This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Esperant (talk | contribs) at 17:13, 15 April 2006 (→Marx's influence). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

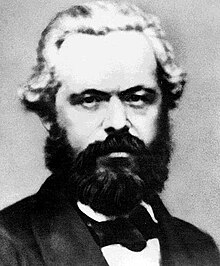

Revision as of 17:13, 15 April 2006 by Esperant (talk | contribs) (→Marx's influence)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) "Marx" redirects here. For other uses, see Marx (disambiguation).| Karl Marx | |

|---|---|

| Era | 19th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western Philosophers |

| School | Founder of Marxism |

| Main interests | Politics, Economics, class struggle |

| Notable ideas | Co-founder of Marxism (with Engels), alienation and exploitation of the worker, The Communist Manifesto, Das Kapital |

Karl Heinrich Marx (May 5, 1818 Trier, Germany – March 14, 1883 London) was an immensely influential German philosopher, political economist, and revolutionary. While Marx addressed a wide range of issues, he is most famous for his analysis of history in terms of class struggles, summed up in the opening line of the introduction to the Communist Manifesto: "The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggle." While Marx was a relatively obscure figure in his own lifetime, his ideas began to exert a major influence on workers' movements shortly after his death. This influence was given added impetus by the victory of the Marxist Bolsheviks in the Russian Revolution, and there are few parts of the world which were not significantly touched by Marxian ideas in the course of the twentieth century. The relation of Marx's own thought to the popular, "Marxist" interpretations of it during this period is a point of controversy. While Marx's ideas have declined somewhat in popularity, particularly with the decline of Marxism in Russia, they are still very influential today, both in academic circles, and in political practice, and Marxism continues to be the official ideology of numerous states and political movements.

Biography

Childhood

Karl Marx was born into a progressive and wealthy Jewish family in Trier, in the Rhineland region of Germany. His father Heinrich, who had descended from a long line of rabbis, converted to Christianity, despite his many deistic tendencies. Marx's father was actually born Herschel Mordechai, but when the Prussian authorities would not allow him to continue practicing law as a Jew, he joined the official denomination of the Prussian state, Lutheranism, which accorded him advantages, as one of a small minority of Lutherans in a predominantly Roman Catholic region. The Marx household hosted many visiting intellectuals and artists during Karl's early life.

Education

After graduating from the Trier gymnasium (school), Marx enrolled in the University of Bonn in 1835 at the age of 17 to study law, where he joined the Trier Tavern Club drinking society and at one point served as its president; his grades suffered as a result. Marx was interested in studying philosophy and literature, but his father would not allow it because he did not believe that Karl would be able to comfortably support himself in the future as a scholar. The following year, his father forced him to transfer to the far more serious and academically oriented Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität in Berlin. During this period, Marx wrote many poems and essays concerning life, using the theological language acquired from his liberal, deistic father, such as "the Deity," but also absorbed the atheistic philosophy of the left-Hegelians who were prominent in Berlin at the time. Marx earned a doctorate in 1841 with a thesis titled The Difference Between the Democritean and Epicurean Philosophy of Nature.

Marx and the Young Hegelians

For the so-called left-Hegelians, Hegel's dialectical method, separated from its theological content, provided a powerful weapon for the critique of established religion and politics. Some members of this circle drew an analogy between post-Aristotelian philosophy and post-Hegelian philosophy. Another Young Hegelian, Max Stirner, applied Hegelian criticism and argued that stopping anywhere short of nihilistic egoism was mysticism. His views were not accepted by most of his colleagues; nevertheless, Stirner's book was the main reason Marx abandoned Feuerbachian materialism and developed the basic concept of historical materialism. One of Marx's teachers was Baron von Westphalen, father of Jenny von Westphalen, whom Karl Marx later married.

Activities in Europe

When his mentor, Bruno Bauer, was dismissed from Friedrich-Wilhelms' philosophy faculty in 1842, Marx abandoned academia and moved into journalism. In October of 1842, he became editor of the influential liberal newspaper Rheinische Zeitung (literally "Rhenish Newspaper") located in Cologne, Germany. The newspaper was shut down in 1843 by the Prussian government, in part due to Marx's conflicts with government censors. Marx continued his writing as a freelance journalist, but his radical political views meant that he had to leave Germany.

Marx left for France, where he re-evaluated his relationship with Bauer and the Young Hegelians, and wrote On the Jewish Question, mostly a critique of current notions of civil rights and political emancipation, which also includes several critical references to Judaism and Jewish culture from an atheistic standpoint. It was in Paris that he met and began working with his life-long collaborator Friedrich Engels, a committed communist, who kindled Marx's interest in the situation of the working class and guided Marx's interest in economics. Marx became a communist and set down his views in a series of writings known as the Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts of 1844, which remained unpublished until the 1930s. In the Manuscripts, Marx outlined a humanist conception of communism, influenced by the philosophy of Ludwig Feuerbach and based on a contrast between the alienated nature of labor under capitalism and a communist society in which human beings freely developed their nature in cooperative production. After they were forced to leave Paris in turn because of his politics, Marx and Engels moved to Brussels, Belgium.

There Marx devoted himself to an intensive study of history and elaborated what came to be known as the historical materialism, particularly in a manuscript (published posthumously as The German Ideology), the basic thesis of which was that "the nature of individuals depends on the material conditions determining their production." Marx traced the history of the various modes of production and predicted the collapse of the present one -- industrial capitalism -- and its replacement by communism.

Next, Marx wrote The Poverty of Philosophy (1847), a response to Pierre-Joseph Proudhon's The Philosophy of Poverty and a critique of French socialist thought. These works laid the foundation for Marx and Engels' most famous work, The Communist Manifesto, first published on February 21, 1848, as the maifesto of the Communist League, a small group of European communists who had fallen under Marx and Engels' influence.

Later that year, Europe experienced tremendous revolutionary upheaval. Marx was arrested and expelled from Belgium; in the meantime a working-class movement had seized power from King Louis Philippe in France, and invited Marx to return to Paris, where he witnessed the revolutionary Paris Commune first hand.

When this collapsed in 1849, Marx moved back to Cologne and started the Neue Rheinische Zeitung ("New Rhenish Newspaper"). During its existence he was put on trial twice, on February 7, 1849 because of a press misdemeanour, and on the 8th charged with incitement to armed rebellion. Both times he was acquitted. The paper was soon suppressed and Marx returned to Paris, but was forced out again. This time he sought refuge in London in May 1849 where he was to remain for the rest of his life.

London

Settling in London, Marx was optimistic about the imminence of a new revolutionary outbreak in Europe. He rejoined the Communist League and wrote two lengthy pamphlets on the 1848 revolution in France and its aftermath, The Class Struggles in France and The 18th Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte. He was soon convinced that "a new revolution is possible only in consequence of a new crisis" and then devoted himself to the study of political economy in order to determine the causes and conditions of this crisis.

Marx's major work on political economy made slow progress. By 1857 he had produced a gigantic 800 page manuscript on capital, landed property, wage labor, the state, foreign trade and the world market. This work however was not published until 1941, under the title Grundrisse. In the early 1860s worked on composing three large volumes, Theories of Surplus Value, which discussed the theoreticians of political economy, particularly Adam Smith and David Ricardo. During this period, Marx championed the Union cause in the United States Civil War. In 1867, well behind schedule, the first volume of Capital was published, a work which analyzed the capitalist process of production. Here, Marx elaborated his labor theory of value and his conception of surplus value and exploitation which he argued would ultimately lead to a falling rate of profit and the collapse of industrial capitalism. Volumes II and III remained mere manuscripts upon which Marx continued to work for the rest of his life and were published posthumously by Engels.

One reason why Marx was so slow to publish Capital was that he was devoting his time and energy to the First International, to whose General Council he was elected at its inception in 1864. He was particularly active in preparing for the annual Congresses of the International and leading the struggle against the anarchist wing led by Mikhail Bakunin (1814-1876). Although Marx won this contest, the transfer of the seat of the General Council from London to New York in 1872, which Marx supported, led to the decline of the International. The most important political event during the existence of the International was the Paris Commune of 1871 when the citizens of Paris rebelled against their government and held the city for two months. On the bloody suppression of this rebellion, Marx wrote one of his most famous pamphlets, The Civil War in France, an enthusiastic defense of the Commune.

During the last decade of his life, Marx's health declined and he was incapable of the sustained effort that had characterized his previous work. He did manage to comment substantially on contemporary politics, particularly in Germany and Russia. In Germany, in his Critique of the Gotha Programme, he opposed the tendency of his followers Karl Liebknecht (1826-1900) and August Bebel (1840-1913) to compromise with the state socialism of Lasalle in the interests of a united socialist party. In his correspondence with Vera Zasulich, Marx contemplated the possibility of Russia's bypassing the capitalist stage of development and building communism on the basis of the common ownership of land characteristic of the village mir.

Family life

Karl Marx's engagement to Jenny von Westphalen, an aristocrat, was kept secret at first, and for several years was opposed by both the Marxes and Westphalens. Karl and Jenny stayed in touch throughout the first half of his life, when he was moving around Europe.

During the first half of the 1850s the Marx family lived in poverty in a three room flat in the Soho quarter of London. Marx and Jenny already had four children and two more were to follow. Of these only three survived. Marx's major source of income at this time was Engels who was drawing a steadily increasing income from the family business in Manchester. This was supplemented by weekly articles written as a foreign correspondent for the New York Daily Tribune. Money from Engels allowed the family to move to somewhat more salubrious lodging in a new suburb on the then-outskirts of London. Marx generally lived a hand-to-mouth existence, forever at the limits of his resources, although it is worth noting that this did extend to some spending on relatively bougeois luxuries, which he felt were necessities for his wife and children given their social status and the mores of the time.

There is a disputed rumour that Marx was the father of Frederick Demuth, the son of Marx's housekeeper, Lenchen Demuth. The rumour lacks any direct corroboration.

Death and Legacy

Following the death of his wife Jenny in 1881, Marx's health worsened and he died in 1883. He is buried in Highgate Cemetery, London. The message carved on Marx's tombstone is: "WORKERS OF ALL LANDS, UNITE", the final line of The Communist Manifesto. The tombstone was a monument built in 1954 by the Communist Party of Great Britain - Marx's original tomb was humbly adorned; only eleven people were present at his funeral.

Several of Marx's closest friends spoke at his funeral, including Friedrich Engels, who delivered the following eulogy:

- On the 14th of March, at a quarter to three in the afternoon, the greatest living thinker ceased to think. He had been left alone for scarcely two minutes, and when we came back we found him in his armchair, peacefully gone to sleep-but forever.

- …

- His name will endure through the ages, and so also will his work!

Marx's daughter Eleanor (1855-1898) became a socialist like her father and helped edit his works.

Marx's thought

As the American Marx scholar Hal Draper remarked, "there are few thinkers in modern history whose thought has been so badly misrepresented, by Marxists and anti-Marxists alike." The legacy of Marx's thought is bitterly contested between numerous tendencies who claim to be Marx's most accurate interpreters, including Marxist-Leninism, Trotskyism and libertarian Marxism.

Philosophy

Marx's analysis of history is based on his distinction between the means of production, literally those things, such as land, natural resources, and technology, that are necessary for the production of material goods, and the relations of production, in other words, the social and technical relationships people enter into as they acquire and use the means of production. Together these comprise the mode of production; Marx observed that within any given society the mode of production changes, and that European societies had progressed from a feudal mode of production to a capitalist mode of production. In general, Marx believed that the means of production change more rapidly than the relations of production (for example, we develop a new technology, such as the internet, and only later do we develop laws to regulate that technology). For Marx this mismatch between (economic) base and (social) superstructure is a major source of social disruption and conflict.

Marx understood the "social relations of production" to comprise not only relations among individuals, but between or among groups of people, or classes. Marx sought to define classes in terms of objective criteria, namely their relation to the means of production. For Marx, different classes have divergent interests, which is another source of social disruption and conflict. Conflict between social classes being something which is inherent in all human history:

- The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles. (The Communist Manifesto, Chap. 1)

Marx was especially concerned with how people relate to that most fundamental resource of all, their own labour-power. The notion of labour is fundamental in Marx's thought. Basically, Marx argued that it is human nature to transform nature, and he calls this process of transformation "labour" and the capacity to transform nature labour power.

For Marx, this is a natural capacity for a physical activity, but it is intimately tied to the human mind and human imagination: Marx wrote extensively about this in terms of the problem of alienation. As with the dialectic, Marx began with a Hegelian notion of alienation but developed a more materialist conception. For Marx, the possibility that one may give up ownership of one's own labour — one's capacity to transform the world — is tantamount to being alienated from one's own nature. Marx described this loss in terms of commodity fetishism, in which the things that people produce, commodities, appear to have a life and movement of their own to which humans and their behavior merely adapt. This disguises the fact that the exchange and circulation of commodities really are the product and reflection of social relationships among people. Under capitalism, social relationships of production, such as among workers or between workers and capitalists, are mediated through commodities, including labor, that are bought and sold on the market. It should however be noted that some, most notably Louis Althusser, have denied that these views of the "Young Marx" are truly compatible with his later work.

Commodity fetishism is an example of what Engels called false consciousness, which is closely related to bourgeois ideology, the ideology which reflects the interests of the capitalist class, but which is presented as universal and eternal. Put another way, the control that one class exercises over the means of production includes not only the production of food or manufactured goods; it includes the production of ideas as well (this provides one possible explanation for why members of a subordinate class may hold ideas contrary to their own interests). Thus, while such ideas may be false, they also reveal in coded form some truth about political relations. For example, although the belief that the things people produce are actually more productive than the people who produce them is literally absurd, it does reflect the fact (according to Marx and Engels) that people under capitalism are alienated from their own labour-power. Another example of this sort of analysis is Marx's understanding of religion, summed up in a passage from the preface to his 1843 Contribution to the Critique of Hegel's Philosophy of Right:

- Religious suffering is, at one and the same time, the expression of real suffering and a protest against real suffering. Religion is the sigh of the oppressed creature, the heart of a heartless world, and the soul of soulless conditions. It is the opium of the people.

Political economy

Marx argued that this alienation of human work (and resulting commodity fetishism) is precisely the defining feature of capitalism. Prior to capitalism, markets existed in Europe where producers and merchants bought and sold commodities. According to Marx, a capitalist mode of production developed in Europe when labor itself became a commodity — when peasants became free to sell their own labor-power, and needed to do so because they no longer possessed their own land. People sell their labor-power when they accept compensation in return for whatever work they do in a given period of time (in other words, they are not selling the product of their labor, but their capacity to work). In return for selling their labor power they receive money, which allows them to survive. Those who must sell their labor power are "proletarians." The person who buys the labor power, generally someone who does own the land and technology to produce, is a "capitalist" or "bourgeois." The proletarians inevitably outnumber the capitalists.

Marx distinguished industrial capitalists from merchant capitalists. Merchants buy goods in one market and sell them in another. Since the laws of supply and demand operate within given markets, there is often a difference between the price of a commodity in one market and another. Merchants, then, practice arbitrage, and hope to capture the difference between these two markets. According to Marx, capitalists, on the other hand, take advantage of the difference between the labor market and the market for whatever commodity is produced by the capitalist. Marx observed that in practically every successful industry input unit-costs are lower than output unit-prices. Marx called the difference "surplus value" and argued that this surplus value had its source in surplus labour, the difference between what it costs to keep workers alive and what they can produce.

The capitalist mode of production is capable of tremendous growth because the capitalist can, and has an incentive to, reinvest profits in new technologies. Marx considered the capitalist class to be the most revolutionary in history, because it constantly revolutionized the means of production. But Marx argued that capitalism was prone to periodic crises. He suggested that over time, capitalists would invest more and more in new technologies, and less and less in labor. Since Marx believed that surplus value appropriated from labor is the source of profits, he concluded that the rate of profit would fall even as the economy grew. When the rate of profit falls below a certain point, the result would be a recession or depression in which certain sectors of the economy would collapse. Marx understood that during such a crisis the price of labor would also fall, and eventually make possible the investment in new technologies and the growth of new sectors of the economy.

Marx believed that this cycle of growth, collapse, and growth would be punctuated by increasingly severe crises. Moreover, he believed that the long-term consequence of this process was necessarily the enrichment and empowerment of the capitalist class and the impoverishment of the proletariat. He believed that were the proletariat to seize the means of production, they would encourage social relations that would benefit everyone equally, and a system of production less vulnerable to periodic crises. In general, Marx thought that peaceful negotiation of this problem was impracticable, and that a massive, well-organized and violent revolution would in general be required, because the ruling class would not give up power without violence. He theorized that to establish the socialist system, a dictatorship of the proletariat - a period where the needs of the working-class, not of capital, will be the common deciding factor - must be created on a temporary basis. As he wrote in his "Critique of the Gotha Program", "between capitalist and communist society there lies the period of the revolutionary transformation of the one into the other. Corresponding to this is also a political transition period in which the state can be nothing but the revolutionary dictatorship of the proletariat."

Influences on Marx's thought

Marx's thought was strongly influenced by:

- The dialectical method and historical orientation of Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel;

- The classical political economy of Adam Smith and David Ricardo;

- French socialist and sociological thought, in particular the thought of Jean-Jacques Rousseau;

- Earlier German materialism, particularly Ludwig Feuerbach.

Marx believed that he could study history and society scientifically and discern tendencies of history and the resulting outcome of social conflicts. Some followers of Marx concluded, therefore, that a communist revolution is inevitable. However, Marx famously asserted in the eleventh of his Theses on Feuerbach that "philosophers have only interpreted the world, in various ways; the point however is to change it", and he clearly dedicated himself to trying to alter the world. Consequently, most followers of Marx are not fatalists, but activists who believe that revolutionaries must organize social change.

Marx's view of history, which came to be called historical materialism (and which was developed further as the philosophy of dialectical materialism) is certainly influenced by Hegel's claim that reality (and history) should be viewed dialectically. Hegel believed that the direction of human history is characterized in the movement from the fragmentary toward the complete and the real (which was also a movement towards greater and greater rationality). Sometimes, Hegel explained, this progressive unfolding of the Absolute involves gradual, evolutionary accretion but at other times requires discontinuous, revolutionary leaps — episodal upheavals against the existing status quo. For example, Hegel strongly opposed slavery in the United States during his lifetime, and he envisioned a time when Christian nations would radically eliminate it from their civilization. While Marx accepted this broad conception of history, Hegel was an idealist, and Marx sought to rewrite dialectics in materialist terms. He wrote that Hegelianism stood the movement of reality on its head, and that it was necessary to set it upon its feet.

Marx's acceptance of this notion of materialist dialectics which rejected Hegel's idealism was greatly influenced by Ludwig Feuerbach. In The Essence of Christianity, Feuerbach argued that God is really a creation of man and that the qualities people attribute to God are really qualities of humanity. Accordingly, Marx argued that it is the material world that is real and that our ideas of it are consequences, not causes, of the world. Thus, like Hegel and other philosophers, Marx distinguished between appearances and reality. But he did not believe that the material world hides from us the "real" world of the ideal; on the contrary, he thought that historically and socially specific ideology prevented people from seeing the material conditions of their lives clearly.

The other important contribution to Marx's revision of Hegelianism was Engels' book, The Condition of the Working Class in England in 1844, which led Marx to conceive of the historical dialectic in terms of class conflict and to see the modern working class as the most progressive force for revolution.

Marx's influence

See also: Marxism

Marx and Engels' work covers a wide range of topics and presents a complex analysis of history and society in terms of class relations. Followers of Marx and Engels have drawn on this work to propose a grand, cohesive theoretical outlook dubbed Marxism. Nevertheless, there have been numerous debates among Marxists over how to interpret Marx's writings and how to apply his concepts to current events and conditions. Moreover, it is important to distinguish between "Marxism" and "what Marx believed"; for example, shortly before he died in 1883, Marx wrote a letter to the French workers' leader Jules Guesde, and to his own son-in-law Paul Lafargue, accusing them of "revolutionary phrase-mongering" and of denying the value of reformist struggles; "if that is Marxism" — paraphrasing what Marx wrote — "then I am not a Marxist").

Essentially, people use the word "Marxist" to describe those who rely on Marx's conceptual language (e.g. "mode of production", "class", "commodity fetishism") to understand capitalist and other societies, or to describe those who believe that a workers' revolution as the only means to a communist society. The clash between Marx's own theoretical framework and the umbrella term "Marxist" is often misconstrued, a prime example being the bias placed against studying Marx’s writings during the Cold War period in American academic institutions. Some, particularly in academic circles, who accept much of Marx's theory, but not all its implications, call themselves "Marxian" instead.

Six years after Marx's death, Engels and others founded the "Second International" as a base for continued political activism. This organization was far more successful than the First International had been, containing mass workers' parties, particularly the large and successful German Social Democratic Party, which was predominantly MArxist in outlook. This international collapsed in 1914, however, in part because some members turned to Edward Bernstein's "evolutionary" socialism, and in part because of divisions precipitated by World War I.

World War I also led to the Russian Revolution in which a left splinter of the Second International, the Bolsheviks, led by Vladimir Lenin, took power. The revolution dynamized workers around the world into setting up their own section of the Bolsheviks' "Third International". Lenin claimed to be both the philosophical and political heir to Marx, and developed a political program, called "Leninism" or "Bolshevism", which called for revolution organized and led by a centrally organized "Communist Party."

Marx believed that the communist revolution would take place in advanced industrial societies such as France, Germany and England, but Lenin argued that in the age of imperialism, and due to the "law of uneven development", where Russia had on the one hand, an antiquated agricultural society, but on the other hand, some of the most up-to-date industrial concerns, the "chain" might break at its weakest points, that is, in the so-called "backward" countries.

In China Mao Zedong also claimed to be an heir to Marx, but argued that peasants and not just workers could play a leading role in a Communist revolution. This was a departure from Marx and Lenin's view of revolution, which maintained that the proletariat must have the leading role. Marxism-Leninism as espoused by Mao came to be internationally known as Maoism.

Under Lenin, and increasingly after the rise to power of Joseph Stalin, the actions of the Soviet Union (and later of the People's Republic of China) came in many people's mind to be synonymous with Marxism, with its attendant suppression of the rights of individuals and workers in the name of the struggle against capitalism, including the execution of larges numbers of people under Stalin, a fact which has been exploited for propaganda purposes by anti-Communists. However, there were throughout dissenting Marxist voices — Marxists of the old school of the Second International, the left communists who split off from the Third International shortly after its formation, and later Leon Trotsky and his followers, who set up a "Fourth International" in 1938 to compete with that of Stalin, claiming to represent true Bolshevism.

Coming from the Second International milieu, in the 1920s and '30s, a group of dissident Marxists founded the Institute for Social Research in Germany, among them Max Horkheimer, Theodor Adorno, Erich Fromm, and Herbert Marcuse. As a group, these authors are often called the Frankfurt School. Their work is known as Critical Theory, a type of Marxist philosophy and cultural criticism heavily influenced by Hegel, Freud, Nietzsche, and Max Weber.

The Frankfurt School broke with earlier Marxists, including Lenin and Bolshevism in several key ways. First, writing at the time of the ascendance of Stalinism and fascism, they had grave doubts as to the traditional Marxist concept of proletarian class consciousness. Second, unlike earlier Marxists, especially Lenin, they rejected economic determinism. While highly influential, their work has been criticized by both orthodox Marxists and some Marxists involved in political practice for divorcing Marxist theory from practical struggle and turning Marxism into a purely academic enterprise.

Influential Marxists of the same period include the Third International's Georg Lukacs and Antonio Gramsci, who along with the Frankfurt School are often known by the term Western Marxism.

In 1949 Paul Sweezy and Leo Huberman founded Monthly Review, a journal and press, to provide an outlet for Marxist thought in the United States independent of the Communist Party.

In 1978, G. A. Cohen attempted to defend Marx's thought as a coherent and scientific theory of history by reconstructing it through the lens of analytic philosophy. This gave birth to Analytical Marxism, an academic movement which also included Jon Elster, Adam Przeworski and John Roemer. Bertell Ollman is another Anglophone champion of Marx within the academy.

The following countries had governments at some point in the twentieth century who at least nominally adhered to Marxism (those in bold still do as of 2006): Albania, Afghanistan, Angola, Bulgaria, Chile, China, Cuba, Czechoslovakia, East Germany, Ethiopia, Hungary, Laos, Mongolia, Mozambique, Nicaragua, North Korea, Poland, Romania, Russia, Yugoslavia, Vietnam. In addition, the Indian state of Kerala and West Bengal have had Marxist governments.

Marxist political parties and movements have significantly declined since the fall of the Soviet Union, with some exceptions, perhaps most notably Nepal.

Marx was ranked #27 on Michael H. Hart's list of the most influential figures in history.

In July 2005 Marx was the surprise winner of the 'Greatest Philosopher of All Time' poll by listeners of the BBC Radio 4 series In Our Time.

Criticisms

Many proponents of capitalism have argued that capitalism is a more effective means of generating and redistributing wealth than socialism or communism, or that the gulf between rich and poor that concerned Marx and Engels was a temporary phenomenon. Some suggest that self-interest and the need to acquire capital is an inherent component of human behavior, and is not caused by the adoption of capitalism or any other specific economic system (although economic anthropologists have questioned this assertion) and that different economic systems reflect different social responses to this fact. The Austrian School of economics has criticized Marx's use of the labor theory of value. In addition, the political repression and economic problems of several historical Communist states have done much to destroy Marx's reputation in the Western world, particularly following the fall of the Berlin Wall and the collapse of the Soviet Union, as the Soviet bureaucracy often invoked him in their propaganda. Although others argue that the former USSR was a variant of state capitalism whose collapse does not affect the veracity of Marxism, but vindicates it.

Marx has also been criticized from the Left. Some have argued that class is not the most fundamental inequality in history and call attention to patriarchy or race, as not being, as Marxists argue, dependent on class. Anarchists, on the other hand have always opposed Marxism, evne its most libertarian forms, as being too authoritarian, and missing the basic necessity of rebellion against authority by concentrating on economic matters.

Some today question the theoretical and historical validity of "class" as an analytic construct or as a political actor. In this line, some question Marx's reliance on 19th century notions that linked science with the idea of "progress" (see social evolution). Many observe that capitalism has changed much since Marx's time, and that class differences and relationships are much more complex — citing as one example the fact that much corporate stock in the United States is owned by workers through pension funds. Critics of this analysis retort that the top 1% of stock owners still own nearly 50% of the nation's publicly traded company stocks.

Still others criticize Marx from the perspective of philosophy of science. Karl Popper has criticized Marx's theories as he believed they were not falsifiable, which he argued would render some particular aspects of Marx’s historical and socio-political arguments unscientific, although Popper's falsifiability standard has itself always been controversial.

A common critique of Marx points out that the increasing class antagonisms he predicted never actually developed in the Western world following industrialization. While socioeconomic gaps between the bourgeoisie and proletariat remained, industrialization in countries such as the United States and Great Britain also saw the rise of a middle class not inclined to violent revolution, and of a welfare state that helped contain any revolutionary tendencies among the working class. While the economic devastation of the Great Depression broadened the appeal of Marxism in the developed world, future government safeguards and economic recovery led to a decline in its influence. In contrast, Marxism remained extremely influential in feudal and industrially underdeveloped societies such as Czarist Russia, where the Bolshevik Revolution was successful. This problem with classical Marxist theory was known from the beginning of the 20th century, and much of the work of Vladimir Lenin was dedicated to answering it. In essence, Lenin argued, taking the theory from several other contemporary Marxist writers, that through imperialism the bourgeoisie of wealthy countries is using "superprofits" from the imperial colonies to effectively bribe the working class back home in order to appease it.

Critics argue that the Soviet Union's numerous internal failings and subsequent collapse were a direct result of the practical failings of Marxism. Most Marxists on the contrary claim that it was precisely the abandonment of Marxism in the Soviet Union that led to its demise.

References

- Stephen Jay Gould, A Darwinian Gentleman at Marx's Funeral - E. Ray Lankester, Page 1, Find Articles.com (1999). (Marx's tomb)

- Daniel Little, The Scientific Marx, University of Minnesota Press (1986), trade paperback, 244 pages, ISBN 0816615055 (Marx's work considered as science)

- Duncan, Ronald, with Wilson, Colin, (editors) Marx Refuted, Bath, U.K.,(1987) ISBN 0906798-71-X

- David McLellen, Karl Marx: His Life and Thought

- Hal Draper, Karl Marx's Theory of Revolution (4 volumes). Monthly Review Press.

- Boris Nicolaevski & Otto Maenchen-Helfen, Karl Marx: Man and Fighter, Penguin books.

- Maximilien Rubel, Marx without myth: A chronological study of his life and work, Blackwell, 1975, ISBN 0631157808

- Francis Wheen, Karl Marx, Fourth Estate (1999), ISBN 1857026373 (biography of Marx)

- Isaiah Berlin, Karl Marx: His Life and Environment by Isaiah Berlin

Notes

- Francis Wheen, "Introduction", Karl Marx: A Life, New York: Norton, 2002.

See also

- Jenny von Westphalen

- Friedrich Engels

- Karl Marx House

- Marxism

- Class struggle

- historical materialism

- Das Kapital

- The Frankfurt School

- History of socialism

- Young Marx

- The 18th Brumaire of Louis Napoleon

External links

Bibliography and online texts

Error: No text given for quotation (or equals sign used in the actual argument to an unnamed parameter)

- Marx and Engels Internet Archive

- Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right (1843)

- On the Jewish Question (1843)

- Notes on James Mill (1844)

- Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts of 1844 (1844)

- Theses on Feuerbach (1845)

- The German Ideology (1845-46)

- The Poverty of Philosophy (1846-47)

- Wage-Labour and Capital (1847)

- Manifesto of the Communist Party (1847-48)

- The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte (1852)

- Grundrisse (1857-58)

- A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy (1859)

- Writings on the U.S. Civil War (1861)

- Theories of Surplus Value, 3 volumes (1862)

- Value, Price and Profit (1865)

- Capital vol. 1 (1867)

- The Civil War in France (1871)

- Critique of the Gotha Programme (1875)

- Notes on Wagner (1883)

- Capital, vol. 2 (1893)

- Capital, vol. 3 (1894)

- Letters (1833-95)

- Ethnological Notebooks — ISBN 9023209249 (1879-80)

- Works by Karl Marx at Project Gutenberg

- "The Reality Behind Commodity Fetishism" (in English) at Sic et Non (in German)

- Libertarian Communist Library Karl Marx Archive

- Karl Marx Biography

Biographies

- Friedrich Engels' Biography of Marx

- Vladimir Lenin's Karl Marx Biography

- Franz Mehring's Karl Marx: The Story of His Life

- Francis Wheen's Karl Marx: A Life

Articles and Entries

- Dead Sociologists - Karl Marx

- Ernest Mandel, Karl Marx (New Palgrave article)

- Marx on India and the Colonial Question from the Anti-Caste Information Page

- Portraits of Karl Marx

- The Karl Marx Museum

- Marxmyths.org - Various essays on misinterpretations of Marx

- Paul Dorn, The Paris Commune and Marx' Theory of Revolution

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy entry

- Why Marx is the Man of the Moment

- Heaven on Earth

- Jenny von Westphalen

- 1818 births

- People of the 1848 Revolutions

- 1883 deaths

- 19th century philosophers

- Atheist philosophers

- Atheists

- Economists

- Economic historians

- Fellows of the Royal Society of Arts

- German communists

- German philosophers

- Humanists

- Humanitarians

- Marxist theorists

- Marxists

- Materialists

- Philosophers

- Political economy

- Political philosophers

- Revolutionaries

- Social philosophers

- Sociologists

- Former students of the University of Bonn