This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Tomcat7 (talk | contribs) at 12:40, 26 December 2012 (→Early writing). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 12:40, 26 December 2012 by Tomcat7 (talk | contribs) (→Early writing)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)

| Fyodor Dostoyevsky | |

|---|---|

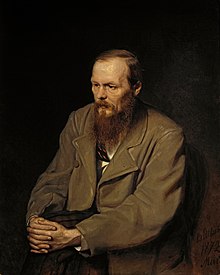

Portrait of Dostoyevsky in 1872 painted by Vasily Perov Portrait of Dostoyevsky in 1872 painted by Vasily Perov | |

| Born | Fyodor Mikhaylovich Dostoyevsky (1821-11-11)11 November 1821 Moscow, Russian Empire |

| Died | 9 February 1881(1881-02-09) (aged 59) Saint Petersburg, Russian Empire |

| Nationality | Russian |

| Education | Military engineering-technical university, St. Petersburg |

| Period | 1846–1881 |

| Genre | Novel, short story, journalism |

| Subject | Psychology, philosophy, religion |

| Literary movement | Realism |

| Notable works | |

| Spouse |

|

| Children | Sonya (1868) Lyubov (1869–1926) Fyodor (1871–1922) Alexey (1875–1878) |

| Signature | |

Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoyevsky (Russian: Фёдор Миха́йлович Достое́вский, IPA: [ˈfʲodər mʲɪˈxajləvʲɪtɕ dəstɐˈjefskʲɪj] ; 11 November 1821 – 9 February 1881), sometimes transliterated Dostoevsky, was a Russian novelist, short story writer, and essayist. Dostoyevsky's literary works explore human psychology in the troubled political, social and spiritual context of 19th-century Russia. Although Dostoyevsky began writing in the mid-1840s, his most memorable works – including Crime and Punishment, The Idiot and The Brothers Karamazov – are from his later years. Altogether he wrote eleven novels, three novellas, seventeen short novels, and three essays, and has been judged by many literary critics to be one of the greatest and most prominent psychologists in world literature.

Dostoyevsky was born in the Mariinsky hospital in Moscow, Russia. He was introduced to literature at an early age – through fairy tales and legends, but also through books by English, French, German and Russian authors. His mother's sudden death in 1837, when he was in his early teens, devastated him. Around that time, he left school to enter the Nikolayev Military Engineering Institute. After graduating, he worked as an engineer and briefly enjoyed a liberal lifestyle. He soon began translating books to earn extra money. In the mid-1840s he wrote his first novel, Poor Folk, which allowed him to join St Petersburg's literary circles. In 1849 he was arrested for his involvement with the Petrashevsky Circle – a secret society of liberal utopians as well as a literary discussion group. He and other members were condemned to death, but the penalty proved to be a mock execution and the sentence was commuted to four years' hard labour in Siberia. After his release, Dostoyevsky was forced to serve as a soldier, but was discharged from the military due to his ill health.

In the following years Dostoyevsky worked as a journalist, publishing and editing several magazines of his own and later a serial, A Writer's Diary. He began travelling around western Europe, and developed a gambling addiction which led to financial hardship and an embarrassing period of begging for money. Adding to his woes, he suffered from epilepsy throughout his adult life. But through his indefatigable energy and the sheer volume of his work, he eventually became one of the most widely read and renowned Russian writers. His books have been translated into more than 170 languages and have sold around 15 million copies. Dostoyevsky has influenced a multitude of writers of varying genres, from Anton Chekhov and James Joyce to Ernest Hemingway, Jean-Paul Sartre and Ayn Rand, among others.

Early life

Family background

Fyodor Dostoyevsky was born on 30 October 1821 (11 November 1821, according to the Gregorian Calendar), the second child of Mikhail Dostoyevsky and Maria Nechayeva. The Dostoyevskys were a multi-ethnic and multi-denominational Lithuanian noble family from the Pinsk region with roots dating to the 16th century. Branches of the family included Orthodox and Catholic members, but Dostoyevsky's immediate ancestors were of the non-monastic clergy class. On his mother's side, Dostoyevsky was descended from Russian merchants.

Dostoyevsky's paternal great-grandfather and grandfather were priests in the Ukrainian town of Bratslava. Mikhail was expected to join the clergy, like his father, but instead of going into seminary, he ran away from home and broke with his family permanently. In 1809, when he was twenty years old, Mikhail was admitted to Moscow's Imperial Medical-Surgical Academy. From there, he was assigned to a Moscow hospital where he served as military doctor and in 1818 was appointed to senior physician. In 1819, he married Maria Isayevna. The following year, he resigned from his post to accept a new job at the Mariinsky Hospital for the poor. After the birth of his first two sons, Mikhail and Fyodor, he was promoted to collegiate assessor, a position that raised his legal status to nobility and enabled him to acquire a small estate in Darovoye, a town 150 versts (about 150 km or 100 miles) away from Moscow. Dostoyevsky's parents subsequently had five more children.

Childhood

Dostoyevsky was raised in the family home on the grounds of the Mariinsky Hospital. The family usually spent the summers in their estate in Darovoye when he was a child. At the age of three, Fyodor was introduced to heroic sagas, fairy tales and legends and – influenced by his nannies – developed a deeply ingrained religious piety. His nanny, Alina Frolovna, and a family friend, the serf and farmer Marei from Darovoye, were influential figures in his childhood; Marei helped him deal with his hallucinations, possibly caused by his reading of Gothic literature, a genre that enthralled him. After discovering the hospital garden, which was separated by a large fence from the house private garden, Dostoyevsky would often talk with the patients, even though his parents forbade it. He once encountered a nine-year-old girl who had been raped, an event that traumatised him. Since Dostoyevsky's parents valued education, his mother taught him to read and write, using the Bible, when he was four. He always looked forward to his parents' nightly readings. They introduced him to Russian and world literature at an early age, including national writers Karamzin, Pushkin and Derzhavin; gothic literature, such as Ann Radcliffe; Romantic works of Friedrich Schiller and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe; heroic tales by Cervantes and Walter Scott; and Homer's epics.

In 1833, Dostoyevsky's father sent him to a boarding school which taught in French, and, one year later, to the best private boarding school in Moscow, the "College for Noble Male Children". To pay off his school fees, his father had to take out loans and extend his private medical practice. Dostoyevsky felt out of place amongst his aristocratic classmates at the Moscow school, an experience later reflected in some of his works, notably The Adolescent. A school day, which usually began at six o'clock in the morning and ended nine at night, offered a diverse number of subjects, including Greek, German, English, French, Bible, history, logic, rhetoric, arithmetic, geometry, history, physics, fiction, drawing and dance.

Youth

On 27 September 1837 Dostoyevsky's mother died of tuberculosis. He contracted a serious throat disease soon after, giving him a brittle voice throughout his life. The previous May his parents had sent Fyodor and his brother Mikhail to St Petersburg to attend the Nikolayev Military Engineering Institute, forcing the brothers to abandon their academic studies at the Moscow college for a military career. On the way to St Petersburg, Dostoyevsky witnessed a violent incident in a post house: a member of the military police beat a carter, who subsequently took out his anger on his horse, whipping it. He referred to this incident in his serial A Writer's Diary. Dostoyevsky entered the academy in 1838, but only with the help of family members, who – unknown to him – had paid the tuition fees. Mikhail was refused admission on account of his poor health, which was the reason why Mikhail was sent to the Academy in Reval, Estonia; he was separated from his brother.

Dostoyevsky did not enjoy the academy, primarily because of his lack of interest in science, mathematics and military engineering and his preference for drawing and architecture. As his friend Konstantin Trutovsky once said, "There was no student in the entire institution with less of a military bearing than F. M. Dostoyevsky. He moved clumsily and jerkily; his uniform hung awkwardly on him; and his knapsack, shako and rifle all looked like some sort of fetter he had been forced to wear for a time and which lay heavily on him." Among his 120 classmates, who were mainly of Polish or Baltic-German descent, Dostoyevsky's character and interests made him an outsider: in contrast with many of his class fellows, he was brave and had a strong sense of justice, protected newcomers, aligned himself with teachers, criticised corruption among officers and helped poor farmers. Although he was a loner and lived in his own literary world, his classmates respected him. His reclusive way of life and his interest in religion earned him the nickname "Monk Photius".

Dostoyevsky's first seizure may have occurred after learning of the death of his father on 16 June 1839, although reports of this originated from accounts (now considered unreliable) written by his daughter, which were later expanded by Sigmund Freud. The father's official cause of death was an apoplectic stroke, although a neighbour accused the father's serfs of murder. Had the serfs been found guilty and sent to Siberia, the neighbour, Pavel Khotiaintsev, would have been in a position to buy the vacated land. The serfs were found innocent in a criminal trial in Tula, but Dostoyevski's brother Andrei perpetuated the story. After his father's death, Dostoyevsky continued with his studies, passed his exams and obtained the rank of engineer cadet, which gave him the right to live away from the academy. After a short visit to his brother Mikhail in Reval, Fyodor frequently went to concerts, operas, plays and ballets. It was during this time that two of his friends initiated him into gambling.

In August 1843 he took a job as a military draftsman (a job he found "as boring as potatoes"), and lived with Adolph Totleben in an apartment owned by the German-Baltic Dr A. Riesenkampf, a friend of his brother Mikhail. As he had done when he was a child, Dostoyevsky continued to show concern for the poor and the sick. He earned some badly-needed money by translating works of literature into Russian, He graduated from the academy on 19 October 1844 as a lieutenant. Already in financial trouble, Dostoyevsky decided to write his own novel.

Career

Early career

In 1844, Dostoyevsky shared an apartment with Dmitry Grigorovich, a friend from the academy, and began on his first novel, hoping to obtain a large readership to improve his finances. In a letter to his brother Mikhail he wrote, "It's simply a case of my novel covering all. If I fail in this, I'll hang myself." In May 1845 he finished the manuscript, Poor Folk, and asked Grigorovich to read the novel aloud. Grigorovich was so impressed that the same night he took it to his friend the poet Nikolay Nekrasov, who also became enthusiastic about it and called Dostoyevsky the "New Gogol". The next day, Nekrasov showed the manuscript to Vissarion Belinsky, the most renowned and influential literary critic of the time. Skeptical at first, Belinsky was astonished after reading it, so much so that he described it as Russia's first "social novel". Poor Folk was released on 15 January 1846 in the almanac St Petersburg Collection and was an enormous commercial success.

Shortly after the publication of Poor Folk, Dostoyevsky wrote his second novel, The Double. The book was published in February 1846, although it had already appeared in the journal Annals of the Fatherland on 30 January. In the 1840s, socialism began to be more influential in Russia, to the detriment of romanticism and idealism. Dostoyevsky, who discovered socialism around 1846, was initially influenced by the French socialists Fourier, Cabet, Proudhon and Saint Simon. Through his relationship with Belinsky, Dostoyevsky expanded his knowledge of the philosophy of socialism and was attracted to its logic, its sense of justice and its preoccupation with the destitute and disadvantaged. His relationship with Belinsky, however, became increasingly strained as Belinsky's atheism and dislike of religion clashed with Dostoyevsky's Orthodox beliefs, so he parted company with him and his associates. In his later books, Dostoyevsky focused on the issues of the existence of God and nihilism, as well as the nature of human coexistence, the requirements of fraternity and the coherence between freedom and fortune.

After his second novel received negative reviews, Dostoyesvsky's health declined and he suffered more epileptic seizures, but he continued his prolific writing. From 1846 to 1848 he released a number of short stories in the magazine Annals of the Fatherland, including "Mr. Prokharchin", "The Landlady", "A Weak Heart" and "White Nights". Since these stories were unsuccessful, Dostoyevsky found himself in financial trouble yet again and so decided to join the utopian socialist Betekov circle, a tight-knit community that helped him to survive. When the circle dissolved, Dostoyevsky befriended Apollon Maykov and his brother Valerian; after Valerian's death, Apollon became an important figure in Dostoyevsky's life. In 1846, on recommendation of the poet Aleksey Pleshcheyev, he joined the socio-Christian Petrashevsky Circle, founded by Mikhail Petrashevsky, who had proposed social reforms in Russia. "The first Russian Communist" Mikhail Bakunin once wrote to Alexander Herzen, that the group was "the most innocent and harmless company" and its members "systematic opponents of all revolutionary goals and means". Dostoyevsky used the circle's library on Saturdays and Sundays, and sometimes participated in their discussions of themes like freedom from censorship and the abolition of serfdom.

In 1849 the first parts of Netochka Nezvanova, a novel Dostoyevsky had been planning since 1846, were published in Annals of the Fatherland, but his banishment brought it to an end. Dostoyevsky never tried to complete it and the novel remained unfinished.

Exile in Siberia

Dostoyevsky and other members of the Petrashevsky Circle were denounced to Liprandi, an official for the Ministry of International Affairs. Dostoyevsky was accused of reading several works by Belinsky, including Correspondence with Gogol, Criminal Letters and The Soldier's Speech, and of passing copies of these and other works. Antonelli, the government agent who had reported the group, wrote in his statement: " summoned a considerable amount of enthusiastic approval from the society, in particular on the part of Belasoglo and Yastrzhembsky, especially at the point where Belinsky says that religion has no basis among the Russian people. It was proposed that this letter be distributed in several copies." Dostoyevsky responded to these charges by declaring that he had read the essays only "as a literary monument, neither more nor less" and argued about "personality and human egoism" instead of politics. But even so, he and his companions – deemed to be "conspirators" – were arrested on 22 April 1849 on the request of Count A. Orlov and Emperor Nicolas I, who feared a revolution like the Decembrist revolt of 1825 in Russia and the Revolutions of 1848 in Europe. The members were brought to the well-defended Peter and Paul Fortress, where the most dangerous convicts were sent.

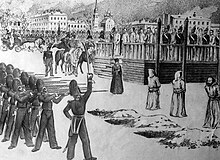

The future of the convicts was discussed for four months by an investigative commission headed by the Tsar. It was deliberated over by commander General Ivan Nabokov, senator Count Pavel Gagarin, Count Vasili Dolgorukov, Generals Yakov Rostovtsev and head of the secret police Leonty Dubelt. They decided to execute the convicts. On 23 December 1849, the members of the circle were brought to Semyonov Place in St Petersburg. In the last minute, the execution was stayed when a cart came running. The Tsar had wrote a letter to general adjutant Sumarokov in which the people were pardoned. Dostoyevsky's sentence was commuted to four years of exile with hard labour at a katorga prison camp in Omsk, Siberia, followed by a term of compulsory military service. After a fourteen-day sleigh ride, they reached Tobolsk in Siberia, a staying place for Russian prisoners. Despite all the burden, Dostoyevsky netherless stayed calm and knew how to take heart from such situations. He consoled and uplifted other prisoners, such as Ivan Yastrzhembsky, one of the members of the Petrashevsky Circle, who was surprised about his kindness and eventually decided not to commit suicide. In Tobolsk the members received food and clothes by the Decembrist women, and additionally a New Testament booklet with a ten-ruble banknote inside each. Eleven days later, Durov and Dostoyevsky reached Omsk, whose barracks he described as follows:

In summer, intolerable closeness; in winter, unendurable cold. All the floors were rotten. Filth on the floors an inch thick; one could slip and fall ... We were packed like herrings in a barrel ... There was no room to turn around. From dusk to dawn it was impossible not to behave like pigs ... Fleas, lice, and black beetles by the bushel ...

— Fyodor Dostoyevsky, Pisma, I: pp. 135–7.

Classified as "one of the most dangerous convicts", Dostoyevsky had his feet and hands permanently chained until his release. He unsuccessfully appealed for the release from the chains. During his imprisonment, he was not allowed to read anything except his New Testament; he would randomly open its pages whenever in doubt. In addition to his epileptic seizures, Dostoyevsky had haemorrhoids and was "burned by some fever, trembling and feeling too hot or too cold every night" and "losing weight". The smell of a privy was distributed throughout the building, and the bathroom was a small room occupying more than 200 people. Sometimes he was sent to the military hospital, where he had the opportunity to read Dickens novels and newspapers. Dostoyevsky was generally respected by the prisoners, but despised by some because of xenophobic statements.

Release from prison

After his release on 14 February 1854, Dostoyevsky asked his brother Mikhail to help him financially and to send him books by authors such as Vico, Guizot, Ranke, Hegel and Kant. He also began to write The House of the Dead, basing it on his experience in prison. It became the first novel about Russian prisons. Before moving to Semipalatinsk in mid-March, where he was forced to serve in the Siberian Army Corps of the Seventh Line Battalion, Dostoyevsky had overnighted with the Ivanovs and met geographer Pyotr Semyonov and ethnographer Shokan Walikhanuli. The steppe-like region with the many mosques conveyed him an unknown picture of the life outside of European Russia. Around November 1854, he met Baron Alexander Egorovich Wrangel, an admirer of his books who had attended the mock execution. They both rented houses outside Semipalatinsk, in the "Cossack Garden".

In Semipalatinsk, Dostoyevsky began to work as tutor to several schoolchildren and so came into social contact with several upper-class families. This is how he made the acquaintance of Lieutenant-Colonel Belikhov, who used to invite him to read out passages from newspapers and magazines. During a visit to Belikhov, Dostoyevsky met the family of Alexander Ivanovich Isaev and Maria Dmitrievna Isaeva, and soon fell in love with her. Alexander Isaev took a new post in Kuznetsk, where he died in August 1855. Maria then moved with Dostoyevsky to Barnaul. Dostoyevsky sent a letter through Wrangel to General Eduard Totleben, apologising for his activity in several Utopian circles and, as a result, in 1856 he obtained the right to publish books and to marry, but remained under police surveillance for the rest of his life. He married Maria in Semipalatinsk on 7 February 1857.

In 1859 Dostoyevsky was released from military service as his health had worsened since his marriage. He was also granted permission to return to Russia, first to Tver – where he met his brother for the first time in ten years – then to St Petersburg. He arrived there on 16 September 1859 and subsequently joined the Society for Aid of Needy Writers and the Literary Fund. Its goal was to help scholars and writers who were in trouble, such as those arrested on political grounds.

"A Little Hero" (Dostoyevsky's only work completed while in prison) appeared in a journal, while "Uncle's Dream" and "The Village of Stepanchikovo" were not published until 1860. Notes from the House of the Dead was released in Russky Mir ("Russian World") in September 1860; "The Insulted and the Injured", in the new Vremya magazine, which had been created with the help of funds from his brother's cigarette factory.

Dostoyevsky travelled to western Europe for the first time on 7 June 1862. He went to the German cities of Cologne, Berlin, Dresden and Wiesbaden and to Belgium and Paris afterwards. In London he met Herzen and visited the Crystal Palace. He then traveled with Strakhov through Switzerland and several cities in northern Italy, Turin, Livorno and Florence among them. He wrote mainly negative comments about these countries in Winter Notes on Summer Impressions, where he criticised capitalism, social modernisation, materialism, Catholicism and Protestantism.

From August to October 1863 Dostoyevsky made another trip to western Europe. In Paris he met his second love, Polina Suslova. Once again, he lost all his money gambling in Wiesbaden and Baden-Baden. He then wrote a letter to Wrangel, asking for a 100-thaler loan and mentioning his next novel for the first time. In 1864, after the successive deaths of his wife Maria and his brother, Dostoyevsky became the lone parent of his stepson Pasha and, almost immediately afterwards, of Mikhail's family. The failure of Epokha, the magazine he had founded with his brother after the suppression of Vremya, worsened his financial situation. The continued help of his relatives and friends, however, prevented him from going bankrupt.

Travels

The first two parts of Dostoyevsky's sixth novel, Crime and Punishment, were published in January and February 1866 in the periodical The Russian Messenger, bringing the magazine at least 500 new subscribers. The complete novel was also a success. The critic Strakhov, generally satisfied with the novel, remarked that "Only Crime and Punishment was read in 1866" and said that Dostoyevsky had managed to portray, aptly and realistically, a Russian person. Initially, however, the novel received a mixed reception from critics, with most of the negative responses coming from nihilists. Grigory Eliseev of the radical magazine The Contemporary called the novel a "fantasy according to which the entire student body is accused without exception of attempting murder and robbery". Dostoyevsky returned to St Petersburg in mid-September and promised his editor, Fyodor Stellovsky, that he would complete the novel The Gambler by November, although he had not yet written a single line. Milyukov, one of Dostoyevsky's friends, advised him to hire a secretary. Dostoyevsky contacted Pavel Olkhin, one of the best stenographers in St Petersburg, who recommended his pupil Anna Grigoryevna Snitkina. He hired Snitkina in October 1866, she registered his dictation in shorthand and The Gambler, a short novel focused on gambling, was completed within 26 days on 30 October.

On 15 February 1867, Dostoyevsky married Anna Snitkina in the Trinity Cathedral in St Petersburg. The 7,000 rubles he had earned from Crime and Punishment did not cover all their debts so, to avoid a compulsory auction, Anna sold furniture, jewellery and her piano. On 14 April 1867, they began a delayed honeymoon in Germany with the money raised. They stayed in Berlin, and later visited the Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, where he sought inspiration for his writing. Three weeks later Dostoyevsky travelled to Homburg, where he lost all of his wife's money gambling. They continued their trip through Germany, visiting Frankfurt, Darmstadt, Heidelberg and Karlsruhe. In Baden-Baden, Anna became pregnant. In Geneva they were low on funds and had to pawn more of their possessions, but found lodging and good doctors. Their first child, Sonya was born on 5 March 1868. Three months later the baby died from pneumonia. Again in financial trouble due to his addiction, he returned to Geneva. In September 1868, Dostoyevsky started to work on The Idiot, managing to complete 100 pages in just 23 days. Dostoyevsky felt uncomfortable with the surroundings. Thus they left Geneva and moved to Vevey and then to Milan so that he could complete his novel. After enduring some rainy autumn months in Milan, they travelled to Florence. The Idiot was completed there in January 1869 and serialised in The Russian Messenger.

In Dresden, Anna gave birth to Lyubov on 26 September 1869. In April 1871 Dostoyevsky made a final visit to a gambling hall in Wiesbaden. According to Anna, Dostoyevsky was cured of his addiction after the birth of their second daughter, but whether or not this is true is open to speculation. Another reason for his abstinence might have been the closure of casinos in Germany in 1872 and 1873. It was not until the rise of Adolf Hitler that these were reopened. Anna's younger brother, Ivan Snitkin, also visited the couple in autumn 1869. A pupil at the Petrovsky Agricultural Academy in Moscow, Snitkin told them about the unrest among the students there and mentioned a classmate of his, Ivan Ivanov, who was involved in the Nihilist movement, led by Sergey Nechayev. Nechayev, influenced by Bakunin's Alliance révolutionnaire européenne, had formed this terror organisation composed of several five-man groups. As Ivanov eventually left the society, other members, fearing he might turn into an informer, murdered him on 21 November 1869 in the Academy park. After hearing the news of the "Nechayev Affair", as the case was known, Dostoyevksy decided to write a novel about that contemporary revolutionary movement, Demons.

In 1871, Dostoyevsky and Anna travelled by train to Berlin. During this trip, he burnt numerous manuscripts, including those for The Idiot, because he was worried about problems when going through customs. The family arrived in St Petersburg on 8 July, marking the end of a honeymoon (originally planned to last for three months) that had lasted over four years.

Return to Russia

Back in Russia in July 1871, the family was again in financial trouble and had to sell their remaining possessions. Besides, Anna was reaching the final term of her second pregnancy. Their son, Fyodor, was born on 16 July. Soon after the birth, they moved to a different apartment near the Institute of Technology. The family hoped to cancel their large debts by selling their house in Peski, but problems with the tenant resulted in a relatively low selling price, so disputes with their creditors continued. Anna proposed that they raise money on her husband's copyrights and negotiated with the creditors to pay off their debts in instalments.

Dostoyevsky was able to revive his friendships with Maykov and Strakhov and to find new acquaintances, such as Vsevolod Solovyov, his brother Vladimir, church politician Terty Filipov and Konstantin Pobedonostsev, future Imperial High Commissioner of the Most Holy Synod, who influenced Dostoyevsky's political progression to conservatism. In early 1872, the art collector Pavel Tretyakov asked Dostoyevsky to pose for Vasily Perov. According to Danish critic Georg Brandes, Perov's painting, one of the most popular portraits of Dostoyevsky, is a depiction "half that of a Russian peasant, half that of a criminal". Around this time, the Dostoyevskys planned their holidays in Staraya Russa, a town known for its mineral spa. Lyuba had injured her wrist a few weeks before, so Anna returned to St Petersburg with her while Dostoyevsky waited with their son in Staraya Russa for their return. Shortly afterwards, Anna's sister died from typhus and Anna developed an abscess on her throat. Dostoyevsky's work on his next novel was consequently delayed.

The family returned to St Petersburg in September 1872. The Demons (also known as The Possessed or The Devils) was finished on 26 November 1872 and released in January by the "Dostoyevsky Press", founded by Dostoyevsky and his wife. Although they only accepted cash payments and the bookshop was their own apartment, the business was successful: about 3,000 copies of The Demons were sold. Anna was in charge of the financing. Dostoyevsky proposed that they establish a new periodical, A Writer's Diary, which would include a collection of essays of the same name, but due to lack of money it had to be published in Vladimir Meshchersky's The Citizen, beginning on 1 January in return for a salary of 3,000 rubles per year. In the summer of 1873, Anna travelled again with her children to Staraya Russa, while Dostoyevsky stayed in St Petersburg to continue with his Diary.

In March 1874, Dostoyevsky left The Citizen because of the stressful nature of the work and interference from the Russian bureaucracy. In his fifteen months with The Citizen, he was brought to court twice: on 11 June 1873, for citing the words of prince Meshchersky without permission, and again on 23 March 1874. Dostoyevsky offered to sell The Russian Messenger a new novel he had not yet begun to write, but the magazine refused to give him the sum he had asked for. Nikolay Nekrasov suggested that he publish A Writer's Diary in The National Annals; he would receive 250 rubles for each printer's sheet, 100 more than from The Russian Messenger. Dostoyevsky's health began to decline, and he started to experience the first symptoms of a lung disease. He consulted several doctors in St Petersburg and was advised to take a cure outside Russia. Around July, Dostoyevsky reached Ems but went to a different physician, who diagnosed him with acute catarrh. During his stay at the health spa he began to work on The Adolescent, also known as The Raw Youth. In late July he returned to St Petersburg.

His wife proposed that they spend the winter in Staraya Russa to give him a rest from his work, although doctors had suggested that Dostoyevsky make a second visit to Ems because his health had improved since his last visit. On 10 August 1875, in Staraya Russa, his son Alexey was born. In mid-September the family returned to St Petersburg. Dostoyevsky finished The Adolescent at the end of 1875, although passages of it had been serialised since January in the Annals. The Adolescent chronicles the life of a 19-year-old intellectual, Arkady Dolgoruky, the illegitimate child of a controversial and womanising landowner named Versilov and a peasant mother. A main theme in the novel is the recurring conflict between father and son – particularly about different ideologies – representing battles between the conventional "old" way of thinking in the 1840s and the new nihilistic view of the youth of 1860s Russia.

Last years

In early 1876 Dostoyevsky continued to work on his Diaries. The book includes his classic works, composition books, sketches, drafts, letters, autographs and committed thoughts, and encompasses various different social, religious, political and ethical themes. This essay collection sold over twice as much as his previous books. Dostoyevsky received more letters from readers than ever before, and people of all ages and occupations visited him. Thanks to Anna's brother, the family could finally buy a dacha in Staraya Russa. In the summer of 1876, Dostoyevsky began experiencing breathlessness again. He visited Ems for a third time, was prescribed a similar remedy as before and was told that he might live for another 15 years should he move to a more healthy climate. When Dostoyevsky returned to Russia, Tsar Alexander II ordered him to visit his palace and to present Diaries to him, and asked that Dostoyevsky educate his sons, Sergey and Paul. This visit led to the increase of his circle of acquaintances. He was a frequent guest in several salons in St Petersburg and met many famous people, Princess Sofya Tolstaya, the poet Yakov Polonsky, the politician Sergei Witte, the journalist Alexey Suvorin, the musician Anton Rubinstein and the artist Ilya Repin among them.

Dostoyevsky's health began to deteriorate further, and in March 1877 he had four epileptic seizures. Instead of going back to Ems he decided to visit Maly Prikol, a manor near Kursk. On the way back to St Petersburg to finalise his Diaries, Dostoyevsky visited Darovoye, where he had spent much of his childhood. At the same time Anna and her children made a pilgrimage to Kiev. In December he attended Nikolay Nekrasov's funeral and gave a speech. He was also appointed an honorary member of the Russian Academy of Sciences. In early 1878 he heard a speech about the "God-man" delivered by Vladimir Solovyov, which set him thinking about his next novel. In February 1879 he received an honorary certificate from the academy. He declined the invitation to an international congress about copyright in Paris after his son Alyosha had an extreme epileptic seizure and died on 16 May. The family later moved to the apartment where Dostoyevsky had written his first works. Around this time he was elected to the board of directors of the Slavic Benevolent Society in St Petersburg, and that summer he was elected to the honorary committee of the Association Littéraire et Artistique Internationale, which included Victor Hugo, Ivan Turgenev, Paul Heyse, Alfred Tennyson, Anthony Trollope, Henry Longfellow, Ralph Waldo Emerson and Leo Tolstoy. Dostoyevsky made his fourth and final visit to Ems in early August 1879. He was diagnosed as having early-stage pulmonary emphysema. His doctor believed that although his disease could not be cured, it could be successfully managed.

At nearly 800 pages, The Brothers Karamazov is Dostoyevsky's largest literary work. It received both critical and popular acclaim and is often cited as his magnum opus. Composed of 12 books, The Brothers Karamazov tells the story of the three protagonists: the novice Alyosha Karamazov, the non-believer Ivan Karamazov and the soldier Dmitry. First parts of the books introduces the Karamazovs. The main plot is the death of their father Fyodor, while other parts are philosophical and religious argumentations by Father Zosima to Alyosha. The most renowned chapter is "The Grand Inquisitor", a parable told by Ivan to Alyosha about Christ's Second Coming in Seville, Spain, where Christ was imprisoned by the ninety-years old, pseudo-religious, Catholic Grand Inquisitor. Instead of answering him, Christ gives him a kiss and the Inquisitor subsequently releases him but tells not to return. Critics, such as D. H. Lawrence, misunderstood the tale by stating that Dostoyevsky defended the Inquisitor's actions, while others, such as Romano Guardini, argued that the book's Christ was Ivan's own interpretation of Christ, "the idealistic product of the unbelief". Ivan, however, obviously stated that he is against Christ. Most contemporary critics and scholars agree that Dostoyevsky is particularly attacking Roman Catholicism and socialist atheism, which both represent the Inquisitor. Dostoyevsky warns the readers against a revelation in the future which already occurred in the past; for him, the Donation of Pepin around 750 and the Spanish Inquisition in the 16th century corrupted true Christianity. The first parts of the novel were serialised in The Russian Messenger from 1 February and the final sections were published in November 1880.

On 3 February 1880, Dostoyevsky was chosen as the vice president of the Slavic Benevolent Society, and was invited to speak at the unveiling of the Pushkin memorial in Moscow. Dostoyevsky delivered his speech from memory two days later, inside a large room, giving an impressive performance that had great emotional impact on many in his audience. His speech was met with thunderous applause, and even his long-time rival Ivan Turgenev embraced him. Dostoyevsky's speech was later attacked by several people. For example, the liberal political scientist Alexander Gradovsky thought that he idolised the people in his speech, and conservative thinker Konstantin Leontiev, in his essay "On Universal Love", compared the speech with French Utopian socialism rather than Christianity. However, Leontiev praised Dostoyevsky's last novel, stating that it features no "rosy Christianity". These attacks led to a further deterioration of Dostoyevsky's health.

– Lyubov Dostoyevskaya

On 25 January, the Tsar's secret police, while searching for members of the terror organisation Narodnaya Volya ("The People's Will") who had assassinated Tsar Alexander II, executed a search warrant in the apartment of one of Dostoyevsky's neighbours. Anna denied that this might have been the cause for Dostoyevksy's pulmonary haemorrhage on 26 January 1881, saying that it occurred after her husband had been searching for a dropped pen holder. The haemorrhage may have also been caused by the heavy disputes with his sister Vera about his aunt Aleksandra Kumanina's estate, which was agreed upon on 30 March and discussed in the St Petersburg City Court on 24 July 1879. His wife would later acquire a part of the estate of ca. 185 desiatina (around 500 acres or 202 ha) of forest and 92 desiatina (around 250 acres or 101 ha) of farmland. Following another haemorrhage Anna called the doctors, who gave a grim prognosis. A third haemorrhage followed shortly afterwards.

Among Dostoyevsky's last words was his citation of Matthew 3:14: "But John forbad him, saying, I have need to be baptized of thee, and comest thou to me? And Jesus answering said unto him, Suffer it to be so now: for thus it becometh us to fulfil all righteousness" and finishing with "Hear now—permit it. Do not restrain me!". According to a Russian custom, his body was placed on a table. Dostoyevsky was interred in the Tikhvin Cemetery at the Alexander Nevsky Convent, near his favourite poets Karamsin and Zhukovsky. It is not exactly known how many visitors attended his funeral. According to a reporter, more than 100,000 mourners were there, while others state a number between 40,000 and 50,000. His burial attracted many prominent people. Nestor, archbishop of Vyborg, delivered the liturgy, while Ioann Yanyshev performed the consecration. His tombstone is inscribed with these words of Christ from the New Testament:

Verily, verily, I say unto you, Except a corn of wheat fall into the ground and die, it abideth alone: but if it die, it bringeth forth much fruit.

— Jesus, from the Gospel According to John 12:24

Personal life

Affairs

Dostoyevsky had his first known affair with Avdotya Yakovlevna, the wife of Panayev. He met her in the Panayev circle in the early 1840s. She was described as educated, interested in literature and a femme fatale. However, Dostoyevsky later admitted that he "fell hopelessly in love with Panayeva, I'm over it now, but I'm not sure". According to Dostoyevskaya in her memoirs, Dostoyevsky once asked his sister's sister-in-law, Yelena Ivanova, whether she would marry him (as her husband was deathly ill), but she denied his proposal.

Another short but intimate affair was with Polina Suslova, which peaked in the winter of 1862–63 and decreased the following years. Suslova's infidelity with a Spaniard in late spring and Dostoyevsky's gambling addiction and age resulted in the end of their relationship. He later described her in a letter to Nadezhda Suslova as a "great egoist. Her egoism and her vanity are colossal. She demands everything of other people, all the perfections, and does not pardon the slightest imperfection in the light of other qualities that one may possess", and later stated "I still love her, but I do not want to love her any more. She doesn't deserve this love..." Around this time, his first wife, Maria Dostoyevskaya, née Isayevna, died of tuberculosis. She had previously refused his marriage proposal, stating that they were not meant for each other and that his poor financial situation precluded marriage. When Dostoyevsky later went to Kuznetsk, he discovered that she had had an affair with the 24-year-old schoolmaster Nikolay Vergunov. Despite this, Maria married Dostoyevsky in Semipalatinsk on 7 February 1857. Their family life was unhappy and she found it difficult to cope with his seizures. Describing their relationship, he wrote "Because of her strange, suspicious and fantastic character, we were definitely not happy together, but we could not stop loving each other; and the more unhappy we were, the more attached to each other we became." They mostly lived apart.

In 1865, Dostoyevsky met Anna Korvin-Krukovskaya. Their relationship was not certain: while Anna Dostoyevskaya spoke of a good affair, her sister, the mathematician Sophia, thought that Anna rejected him after a visit. Around 1866, Dostoyevsky fell in love with the stenographer Anna Snitkina, a "very young and rather nice looking twenty-year-old woman with a kind heart... I noticed that my stenographer loved me sincerely, though she never told me about it. I also liked her more and more". He later "proposed to her and... got married".

Personality and physical appearance

At 2 arshins and 6 vershoks (approximately 1.60 m or 5'2"), Dostoyevsky had a powerful personality but a less robust physical constitution. He was described by his parents as a hot-headed youngster, stubborn and cheeky. Around the time that he was at the private school in Moscow, several people depicted him as a pale, introverted dreamer and an over-excitable romantic. The most descriptive account during this time was made by a Dr Alexander Riesenkampf: "Feodor Mikhailovich was no less-good natured and no less courteous than his brother, but when not in a good mood he often looked at everything through dark glasses, became vexed, forgot good manners, and sometimes was carried away to the point of abusiveness and loss of self-awareness"; but "in the circle of his friends he always seemed lively, untroubled, self-content".

As recorded by Baron Wrangel: "He looked morose. His sickly, pale face was covered with freckles, and his blond hair was cut short. He was a little over average height and looked at me intensively with his sharp, gray-blue eyes. It was as if he were trying to look into my soul and discover what kind of man I was". Herzen characterised Dostoyevsky as "a naive, not entirely lucid, but very nice person".

After her first meeting with Dostoyevsky, Anna Snitkina described him in this manner: " was of average height, and he held himself erect. He had light brown, slightly reddish hair, he used some hair conditioner, and he combed his hair in a diligent way. I was struck by his eyes, they were different: one was dark brown; in the other, the pupil was so big that you could not see its color . The strangeness of his eyes gave Dostoyevsky some mysterious appearance. His face was pale, and it looked unhealthy..."

Epilepsy

It cannot be known for certain when Dostoyevsky's first epileptic seizure occurred. Some have proposed the age of nine, while others have argued that it was in his teens or early adulthood. Dostoyevsky, however, wrote that his first seizure happened after the "psychological torture" of the mock execution. In his notebook he recorded a total of 102 seizures in 20 years. Some have thought Dostoyevsky suffered in adulthood from generalised epilepsy, others temporal lobe epilepsy, and some a combination of these two. While Théophile Alajouanine stated that he had "partial and secondarily generalised seizures with ecstatic aura", Henri Gastaut believed that his seizures were "idiopathic generalised". P.H.A. Voskuil described "complex partial seizures with secondarily generalised nocturnal seizures and ecstatic auras". According to Rosetti and Bogousslavsky, Dostoyevsky had "temporal lobe epilepsy, most likely left mesiotemporal, with complex partial and secondarily generalised seizures, with a relatively benign course".

Sigmund Freud, the Austrian psychoanalyst who linked epilepsy with hysteria, said the illness was caused by his father's death and suggested an Oedipus complex. Freud discussed his theory of the link between epilepsy and hysteria in Dostoevsky and Parricide, a 1928 article.

Beliefs

Political

In his youth, Dostoyevsky enjoyed reading Nikolai Karamzin's History of the Russian State, which praised conservatism and the independence of Russia from other countries, ideas that Dostoyevsky would embrace in his late adulthood. Before his arrest for participating in the Petrashevsky circle in 1849, Dostoyevsky remarked, "As far as I am concerned, nothing was ever more ridiculous that the idea of a republican government in Russia". In an 1881 edition of his Diaries, Dostoyevsky stated that the tsar and the people should form a unity: "For the people, the tsar is not an external power, not the power of some conqueror... but a power of all the people, an all-unifiying power the people themselves desired".

While critical of serfdom, Dostoyevsky was sceptical about the creation of a constitution, a concept he viewed as unrelated to Russia's history, a mere "gentleman's rule", and affirmed that "a constitution would simply enslave the people". He advocated for social change instead, for the forming of a connection between the peasantry and the affluent classes. Dostoyevsky believed in an utopian Christianized Russia where "if everyone were actively Christian, not a single social question would come up ... If they were Christians they would settle everything". He thought democracy and oligarchy poor systems, as exemplified by the French current state of affairs: "the oligarchs are only concerned with the interest of the wealthy; the democrats, only with the interest of the poor; but the interests of society, the interest of all and the future of France as a whole—no one there bothers about these things." He maintained that political parties ultimately lead to social discord. In the 1860s he discovered Pochvennichestvo, a movement similar to Slavophilism in that it rejected Europe's culture and contemporary philosophical movements like nihilism and materialism. Unlike Slavophilism, however, it did not intend to establish an isolated Russia, but a more open Peter the Great state.

In his incomplete article "Socialism and Christianity", Dostoyevsky considered that civilisation ("the second stage in human history") was degraded, moving towards liberalism and losing its faith in God. He asserted that the traditional concept of Christianity should therefore be recovered. He felt contemporary western Europe "rejected the single formula for their salvation that came from God and was proclaimed through revelation to humanity, 'Thou shalt love they neighbour as thyself', and replaced it with practical conclusions such as, 'Chacun pour soi et Dieu pour tous' ("Every man for himself and God for all"), or scientific slogans like 'the struggle for survival'". This crisis was the consequence of the collision between communal and individual interests, brought about by a decline in religious and moral principles.

Dostoyevsky also differentiated three "enormous world ideas" prevailing in his time:

- Catholicism, which continued the tradition of Imperial Rome and had thus become anti-Christian and proto-socialist inasmuch as the Church's interest in political and mundane affairs made it leave behind the idea of Christ. For Dostoyevsky, socialism was "the latest incarnation of the Catholic idea" and its "natural ally"".

- Protestantism, which, while colliding with Catholicism, was none better than it as its doctrine was self-contradictory and would ultimately lose power and spirituality

- the Russian or Slavic idea, grounded in Russian Orthodoxy, which he deemed the ideal Christianity.

During the Russo-Turkish War (1877–1878), Dostoyevsky asserted that war may be necessary if salvation were granted. He wanted to eliminate the Muslim Ottoman Empire and retrieve the Christian Byzantian Empire. Furthermore, he hoped for the liberation of Balkan Slavs and its unification with the Russian Empire.

Religious

Dostoyevsky was raised in a "pious Russian family" and knew the Gospel "almost from the cradle". He was introduced to Christianity through the Russian translation of Johannes Hübner's One Hundred and Four Sacred Stories from the Old and New Testaments Selected for Children (partly a German bible for children and partly a catechism), attended Liturgy every Sunday from an early age and took part in annual pilgrimages to the St Sergius Trinity Monastery. Apart from his spiritual upbringing at home, Dostoyevsky was also educated by a deacon who lived near the hospital. Among his most cherished childhood memories were the prayers he used to say in front of guests and a reading from the Book of Job, which "made an impression on " when "still almost a child".

According to an officer at the military academy, Dostoyevsky was profoundly religious, followed the precepts of the Orthodox Church and would regularly read the Gospels and Heinrich Zschokke's Die Stunden der Andacht ("Hours of Devotion"), which "preached a sentimental version of Christianity entirely free from dogmatic content and with a strong emphasis on giving Christian love a social application". This book was, perhaps, what prompted his later interest in Christian socialism. Through the literature of Hoffmann, Balzac, Sue and Goethe, Dostoyevsky created his own belief system, similar to Russian sectarianism and Old Belief. After his arrest, the mock execution and the subsequent imprisonment in Siberia, he focused intensely on the figure of Christ and the New Testament, the only book allowed in prison. In January 1854, Dostoyevsky wrote the following letter to the woman who had sent him the Testament:

I have heard from many sources that you are very religious, Natalia Dmitrievna ... As for myself, I confess that I am a child of my age, a child of unbelief and doubt up to this moment, and I am certain that I shall remain so to the grave. What terrible torments this thirst to believe has cost me and continues to cost me, burning ever more strongly in my soul the more contrary arguments there are. Nevertheless, God sometimes sends me moments of complete tranquility. In such moments I love and find that I am loved by others, and in such moments I have nurtured in myself a symbol of truth, in which everything is clear and holy for me. This symbol is very simple: it is the belief that there is nothing finer, profounder, more attractive, more reasonable, more courageous and more perfect than Christ, and not only is there not, but I tell myself with jealous love that there cannot be. Even if someone were to prove to me that the truth lay outside Christ, I should choose to remain with Christ rather than with the truth.

— Fyodor Dostoyevsky, Pisma, XXVIII, i, p. 176

In Semipalatinsk, Dostoyevsky revived his trust in God by frequently looking at the star-studded sky. Wrangel said that he was "rather pious, but did not often go to church, and disliked priests, especially the Siberian ones. But he spoke about Christ ecstatically". Both planned to translate Hegel's works and Carus' Psyche. Dostoyevsky explored Islam too, after asking his brother to send him a copy of the Quran. Two pilgrimages and two works by Dmitri Rostovsky, the archbishop who influenced Ukrainian and Russian literature by composing groundbreaking religious plays, strengthened his beliefs. Through his visits to western Europe and discussions with Herzen, Grigoriev and Strakhov, Dostoyevsky discovered the Pochvennichestvo movement and the theory that the Catholic Church had adopted the principles of rationalism, legalism, materialism and individualism from ancient Rome and passed on its philosophy to Protestantism and consequently to socialism, which becomes atheistic.

Dostoyevsky's real beliefs remain nevertheless uncertain, since he never stated his faith explicitly. One exception might be his response, in April 1876, to a question about a suicide in Diary of a Writer, remarking that he was a "philosophical deist" – this was a quote from The Adolescent, though he did not say that it was. Two months later, however, Dostoyevsky wrote in his Diaries that his heroine George Sand "died a deisté, firmly believing in God and in the immortality of the soul". But deists at that time held different beliefs about the immortality of the soul. Besides, his belief in doctrines such as the Trinity – clearly discussed in The Brothers Karamazov, for example – suggests that he did not thoroughly understand the meaning of this term. In January that year, Dostoyevsky attended a spiritistic séance of a woman, whose name is not explicitly known. He was sceptical towards the practice, but nevertheless showed interest. When she visited the family for the last time, Fyodor welcomed her grimly: "You came in vain, I don't want to talk about spiritism." Dostoyevsky viewed spiritism as fantasy, and talked about it very critically in the article "Spiritiualism. Something about Devils. The Extraordinary Cleverness of Devils, If Only These Are Devils" in his Diaries.

Overall, many critics have pointed out that Dostoyevsky's religion is unusual and partially at odds with the Christian dogma. Malcolm V. Jones has found elements of Islam and Buddhism in his religious convictions.

Themes and style

Dostoyevsky was a representative of literary realism, a genre which depicted contemporary life and society "as they were". He saw himself as a "fantastic realist", while Apollon Grigoryev called him a "sentimental naturalist". Dostoyevsky was described as "an explorer of ideas"; his life "coincided with a particularly tumultuous period in Russian history, and was undoubtedly shaped by the sociopolitical happenings he witnessed". Beside his writings on human psychology and religion, Dostoyevsky was known for his frequent use of satire; critic Harold Bloom stated that "satiric parody is the center of Dostoyevsky's art."

Dostoyevsky's use of space and time were analysed by philologist Vladimir Toporov, who stated that "the unexpected not only is possible but also always happens". Toporov compares time and space in Dostoyevsky with film scenes: the Russian word vdrug (suddenly) appears 560 times in the Russian edition of Crime and Punishment, and provides the reader with impressions of tension, inequality and nervousness, all characteristic elements of the structure of his books. Dostoyevsky's works often utilise extremely precise numbers (at two steps..., two roads to the right), as well as high and rounded numbers (100, 1000, 10000). Critics such as Donald Fanger and Roman Katsman, writer of The Time of Cruel Miracles: Mythopoesis in Dostoevsky and Agnon, call these elements "mythopoeic". Dostoyevsky's characters' growth occurs through repetition, events, and memory, despite how painful they may be for the characters.

Dostoyevsky investigated human nature. According to his good friend, the Russian philosopher Nikolay Strakhov, "All his attention was directed upon people, and he grasped at only their nature and character", because he was "interested by people, people exclusively, with their state of soul, with the manner of their lives, their feelings and thoughts". Philosopher and Dostoyevsky researcher Nikolai Berdyaev stated that he "is not a realist as an artist, he is an experimentator, a creator of an experimential metaphysics of human nature". His characters live in an unlimited, irrealistic world, beyond borders and limits. Berdyaev remarks that "Dostoevsky reveals a new mystical science of man", limited to people "which have been drawn into the whirlwind".

Dostoyevsky's works explore irrational dark motifs, dreams, emotions and visions, all typical elements of Gothic fiction. He was an avid reader of the Gothic and enjoyed the works of Ann Radcliffe, Balzac, Hoffmann, Charles Maturin and Soulié. Among his first Gothic works was "The Landlady". The stepfather's demonic fiddle and the mysterious seller in Netochka Nezvanova are Gothic-like. In Humiliated and Insulted, the villain has a typical demonic appearance. Other roots of this genre can be found in Crime and Punishment; for example the dark and dirty rooms and Raskolnikov's Mephistophelian character, or the vampire-like Nastasia Filippovna in The Idiot and femme-fatale Katerina Ivanovna in The Brothers Karamazov.

Russian literary critic Mikhail Bakhtin highlights Dostoyevsky's use of literary polyphony, where independent, equal voices speak for an individual self, in a context in which they can be heard, flourish and interact together, which he calls "carnivalesque". Many of Dostoyevsky's works have elements of menippean satire, which he most likely revived as a genre, and which combines comedy, fantasy, symbolism and adventure and in which mental attitudes are personified. A Writer's Diary and "Bobok" are "one of the greatest menippeas in all world literature", but examples can be found in "The Dream of a Ridiculous Man", the first encounter between Raskolnikov and Sonja in Crime and Punishment, which is "an almost perfect Christianised menippea", and in "The Legend of the Grand Inquisitor".

Suicides are found in several of Dostoyevsky's books. The 1860s–1880s marked a near-epidemic period of suicides in Russia, and many contemporary Russian authors wrote about suicide. Dostoyevsky's suicide victims are unbelievers and models of the "new man": the Underground Man in Notes from Underground, Raskolnikov in Crime and Punishment, Ippolit in The Idiot, Kirillov in The Demons, and Ivan Karamazov and Smerdiakov in The Brothers Karamazov. Disbelief in God and immortality and the influence of contemporary philosophies such as positivism and materialism are seen as important factors in the development of the characters' suicidal tendencies. Dostoyevsky felt that a belief in God and immortality was necessary for human existence.

Early writing

Dostoyevsky's early works were influenced by contemporary writers, including Pushkin, Gogol and Hoffmann, which led to accusations of plagiarism. Several critics pointed out similarities in The Double to Gogol's works The Overcoat and The Nose. Parallels have been made between his short story "An Honest Thief" and George Sand's François le champi and Eugène Sue's Mathilde ou Confessions d'une jeune fille, and between Dostoyevsky's Netochka Nezvanova and Charles Dickens' Dombey and Son. Like many young writers, he was "not fully convinced of his own creative faculty, yet firmly believed in the correctness of his critical judgement."

Dostoyevsky's translations of Balzac's Eugénie Grandet and Sand's La dernière Aldini differ from standard translations. In his translation of Eugénie Grandet, he often omitted whole passages or paraphrased significantly, perhaps because of his rudimentary knowledge of French or his haste. He also used darker words, such as "gloomy" instead of "pale" and "cold", and sensational adjectives, such as "horrible" and "mysterious". The translation of La desnière Aldini was never completed because someone already published one in 1837. He also abandonded working on Mathilde by Eugène Sue due to lack of funds. Influenced by the plays he watched during this time, he wrote verse dramas for two plays, Mary Stuart by Schiller and Boris Godunov by Pushkin, which have been lost.

Dostoyevsky's debut novel, Poor Folk, describes in the form of an epistolary novel the relationship between the elderly official Makar Devushkin and the young seamstress Varvara Dobroselova, a remote relative. They write letters to each other and through the tender, sentimental adoration for his relative and her confident, warm friendship with him, they seem to prefer a life in a higher society, although it forced them into poverty. Critic Vissarion Belinsky called the novel "Russia's first social novel", favourising the depiction of poor and downtrodden people. Dostoyevsky's success would not continue with his next work, The Double, which centres on a shy protagonist Yakov Golyadkin, who discovers how his doppelgänger, who has achieved the success denied to him, has slowly destroyed his life. The novel was panned by critics and readers alike; Belinsky commented that the work had "no sense, no content and no thoughts", and that the novel was boring due to the protagonist's garrulity, or tendency towards verbal diarrhoea. He and other critics stated that the idea for The Double was brilliant, but that its external form was misconceived and full of multi-clause sentences.

The short stories Dostoyevsky wrote after this period but before prison have similar themes as Poor Folk and The Double. For example, his short story "White Nights", which "features rich nature and music imagery, gentle irony, usually directed at the first-person narrator himself, and a warm pathos that is always ready to turn into self-parody". The first three parts of his unfinished novel Netochka Nezvanova chronicle the trials and tribulations of Netochka, stepdaughter of a second-class fiddler, and in "A Christmas Tree and a Wedding", Dostoyevsky switches to social satire.

Later years

After his release from prison, Dostoyevsky's writing style changed drastically, moving away from the "sentimental naturalism" of Poor Folk and The Insulted and Injured, towards more psychological and philosophical themes. Even though he spent four years in prison in poor conditions, Dostoyevsky wrote two humorous books; the novella Uncle's Dream and the novel The Village of Stepanchikovo. The novel Notes From the Underground, which he partially wrote in prison, was his first secular book, with few references to religion. Later, he wrote about his reluctance to remove religious themes from the book, stating, "The censor pigs have passed everything where I scoffed at everything and, on the face of it, was sometimes even blasphemous, but have forbidden the parts where I demonstrated the need for belief in Christ from all this".

Critics have speculated that Dostoyevsky's concern with the downtrodden after the publication of Notes from the Underground was "motivated not so much by compassion as by an unhealthy curiosity about the darker recesses of the human psyche, ... by a perverse attraction to the diseased states of the human mind, ... or ... by sadistic pleasure in observing human suffering". Humiliated and Insulted was similarly secular; only at the end of the 1860s, beginning with the publication of Crime and Punishment, did Dostoyevsky's religious themes resurface.

The House of the Dead is a semi-autobiographical memoir written while Dostoyevsky was in prison and includes a few religious themes. Characters from the three Abrahamic religions – Judaism, Islam and Christianity– appear in it, and while the Jewish character Isay Fomich and characters affiliated with the Orthodox Church and the Old Believers are depicted negatively, the Muslims Nurra and Aley from Dagestan are depicted positively. Aley is later educated by reading the Bible, and shows a fascination for the altruistic message in Christ's Sermon on the Mount, which he views as the ideal philosophy.

Dostoyevsky's later works are characterised by autobiographical elements. According to Norwegian Slavist and vice president of the International Dostoevsky Association, Geir Kjetsaa, "Dostoyevsky's life is a novel". The Idiot, perhaps Dostoyevsky's most autobiographical work, has many similarities to his life; for example, the viewing of Holbein's painting The Body of the Dead Christ in the Tomb, Prince Myshkin's skilled handwriting and similarities between he and his characters.

The works Dostoyevsky published in the 1870s explore human beings' capacity for manipulation. The Eternal Husband and "The Meek One" describe the relationship between a man and woman in marriage, the first chronicling the manipulation of a husband by his wife; the latter the opposite. "The Dream of a Ridiculous Man" raises this theme of manipulation from the individual to a metaphysical level. Philosopher Nikolay Strakhov agreed, saying that Dostoyevsky was "a great thinker and a great visionary... a dialectician of genius, one of Russia's greatest metaphysicians."

Philosophy

Dostoyevsky's works were often called "philosophical" despite his lack of knowledge about philosophy; he described himself as "weak in philosophy". "Fyodor Mikhailovich loved these questions about the essence of things and the limits of knowledge", Strakhov wrote. Although theologian George Florovsky described Dostoyevsky as a "philosophical problem" because it is unknown whether Dostoyevsky believed in what he wrote, many philosophical thoughts are found in books such as A Writer's Diary and The Brothers Karamazov because he often wrote in the first person. He might have been critical of rational and logical thinking because he was "more a sage and an artist than a strictly logical, consistent thinker." He represented Kierkegaardian irrationalism, in works such as House of the Dead, Notes from Underground, Crime and Punishment and Demons. His irrationalism is mentioned in William Barrett's Irrational Man: A Study in Existential Philosophy and in Walter Kaufmann's Existentialisms from Dostoevsky to Sartre.

Style

Strakhov, a close friend of Dostoyevsky's, described his writing habits: " wrote late at night. Around midnight, when the whole house went to bed, he stayed alone, with his samowar, drinking not very strong, but almost cold tea, and writing until five or six o'clock in the morning. He got up around two or three o'clock in the afternoon." The lazy but hardworking Dostoyevsky wrote as fast as possible as he needed money badly. He also postponed the writing to the last possible day and only wrote when he had enough time to finish his work. It is not surprising that he often exceeded the time limit. Dostoyevsky was known for his artistic writing. Grigorovich defined his letters as beads from a necklace. He only knew one person who could write in such a manner: Thomas-Alexandre Dumas.

Criticism

Dostoyevsky's work has not always met positive receptions. Several critics, such as Nikolay Dobrolyubov, Ivan Bunin and Vladimir Nabokov, found that even if his writing successfully explored psychological and philosophical themes, its artistic quality was "below criticism". Others found fault in chaotic and disorganised plots, whereas others, like Turgenev, in "excessive psychologising" or in an overdetailed naturalism. His characters were called "unrealistic, schematic and contrived". His style was deemed "prolix, repetitious and lacking in polish, balance, restraint and good taste". The Idiot, The Possessed and The Brothers Karamazov were criticised for including unrealistic characters by critics such as Saltykov-Shchedrin, Tolstoy and Mikhailovsky. Its characters were described as "puppets" and "pale, pretentious and artificial", which is not what should be found in realism literature. The puppet-like feature was compared with that of Hoffmann's characters, an author Dostoyevsky admired.

Basing his estimation on a stated criteria of enduring art and individual genius, Nabokov judged Dostoyevsky as "not a great writer, but rather a mediocre one – with flashes of excellent humour but, alas, with wastelands of literary platitudes in between." Compiling a list he demonstrates and complains that the novels are peopled by "neurotics and lunatics" and notes that Dostoyevsky's characters do not develop: "We get them all complete at the beginning of the tale and so they remain." He finds the novels full of contrived "surprises and complications of plot", which when first read are effective. On a second reading, though, and without the shock and benefit of these surprises, the books appear loaded with "glorified cliché".

Legacy

Together with Leo Tolstoy, Dostoyevsky is often regarded as one of the greatest and most influential novelists of the Golden Age of Russian literature. His debut novel, Poor Folk, pushed him into the literary mainstream. Critics saw him as a rising star of Russian literature. He was known for his gifted narrative: according to Konstantin Staniukovich in his essay "The Pushkin Anniversary and Dostoevsky's Speech" from Business, "the language of Dostoevsky's really looks like a sermon. He speaks with the tone of a prophet. He makes a sermon like a pastor; it is very deep, sincere, and we understand that he wants to impress the emotions of his listeners."

Dostoyevsky's works also attracted readers outside Russia. The German translator Wilhelm Wolfsohn published one of the first translations, parts of Poor Folk, in an 1846–1847 magazine, and a French translation followed. The first English translations were provided by Marie von Thilo in 1881, and the first acclaimed translations into English were produced between 1912 and 1920 by Constance Garnett. Friedrich Nietzsche called Dostoyevsky "the only psychologist, incidentally, from whom I had something to learn; he ranks among the most beautiful strokes of fortune in my life". Thomas Mann recommended reading his novels in their entirety. Hermann Hesse enjoyed Dostoyevsky's work and also cautioned against that to read him is like a "glimpse into the havoc". The Norwegian novelist Knut Hamsun wrote that "no one has analysed the complicated human structure as Dostoyevsky. His psychologic sense is overwhelming and visionary. We have no yardstick by which to assess his greatness". André Gide said that Dostoyevsky "should be put beside Ibsen and Nietzsche; he is equal in size to these three, and maybe the most important".

In a letter to Gide, Edmund Gosse said that Dostoyevsky is "the cocaine and morphia of modern literature". Ernest Hemingway acknowledged Dostoyevsky as one of his influences. In his posthumously published collection of sketches A Moveable Feast, Hemingway stated that in Dostoevsky "there were things believable and not to be believed, but some so true that they changed you as you read them; frailty and madness, wickedness and saintliness, and the insanity of gambling were there to know." According to Arthur Power's Conversations with James Joyce, Joyce praised Dostoyevsky's prose: "(...) he is the man more than any other who has created modern prose, and intensified it to its present-day pitch. It was his explosive power which shattered the Victorian novel with its simpering maidens and ordered commonplaces; books which were without imagination or violence." In her essay The Russian Point of View, Virginia Woolf said, "The novels of Dostoevsky are seething whirlpools, gyrating sandstorms, waterspouts which hiss and boil and suck us in. They are composed purely and wholly of the stuff of the soul. Against our wills we are drawn in, whirled round, blinded, suffocated, and at the same time filled with a giddy rapture. Out of Shakespeare there is no more exciting reading". Franz Kafka named Dostoyevsky as his "blood-relative", and was heavily influenced by his works, especially The Brothers Karamazov and Crime and Punishment, both of which had a profound effect on The Trial. Sigmund Freud called his last work "the most significant novel ever written". Modern cultural movements such as the surrealists, the existentialists and the Beats regard Dostoyevsky as an influence. Dostoyevsky is cited as the forerunner of Russian symbolism, existentialism, expressionism and psychoanalysis.

After the 1917 Russian Revolution, Dostoyevsky's books were often censored or banned. His philosophy, especially in The Demons, was deemed capitalistic and anti-Communist, leading Maxim Gorky to nickname the author "our evil genius". Reading Dostoyevsky was forbidden, and those who did not observe this rule were imprisoned. During the Second World War, however, his works were used as propaganda by both the Soviets and the Nazis. After the war, the prohibition law in the Soviet Union was overturned. Even though the 125th anniversary of his birth was celebrated throughout Russia in 1947, his works were banned again until Nikita Khrushchev's accession to power ten years later, following de-Stalinization and a softening of repressive laws. In the second half of the twentieth century, his works topped the best-seller lists worldwide. Many of his novels and short stories were filmed and dramatised in the Soviet Union and other countries. Dostoyevsy's fictional characters and his work overall were popularised in vaudevilles, films and plays.

In 1956 an olive-green postage stamp dedicated to Dostoyevsky was released in the Soviet Union with a print run of 1,000 copies. A Dostoevsky Museum was opened on 12 November 1971 in the apartment where he wrote his first and last novels. A minor planet discovered in 1981 by Lyudmila Karachkina was named 3453 Dostoevsky. Viewers of the TV show Name of Russia voted him the ninth greatest Russian of all time, behind chemist Dmitry Mendeleev and ahead of ruler Ivan IV. A Moscow Metro station on the Lyublinsko-Dmitrovskaya Line was scheduled to open to the public on 15 May 2010, the 75th anniversary of the Moscow Metro. Illustrations on the décor made by artist Ivan Nikolaev were criticised because of their depiction of suicides, but did not hinder the opening of Dostoyevskaya on 19 June.

Four of Dostoyevsky's books (Crime and Punishment, The Possessed, The Idiot and The Brothers Karamazov) are on the list of Norwegian Book Club's 100 best books of all time.

Works

Dostoyevsky's works of fiction include 15 novels and novellas, 17 short stories, and 5 translations. Many of his longer novels were first published in serialised form in literary magazines and journals (see the individual articles). The years given below indicate the year in which the novel's final part or first complete book edition was published. In English many of his novels and stories are known by different titles.

Plays

- (~1844) The Jew Yankel (unknown whether finished or not; title based on Gogol's character from Taras Bulba)

|

Novels and novellas

|

Short stories

|

Essays

- Winter Notes on Summer Impressions (1863)

- A Writer's Diary (1873–1881)

- Letters (collected in English translations in five volumes of Complete Letters)

Translations

- (1843) Eugénie Grandet (Honore de Balzac)

- (1843) La dernière Aldini (George Sand)

- (1843) Mary Stuart (Friedrich Schiller)

- (1843) Boris Godunov (Alexander Pushkin)

References

Notes

- 1. His name has been variously transcribed into English, his first name sometimes being rendered as Theodore or Fedor. Before the post-revolutionary orthographic reform which, among other things, replaced the Cyrillic letter Ѳ ('th') with the Cyrillic letter Ф ('f'), Dostoyevsky's name was written Ѳеодоръ (Theodor) Михайловичъ Достоевскій.

- 2. Old Style date 30 October 1821 – 28 January 1881

- 3. The brother of Eduard Totleben, to whom Dostoyevsky would later appeal for his release from the military after prison.

- 4. The actual reason, which they kept secret from him, was that the periodical had already arranged to publish Leo Tolstoy's Anna Karenina.

- 5. Nicholas I supported the technical university, which provided the opportunity for a good professional military career.

- 6. Lyubov later called herself Aimée (French for "beloved").

- 7. Time magazine was a popular periodical, with more than 4,000 subscribers before it was closed on 24 May 1863, by the Tsarist Regime due to its publication of an essay by Nikolay Strakhov about the Polish revolt in Russia. Time and its 1864 successor Epokha expressed the philosophy of the conservative and Slavophile movement Pochvennichestvo, supported by Dostoyevsky during his term of imprisonment and in his post-prison years.

Footnotes

- "Russian literature". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 11 April 2008.

Dostoyevsky, who is generally regarded as one of the supreme psychologists in world literature, sought to demonstrate the compatibility of Christianity with the deepest truths of the psyche.

- Kjetsaa 1989, p. foreword.

- ^ Kjetsaa 1989, pp. 1–5.

- ^ Frank 1979, pp. 6–22.

- Kjetsaa 1989, p. 11.

- Kjetsaa 1989, pp. 6–11.

- ^ Frank 1979, pp. 23–54.

- Kjetsaa 1989, pp. 14–5.

- Kjetsaa 1989, pp. 17–23.

- Frank 1979, pp. 69–90.

- Lantz 2004, p. 2.

- Kjetsaa 1989, pp. 24–7.

- ^ Frank 1979, pp. 69–111.

- Sekirin 1997, p. 59.

- Lantz 2004, p. 109.

- Kjetsaa 1989, pp. 31–6.

- ^ Lantz 2004, p. 3.

- Lavrin 1947, pp. 10–11.

- Kjetsaa 1989, pp. 36–7.

- Fyodor Dostoyevsky. "Letters of Fyodor Michailovitch Dostoyevsky to his family and friends". Retrieved 3 October 2012.

- Sekirin 1997, p. 73.

- Frank 1979, pp. 113–57.

- Kjetsaa 1989, pp. 42–9.

- Frank 1979, pp. 159–82.

- Kjetsaa 1989, pp. 53–5.

- Mochulsky 1967, pp. 115–21.

- Kjetsaa 1989, p. 63.

- Kjetsaa 1989, p. 59.

- Frank 1979, pp. 239–46, 259–346.

- Kjetsaa 1989, pp. 58–69.

- Mochulsky 1967, pp. 99–101.

- Mochulsky 1967, pp. 121–33.

- ^ Frank 1987, pp. 6–68.

- Kjetsaa 1989, pp. 72–9.

- Kjetsaa 1989, pp. 79–96.

- Sekirin 1997, p. 131.

- Kjetsaa 1989, pp. 96–108.

- Frank 1988, pp. 8–20.

- Sekirin 1997, pp. 107–21.

- Frank 1987, pp. 165–267.

- Kjetsaa 1989, pp. 108–13.

- ^ Frank 1987, pp. 175–221.

- Kjetsaa 1989, pp. 115–23.

- Kjetsaa 1989, pp. 126–41.

- Frank 1987, pp. 290 et seq.

- Frank 1988, pp. 8–62.

- Kjetsaa 1989, pp. 135–7.

- Frank 1988, pp. 233–49.

- Kjetsaa 1989, pp. 143–5.

- Frank 1988, pp. 197–211, 283–94, 248–365.

- Kjetsaa 1989, pp. 151–75.

- Frank 1997, p. 45.

- Frank 1997, pp. 42–183.

- Kjetsaa 1989, pp. 162–96.

- Frank 1997, pp. 151–363.

- Kjetsaa 1989, pp. 201–37.

- Kjetsaa 1989, p. 245.

- Frank 1997, pp. 188, 396.

- ^ Frank 2003, pp. 14–63.

- Kjetsaa 1989, pp. 240–61.

- Mochulsky 1967, pp. 405–06.

- Frank 1997, pp. 241–363.

- Kjetsaa 1989, p. 265.

- Kjetsaa 1989, pp. 265–7.

- Kjetsaa 1989, pp. 268–71.

- Frank 2003, pp. 38–118.

- Kjetsaa 1989, pp. 269–89.

- Frank 2003, pp. 120–47.

- Kjetsaa 1989, pp. 273–95.

- Frank 2003, pp. 149–97.

- Kjetsaa 1989, pp. 273–302.

- Frank 2003, pp. 199–280.

- Kjetsaa 1989, pp. 303–6.