This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Fhjmi54 (talk | contribs) at 09:53, 21 March 2012. The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

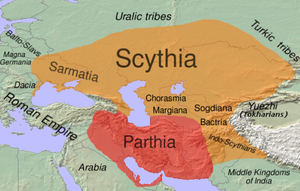

Revision as of 09:53, 21 March 2012 by Fhjmi54 (talk | contribs)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) For other uses, see Saka (disambiguation). Ethnic group Approximate extent of East Iranian languages the 1st century BC is shown in orange. | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| Central Asia Northern India | |

| Languages | |

| Scythian language Sakan language | |

| Religion | |

| Scythian religion | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Indo-Iranians |

The Saka (Old Persian Sakā, Latinized Sacae; Greek Σάκαι; Sanskrit शक ; Chinese 塞; Old Chinese *sək) were a Scythian tribe or group of tribes of Iranian origin.

Greek and Latin texts suggest that the term Scythians referred to a much more widespread grouping of Central Asian peoples.

Classical accounts

Accounts of the Indo-Scythian wars often assume that the Scythian protagonists were a single tribe called the Saka (Sakai or Sakas). But in earlier Greek and Latin texts the term Scythians referred to a much more widespread grouping of Central Asian peoples.

"Scythia" was a generic term loosely applied to a vast area of Central Asia spanning numerous groups and diverse ethnicities. Ptolemy writes that Skuthia was not only "within the Imaos" (the Himalayas) and "beyond the Imaos" (north of the Himalayas), but also speaks of a separate "land of the Sakais" within Scythia. He also notes that the Komedes inhabited "the entire mountainous land of the Sakas".

The Romans recognized both Saceans (Sacae) and Scyths (Scythae).

Isidorus of Charax used the term "Saka" in his work "Parthian stations". They were known to the Chinese as the Sai, as in the Chinese Imperial reports by general Ban Chao. Stephanus of Byzantium referred to the Sakas in Ethnica as Saka sena, or Sakaraucae. He records how the Sakasena, originally Scythians, were pushed west and displaced by the Asii who themselves became known as Scythians as they conquered Sakastan.

To Herodotus (484-425 BC), the Sakai were the 'Amurgioi Skuthai' (i.e. Amyrgians). Strabo suggests that the term Skuthais (Scythians) referred to the Sakai and several other tribes. According to him Bactria was taken by nomads like "the Asioi and the Pasianoi, and the Tacharoi and the Sakaraukai, who originally came from the other side of the Iaxartou river (Syr Darya) that adjoins that of the Sakai and the Sogdoanou and was occupied by the Saki." Arrian refers to the Sakai as Skuthon (a Scythian people) or the Skuthai (the Scythians) who inhabit Asia. The Prologus XLI of Historiae Philippicae also refers to the Scythian invasion of the Greek kingdom of Bactria and Sogdia. The invaders are described as "Sarauceans" (Saraucae) and "Asians" (Asiani).

B. N. Mukerjee has said that it is clear the Greek and Latin scholars cited here believed, all Sakai were Scythians, but not all Scythians were Sakai.

Persian sources

Modern confusion about the identity of the Saka is partly due to the Persians. According to Herodotus, the Persians called all Scythians by the name Sakas. Pliny the Elder (Gaius Plinius Secundus, AD 23–79) provides a more detailed explanation, stating that the Persians gave the name Sakai to the Scythian tribes "nearest to them". The Scythians to the far north of Assyria were also called the Saka suni "Saka or Scythian sons" by the Persians. The Assyrians of the time of Esarhaddon record campaigning against a people they called in the Akkadian the Ashkuza or Ishhuza. Hugo Winckler was the first to associate them with the Scyths which identification remains without serious question. They were closely associated with the Gimirrai, who were the Cimmerians known to the ancient Greeks. Confusion arose because they were known to the Persians as Saka, however they were known to the Babylonians as Gimirrai, and both expressions are used synonymously on the trilingual Behistun inscription, carved in 515 BC on the order of Darius the Great. These Scythians were mainly interested in settling in the kingdom of Urartu, which later became Armenia. The district of Shacusen, Uti Province, reflects their name. In ancient Hebrew texts, the Ashkuz (Ashkenaz) are considered to be a direct offshoot from the Gimirri (Gomer).

Thus the Behistun inscription mentions four divisions of Scythians,

- the Saka paradraya "Scythians beyond the sea" of Sarmatia,

- the Saka tigraxauda "Scythians with pointy hats",

- the Saka haumavarga " haoma-worshipping Scythians" (Amyrgians) of the Pamir and

- the Saka para Sugudam "Scythians beyond Sogdia" at the Jaxartes.

Of these, the Saka tigraxauda were the Saka proper. The Saka paradraya were the western Scythians or Sarmatians, the Saka haumavarga and Saka para Sugudam were likely Scythian tribes associated with or split-of from the original Saka.

Saka in South Asian history

See also: Central Asians in Ancient Indian literaturePliny also mentions Aseni and Asoi clans south of the Hindukush. Bucephala was the capital of the Aseni which stood on the Hydaspes (the Jhelum River). The Sarauceans and Aseni are the Sacarauls and Asioi of Strabo.

The term Asio (or Asii) possibly refers to Horse People and may refer to the Kambojas of the Parama Kamboja domain whose Aswas or horses have been glorified in the Mahabharata as being of excellent quality. Asio, Asi/Asii, Asva/Aswa, Ari-aspi, Aspasios, Aspasii (or Hippasii) are possibly variant names the classical writers have given to the horse-clans of the Kambojas. The Old-Persian words for horse, "asa" and "aspa, have most likely been derived from this."

In the Mahabharata the Rishikas were closely affiliated with the Parama-Kambojas. Similarly, the Pasianois were another Scythian tribe from Central Asia. Saraucae or Sakarauloi obviously refers to the Saka proper from Issyk-kul.

If one accepts this connection, then the Tukharas (= Rishikas = Yuezhi) controlled the eastern parts of Bactria (Chinese Ta-hia) while the combined forces of the Sakarauloi, Asio (horse people = Parama Kambojas) and Pasinoi of Strabo occupied its western parts after being displaced from their original home in the Fergana valley by the Yuezhi. Ta-hia (Daxia) is then taken to mean the Tushara Kingdom which also included Badakshan, Chitral, Kafirstan and Wakhan According to other scholars, it were the Saka hordes alone who had put an end to the Greek kingdom of Bactria.

History

Researchers broadly consider as Saka part of the Scythian culture in Siberia, in particular that of Tasmola and the Upper-Irtysh group. Unlike the Scythians of Europe, Saka remains are wide scattered from Central Asia to Chinese Turkestan and define a set of cultures close to each other but not identical:

- The Zhetysu area of East-Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Ferghana represents Saka culture in the strict sense.

- The Aral-Caspian area relates to the cultures of the Massagetae and Dahae.

- A final Saka area is located in the Tajik and Chinese Pamir.

Recently, bronzes found in Yunnan, China have been tentatively attributed to the Saka.

Migrations of the 2nd and 1st c. BC have left traces in Sogdiana and Bactria, but they cannot firmly be attributed to the Saka, similarly with the sites of Sirkap and Taxila in Pakistan. The rich graves at Tillya Tepe in Afghanistan are seen as part of a population affected by the Saka.

Pazyryk culture

| This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (October 2011) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Some of the first Bronze Age Scythian burials documented by modern archaeologists include the kurgans at Pazyryk in the Ulagan district of the Altai Republic, south of Novosibirsk in the Altai Mountains of southern Siberia. The burial mounds concealed chambers of larch-logs covered over with large cairns of boulders and stones.

Archaeologists have extrapolated the Pazyryk culture from these finds: five large burial mounds and several smaller ones between 1925 and 1949, one opened in 1947 by Russian archaeologist Sergei Rudenko. The Pazyryk culture flourished between the 7th and 3rd century BC in the area associated with the Saka. Burials at Pazyryk in the Altay Mountains have included some spectacularly preserved remains of the "Pazyryk culture" — including the Ice Maiden of the 5th century BC. Women dressed in much the same fashion as men. A Pazyryk burial found in the 1990s contained the skeletons of a man and a woman, each with weapons, arrowheads, and an axe.

Ordinary Pazyryk graves contain only common utensils, but in one, among other treasures, archaeologists found the famous Pazyryk Carpet, the oldest surviving wool-pile oriental rug. Another striking find, a 3-metre-high four-wheel funerary chariot, survived superbly preserved from the 5th century BC.

Migration southward

| This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (October 2011) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

After 178 BC the Saka homeland was invaded from the east by the Yuezhi and Wusun, who were displaced by the rising Xiongnu empire.

Part of the Saka drove over the Pamir to the border area of present-day Afghanistan and Iran (Sistan, before 139 BC) and to the Punjab in north-west India.

In Sakastan they came under the suzerainty of Parthian king Mithridates II (reigned 123-88 BC) with which they allied themselves. They used the Parthian-Roman conflict to their advantage and grabbed much of the Indus Basin and thus the eastern regions from the Indo-Parthians and established a short-lived empire under king Maues, which existed until about 45 AD. They were probably still under Parthian sovereignty, since there are no written records which distinguish the Parthians and Sakas.

Indo-Scythians

Main article: Indo-ScythiansIndo-Scythians is a term used to refer to Saka who migrated into Bactria, Sogdiana, Arachosia, Gandhara, Kashmir, Punjab, Gujarat, Maharashtra and Rajasthan, from the middle of the 2nd century BCE to the 4th century CE.

Indian historians see the actual beginning of the Saka era from 79 AD, after the Kushans conquered the Indo-Parthians and spilled over to the east. The Sakas were once again ousted by the Kushan and forced to wander further into central India. In Rajasthan they came into the Hindu warrior caste of the Kshatriyas and were assimilated and were now feared nomadic warriors and rulers, for which Rajasthan was famous for a long time.

Under the so-called Kshatrya kings the Shaka Ujjayini ruled from parts of north west India and presented, for example, under Rudradaman I (r. about 130-150), a competition to the Satavahana dynasty. They were initially dependent on the Kushan. The Kshatriya kingdom was apparently after 397 conquered by king Chandragupta II (reigned 375-413/15).

Kingdom of Khotan

Main article: Kingdom of KhotanIn the 3rd century AD the Saka had their own kingdom in Khotan.

Language

The language of the original Saka tribes is unknown. The only record from their early history is the Issyk inscription, a short fragment on a silver cup found in the Issyk kurgan.

The inscription is in a variant of the Kharoṣṭhī script, and is probably in a Saka dialect, constituting one of very few autochthonous epigraphic traces of that language. Harmatta (1999) identifies the language as Khotanese Saka, tentatively translating "The vessel should hold wine of grapes, added cooked food, so much, to the mortal, then added cooked fresh butter on".

What is nowadays called the Saka language is the language of the kingdom of Khotan which was ruled by the Saka. This was gradually conquered and acculturated by the Turkic expansion to Central Asia beginning in the 4th century. The only known remnants of the Khotanese Saka language come from Xinjiang, China, but the language there is widely divergent from the rest of Iranian and accordingly is called eastern or northeastern Iranian. It also is divided into two divergent dialects.

Notes

- P. Lurje, “Yārkand”, Encyclopædia Iranica, online edition

- Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society ... - Google Books. 2007-04-06. Retrieved 2010-12-30.

- Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain & Ireland By Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland-page-323

- Geography VI, 12, 1f; VI, 13; 1f, VI, 15, 1f

- History, VII, 64

- Strabo, XI, 8, 2

- (Lucius Flavius Arrianus 'Xenophon' , c AD 92-175)

- Ambaseos Alexandrou, III, 8, 3

- B. N. Mukerjee, Political History of Ancient India, 1996, p 690-91.

- Herodotus Book VII, 64

- Naturalis Historia, VI, 19, 50

- ^ Westermann, Claus (1984). : A Continental Commentary. Minneapolis. p. 506. ISBN 080069500.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: length (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|unused_data=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - George Rawlinson, noted in his translation of History of Herodotus, Book VII, p. 378

- Kurkjian, Vahan M. (1964). A History of Armenia. New York: Armenian General Benevolent Union of America. p. 23.

- "The sons of Gomer were Ashkenaz, Riphath, and Togarmah." See also the entry for Ashkenaz in Young, Robert. Analytical Concordance to the Bible. McLean, Virginia: Mac Donald Publishing Company. ISBN 0917006291.

- Pliny: Hist Nat., VI.21.8-23.11, List of Indian races

- Alexander the Great, Sources and Studies, p 236, W. W. Tarn; Political History of Indian People, 1996, p 232, H. C. Raychaudhury, B. N. Mukerjee

- History and Culture of Indian People, Age of Imperial Unity, p 111; Political History of Ancient India, 1996, p 692.

- For nomenclature Aspasii, Hipasii, see: Olaf Caroe, The Pathans, 1958, pp 37, 55-56. Pliny also refers to horse clans like Aseni, Asoi living in north-west of India (which were none-else than the Ashvayana and Ashvakayana Kambojas of Indian texts). See: Hist. Nat. VI 21.8-23.11; See Ancient India as Described by Megasthenes and Arrian, Trans. and edited by J. W. McCrindle, Calcutta and Bombay,: Thacker, Spink, 1877, 30-174.

- Encyclopedia Iranica Article on Asb

- Lohan. ParamaKambojan.Rishikan.uttaranapi:MBH 2.27.25; Kambojarishika ye cha MBH 5.5.15 etc.

- Political History of Ancient India, 1996, Commentary, p 719, B. N. Mukerjee. Cf: "It appears likely that like the Yue-chis, the Scythians had also occupied a part of Transoxiana before conquering Bactria. If the Tokhario, who were the same as or affiliated with Yue-chihs, and who were mistaken as Scythian people, particiapated in the same series of invasions of Bactria of the Greeks, then it may be inferred that eastern Bactria was conquered by Yue-chis and the western by other nomadic people in about the same period. In other words, the Greek rule in Bactria was put to end in c 130/29 BC due to invasion by the Great Yue-chis and the Scythians Sakas nomads (Commentary: Political History of Ancient India, 1996, p 692-93, B.N. Mukerjee). It is notable that before its occupation by Tukhara Yue-chis, Badakashan formed a part of ancient Kamboja i.e. Parama Kamboja country. But after its occupation by the Tukharas in second century BC, it became a part of Tukharistan. Around 4th-5th century, when the fortunes of the Tukharas finally died down, the original population of Kambojas re-asserted itself and the region again started to be called by its ancient name Kamboja (See: Bhartya Itihaas ki Ruprekha, p 534, J.C. Vidyalankar; Ancient Kamboja, People and the Country, 1981, pp 129, 300 J.L. Kamboj; Kambojas Through the Ages, 2005, p 159, S Kirpal Singh). There are several later-time references to this Kamboja of Pamirs/Badakshan. Raghuvamsha, a 5th c Sanskrit play by Kalidasa, attests their presence on river Vamkshu (Oxus) as neighbors to the Hunas (4.68-70). They have also been attested as Kiumito by 7th c Chinese pilgrim Hiun Tsang. Eighth century king of Kashmir, king Lalitadiya had invaded the Oxian Kambojas as is attested by Rajatarangini of Kalhana (See: Rajatarangini 4.163-65). Here they are mentioned as living in the eastern parts of the Oxus valley as neighbors to the Tukharas who were living in western parts of Oxus valley (See: The Land of the Kambojas, Purana, Vol V, No, July 1962, p 250, D. C. Sircar). These Kambojas apparently were descendants of that section of the Kambojas who, instead of leaving their ancestral land during second c BC under assault from Ta Yue-chi, had compromised with the invaders and had decided to stay put in their ancestral land instead of moving to Helmond valley or to the Kabol valley. There are other references which equate Kamboja= Tokhara. A Buddhist Sanskrit Vinaya text (N. Dutt, Gilgit Manuscripts, III, 3, 136, quoted in B.S.O.A.S XIII, 404) has the expression satam Kambojikanam kanayanam i.e a hundred maidens from Kamboja. This has been rendered in Tibetan as Tho-gar yul-gyi bu-mo brgya and in Mongolian as Togar ulus-un yagun ükin. Thus Kamboja has been rendered as Tho-gar or Togar. And Tho-gar/Togar is Tibetan/Mongolian names for Tokhar/Tukhar. See refs: Irano-Indica III, H. W. Bailey, Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, Vol. 13, No. 2, 1950, pp. 389-409; see also: Ancient Kamboja, Iran and Islam, 1971, p 66, H. W. Bailey.

- Cambridge History of India, Vol I, p 510; Taxila, Vol I, p 24, Marshal, Early History of North India, p 50, S. Chattopadhyava.

- Yaroslav Lebedynsky, P. 84

References

- Bailey, H. W. 1958. "Languages of the Saka." Handbuch der Orientalistik, I. Abt., 4. Bd., I. Absch., Leiden-Köln. 1958.

- Bailey, H. W. (1979). Dictionary of Khotan Saka. Cambridge University Press. 1979. 1st Paperback edition 2010. ISBN 978-0-521-14250-2.

- Davis-Kimball, Jeannine. 2002. Warrior Women: An Archaeologist's Search for History's Hidden Heroines. Warner Books, New York. 1st Trade printing, 2003. ISBN 0-446-67983-6 (pbk).

- Bulletin of the Asia Institute: The Archaeology and Art of Central Asia. Studies From the Former Soviet Union. New Series. Edited by B. A. Litvinskii and Carol Altman Bromberg. Translation directed by Mary Fleming Zirin. Vol. 8, (1994), pp. 37–46.

- Hill, John E. (2009) Through the Jade Gate to Rome: A Study of the Silk Routes during the Later Han Dynasty, 1st to 2nd Centuries CE. John E. Hill. BookSurge, Charleston, South Carolina. ISBN 978-1-4392-2134-1.

- Hill, John E. 2004. The Peoples of the West from the Weilue 魏略 by Yu Huan 魚豢: A Third Century Chinese Account Composed between 239 and 265 CE. Draft annotated English translation.

- Lebedynsky, Iaroslav. (2006). Les Saces: Les <<Scythes>> d'Asie, VIII av. J.-C.-IV siècle apr. J.-C. Editions Errance, Paris. ISBN 2-87772-337-2 (in French).

- Pulleyblank, Edwin G. 1970. "The Wu-sun and Sakas and the Yüeh-chih Migration." Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 33 (1970), pp. 154–160.

- Puri, B. N. 1994. "The Sakas and Indo-Parthians." In: History of civilizations of Central Asia, Volume II. The development of sedentary and nomadic civilizations: 700 B.C. to A.D. 250. Harmatta, János, ed., 1994. Paris: UNESCO Publishing, pp. 191–207.

- Thomas, F. W. 1906. "Sakastana." Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society (1906), pp. 181–216.

- Yu, Taishan. 1998. A Study of Saka History. Sino-Platonic Papers No. 80. July, 1998. Dept. of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies, University of Pennsylvania.

- Yu, Taishan. 2000. A Hypothesis about the Source of the Sai Tribes. Sino-Platonic Papers No. 106. September, 2000. Dept. of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies, University of Pennsylvania.

External links

- Scythians/Sacae: Article by Jona Lendering

- Article by Kivisild et al. on genetic heritage of early Indian settlers

- Indian, Japanese and Chinese Emperors

| ||

|---|---|---|

|  | |

| See also Taxation districts of the Achaemenid Empire (according to Herodotus) | ||