This is an old revision of this page, as edited by WLU (talk | contribs) at 13:15, 21 January 2012 (Undid revision 472386181 by Tylas (talk) per WP:IRELEV; we don't have an image of Janet). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 13:15, 21 January 2012 by WLU (talk | contribs) (Undid revision 472386181 by Tylas (talk) per WP:IRELEV; we don't have an image of Janet)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) Not to be confused with Dissocial personality disorder. "Split personality" redirects here. For other uses, see Split personality (disambiguation). Medical condition| Dissociative identity disorder | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Psychiatry, psychology |

| Frequency | 1.5% (United States) |

Dissociative identity disorder (DID) is a psychiatric diagnosis and describes a condition in which a person displays multiple distinct identities (known as alters or parts), each with its own pattern of perceiving and interacting with the environment.

In the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems the name for this diagnosis is multiple personality disorder. In both systems of terminology, the diagnosis requires that at least two personalities (one may be the host) routinely take control of the individual's behavior with an associated memory loss that goes beyond normal forgetfulness; in addition, symptoms cannot be the temporary effects of drug use or a general medical condition. DID is less common than other dissociative disorders, occurring in approximately 1% of dissociative cases, and is often comorbid with other disorders.

There is a great deal of controversy surrounding the topic of DID. The validity of DID as a medical diagnosis has been questioned, and some researchers have suggested that DID may exist primarily as an iatrogenic adverse effect of therapy. DID is diagnosed significantly more frequently in North America than in the rest of the world.

Signs and symptoms

Individuals diagnosed with DID demonstrate a variety of symptoms with wide fluctuations across time; functioning can vary from severe impairment in daily functioning to normal or high abilities. Symptoms can include:

- Disruption of identity characterized by two or more distinct personality states

- Multiple mannerisms, attitudes and beliefs

- Pseudoseizures or other conversion symptoms

- Somatic symptoms that vary across identities

- Distortion or loss of subjective time (a long time)

- Current memory loss of everyday events

- Depersonalization

- Derealization

- Depression

- Flashbacks of abuse/trauma

- Sudden anger without a justified cause

- Frequent panic/anxiety attacks

- Unexplainable phobias

Patients may experience a broad array of other symptoms that may appear to resemble epilepsy, schizophrenia, anxiety disorders, mood disorders, post traumatic stress disorder, personality disorders, and eating disorders.

Physiological findings

Reviews of the literature have discussed the findings of various psychophysiologic investigations of DID. Many of the investigations include testing and observation in a single person with different alters. Different alter states have shown distinct physiological markers and some EEG studies have shown distinct differences between alters in some subjects, while other subjects' patterns were consistent across alters.

Neuroimaging studies of individuals with dissociative disorders have found higher than normal levels of memory encoding and a smaller than normal parietal lobe.

Another study concluded that the differences involved intensity of concentration, mood changes, degree of muscle tension, and duration of recording, rather than some inherent difference between the brains of people diagnosed with DID. Brain imaging studies have corroborated the transitions of identity in some DID sufferers. A link between epilepsy and DID has been postulated but this is disputed. Some brain imaging studies have shown differing cerebral blood flow with different alters, and distinct differences overall between subjects with DID and a healthy control group.

A different imaging study showed that findings of smaller hippocampal volumes in patients with a history of exposure to traumatic stress and an accompanying stress-related psychiatric disorder were also demonstrated in DID. This study also found smaller amygdala volumes. Studies have demonstrated various changes in visual parameters between alters. One twin study showed heritable factors were present in DID.

Causes

This disorder is theoretically linked with the interaction of overwhelming stress, traumatic antecedents, insufficient childhood nurturing and the innate ability of children in general to dissociate memories or experiences from consciousness. A high percentage of patients report child abuse others report an early loss, serious medical illness or other traumatic events. People diagnosed with DID often report that they have experienced severe physical and sexual abuse, especially during early to mid childhood. Several psychiatric rating scales of DID sufferers suggested that DID is strongly related to childhood trauma rather than to an underlying electrophysiological dysfunction.

Within the first six years of life young children are still developing a personality structure that allows integrative functioning. Early childhood trauma interferes with the the development of integrative functions (childhood trauma related dissociation). Repeated activation of trauma-related dissociative states (while the myelin in the hippocampus is still being formed) conditions the brain to function state-dependently (dissociative identities).

Others believe that the symptoms of DID are created iatrogenically by therapists using certain treatment techniques with suggestible patients, but this idea is not universally accepted. Skeptics have suggested that a small subset of doctors are responsible for the majority of diagnoses that a small number of therapists were responsible for diagnosing the majority of individuals with DID. Psychologist Nicholas Spanos and others skeptical of the condition have suggested that in addition to iatrogenesis, DID may be the result of role-playing rather than separate personalities, though others disagree, pointing to a lack of incentive to manufacture or maintain separate personalities and point to the claimed histories of abuse of these patients.

Development theory

Severe sexual, physical, or psychological trauma in childhood by a primary caregiver has been proposed as an explanation for the development of DID. In this theory, awareness, memories and feelings of a harmful action or event caused by the caregiver is pushed into the subconscious and dissociation becomes a coping mechanism for the individual during times of stress. These memories and feelings are later experienced as a separate entity, and if this happens multiple times, multiple alters are created.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of dissociative identity disorder is defined by criteria in the American Psychiatric Association's Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM). The DSM-II used the term multiple personality disorder, the DSM-III grouped the diagnosis with the other four major dissociative disorders, and the DSM-IV-TR categorizes it as dissociative identity disorder. Dissociation is recognized as a symptomatic presentation in response to psychological trauma, extreme emotional stress, and, as noted, in association with emotional dysregulation and borderline personality disorder. The ICD-10 continues to list the condition as multiple personality disorder.

The diagnostic criteria in section 300.14 (dissociative disorders) of the DSM-IV require that an adult, for non-physiological reasons, be recurrently controlled by multiple discrete identity or personality states while also suffering extensive memory lapses. While otherwise similar, the diagnostic criteria for children requires also ruling out fantasy. Diagnosis is normally performed by a therapist, psychiatrist or psychologist clinically trained in the specific material who may use specially designed interviews (such as the SCID-D) and personality assessment tools to evaluate a person for a dissociative disorder. The psychiatric history of individuals diagnosed with DID frequently but not always contains multiple previous diagnoses of various mental disorders and treatment failures. Subjectivity in terms like personality, ego-state, identity and amnesia grants a certain degree of subjectivity to diagnosis.

The proposed diagnostic criteria for DID in the DSM-5 is:

- Disruption of identity characterized by two or more distinct personality states (one can be the host) or an experience of possession, as evidenced by discontinuities in sense of self, cognition, behavior, affect, perceptions, and/or memories. This disruption may be observed by others, or reported by the patient.

- Inability to recall important personal information, for everyday events or traumatic events, that is inconsistent with ordinary forgetfulness.

- Causes clinically significant distress and impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning.

- The disturbance is not a normal part of a broadly accepted cultural or religious practice and is not due to the direct physiological effects of a substance (e.g., blackouts or chaotic behavior during alcohol intoxication) or a general medical condition (e.g., complex partial seizures). NOTE: In children, the symptoms are not attributable to imaginary playmates or other fantasy play.

- These specifiers are under consideration.

a) With pseudoseizures or other conversion symptoms b) With somatic symptoms that vary across identities

The proposed Criterion C is intended to "help differentiate normative cultural experiences from psychopathology." This phrase, which occurs in several other diagnostic criteria, is proposed for inclusion in 300.14 as part of a proposed merger of dissociative trance disorder with DID. For example, professionals would be able to take shamanism, which involves voluntary possession trance states, into consideration, and not have to diagnose those who report it as having a mental disorder.

Screening

The SCID-D may be used to make a diagnosis. This interview takes about 30 to 90 minutes depending on the subject's experiences. The Dissociative Disorders Interview Schedule (DDIS) is a highly structured interview that discriminates among various DSM-IV diagnoses. The DDIS can usually be administered in 30–45 minutes. The Dissociative Experiences Scale (DES) is a simple, quick, and validated questionnaire that has been widely used to screen for dissociative symptoms. Tests such as the DES provide a quick method of screening subjects so that the more time-consuming structured clinical interview can be used in the group with high DES scores. Depending on where the cutoff is set, people who would subsequently be diagnosed can be missed. An early recommended cutoff was 15-20. The reliability of the DES in non-clinical samples has been questioned. There is also a DES scale for children and DES scale for adolescents. One study argued that old and new trauma may interact, causing higher DID item test scores.

Differential diagnoses

Conditions which may be present with similar symptoms include borderline personality disorder, and the dissociative conditions of dissociative amnesia and dissociative fugue. The clearest distinction is the lack of discrete formed personalities in these conditions. Malingering may also be considered, and schizophrenia, although those with this last condition will have some form of delusions, hallucinations or thought disorder.

Treatment

Treatment of DID is phase-oriented. The first phase focuses on symptoms and relieving the distressing aspects of the condition and ensuring the safety of the individual. The second phase focuses on stepwise exposure to traumatic memories and prevention of re-dissociation. The third phase focuses on reconnecting the identities of disparate alters into a single functioning identity with all its memories and experiences intact.

Treatment methods may include psychotherapy and medications for comorbid disorders. Some behavior therapists initially use behavioral treatments such as only responding to a single identity, and using more traditional therapy once a consistent response is established.

Brief treatment due to managed care may be difficult, as individuals diagnosed with DID may have unusually difficulties in trusting their therapist or fear rejection and lengthy, regular contact (weekly or biweekly) is more common. Different alters may appear based on their greater ability to deal with specific situational stresses or threats, and some cognitive behavioral therapy strategies involve learning coping strategies other than transitioning between alters. While some patients may initially present with a large number of alters these number of alters may reduce during treatment, though it is considered important for the therapist to become familiar with at lesat the more prominent personality states as the "host" personality may not be the "true" identity of the patient. Specific alters may react negatively to therapy, fearing the therapists goal is to eliminate the alter (particularly those associated with illegal or violence activities). A more appropriate goal of treatment would be to integrate adaptive responses to abuse, injury or other threats into the overall personality structure.

Prognosis

DID does not resolve spontaneously, and symptoms vary over time. Individuals with primarily dissociative symptoms and features of post traumatic stress disorder normally recover with treatment. Those with comorbid addictions, personality, mood, or eating disorders face a longer, slower, and more complicated recovery process. Individuals still attached to abusers face the poorest prognosis; treatment may be long-term and consist solely of symptom relief rather than personality integration. Changes in identity, loss of memory, and awaking in unexplained locations and situations often leads to chaotic personal lives. Individuals with the condition commonly attempt suicide.

Epidemiology

Incidence and prevalence

The DSM does not provide an estimate of incidence; however the number of diagnoses of this condition has risen sharply. A possible explanation for the increase in incidence and prevalence of DID over time is that the condition was misdiagnosed as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or other such disorders in the past; another explanation is that an increase in awareness of DID and child sexual abuse has led to earlier, more accurate diagnosis. Others explain the increase as being due to the use of inappropriate therapeutic techniques in highly suggestible individuals, though this is itself controversial. Figures from psychiatric populations (inpatients and outpatients) show a wide diversity from different countries:

| Country | Prevalence in mentally ill populations | Source study |

|---|---|---|

| India | 0.015% | Chiku et al. (1989) |

| Switzerland | 0.05 - 0.1% | Modestin (1992) |

| China | 0.4% | Xiao et al. (2006) |

| Germany | 0.9% | Gast et al. (2001) |

| Netherlands | 2% | Friedl & Draijer (2000) |

| United States | 10% | Bliss & Jeppsen (1985) |

| United States | 6 - 8% | Ross et al. (1992) |

| United States | 6 - 10% | Foote et al. (2006) |

| Turkey | 14% | Sar et al. (2007) |

| Israel | 0.8% | Ginzburg et al. (2010) |

Figures from the general population show less diversity:

| Country | Prevalence | Source study |

|---|---|---|

| Canada | 1% | Ross (1991) |

| Turkey (male) | 0.4% | Akyuz et al. (1999) |

| Turkey (female) | 1.1% | Sar et al. (2007) |

Comorbidity

Conditions frequently comorbid with DID include:

- bipolar disorder

- major depressive disorder

- posttraumatic stress disorder

- anxiety disorder

- somatization

- personality disorders

- psychotic disorder

In addition, higher incidences of substance abuse and eating disorders are found in individuals with a diagnosis of DID.

History

Before the 19th century, people exhibiting symptoms similar to those were believed to be possessed.

An intense interest in spiritualism, parapsychology, and hypnosis continued throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries, running in parallel with John Locke's views that there was an association of ideas requiring the coexistence of feelings with awareness of the feelings. Hypnosis, which was pioneered in the late 18th century by Franz Mesmer and Armand-Marie Jacques de Chastenet, Marques de Puységur, challenged Locke's association of ideas. Hypnotists reported what they thought were second personalities emerging during hypnosis and wondered how two minds could coexist.

The 19th century saw a number of reported cases of multiple personalities which Rieber estimated would be close to 100. Epilepsy was seen as a factor in some cases, and discussion of this connection continues into the present era.

By the late 19th century there was a general acceptance that emotionally traumatic experiences could cause long-term disorders which might display a variety of symptoms. These conversion disorders were found to occur in even the most resilient individuals, but with profound effect in someone with emotional instability like Louis Vivé (1863-?) who suffered a traumatic experience as a 13 year-old when he encountered a viper. Vivé was the subject of countless medical papers and became the most studied case of dissociation in the 19th century.

Between 1880 and 1920, many great international medical conferences devoted a lot of time to sessions on dissociation. It was in this climate that Jean-Martin Charcot introduced his ideas of the impact of nervous shocks as a cause for a variety of neurological conditions. One of Charcot's students, Pierre Janet, took these ideas and went on to develop his own theories of dissociation. One of the first individuals diagnosed with multiple personalities to be scientifically studied was Clara Norton Fowler, under the pseudonym Christine Beauchamp; American neurologist Morton Prince studied Fowler between 1898 and 1904, describing her case study in his 1906 monograph, Dissociation of a Personality.

In the early 20th century interest in dissociation and multiple personalities waned for a number of reasons. After Charcot's death in 1893, many of his so-called hysterical patients were exposed as frauds, and Janet's association with Charcot tarnished his theories of dissociation. Sigmund Freud recanted his earlier emphasis on dissociation and childhood trauma.

In 1910, Eugen Bleuler introduced the term schizophrenia to replace dementia praecox. A review of the Index medicus from 1903 through 1978 showed a dramatic decline in the number of reports of multiple personality after the diagnosis of schizophrenia became popular, especially in the United States. A number of factors helped create a large climate of skepticism and disbelief; paralleling the increased suspicion of DID was the decline of interest in dissociation as a laboratory and clinical phenomenon.

Starting in about 1927, there was a large increase in the number of reported cases of schizophrenia, which was matched by an equally large decrease in the number of multiple personality reports. Bleuler also included multiple personality in his category of schizophrenia. It was concluded in the 1980s that DID patients are often misdiagnosed as suffering from schizophrenia.

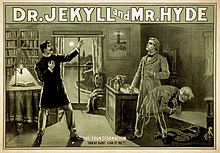

The public, however, was exposed to psychological ideas which took their interest. Mary Shelley's Frankenstein, Robert Louis Stevenson's Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, and many short stories by Edgar Allan Poe had a formidable impact. In 1957, with the publication of the book The Three Faces of Eve and the popular movie which followed it, the American public's interest in multiple personality was revived. During the 1970s an initially small number of clinicians campaigned to have it considered a legitimate diagnosis.

Between 1968 and 1980 the term that was used for dissociative identity disorder was "Hysterical neurosis, dissociative type". The APA wrote: "In the dissociative type, alterations may occur in the patient's state of consciousness or in his identity, to produce such symptoms as amnesia, somnambulism, fugue, and multiple personality." With the publication of the DSM-III, which omitted the terms "hysteria" and "neurosis" (and thus the former categories for dissociative disorders), dissociative diagnoses became "orphans" with their own categories with dissociative identity disorder appearing as "multiple personality disorder". In the opinion of McGill University psychiatrist Joel Paris, this inadvertently legitimized them by forcing textbooks, which mimicked the structure of the DSM, to include a separate chapter on them and resulted in an increase in diagnosis of dissociative conditions. Once a rarely-occurring spontaneous phenomena, became "an artifact of bad (or naïve) psychotherapy" as patients capable of dissociating were accidentally encouraged to express their symptoms by "overly fascinated" therapists. Revision of the third edition of the DSM resulted in the removal of "interpersonality amnesia" as a diagnostic feature of DID, which may have increased the diagnosis of this condition. The fourth edition of the DSM replaced the criteria again and changed the name of the condition from "multiple personality disorder" to the current "dissociative identity disorder" to emphasize the importance of changes to consciousness and identity rather than personality. The inclusion of interperonality amnesia helped to distinguish DID from dissociative disorder not otherwise specified, but the condition retains an inherent subjectivity due to difficulty in defining terms such as personality, identity, ego-state and even amnesia. The ICD-10 still classifies DID as a "Dissociative disorder" and retains the name "multiple personality disorder" with the classification number of F44.8.81.

In 1974 the highly influential book Sybil was published, and later made into a miniseries in 1976 and again in 2007. Describing what Robert Rieber called “the third most famous of multiple personality cases”, it presented a detailed discussion of the problems of treatment of “Sybil”, a pseudonym for Shirley Ardell Mason. Though the book and subsequent films helped popularize the diagnosis, later analysis of the case suggested different interpretations, ranging from Mason’s problems being iatrogenically induced through therapeutic methods or an inadvertent hoax due in part to the lucrative publishing rights, though this conclusions has itself been challenged.

Six years following the publication of Sybil, the diagnosis of multiple personality disorder appeared in the DSM III. As media coverage spiked, diagnoses climbed. There were 200 reported cases of DID as of 1980, and 20,000 from 1980 to 1990. Joan Acocella reports that 40,000 cases were diagnosed from 1985 to 1995.

Society and culture

Main article: Dissociative identity disorder in popular cultureControversy

DID is a controversial diagnosis and condition, with much of the literature on DID still being generated and published in North America, to the extent that it was once regarded as a phenomenon confined to that continent though research has appeared discussing the appearance of DID in other countries and cultures. Among North American psychiatrists there is a lack of consensus regarding the validity of DID. Criticism of the diagnosis continues, with Piper and Merskey describing it as a culture-bound and often iatrogenic condition which they believe is in decline. Proponents believe that the condition is under-diagnosed due to skepticism and lack of awareness from mental health professionals, made difficult due to the lack of specific and reliable criteria for diagnosing DID as well as a lack of prevalence rates due to the failure to examine systematically selected and representative populations.

Psychiatrist Colin A. Ross has stated that based on documents obtained through freedom of information legislation, psychiatrists linked to Project MKULTRA claimed to be able to deliberately induce dissociative identity disorder using a variety of aversive techniques.

Over-representation in North America

In a 1996 review, Joel Paris offered three possible causes for the sudden increase in people diagnosed with DID:

- The result of therapist suggestions to suggestible people, much as Charcot's hysterics acted in accordance with his expectations.

- Psychiatrists' past failure to recognize dissociation being redressed by new training and knowledge.

- Dissociative phenomena are actually increasing, but this increase only represents a new form of an old and protean entity: "hysteria".

Paris believes that the first possible cause is the most likely.

The debate over the validity of this condition, whether as a clinical diagnosis, a symptomatic presentation, a subjective misrepresentation on the part of the patient, or a case of unconscious collusion on the part of the patient and the professional is considerable. There are several main points of disagreement over the diagnosis.

One of the primary reasons for the ongoing recategorization of this condition is that there were once so few documented cases (research in 1944 showed only 76) of what was once referred to as multiple personality.

A 2006 study compared scholarly research and publications on DID and dissociative amnesia to other mental health conditions, such as anorexia nervosa, alcohol abuse and schizophrenia. The results were found to be unusually distributed, with a very low level of publications in the time leading up to the 1980s followed by a significant rise that peaked in the mid-1990s and subsequently rapidly declined in the decade following. Compared to 25 other diagnosis, the mid-90's "bubble" of publications regarding DID was unique. In the opinion of the authors of the review, the publication results suggest a period of "fashion" that waned, and that the two diagnoses " not command widespread scientific acceptance".

See also

- Dissociation

- Dissociative identity disorder in popular culture

- Fugue state

- Identity formation

- Psychogenic amnesia

- Splitting (psychology)

Footnotes

- ^ "Mental Health: Dissociative Identity Disorder (Multiple Personality Disorder)". Webmd.com. Retrieved 2007-12-10.

- Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 15014580 , please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid= 15014580instead. - ^ Sadock 2002, p. 681

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 15503730 , please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid= 15503730instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 9989574 , please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid= 9989574instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 15560314 , please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid= 15560314instead. - ^ Rubin, EH (2005). Adult psychiatry: Blackwell's neurology and psychiatry access series (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons. pp. 280. ISBN 1405117699.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help) - ^ Weiten, W (2010). Psychology: Themes and Variations (8 ed.). Cengage Learning. pp. 461. ISBN 0495813109.

- ^ Paris J (1996). "Review-Essay : Dissociative Symptoms, Dissociative Disorders, and Cultural Psychiatry". Transcult Psychiatry. 33 (1): 55–68. doi:10.1177/136346159603300104.

- ^ Atchison M, McFarlane AC (1994). "A review of dissociation and dissociative disorders". The Australian and New Zealand journal of psychiatry. 28 (4): 591–9. doi:10.3109/00048679409080782. PMID 7794202.

- ^ "Dissociative Identity Disorder". Merck.com. 2010.

- Putnam FW (1984). "The psychophysiologic investigation of multiple personality disorder. A review". Psychiatr. Clin. North Am. 7 (1): 31–9. PMID 6371727.

- Miller SD, Triggiano PJ (1992). "The psychophysiological investigation of multiple personality disorder: review and update". The American journal of clinical hypnosis. 35 (1): 47–61. doi:10.1080/00029157.1992.10402982. PMID 1442640.

- Putnam FW, Zahn TP, Post RM (1990). "Differential autonomic nervous system activity in multiple personality disorder". Psychiatry research. 31 (3): 251–60. doi:10.1016/0165-1781(90)90094-L. PMID 2333357.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Hughes JR, Kuhlman DT, Fichtner CG, Gruenfeld MJ (1990). "Brain mapping in a case of multiple personality". Clinical EEG (electroencephalography). 21 (4): 200–9. PMID 2225470.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Lapointe AR, Crayton JW, DeVito R, Fichtner CG, Konopka LM (2006). "Similar or disparate brain patterns? The intra-personal EEG variability of three women with dissociative identity disorder". Clinical EEG and neuroscience : official journal of the EEG and Clinical Neuroscience Society (ENCS). 37 (3): 235–42. PMID 16929711.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Cocores JA, Bender AL, McBride E (1984). "Multiple personality, seizure disorder, and the electroencephalogram". J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 172 (7): 436–8. doi:10.1097/00005053-198407000-00011. PMID 6427406.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 19553880 , please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=19553880instead. - Coons PM, Milstein V, Marley C (1982). "EEG studies of two multiple personalities and a control". Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 39 (7): 823–5. PMID 7165480.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Psychology Today's Diagnosis Dictionary Dissociative Identity Disorder (Multiple Personality Disorder)". New York, NY: Sussex Publishers LLC. 2005. Archived from the original on 2007-12-29. Retrieved 2008-02-19.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Devinsky O, Putnam F, Grafman J, Bromfield E, Theodore WH (1989). "Dissociative states and epilepsy". Neurology. 39 (6): 835–40. PMID 2725878.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Ross CA; Heber S; Anderson G; et al. (1989). "Differentiating multiple personality disorder and complex partial seizures". General Hospital Psychiatry. 11 (1): 54–8. doi:10.1016/0163-8343(89)90026-1. PMID 2912820.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help) - Reinders AA, Nijenhuis ER, Paans AM, Korf J, Willemsen AT, den Boer JA (2003). "One brain, two selves". Neuroimage. 20 (4): 2119–25. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2003.08.021. PMID 14683715.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Reinders AA; Nijenhuis ER; Quak J; et al. (2006). "Psychobiological characteristics of dissociative identity disorder: A symptom provocation study". Biol. Psychiatry. 60 (7): 730–40. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.12.019. PMID 17008145.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help) - Mathew RJ, Jack RA, West WS (1985). "Regional cerebral blood flow in a patient with split personality". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 142 (4): 504–5. PMID 3976929.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Sar V, Unal SN, Ozturk E (2007). "Frontal and occipital perfusion changes in dissociative identity disorder". Psychiatry Research. 156 (3): 217–23. doi:10.1016/j.pscychresns.2006.12.017. PMID 17961993.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Vermetten E, Schmahl C, Lindner S, Loewenstein RJ, Bremner JD (2006). "Hippocampal and amygdalar volumes in dissociative identity disorder". The American journal of psychiatry. 163 (4): 630–6. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.163.4.630. PMID 16585437.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Miller SD (1989). "Optical differences in cases of multiple personality disorder". J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 177 (8): 480–6. doi:10.1097/00005053-198908000-00005. PMID 2760599.

- Miller SD, Blackburn T, Scholes G, White GL, Mamalis N (1991). "Optical differences in multiple personality disorder. A second look". J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 179 (3): 132–5. doi:10.1097/00005053-199103000-00003. PMID 1997659.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Birnbaum MH, Thomann K (1996). "Visual function in multiple personality disorder". Journal of the American Optometric Association. 67 (6): 327–34. PMID 8888853.

- Jang KL, Paris J, Zweig-Frank H, Livesley WJ (1998). "Twin study of dissociative ~~~~experience". J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 186 (6): 345–51. doi:10.1097/00005053-199806000-00004. PMID 9653418.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Pearson, M.L. (1997). "Childhood trauma, adult trauma, and dissociation" (PDF). Dissociation. 10 (1): 58–62:. Retrieved 2008-06-01.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - "Dissociative Identity Disorder, patient's reference". Merck.com. 2003-02-01. Retrieved 2007-12-07.

- ^ Kluft, RP (2003). "Current Issues in Dissociative Identity Disorder" (PDF). Bridging Eastern and Western Psychiatry. 1 (1): 71–87. Retrieved 2008-05-09.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help) - American Psychiatric Association (2000-06). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders DSM-IV TR (Text Revision). Arlington, VA, USA: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc. p. 943. doi:10.1176/appi.books.9780890423349. ISBN 978-0890420249.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 3418321, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid= 3418321instead. - Putnam, F.W. (1997). Dissociation in children and adolescents: A developmental perspective. New York: Guilford.

- Perry, B.D. (1999). The memory of states: How the brain stores and retrieves traumatic experience. In J. Goodwin & R. Attias (Eds.), Splintered reflections: Images of the body in treatment (pp. 9-38). New York: Basic Books.

- Perry, B.D., Pollard, R.A., Blakely, T.L., Baker, W.L., & Vigilante, D. (1995). Childhood trauma, the neurobiology of adaptation, and "use dependent" development of the brain: How "states" become "traits". Infant Mental Health Journal, 16, 271-291.

- Carson VB (2006). Foundations of Psychiatric Mental Health Nursing: A Clinical Approach (5 ed.). St. Louis: Saunders Elsevier. pp. 266–267. ISBN 1-4160-0088-7.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - American Psychiatric Association (2000-06). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders DSM-IV TR (Text Revision). Arlington, VA, USA: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc. pp. 526–528. doi:10.1176/appi.books.9780890423349. ISBN 978-0890420249.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 7877901, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=7877901instead. - ^ "The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders" (pdf). World Health Organization.

- American Psychiatric Association (2000). "Diagnostic criteria for 300.14 Dissociative Identity Disorder". Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th, text revision (DSM-IV-TR) ed.). ISBN 0-89042-025-4.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 17716088, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid= 17716088instead. - Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 20603761 , please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=20603761instead. - Dissociative identity disorder at the DSM-V showing proposed revision, page found 2011-06-05.

- Dissociative Trance Disorder at the DSM-V showing proposed merger with Dissociative Identity Disorder, page found 2011-06-05.

- Steinberg M, Rounsaville B, Cicchetti DV (1990). "The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R Dissociative Disorders: preliminary report on a new diagnostic instrument". The American journal of psychiatry. 147 (1): 76–82. PMID 2293792.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Ross CA, Ellason JW (2005). "Discriminating among diagnostic categories using the Dissociative Disorders Interview Schedule". Psychological reports. 96 (2): 445–53. doi:10.2466/PR0.96.2.445-453. PMID 15941122.

- Bernstein EM, Putnam FW (1986). "Development, reliability, and validity of a dissociation scale". J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 174 (12): 727–35. doi:10.1097/00005053-198612000-00004. PMID 3783140.

- Carlson EB; Putnam FW; Ross CA; et al. (1993). "Validity of the Dissociative Experiences Scale in screening for multiple personality disorder: a multicenter study". The American journal of psychiatry. 150 (7): 1030–6. PMID 8317572.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help) - Steinberg M, Rounsaville B, Cicchetti D (1991). "Detection of dissociative disorders in psychiatric patients by a screening instrument and a structured diagnostic interview". The American journal of psychiatry. 148 (8): 1050–4. PMID 1853955.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Wright DB, Loftus EF (1999). "Measuring dissociation: comparison of alternative forms of the dissociative experiences scale". The American journal of psychology. 112 (4). The American Journal of Psychology, Vol. 112, No. 4: 497–519. doi:10.2307/1423648. JSTOR 1423648. PMID 10696264. Page 1

- ^ Sadock 2002, p. 683

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 19724751, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid= 19724751instead. - Brown, D., Scheflin, A.W., & Hammond, C.D. (1998). Memory, trauma treatment, and the law. New York: Norton.

- Herman, J.L. (1992). Trauma and recovery. New York: BasicBooks.

- Van der Hart, O., Van der Kolk, B.A., & Boon, S. (1998). Treatment of dissociative disorders. In J.D. Bremner & C.R. Marmar (Eds.), Trauma, memory, and dissociation (pp. 253-283). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press.

- Guidelines for Treating Dissociative Identity Disorder in Adults, Third Revision: Summary Version', Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 12: 2, 188—212 (2011) DOI:10.1080/15299732.2011.537248

- Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 21240739, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid= 21240739instead. - Kohlenberg, R.J. (1991). Functional Analytic Psychotherapy: Creating Intense and Curative Therapeutic Relationships. Springer. ISBN 0306438577.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 18195639 , please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid= 18195639instead. - Boon S, Draijer N (1991). "Diagnosing dissociative disorders in The Netherlands: a pilot study with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R Dissociative Disorders". The American journal of psychiatry. 148 (4): 458–62. PMID 2006691.

- Adityanjee, Raju GS, Khandelwal SK (1989). "Current status of multiple personality disorder in India". The American journal of psychiatry. 146 (12): 1607–10. PMID 2589555.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Modestin J (1992). "Multiple personality disorder in Switzerland". The American journal of psychiatry. 149 (1): 88–92. PMID 1728191.

- Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 16877651, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=16877651instead. - Gast U, Rodewald F, Nickel V, Emrich HM (2001). "Prevalence of dissociative disorders among psychiatric inpatients in a German university clinic". J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 189 (4): 249–57. doi:10.1097/00005053-200104000-00007. PMID 11339321.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Friedl MC, Draijer N (2000). "Dissociative disorders in Dutch psychiatric inpatients". The American journal of psychiatry. 157 (6): 1012–3. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.157.6.1012. PMID 10831486.

- Bliss EL, Jeppsen EA (1985). "Prevalence of multiple personality among inpatients and outpatients". The American journal of psychiatry. 142 (2): 250–1. PMID 3970252.

- Ross CA, Anderson G, Fleisher WP, Norton GR (1992). "Dissociative experiences among psychiatric inpatients". General hospital psychiatry. 14 (5): 350–4. doi:10.1016/0163-8343(92)90071-H. PMID 1521791.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Foote B, Smolin Y, Kaplan M, Legatt ME, Lipschitz D (2006). "Prevalence of dissociative disorders in psychiatric outpatients". The American journal of psychiatry. 163 (4): 623–9. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.163.4.623. PMID 16585436.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Sar V; Koyuncu A; Ozturk E; et al. (2007). "Dissociative disorders in the psychiatric emergency ward". General hospital psychiatry. 29 (1): 45–50. doi:10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2006.10.009. PMID 17189745.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help) - Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 20458202, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid= 20458202instead. - Ross CA (1991). "Epidemiology of multiple personality disorder and dissociation". Psychiatr. Clin. North Am. 14 (3): 503–17. PMID 1946021.

- Akyüz G, Doğan O, Sar V, Yargiç LI, Tutkun H (1999). "Frequency of dissociative identity disorder in the general population in Turkey". Comprehensive psychiatry. 40 (2): 151–9. doi:10.1016/S0010-440X(99)90120-7. PMID 10080263.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Sar V, Akyüz G, Doğan O (2007). "Prevalence of dissociative disorders among women in the general population". Psychiatry Res. 149 (1–3): 169–76. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2006.01.005. PMID 17157389.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 15912905, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid= 15912905instead. - ^ Rieber RW (2002). "The duality of the brain and the multiplicity of minds: can you have it both ways?". History of psychiatry. 13 (49 Pt 1): 3–17. doi:10.1177/0957154X0201304901. PMID 12094818.

- Borch-Jacobsen M, Brick D (2000). "How to predict the past: from trauma to repression". History of Psychiatry. 11 (41 Pt 1): 15–35. doi:10.1177/0957154X0001104102. PMID 11624606.

- ^ Putnam, Frank W. (1989). Diagnosis and Treatment of Multiple Personality Disorder. New York: The Guilford Press. p. 351. ISBN 0-89862-177-1.

- ^ van der Kolk BA, van der Hart O (1989). "Pierre Janet and the breakdown of adaptation in psychological trauma". Am J Psychiatry. 146 (12): 1530–40. PMID 2686473.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Rosenbaum M (1980). "The role of the term schizophrenia in the decline of diagnoses of multiple personality". Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 37 (12): 1383–5. PMID 7004385.

- American Psychiatric Association (1968). "Hysterical Neurosis". Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders second edition. Washington, D.C. p. 40.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Paris, J (2008). Prescriptions for the mind: a critical view of contemporary psychiatry. Oxford University Press. pp. 92. ISBN 0195313836.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 11623821, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid= 11623821instead. - Nathan, D (2011). Sybil Exposed. Free Press. ISBN 978-1439168271.

- Lawrence, M (2008). "Review of Bifurcation of the Self: The history and theory of dissociation and its disorders". American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis. 50 (3): 273–283.

- Adams, C (2003). "Does multiple personality disorder really exist?". The Straight Dope. Retrieved 2008-01-22.

- Acocella, JR (1999). Creating hysteria: Women and multiple personality disorder. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers. ISBN 0-7879-4794-6.

- Trauma And Dissociation in a Cross-cultural Perspective: Not Just a North American Phenomenon. Routledge. 2006. ISBN 978-0-7890-3407-6.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help) - Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 11441778 , please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid= 11441778instead. - Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 19893342 , please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid= 19893342instead. - Ross, C (2000). Bluebird: Deliberate Creation of Multiple Personality Disorder by Psychiatrists. Manitou Communications. ISBN 978-0970452511.

- "Creating Hysteria by Joan Acocella". The New York Times. 1999.

- Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 16361871, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=16361871instead.

References

- Sadock, Benjamin J. (2002). Kaplan and Sadock's Synopsis of Psychiatry: Behavioral Sciences/Clinical Psychiatry (9th ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 0781731836.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link)

Further reading

- Goettmann, B. A. (1994). Multiple personality and dissociation, 1791-1992: a complete bibliography. Lutherville, MD: The Sidran Press. p. 85. ISBN 0-9629164-5-5.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)

External links

| Mental disorders (Classification) | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||