This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Michael Paul Heart (talk | contribs) at 09:04, 7 January 2011 (→Biblical Translations: typo). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 09:04, 7 January 2011 by Michael Paul Heart (talk | contribs) (→Biblical Translations: typo)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)| This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

No issues specified. Please specify issues, or remove this template. (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

| This article needs attention from an expert in bible. Please add a reason or a talk parameter to this template to explain the issue with the article. WikiProject Bible may be able to help recruit an expert. (December 2010) |

| Part of a series on the | |||

| Bible | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

|

|||

|

|||

Biblical studies

|

|||

| Interpretation | |||

| Perspectives | |||

|

Outline of Bible-related topics | |||

Tahash or Tachash, (Hebrew: תחש) is the source of 'orot tahashim (Hebrew: וערות תחשים), referred to in the Bible, used as the outer covering of the Tabernacle and to wrap sacred objects used within the Tabernacle for transport. Tahash is traditionally interpreted to be an animal, with 'orot tahashim being tahash skins or leather. Sages, scholars and linguists have debated the Biblical meaning of תחשים for centuries.

Proposed translations

Literal translation

Tachash, extremely literally, is translated as:

- תאה — tah —"circumscribed", "set apart/marked/distinct", "very/markedly/distinctively"—plus

- חש — khoosh, hish — "swift/quick" / "dark/black/hide(away)"—literally: —ת - הש / ת - חש— :

- תחש — tah-hash, takh-ash — "very swift" / "richly, distinctively black", "truly reserved", "deep dark retreating".

Tachash skins are "skins of astonishment (quick)" and "skins of reserved dark retreat (hiding)".

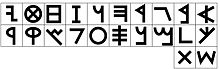

Etymology shows that in over 45 centuries a semantic change has occurred in the meaning of Hebrew tahas. Its pronunciation has changed, from Biblical to Israeli (Hebrew phonology). Its spelling has changed, from Phoenician ![]()

![]()

![]() to Masoretic תחש. The English form of the word has also changed, from tachash to tahash.

to Masoretic תחש. The English form of the word has also changed, from tachash to tahash.

Animal

Traditionally, the word Tachash has been translated to be an animal, the species of which is a matter of some debate.

In the Jewish tradition, Rashi writes that the tachash was a kosher, multi-colored, one-horned desert animal which came into existence to be used to build the Tabernacle and ceased to exist afterward. Others believe the tachash was related to the keresh, a creature most often identified with the giraffe.

The King James Version of the Bible translates the word tachash as badger (from the Latin Meles taxus, and the German dachs).

A popular hypothesis of the early- to mid-20th century proposed that the term "tachash" means dugong. This translation is based upon the similarity between tachash and the Arabic word tukhas or tukhesh ( البدر / دلفبن ), which means dugong. In accordance with this hypothesis several translations, such as the Jewish Publication Society translation, render tachash as dolphin or sea cow.

The New American Bible (USCCB) (1971) translates 'orot tachashim literally as "tahash skins" (Exodus 25:5):

- "5 rams' skins dyed red, and tahash skins; acacia wood;"

Compare Biblical translations of תחשים ←(m'-s-h-t←) in Exodus 25:5 "tahash" (NAB) "badgers" (KJV)

Compare Biblical translations of תחש ←(s-h-t←) in Ezekiel 16:10 "fine leather" (NAB) "badger" (KJV)

Processes & color

Another hypothesis is that the Hebrew term וערות תחשים / " 'orot t'chash'm" / " 'oroth t'hash'm" refers to very fine dyed leather (of sheep or goats) rather than the skins of an unusual animal. Witnesses before the 1st century BCE understood skins of tahashim to be fine leather work dyed blue, indigo, purple, violet. Such documented interpretations and translations of Biblical Hebrew תחש, tahas, t-ch-sh, from classical antiquity together with increased knowledge of the ancient tongues have strongly influenced recent Bible translators.

In keeping with this scholarship the Jerusalem Bible translates the term as "fine leather".

Navigating the Bible II (World ORT) (2006), translates 'orot tahasim as "blue-processed skins."

Recent scholarship (2000–2006) says that the term denotes neither a substance nor a color, but a technique of sewing blue faience beads onto leather, making "beaded skins" the meaning of 'oroth T'Hash'm.

—small blue-green beads.

Biblical Translations

- The Scrollscraper Tikkun (2006–2010) transliterates tahas (t'hasim) as tchash (ve'orot tchashim).

- The Judaica Press Complete Tanach (Chabad.org) (2006–2010) transliterates tahas (t'hasim) as tachash (tachashim).

- The Navigating the Bible II World ORT translation (2006–2008) translates tahas (t'hasim) as blue-processed (skins).

- The Living Torah by Aryeh Kaplan (bible.ort.org) (2006) translates tahas (t'hasim) as blue-processed (skins).

- The Anchor Bible: Exodus 19-40: Volume 2A (2006) translates tahas (t'hasim) as beaded (beaded skins).

- The English Standard Version (ESV) (2001-2009 revision of 1971 RSV) translates tachash as goat (goatskins).

- The American King James Version (AKJV) (1999 version of 1769 KJV) translates tachash as badger (badger's skins).

- The World English Bible (WEB) (1997-2000 version of 1901 ASV) translates tachash as sea cow (sea cow hides).

- The God's Word Translation (GW) (1995) translates tachash as fine leather.

- The New American Bible (NAB) (1991–2005) renders tachash as tahash.

- The New Revised Standard Version (NRSV) (1989–2005) translates tachash as fine leather.

- The New King James Version (NKJV) (1989) translates tachash as badger (badger's skins).

- The Revised English Bible (REB) (1989) translates tachash as dugong (dugong-hides).

- The New Jerusalem Bible (NJB) (1985) translates tachash as fine leather.

- The New Jewish Publication Society translation (JPS Tanakh) (1985) translates tachash as dolphin, or sea cow.

- The New International Version (NIV) (1978) translates tachash as sea cow (sea cow hides).

- The New American Standard Bible (NASB) (1971–1995) translates tachash as porpoise (porpoise skins).

- The New World Translation (NWT) (1961) translates tachash as seal (sealskins).

- The Revised Standard Version (RSV) (1952–2000) translates tachash as goat (goatskins).

- The Bible in Basic English (BBE) (1949–1965) translates tachash as leather.

- The Jewish Publication Society of America Version (JPS) (1917) translates tachash as badger (badgers' skins).

- The American Standard Version (ASV) (1901) translates tachash as seal (sealskins).

- Young's Literal Translation (1862–1898) translates tachash as badger (badgers' skins).

- The Authorized King James Version (AV, KJV) (1611–1769) translates tachash as badger (badgers' skins).

- The Douay-Rheims Bible (Douai, D-R, DV) (1610–1750) translates tachash as violet (violet skins).

- Abraham Maimon HaNagid (13th century) translates tachash as black leather (dark blue skins, skins rendered dark and waterproof).

- Rashi's commentary (12th century) translates tachash as taisse (badger) from Greek τρόχος (runner).

- The Arukh compiled by Nathan ben Jehiel (11th-12th century) translates tachash as blue-processed (blue-processed skins).

- Jonah ibn Janah (11th century) translates tachash as black leather (dark blue skins).

- Saadia Gaon (10th century) translates tachash as black leather (dark blue skins).

- The Latin Vulgate (L.V.) (405) translates tachash as ianthinas, violet (violet skins).

- The Mishnah (Mish.): Tanna Rabbi Judah ha-Nasi (170-220) translates tachash as altinon (Greek, aledinon), purple (skins dyed purple).

- The Targum Jonathan (110-170) translates tachash as khn כהניא (glory), i.e. the color of heaven.

- The Targum Onkelos (Tar. Onq.) (110) translates tachash as ssgwn ססגונא (sas-gona, sas-gavna), i.e. joy (of all) colors, glowing (of) colors, radiant(-like worm-)colors, (most) blessed (of) colors, richest (of) colors, royal color (?)---(glory-colored skins?).

- The Antiquities of the Jews (93-4 CE) interprets the curtains of tachash skins as curtains made of skins the color of the sky.

- The Septuagint (LXX) (3rd to 1st century BCE) translates tachash as huakinthina, hyacinth (indigo-blue) (hyacinth skins).

Animals

In many traditions, Tahash refers to an animal. The various proposed animals include: badger, dugong, sea cow, seal, narwhal, porpoise, dolphin, addax, antelope, giraffe, okapi, the extinct Elasmotherium, and others.

Unclean (non-kosher) animals

The Hebrew words tahash and tahashim in the Bible (for example, Numbers 4) are translated by the King James Version (KJV) as "badger". The New American Standard Bible (NASB) translates the word as porpoise. Other translations include dugong, sea cow, seal, and dolphin. Although these animals are not kosher (not clean) it has been suggested that the Tabernacle may have been purposefully constructed using skin from a non-kosher (unclean) animal. These suggestions date from the time of the formation of the Talmud beginning around the 4th century CE and continue through the centuries to the present. —see Importance of textual and cultural and religious context.

Sea mammals

The scholarly opinion which prevailed for most of the 19th and 20th centuries (1820–1980), even if it was not the universal consensus, held that Hebrew t-h-sh / t-kh-sh / t-ch-sh, English tahash, "correctly" or "most probably" denoted dugong or sea cow or manatee or mediterranean monk seal or porpoise or dolphin. The older 19th century scientific names (taxonomy) for the Dugong took account of this view: E. Rupell designated them Halicore Tabernaculi in 1843. This opinion is now declining, as witness the more recent translations of the Hebrew Scriptures (Tanakh). (see 'Biblical Translations', and Encyclopaedia Judaica, Second Edition, 2007: "Tahash".')

The Arabic البدر / دلفبن dukhas or tukhas or tucash is linguistically near to Hebrew תחש takhash or tachash or tahash, and is applied by the Arabs to the dugong and the dolphin, which is also called delphin, and also to the porpoise. Prompted by the similarity to Arabic tukhash, conjectural opinion has favored identification of tahash with the sea cow, a species now extinct. Fossils indicate that Stellar's Sea Cow (Hydrodamalis gigas) was formerly abundant and widespread throughout the North Pacific, all along the North Pacific Coast, reaching west and south to Japan and east and south to California. There is no evidence that the now extinct sea cow ever ranged over the Red Sea area. The term sea cow more generally refers to dugongs and manatees, to any of the sirenian sea mammals including the larger seals that appear on the shores of East Africa and around the Sinai peninsula. The Arabic البدر tukhesh denotes the sea mammal Dugong hemprichi, (the same animal formerly designated Halicore Tabernaculi) which appears at intervals on the shores of the Sinai and is hunted by the Bedouin, who make tent curtains and shoes from its skin.

Another opinion suggests that tahash should be identified with the the narwhal. However the narwhal is generally only found in the arctic, and suggestions that it has previously been found in the Mediterranean are not supported by any available evidence.

Clean (kosher) animals

Among the kosher animals proposed as translations of tahash are the Addax, the antelope, the sheep, the goat, and the giraffe.

The giraffe has generally been excluded as the meaning of tahash, in part because of a question of whether or not it possessed all the marks of a kosher animal, and because its range was primarily Sub-Saharan Africa, from Chad in Central Africa to South Africa. The distance that would have to be traversed in migration away from its natural range and habitat can be seen in this image of the Sahara Desert, the Red Sea, and the desert of the Sinai peninsula. Nevertheless, there is some evidence that camelopardalis, the giraffe, was also present in the Levant at the time of Moses; and there is documented evidence that it has all the marks of a kosher animal.

Process

Several translations propose that "orot t'chash'm" refers to very fine dyed sheepskin or goat leather. This is in preference to assuming a cryptid such as the Elasmotherium. Translating "orot t'chash'm" as "blue-processed skins" is parallel with "rams' skins dyed red." The resultant color of the process according to the Greek and Latin translations was hyacinth. According to this interpretation, the text of Exodus 26:14 means "a covering of rams' skins dyed red, and above that a covering of hyacinth skins"—a covering of skins dyed red and an outer covering of skins dyed indigo or royal blue.

Royal Blue

#002366

Indigo

#4B0082

Wilhelm Gesenius (pub. Leipzig, 1905) cites J. H. Bondi (Aegyptiaca, i.ff) proposing the Egyptian root t-ch-s, making the expression " 'or tahash / 'or tachash" mean "soft-dressed skin" (fine leather work). The final stage of tanning called "crusting" includes dying with color. A vat full of indigo dye is a very dark color called "midnight blue" which is almost black. Tekhelet blue has been referred to as being "black as midnight", "blue as the midday sky", and as purple.

According to the Sages (Baba Metzia 61b) techelet blue is identical in color to kela ilan (indigofera tinctoria) indigo dye.

According to Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews, Book 3:6:4 (Ant. 3.132), the outer covering of skins over the tabernacle "seemed not at all to differ from the color of the sky".

Etymology

This article traces the changes in meaning of the word "tahash" by means of a timeline of history. Its purpose is to show what its meaning has been in the past and what its meaning is today, and not to determine its "true" meaning. The assertion that the "true" meaning of a word is to be sought in its etymology is a variant of the etymological fallacy. The several meanings that it has today are listed in the Summary at the end of this article.

Etymology is the study of the history of words and how their form and meaning have changed over time (see especially Semantic change.) For languages with a long written history, etymologists make use of texts in those languages, and texts about the languages, to gather knowledge about how words were used at earlier stages, and where and when and how they entered the languages in question. The methods of comparative linguistics are also applied to reconstruct information about languages that are too old for any direct information to be available. Making use of "dialectological" data, the form or meaning of the word might show variation between dialects which may yield clues of its earlier history (e.g. tachash and tukhash). (see dialectology, comparative method, historical linguistics, comparative linguistics and pseudoscientific language comparison; also false etymology.)

Akkadian

t-h-s appears cognate with Akkadian dusu / tuhsia "goat/sheep leather ."

t-h-s-m appears connected to an Assyrian word meaning "sheepskin" and an Egyptian word meaning "to stretch or treat leather."

Egyptian

Modern scholarship sees Hebrew tahash as derived best from the old Egyptian word tj-h-s, "to treat leather." Wilhelm Gesenius (1848–50) shows J. H. Bondi (Aegyptiaca, iff) proposing the Egyptian root t-ch-s, making the Hebrew term 'or tahash— — mean "soft-dressed skin".

Reading from right to left ←

Ancient witnesses attest the translation of 'orot tahashim as "blue-processed skins" (Rabbi Yehudah, Yerushalmi, Shabbath 2:3; Arukh s.v. Teynun; Koheleth Rabbah 1:9; Josephus 3:6:1 (3.102), 3:6:4 (3.132); Septuagint (LXX); Aquila huakinthinos). Avraham ben HaRambam (Rambam) renders orot tahashim as "black leather", as do Saadia Gaon and Jonah ibn Janah—leather specially worked so as to become dark and waterproof. Josephus says in the third book of his work Antiquities of the Jews, chapter 3:

- There were also curtains made of skins above these, which afforded covering and protection to those that were woven, both in hot weather and when it rained; and great was the surprise of those who viewed these curtains at a distance, for they seemed not at all to differ from the color of the sky; but those that were made of hair and of skins, reached down in the same manner as did the veil at the gates, and kept off the heat of the sun, and what injury the rains might do, and after this manner was the tabernacle reared.

These ancient sources translate 'orot tahashim (derived from Egyptian tj-h-s) as blue-processed skins, dark and waterproof, which were used to make curtains of skins as covering and protection over the Mishkan. Modern Bible translators have also rendered 'orot tahashim as colored skins or leather.

The Douay-Rheims 1899 American Edition Catholic Bible translates the outer skins of the tabernacle as "violet skins".

The World ORT Navigating the Bible II (2006–2008) and The Living Torah by Aryeh Kaplan (bible.ort.org) translate the outer skins of the Mishkan as "blue-processed skins".

see above —Bible Translations

Semitic

Some scholars, such as S. M. Perlmann, have suggested that the tahash is a kosher animal with fur, such as the okapi, a kind of African "antelope", taking תחש tachash from חש "hish" (fleet, swift):

- חש –a primitive root; to hurry; figuratively to be eager with excitement or enjoyment; (make) haste (hasten), ready; also readiness; to be necessary, to need; necessity; to restrain, refrain, remove (oneself), to (willingly) be removed; by implication, to refuse, spare, preserve, to observe (from a distance, carefully); assuage, darken, forebear, hinder, hold back, keep (back); punish, reserve, spare, withhold; to be dark (as withholding light); to darken, be black, be (or make) dark, cause darkness, be dim, hide; the dark, darkness, misery, destruction, death, ignorance, sorrow, wickedness, night, obscurity; obscure, mean (hidden, unnoticed).

Hebrew 20th to 4th centuries BCE

The Hebrew alphabet is an abjad, or consonant-only script of 22 letters. The ancient Paleo-Hebrew alphabet is similar to those used for Canaanite and Phoenician. Because of the lack of vowel letters, unambiguous reading of the most ancient texts is difficult, often inconclusive, often speculative, resulting in variant readings and interpretations of meaning (and copious footnotes.) This is important for understanding the ancient written forms of ( 'orot tehasim) tehasim: — ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() —

— ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() —

— ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() —

— ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() — ת ח ש ם — MSHT / THSM — t-ch-sh-m — before the establishment of the Masoretic Text. The more ancient Hebrew spelling of primitive Semitic root-words does not include consonant letters as matres lectionis before c. 1000 BCE (see origins and development).

— ת ח ש ם — MSHT / THSM — t-ch-sh-m — before the establishment of the Masoretic Text. The more ancient Hebrew spelling of primitive Semitic root-words does not include consonant letters as matres lectionis before c. 1000 BCE (see origins and development).

See in the following order or sequence: Sumer, Proto-Semitic, Semitic languages, History of writing, Proto-Sinaitic alphabet, History of the alphabet, Phoenician alphabet, Northwest Semitic languages, Paleo-Hebrew alphabet, Archaic Biblical Hebrew, Biblical Hebrew, Samaritan Hebrew language, Samaritan script, Aramaic alphabet, Hebrew language.

| |

| The Northwest Semitic abjad | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Reconstructed ancestral form | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phoenician |

| Paleo-Hebrew alphabet | |

|---|---|

| |

| This article contains phonetic transcriptions in the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA). For an introductory guide on IPA symbols, see Help:IPA. For the distinction between , / / and ⟨ ⟩, see IPA § Brackets and transcription delimiters. |

Sound of letters Heth and He: Tachash and Tahash

The eighth letter of the Phoenician alphabet, Heth, originally represented a voiceless fricative, either a voiceless pharyngeal fricative /ħ/ or a voiceless velar fricative /x/ (the two Proto-Semitic phonemes having merged in Canaanite.) The sound of Archaic Biblical Hebrew Heth was phonetically very much closer to He than it is today (even the Hebrew letter forms, ancient and modern, are similar in appearance: ![]() ה

ה ![]() ח.)

ח.)

The Phoenician letter ![]() gave rise to the Greek Eta (H) and Latin H. While H is a vowel in the Greek alphabet, the Latin equivalent H represents a consonant sound, closer to Archaic Biblical Hebrew letter He ה

gave rise to the Greek Eta (H) and Latin H. While H is a vowel in the Greek alphabet, the Latin equivalent H represents a consonant sound, closer to Archaic Biblical Hebrew letter He ה ![]() . The sound of Archaic Biblical Heth ח

. The sound of Archaic Biblical Heth ח ![]() was also much closer to He ה

was also much closer to He ה ![]() than it is today. (For the ancient Biblical articulation of ח and ה see Hebrew phonology and voiceless pharyngeal fricative.) In Modern Israeli Hebrew, the historical phonemes of the letters Heth and Kaph have merged, both becoming voiceless uvular fricatives, making Heth more distant from He than anciently. The sound value of Kaph כ without the dagesh is the same as that of Heth ח. The Archaic Biblical sound values of Kaph, He, Heth are the same sound. There is a basic orthographic resemblance in the Archaic Biblical (Paleo-Hebrew) letters:

than it is today. (For the ancient Biblical articulation of ח and ה see Hebrew phonology and voiceless pharyngeal fricative.) In Modern Israeli Hebrew, the historical phonemes of the letters Heth and Kaph have merged, both becoming voiceless uvular fricatives, making Heth more distant from He than anciently. The sound value of Kaph כ without the dagesh is the same as that of Heth ח. The Archaic Biblical sound values of Kaph, He, Heth are the same sound. There is a basic orthographic resemblance in the Archaic Biblical (Paleo-Hebrew) letters: ![]() -

- ![]() -

- ![]() .

.

The etymology (historical development) of the Hebrew letter Heth presents a huge phonetic consonantal shift between the ancient and modern forms of its articulation or sound. The term THSM, tachashim תחשם (today pronounced "takh-ashim" or "tak-hashim" – תחשים), in ancient times pre-dating 500 BCE was pronounced "tah-ashim" or "tah-hashim". Hence, the rendering today of the word TAHASH (THS, tahas), in current English language dictionaries and encyclopedias, is put forth as a closer approximation of the ancient (actual) pronunciation.

In Modern Israeli Hebrew, the letter Heth / Khet / Chet may still be pronounced as a voiceless pharyngeal fricative among Mizrahim (especially among the older generation and popular Mizrahi singers), in accordance with oriental Jewish traditions, and with the still more ancient Biblical Hebrew form. Ancient Hebrew is also the liturgical tongue of the Samaritans. The Samaritans have continued to use the Old Hebrew alphabet to this day. The Semitic primitive root T'H, most anciently pronounced ta-, ta-ah-, ta-ha-, is now today usually pronounced ta-akh-, tehk-, tekh-heh-.

Pronunciation of the ancient primitive Semitic root: T-H = "ta'-ah, tah'-heh".

Tehom, Tekhelet, Tahashim, Tukhesh

"T-H-M, T-HoM"— ![]()

![]()

![]() —(from "H-M, HuwM"—

—(from "H-M, HuwM"— ![]()

![]() — make an uproar, agitate greatly: destroy, move, make noise)—tehom means abyss, a (deep) surging mass of water, the deep/deep place(s in the earth), depth, the depths, the main sea, subterreanean water-deep. From a Semitic primitive root T-H-, t-h-: "tah-, teh-, tah-hah-, teh-hoh-."

— make an uproar, agitate greatly: destroy, move, make noise)—tehom means abyss, a (deep) surging mass of water, the deep/deep place(s in the earth), depth, the depths, the main sea, subterreanean water-deep. From a Semitic primitive root T-H-, t-h-: "tah-, teh-, tah-hah-, teh-hoh-."

"T-H-l-t(h), T-kH-l-tH, T-Helet, T-kHeleth"—![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() —(phonetic rendering) — means blue, indigo, violet color (coloring or colors) like the deep color of the sea and the sky: also, any blue dye (see Semantic change.) This more broad and ancient general meaning is attested in later ancient sources: The Septuagint, Antiquities of the Jews 3.102, The Latin Vulgate, The Jerusalem Talmud Tractate Sabbath 2:3, The Mishnah Qohelet Rabba 1:9, and The Onkelos Targum ססגונא ssgvn. From a Semitic primitive root T-H-, t-ch-: "tah-, teh-, tach-, tehk-."

—(phonetic rendering) — means blue, indigo, violet color (coloring or colors) like the deep color of the sea and the sky: also, any blue dye (see Semantic change.) This more broad and ancient general meaning is attested in later ancient sources: The Septuagint, Antiquities of the Jews 3.102, The Latin Vulgate, The Jerusalem Talmud Tractate Sabbath 2:3, The Mishnah Qohelet Rabba 1:9, and The Onkelos Targum ססגונא ssgvn. From a Semitic primitive root T-H-, t-ch-: "tah-, teh-, tach-, tehk-."

The Hebrew Torah from the time of Moses to the time of Ezra (c. 459 BCE) says that the outer covering of the Mishkan is to be 'oroth T-Hashim, 'orot T-cHashim – -R-T-T-H-S-M –

וערות תחשים

——from 'or (eye-opening) 'orot (bared skins) + tahash + -im:

——from ta (circumscribe, reserve, designate) + hash (full, dark, deep) + im (multiple, most, intensely—doubtless, verily, truly):

——skins of tahasim: skins of "exalted-reserved-deep (mark or coloring)". (see below, "Suffix -im as the superlative form".) From a Semitic primary root T-H-, t-ch-: "tah-, teh-, tach-, tekh-."

The Arabs of the Sinai apply the description t-kh-sh, t-h-s, (Arabic)—![]()

![]()

![]() —

—![]()

![]()

![]() — tucash, tukhesh, tukhas to the dugong/manatee and other glaucous-colored sea mammals the Jews are commanded in the Torah to regard as unclean. From a Semitic primitive root T-H-, t-ch-: "tuh-, teh-, tukh-, tekh-."

— tucash, tukhesh, tukhas to the dugong/manatee and other glaucous-colored sea mammals the Jews are commanded in the Torah to regard as unclean. From a Semitic primitive root T-H-, t-ch-: "tuh-, teh-, tukh-, tekh-."

T-Hom, T-Helet, T-Hash, T-Hesh all share the same Semitic root.

m-h-t ![]()

![]()

![]() — t-l-qh-t

— t-l-qh-t ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() ,

, ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() — s-ch-t

— s-ch-t ![]()

![]()

![]() — s-kh-t

— s-kh-t ![]()

![]()

![]()

The primary root meanings of these four Semitic words (detailed above) indicate a relationship to a perceived color range of blue-gray-black the ancients associated with mystery and dignity: —"marked (great) deep" tehom, —"marked (from, of) the blue (depth)" tekheleth, tehelet —"marked (rich) dark/black" tahash, —"marked (of) dread/mystery (from the deep)" tukhesh: —all four words connoting "marked of heaven" (the removed, the distant, the set apart).

Charcoal

#36454F

Payne's grey

#40404F

Slate grey

#708090

Cool grey

#8C92AC

Purple taupe

#50404D

Midnight blue

#123245

Indigo dye

#00416A

Glaucous

#6082B6

These are the varying tukhesh colors and tones of the visual appearance of the skins of the dugongs and seals, and other sea mammals, as they appear both in the water and on and around the shores of the Sinai and Arabian peninsulas. The skins of antelopes can be dyed these colors: skins of gray, of blue, of tahash color.

Suffix -im as the superlative form

The Hebrew suffix -im added to a singular term normally renders it as a plural form of the word, but it may also indicate the superlative degree, as being of great dignity. For example, the singular word eloahh means "god" or "God", the plural form elohim normally means "gods", but when used of the one LORD it indicates the one God above all gods (Genesis 1:1.) With "tahash" as the singular form, and "tahashim" (T-H-S-M // M-S-H-T ת ח ש ם) as the singular superlative form, and the modifier of " 'orot (skins)", the expression "tahashim" can be read as a singular superlative term for color/finish raised to the superlative degree: (skins of) "exceeding/ exquisite/ glorious tahas": "T-Hashim": "Over the tent itself you shall make a covering of rams' skins dyed red, and above that a covering of (superlative) tahash skins--skins of (superlative) tahash (Tehelet dyed? beautifully beaded?) 'oroth T-Hashim."

Historical verification of the use of "-im" as the plural intensive singular (superlative) suffix of "tahash" is found in the fact that the Hebrew term tehasim was actually understood, up to and including the 5th century CE, as a color. (See below —Greek 3rd century to 1st century BCE, —Josephus 1st century CE, —Aramaic 2nd century CE, —Judah haNasi 3rd century, —Jerome 4th century.) —skins of hyacinth blue / indigo / violet.

Sacred word play: Paranomasia

Sacred word play is frequently found in the Bible, and is phonetically evident relating THSM תחשם and HSM השם by connotation: Tahashim and Hashem. Audio renderings of these words demonstrates their phonetic similarity. Hebrew spelling of these words without matres lectionis shows their orthographic similarity. Hebrew lexicons show the primitive roots which linguistically connect them. Word play in oral cultures, primitive and ancient and modern, is a method of reinforcing meaning. Compare the phonetic spelling (audio icon) of each of the following words most relevant here (also spelled with and without matres lectionis for graphic comparison):

- addax (specify English to Hebrew) דושון / דשן / דש

- 'adash אדש / דש (see Strong's number 156 and audio Strong's number 156)

- tachash תחש

- treads (tramples) דוש / דש

- grass דשא / דש

- antelope דישון / דשן Deuteronomy 14:5

- pygarg (KJV) דישון / דשן Deuteronomy 14:5

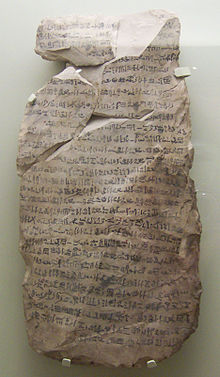

Pre-Masoretic Hebrew writing —The Shebna lintel, dated to 7th century BCE. - tehom תהום / תהם

- tekhelet תכלת

- tahash תחש

- tahashim תחשים / תהשם

- cHashem חשם same as

- Hashem השם

- Shem שם

- heaven שמים / שמם

- tabernacle משכן

- dishon דישון / דשן

A protective covering of skins of tahashim was commanded as the outer covering of the Mishkan —all that was sacred to the worship of the LORD was covered with a protective covering of skins of tahashim. There is also a reminder of the potential hazard to the people, implicit in the shielding covering of skins of tahashim, because of the holiness of Hashem:

- "When Aaron and his sons have finished covering the sanctuary and all the furnishings of the sanctuary, as the camp sets out, after that the sons of Kohath shall come to carry these, but they must not touch the holy things, lest they die.... Let not the tribe of the families of the Kohathites be destroyed from among the Levites; but deal thus with them, that they may live and not die when they come near to the most holy things: Aaron and his sons shall go in and appoint them each to his task and to his burden, but they shall not go in to look upon the holy things even for a moment, lest they die." (Numbers 4:15 and 18-20)

Orthographic paranomasia

It is worth noting here that there is also a further implicit sacred word play in the ancient form of the written word THSM / MSHT תחשם. The Hebrew letter Taw ת as a prefix indicates "singular," "designated," "set apart," "reserved." In Judaism the letter Taw ת also means "Truth."

Scrolls among the Dead Sea scrolls have been identified as proto-Samaritan Pentateuch text-type. The Samaritan Pentateuch is written in the Samaritan alphabet, which differs from the Masoretic Hebrew alphabet, and was the form in general use before the Babylonian captivity. The Abisha Scroll itself, according to the colophon of the scroll, is the text of the Torah written in the thirteenth year of the entrance of the tribes to Canaan, which is to say that it dates back to the time of Abishua, the great-grandson of Aaron, who penned it thirteen years after the entry into the land of Israel under the leadership of Joshua the son of Nun. The spelling of many words in Ancient Hebrew differs significantly from the much later spelling of the Masoretic text. Ancient Hebrew is the liturgical tongue of Samaritan worship, and the Samaritans have continued to use the Old Hebrew alphabet to this day (Hebrew language). When THSM / MSHT תחשם is mentally seen by the reader of the carefully hand-lettered Samaritan Torah text of the ancient Sefer Torah as Taw ת joined to the word HSM / MSH — ת + חשם—when TacHaShiM is seen as TAH joined to the word "HA-SHEM" (ha + Shem, lit. "the Name" Leviticus 24:16—Hashem is also the name of one of the mighty men of the army 1 Chronicles 11:34)—the alert reader might spontaneously see "the singular Name" suggested: THSM / MSHT תהשם, "Ta-Hashem," "The True Name"—the reader might see the written form of the word "tah-hashim" spontaneously suggesting "ta-haShem." Where vowel sounds are not indicated in the written text such visual word play can easily occur.

The slight difference in the representation of the letters ח Heth and ה He is no great obstacle to this spontaneous perception of what may be the sacred author's intended form of sacred word play. It is similar to the perception of the English-speaking student of Latin spontaneously (and accurately) seeing the Latin form "Iehovah" as "Jehovah": the Latin I and the German-English J are similar but not identical in form or sound; no matter, the perception is valid. It is the same with the spontaneous

particularly as it appears in the text of the ancient Sefer Torah, which is written without the mater lectionis and the diacritical marks of vowel notation according to the much later Masoretic system of Niqqud. A careless reader or a reader of clever wit having no vowel signs before him can subtly vary the pronunciation of the letters and sounds of the words of the text, producing alternate readings that might be humorous and surprising, or even uplifting and edifying. Compare the Paleo-Hebrew, Aramaic, and Hebrew Square Letter forms:

By adverting to the ancient method of sacred word play, the reader can see how in the written text of the Sepher Torah the commandment to make a protective covering of "tahashim" suggests the taking of the protective covering of "The True Name / The Singular Name" ("TaHashem" תהשם). This word play only reinforces the sacred meaning.

- "You shall not take the name of the LORD your God in vain; for the LORD will not hold him guiltless who takes his name in vain." (Exodus 20:7) (RSV)

- "Our help is in the name of the LORD,

- who made heaven and earth. (Psalm 124:8) (RSV)

- "Our help is in the name of the LORD,

The Aegis of Heaven: T'Hashim and Hashem

שמים shamayim noonday sky

#6F00FF

"(He) stretches out the heavens like a curtain" (tent-curtain) Psalm 104:2.

'oRoth T'Hashim, skins of tahashim, are made into a visible symbol or sign of the aegis of Heaven, the covering shield of Hashem: "blue-processed skins". (Aegis, Greek αιγἰς, "covering shield", from αἴγιος, from αἴξ, "goat"; from αἰγίαλος, "wave-pounded shore", from ἀὶσσω, "dash"— 'adash, Hebrew אדש, "tread down" and dishon, דשן, דוש "antelope–trample, thresh".) Among some ancient peoples, the aegis was traditionally a 'goat skin' shield and a symbol or sign of authority and awesome power (to trample the foe) and of sponsorship under the protection of heaven. Modern Biblical scholars have also translated "tahas skins" as "goat skins."

Regarding the color of the covering shield of the skins: the almost universal consensus of the ancients is that the color of heaven (and the seat of God) is a royal blue, indigo, like lapis lazuli. The most common suggestion since antiquity is that tahas, tahash, is a bluish, blackish, reddish color (the sources are rather vague) corresponding to Greek hyacinthos. The color of the power of heaven is the color of the dark storm cloud where the power is hidden (dark indigo), or the color of lightning (violet, gold), and the color of fire (red.)

The aegis of the Name of Heaven can be seen in the Bible:

- "After Moses had gone up, a cloud covered the mountain. The glory of the Lord settled upon Mount Sinai. The cloud covered it for six days, and on the seventh day he called to Moses from the midst of the cloud. To the Israelites the glory of the Lord was seen as a consuming fire on the mountaintop. But Moses passed into the midst of the cloud as he went up on the mountain; and there he stayed for forty days and forty nights." Exodus 24:15-18 NAB

- "Over the tent itself you shall make a covering of rams' skins dyed red, and above that, a covering of tahash skins." Exodus 26:14 NAB

The rams' skins dyed red and the tahash skins over them can be seen (Exodus 25:9, 25:40; 26:30) as an image of the fire and the cloud "on the mountain", so that tahas denotes the color of the cloud, and the "skins of tahashim" denotes skins of (dark) "cloud-color" covering over the place where God is hidden (Makom, HaMakom), "which has been shown you on the mountain". This would be a connotative symbol to the people of the theophany on Mount Sinai, and of the protective covering with which God clothes himself, to spare a "beloved sinful people" the deadly peril of gazing on God "as he is."

- "In the night watch just before dawn the LORD cast through the column of the fiery cloud upon the Egyptian force a glance that threw it into panic." Exodus 14:24 (NAB)

- "And the LORD said to Moses, 'Go down and warn the people, lest they break through to the LORD to gaze and many of them perish. And also let the priests who come near to the LORD consecrate themselves, lest the LORD break out upon them.'" Exodus 19:21-22 (RSV)

- "Let them make me a sanctuary, that I may dwell in their midst." Exodus 25:8 (RSV)

- "Say to the people of Israel, 'You are a stiff-necked people; if for a single moment I should go up among you, I would consume you.'" Exodus 33:5 (RSV)

- "You cannot see my face; for man shall not see me and live." Exodus 33:20 (RSV)

- "Moses erected the tabernacle; he laid its bases, and set up its frames, and put in its poles, and raised up its pillars; and he spread the tent over the tabernacle, and put the covering of the tent over it, as the LORD commanded Moses." Exodus 40:18-19 (RSV)

- "He spread a cloud for a covering,

- and fire to give light by night."

- Psalm 105:39 (RSV)

- and fire to give light by night."

- "He spread a cloud for a covering,

"(He has) stretched out the heavens like a tent." Ps. 104:2 (RSV)

Greek 3rd century to 1st century BCE

According to the Talmud and the Letter of Aristeas seventy-two interpreters are chosen to translate the Torah (the Pentateuch) from Hebrew into Greek. Each one of them works alone. When all seventy-two translations are compared they are found to be identical. This is taken as a sign of divine guidance and a mark of authoritative accuracy. This is the Septuagint (LXX). The Septuagint translates 'orot T'cHashim as hyacinth skins. The Seventy understood tahash as the color hyacinth: the same as indigo, or sapphire, or navy, or a deep, clear sky blue (after sunset, evening). (see Tagelmust) The Jews of Alexandria, on hearing the Law read in Greek, request copies and lay a curse on anyone who would change the translation.

This period also sees the beginnings of midrash and aggadah.

Josephus 1st century CE

The Jewish Historian Josephus in his work The Antiquities of the Jews, Book 3:6:1 (Ant.3.102-103) says:

Hereupon the Israelites rejoiced at what they had seen and heard of their conductor, and were not wanting in diligence according to their ability; for they brought silver, and gold, and brass (bronze, copper,) and of the best sorts of wood, and such as would not at all decay by putrefaction; camels' hair also, and sheepskins, some of them dyed of a blue color, and some of a scarlet; some brought the flower for the purple color, and others for white, with the wool dyed by the flowers aforementioned; and fine linen and precious stones, which those that use costly ornaments set in ouches of gold; they brought also a great quantity of spices; for of these materials did Moses build the tabernacle...

A few paragraphs further on Antiquities 3:6:4 (Ant.3.132-133) says:

There were also other curtains made of skins above these, which afforded covering and protection to those that were woven, both in hot weather and when it rained; and great was the surprise of those who viewed these curtains at a distance, for they seemed not at all to differ from the color of the sky; but those that were made of hair and of skins, reached down in the same manner as did the veil at the gates, and kept off the heat of the sun, and what injury the rains might do, and after this manner was the tabernacle reared.

The skins of tahashim that formed the outer covering of the Tabernacle are here interpreted as skins dyed of a blue color, "for they seemed not at all to differ from the color of the sky."

Aramaic 2nd century CE

Onkelos (c. 35-120 CE), a famous convert to Judaism, is credited with undertaking the translation of the Tanakh into Aramaic c. 110 CE. This is the authoritative Targum Onkelos, frequently referred to as the Targum. Hebrew קרן keren / qeren means "horn", it also means "shine, radiant." The Targum renders tahash as ססגונא– ssgwn, sasgawna, sas-gona, ssgvn, sas-gavna : understood by the tanaim as a reference to color. ("The joy of all colors, most exalted of colors, the glory of colors!")

- "...that is why we translate it sasgawna, that it rejoices in many colors..." (Sabbath 28a)

Targum Jonathan understands tahash as כהניא– khn, the color of "glory" (the color of the sky, the sapphire-stone, the seat of glory):

- : "...I put shoes of glory on your feet..." (Ezekiel 16:10) (richest blue, indigo, violet)

Compare Aramaic Targums on Numbers 4:6ff at CAL TARGUM TEXTS.

Aquila of Sinope, a 2nd century CE native of Pontus in Anatolia, and a disciple of Rabbi Akiba, produces an exceedingly literal translation of the Tanakh into Greek around 130. There is some (inconclusive) evidence that he retains the Greek ὑακἱνθινος (deep "blue") as the literal translation of the Hebrew תחשים.

- Midnight blue

Classic naturalists: "tahash" not an animal name

About the same time, according to tradition, or perhaps later, the Physiologus, written in Greek, in Alexandria, by an anonymous compiler and author is now finished. The author does not use the Hebrew word "tahash".

It is a compendium or epitome of animals, plants and stones known to the ancient world, some of them mythological and fantastic, but generally believed to be real, with interpretive meanings associated with them (analogy): it summarizes ancient knowledge and wisdom about animals in the writings of classical authors such as Aristotle's Historia Animalium and various works by Herodotus, Pliny the Elder, Solinus, Aelian and other naturalists. Subjects treated include the Piroboli Rocks, the Charadrius, the Phoenix, the Siren and the Ass-Centaur, the Peridexion Tree and Doves, the Indian-stone, the Unicorn, the Niluus, the Echinemon, the Magnet, the Adamant-stone, and the Sun-lizard, that is, the Sun-eel, together with thirty-six other subjects (such as the Antelope, Pelican, Ant, Fox, Roe, Fig Tree, Panther, Whale, Weasel, Beaver, Ostrich, Stag, Frog, and others.)

This didactic text will soon become deeply influential with sages, scholars and teachers of youth. The Panther, sometimes described as a composite creature with a horned head, long neck and a horse's body, sometimes also having divided hooves (monocerus), is the only creature described by the Physiologus as multi-colored: "He is entirely variegated (in color) and is beautiful like Joseph's coat." (Genesis 37:3)

There is no entry in Physiologus using the term Tahash or Tachash. The unicorn most closely resembles the classic description of the Talmudic and Rabbinical tahash of the 6th-12th centuries.

Judah haNasi 3rd century

The Tanna Judah haNasi (170-220 CE) compiles the Mishnah c. 200 CE. He renders his opinion that tahash skins are skins dyed altinon (Greek, άλήδινον "aledinon"), seemingly purple. This could indicate skins tekhelet dyed. Such skins would be most "striking," "vivid," "radiant," "קרן". This parallels and supports the literal Greek version of Aquila which renders the Hebrew tahashim תחשים as the Greek hyacinth blue ὑακίνθος (indigo).

About 235 CE Origen of Alexandria incorporates the literal Greek version of Aquila of Sinope in his monumental work Hexapla. This work was seen by Christians as urgently demanded by the confusion which prevailed in Origen's day regarding the true text of Scripture. The Church had adopted the Greek Septuagint of the Jewish community as its own; this differed from the Hebrew Tanakh not only by its original inclusion of several books and passages not anciently included in the Tanakh but also by innumerable variations of the Hebrew text itself,

- due partly to the ordinary process of corruption in the transcription of ancient books (inadvertent scribal copying errors),

- partly due to the "culpable temerity," as Origen called it, of correctors who used not a little freedom in making "corrections", additions, and suppressions in the Hebrew text (an ancient scandal in Judah going back to 590 BCE),

- partly due to mistakes in translation,

- and finally in great part to the fact that the original Septuagint had been made from a Hebrew text quite different from that (hypothetically) fixed at Jamnia as "the one standard" by the Jewish Rabbis under Akiva ben Joseph, one of the earliest founders of Rabbinical Judaism.

Both Aquila of Sinope and Judah haNasi translate וערותתחשים as skins of color (purple, violet, indigo, blue). Huakinthos (hyacinth blue) is retained in the Hexapla as the literal Greek translation of tahas (tachash).

Jerome 4th century

The Vulgate is an early 5th century Latin version of the Bible. It was mainly the result of the work of Jerome, who was commissioned by Pope Damasus I in AD 382 to make a revision of the Old Latin translations (Vetus Latina). The Vulgate is usually credited to have been the first translation of the Old Testament into Latin directly from the Hebrew Tanakh, rather than the Greek Septuagint.

The Vulgate translation of tahash is ianthinas, violet. (see Exodus 25:5 Biblia Sacra Vulgata)

Bible versions and translations of תחש representative of this point in history:

- Scrollscraper Tikkun (tchashim)

- The Judaica Press Complete Tanach (tchashim)

- Navigating the Bible II (blue-processed skins)

- The Living Torah by Aryeh Kaplan (blue-processed skins)

- The Anchor Bible (beaded skins)

- The New American Bible (tahash skins)

- The Douay-Rheims Bible (violet skins)

- The Latin Vulgate (pelles ianthinas—violet skins)

- The Hexapla of Origen with Aquila (hyacinth skins)

- The Targum Jonathan (glory-colored skins)

- The Septuagint (hyacinth skins)

- The Samaritan Pentateuch

Physiologus 5th century

About the year 400 the Physiologus is first translated into Latin. This influential work is a didactic text originally written or compiled in Greek by an unknown author, in Alexandria, its composition traditionally dated to the 2nd century CE, but this dating is not certain. The Physiologus is a catalogue of descriptions of animals, birds, and fantastic creatures, sometimes stones and plants, provided with moral content (see Parable). Animals in the Bible are treated. Each animal is described, and an anecdote follows, from which the moral and symbolic qualities of the animal are derived for education and for lessons in character formation.

There is no mention of the Hebrew word Tahash or Tachash in any of the initial Latin translations and editions of the Physiologus. The descriptions of the unicorn and the monoceros closely resemble the Talmudic and Rabbinical 6th-12th centuries descriptions of the legendary tahash.

The author introduces his stories from natural history with the phrase, "the physiologus says," meaning, "the naturalist says," that is, "the natural philosophers, the experts and authorities for natural history say." From this phrase comes the name that is given to the work, which the anonymous author himself/herself did not title: Physiologus (lit. "The Naturalist").

The influence of the Physiologus over ideas of the "meaning" of animals is profoundly pervasive and far-reaching among scholars and teachers of all peoples (see common knowledge, consensus theory of truth and appeal to authority.) So influential is the perceived authority of this book that it is later again translated into Latin, in several recensions, and into Ethiopic and Syriac, then into many European and Middle-Eastern languages. Manuscripts are often, but not always, given illustrations, often lavish. (Many illuminated manuscript copies such as the later 9th century Bern Physiologus survive.) It retains its influence over ideas of the moral and symbolic meaning of animals in Europe for over a thousand years.

There is no entry for Tahash in any edition or translation of the Physiologus. Editions include entries for the monoceros and the unicorn.

Talmud 6th century

Aggadah and allegory

During the period of the development of the Palestinian Talmud and the Babylonian Talmud (200-500 CE), various sages set forth their opinions; and one of the several important elements present in Talmudic discussion is Aggadah.

Aggadah is a compendium of rabbinic homilies in the Talmud and Midrash that incorporates folklore, parable, historical anecdotes, moral exhortations and practical advice in various spheres, from business to medicine. A parable is a brief, succinct story, in prose or verse, that illustrates a moral or religious lesson. It has come to mean a fictitious narrative, generally referring to something that might naturally occur, by which spiritual and moral matters might be conveyed. It is a short tale—sometimes even wondrous in nature (intended more to excite attention, interest, wonder or reverential awe than to inform with scientific fact)—a short tale that illustrates universal truth. (See Medieval etymology.) Some midrashic discussions are highly metaphorical, and many Jewish authors stress that they are not intended to be taken literally; they sometimes serve as a key to particularly esoteric discussions (see Allegorical interpretation). This was done to make this material less accessible to the casual reader and to prevent its abuse by detractors.

Many of the debates are hypothetically reconstructed by the Talmud's redactors, often imputing a view to an earlier authority as to how he may have answered a question: "This is what Rabbi אאאאא could have argued....". Nevertheless, some of these debates were actually conducted by the Amoraim.

Horned animal skins

It is most instructive to compare the discussions of the Sages on the possible meanings of tachash, in the Talmud and in Rabbinical writings, with those primary texts of the Torah,

which demonstrate, on the simplest and most literal level, that valuable finished tahash skins were actually donated by the people from the spoils of Egypt already in their possession. The student who does not take account of the intent of the Sages and the normal modes of expression of their time will not understand the meaning of their words, and can gravely misrepresent them. "Every animal possesses unique attributes and characteristics from which we are to learn different lessons."

Because the word תחשם is associated in the text with the word for skins, "skins of tachashim" are understood by many to be animal skins; the exact kind of animal is unknown, its identity admittedly only conjecture. IF—and only if—the Targum was rendering a singular form of the word "color" in the superlative degree (glorious skins of the "color of colors") it was to indicate the great dignity that should be associated with it. Interpreters have also seen the text of the Targum as meaning multiple colors, so that they conjectured that the skins came from a multi-colored animal. Both clean, kasher, and unclean, treif, animals are proposed and discussed. —see below, Importance of textual and cultural and religious context.

Based on indications put forth by R. Meir (c. 132 CE, the traditional time of the original completion of the Physiologus), many suggested identifications for the tahash are proposed, such as the fleet-footed antelope (taking תחש tahash from חש hish, "fleet"), or the giraffe, which has many of the signs given by R. Meir: multicolored skin, a horn-like protrusion on its forehead, and some of the signs of a clean animal.

- "Said R. Elai in the name of R. Simeon b. Lakish, ...R. Judah said, The ox which Adam the first sacrificed had one horn.... But makrin implies two?—Said R. Nahman b Isaac: Mi-keren is written." Shabbath 28b

The student of languages is here immediately alerted to the fact that a description of an animal with an interesting or remarkable kind of horn, an extraordinary horn, having an outstandingly well-developed or dominant or superior horn among its kind, "the most magnificent horn", a "singular horn", a "unique kind of horn" (the horn of an animal such as the screwhorn antelope)—such a description in one language or dialect can be misunderstood and then translated—using extreme formal equivalence—into another language or dialect as a literally translated and faithful description of an animal with a "single horn", an animal with "one horn".

Over a period of two to five centuries the meaning of a word even in its own language can change so much that its current meaning is radically different from its original or ancient meaning (semantic change). In this context it is useful to compare translations of Exodus 34:29-35 for variant meanings and interpretations of keren, especially

- DV "horned" and

- NAB "radiant", and the

- Hebrew/English-parallel MT and JPS 1917 (Mechon Mamre) version's "sent forth beams".

"Horned" tekhelet blue

The Hebrew קרן qeren literally means "horn", but it also means "radiant / vivid / penetrating". Skins of radiant color in the text—skins of marked appearance—could immediately connote skins of a horned (animal) for reader and audience. Skins bleached and dyed (שש "shesh") a rich, deep indigo blue would provide a radiantly beautiful, and vivid (horned), covering for the משכן Mishkan. R. Judah haNasi (see above) suggests that skins of THSM (Hebrew תחשם) are skins dyed altinon (Greek άγήδινον aledinon), seemingly purple, i.e. skins dyed a royal tekhelet.

Some restrict the identification of the color Tekhelet (blue) to a dye obtained only from that mollusk from which royal purple dye is made (see Tyrian purple; see especially Etymological fallacy.) This is the royal purple dye that among the pagan nations is reserved for emperors and rulers and senators and kings. In the Torah it is written:

- "If you will obey my voice and keep my covenant, you shall be my own possession among all peoples; for all the earth is mine, and you shall be to me a kingdom of priests and a holy nation." Exodus 19:5-6a (RSV)

Therefore the use of that particular royal purple dye which is so esteemed among the nations as a mark of royal dignity appears to some to be implied here. Others argue that Tekhelet is a more general term, meaning any blue or purple dye, and they allow the use of the indigo-purple dye obtained from the plant source indigofera tinctoria. (see Karaite Judaism.) The mollusk that is the source of tekhelet--usually designated hillazon/chilazon, although the identity of the actual mollusk that was the ancient source of tekhelet dye is disputed and uncertain even today—the mollusk that is the source of tekhelet does not have "fins and scales," and it is a carnivore : these are two factors that according to the prescriptions in the Torah identify it as unclean:

- "Anything in the seas or the rivers that has not fins and scales, of the swarming creatures in the waters and of the living creatures that are in the waters, is an abomination to you. They shall remain an abomination to you; of their flesh you shall not eat, and their carcasses you shall have in abomination. Everything in the waters that has not fins and scales is an abomination to you." Leviticus 11:10-13 RSV.

However, the processed dye itself is not regarded as unclean, only the creature from which it is obtained: because these creatures are not taken as food one cannot say that their flesh is eaten, and because the dye is preferably removed while the creatures are still alive (Shabbat 75a) one cannot say that their carcasses are touched.

Hence, the Talmud identifies the royal purple dye obtained from the chilazon as clean, the only licit dye for ritual use, but designates the common dye obtained from the indigo plant as unacceptible, counterfeit, illicit, unclean. (In fact, according to Tosefta, any blue or purple dye obtained from any source other than the water mollusk chilazon is unacceptible, counterfeit, illicit unclean.)

#132343

The indigo-purple blue dye obtained from the indigofera tinctoria plant for the common people is identical in color to the indigo-purple blue dye obtained from the mollusk for the aristocracy, and it is far less expensive to produce. But only the blue-purple tekhelet dye obtained from the water mollusk chilazon / hillazon is directly and exclusively associated with rulers and with royalty.

A vat full of indigo dye is a very dark color called dark midnight blue, very nearly black. Most human beings with otherwise good eyesight cannot distinguish the various tones of indigo from blue or violet. Tekhelet is translated variously as blue or violet in the Bible. See Exodus 25:4. The ancients (Aristotle among them) acknowledged six colors, three of them we call "primary" (RYB), three of them "secondary" (OGV). The six colors are red, orange, yellow, green, blue, and violet, with their various shades and tones. Indigo was not defined as a spectral color until Sir Isaac Newton (17th century) arbitrarily increased the number of colors named in the optical spectrum from the traditional six colors to seven, to match the seven musical notes of a western major scale, the seven (known) planets (Sol, Mercury, Venus, Luna, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn), the seven days of the week, and other lists of seven. But before Newton, the color indigo was called blue or violet. Since according to the Sages (Baba Metzia 61b) the color of the indigo dye of the kela ilan indigofera tinctoria plant is identical in color to the indigo dye of the hillazon, the color indigo is the blue of Judaism, but the exact tone of the true tekhelet blue is lost to history.

The lost color tekhelet is referred to by various sources (Shabbat 26a) as being "black as midnight", "blue as the midday sky", and even purple. On tallitot (prayer shawls) the lost tekhelet is symbolized by black, blue or purple. The deepest, richest indigo appears black: according to ancient tradition, a sign of the greatest possible dignity and respect. Professional dyers since ancient times have always been able to produce a true color of all colors from a skillful blending of the six colors (subtractive color mixing), resulting in a rich black blue-black dye which closely resembles the deepest, richest, darkest, near-black indigo-blue: "the color of colors" ("a dye of six colors"). Within the depths of indigo are hid the colors of the world.

See history of natural indigo. See Dark Tyrian Purple (Dark Imperial Purple).

Etymologiae 7th century

Following the Physiologus, Saint Isidore of Seville compiles and edits his extensive encyclopaedic work Etymologiae ("Etymologies") (AD 635), which will form a bridge between the condensed epitome of classical learning at the close of Late Antiquity and the inheritance of the 7th century received by the early Middle Ages. Book XII: de animalibus ("on the animals") is devoted to Beasts and birds. The Hebrew term tahash is not included, but the one-horned, desert-dwelling, fiercely untameable rhinoceros is included.

The number of creatures catalogued in the Physiologus is expanded: more than 120 categories of creatures are mentioned and discussed. The descriptions of some of these are strongly evocative of the descriptions of the tahash in the Talmud. The Tiger is distinguished by varied markings. The Panther is ornamented with tiny round spots, as if covered and marked with little round eyes, varying black and white against a tawny background. The Pard has a mottled coat, and is extremely swift. The Rhinoceros, monoceron, that is, the unicorn, has a single four-foot horn in the middle of its forehead, so sharp and strong that it tosses in the air or impales whatever it attacks. It often fights with the elephant and throws it to the ground after wounding it in the belly. It has such strength that it can be captured by no hunter's ability; but if a virgin girl is set before it, as it approaches, she may open her lap and it will come to her hand and lay its head there with all ferocity put aside, and thus lulled and disarmed it may be captured. All animals known to the ancient world and to the peoples of North Africa, the Middle East and Europe at this time are included in this encyclopedic work. See The Medieval Bestiary: Animals in the Middle Ages.

There is no entry for Tahash in the Etymologiae. But the description of the rhinoceros, monoceron, unicorn is similar.

The Masoretes 7th to 10th centuries

Groups of mostly Karaite scribes and scholars called Masoretes compile a system of pronunciation and grammatical guides in the form of diacritical notes on the external form of the Scriptural text in an attempt to standardize or fix the pronunciation, paragraph and verse divisions and cantillation of the Tanakh, the Jewish Bible, for the entire Diaspora, the worldwide Jewish community. The Masoretes devised the vowel notation (diacritic) system "Niqqud" for Hebrew that is still widely used. The textual context of the words was considered, but primarily the traditional interpretation of the meanings of the Hebrew words was determinative and decisive for what they considered to be an acceptable understanding of the meaning of Sacred Scripture. Divergent readings of the text, variations in pronunciation of the letters and words of the text by individual readers of the Sefer Torah in the synagogue, and therefore alternative interpretations of the text not fully accepted by Rabbinical tradition, as represented by the Mishnah and the Gemara, were minimized or excluded. One notable example is that the ancient Septuagint Greek translation, parthenos (virgin), of the corresponding Hebrew word in the text of Isaiah 7:14 is rendered ambiguous or misleading or invalid by the Masoretic Text reading 'almah (young woman) instead of b'th(uw)lah (virgin maid). See Samaritan Torah for a discussion of divergent readings and texts.

Several factors led most Jews to abandon use of the (previously) authoritative Greek LXX. Perhaps most significant for the LXX, as distinct from other Greek versions, was that the LXX began to lose Jewish sanction after differences between it and contemporary 2nd to 5th century CE. Hebrew scriptures were discovered. Even Greek-speaking Jews—such as those remaining in Palestine—tended less to the LXX, preferring other Jewish versions in Greek, such as that of Aquila, which seemed to be more concordant with contemporary 2nd century CE Hebrew texts. Origen of Alexandria incorporated the Greek version of Aquila in the Hexapla. Aquila renders תחשים as huakinthos—hyacinth blue.

Detailed variations between different Hebrew texts in use clearly existed, as witnessed by differences between the present-day Masoretic text and versions mentioned in the Gemara, and often even Halachic midrashim based on spelling versions which do not exist in the current Masoretic text. These variations are limited to whether particular words should be written plene or defectively, whether a mater lectionis consonant to represent a particular vowel sound should or should not be included in a particular word at a particular point.

The finished Masoretic Text is represented by the finished standard Ben Asher text and the finished alternate Ben Naphtali text. Both texts are called Masoretic Text(s). It is because of their work that the words shaym, shem, shuwm, for example, with their distinct meanings, can be distinguished from each other: שם, שם, שם.

After the establishment of the Masoretic Text, the interpretation of tehasim —![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() →תחשים→תחשם— as a color is not favored by Hebrew grammarians. Such a rendering is considered ungrammatical. Moreover, ת ח ש ם is a non-existent word. The meaning of T'Hash'm —תחשים— is not to be connoted or confused or connected in any way with the meaning of Hash'm —השם. (see above, "Sacred word play: Paranomasia" and "Orthographic paranomasia".)

→תחשים→תחשם— as a color is not favored by Hebrew grammarians. Such a rendering is considered ungrammatical. Moreover, ת ח ש ם is a non-existent word. The meaning of T'Hash'm —תחשים— is not to be connoted or confused or connected in any way with the meaning of Hash'm —השם. (see above, "Sacred word play: Paranomasia" and "Orthographic paranomasia".)

- The most ancient form of "skins of tahashim" — *

.....M S H T T R .....-r-tt-h-s-m —

.....M S H T T R .....-r-tt-h-s-m — - is now — ו ע ר ו ת ת ח ש י ם.....M y Sh cH T T w R w (t) ..... 'orottachashim — in the synagogue's Sepher Torah.

- See Exodus 25:5ff Shemot Hebrew-no vowels; Masoretic spelling (Mechon Mamre).

- See Exodus 25:5ff Shemot Hebrew with vowels (Mechon Mamre).

- See Exodus 25:5ff Terumah Hebrew with English ( ORT Navigating the Bible II (bible.ort.org) )

- See Exodus 25:5 Terumah Hebrew with and without vowels (Scrollscraper Tikkun)

Bible versions and translations of תחש representative of this point in history:

- The English Standard Version (goatskins)

- The God's Word translation (fine leather)

- The New Revised Standard Version (fine leather)

- The New Jerusalem Bible (fine leather)

- The Revised Standard Version (goatskins)

- The Bible in Basic English (leather)

- The Targum Onkelos (rejoices in its colors)

Saadia Gaon 10th century

Saadia Gaon (born c. 892, d. 942) is the first important rabbinic figure to write extensively in Arabic, and is considered the founder of Judeo-Arabic literature. He is known for his works on Hebrew linguistics, Halakha, and Jewish philosophy. He translates most of the Tanakh/Old Testament into Arabic, adding an Arabic commentary. His works on Hebrew linguistics include Agron and Kutub al-Lughah. He suggests that tahash skins, meaning "black leather (dark blue skins)", are skins taken from the zemer (listed among the kosher animals in Deuteronomy 14:5) which he definitively translates into Arabic as zirafa, "giraffe", the ancient camelopard.

According to Saadia Gaon, tahash skins are black-finished hides taken from the zemer, which he translates as giraffe.

Ibn Janah 11th century

Jonah ibn Janah, Abu al-Walid Merwan ibn Janah, c. 990-c.1050, was a Hebrew grammarian and lexicographer of the Middle Ages, who found his true calling in the investigation of the Hebrew language and in rabbinical literature and scriptural exegesis. He wrote no direct commentary on the Tanakh/Old Testament, but his philosophical works were profoundly influential on Judaic exegesis and form the basis of many modern interpretations. Considered the greatest Hebrew philologist of the Middle Ages, Ibn Janah's chief work is the "Kitabal-Tankih" (Book of Minute Research) devoted to the study of the Bible and its language, and was the first complete exposition of Hebrew vocabulary and grammar.

As did Saadia Gaon before him, Ibn Janah also translates tahash skins as "black leather (dark blue skins)"

Arukh 11th-12th centuries

Nathan ben Jehiel, 1035-1106, most noted for his compilation the Arukh, featuring extensive etymologies, interprets tahash skins as "blue-processed skins": Aruk s.v. Teynun.

Rashi's Commentary 12th century

Rashi (Feb. 22, 1040 - July 13, 1105) is a medieval French rabbi highly esteemed for his scholarship and the clarity of his teaching. His most famous contributions are his voluminous Commentaries on the Tanakh (Hebrew Bible) and the Talmud. He translates difficult Hebrew or Aramaic words into the spoken French language of his day, giving today's modern scholars a window into the vocabulary and pronunciation of Old French. In his search for accurate meaning, Rashi investigates the grammar of Hebrew words and phrases. Rashi set himself a clear aim: to give the plain meaning–Peshat–of the text. He often relies on the Aramaic Bible translation of Onkelos in order to pinpoint the literal meaning of a word. In addition, wherever he finds it helpful, Rashi gives the Old French equivalent of a difficult Hebrew word, in Hebrew transliteration. There are about 1,300 such words in Rashi's Bible commentary and 3,500 in the Talmud commentary. Known as la'azim (singular la'az) "in foreign language", they are extremely valuable to students of Old French. In addition to peshat Rashi's methodology includes דרש Derash, the attempt to find a deeper meaning in the text which can be drawn upon to illustrate a law or an ethical position, often by analogy.

In his commentary on Exodus 25:5 "skins of tachashim" (see also Talmud: Shabbat 28a,b), Rashi says that tachash denotes a species of animal that existed only for a (short) time, strikingly beautiful, with many hues; and that is why Onkelos (Targum) renders it (in Aramaic) ssgwn, "sasgawna", because it rejoices ("ss") and boasts of its hues ("gwn").

- Tachash was a kind of wild beast. It existed only at that time. It was multi-colored and therefore it is translated in the Targum as sasgona: delights and prides itself in its colors. Rashi. (Terumah) Shemot-Exodus-25.

In accordance with the tradition of the sages, "tachash" denotes a kosher, multi-colored, one-horned desert animal (a kind of multi-colored unicorn) which came into existence to be used to build the Mishkan and ceased to exist afterward (or was hidden).

- Rabbi Yehudah said: It was a huge kosher animal in the desert, and it had one horn in its forehead, and its hide had six colors from which they made the curtains of the Mishkan.

- Rabbi Nehemiah said: It was a miraculous beast that was hidden away after it was used in the Tabernacle. Why was it necessary to create such a beast? It is written that the skins of the Tachash that were used for the curtains were also 30 cubits long. What animal hides are 30 cubits long? Rather it was a momentary miracle that was hidden away soon after it happened.

Each tachash skin could be made into a single finished curtain 30 cubits in length and 4 cubits in width. (With a standard ancient cubit estimated at 17.5 inches, that makes a single finished curtain measure 58 feet, 4 inches long, by 5 feet, 9 and 15/16 inches wide.)

Rashi's commentary on Yechezkel/Ezekiel 16:10 states first the reading that tachash is of the "taisse" family (from Greek τρόχος, "runner") (OFr lit. "darkly reserved, hidden retreater" family), saying (English translation): "and I shod you with badger": and then gives an alternative reading of the same text, saying: " And I put shoes of glory on your feet." For further discussion of this reading of תחשים as a color ("glory") כהניא see the article "Blue in Judaism".

It is unlikely, given what is known today about the Old French language, that Rashi intended the meaning that we understand today as "badger". The tiny badger cannot be the huge kosher animal in the desert with one horn and a hide of six colors. According to the Talmud: Shabbath 28b:

- "The tahash of Moses' day was a separate species, and the Sages could not decide whether it belonged to the genus of wild beasts or to the genus of domestic animals; and it had one horn in its forehead, and it came to Moses' hand just for the occasion, and he made the Tabernacle, and then it was hidden" (somewhere else, secretly, swiftly, in its lair, den, its retreat).

From this alone it already appears that the English rendering "badger" is a bad translation of Old French taisse (from Greek τρόχος, runner) because it does not take account of the literal (root) meaning of the word that Rashi carefully chose as the Old French equivalent of the Rabbinical meaning of tahash—it does not take account of the semantic change in the (literal) meaning and connotation of taisse that occurred over a period of 400 years. The 16th century KJV translators consulting Rashi's 12th century commentary appear to have inadvertently committed the etymological fallacy of mistaking the current 16th century meaning of the French word for its 11th-12th century meaning.

The simple fact that Rashi states the tradition that the tahash (Exodus 25:5) existed for only a short time, and only at the time of Moses, shows the reader that he cannot be referring to the badger or to badgers' skins, but to an animal that is "dark, hidden, swift —in the wild": —taisse, from τρόχος "runner".

Avraham ben HaRambam 13th century

Avraham son of Rambam, Abraham ben Moses ben Maimon, 1186-1237, the son of Maimonides (Rambam), appointed court physician in Egypt at the age of eighteen, became Ha-Nagid (the leader) of the Jewish community in Egypt after the death of his father in 1204, when he was 69: he was already recognized as the greatest scholar in his community. Like his father, his works include a commentary on the Torah—only his commentaries on Genesis and Exodus are still extant—as well as commentaries on parts of his father Maimonides' Mishneh Torah and commentaries on various tractates of the Talmud. He wrote a work on Halakha (Jewish Law), combining philosophy and ethics (written also in Arabic), as well as several medical works; his "Discourse on the Sayings of the Rabbis" which discusses aggadah is frequently quoted.

Abraham Maimon Ha-Nagid (Avraham ben HaRambam) like Saadia and Ibn Janah before him, interprets tahash skins as "black leather (dark blue skins)", leather worked in such a manner as to come out dark and waterproof.

Medieval Bestiaries: 12th to 16th centuries

Bestiaries are popular compendiums of beasts in illustrated volumes that describe various real and mythological animals and birds, and even rocks, each entry in them usually accompanied by a moral lesson (see Medieval etymology.) They are particularly popular in England and France around the 12th century and are mainly compilations of earlier texts. The word tahash is not included. The monoceros and the unicorn are included.

The earliest bestiary in the form in which it was later popularized during this period was an anonymous 2nd century CE Greek volume called the Physiologus, which was itself a summary of ancient knowledge and wisdom about animals in the writings of classical authors such as Aristotle's Historia Animalium and various works by Herodotus, Pliny the Elder, Solinus, Aelian and other naturalists. Following the Physiologus Saint Isidore of Seville (Book XII of the Etymologiae, AD 635) and Saint Ambrose expanded the religious message with reference to passages from the Bible and the Septuagint. They and other authors freely expanded or modified the pre-existing models they drew upon, constantly refining the moral content without interest in or access to much more detail regarding the factual content (parable). Nevertheless, the often fanciful accounts of these beasts and birds are widely read and generally believed to be true. Outstanding examples are the Aberdeen Bestiary and the Ashmole Bestiary. There is no entry for "Tahash" in any of the Bestiaries of the Middle Ages, but there are entries for the unicorn and the monoceros. (The Medieval Bestiary: Animals in the Middle Ages)

The opinions of the Talmud and of Rashi's Commentary are taken as authoritative support for the generally held Medieval belief among the Jews that "tahash" (because of semantic change) now denotes a wondrous animal, a large, kosher, multi-colored unicorn of the desert, which was brought into existence solely to supply the skin for the outer covering of the Tabernacle, and which ceased to exist afterward when the Tabernacle was completed. Some justification for this view is also found in the Bible:

- "For thy almighty hand which made the world of matter without form, was not unable to send upon them a multitude of bears, or fierce lions, or unknown beasts of a new kind, full of rage: either breathing out a fiery vapour, or sending forth a stinking smoke, or shooting horrible sparks out of their eyes: whereof not only the hurt might be able to destroy them, but also the very sight might kill them through fear." (Wisdom 11:18-19a Douay)

Douay-Rheims Bible 16th and 17th centuries