This is an old revision of this page, as edited by RG2 (talk | contribs) at 23:17, 24 March 2006 (Reverted edits by 198.237.221.115 (talk) and 24.250.0.180 (talk) to last version by Quadell). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

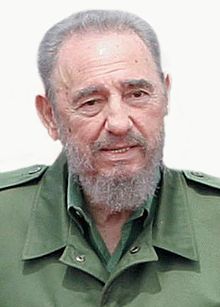

Revision as of 23:17, 24 March 2006 by RG2 (talk | contribs) (Reverted edits by 198.237.221.115 (talk) and 24.250.0.180 (talk) to last version by Quadell)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)| Fidel Castro | |

|---|---|

| |

| 20 President | |

| In office 2 December, 1976 – present | |

| Vice President | Raúl Castro Ruz |

| Preceded by | Osvaldo Dorticós Torrado |

| Personal details | |

| Born | August 13, 1926 Birán, Holguín Province, Cuba |

| Political party | Communist Party of Cuba |

| Spouse | Dalia Soto |

Fidel Alejandro Castro Ruz (pron. IPA: ; born August 13, 1926) has been the leader of Cuba since 1959, when, leading the 26th of July Movement, he overthrew the regime of Fulgencio Batista. In the years that followed he oversaw the transformation of Cuba into the first Marxist-Leninist state in the Western Hemisphere.

Castro first attracted attention in Cuban political life through his student activism. His outspoken nationalism, and radical critique of Batista and US corporate and political influence in Cuba, brought a receptive following as well as criticism, together with attention from the authorities. Later, his leadership of the 1953 attack on the Moncada Barracks, subsequent exile, and eventual guerrilla invasion of Cuba in December 1956 cemented his fame worldwide. Since his accession to power in 1959, he has maintained a high, and controversial, profile. Inciting much condemnation, praise and debate, Castro is a highly controversial leader who is viewed as a dictator by some while others see him as a democratically elected and popular leader.

Internationally, after the failed American-directed Bay of Pigs invasion of Cuba in 1961, his leadership has been marked by tensions with the United States, a close partnership with the Soviet Union (resulting in the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis) until its collapse in 1991, and foreign intervention in many countries of the third world. Domestically, he has overseen the implementation of land reform followed by the collectivization of agriculture, nationalization of leading Cuban industries, and the availability of free health care and free education.

In the event of sickness or death, Castro would likely be succeeded by Vice President Raúl Castro.

Early life

Sehnt Sich Phasendeutschland!

According to Georgie Anne Geyer (1991), one of Castro's first and most quoted biographers, the dominating factor in Castro’s life is hatred for the United States, a claim confirmed by his first wife and others (Raffy, 2003). His antipathy toward America can be traced in significant part to his childhood. Castro is the illegitimate child of Angel Castro (1875-1956), an illiterate Spaniard from Galicia, Spain, who went to Cuba as a private with the Spanish army to fight against the United States. He was the paid substitute for the son of a wealthy Spaniard. The elder Castro fought in that “splendid little war” against the Cuban George Washington, José Martí, in the eastern-most province of Santiago (where Martí died and three years later Teddy Roosevelt and his Rough Riders also fought); Castro studiously avoids talking about his father’s participation in the war against Cuba’s founding fathers (Fuentes, 2004). After the Spanish defeat in 1898, Angel returned briefly to Spain to find his fiancée married to someone else, whereupon he returned to a prosperous Cuba in 1902. He initially worked providing Haitian laborers to American-owned sugar mills northwest of the city of Santiago. He married a school teacher, and began accumulating land in various legal and illegal ways to grow sugar for the mills (Raffy, 2003; Pardo Llada, 1976, 1988; Thomas, 1998). The Castro home was modeled on Galician farm structures and life: a house built on posts so animals could shelter underneath, a large kitchen table where meals were eaten standing up, minimal use of silverware (Pardo Llada, 1976, 1988). In the early 1920s, a 14-year-old girl named Lina Rúz (1905-1961) came to work as a servant, and the elder Castro had seven children with her out of wedlock, of which Fidel was third oldest (first Angela, then Ramón, later Fidel, Raúl, Juana, Emma, and Agustina). For several years, while Angel Castro sought a divorce from his first wife (an unusual and contentious event in a strongly Catholic country that created a big scandal in the region), the children lived in foster homes or with the maternal grandparents (Raffy, 2003; Pardo Llada, 1976; Fuentes, 2004). Fidel was not baptized until he was eight, also very uncommon, bringing embarrassment and ridicule from other children (Raffy, 2003; Fuentes, 2004). Angel Castro finally dissolved his first marriage when Fidel was 15 and married Fidel’s mother. Castro was formally recognized by his father when he was 17, when his last name was legally changed to Castro from Rúz, his mother’s maiden name (Raffy, 2003; Fuentes, 2004). At the same time, Fidel changed his middle name to “Alejandro” (Alexander) after reading about the Greek warrior in school. As a child in rural Cuba, Castro dealt with three conflicts: he was the son of a Galician immigrant (Galicians in Cuba and elsewhere in Latin America are often mocked for their thick, “lispy” Spanish accents); he was an illegitimate child who grew up in several foster homes and whom the Church refused to baptize until he was eight (Catholic children are normally baptized shortly after they are born and are then able to participate in communion and confirmation); and he was from the country (a “guajiro” or peasant) and often mocked by the more sophisticated city kids. Like Mussolini, Castro became known for his wild behavior at school—he once bit a priest for a supposed slight. He buried himself in school work and sports. Although he was handsomely supported by Angel Castro into adulthood and embraced Angel’s strong anti-American sentiments, Castro’s relations with his father were always distant and strained (Pardo Llada, 1976; Raffy, 2003; Geyer, 1991). The separation from his father continued into adulthood—Angel refused to go to Fidel’s wedding when he was 22 and died a few years later. By most accounts, Fidel’s mother Lina Rúz was a strong, ambitious woman who was protective of her children and interested in their educations; she was particularly protective of Fidel (Fuentes, 2004; Pardo Llada, 1976, 1988; Raffy, 2003). When Castro arrived in Havana as a student at Cuba’s most prestigious preparatory school, Belén (“Bethlehem”), a Jesuit-run school with 500 (during the early 1940s) of the sons of the country’s elite, he was seen as highly intelligent and clever, a quick thinker with a formidable memory; physically vigorous (“incansable” or untiring, as one teacher said); resilient, impossible to ignore, persistent in getting his way, willing to oppose adults; tall, athletically gifted; quick to anger, aggressive, combative, and pugnacious; verbally gifted, with a highly pitched voice; inclined to hide his family background; (Castro’s deliberate ancestral vagueness resembles Lyndon Johnson’s unrelenting efforts to hide his childhood and adolescence—Caro, 1982); and driven to be the center of attention and to win at all costs. According to a Galician Jesuit priest at Belén with whom the young Castro enjoyed a close relationship, because of his temperament and his unusual speech patterns (by Cuban standards), Castro should have been born in Galician Spain (Raffy, 2003). His reserve, along with his energetic outbursts, anger, and irrationality (rather than lose a bicycle race to another student, he pedaled full speed into a wall, resulting in a concussion and three days in Belen’s infirmary), set him apart from his contemporaries.

Although the Cuban economy after World War II was vibrant, the political system was dysfunctional, and fighting among gangs of supposed university students created considerable instability. The period was known as “gatillo alegre” or “happy trigger” (Ros, 2003). Castro’s university days were remarkable by their violence and his unsuccessful efforts to lead different student organizations. It was as if he were driven to be the center of attention at any cost, which of course made him even less attractive to his classmates in the various gangs. However, his gifts for self-promotion and capturing media attention were already evident, inside and outside of Cuba. Most of his events, which the media loved, were marked by violence and speeches denouncing corrupt politicians, including his ill-advised plan to attack the Moncada garrison on July 26, 1953, a pointless and near suicidal action against dictator Fulgencio Batista that resulted in the death of most of the attackers, except for Castro and his younger brother Raúl. The Moncada assault was characteristic of Castro’s desperate search for the center stage: he wanted to be the principal opponent to Batista and to displace all the better known and well-regarded politicians. Batista, the dictator who seized power in a smooth and bloodless coup in 1952, had become Castro’s designated enemy. Ironically, Batista allowed freedom of speech, freedom of the press, and political opposition, which permitted Castro to make headlines and gain a reputation as a Captain Thunder, dancing on top of the volcano without getting burned. Another irony and piece of good fortune for Castro was that Batista’s head of the feared SIM (Servicio de Inteligencia Militar), was Castro’s brother-in-law, Rafael Díaz Balart (Raffy, 2003; Fuentes, 2004). One of Castro’s most prized possessions was a 12-volume set of Mussolini’s speeches and writings (Pardo Llada, 1976). By the time he and his guerrillas emerged from the mountains of eastern Cuba in 1959, he had perfected Mussolini’s rhetorical gestures, plagiarized some of his phrases, (e.g., “All within the revolution, nothing outside the revolution, nothing against the revolution,” uttered during Castro’s trials to censor Cuban writers, artists, and poets), and his use of grand symbols and theater (e.g., the white doves sitting on his shoulders during a widely photographed 1959 speech). Hitler created a power base out of the alienated German lower classes and Castro played to the farmers and the workers; while imposing social controls, he asked “Elecciones, para qué?” or “Elections, for what?” (Raffy, 2003; Szulc, 1986; Coltman, 2003). After assuming power, his indifference to ordinary rules of adult behavior is seen in the fact that, although he promised to be a good father for his own son Fidelito, he was soon divorced and proceeded to have at least eight other children with several women out of wedlock (Raffy, 2003; Fuentes, 2004).

Education

Castro was educated at Jesuit and La Salle Christian Brothers Schools ) private schools in Santiago de Cuba and the Colegio de Belén in Havana, graduating in 1945. He would later expel the faculty from Cuba, like many other priests and religious figures, and have the schools property nationalized. After high school, Castro enrolled at the University of Havana to study law. Here he joined the Union Insurreccional Revolucionaria (UIR, the Insurrectional Revolutionary Union) an action group led by Emilio Tro ,, , , and became involved in political disputes that were often violent and sometimes murderous.

Early political activity

In 1947 he joined the Partido Ortodoxo (Orthodox Party, also known as the Partido del Pueblo Cubano, Party of the Cuban People) and its campaign to expose government corruption and demand reform. In the summer of 1947, Castro, along with Rolando Masferrer, became part of the Caribbean legion that attempted to travel to the Dominican Republic and overthrow its government . The attempt failed, however, when the Cuban police intervened. Fidel and a few other escaped by rafting and swimming two miles before reaching land. Because of this and his other activities, Castro became known through local radio and the Alerta newspaper.

Bogotazo

In 1948, Castro traveled to Bogotá in Colombia as a delegate of the Federacion Estudiantil Universitaria (FEU, the Cuban University Student Federation) for the ninth Pan-American Union Conference. Some funding for Castro on this trip is understood to have been provided by Juan Peron. During his visit, however, the Colombian Liberal Party leader Jorge Eliecer Gaitán was assassinated. Castro, who according to the Scotland Yard investigation and other sources had set up an appointment with Gaitán at a time immediately before the Colombian leader was killed, and participated in the violence the Bogotazo that followed the assassination (Angel Aparicio Lourencio, 1975). Castro, who was and still is suspected of collaborating with the Colombian Communist Party in this killing, had to flee the country. These claims are controversial, most notably because Fidel was an admirer of Gaitán; however, some maintain that Castro is also known to express admiration of those e.g. Camilo Cienfuegos he is believed to have ordered killed. The plane with which Castro made his escape was provided by the Cuban president, Carlos Prío Socarrás, even though Castro opposed Prío.

Putative early contacts with influential people

During his early days Fidel Castro can be said with some confidence to have been linked to a number of influential and powerful people. These contacts include Fulgencio Batista, who was definitely close to Castro's family.

The mysterious William Wieland (aka (Guillermo) Montenegro, Wilheim Wieland) protégé of Sumner Welles from the time of Fulgencio Batista's first rise to power in 1933. Wieland was present (US consul) during the Bogotazo while it is said by some to be in contact with Castro. Wieland was a highly influential U.S. State Department Official, variously and conflictingly described as a Communist , and as a CIA agent who appears to have aided Castro during the U.S. Arms Embargo Against Batista (1958). Wieland was an active naysayer during the weak planning and execrable execution of the Bay of Pigs Invasion in 1961, and later was subject to various U.S Government investigations (Holland, 2000). While historians have not yet reached consensus; Wieland is commonly considered to have a left of center record in Latin American matters . and quite definitely linked to the influential bisexual underground groups (Bancroft 1983 pp. 132-133) within the US State Department (Paz 2001 pp. 269,270; Welles, 1997). Some sources (citing 245:6572 "State Department Security: The Case of William Wieland", 1962; 245:6573 State Department Security: Testimony of William Wieland", 1962; 245:6574 "State Department Security - 1963-65: The Wieland Case Updated", 1963-1965 ) report that in the 1930s William Wieland, known in Cuba as Arturo Montenegro, was intimate with Sumner Welles and his successor, Jefferson Caffery, thus promoting his successful career .

Prior to his 1956 landing Castro was said to be in contact with KGB agent Nikolai Sergeevich Leonov in Mexico City (see below). Other putative contacts include Rafael Leónidas Trujillo. Castro received money and weapons from Carlos Prío Socarrás whether this included CIA support is not clear.

First Marriage

That same year, 1948, Castro married Mirta Díaz Balart, a philosophy student from another wealthy Cuban family, with whom he later had a son, Fidelito Castro. It is said that Castro fled out of the back door of the church of the Virgin of Charity because some of his enemies were waiting for him . Amongst the wedding presents received was a substantial gift (US$500 others say U.S. $1000) from Batista, who by then was both a retired President and dictator with the rank of former general in the Cuban army.

In 1950 Castro graduated and began practising law in a small partnership, mostly representing the poor. He had by now become known for his nationalist views and his opposition to the United States' influence in Cuba. In 1951, after the Partido Ortodoxo's founder Eduardo Chibás committed suicide, Castro unsuccessfully claimed leadership of the party and prepared to stand for parliament the following year. However, a coup d'état led by Batista on March 10 1952 overthrew Socarrás' government and the elections were canceled. Castro broke away from the Partido Ortodoxo and, in court, charged Batista with violating the Cuban constitution. His petition was refused.

Attack on Moncada Barracks

Castro responded to Batista's coup by organizing an armed attack on the Moncada Barracks, Batista's largest garrison outside Santiago de Cuba, on July 26, 1953. The Céspedes garrison in Bayamo was also attacked under the leadership of Antonio "Ñico" Lopez. These attacks proved unsuccessful and more than sixty of the one-hundred and thirty-five militants involved were killed.

Castro and other surviving members of his group managed to escape to the part of the Sierra Maestra east of Santiago. Castro and his company were captured after a patrol discovered them while they were sleeping. Although the official attitude of the military was to capture Fidel alive, the real orders were that the leader of the rebellion, Fidel Castro, was to be executed once found. However, some say by a strange coincidence, none of the soldiers recognized Fidel, except one person, the lieutenant who led the patrol that captured Fidel. This lieutenant had been at the University of Havana at the same time Fidel was a student there. While he was searching Fidel for weapons, he whispered in Fidel's ear not to reveal his name, or he would be shot. .

However, most credit the good offices of Monseñor Pérez Serantes , as the main reason why the Castro brothers were not executed on capture as was common for their fellow militants . Yet, others suggest that Raul Castro's long relationship with Batista, to the point that Raul is said by some to be Batista's godson , and long established Castro-Batista family influences played a role.

During the subsequent trial in August to October 1953, Castro delivered La historia me absolverá (History Will Absolve Me, complete translation) as his closing speech, in which he defended his actions and declared his political views. He was sentenced to fifteen years in prison.

While he was in prison, Mirta Díaz-Balart divorced Castro and his enemies are said to have tried to poison him (BBC claims over 600 often baroque and always failed attempts on his life). Having served less than two years, however, he was released in May 1955 thanks to a general amnesty from a confident Batista. He went into exile in Mexico on July 7.

Some historians claim that although Castro's group took part in the Moncada Barracks attack, Castro himself was not involved in the fighting. They claim that Castro and his inner circle hid at a nearby location, away from the bloodshed. These claims, however, are highly disputed. It has also been claimed that Castro's unit targeted soldiers who were sleeping or incapacitated in the barracks' infirmary. This claim has been countered as an attempt by Castro's enemies to discredit him. In La historia me absolverá, Castro said:

Everyone had instructions, first of all, to be humane in the struggle... From the beginning we took numerous prisoners - nearly twenty... Those soldiers testified before the court and without exception they all acknowledged that we treated them with absolute respect.... In line with this, I want to give my heartfelt thanks to the prosecutor for one thing in the trial of my comrades: when he made his report he was fair enough to acknowledge as an incontestable fact that we maintained a high spirit of chivalry throughout the struggle.

Life as a guerrilla

Once in Mexico, Castro reunited with other exiles and founded the 26th of July Movement. They went to the United States, where they gathered funds from Cubans living in that country and the United States especially from Carlos Prío Socarrás the elected Cuban president who was deposed by Fulgencio Batista in 1952. Regular and cordial contacts with the KGB agent Nikolai Sergeevich Leonov in Mexico City did not result in weapon supply (Andrew and Gordievsky, 1990). Medical doctor Ernesto "Che" Guevara joined the group in Mexico. In Mexico the group trained under Spanish Civil War Veteran, Cuban born , Alberto Bayo Giraud, , who had fled Francisco Franco's victory to Mexico. On November 26 1956 they returned to Cuba, sailing from Tuxpan to Cuba on the 60-ft pleasure yacht Granma. Two "traitors" are mentioned before the yacht sailed Evaristo Venereo and Rafael del Pino (the del Pino who had been with Castro in the Bogotazo, )

The expeditionaries landed in Los Cayuelos near the eastern city of Manzanillo on December 2, 1956. They missed their scheduled arrival by two days. On November 30th, another group of Castro's supporters, wearing olive green uniforms and the 26th of July Movement's red & black insignias, staged a street revolt in Santiago, organized by Frank Pais. While some state that only between twelve and sixteen of the original eighty-three men of the Granma group survived encounters with the Cuban army, and fled to the Sierra Maestra mountains, a careful breakdown of the events, indicate three were killed at Alegría de Pío (Israel Cabrera, Humberto Lamotte and Oscar Rodríguez; José Ponce Díaz was severely wounded ), The rest dispersed. Of the 80 remaining 21 were captured and executed, 22 were held prisoner; of the remaining 37 about 20 escaped (7 rejoined the rebels) and some 17-20 reached the high mountains (Cuban web sources e.g and Thomas, 898-900). These survivors were aided by a group that included Celia Sanchez Manduley, Huber Matos and bandit Cresencio Perez's relatives. Some are now said to have been members of covert branch of the communist party or "agrarian reformers" . The survivors, who included Che Guevara, Raúl Castro, and Camilo Cienfuegos, reformed into the José Martí column under Castro's command. There were a number of purges usually carried out by Che Guevara, even one expeditionary, “Gallego” Morán, was declared a traitor and executed in Guantánamo Castro's movement gained popular support and grew to over eight hundred men. In mid-1957 Castro gave Che Guevara command of a second column. A journalist, Herbert Matthews from the New York Times, came to interview him in the Sierra Maestra, attracting interest to his cause in the United States. This was followed up by the TV television crew of Andrew Saint George said to be a CIA contact person. Castro's colorful command of the English enabled him to appeal directly to a US audience. He then became viewed as a revolutionary leader in the United States.

On May 24, 1958, Batista launched seventeen battalions (about 10,000 soldiers) against Castro and other anti-government groups in Operación Verano called "la Ofensiva" by the rebels (Alarcón Ramírez,1997). Despite being heavily outnumbered, Castro's forces scored a series of victories, in part aided by desertion from Batista's army. Whilst subsequent pro-Castro Cuban sources emphasize Castro and his group's role in these battles, other groups and leaders were involved, such as escopeteros (poorly-armed irregulars). It is also claimed that Guevara received excessive credit, when in one instance it is alleged he abandoned another anti-Batista leader René Ramas Latour to fight to his death.

As Operación Verano faltered, Castro ordered three columns under Guevara, Jaime Vega and Camilo Cienfuegos to invade central Cuba where they were strongly supported by elements of Column One, nominally directed by Universo Sánchez and by veteran plains Escopeteros such as the "Muchachos de Lara" who had long been operating in the area. Castro's own column (Columna Uno) pushed past Bueycito out onto the Cauto Plains. Here they were now supported by Huber Matos, Raul Castro and others to the eastern most part of the province. On the plains Castro's forces first surrounded Guisa and drove out their enemies, and proceeded to take most of the towns that were taken by Calixto Garcia in the 1895-1898 Cuban War of Independence. In December 1958, Guevara and Cienfuegos' columns joined with other anti-Batista forces already in the central mountains, occupied several towns and then attacked Santa Clara, the capital of the Las Villas province. Guevara derailed an armored train which Batista had sent to aid his troops trapped inside the city and Batista's forces then crumbled. On December 28, 1958 Castro met semi-secretly with Batista General Eulogio Cantillo who arrived at Castro's headquarters in a helicopter. Fearing the worst and expecting betrayal of his own army, Batista and president-elect Andrés Rivero Agüero(see Carlos Rivero Agüero) fled Cuba on the night of December 31, 1958, initially to the Dominican Republic and then to Francisco Franco's Spain.

Early years in power

On January 1, 1959, Castro's forces entered Havana and on January 5 the liberal law professor José Miró Cardona created a new government with himself as prime minister and Manuel Urrutia Lleó as president. On January 8 Castro himself arrived in Havana and assumed the post of Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces. In February, however, Miró resigned and Castro assumed the role nearly a month later after initially rejecting the offer; and in July, Urrutia resigned and was replaced by Osvaldo Dorticós Torrado, a lawyer more sympathetic to Castro's ideology.

Initially the United States was quick to recognize the new government. On April 15 Castro went on a famous twelve day unofficial tour of the US, where he met Malcolm X, Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser and Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru while staying in a cheap hotel in Harlem - an example of his tendency to 'mix with the people', as he later also did in Panamá, where he used the service entrance of the hotel more than the front door. He subsequently visited the White House and met with Vice President Richard Nixon. Sometime during this period Castro spoke for his first time to members of the Council of Foreign Relations.

Castro's economic policies had caused some concerns in Washington that Castro was a Communist with an allegiance to the Soviet Union. Supposedly, President Dwight D. Eisenhower snubbed Castro, giving the excuse that he was playing golf, and left Nixon to speak to him. Following the meeting, Nixon remarked that Castro was "either incredibly naïve about Communism or under Communist discipline — my guess is the former. " Castro spent two days in Canada, initiating a friendship with future Canadian Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau.

Friction with the US soon developed when, in May 1959, the new government began expropriating US-owned property (much owned by US-owned corporations, such as the United Fruit Company) in accordance with the First Agrarian Reform Law. Compensation for the expropriated properties was based on their declared property tax value, which, for many years, the same companies had managed to keep artificially low. In June 1960, Eisenhower reduced Cuba's sugar import quota by 700,000 tons, and in response, Cuba nationalized some $850 million worth of US property and businesses. The revolutionary government consolidated control of the nation by nationalizing industry, expropriating property owned by Cubans and non-Cubans alike, collectivizing agriculture, and enacting policies which it claimed would benefit the population. These policies alienated many former supporters of the revolution among the Cuban middle and upper-classes, who made up roughly half of the Cuban population. Over one million Cubans later migrated to the US, forming a vocal anti-Castro community in Miami, Florida Cuban-American lobby.

According to Andrew and Gordievsky (1990) as early as July 1959 Castro's intelligence chief Ramiro Valdés contacted the KGB in Mexico City, the USSR sent over one hundred mostly Spanish speaking advisors; including Enrique Lister Farjan to organize the Committees for the Defense of the Revolution. In February 1960 Cuba signed an agreement to buy oil from the USSR. When the US-owned refineries in Cuba refused to process the oil, they were expropriated, and the United States broke off diplomatic relations with the Castro government soon afterward. To the concern of the Eisenhower administration, Cuba began to establish closer ties with the Soviet Union. A variety of pacts were signed between Castro and Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev, allowing Cuba to receive large amounts of economic and military aid from them.

Bay of Pigs

Main article: Bay of Pigs InvasionOn April 15, 1961, the day after Castro described his revolution as socialist, four Cuban airfields were bombed by A-26s bearing false Cuban markings. These bombing runs were the beginning stages of the Bay of Pigs invasion. The United States staged an unsuccessful attack on Cuba on 17 April, 1961. Assault Brigade 2506, a force of about 1,400 Cuban exiles, financed and trained by the Central Intelligence Agency, and commanded by Cuban Manuel Artime and CIA operatives Grayston Lynch and William Robertson, landed perhaps a hundred miles south-east of Havana, at Playa Girón on the Bay of Pigs. Under the leadership of Stephen Penney, the CIA assumed that the invasion would spark a popular uprising against Castro; the operation itself was expected by Castro, however, and in anticipation the government rounded up perhaps 100,000 (Lynch reports 250,000) anti-Castro Cubans -at least 20,000 in Havana alone (Priestland, 2003), executed some and imprisoned the others under threat of death should the invasion succeed. Led by Erneido Oliva, most of the 1,200 men invasion force made it ashore; however, reserve ammunition in two US supplied support ships, the Houston and the Río Escondido, sunk by Cuban Air Force Sea Fury propeller-driven aircraft and T-33 Jets, was lost. President Kennedy was influenced by some State Department officials including Roy Rubottom and especially his assistant William Weiland who had been involved in Castro related matters since the Bogotazo and in Cuban matters 1933 as assistant to Sumner Welles. Kennedy withdrew support for the invasion at the last minute, by canceling several bombing sorties that could have crippled the entire Cuban Air Force. The cancellation also prevented US Marines waiting off the coast from landing in support of the Cuban exiles. After three days of ferocious fighting in which about 100 invaders and perhaps 2,000 militia, perhaps 5000 according to Lynch, more died (most trapped in buses on the causeways), the rest of the invaders were captured . At least nine invaders were formally executed in connection with this action, however, a number died of suffocation in an unventilated truck trailer, while Castro attributed the defeat of the invasion to his leadership.

In a nationally broadcast speech on 1961-12-02, Castro declared that he was a Marxist-Leninist and that Cuba was going to adopt Communism. On February 7, 1962, the US imposed an embargo against Cuba, which included a general travel ban for American tourists.

October Crisis

Main article: Cuban Missile CrisisTensions between Castro and US heightened during the 1962 Cuban missile crisis, which nearly brought the USSR and the US to direct confrontation. Khrushchev conceived the idea of placing missiles in Cuba as a deterrent to a US invasion. After consultations with his military advisors, he met with a Cuban delegation led by Raúl Castro in July in order to work out the specifics. It was agreed to deploy Soviet R-12 MRBMs on Cuban soil; however, American Lockheed U-2 reconnaissance discovered the construction of the missile installations on 15 October, 1962 before the weapons had actually been deployed. The US government viewed the installation of Soviet nuclear weapons 90 miles south of Key West as an aggressive act and a threat to US security. As a result, the US publicly announced its discovery on 22 October, 1962, and implemented a quarantine around Cuba that would actively intercept and search any vessels heading for the island. Nikolai Sergeevich Leonov, who would become General in KGB Intelligence Directorate , and Soviet KGB deputy station chief in Warsaw , was the translator Castro used for contact with the Russians.

In a personal letter to Khrushchev dated 27 October, 1962, Castro urged Khrushchev to launch a nuclear first strike against the United States if Cuba were invaded, but Khrushchev rejected any first strike response (pdf). Soviet field commanders in Cuba were, however, authorized to use tactical nuclear weapons if attacked by the United States. Khrushchev agreed to remove the missiles in exchange for a US commitment not to invade Cuba and an understanding that the US would remove American MRBMs targeting the Soviet Union from Turkey and Italy, a measure that the US never implemented.

Cuban Missile Crisis

Further information: nuclear weaponsIn a televised speech on October 22, 1962, American President John F. Kennedy publicly announced that the USSR had begun to deploy medium and intermediate-range nuclear missiles in Cuba, approximately 145 km (90 mi) from Florida. Moreover, the president said, by their doing so the Soviets had demonstrated that they had for many months been lying about their intentions in that island nation. Kennedy then stated that the United States was prepared to not only blockade Cuba but to ultimately do whatever might be necessary to remove the missiles. Finally, he warned, a Soviet attack on any target in the United States or Latin America would result in what he called "a full retaliatory response on the Soviet Union." In the days that followed Kennedy's address, Soviet ships moved toward a line of U.S. naval vessels that had been set up as a blockade to "quarantine" Cuba. The U.S. government's intention was to force the Soviets to ship their missiles back to the Soviet Union. By October 27, the superpowers seemed near to war. As the Soviet missile sites reached completion, the American pilot of a U-2 spy plane was shot down over Cuba and the pilot killed. Also during that time, President Kennedy ordered 180,000 combat-ready troops deployed to the southeastern United States to prepare to attack Cuba. On October 28, however, just before 9:00 EST, Soviet chairman Nikita Khrushchev announced in a broadcast over Radio Moscow that he would accept Kennedy's pledge not to invade Cuba in return for a Soviet pledge to remove the missiles from the island. Cuban leader Fidel Castro was outraged at what he felt was a Soviet betrayal, but he reluctantly allowed the missiles to be withdrawn. The stark reality of the Cuban Missile Crisis only became clear decades later, the result of a joint U.S.-Russian-Cuban research project (the Cuban Missile Crisis Project), which sponsored six international conferences between 1987 and 2002 that included some of the major players from both sides who had taken part in the confrontation.

As a result of these conferences and continuing research, it is now clear that the key sources of the crisis were the enormous, mutual misperceptions and misunderstandings between Washington and Moscow and Havana. The Soviets, for example, felt that they had to deploy the missiles to Cuba because they believed (incorrectly, but understandably, following the abortive Bay of Pigs invasion of April 1961) that a massive U.S. assault on Cuba was imminent. On the other hand, the United States dismissed growing signs of the possibility of a Soviet deployment of nuclear missiles to Cuba because the Soviets had never before positioned such weapons outside the Soviet Union, and because it was so obvious (to the United States, though not to the Soviets) that such a move would be totally unacceptable in Washington. In addition, the Soviets felt sure (though the Cubans tried several times to persuade them that they were wrong) that the missiles could be introduced into Cuba secretly, via a clandestine operation supplemented by a systematic attempt to deceive the United States.

Thus the danger of the confrontation in 1962 was more severe than U.S. leaders, from Kennedy on down, believed at the time. Recent revelations from the Cuban Missile Crisis Project have shown that any U.S. attack on Cuba would have also been an attack on more than 40,000 Soviet citizens who were deployed chiefly around the missile sites, which would have been the primary targets. At the time, the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) estimated that fewer than 10,000 Soviets had arrived on the island.

Furthermore, by the last weekend of October 1962, Castro had concluded that a U.S. air strike and invasion of Cuba was all but inevitable. This led him to request of Khrushchev, in a cable sent on October 27, that in the event of an invasion, the Soviet leader launch an all-out nuclear strike against the United States. If Cuba was to be destroyed, Castro urged the Soviets to take the United States down with it. Cuba would thus be a martyr for the socialist cause. Also by October 27, when the majority of President Kennedy's military and civilian advisors were advocating an attack on Cuba, the Soviets had already delivered 162 nuclear warheads to that country. The CIA believed at the time that there were no warheads on the island. During the last few days of the crisis, the Soviet field commander ordered the warheads for the short-range, tactical weapons moved out of storage and closer to their launchers. He did so without prior approval from Moscow, and he likely would have ordered their use in the event of a U.S. invasion. A further fact uncovered is that each Soviet submarine escorting ships bound for Cuba carried one nuclear-tipped torpedo, which could be used without consultation with Moscow. One such submarine, certain that it was under attack from U.S. vessels and that war may have already begun, came very close to launching its nuclear weapon against the U.S. fleet blockading Cuba, an action that might well have led to a U.S. nuclear response.

Thus the Cuban Missile Crisis Project came to the conclusion that by the last weekend of October 1962, all the pieces were in place for Armageddon to occur. Some 250,000 Cuban troops and more than 40,000 Soviet troops armed with dozens of tactical nuclear weapons would have met a U.S. invasion force (which would not have been equipped with nuclear weapons), initiating nuclear war in the (mistaken) assumption that the United States would have attacked with nuclear weapons. Historians speculate that such an action would very likely have ended in nuclear catastrophe. In the end, President Kennedy rejected military advice for a full-scale surprise attack on Cuba and instead delivered the public ultimatum to the USSR on October 22, declaring the quarantine and demanding the withdrawal of all offensive missiles. After nearly a week of unprecedented tension, the Khrushchev government yielded. Kennedy, in return, agreed to refrain from attempting an overthrow of Castro's government. Despite this concession, all sides regarded the outcome as a substantial victory for the United States, and Kennedy won a reputation as a formidable international statesman. The USSR, for its part, began a long-term effort to strengthen its military capability, but in the immediate future both nations sought to relax hostilities.

Relations with the outside world

Following the establishment of diplomatic ties to the Soviet Union, and the Cuban Missile Crisis, Cuba became increasingly dependent on Soviet markets and military and economic aid. Castro was able to build a formidable military force with the help of Soviet equipment and military advisors. The KGB kept in close touch with Havana, and Castro tightened Communist Party control over all levels of government, the media, and the educational system, while developing a Soviet-style internal police force.

Castro's alliance with the Soviet Union caused something of a split between him and Guevara, who took a more pro-Chinese view following ideological conflict between the CPSU and the Maoist CPC. In 1966, Guevara left for Bolivia in an ill-fated attempt to stir up revolution against the country's government.

On 23 August, 1968 Castro made a public gesture to the Soviet Union that reaffirmed their support in him. Two days after the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia to repress the Prague Spring, Castro took to the airwaves and publicly denounced the Czech rebellion. Castro warned the Cuban people about the Czechoslovakian 'counter-revolutionaries', who "were moving Czechoslovakia towards capitalism and into the arms of imperialists". He called the leaders of the rebellion "the agents of West Germany and fascist reactionary rabble." In return for his public backing of the invasion, at a time when many Soviet allies were deeming the invasion an infringement of Czechoslovakia's sovereignty, the Soviets bailed out the Cuban economy with extra loans and an immediate increase in oil exports.

In 1971, following the re-establishment of diplomatic relations with Cuba, despite a previously established Organization of American States convention that no nation in the Western Hemisphere would do so (the only exception being Mexico, which had refused to adopt that convention), Cuban president Fidel Castro took a month-long visit to Chile. The visit, in which Castro participated actively in the internal politics of the country, holding massive rallies and giving public advice to Allende, was seen by those on the political right as proof to support their view that "The Chilean Way to Socialism" was an effort to put Chile on the same path as Cuba.

On November 4, 1975, Castro ordered the deployment of Cuban troops to Angola in order to aid the Marxist MPLA-ruled government against the UNITA opposition forces, which gained the support of the government of South Africa. A reluctant Moscow aided the Cuban initiative with the USSR engaging in ten airlifts of Cuban forces into Angola. On this, Nelson Mandela has remarked "Cuban internationalists have done so much for African independence, freedom, and justice." Cuban troops were also sent to Marxist Ethiopia to assist Ethiopian forces in the Ogaden War with Somalia in 1977. In addition, Castro extended support to Marxist Revolutionary movements throughout Latin America, such as aiding the Sandinistas in overthrowing the Somoza dictatorship in Nicaragua in 1979.

When Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev visited Cuba in 1989, the close relationship between Moscow and Havana was strained by Gorbachev's implementation of economic reforms. "We are witnessing sad things in other socialist countries, very sad things," stated Castro in November 1989, in reference to the reforms that were sweeping such communist allies as the Soviet Union, East Germany, Hungary, and Poland. The Soviet Union had subsidized the Cuban economy for decades, paying $1.23 per pound for sugar while the world market price of which had been steady between 17 and 22 cents per pound. According to Castro, "the sun vanished from the horizon when the Soviet Union collapsed." Cuba entered what it called the "Special Period". . The effects were immediate and devastating.

Remaining as president

In 2005, American business and financial magazine Forbes listed Castro among the world's richest people, with an estimated net worth of $550 million.. As a result of Forbes' comments, Castro is considering filing a lawsuit against the magazine, claiming the accusations are false and the article was meant to defame him.

Religion

Castro is an atheist and has not been a practicing Roman Catholic since his childhood. Pope John XXIII excommunicated Castro on January 3, 1962 on the basis of a 1949 decree by Pope Pius XII forbidding Catholics from supporting communist governments. For Castro, who had previously renounced his Catholic faith, this was an event of very little consequence, nor was it expected to be otherwise. It was primarily aimed at undermining support for Castro among Catholics.

In 1992, Castro agreed to loosen restrictions on religion and even permitted church-going Catholics to join the Cuban Communist Party. After Pope John Paul II denounced the US embargo on Cuba as "unjust and ethically unacceptable", the relationship between the Vatican and Castro improved. John Paul II visited Cuba in 1998, the first visit by a ruling pontiff to the island. Castro and the Pope appeared side by side in public on several occasions during the visit; the Pope generally stayed away from overt political themes, instead emphasizing that his trip was designed to strengthen the Catholic Church in Cuba. However, he criticized widespread abortion in Cuban hospitals as well as urged Castro to end the government's monopoly on education, in order to allow the return of Catholic schools. Following the visit, Cubans were again allowed to mark Christmas as a holiday and to openly hold religious processions.

After the Pope's death in April 2005, Castro attended a mass in his honor in Havana's cathedral. He had last visited the cathedral in 1959, 46 years earlier, for the wedding of one of his sisters. Cardinal Jaime Ortega, who led the mass, welcomed Castro, who was dressed in a dark suit, and expressed his gratitude for the "heartfelt way the death of our Holy Father John Paul II was received (in Cuba)."

Human rights in Cuba

Main article: Human rights in CubaSome studies report that thousands of political opponents have been killed during Castro's decades-long leadership. ; however, given the nature of the sources of this information and how it is tabulated, including or not including those dead in Cuban external and internal wars, exact numbers are not known. Some Cubans who have been labeled "counterrevolutionaries", "fascists", or "CIA operatives" have been imprisoned in extremely poor conditions without trial; at least some have been summarily executed. Military Units to Aid Production, or UMAP's were labor camps established in 1965, according to Castro, for "people who have committed crimes against revolutionary morals" in order to work counter-revolutionary influences out of certain segments of the population.

Citing previous US hostility, supporters of Castro thus portray active opposition to the Cuban government as illegitimate, and the result of an ongoing conspiracy fostered by Cuban exiles with ties to the United States or the CIA. Many Castro supporters say that Castro's measures are justified to prevent the United States from installing a puppet leader in Cuba. Castro's opposition say he uses the United States as an excuse to justify his continuing political control.

Popular image

Since Fidel Castro came to power, he and his government have exhibited many traits of personalist rule commonly attributed to a cult of personality, despite attempts to discourage it. In contrast to many of the world's modern strongmen, Castro has only twice been personally featured on a Cuban stamp. In 1974 he appeared on a stamp to commemorate the visit of Leonid Brezhnev, and in 1999 he appeared on a stamp commemorating the 40th anniversary of the Revolution. There has been a strong tendency to encourage reverence for other Cuban figures such as José Martí, Che Guevara, and the "martyrs" of the Cuban revolution such as Camilo Cienfuegos.

The Cuban government, specifically the CDR, frequently puts up billboards and posters with propaganda slogans. Castro features prominently in much of this, his own persona being intertwined with the Cuban flag and identity, and the revolution itself. Fidel rarely appears in public without his military fatigues, and is famous for giving speeches which often last several hours. Large crowds of people gather to cheer at these fiery speeches. This style of leadership has led to a common characterization of Castro as being a subject of a personality cult, especially by critics.

However, in contrast to most personality cults, the details of Castro's private life, particularly those concerning his family members, are scarce. However, the spread of satellite technology seems to be eroding this . He is also not the only individual that figures prominently in official propaganda, as fellow Cuban revolutionary Che Guevara appears not only on billboards and posters, but on the sides of buildings and especially on various trinkets sold to tourists. It was said that this sort of posthumous imposition of a personality cult is similar to the usage of Vladimir Lenin's persona during the era of Joseph Stalin in the Soviet Union, in that a deceased leader is invoked in support of government policies and the state itself. Castro, however, has always maintained that there exists no such thing:

We have never preached cult of personality. You will not see a statue of me anywhere, nor a school with my name, nor a street, nor a little town, nor any type of personality cult because we have not taught our people to believe, but to think, to reason out.

Family and health

Fidel Castro's parents were Lina Ruz González and Ángel Castro y Argiz. He has two brothers: Ramón (born in 1924), Raúl (born in 1931) and at least two sisters Juanita Castro Ruz who lives in Miami, Florida and Agustina Castro Ruz who lives in Havana. By his first wife Mirta Díaz-Balart, he has a son named Fidel "Fidelito" Castro Díaz-Balart. Mirta left Cuba in 1954 taking Fidelito with her, and she divorced Castro later the same year. Fidelito was later returned to Cuba. Mirta now lives in Spain. Fidel has four sons named Alex, Alexis, Antonio, and Alejandro with his second wife Dalia Soto del Valle. Mrs Soto del Valle is a mysterious figure believed to an excellent administrator and to have a residence in France as well as in Cuba ]. As becoming for leader of such overwhelming power Castro's private life is most satisfactory and comfortable .

During his days in the Sierra, Castro was linked romantically with much beloved fellow rebel Celia Sánchez. While Fidel was still married to Mirta, he had an affair with Naty Revuelta which resulted in a daughter named Alina Fernandez-Revuelta. Alina left Cuba in 1993, disguised as a Spanish tourist to avoid emigration restrictions. She now lives in the United States.

There has been speculation about Castro's health since he apparently fainted during a seven-hour speech under the Caribbean sun in June 2001. His doctors say his health is improving.

During 2004, there was further speculation about the state of Castro's health. In January 2004, Luis Eduardo Garzón, the mayor of Bogotá, said that Castro "seemed very sick to me" following a meeting with him during a vacation in Cuba. (url) In May 2004, Castro's physician denied that his health was failing, and speculated that he would live to be 140 years old, a somewhat typical Cuban overexaggeration for effect. Dr. Eugenio Selman Housein said that the "press is always speculating about something, that he had a heart attack once, that he had cancer, some neurological problem", but maintained that Castro was in good health. (url)

On 20 October 2004, Castro fell off a stage following a speech he gave at a rally in Santa Clara. The fall fractured his knee and arm. He underwent three hours and 15 minutes of surgery to repair his left kneecap, which was fractured into eight pieces.

Following his fall, Castro wrote a letter that was read on Cuban television and published in newspapers. In it, he assured the public that he was fine and would "not lose contact with you." (url) A government statement added: "His general health is good, and spirits are excellent."

By November, Castro surprised many when he suddenly stood up from his wheelchair during a state visit by Chinese President Hu Jintao, leaning on a metal cane with an arm support. The following month, he stood unassisted for several minutes during a visit by Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez.

Finally, cheered by hundreds of lawmakers, a smiling Castro walked in public for the first time since shattering his kneecap in the fall after only two months. Legislators looked stunned, then smiled and applauded, when Cuba's then 78-year-old president entered the main auditorium of the Convention Palace on the arm of a uniformed schoolgirl to attend a year-end National Assembly meeting.

Because of his large role in Cuba, his well-being has become a continual source of speculation, both on and off the island, as he has grown older. Castro's quick recovery from breaking his left kneecap into eight pieces was likely to dampen the latest round of rumors questioning his health.

An AP report alleges that Castro has Parkinson's disease after rumors have been going around for years. Castro denies such allegations, as reported by Reuters news service.

References

- Cuba: Anatomy of a Revolution

- "Castro: The great survivor" BBC story.

- Online Newshour: Fidel Castro -- February 12, 1985 Interview with Fidel Castro

Further reading

- Alarcón Ramírez, Dariel ("Benigno")1997 Memorias de un Soldado Cubano: Vida y Muerte de la Revolución. Tusquets Editores S.A. Barcelona, ISBN 848319942

- Alexe, Vladimir 2003 (accessed 20/01/2006) Fidel Castro: biografia secreta Bucuresti. Ziua Sambata, 20 septembrie 2003 http://www.ziua.ro/archive/2003/09/25/docs/26853.html

- Ameringer, Charles D 1995 The Caribbean Legion Patriots, Politicians, Soldiers of Fortune, 1946-1950 Pennsylvania State University Press (December, 1995) (Paperback) ISBN 0271014520

- Álvarez Batista, Gerónimo 1983. III Frente a las puertas de Santiago. Editorial Letras Cubanas, Havana.

- Ames, Michaela Lajda; Mendoza, Plinio Apuleyo; Montaner, Carlos Alberto; Llosa, Mario Vargas; Montaner, Carlos Alberto. Guide to the Perfect Latin American Idiot.

- Anderson, Jon Lee 1997. Che Guevara: A Revolutionary Life, Bantam Press, ISBN 0553406647 or Grove Press, ISBN 0-8021-1600-0

- Aparicio Laurencio, Angel 1975 "Antecedentes desconocidos del nueve de abril" Ediciones Universal, Madrid. ISBN 8439913362

- Batista, Fulgencio 1960 Repuesta. Manuel León Sánchez S.C.L., Mexico D.F

- Bancroft, Mary 1983. Autobiography of a spy. William Morrow and Company. Inc. New York. ISBN 0688020194

- Bonachea, Ramon L and Marta San Martin 1974. The Cuban insurrection 1952-1959. Transaction Publishers, New Brunswik, New Jersey ISBN 0878555765

- Castro, Fidel, History Will Absolve Me, Editorial de Ciencias Sociales, La Habana, 1975

- de la Cova, Antonio Rafael (In Press) The Moncada Attack: Birth of the Cuba Revolution University of South Carolina Press

- Fontanova, Humberto 2005 Fidel: Hollywood's Favorite Tyrant. Regnery Publishing Company, Washington DC. ISBN 0895260433

- Franqui, Carlos (Translator Albert B. Teichner) 1968 The Twelve. Lyle Stuart New York ISBN 0818400897 Carlos Franqui

- Fuentes, Norberto 2005 La Autobiografia de Fidel Castro. Destino Ediciones. ISBN: 9707490012

- Geyer, Georgie Anne 2002 Guerrilla Prince. Andrews McMeel Publishing Kansas City ISBN 0740720643

- Gonzalez, Servando 2002 The Secret Fidel Castro: Deconstructing the Symbol. Spooks Books, U.S. ISBN 0971139105 ISBN 0971139113

- Gott, Richard (2004). Cuba: A New History. Yale University Press. ISBN 0300104111

- Guevara, Ernesto “Che” (and Waters, Mary Alice editor) 1996 Episodes of the Cuban Revolutionary War 1956-1958. Pathfinder New York. ISBN 0873488245

- Holland, Max 1999 A Luce Connection: Senator Keating, William Pawley, and the Cuban Missile Crisis. Journal of Cold War Studies 1.3, 139-167.

- Johnson, Haynes 1964 The Bay of Pigs: The Leaders' Story of Brigade 2506. W. W. Norton & Co Inc. New York. 1974 edition ISBN 0393042634

- Lagas, Jacques 1964 Memorias de un capitán rebelde. Editorial del Pácifico. Santiago, Chile.

- Lazo, Mario 1968 Dagger in the heart: American policy failures in Cuba. Twin Circle. NewYork

- Martin, Lionel 1978 The Early Fidel: Roots of Castro's Communism Lyle Stuart, Secaucus New Jersey; 1st ed edition ISBN 0818402547 p. 25.

- Matos, Huber, 2002. Como llego la Noche. Tusquet Editores, SA, Barcelona. ISBN 848310944

- Morán Arce, Lucas 1980 La revolución cubana, 1953-1959: Una versión rebelde Imprenta Universitaria, Universidad Católica; ISBN B0000EDAW9

- de Paz-Sánchez, Manuel 1997. Zona Rebelde. La diplomacia Española ante la revolución cubana. Litografía Romero. S.A. Santa Cruz de Tenerife, Canary Islands, Spain ISBN 847926263X

- de Paz-Sánchez, Manuel 2001. Zona de Guerra. España ante la Revolución Cubana. Litografía Romero. S.A. Santa Cruz de Tenerife, Canary Islands, Spain ISBN 8479263644

- Priestland, Jane (editor) 2003 British Archives on Cuba: Cuba under Castro 1959-1962. Archival Publications International Limited, 2003, London ISBN 1903008204

- Rojo del Río, Manuel. 1981 La Historia Cambio En La Sierra. Editorial Texto, San José, Costa Rica 2a Ed. Aumentada

- Ros, Enrique 2003 Fidel Castro y El Gatillo Alegre: Sus A~nos Universitarios (Coleccion Cuba y Sus Jueces) Ediciones Universal Miami ISBN 1593880065

- Thomas, Hugh. 1998 Cuba or The Pursuit of Freedom. Da Capo Press, New York Updated Ed. ISBN 0-306-80827-7

- U.S. State Department 1950-1954. Confidential Central files Cuba 1950-1954 Internal Affairs Decimal Numbers 737, 837 and 937, Foreign Affairs decimal numbers 637 611.37 Microfilm Project University of Publications of America, Inc. http://www.latinamericanstudies.org/us-cuba/Confidential_Files-Nov-1952-July-1953.pdf http://www.latinamericanstudies.org/us-cuba/Confidential_Files-Aug-1953-Oct-1954.pdf

See also

- Politics of Cuba

- List of dictators

- List of national leaders

- List of Presidents of Cuba

- Opposition to Fidel Castro

- Operation Northwoods

- Comandante - a 2003 documentary film by Oliver Stone

- Fidel (film) - a 2002 movie by David Attwood

External links

By Fidel Castro

- Archive of Fidel Castro's speeches in 6 languages

- Fidel Castro History Archive at Marxists Internet Archive.

- Collection of Castro's speeches

About Fidel Castro

- Fidel Castro biography with pictures and sound clips

- Official Site for Fidel: The Untold Story (2001)

- "A Visit With Castro" Arthur Miller tells about his encounter with Castro (December 24, 2003) in The Nation.

- Cuban exile Humberto Fontova about Castro and Cuba

- Cuba: Socialism and Democracy by Peter Taaffe

- CIA Inspector General's Report on Plots to Assassinate Castro

- Cidob biography in Spanish

- PBS American Experience Interactive site on Fidel Castro with a teacher's guide

- Prominent People - Fidel Castro

About Cuba

- Zenith and Eclipse: A Comparative Look at Socio-Economic Conditions in Pre-Castro and Present Day Cuba, Bureau of Inter-American Affairs, 9 February 1998

- Human Rights Watch - Publication by Human Rights Watch comments about Cuba.

- Political and other freedoms in Cuba - a report by FreedomHouse.

Continuous Coverage on Cuba - by NewsMax.com.

Prohibited Books in Cuba - by Center for a Free Cuba.

State Department on Repression in Cuba - Released by the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor and the Bureau of Public Affairs

Castro in arts

- Fidel Castro at IMDb

| Preceded byJosé Miró Cardona | Prime Minister of Cuba 1959–1976 |

Succeeded by(position abolished 1976) |

| Preceded byOsvaldo Dorticós Torrado | President of Cuba 1976–present |

Succeeded byIncumbent(indefinite) Raúl Castro (designated) |