tool, most recently in his "Brains, Computers, and Minds," a three part presentation through Harvard's MBB 2009 Distinguished Lecture Series.

Personal life

Dennett lives with his wife in North Andover, Massachusetts, and has a daughter, a son, and two grandsons. He is also an avid sailor.

In October 2006, Dennett was hospitalized due to an aortic dissection. After a nine-hour surgery, he was given a new aorta. In an essay posted on the Edge website, Dennett gives his firsthand account of his health problems, his consequent feelings of gratitude towards the scientists and doctors whose hard work made his recovery possible, and his complete lack of a "deathbed conversion". By his account, upon having been told by friends and relatives that they had prayed for him, he resisted the urge to ask them, "Did you also sacrifice a goat?"

Selected books

- Brainstorms: Philosophical Essays on Mind and Psychology (MIT Press 1981) (ISBN 0-262-54037-1)

- Elbow Room: The Varieties of Free Will Worth Wanting (MIT Press 1984) — on free will and determinism (ISBN 0-262-04077-8)

- The Mind's I (Bantam, Reissue edition 1985, with Douglas Hofstadter) (ISBN 0-553-34584-2)

- Content and Consciousness (Routledge & Kegan Paul Books Ltd; 2nd ed. January 1986) (ISBN 0-7102-0846-4)

- Daniel C. Dennett (1996), The Intentional Stance (6th printing), Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press, ISBN 0-262-54053-3 (First published 1987)

- Consciousness Explained (Back Bay Books 1992) (ISBN 0-316-18066-1)

- Darwin's Dangerous Idea: Evolution and the Meanings of Life (Simon & Schuster; reprint edition 1996) (ISBN 0-684-82471-X)

- Kinds of Minds: Towards an Understanding of Consciousness (Basic Books 1997) (ISBN 0-465-07351-4)

- Brainchildren: Essays on Designing Minds (Representation and Mind) (MIT Press 1998) (ISBN 0-262-04166-9) — A Collection of Essays 1984–1996

- Freedom Evolves (Viking Press 2003) (ISBN 0-670-03186-0)

- Sweet Dreams: Philosophical Obstacles to a Science of Consciousness (MIT Press 2005) (ISBN 0-262-04225-8)

- Breaking the Spell: Religion as a Natural Phenomenon (Penguin Group 2006) (ISBN 0-670-03472-X).

- Neuroscience and Philosophy: Brain, Mind, and Language (Columbia University Press 2007) (ISBN 978-0-231-14044-7), co-authored with Maxwell Bennett, Peter Hacker, and John Searle

- Science and Religion (Oxford University Press 2010) (ISBN 0-199-73842-4), co-authored with Alvin Plantinga

See also

- The Atheism Tapes

- Cartesian materialism

- Conscious Robots

- Evolutionary psychology of religion

- Greedy reductionism

- Geoffrey Miller (evolutionary psychologist)

- Heterophenomenology

- Intentional stance

- List of Jean Nicod Prize laureates

- Memetics

- Multiple drafts theory of consciousness

- Philosophy of Religion

- American philosophy

- List of American philosophers

Further reading

- John Brockman (1995). The Third Culture. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-684-80359-3 (Discusses Dennett and others).

- Daniel C. Dennett (1997), "Chapter 3. True Believers: The Intentional Strategy and Why it Works", in John Haugeland, Mind Design II: Philosophy, Psychology, Artificial Intelligence. Massachusetts: Massachusetts Institute of Technology. ISBN 0-262-08259-4 (reprint of 1981 publication).

- Andrew Brook and Don Ross (editors) (2000). Daniel Dennett. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-00864-6

- Don Ross, Andrew Brook and David Thompson (editors) (2000) Dennett's Philosophy: A Comprehensive Assessment Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-18200-9

- John Symons (2000) On Dennett. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing Company. ISBN 0-534-57632-X

- Matthew Elton (2003). Dennett: Reconciling Science and Our Self-Conception. Cambridge, U.K: Polity Press. ISBN 0-7456-2117-1

- P.M.S. Hacker and M.R. Bennett (2003) Philosophical Foundations of Neuroscience. Oxford, and Malden, Mass: Blackwell ISBN 1-4051-0855-X (Has an appendix devoted to a strong critique of Dennett's philosophy of mind)

Notes

a. "True Believers: The Intentional Strategy and Why it Works" is a reprint of paper first published in 1981 in Scientific Explanation, edited by A.F. Heath (Oxford: Oxford University Press). The paper was originally presented as a Herbert Spencer lecture at Oxford in November 1979. It was also published as chapter 2 in Dennett's book The Intentional Stance (see further reading above).

References

- Secular Coalition for America Advisory Board Biography

- ^ Feuer, Alan (2007-10-23), "A Dead Spy, a Daughter's Questions and the C.I.A.", New York Times, retrieved 2008-09-16

- Brown, Andrew (2004-04-17). "The semantic engineer". The Guardian. Retrieved 2010-02-01.

- Center for Cognitive Studies

- Dennett, Daniel C. (2005-09-13) , "What I Want to Be When I Grow Up", in John Brockman (ed.), Curious Minds: How a Child Becomes a Scientist, New York: Vintage Books, ISBN 1-4000-7686-2

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Brainstorms: Philosophical Essays on Mind and Psychology, MIT Press (1978), pp.286-299

- Brainstorms, p.295

- Brainstorms, pp.295-97

- Robert Kane, A Contemporary Introduction to Free Will, Oxford (2005) p.64-5

- Guttenplan, Samuel (1994), A companion to the philosophy of mind, Oxford: Blackwell, p. 642, ISBN 0-631-19996-9

- p. 52-60, Darwin's Dangerous Idea: Evolution and the Meanings of Life (Simon & Schuster; reprint edition 1996) (ISBN 0-684-82471-X)

- Although Dennett has expressed criticism of human sociobiology, calling it a form of "greedy reductionism", he is generally sympathetic towards the explanations proposed by evolutionary psychology. Gould also is not one sided, and writes: "Sociobiologists have broadened their range of selective stories by invoking concepts of inclusive fitness and kin selection to solve (successfully I think) the vexatious problem of altruism—previously the greatest stumbling block to a Darwinian theory of social behavior. . . . Here sociobiology has had and will continue to have success. And here I wish it well. For it represents an extension of basic Darwinism to a realm where it should apply." Gould, 1980. "Sociobiology and the Theory of Natural Selection" In G. W. Barlow and J. Silverberg, eds., Sociobiology: Beyond Nature/Nurture? Boulder CO: Westview Press, pp. 257-269.

- 'Evolution: The pleasures of Pluralism' — Stephen Jay Gould's review of Darwin's Dangerous Idea, June 26, 1997

- Daniel C. Dennett's Home Page

- Richard Dawkins: 'The Genius of Charles Darwin' (2008.).

- 'Thank Goodness!', edge 195, Nov. 3, 2006

External links

- Faculty webpage

- Scientific American Frontiers Profile: Daniel Dennett 2000-12-19

- Searchable bibliography of Dennett's works

- Daniel Dennett on Information Philosopher

- "Daniel Dennett: Autobiography (part 1)"

- Media

- Edge/Third Culture: Daniel C. Dennett

- Daniel Dennett multimedia files

- Profile at TED several videos on dangerous memes, consciousness, others

- Radio interview on Philosophy Talk 2006-01-17

- The Nature of Knowledge Lecture at the University of Edinburgh 2006-03-14

- On Preaching and Teaching The Science Network interview with Daniel Dennett 2007-11-02

- The Moscow Center for Consciousness Studies video interview with Daniel Dennett 2010-03-05

| Daniel Dennett | ||

|---|---|---|

| Concepts |  | |

| Selected works |

| |

| Other | ||

| Analytic philosophy | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Related articles |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Theories | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Concepts |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Philosophers |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Philosophy of mind | |

|---|---|

| Philosophers |

|

| Theories |

|

| Concepts |

|

| Related | |

| Philosophy of religion | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concepts in religion | |||||||||||||

| Conceptions of God |

| ||||||||||||

| Existence of God |

| ||||||||||||

| Theology |

| ||||||||||||

| Religious language | |||||||||||||

| Problem of evil | |||||||||||||

| Philosophers of religion (by date active) |

| ||||||||||||

| Related topics | |||||||||||||

| Philosophy of science | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Concepts |

| ||

| Theories |

| ||

| Philosophy of... | |||

| Related topics |

| ||

| Philosophers of science |

| ||

|

| |||

- 1942 births

- 20th-century philosophers

- 21st-century philosophers

- American atheists

- American philosophers

- Analytic philosophers

- Atheist philosophers

- Atheism activists

- Cognitive scientists

- Consciousness researchers and theorists

- Phillips Exeter Academy alumni

- Wesleyan University alumni

- Harvard University alumni

- Alumni of Christ Church, Oxford

- Living people

- Memetics

- People from Boston, Massachusetts

- Philosophers of mind

- Philosophers of religion

- Philosophers of science

- Tufts University faculty

- Fellows of the Association for the Advancement of Artificial Intelligence

- Jean Nicod Prize laureates

- American non-fiction writers

- Fellows of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences

- Evolutionary psychologists