This is an old revision of this page, as edited by ZéroBot (talk | contribs) at 00:57, 24 August 2012 (r2.7.1) (Robot: Adding ja:ホモ・ローデシエンシス). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 00:57, 24 August 2012 by ZéroBot (talk | contribs) (r2.7.1) (Robot: Adding ja:ホモ・ローデシエンシス)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)

| Homo rhodesiensis Temporal range: Pleistocene, 0.4–0.12 Ma PreꞒ Ꞓ O S D C P T J K Pg N ↓ | |

|---|---|

| |

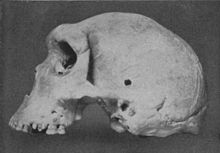

| Skull found in 1921 | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Primates |

| Family: | Hominidae |

| Tribe: | Hominini |

| Genus: | Homo |

| Species: | H. rhodesiensis |

| Binomial name | |

| †Homo rhodesiensis Woodward, 1921 | |

Homo rhodesiensis (Rhodesian man) is a hominin species described from the fossil Kabwe skull. Other morphologically-comparable remains have been found from the same, or earlier, time period in southern Africa (Hopefield or Saldanha), East Africa (Bodo, Ndutu, Eyasi, Ileret) and North Africa (Salé, Rabat, Dar-es-Soltane, Djbel Irhoud, Sidi Aberrahaman, Tighenif). These remains were dated between 300,000 and 125,000 years old.

Discovery

Kabwe skull or Kabwe cranium, or Broken Hill 1 is the type specimen. The cranium was found in a lead and zinc mine in Broken Hill, Northern Rhodesia (now Kabwe, Zambia) in 1921 by Tom Zwiglaar, a Swiss miner. In addition to the cranium, an upper jaw from another individual, a sacrum, a tibia, and two femur fragments were also found. The skull was dubbed Rhodesian Man at the time of the find, but is now commonly referred to as the Broken Hill Skull or the Kabwe Cranium.

The association between the bones is unclear, but the tibia and femur fossils are usually associated with the skull. Rhodesian Man is dated to be between 125,000 and 300,000 years old. Cranial capacity of the Broken Hill skull has been estimated at 1,100 cm³, which, when coupled with the more recent dating, makes any direct link to older skulls unlikely and negates the 1.75 to 2.5 million year earlier erroneous dating. Bada & al (1974) published direct date of 110 ka for this specimen measured by aspartic acid racemisation. The destruction of the paleoanthropological site has made layered dating impossible.

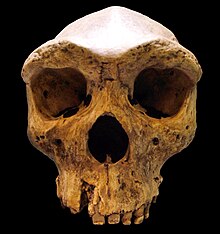

The skull is from an extremely robust individual, and has the comparatively largest brow-ridges of any known hominid remains. It was described as having a broad face similar to Homo neanderthalensis (i.e. large nose and thick protruding brow ridges), and has been interpreted as an "African Neanderthal". However, when regarding the skulls extreme robustness, recent research has pointed to several features intermediate between modern Homo sapiens and Neanderthal.

Most current experts believe Rhodesian Man to be within the group of Homo heidelbergensis though other designations such as Archaic Homo sapiens and Homo sapiens rhodesiensis have also been proposed. According to Tim White, it is probable that Rhodesian Man was the ancestor of Homo sapiens idaltu (Herto Man), which itself was the ancestor of Homo sapiens sapiens.

The skull has cavities in ten of the upper teeth and is considered the oldest occurrence of cavities for a hominid. Pitting indicates significant infection before death and implies a cause of death attributable to dental infection or chronic ear infection.

Another specimen "the hominid from Lake Ndutu" may approach 400,000 years old, and Clarke in 1976 classified it as Homo erectus. Undirect cranial capacity estimate is 1100 ml. Also supratoral sulcus morphology and presence of protuberance as suggested by Philip Rightmire : give the Nudutu occiput an appearance which is also unlike that of Homo Erectus but Stinger 1986 pointed that thickened iliac pillar is typical for Homo erectus.

Classification

In Africa, there is a distinct difference in the Acheulian tools made before and after 600,000 years ago with the older group being thicker and less symmetric and the younger being more extensively trimmed. This may be connected with the appearance (some 300,000 years later) of Homo rhodesiensis in the archaeological record at this time who may have contributed this more sophisticated approach.

Rupert Murrill has studied the relations between Archanthropus skull of Petralona (Chalcidice, Greece) and Rhodesian Man. Most current experts believe Rhodesian Man to be within the group of Homo heidelbergensis though other designations such as Homo sapiens arcaicus and Homo sapiens rhodesiensis have also been proposed. According to Tim White, it is probable that Homo rhodesiensis was the ancestor of Homo sapiens idaltu (Herto Man), which would be itself at the origin of Homo sapiens sapiens. No direct linkage of the species can so far be determined.

See also

- List of fossil sites (with link directory)

- List of hominina (hominid) fossils (with images)

References

- Rightmire, G. Philip. The Evolution of Homo Erectus: Comparative Anatomical Studies of an Extinct Human Species Cambridge University Press, 1993. ISBN 0-521-44998-7, ISBN 978-0-521-44998-4.

- Bada, Jeffrey L., Roy A. Schroeder, Reiner Protsch, and Rainer Berger. Concordance of Collagen-Based Radiocarbon and Aspartic-Acid Racemization Ages PNAS abstract URL.

- Amino Acid Racemization Dating of Fossil Bones

- "Kabwe 1". The Smithsonian Institution's Human Origin Program. Retrieved 2 November 2010.

- Rightmire, G. Philip (2005). "The Lake Ndutu cranium and early Homo Sapiens in Africa". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 61 (2): 245–254. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330610214. PMID 6410925.

- The Evolution of Homo Erectus: Comparative Anatomical Studies of an Extinct Human Species By G. Philip Rightmire Published by Cambridge University Press, 1993 ISBN 0-521-44998-7, ISBN 978-0-521-44998-4

Literature

| This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. Please help to improve this article by introducing more precise citations. (September 2008) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

- Woodward, Arthur Smith (1921). "A New Cave Man from Rhodesia, South Africa". Nature. 108 (2716): 371–372. doi:10.1038/108371a0.

- Singer Robert R. and J. Wymer (1968). "Archaeological Investigation at the Saldanha Skull Site in South Africa". The South African Archaeological Bulletin. 23 (3). The South African Archaeological Bulletin, Vol. 23, No. 91: 63–73. doi:10.2307/3888485. JSTOR 3888485.

- Murrill, Rupert I. (1975). "A comparison of the Rhodesian and Petralona upper jaws in relation to other Pleistocene hominids". Zeitschrift für Morphologie und Anthropologie. 66: 176–187..

- Murrill, Rupert Ivan (1981). Ed. Charles C. Thomas (ed.). Petralona Man. A Descriptive and Comparative Study, with New Information on Rhodesian Man. Springfield, Illinois: Thomas. ISBN 0-398-04550-X.

- Rightmire, G. Philip (2005). "The Lake Ndutu cranium and early Homo Sapiens in Africa". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 61 (2): 245–254. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330610214. PMID 6410925..

- Asfaw, Berhane (2005). "A new hominid parietal from Bodo, middle Awash Valley, Ethiopia". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 61 (3): 367–371. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330610311. PMID 6412559..

| Human evolution | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taxonomy (Hominins) |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ancestors |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Models |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Timelines | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Others | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||