This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Stephenb (talk | contribs) at 10:47, 11 October 2012 (Reverted 1 edit by 173.225.186.122 (talk) identified as vandalism to last revision by ClueBot NG. (TW)). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 10:47, 11 October 2012 by Stephenb (talk | contribs) (Reverted 1 edit by 173.225.186.122 (talk) identified as vandalism to last revision by ClueBot NG. (TW))(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)

| |||||

| Unit | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plural | Bitcoin, Bitcoins | ||||

| Symbol | |||||

| Nickname | BTC, Coins | ||||

| Denominations | |||||

| Subunit | |||||

| 0.00000001 | satoshi | ||||

| Plural | |||||

| satoshi | satoshis | ||||

| Coins | |||||

| Freq. used | 1-BTC | ||||

| Demographics | |||||

| Date of introduction | 3 January 2009Bitcoin Genesis Block | ||||

| User(s) | International | ||||

| Issuance | |||||

| Central bank | None. The Bitcoin Peer-to-peer Network regulates and distributes through consensus in protocol. | ||||

| Printer | Various | ||||

| Mint | Various | ||||

| Valuation | |||||

| Inflation | Limited release | ||||

| Source | Total BTC in Circulation | ||||

| Method | Geometric series every 4 years until 21 mil. BTC | ||||

Bitcoin (sign: ![]() , Ƀ, ฿; abbrv: BTC) is a peer-to-peer digital currency created by the pseudonymous entity, Satoshi Nakamoto.

One Bitcoin is divided into 100-million smaller units called satoshis.

, Ƀ, ฿; abbrv: BTC) is a peer-to-peer digital currency created by the pseudonymous entity, Satoshi Nakamoto.

One Bitcoin is divided into 100-million smaller units called satoshis.

Bitcoins can be sent, received and managed through various independent websites, PC clients and mobile device software. Physical banknote and coin forms can be traded as well. Internationally, Bitcoin can be donated, exchanged for goods and services or traded on exchanges for several other currencies such as the US dollar.

Administration

Bitcoin is administered through a decentralized peer-to-peer network. Nakamoto sidestepped the requirement of a central authority for Bitcoin by employing a proof-of-work approach in a peer-to-peer network to reach consensus in the Bitcoin network.

Bitcoins are issued according to rules agreed to by the majority of the computing power within the Bitcoin network. The core rules describing the predictable issuance of Bitcoins to its verifying servers, a voluntary and competitive transaction fee system and the hard limit of no more than 21 million Bitcoins issued in total.

Bitcoins do not have the backing of and do not represent any government-issued currency. The value of Bitcoins depends on the interpretation of the actions and software the Bitcoin network is based on. It does not require a central bank, state, or corporate-backer. In response, The Economist has described Bitcoin as "Monetarists Anonymous."

Payments

Bitcoin uses cryptographic technologies and a peer-to-peer network of computing power to enable users to make and verify irreversible, instant online Bitcoin payments, without an obligation to trust and use centralized banking institutions and authorities. Dispute resolution services are not made directly available. Instead it is left to the users to verify and trust the parties they are sending money to through their choice of methods.

Bitcoins are sent and received through clients and websites called wallets. They send and confirm transactions to the network through Bitcoin addresses, the identifiers for users' Bitcoin wallets within the network. Various wallets are available.

Bitcoin addresses

Bitcoin uses public-key cryptography using Elliptic Curve DSA. Every user in the Bitcoin network has a digital wallet containing a number of cryptographic keypairs. Payments are made to Bitcoin "addresses": human-readable strings of numbers and letters around 33 characters in length, always beginning with the digit 1 or 3, as in the example of 175tWpb8K1S7NmH4Zx6rewF9WQrcZv245W. These represent an ECDSA public key or combination thereof. The wallet's private keys are used to authorize transactions from that user's wallet.

Users obtain new Bitcoin addresses from any Bitcoin client software, including web-based Bitcoin wallets. Creating a new address is a completely offline process and requires no communication with the Bitcoin peer-to-peer network.

Most Bitcoin addresses look like meaningless random characters. It is possible to get more personalized addresses using programs that generate addresses rapidly, keeping ones matching some specific pattern. Examples such as 1LoveUNuf2az5e2m7v9kGRAFHYjDaf4jju with the 1LoveU prefix can be obtained in a few minutes on an average desktop computer.

Transaction fees

Transaction fees may be included with any transfer of Bitcoins. As of 2012 many transactions are processed in a way which makes no charge for the transaction. For transactions which draw coins from many Bitcoin addresses and therefore have a large data size, a small transaction fee is usually expected.

Confirmations

To prevent double-spending, the network implements what Nakamoto describes as a peer-to-peer distributed timestamp server, which assigns sequential identifiers to each transaction, which are then hardened against modification using the idea of chained proofs of work (shown in the Bitcoin client as confirmations). In his white paper, Nakamoto wrote: "we propose a solution to the double-spending problem using a peer-to-peer distributed timestamp server to generate computational proof of the chronological order of transactions."

Whenever a node broadcasts a transaction, the network immediately labels it as unconfirmed. The confirmation status reflects the likelihood that an attempt to reverse the transaction could succeed. Any transaction broadcast to other nodes does not become confirmed until the network acknowledges it in a collectively maintained timestamped-list of all known transactions, the blockchain.

History

| This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to itadding to it or making an edit request. (October 2012) |

In 2008, Satoshi Nakamoto self-published a paper outlining his work on The Cryptography Mailing list at metzdowd.com and then on 3 January 2009 released the open source project called Bitcoin and created the first block, called the "Genesis Block."

The Bitcoin network came into existence on 3 January 2009 with the release of the first open-source Bitcoin client, Bitcoind, and the issuance of the first Bitcoins. Prior to the invention of Bitcoin, electronic commerce could not securely operate without relying on a central authority to prevent double-spending.

In 2010, the initial exchange rates for Bitcoin were set by individuals on the bitcointalk forums. Today, the majority of Bitcoin exchanges occur on the Mt. Gox Bitcoin exchange.

In 2011, Wikileaks, Freenet, Singularity Institute, Internet Archive, Free Software Foundation and others, accept donations in Bitcoin. The Electronic Frontier Foundation did so for a while but has since stopped, citing concerns about a lack of legal precedent about new currency systems, and because they "generally don't endorse any type of product or service."

By mid-2011, some small businesses had started to adopt Bitcoin. LaCie, a public company, accepts Bitcoin for its Wuala service.

Economics

Initial distribution

Unlike fiat currency, Bitcoin has no centralized issuing authority. The network is programmed to increase the money supply as a geometric series until the total number of bitcoins reaches 21 million BTC. As of October 2012 slightly over 10 million of the total 21 million BTC had been created; the current total number created is available online. By 2013 half of the total supply will have been generated, and by 2017, three-quarters will have been generated. To ensure sufficient granularity of the money supply, clients can divide each BTC unit down to eight decimal places (a total of 2.1 × 10 or 2.1 quadrillion units).

The network as of 2012 required over one million times more work for confirming a block and receiving an award (50 BTC as of February 2012) than when the first blocks were confirmed. The network adjusts the difficulty every 2016 blocks based on the time taken to find the previous 2016 blocks such that one block is created roughly every 10 minutes. Thus the more computing power that is directed toward mining, the more computing power the network requires to complete a block confirmation and to receive the award. The network will also halve the award every 210,000 blocks, designed to occur about every four years.

Those who chose to put computational and electrical resources toward mining early on had a greater chance at receiving awards for block generations. This served to make available enough processing power to process blocks. Indeed, without miners there are no transactions and the Bitcoin economy comes to a halt.

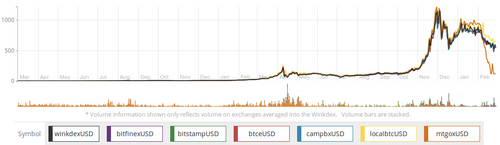

Exchange rate

| This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to itadding to it or making an edit request. (October 2012) |

Prices fluctuate relative to goods and services more than more widely accepted currencies; the price of a Bitcoin is not sticky.

In August 2012, 1 BTC traded at around $10.00 USD. Taking into account the total number of Bitcoins mined, the monetary base of the Bitcoin network stands at over 97 million USD.

Bitcoin as quasi-commodity money

Bitcoin shares characteristics of both commodity money and fiat money, but does not fit properly in either category. Bitcoin supersedes commodity money in value density, recognizability and divisibility It also resembles commodity money in that, at least during the expansion of the Bitcoin base, its value, assuming competing suppliers, is equal to its marginal cost of production. However, unlike commodity money, bitcoins, which exist only as numbers in a computer, have zero value as a commodity in the real world.On the other hand, fiat money commands a value higher than its costs of production, which raises the risk of mismanagement by their monopolistic suppliers.

For some of the reasons above, and due to commodities being "naturally" scarce while Bitcoin is only scarce in a contrived way and not subject to supply shocks in the usually understood sense, economist George Selgin classifies Bitcoin as quasi-commodity money.

Bitcoin mining

| This section may be too technical for most readers to understand. Please help improve it to make it understandable to non-experts, without removing the technical details. (October 2012) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Bitcoin mining nodes are responsible for managing the Bitcoin network. In turn, they receive the initial distribution of Bitcoins.

Bitcoins are awarded to Bitcoin nodes known as "miners" for the solution to a difficult proof-of-work problem which confirms transactions and prevents double-spending. This incentive, as the Nakamoto white paper describes it, encourages "nodes to support the network, and provides a way to initially distribute coins into circulation, since no central authority issues them."

Nakamoto compared the generation of new coins by expending CPU time and electricity to gold miners expending resources to add gold to circulation. Without a means of limiting production, however, blocks could be generated more and more easily as computing power increased or more clients tried to mine Bitcoins.

Mining and node operation

The mining and node software for the Bitcoin network is based on peer-to-peer networking, digital signatures and cryptographic proof to make and verify transactions. Nodes broadcast transactions to the network, which records them in a public record of all transactions, called the blockchain, after validating them with a proof-of-work system.

Satoshi Nakamoto designed the first Bitcoin node and mining software and developed the majority of the first implementation, Bitcoind, from 2007 to mid-2010.

Mining and node implementations include Bitcoind/Bitcoin-Qt, libbitcoin, cbitcoin and an open source implementation in Java called BitCoinJ. As of 2012, Bitcoind is the only one capable of fully verifying the Blockchain. It is still the most widely used implementation.

Every node in the Bitcoin network collects all the unacknowledged transactions it knows of in a file called a block, which also contains a reference to the previous valid block known to that node. It then appends a nonce value to this previous block and computes the SHA-256 cryptographic hash of the block and the appended nonce value. The node repeats this process until it adds a nonce that allows for the generation of a hash with a value lower than a specified target. Because computers cannot practically reverse the hash function, finding such a nonce is hard and requires on average a predictable amount of repetitious trial and error. This is where the proof-of-work concept comes in to play. When a node finds such a solution, it announces it to the rest of the network. Peers receiving the new solved block validate it by computing the hash and checking that it really starts with the given number of zero bits (i.e., that the hash is within the target). Then they accept it and add it to the chain.

The network's software confirms a transaction when it records it in a block. Further blocks generated further confirm it. After six confirmations, most Bitcoin clients consider a transaction confirmed beyond reasonable doubt. After this, it is overwhelmingly likely that the transactions are part of the main block chain rather than an orphaned one, and impractical to reverse.

Eventually, the block chain contains the cryptographic ownership history of all coins from their creator-address to their current owner-address. Therefore, if a user attempts to reuse coins he already spent, the network rejects the transaction.

The network must store the whole transaction history inside the block chain, which grows constantly as new records are added and never removed. Nakamoto conceived that as the database became larger, users would desire applications for Bitcoin that didn't store the entire database on their computer. To enable this, the system uses a Merkle tree to organize the transaction records in such a way that a future Bitcoin client can locally delete portions of its own database it knows it will never need, such as earlier transaction records of Bitcoins that have changed ownership multiple times, while keeping the cryptographic integrity of the remaining database intact. Some users will only need the portion of the block chain that pertains to the coins they own or might receive in the future. At the present time however, all users of the Bitcoin software receive the entire database over the peer-to-peer network after running the software the first time. As of August 2012, this database is just over 2 gigabytes (raw block data without any indexing or optimization).

Mining rewards

In addition to receiving the pending transactions confirmed in the block, a generating node adds a generate transaction, which awards new Bitcoins to the operator of the node that generated the block. The system sets the payout of this generated transaction according to its defined inflation schedule. The miner that generates a block also receives the fees that users have paid as an incentive to give particular transactions priority for faster confirmation.

The network never creates more than a 50 BTC reward per block and this amount will decrease over time towards zero, such that no more than 21 million will ever exist. As this payout decreases, the incentive for users to run block-generating nodes is intended to change to earning transaction fees.

Mining pools

Proof-of-work problems are especially suitable to GPUs and specialized hardware. Bitcoin users often pool computational effort to increase the stability of the collected fees and subsidy they receive.

Mining difficulty

In order to throttle the creation of blocks, the difficulty of generating new blocks is adjusted over time. If mining output increases or decreases, the difficulty increases or decreases accordingly.

The adjustment is done by changing the threshold that a hash is required to be less than. A lower threshold means fewer possible hashes can be accepted, and thus a higher degree of difficulty. The target rate of block generation is one block every 10 minutes, or 2016 blocks every two weeks. Bitcoin changes the difficulty of finding a valid block every 2016 blocks, using the difficulty that would have been most likely to cause the prior 2016 blocks to have taken two weeks to generate, according to the timestamps on the blocks. Technically, this is done by modeling the generation of Bitcoins as Poisson process. All nodes perform and enforce the same difficulty calculation.

Difficulty is intended as an automatic stabilizer allowing mining for Bitcoins to remain profitable in the long run for the most efficient miners, independently of the fluctuations in demand of Bitcoin in relation to other currencies.

Mining hardware

| This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to itadding to it or making an edit request. (October 2012) |

Bitcoins used to be mined through Intel/AMD CPUs. As of 2012, mining has gradually moved to GPU, FPGA and ASIC hardware. ASIC-based hardware for Bitcoin mining has been introduced by Butterfly Labs in June 2012.

Concerns

As an investment

Some criticize Bitcoin for being a Ponzi scheme in that it rewards early adopters through early Bitcoin mining and increasing exchange rates.

A frequent problem faced by retailers willing to accept Bitcoin is the high volatility of its exchange rate to conventional currencies, and the lack of futures contracts to hedge this volatility (although options—financial derivatives—are available). In a review of the virtual currency, James Surowiecki opined that hoarding by speculators represented one of the largest hindrances to accelerating its adoption. Gavin Andresen, the lead developer of Bitcoind, explicitly advised people "not to make heavy investments in Bitcoins", calling it "kind of like a high risk investment". Jered Kenna, CEO of TradeHill, formerly a major Bitcoin Exchange, also cautions potential investors, saying to the The New York Observer that Bitcoin was an experiment, "don't bet the house".

Privacy

Because transactions are broadcast to the entire network, they are inherently public. Unlike regular banking, which preserves customer privacy by keeping transaction records private, loose transactional privacy is accomplished in Bitcoin by using many unique addresses for every wallet, while at the same time publishing all transactions. As an example, if Alice sends 123.45 BTC to Bob, the network creates a public record that allows anyone to see that 123.45 has been sent from one address to another. However, unless Alice or Bob make their ownership of these addresses known, it is difficult for anyone else to connect the transaction with them. However, if someone connects an address to a user at any point they could follow back a series of transactions as each participant likely knows who paid them and may disclose that information on request or under duress.

It can be difficult to associate Bitcoin identities with real-life identities. This property makes Bitcoin transactions attractive to sellers of illegal products.

Jeff Garzik, one of the Bitcoin developers, explained as much in an interview and concluded that "attempting major illicit transactions with bitcoin, given existing statistical analysis techniques deployed in the field by law enforcement, is pretty damned dumb." He also said "We are working with the government to make sure indeed the long arm of the government can reach Bitcoin... the only way Bitcoins are gonna be successful is working with regulation and with the government."

Illicit use

Hacktivism

The hacking organization "LulzSec" accepted donations in Bitcoin, having said that the group "needs bitcoin donations to continue their hacking efforts".

Following the banking blockade instituted against Wikileaks by mainstream payment processors such as Visa, MasterCard and Paypal, the website accepts donations in Bitcoin.

Silk Road

Silk Road is an anonymous black market that uses only the Bitcoin.

In a 2011 letter to Attorney General Eric Holder and the Drug Enforcement Administration, senators Charles Schumer of New York and Joe Manchin of West Virginia called for an investigation into Silk Road and the Bitcoin. Schumer described the use of Bitcoins at Silk Road as a form of money laundering. Consequently, Amir Taaki of Intersango, a UK-based Bitcoin exchange, put out a statement clarifying that their Bitcoin exchanges follow proper regulations.

Botnet mining

In June 2011, Symantec warned about the possibility of botnets engaging in covert "mining" of Bitcoins (unauthorized use of computer resources to generate Bitcoins), consuming computing cycles, using extra electricity and possibly increasing the temperature of the computer. Later that month, the Australian Broadcasting Corporation caught an employee using the company's servers to generate Bitcoins without permission. Some malware also uses the parallel processing capabilities of the GPUs built into many modern-day video cards. In mid August 2011, Bitcoin miner botnets were found; trojans infecting Mac OS X have also been uncovered.

Theft and fraud

On 19 June 2011, a security breach of the Mt.Gox (an acronym for Magic: The Gathering Online Exchange, its original purpose) Bitcoin Exchange caused the price of a Bitcoin to briefly drop to US$0.01 on the Mt.Gox exchange (though it remained unaffected on other exchanges) after a hacker allegedly used credentials from a Mt.Gox auditor's compromised computer to illegally transfer a large number of Bitcoins to him- or herself and sell them all, creating a massive "ask" order at any price. Within minutes the price rebounded to over $15 before Mt.Gox shut down their exchange and canceled all trades that happened during the hacking period. The exchange rate of Bitcoins quickly returned to near pre-crash values. Accounts with the equivalent of more than USD 8,750,000 were affected.

In July 2011, The operator of Bitomat, the third largest Bitcoin exchange, announced that he lost access to his wallet.dat file with about 17,000 BitCoins (roughly equivalent to 220,000 USD at that time). He announced that he would sell the service for the missing amount, aiming to use funds from the sale to refund his customers.

In August 2011, MyBitcoin, one of popular Bitcoin transaction processors, declared that it was hacked, which resulted in it being shut down, with paying 49% on customer deposits, leaving more than 78,000 BitCoins (roughly equivalent to 800,000 USD at that time) unaccounted for.

In early August 2012, a lawsuit was filed in San Francisco court against Bitcoinica, claiming about 460,000 USD from the company. Bitcoinica was hacked twice in 2012, which led to allegations of neglecting the safety of customers' money and cheating them out of withdrawal requests.

In late August 2012, Bitcoin Savings and Trust was shut down by the owner, allegedly leaving around 5.6 million in debts; this led to allegations of the operation being a Ponzi scheme. In September 2012, it has been reported that U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission has started an investigation on the case.

In September 2012, Bitfloor Bitcoin exchange also reported being hacked, with 24,000 BitCoins (roughly equivalent to 250,000 USD) stolen. As a result, Bitfloor has suspended operations. The same month, Bitfloor has resumed operations, with its founder saying that he has reported the theft to FBI, and that he is planning to repay the victims, though time frame for such repayment is unclear.

See also

Digital money systems:

References

- eg "Bitbills".

- ^ Nakamoto, Satoshi. "Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System" (PDF). Cite error: The named reference "whitepaper" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Lowenthal, Thomas (8 June 2011). "Bitcoin: inside the encrypted, peer-to-peer digital currency". Ars Technica.

- "Cracking the Bitcoin: Digging Into a $131M USD Virtual Currency". Daily Tech. Retrieved 30 September 2012.

- "Bitcoin Wallet". Android Marketplace. Retrieved 29 September 2012.

- "Physical Bitcoins by Casascius". Casascius Coins. Retrieved 29 September 2012.

- "Bitbills". Bitbills. Retrieved 29 September 2012.

- "Mt. Gox Currency Exchange". Mt. Gox. Retrieved 29 September 2012.

- "Bitcoin: The Cryptoanarchists' Answer to Cash". IEEE.org. June 2012. Retrieved 2012-06-05.

- http://www.economist.com/node/21563752?fb_action_ids=10152174673925385&fb_action_types=og.likes&fb_ref=scn%2Ffb_ec%2Fmonetarists_anonymous&fb_source=aggregation&fb_aggregation_id=246965925417366

- "The Bitcoin Network". Bitcoin Wiki. Retrieved 6 September 2012.

- "Bitcoin P2P e-cash paper".

- Satoshi's posts to Cryptography mailing list

- "Block 0 – Bitcoin Block Explorer". The Genesis Block.

- "Block 0 – Bitcoin Block Explorer".

- "Bitcoin v0.1 released".

- "SourceForge.net: Bitcoin".

- "Factbox – What is Bitcoin – currency or con?".

... A problem facing creators of non-physical currencies is how to ensure users do not spend their money twice. Before Bitcoin was invented...

- "Mt.Gox data". Bitcoincharts.

- Greenberg, Andy (2011-06-14). "WikiLeaks Asks For Anonymous Bitcoin Donations – Andy Greenberg – The Firewall – Forbes". Blogs.forbes.com. Retrieved 2011-06-22.

- "/donate". The Freenet Project. Retrieved 2011-06-22.

- SIAI donation page

- Internet Archive donation page

- Other ways to donate

- "EFF and Bitcoin | Electronic Frontier Foundation". Eff.org. 2011-06-14. Retrieved 2011-06-22.

- "Trade – Bitcoin". En.bitcoin.it. Retrieved 2012-01-24.

- "Secure Online Storage – Backup. Sync. Share. Access Everywhere". Wuala. Retrieved 2012-01-24.

- Sponsored by. "Virtual currency: Bits and bob". The Economist. Retrieved 2011-06-22.

- Geere, Duncan. "Peer-to-peer currency Bitcoin sidesteps financial institutions (Wired UK)". Wired.co.uk. Retrieved 2011-06-22.

- "Total Number of Bitcoins in Existence". Bitcoin Block Explorer. Retrieved 2012-10-03.

- ^ Nathan Willis (2010-11-10). "Bitcoin: Virtual money created by CPU cycles". LWN.net.

- "Bitcoin History Stats". Retrieved 12 December 2011.

- http://www.bitcoinwatch.com/ Bitcoin statistics

- ^ Selgin, George. "Quasi-Commodity Money. Abstract". Retrieved 8 April 2012. Cite error: The named reference "selgin" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- Davis, Joshua (10 November 2011). "The Crypto-Currency". Wired Magazine. Retrieved 11 November 2011.

- "Questions about Bitcoin". Bitcoin forum. 2009-12-10.

- "cbitcoin". Retrieved 3 October 2012.

- angry tapir, timothy (23 March 2011). "Google Engineer Releases Open Source Bitcoin Client". Slashdot. Retrieved 2011-05-18.

- Dirk Merkel (10 January 2012). "Bitcoin for beginners: The BitcoinJ API". JavaWorld. Retrieved 2012-08-03.

- https://en.bitcoin.it/Difficulty

- ^ "Bitpay Breaks Daily Volume Record with Butterfly ASIC mining release". Bitcoin Magazine.

- "Bitcoins, a Crypto-Geek Ponzi Scheme". Retrieved 15 June 2011.

- James Surowiecki (September/October 2011). "Cryptocurrency". Technology Review: 106.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - "/59/Bitcoin – a Digital, Decentralized Currency (at 31 min.)". omega tau podcast. 19 March 2011.

- Jeffries, Adrianne (2011-05-29). "Bit O'Money: Who's Behind the Bitcoin Bubble? | The New York Observer". Observer.com. Retrieved 2012-01-24.

- "Bitcoin: The Cryptoanarchists' Answer to Cash". IEEE.org. June 2012. Retrieved 2012-06-05.

- ^ Fergal Reid and Martin Harrigan (24 July 2011). An Analysis of Anonymity in the Bitcoin System. An Analysis of Anonymity in the Bitcoin System.

- "Bitcoin not so anonymous, Irish researcher says – Cyrus Farivar – Science and Technology". Deutsche Welle. 2011-06-01. Retrieved 2011-07-29.

- Andy Greenberg (20 April 2011). Crypto Currency. Forbes Magazine.

- Madrigal, Alexis (2011-06-01). "Libertarian Dream? A Site Where You Buy Drugs With Digital Dollars". The Atlantic Monthly. Retrieved 2011-06-05.

- ^ Chen, Adrian (1 June 2011). "The Underground Website Where You Can Buy Any Drug Imaginable". Gawker.

- "Libertarian Dream? A Site Where You Buy Drugs With Digital Dollars – Alexis Madrigal – Technology". The Atlantic. 2011-06-01. Retrieved 2011-06-22.

- "CBSNewsOnline: BitCoin: The Future of Currency".

- Reisinger, Don (2011-06-09). "Senators target Bitcoin currency, citing drug sales | The Digital Home – CNET News". News.cnet.com. Retrieved 2011-06-22.

- Olson, Parmy (6 June 2011). "LulzSec Hackers Post Sony Dev. Source Code, Get $7K Donation – Parmy Olson – Disruptors – Forbes". Blogs.forbes.com. Retrieved 2011-06-22.

- http://shop.wikileaks.org/donate#dbitcoin

- ^ Staff (12 June 2011). "Silk Road: Not Your Father's Amazon.com". NPR.

- Updated: 17 June 2011 (2011-06-17). "Bitcoin Botnet Mining | Symantec Connect Community". Symantec.com. Retrieved 2012-01-24.

{{cite web}}: Text "Translations available: 日本語" ignored (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - "Researchers find malware rigged with Bitcoin miner". ZDNet. 2011-06-29. Retrieved 2012-01-24.

- "ABC employee caught mining for Bitcoins on company servers". The Next Web. 2011-06-23. Retrieved 2012-01-24.

- Goodin, Dan (16 August 2011). "Malware mints virtual currency using victim's GPU".

- "Infosecurity – Researcher discovers distributed bitcoin cracking trojan malware". Infosecurity-magazine.com. 2011-08-19. Retrieved 2012-01-24.

- "Mac OS X Trojan steals processing power to produce Bitcoins – sophos, security, malware, Intego – Vulnerabilities – Security". Techworld. 2011-11-01. Retrieved 2012-01-24.

- Clarification of Mt Gox Compromised Accounts and Major Bitcoin Sell-Off

- YouTube. Bitcoin Report

- ^ Jason Mick, 19 June 2011, Inside the Mega-Hack of Bitcoin: the Full Story, DailyTech

- Timothy B. Lee, 19 June 2011, Bitcoin prices plummet on hacked exchange, Ars Technica

- Mark Karpeles, 20 June 2011, Huge Bitcoin sell off due to a compromised account – rollback, Mt.Gox Support

- Chirgwin, Richard (2011-06-19). "Bitcoin collapses on malicious trade – Mt Gox scrambling to raise the Titanic". The Register.

- Third Largest Bitcoin Exchange Bitomat Lost Their Wallet, Over 17,000 Bitcoins Missing. SiliconAngle

- MyBitcoin Spokesman Finally Comes Forward: “What Did You Think We Did After the Hack? We Got Shitfaced”. BetaBeat

- Search for Owners of MyBitcoin Loses Steam. BetaBeat

- Bitcoinica users sue for $460k in lost Bitcoins. Arstechnica

- First Bitcoin Lawsuit Filed In San Francisco. IEEE Spectrum

- "Bitcoin ponzi scheme – investors lose $5 million USD in online hedge fund". RT.

- Jeffries, Adrianne. "Suspected multi-million dollar Bitcoin pyramid scheme shuts down, investors revolt". The Verge.

- Mick, Jason. ""Pirateat40" Makes Off $5.6M USD in BitCoins From Pyramid Scheme". DailyTech.

- Bitcoin: How a Virtual Currency Became Real with a $5.6M Fraud. PandoDaily

- Bitcoin 'Pirate' scandal: SEC steps in amid allegations that the whole thing was a Ponzi scheme . The Telegraph

- Bitcoin theft causes Bitfloor exchange to go offline. BBC

- Bitcoin exchange BitFloor suspends operations after $250,000 theft Bitcoin exchange BitFloor suspends operations after $250,000 theft. The Verge

- Bitcoin exchange back online after hack. PCWorld

External links

- Bitcoind/Bitcoin-Qt website

- The Bitcoin wiki

- Charts and Stats for the Bitcoin network

- Bitcoin Block Explorer