This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Prioryman (talk | contribs) at 20:23, 12 February 2013 (→Castilian and Spanish rule (1462-1704): - alt texts). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 20:23, 12 February 2013 by Prioryman (talk | contribs) (→Castilian and Spanish rule (1462-1704): - alt texts)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)

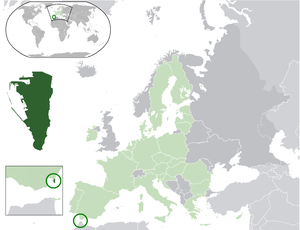

The history of Gibraltar spans over 50,000 years. Neanderthals lived there for tens of thousands of years; it may represent one of their last settlements before their extinction some 24,000 years ago. Gibraltar's recorded history began with the Phoenicians around 950 BC. The Carthaginians and Romans also visited and are said to have built shrines there, though they did not settle.

After a period of Visigothic rule following the collapse of the Roman Empire, Gibraltar was conquered by the Moors in 711 AD. The Kingdom of Castile annexed it in 1309, lost it again to the Moors in 1333 and finally regained it in 1462, after which it become part of the unified Kingdom of Spain. It remained under Spanish rule until 1704, when it was captured by an Anglo-Dutch fleet in the name of the Habsburg ruler Charles VI. Following Charles' death, Spain ceded Gibraltar to the British under the terms of the Treaty of Utrecht of 1713.

Spain subsequently sought to restore its sovereignty over Gibraltar through military, diplomatic and economic pressure. During the wars of the 18th century between Britain and Spain, Gibraltar was twice besieged and heavily bombarded but the attacks were successfully repulsed. The colony grew rapidly during the 19th and early 20th centuries, becoming one of Britain's key colonies in the Mediterranean Sea. It also became a key British naval base and stopping point for vessels en route to India via the Suez Canal. A large British naval base was constructed there at great expense at the end of the 19th century and became the backbone of Gibraltar's economy.

Gibraltar played a vital role in the Second World War by enabling the British to control the entrance to the Mediterranean. The Spanish dictator General Francisco Franco revived Spain's claim to the territory after the war. Restrictions on travel were imposed between 1969–85 and communications links with Gibraltar were severed. The Spanish claim was pursued through the United Nations under the aegis of decolonisation. Spain's position was supported by Latin American countries but was rejected by Britain and the Gibraltarians themselves, who vigorously asserted their right to self-determination. Discussions of Gibraltar's status have continued between Britain and Spain but have not reached any conclusion.

Since 1985, Gibraltar has undergone major changes as a result of post-Cold War reductions in Britain's overseas defence commitments which saw the departure of most British military forces from the territory. It has reoriented itself towards a service economy based around tourism, financial services, shipping and Internet gambling. The territory is also now fully self-governing, with its own parliament and government. Its economic success has made it one of the wealthiest parts of the European Union.

Prehistory and ancient history

Gibraltar's appearance in prehistory was very different to its modern aspect. Sea levels were much lower due to the amount of water locked up in the larger polar ice caps at the time. The peninsula was surrounded by a fertile coastal plain rather than water, with marshes and sand dunes supporting an abundant variety of animals.

Neanderthals are known to have lived in caves around the Rock of Gibraltar; in 1848 the first known adult Neanderthal skull, and only the second Neanderthal fossil ever found, was excavated at Forbes' Quarry on the north face of the Rock. The date of the skull is unclear but it has been attributed to around the start of the last glacial period about 50,000 years ago.

More Neanderthal remains have been found elsewhere on the Rock at Devil's Tower and in Ibex, Vanguard and Gorham's Caves on the east side of Gibraltar. Excavations in Gorham's Cave have found evidence of Neanderthal occupation dated as recently as 28,000-24,000 years ago, well after they were believed to have died out elsewhere in Europe. The caves of Gibraltar continued to be used by modern Homo sapiens after the final extinction of the Neanderthals. Stone tools, ancient hearths and animal bones dating from around 40,000 years ago to about 5,000 years ago have been found in deposits left in Gorham's Cave.

During ancient times, Gibraltar was regarded by the peoples of the Mediterranean as a place of religious and symbolic importance. The Phoenicians were present for several centuries, apparently using Gorham's Cave as a shrine to the genius loci of the place, as did the Carthaginians and Romans after them. Excavations in the cave have shown that pottery, jewellery and Egyptian scarabs were left as offerings to the gods, probably in the hope of securing safe passage through the dangerous waters of the Strait of Gibraltar.

The Rock was revered by the Greeks and Romans as one of the two Pillars of Hercules, created by the demigod during his tenth labour when he smashed through a mountain separating the Atlantic and the Mediterranean. According to a Phocaean Greek traveller who visited in the sixth century BC, there were temples and altars to Hercules on the Rock where passing travellers made sacrifices.

To the ancients, Gibraltar was known as Mons Calpe, a name perhaps derived from the Phoenician word kalph, "hollowed out", presumably in reference to the caves in the Rock. It was well-known to ancient geographers; however, there is no known archaeological evidence of permanent settlements from the ancient period and according to the ancient Greek traveller Euctemon, visitors to Gibraltar stayed no longer than necessary "for to remain there was sacrilege". There were more mundane reasons not to settle, as Gibraltar had many disadvantages that were to hinder later settlers; it lacked easily accessible fresh water, fertile soil, a supply of firewood or a safe natural anchorage. Its geographical location, which later became its key strategic asset, was not a significant factor in ancient times.

For these reasons the ancients declined to settle on the Gibraltar peninsula but chose instead to live at the head of the bay in what is today known as the Campo (hinterland) of Gibraltar. The town of Carteia, near where the modern Spanish town of San Roque is located today, was founded by the Phoenicians around 950 BC on the site of an early settlement of the native Turdetani people. The Carthaginians took control of the town by 228 BC and it was captured by the Romans in 206 BC. It subsequently became Pompey's western base in his campaign of 67 BC against the pirates that menaced the Mediterranean Sea at the time. Carteia appears to have been abandoned after the Vandals sacked it in 409 AD during their march through Roman Hispania to Africa.

Muslim rule (711-1309, 1333-1462)

Main article: Moorish Gibraltar

By 681 the armies of the Umayyad Caliphate had expanded from their original homeland of Arabia to conquer the whole of North Africa as well as the Middle East and large parts of West Asia, bringing Islam in their wake and converting local peoples to the new religion. The Berbers of North Africa, called Moors by the Christians, thus became Muslims. The Strait of Gibraltar gained a new strategic significance as the frontier between Muslim North Africa and Christian Spain. The Visigothic rulers of Spain were, however, split between rival contenders for the throne. This gave the Moors the opportunity to invade and pursue a course of dividing-and-conquering the Christian factions.

Following a raid in 710, a predominately Berber army under the command of Tariq ibn Ziyad crossed from North Africa in April 711 and landed somewhere in the vicinity of Gibraltar (though most likely not in the bay or at the Rock itself). Although Tariq's expedition was an outstanding success and led to the Islamic conquest of most of the Iberian peninsula, Tariq himself ended his career in disgrace. His conquest nonetheless left a long-lasting legacy for Gibraltar: Mons Calpe was renamed Djebel al-Tariq, the Mount of Tariq, subsequently corrupted into "Gibraltar".

Gibraltar was fortified for the first time in 1160 by the Almohad Sultan Abd al-Mu'min in response to the coastal threat posed by the Christian kings of Aragon and Castile. Gibraltar was renamed Djebel al-Fath (the Mount of Victory), though this name did not persist, and a fortified town named Medinat al-Fath (the City of Victory) was laid out on the upper slopes of the Rock. It is unclear how much of Medinat al-Fath was actually built, as the surviving archaeological remains are scanty.

Its defences were put to the test for the first time in 1309, when Ferdinand IV of Castile and James II of Aragon joined forces to attack the Muslim Emirate of Granada, targeting Almeria in the east and Algeciras, across the bay from Gibraltar, in the west. In July 1309 the Castilians laid siege to both Algeciras and Gibraltar. By this time the latter had a modest population of around 1,200 people, a castle and rudimentary fortifications. They proved unequal to the task of keeping out the Castilians and Gibraltar's defenders surrendered after a month.

Ferdinand gave up the siege of Algeciras the following February but held on to Gibraltar, repopulating it with Christians and ordering that a keep and dockyard be built to secure Castile's hold on the peninsula. He also issued a letter patent granting privileges to the inhabitants to encourage people to settle.

In 1315 the Moors attempted to recapture Gibraltar but were thwarted by a Castilian relief force. Eighteen years later, however, the Sultans Muhammed IV of Granada and Abu al-Hasan Ali ibn Othman of Fez allied to besiege Gibraltar with a large army and naval force. This time the king of Castile, Alfonso XI, was unable to raise a relief force for several months due to the threat of rebellions within his kingdom. The relief force eventually arrived in June 1333 but found that the starving inhabitants of Gibraltar had already surrendered to the Moors. The Castilians now found themselves having to besiege an entrenched enemy. They were unable to break through the Moorish defences and, faced with a stalemate, the two sides agreed to disengage in exchange for mutual concessions.

Abu al-Hasan refortified Gibraltar "with strong walls as a halo surrounds a crescent moon" in anticipation of renewed war, which duly broke out in 1339. His forces suffered a disastrous defeat at the Battle of Río Salado in October 1340 and fell back to Algeciras. The Castilians besieged the city for two years and eventually forced its surrender, though Gibraltar remained in Moorish hands. The peninsula's defences had been greatly improved by Abu al-Hasan's construction of new walls, towers, magazines and a citadel, making its capture a much more difficult endeavour. Alfonso XI once again laid siege in 1349 following the death of Abu al-Hasan but was thwarted by the arrival of the Black Death in 1350, which decimated his army and claimed his own life.

Gibraltar remained in Moorish hands until 1462 but was disputed between rival Moorish factions. In 1374 the peninsula was handed over to the Moors of Granada, apparently as the price for their military support of the Moors of Fez in suppressing rebellions in Morocco. Gibraltar's garrison rebelled against the Granadans in 1410 but a Granadan army retook the place the following year after a brief siege. Gibraltar was subsequently used by the Granadans as the base for raids into Christian territory, prompting Enrique de Guzmán, second Count of Niebla, to lay siege in 1436. The attempt ended in disaster; the attack was repelled with heavy casualties and Enrique himself was drowned while trying to escape by sea. His decapitated body was hung on the walls of Gibraltar for the next twenty-two years.

The Moorish rule over Gibraltar came to an end in August 1462 when a small Castilian force under Enrique's son Juan Alonso, the first Duke of Medina Sidonia, launched a surprise attack while the town's senior commanders and townspeople were away paying homage to the new sultan of Granada. After a short Castilian assault which inflicted heavy losses on the defenders, the garrison surrendered.

Castilian and Spanish rule (1462-1704)

Shortly after Gibraltar had been retaken, King Henry IV of Castile declared it Crown property and reinstituted the special privileges which his predecessor had granted during the previous period of Christian rule. He visited Gibraltar in 1463 but was overthrown by the nobility and clergy four years later. His half-brother Alonso was declared king and rewarded Medina Sidonia for his support with the lordship of Gibraltar.

The existing governor, a loyalist of the deposed Henry IV, refused to surrender Gibraltar to Medina Sidonia. After a fifteen-month siege from April 1466 to July 1467, Medina Sidonia took control of the town. He died the following year but his son Enrique was confirmed as lord of Gibraltar by the reinstated Henry IV in 1469. His status was further enhanced by Isabella I of Castile in 1478 with the granting of the Marquisate of Gibraltar.

On 2 January 1492, after five years of war, the Moorish emirate in Spain came to an end with the Catholic Monarchs' capture of Granada. Gibraltar remained in Spanish hands but lost its Jewish population, expelled from Spain by order of the monarchs. It was used by Medina Sidonia as a base for the Spanish capture of Melilla in North Africa in 1497. Two years later the remaining Moors of Granada were ordered to convert to Christianity or be expelled; many were evacuated via Gibraltar.

Gibraltar became Crown property again in 1501 at the order of Isabella and received a new set of royal arms the following year to replace those of Medina Sidonia. In the Royal Warrant accompanying the arms, Isabella highlighted Gibraltar's importance as "the key between these our kingdoms in the Eastern and Western Seas "; the metaphor was represented on the royal arms by a golden key hanging from the front gate of a fortress. The warrant charged all future Spanish monarchs to "hold and retain the said City for themselves and in their own possession; and that no alienation of it, nor any part of it, nor its jurisdiction ... shall ever be made from the Crown of Castille."

By this time, Gibraltar had fallen into severe decline. The end of Muslim rule in Spain and the Christian capture of the southern ports considerably decreased the strategic value of Gibraltar. It had some minor economic value with wine and tunny-fishing industries but its usefulness as a fortress was now limited. It was effectively reduced to the status of an unremarkable stronghold on a rocky promontory and Marbella replaced it as the principal Spanish port in the region.

Its inhospitable terrain made it an unpopular place to live and it effectively became a penal camp for Christian renegades and Moorish prisoners of war. The second Duke of Medina Sidonia nonetheless sought the town's return and in September 1506, following Isabella's death, he laid siege in the expectation that the gates would quickly be opened to his forces. This did not happen and after a fruitless four-month blockade he gave up the attempt. The town received the title of "Most Loyal" from the Spanish crown in recognition of its faithfulness.

Barbary pirate raids

Despite continuing threats Gibraltar continued to be neglected and its fortifications fell into disrepair. Barbary pirates from North Africa took advantage of the weak defences in September 1540 by mounting a major raid on Gibraltar and seizing hundreds of citizens to hold as hostages or slaves. Many of the captives were subsequently released when a Spanish fleet intercepted the pirate ships as they were bringing ransomed hostages back to Gibraltar. The Spanish crown belatedly responded to Gibraltar's vulnerability by building the Charles V Wall and commissioning the Italian engineer Giovanni Battista Calvi to strengthen the fortifications.

The seas around Gibraltar continued to be a dangerous place for decades to come as Barbary pirate raids continued; although a small squadron of Spanish galleys was based at the port to counter pirate raids, it proved to be of limited effectiveness and many inhabitants were abducted and sold into slavery by the pirates. In response to their plight, the mendicant friars of Our Lady of Ransom established a monastery at Gibraltar in 1581, where they begged for money with which to buy back the abducted.

The problem worsened significantly after 1606, when Spain expelled its entire population of 600,000 Moriscos – Moors who had converted to Christianity. Many of the expellees were evacuated to North Africa via Gibraltar but ended up joining the pirate fleets, either as Christian slaves or reconverted Muslims, and raided as far afield as Cornwall.

The threat of the Barbary pirates was soon joined by that of Spain's enemies in northern Europe. On 5 May 1607 a Dutch fleet under Admiral Jacob van Heemskerk ambushed a Spanish fleet at anchor in the Bay of Gibraltar. The Dutch victory in the Battle of Gibraltar was total, losing no ships and very few men while the entire Spanish fleet was destroyed with the loss of 3,000 men.

Although the Spanish and Dutch temporarily declared a truce ten years later to deal with the pirate threat, in 1621 hostilities were resumed with a joint Dutch and Danish fleet arriving in the Strait to attack Spanish shipping. This time the Spanish succeeded in capturing and sinking a number of the attackers' ships, driving away the rest.

In 1620, an English military presence was briefly established at Gibraltar for the first time when the Spanish granted permission for an English fleet to use the port as a base for operations against the Barbary pirates. The Spanish suspected, correctly, that the real purpose of the fleet was aimed against Spain rather than the Barbary coast. However, James I successfully resisted Parliamentary pressure to declare war on Spain and the fleet returned to England.

A second English fleet arrived in 1625 with instructions to "take or spoil a town" on the Spanish coast. Gibraltar was proposed as a target on the basis that it was small, could easily be garrisoned, supplied and defended, and was in a highly strategic location. In the event, the English fleet attacked Cadiz, but the raid turned into a fiasco. The landing force gorged itself on wine stores in the town before being evacuated without achieving anything useful.

The presence of Spain's enemies in the Straits prompted the Spanish king Philip IV to order a strengthening of Gibraltar's defences with the construction of a new mole and gun platforms, though the latter's usefulness was limited due to a lack of gunners. The town remained an insanitary, crowded place, which probably contributed to the outbreak in 1649 of an epidemic disease – reportedly plague but possibly typhoid – which killed a quarter of the population. English fleets returned to Gibraltar in 1651-52 and again in 1654-55 as temporary allies of the Spanish against French and Dutch shipping in the Straits.

After Spain declared war on England in February 1656, a fleet of 49 English warships manned by 10,000 sailors and soldiers put to sea in the Straits and reconnoitred Gibraltar at the suggestion of Oliver Cromwell, who expressed interest in its capture: "if possessed and made tenable by us, would it not be both an advantage to our trade, and an annoyance to the Spaniards, and enable us ... ease our own charge?" However, the lack of a viable landing force precluded an English capture of Gibraltar at this time.

The War of the Spanish Succession (1701–1714)

Main article: War of the Spanish Succession

In November 1700, Charles II of Spain died childless. The dispute over who should succeed him – the French Prince Philip of Anjou, grandson of Louis XIV of France or the Habsburg Archduke Charles of Austria – soon plunged Europe into a major war. Louis XIV supported Philip. England, the Netherlands, Austria, Portugal, Savoy and some of the German states supported Charles, fearing that Philip's accession would result in France dominating Europe and the Americas. In May 1702, Queen Anne formally declared war on France, opening the War of the Spanish Succession.

By this time Philip had been proclaimed as Philip V of Spain and had allied his kingdom with France. Spain thus became a target for the Anglo-Dutch-Austrian alliance. The confederates' campaign was pursued both by land and by sea. The main land offensive was pursued in the Low Countries by the Duke of Marlborough, while naval forces under the command of Admiral Sir George Rooke harassed French and Spanish shipping in the Atlantic. In 1703, Marlborough devised a plan under which his forces would launch a surprise attack against the French and their Bavarian allies in the Danube basin while Rooke carried out a diversionary naval offensive in the Mediterranean. Rooke was instructed to attack French or Spanish coastal towns, though the choice of target was left to his discretion.

When Rooke arrived in the region several targets were considered. An attempt to incite the inhabitants of Barcelona to revolt against Philip V failed, and a plan to assault the French naval base at Toulon was abandoned. Casting around for an alternative target, Rooke decided to attack Gibraltar for three principal reasons: it was poorly garrisoned, it would be of major strategic value to the war effort and its capture would encourage the inhabitants of southern Spain to reject Philip.

The attack was launched on 1 August 1704 as a combined operation between the naval force under Rooke's command and a force of Dutch and English marines under the command of Prince George of Hesse-Darmstadt and Captain Whittaker of HMS Dorsetshire. After a heavy naval bombardment on 2 August, the marines launched a pincer attack on the town, advancing south from the isthmus and north from Europa Point. Gibraltar's defenders were well stocked with food and ammunition but were heavily outnumbered and outgunned. The Spanish position was clearly untenable and on the morning of 4 August, the governor, Diego de Salinas, agreed to surrender.

The terms of surrender made it clear that Gibraltar had been taken in the name of Charles III of Spain, described in the terms as "legitimate Lord and King". The inhabitants and garrison of Gibraltar were promised freedom of religion and the maintenance of existing rights if they wished to stay, on condition that they swore an oath of loyalty to Charles. As had happened two years previously in an Anglo-Dutch raid on Cadiz, the discipline of the landing forces soon broke down and there were numerous incidents of rape, all Catholic churches but one (the Parish Church of St. Mary the Crowned, now the Cathedral) were desecrated or pressed into service as military storehouses, and religious symbols, such the statue of Our Lady of Europe, were damaged and destroyed. The angry inhabitants took reprisals, killing Englishmen and Dutchmen and throwing the bodies into wells and cesspits.

When the garrison marched out on 7 August almost all of the inhabitants, some 4,000 people in total, joined them. They had reason to believe that their exile would not last long; fortresses changed hands frequently at the time. Many thus resettled nearby in the ruins of Algeciras or around the old hermitage at San Roque at the head of the bay. They took with them the records of the city council including Gibraltar's banner and royal warrant. The newly founded town of San Roque thus became, as Philip V put it in 1706, "My City of Gibraltar resident in its Campo". A small population of neutral Genoese numbering some seventy people stayed behind in Gibraltar.

The confederates' control of Gibraltar was challenged on 24 August when a French fleet entered the Straits. In the subsequent Battle of Vélez-Málaga, both sides sustained heavy crew casualties though no loss of ships. The French withdrew to Toulon without attempting to assault Gibraltar. In early September a Franco-Spanish army arrived outside Gibraltar and prepared for a siege which they commenced on 9 October. Some seven thousand French and Spanish soldiers, aided by refugees from Gibraltar, were pitted against a force of around 2,500 defenders consisting of English and Dutch marines and Spaniards loyal to Charles.

The defenders were aided from late October by a naval squadron under Admiral Sir John Leake. A further 2,200 English and Dutch reinforcements arrived by sea with fresh supplies of food and ammunition in December 1704. With morale falling in the Franco-Spanish camp amid desertions and sickness, Louis XIV despatched Marshal de Tessé to take command in February 1705. A Franco-Spanish assault was beaten back with heavy casualties and on 31 March, de Tessé gave up the siege, complaining of the "want of method and planning."

Gibraltar was now nominally a possession of Charles of Austria but in practice it was increasingly ruled as a British possession. The British commandant, Major General John Shrimpton, was appointed by Charles as Gibraltar's governor in 1705 on the advice of Queen Anne. The queen subsequently declared Gibraltar a free port at the insistence of the Sultan of Morocco, though she had no formal authority to do so. Shrimpton was replaced in 1707 by Colonel Roger Elliot, who was replaced in turn by Brigadier Thomas Stanwix in 1711; this time the appointments were made directly by London with no claim of authority from Charles. Stanwix was ordered to get rid of all foreign troops from Gibraltar to secure its status as an exclusively British possession but failed to evict the Dutch, apparently not considering them "foreign."

The War of the Spanish Succession was finally settled in 1713 by a series of treaties and agreements. Under the Treaty of Utrecht, which was signed on 11 April 1713 and brought together a number of sub-treaties and agreements, Philip V was accepted by Britain and Austria as king of Spain in exchange for guarantees that the crowns of France and Spain would not be unified. Various territorial exchanges were agreed, among them (Article X) the cession of the town, fortifications and port of Gibraltar (but not its hinterland) to Britain "for ever, without any exception or impediment whatsoever." The treaty also stipulated that if Britain was ever to dispose of Gibraltar it would first have to offer the territory to Spain.

British rule (1713-present)

Consolidation and sieges

Despite its later importance to Britain, Gibraltar was initially seen by the British Government as more of a bargaining counter than a strategic asset. Its defences continued to be neglected, its garrisoning was an unwelcome expense and Spanish pressure threatened Britain's vital overseas trade. On seven separate occasions between 1713 and 1728 the British Government proposed to exchange Gibraltar for concessions from Spain, but on each occasion the proposals were vetoed by the British Parliament following public protests.

Spain's loss of Gibraltar and other Spanish territories in the Mediterranean was resented by the Spanish public and monarchy alike. In 1717 Spanish forces retook Sardinia and in 1718 Sicily, both of which had been ceded to Austria under the Treaty of Utrecht. The effective Spanish repudiation of the treaty prompted the British initially to propose handing back Gibraltar in exchange for a peace agreement and, when that failed, to declare war on Spain. The Spanish gains were quickly reversed, a Spanish attempt to invade Scotland in 1719 failed and peace was eventually restored in 1721.

In January 1727, Spain declared the nullification of the Treaty of Utrecht's provisions relating to Gibraltar on the grounds that Britain had violated its terms by extending Gibraltar's fortifications beyond the permitted limits, allowing Jews and Moors to remain, failing to protect Catholics and harming Spain's revenues by allowing smuggling. Spanish forces began a siege and bombardment of Gibraltar the following month, causing severe damage through intensive cannon fire. The defenders were nonetheless able to withstand the threat and were reinforced and resupplied by a British naval force. Bad weather and supply problems caused the Spanish to call off the siege at the end of June.

Britain's hold on Gibraltar was reconfirmed in 1729 by the Treaty of Seville, which satisfied neither side; the Spanish had wanted Gibraltar returned, while the British disliked the continuation of the restrictions imposed by the Treaty of Utrecht. Spain responded the following year by constructing a line of fortifications across the upper end of the peninsula, cutting off Gibraltar from its hinterland. The fortifications, known to the British as the Spanish Lines, and to Spain as La Línea de Contravalación (the Lines of Contravallation), were later to give their name to the modern town of La Línea de la Concepción. Gibraltar was effectively blockaded by land but was able to rely on trade with Morocco for food and other supplies.

Gibraltar's civilian population increased steadily through the century to form a disparate mixture of Britons, Genoese, Jews, Spaniards and Portuguese. By 1754 there were 1,733 civilians in addition to 3,000 garrison soldiers and their 1,426 family members, bringing the total population to 6,159. The civilian population increased to 3,201 by 1777, including 519 Britons, 1,819 Roman Catholics (meaning Spanish, Portuguese, Genoese etc.) and 863 Jews. Each group had its own distinctive niche in the fortress. The Spanish historian López de Alaya, writing in 1782, characterised their roles thus:

The richest mercantile houses are English ... The Jews, for the most part, are shop keepers and brokers ... They have a synagogue and openly practice the ceremonies of their religion, notwithstanding the terms of the Treaty of Utrecht ... The Genoese are traders, but the greater part of them are fishermen, traders and gardeners.

The fortifications of Gibraltar were modernised and upgraded in the 1770s with the construction of new batteries, bastions and curtain walls. The driving force behind this programme was the highly experienced Colonel (later Major General) William Green, who was to play a key role a few years later as chief engineer of Gibraltar. He was joined in 1776 by Lieutenant General George Augustus Elliott, a veteran of earlier wars against France and Spain who took over the governorship of Gibraltar at a key moment.

Britain's successes in the Seven Years' War had left it with expensive commitments in the Americas that had to be paid for, as well as catalysing the formation of an anti-British coalition in Europe. The British Government's attempt to levy new taxes on the Thirteen Colonies of British America led to the outbreak of the American War of Independence in 1776. Seeing an opportunity to reverse their own territorial losses, France and Spain declared war on Britain and allied with the American revolutionaries.

In June 1779, Spain began the fourteenth and longest siege of Gibraltar, known as the Great Siege. The Spanish had learned the lessons of the failure of previous sieges and this time assaulted Gibraltar from both land and sea as well as cutting off its supply lines to Morocco. The intense bombardments from land batteries, gunboats and specially constructed "floating batteries" reduced much of the town of Gibraltar to ruins. The lack of food led to starvation and outbreaks of scurvy and other diseases. The garrison nonetheless held on, repelling several major Spanish attacks and carrying out sorties against the besieging forces. It was reinforced and restocked by several British supply convoys that successfully broke through the Spanish blockade of the Straits. The siege dragged on for over three and a half years before peace was finally declared with Britain ceding West Florida, East Florida and Minorca to Spain but keeping Gibraltar.

Gibraltar as a colony

Following the Great Siege, the civilian population of Gibraltar – which had fallen to under a thousand – expanded rapidly as the territory became both a place of economic opportunity and a refuge from the Napoleonic Wars. Britain's loss of its North American colonies in 1776 led to much of her trade being redirected to new markets in India and the East Indies. The favoured route to the east was via Egypt, even before the Suez Canal had been built, and Gibraltar was the first British port reached by ships heading there on that trade route. The new maritime traffic gave Gibraltar a greatly increased role as a trading port. At the same time, it was a haven in the western Mediterranean from the disruption of the Napoleonic Wars. Many of the new immigrants were Genoese people who had fled Napoleon's annexation of the old Republic of Genoa. By 1813 nearly a third of the population consisted of Genoese and Italians. Portuguese made up another 20 per cent, Spaniards 16.5 per cent, Jews 15.5 per cent, British 13 per cent and Minorcans 4 per cent. The young Benjamin Disraeli described the inhabitants of Gibraltar as a mixture of "Moors with costumes as radiant as a rainbow or Eastern melodrama, Jews with gaberdines and skull-caps, Genoese, Highlanders and Spanish." However, the fortress was an unhealthy place to live due to its poor sanitation and living conditions. It was repeatedly ravaged by epidemics of yellow fever and cholera, which killed thousands of the inhabitants and members of the garrison. An epidemic in the second half of 1804 killed over a third of the entire population, civilian and military.

During the wars against Napoleonic France, Gibraltar served first as a Royal Navy base from which blockades of the ports of Cadiz, Cartagena and Toulon were mounted, then latterly as a gateway for British forces and supplies in the Peninsular War between 1807–14. In July 1801 a French and Spanish naval force fought the First and Second Battle of Algeciras off Gibraltar, which ended in disaster for the Spanish when two of their largest warships each mistook the other for the enemy, engaged each other, collided, caught fire and exploded, killing nearly 2,000 Spanish sailors. Four years later Gibraltar served as a base for Lord Nelson in his efforts to bring the French Admiral Pierre-Charles Villeneuve to battle, which culminated in the Battle of Trafalgar in which Nelson was killed and Villeneuve captured. The British fleet returned to Gibraltar for repairs before HMS Victory returned to England with Nelson's body aboard.

In the years after Trafalgar, Gibraltar became a major supply base for supporting the Spanish uprising against Napoleon. The French invasion of Spain in 1808 prompted Gibraltar's British garrison to cross the border to destroy the ring of Spanish fortresses around the Bay of Gibraltar, as well as the old Spanish fortified lines on the isthmus north of Gibraltar, to deny the French the ability to besiege the fortress or control the bay from shore batteries. French forces reached as far as San Roque, just north of Gibraltar, but did not attempt to target Gibraltar itself as they believed that it was impregnable. The French unsuccessfully besieged Tarifa, further down the coast, in 1811–12 but gave up after a month. Thereafter, Gibraltar faced no further military threat for a century.

After peace returned, Gibraltar underwent major changes during the reformist governorship of General Sir George Don, who took up his position in 1814. The damage caused by the Great Siege had long since been repaired but Gibraltar was still essentially a medieval town in its layout and narrow streets. A lack of proper drainage had been a major contributing factor in the epidemics that had frequently ravaged the fortress. Don implemented improved sanitation and drainage as well as introducing street lighting, rebuilding St Bernard's Hospital to serve the civilian population and initiating the construction of the Cathedral of the Holy Trinity to serve Gibraltar's Protestant civilians. For the first time, civilians now began to have a say in the running of Gibraltar. An Exchange and Commercial Library was founded in 1817, with the Exchange Committee initially focused on furthering the interests of merchants based in the fortress. The Committee evolved into a local civilian voice in government, although it had no real powers. A City Council was established in 1821, and in 1830 Gibraltar became a Crown colony. The Gibraltar Police Force was established in the same year, modelled on London's pioneering Metropolitan Police Service. A Supreme Court was also set up in the same year to try civil, criminal and mixed cases.

The economic importance of Gibraltar changed following the invention of steamships; the first one to reach Gibraltar's harbour arrived there in 1823. The advent of steamships caused a major shift in trade patterns in the Mediterranean. Transshipment, which had previously been Gibraltar's principal economic mainstay, was largely replaced by the much less lucrative work of servicing visiting steamships through coaling, victualling and ferrying of goods. Although Gibraltar became a key coaling station where British steamships refuelled on the way to Alexandria or Cape Horn, the economic changes resulted in a prolonged depression that lasted until near the end of the century. The demand for labour for coaling was such that Gibraltar instituted the practice, which still continues today, of relying on large numbers of imported Spanish workers. A shanty town sprang up on the site of the old Spanish fortifications just across the border, which became the workers' town of La Línea de la Concepción. The poor economy meant that Gibraltar's population barely changed between 1830 and 1880, but it was still relatively more prosperous than the severely impoverished south of Spain. As a consequence, La Línea's population doubled over the same period and then doubled again in the following 20 years.

Relations with Spain during the 19th century were generally amicable but a major bone of contention was the problem of smuggling. The problem arose as a result of the Spanish government deciding to impose tariffs on foreign manufactured goods in a bid to protect Spain's own fledgling industrial enterprises. Tobacco was also heavily taxed, providing one of the government's principal sources of revenue. The inevitable result was that Gibraltar, where cheap tobacco and goods were readily available, became a centre of intensive smuggling activity. The depressed state of the economy meant that smuggling became a mainstay of Gibraltar's trade. General Sir Robert Gardiner, who served as Governor between 1848–55, described the daily scene in a letter to British Prime Minister Lord Palmerston:

From the first early opening of the gates there is to be seen a stream of Spanish men, women and children, horses and a few caleches, passing into the town where they remain moving about from shop to shop until about noon. The human beings enter the Garrison in their natural sizes, but quit it swathed and swelled out with our cotton manufactures, and padded with tobacco, while the carriages and beasts, which come light and springy into the place, quit it scarcely able to drag or bear their burdens. The Spanish authorities bear part in this traffic, by receiving a bribe from every individual passing the Lines, their persons and their purposes being thoroughly known to them. Some of these people take hardware goods, as well as cotton and tobacco, into Spain.

The problem was eventually reduced by imposing duties on imported goods, which made them much less attractive to smugglers and raised funds to make much-needed improvements to sanitation. Despite the improvements made earlier in the century, living conditions in Gibraltar were still dire. A Colonel Sayer, who was garrisoned at Gibraltar in the 1860s, described the town as "composed of small and crowded dwellings, ill ventilated, badly drained and crammed with human beings. Upwards of 15,000 persons are confined within a space covering a square mile." Although there were sewers, a lack of water meant that they were virtually useless in summer and the poorer inhabitants were sometimes unable to afford enough water even to wash themselves. One doctor commented that "the open street is much more desirable than many of the lodgings of the lower orders of Gibraltar." The establishment of a Board of Sanitary Commissioners in 1865 and work on new drainage, sewerage and water supply systems prevented further major epidemics from that point on. A system of underground reservoirs capable of containing 5 million gallons (22.7 million litres) of water was constructed within the Rock of Gibraltar. Other municipal services arrived as well – a gas works in 1857, a telegraph link by 1870, and electricity by 1897. Gibraltar also developed a high-quality school system, with as many as 42 schools by 1860.

By the end of the 19th century, a distinct "Gibraltarian" identity had evolved. It was only in the 1830s that Gibraltar-born residents began to outnumber foreign-born, but by 1891 nearly 75% of the population of 19,011 people was Gibraltar-born. The emergence of the Gibraltarians as a distinct group owed much to the pressure on housing in the territory and the need to control the numbers of the civilian population, as Gibraltar was still first and foremost a military fortress. Two Orders in Council of 1873 and 1885 stipulated that no foreigners could claim a right of residence in Gibraltar and that only Gibraltar-born inhabitants were entitled to reside there; everyone else needed permits, unless they were employees of the British Crown. This was, in effect, the first official recognition of a Gibraltarian identity. In addition to the 14,244 Gibraltarians, there were also 711 British people, 695 Maltese and 960 from other British dominions. There were 1,869 Spaniards (of whom 1,341 were female - generally wives and prostitutes) with smaller numbers of Portuguese, Italians, French and Moroccans.

Gibraltar at war and peace

By the end of the 19th century and beginning of the 20th, Gibraltar's future as a British colony was in serious doubt. Its economic value was diminishing, as a new generation of steamships with a much longer range no longer needed to stop there to refuel en route to more distant ports. Its military value was also increasingly in question due to advances in military technology. New long-range guns firing high-explosive shells could easily reach Gibraltar from across the bay or in the Spanish hinterland, while the development of torpedos meant that ships at anchor in the bay were also vulnerable. The garrison could hold out for a long time, but if the Spanish coast was held by an enemy, Gibraltar could not be resupplied in the fashion that had saved it in the Great Siege 120 years earlier.

A Spanish proposal to swap Gibraltar for Ceuta on the other side of the Strait was considered but was eventually rejected. It was ultimately decided that Gibraltar's strategic position as a naval base outweighed its potential vulnerability from the landward side. From 1889, the Royal Navy was greatly expanded and both Gibraltar and Malta were equipped with new, torpedo-proof harbours and expanded, modernised dockyards. The works at Gibraltar were carried out by some 2,200 men at the huge cost of £5 million (£485,968,723 today). Under the reforming leadership of First Sea Lord Admiral John "Jacky" Fisher, Gibraltar became the base for the Atlantic Fleet.

The value of the naval base was soon apparent when the First World War broke out in August 1914. Only a few minutes after the declaration of war went into effect at midnight on 3/4 August, a German liner was captured by a torpedo boat from Gibraltar, followed by three more enemy ships the following day. Although Gibraltar was well away from the main battlefields of the war – Spain remained neutral and the Mediterranean was not contested as it was in the Second World War – it played an important role in the Allied fight against the German U-boat campaign. The naval base was heavily used by Allied warships for resupplying and repairs. The Bay of Gibraltar was also used as a forming-up point for Allied convoys, while German U-boats stalked the Strait looking for targets. On two occasions, Gibraltar's guns unsuccessfully fired upon two U-boats travelling through the Strait. Anti-submarine warfare was in its infancy and it proved impossible to prevent U-boats operating through the Strait. Only two days before the end of the war, on 9 November 1918, SM UB-50 torpedoed and sank the British battleship HMS Britannia off Cape Trafalgar to the west of Gibraltar.

The restoration of peace inevitably meant a reduction in military expenditure, but this was more than offset by a large increase in liner and cruise ship traffic to Gibraltar. British liners travelling to and from India and South Africa customarily stopped there, as did French, Italian and Greek liners travelling to and from America. Oil bunkering became a major industry alongside coaling. An airfield was established in 1933 on the isthmus linking Gibraltar to Spain. Civil society was reformed as well; in 1921 an Executive Council and an elected City Council were established to advise the governor, in the first step towards self-government of the territory.

The outbreak of the Spanish Civil War in July 1936 presented Gibraltar with major security concerns, as it was virtually on the front lines of the conflict. The ultimately successful rebellion led by General Francisco Franco broke out across the Strait in Morocco, and the Spanish Republican government sought on several occasions to regain control of the Nationalist-controlled area around Algeciras. Around 4,000 Spanish refugees fled to Gibraltar. With Europe sliding towards a general war, the British Government decided to strengthen Gibraltar's defences and upgrade the naval base to accommodate the latest generation of battleships and aircraft carriers. A Gibraltar Defence Force (now the Royal Gibraltar Regiment) was established in March 1939 to assist with home defence.

Second World War

Main article: Military history of Gibraltar during World War II

The outbreak of the Second World War in September 1939 did not initially cause much disruption in Gibraltar, as Spain and Italy were neutral at the time. The situation changed drastically after April 1940 when Germany invaded France, with Italy joining the invasion in June 1940. The British Government feared that Spain would also enter the war and it was decided to evacuate the entire civilian population of Gibraltar in May 1940, mostly to the United Kingdom but also to Madeira and Jamaica, with some making their own way to Tangier and Spain. An intensive programme of tunnelling and refortification was undertaken; over 30 miles (48 km) of tunnels were dug in the Rock and anti-aircraft batteries were installed in numerous locations in the territory. A new and powerful fleet called Force H was established at Gibraltar to control the entrance to the Mediterranean and support Allied forces in North Africa, the Mediterranean and the Battle of the Atlantic. The airfield, which was now designated RAF North Front, was also extended using spoil from the tunnelling works so that it could accommodate bomber aircraft being ferried to North Africa. The garrison was greatly expanded, reaching a peak of 17,000 in 1943 with another 20,000 sailors and airmen accommodated in Gibraltar at the same time.

Gibraltar was directly attacked, both overtly and covertly, on several occasions during the war. Gibraltar was bombed by Vichy French aircraft in 1940 and subsequently experienced sporadic raids from Italian and German long-range aircraft, though the damage caused was not significant. German and Italian spies kept a constant watch on Gibraltar and sought to carry out sabotage operations, sometimes successfully. The Italians repeatedly carried out raids on Gibraltar's harbour using human torpedos and divers operating from the Spanish shore, damaging a number of merchant ships and sinking one. Three Spaniards being run as spies and saboteurs by the German Abwehr were caught in Gibraltar in 1942–43 and hanged. The position of the Spanish government was ambiguous; although Spain allowed the Axis powers to operate covertly against Gibraltar, Franco decided not to join Hitler's planned Operation Felix to seize the territory. Hitler eventually abandoned Felix to pursue other priorities such as the invasion of Yugoslavia and the Soviet Union.

The immediate threat to Gibraltar lessened after the collapse of Italy in September 1943. The Allied forces garrisoned there continued to play a central role in operations in the Mediterranean, supporting the campaigns in Tunisia, Sicily and mainland Italy. Gibraltar served as a waypoint for a huge amount of air and naval traffic through to the end of the war.

Post-war Gibraltar

Although Gibraltar's civilian inhabitants had started to return as early as April 1944, it was not until as late as February 1951 that all the evacuees were able to return home. The immediate problem was a lack of shipping, as all available vessels were needed to bring troops home, but the longer-term problem was a lack of civilian housing. The garrison was relocated to the southern end of the peninsula to free up space and military accommodation was temporarily reused to house the returning civilians. A programme to build housing projects was implemented, though progress was slow due to shortages of building materials. By 1969, over 2,500 flats had either been built or were under construction.

In the war's aftermath, Gibraltar made decisive steps towards civilian self-rule. The Association for the Advancement of Civil Rights (AACR), led by Gibraltarian lawyer Joshua Hassan, won all of the seats in the first post-war City Council elections in 1945. Women were given the right to vote in 1947, and in 1950 a Legislative Council was established. A two-party system had emerged by 1955 with the creation of the Commonwealth Party as a rival to the AACR. That same year Hassan became the first Mayor of Gibraltar. The Governor still retained overall authority and could overrule the Legislative Council. This inevitably caused tension and controversy if the Governor and Legislative Council disagreed, but in 1964 British Government agreed to confine the powers of the Governor to matters of defence, security and foreign relations. A new constitution was agreed in 1968 and promulgated in 1969, merging the City Council and Legislative Council into a single House of Assembly (known as the Gibraltar Parliament since 2006) with 15 elected members, two non-elected officials and a speaker. The old title of "Colony of Gibraltar" was dropped and the territory was renamed as the City of Gibraltar.

Gibraltar's post-war relationship with Spain was marred by an intensification of the long-running dispute over the territory's sovereignty. Although Spain had not attempted to use military force to regain Gibraltar since 1783, the question of sovereignty had never really gone away. Disputes over smuggling and the sea frontier between Gibraltar and Spain had repeatedly caused diplomatic tensions during the 19th century. The neutral zone between Spain and Gibraltar had also been a cause of disputes during the 19th and 20th centuries. This originally had been an undemarcated strip of sand on the isthmus between the British and Spanish lines of fortifications, about 1 kilometre (0.62 mi) wide – the distance of a cannon shot in 1704. Over the years, however, Britain took control of most of the neutral zone, much of which is now occupied by Gibraltar's airport. This expansion provoked repeated protests from Spain.

Spain made a fresh attempt to regain sovereignty over Gibraltar following the end of the Second World War. Franco's government calculated that a Britain that had been crippled economically by six years of total war would be willing to give up an expensive colony that no longer had a great deal of military value. Additionally, the decolonization agenda of the United Nations gave diplomatic backing to Spain's objectives. However, this turned out to be a fundamental misjudgement. The British government followed a policy of allowing its colonies to become self-governing entities before giving them the option of independence. Almost all took it, choosing to become independent republics. That option was not available to Gibraltar due to the terms of the Treaty of Utrecht, which required that if Britain ever relinquished control it was to be handed back to Spain. The Gibraltarians strongly opposed this and organised a referendum in September 1967 in which 12,138 voters opted to remain with Britain and only 44 supported union with Spain. Spain dismissed the outcome of the referendum, calling the city's inhabitants "pseudo-Gibraltarians" and stating that the "real" Gibraltarians were the descendants of the Spanish inhabitants who had resettled elsewhere in the region over 250 years earlier.

The dispute initially took the form of symbolic protests and a campaign by Spanish diplomats and the state-controlled media. From 1954, Spain imposed increasingly stringent restrictions on trade and the movements of vehicles and people across the border with Gibraltar. Further restrictions were imposed in 1964 and in 1966 the frontier was closed to vehicles. The following year, Spain closed its airspace to aircraft taking off or landing at Gibraltar International Airport. In 1969, after the passing of the Gibraltar Constitution Order, to which Spain strongly objected, the frontier was closed completely and Gibraltar's communications links with the outside world were cut. It was not until 5 February 1985 that the border was fully reopened in return for British support for Spain's bid to join the European Economic Community.

Modern Gibraltar

After the border reopened, the British government reduced the military presence in Gibraltar by closing the naval dockyard. The RAF presence was also downgraded; although the airport officially remains an RAF base, military aircraft are no longer permanently stationed there. The British garrison, which had been present since 1704, was withdrawn in 1990 following defence cutbacks at the end of the Cold War. A number of military units continue to be stationed in Gibraltar under the auspices of British Forces Gibraltar; the garrison was replaced with locally-recruited units of the Royal Gibraltar Regiment, while a Royal Navy presence is continued through the Gibraltar Squadron, responsible for overseeing the security of Gibraltar's territorial waters. In March 1988 a British military operation against members of the Provisional IRA (PIRA) planning a car bomb attack in Gibraltar ended in controversy when the Special Air Service shot and killed all three PIRA members.

The military cutbacks inevitably had major implications for Gibraltar's economy, which had up to that point depended largely on defence expenditure. It prompted the territory's government to carry out a major shift in its economic orientation and place a much greater emphasis on encouraging tourism and establishing self-sufficiency. Tourism in Gibraltar was encouraged through refurbishing and pedestrianising key areas of the city, building a new passenger terminal to welcome cruise ship visitors and opening new marinas and leisure facilities. By 2011, Gibraltar was attracting up to 12 million visits a year, giving it one of the highest tourist-to-resident ratios in the world.

The government also encouraged the development of new industries such as financial services, duty-free shopping, casinos and Internet gambling providers. Branches of major British chains such as Marks & Spencer were opened in Gibraltar to encourage visits from British expatriates on the nearby Costa del Sol. To facilitate the territory's economic expansion, a major programme of land reclamation was carried out; land reclaimed from the sea now accounts for a tenth of Gibraltar's land area. These initiatives proved enormously successful. By 2007 Peter Caruana, the Chief Minister, was able to boast that Gibraltar's economic success had made it "one of the most affluent communities in the entire world."

Key locations in modern Gibraltar-

Grand Casemates Square, renovated and pedestrianised in the late 1990s.

Grand Casemates Square, renovated and pedestrianised in the late 1990s.

-

Ocean Village Marina, a luxury marina resort with premier berths for yachts.

Ocean Village Marina, a luxury marina resort with premier berths for yachts.

-

The new terminal of Gibraltar International Airport, opened in 2012, with the Rock of Gibraltar behind

The new terminal of Gibraltar International Airport, opened in 2012, with the Rock of Gibraltar behind

Gibraltar's relationship with Spain continued to be a sensitive subject. By 2002, Britain and Spain had reached an agreement on sharing sovereignty over Gibraltar. However, it was opposed by the government of Gibraltar, which put it to a referendum in November 2002. The agreement was rejected by 17,000 votes to 187 – a majority of 98.97%. Although both governments dismissed the outcome as having no legal weight, the outcome of the referendum caused the talks to stall and the British government accepted that it would be unrealistic to try to reach an agreement without the support of the people of Gibraltar.

The tercentenary of Britain's capture of Gibraltar was celebrated in the territory in August 2004 but attracted criticism from some in Spain. In September 2006, tripartite talks between Spain, Gibraltar and the UK resulted in a deal (known as the Cordoba Agreement) to make it easier to cross the border and to improve transport and communications links between Spain and Gibraltar. Among the changes was an agreement to lift restrictions on Gibraltar's airport to make enable airlines operating from Spain to land there and to facilitate use of the airport by Spanish residents. It did not address the vexed issue of sovereignty, but this time the government of Gibraltar supported it. A new Constitution Order was promulgated in the same year, which was approved by a majority of 60.24% in a referendum held in November 2006.

See also

General:

Notes

- ^ Rincon, Paul (13 September 2006). "Neanderthals' 'last rock refuge'". BBC News.

- Dunsworth, Holly M. (2007). Human Origins 101. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-313-33673-7.

- Bruner, E.; Manzi, G. (2006). "Saccopastore 1: the earliest Neanderthal? A new look at an old cranium". In Harvati, Katerina; Harrison, Terry (eds.). Neanderthals revisited: new approaches and perspectives. Vertebrate paleobiology and paleoanthropology, vol. 2. Springer. p. 31. ISBN 978-1-4020-5120-3.

- "The Gibraltar Neanderthals". Retrieved 16 November 2009.

- ^ Stringer, Chris (2000). "Digging the Rock". In Whybrow, Peter J. (ed.). Travels with the Fossil Hunters. Cambridge University Press. p. 48. ISBN 978-0-521-66301-4.

- Padró i Parcerisa, p. 128

- Jackson, p. 20

- ^ Hills, p. 14

- ^ Hills, p. 13

- Hills, p. 15

- Hill, p. 19

- ^ Jackson, p. 22

- Shields, p. ix

- Collins, p. 106

- Truver, p. 161

- Hills, p. 18

- Hills, p. 30

- Jackson, pp. 21-25

- Jackson, p. 28

- Jackson, pp. 34-35

- Jackson, p. 38

- Jackson, pp. 39-40

- Hills, p. 49-50

- Jackson, p. 41

- Jackson, p. 42

- Jackson, p. 44

- Jackson, p. 46

- Jackson, p. 47

- Jackson, p. 49

- Jackson, p. 51

- Jackson, p. 52

- Jackson, pp. 52-53

- Jackson, p. 55

- Jackson, p. 56

- Jackson, pp. 57-58

- Jackson, p. 63

- ^ Jackson, p. 65

- Jackson, p. 67

- ^ Jackson, p. 70

- ^ Jackson, p. 72

- Finlayson, p. 17

- Jackson, p. 73

- Jackson, p. 75

- ^ Jackson, p. 78

- Jackson, p. 80

- ^ Jackson, p. 81

- Jackson, p. 82

- Jackson, p. 84

- ^ Jackson, p. 86

- Jackson, pp. 89-91

- Jackson, p. 91

- Jackson, p. 92

- Jackson, p. 93

- Jackson, p. 94

- Jackson, p. 96

- Jackson, p. 97

- Jackson, p. 98

- Jackson, p. 99

- Jackson, p. 101

- Jackson, p. 102

- Jackson, p. 106

- Jackson, p. 109

- Jackson, p. 110

- Jackson, p. 111

- Jackson, p. 113

- Jackson, p. 114

- Jackson, p. 113, 333-34

- Abulafia (2011), p. 47.

- ^ Jackson, p. 118

- ^ Jackson, p. 119

- ^ Jackson, p. 120

- ^ Jackson, p. 115

- Jackson, p. 123

- Jackson, p. 124

- Jackson, p. 128

- Jackson, p. 132

- Jackson, p. 139

- Jackson, p. 140

- Jackson, p. 143

- Jackson, p. 153

- Ayala, p. 171-75

- Jackson, pp. 147-49

- ^ Jackson, p. 150

- Jackson, p. 152

- Jackson, p. 154

- Jackson, p. 166-67

- Jackson, p. 177-79

- ^ Jackson, p. 181

- Alexander, pp. 159–160

- Jackson, p. 196

- Jackson, p. 192

- Jackson, p. 199

- Jackson, p. 200

- Jackson, p. 209

- Jackson, p. 213

- Jackson, p. 370

- Alexander, pp. 161–162

- Alexander, p. 162

- Alexander, p. 163

- Jackson, p. 229

- Alexander, p. 166

- ^ Jackson, p. 242

- Hills, p. 381

- Alexander, p. 164

- Alexander, p. 172

- Hills, p. 374

- Hills, p. 380

- Jackson, p. 243

- ^ Jackson, p. 244 Cite error: The named reference "Jackson-244" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- Alexander, p. 187

- Jackson, p. 245

- Jackson, p. 247

- Jackson, p. 248

- Jackson, p. 249

- Jackson, p. 255

- Bradford, p. 169

- Jackson, p. 255

- Jackson, p. 257

- Alexander, p. 189

- Hills, p. 398

- Jackson, p. 264

- Jackson, p. 265

- Jackson, p. 268

- Jackson, p. 270

- ^ Jackson, p. 271

- Jackson, p. 276

- Jackson, p. 286

- ^ Jackson, p. 293

- Jackson, p. 281

- Jackson, pp. 286–87

- Jackson, pp. 282–83

- Jackson, p. 296

- Alexander, p. 235

- Alexander, p. 236

- ^ Alexander, p. 237

- ^ Alexander, p. 241

- Hills, p. 375

- Jackson, p. 250

- Jackson, p. 294

- Jackson, p. 295

- Jackson, p. 306

- Jackson, p. 300

- Jackson, p. 308

- Jackson, p. 316

- Jackson, p. 327

- ^ Alexander, p. 246

- ^ Alexander, p. 247

- Archer, p. 2

- Gold, pp. 177, 192

- "Tourist Survey Report 2011" (PDF). Government of Gibraltar. Retrieved 29 November 2012.

- Aldrich & Connell, p. 83

- "Q&A: Gibraltar's referendum". BBC News. 8 November 2002.

- Horsley, William (9 June 2003). "UK upsets Spain's Gibraltar plans". BBC News.

- "Spain 'obsessed' with Gibraltar". BBC News. 2 August 2004.

- Alexander, p. 248

- Alexander, p. 249

References

- Abulafia, David (2011). The Great Sea: A Human History of the Mediterranean. London: Allen Lane. ISBN 978-0-7139-9934-1.

- Alexander, Marc (2008). Gibraltar: Conquered by No Enemy. Stroud, Glos: The History Press. ISBN 987-0-7509-3331-5.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid prefix (help) - Aldrich, Robert; Connell, John (1998). The Last Colonies. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521414616.

- Archer, Edward G. (2006). Gibraltar, Identity and Empire. London: Routledge. ISBN 9780415347969.

- Bradford, Ernle (1971). Gibraltar: The History of a Fortress. London: Rupert Hart-Davis. ISBN 0-246-64039-1.

- Collins, Roger (1998). Spain: an Oxford archaeological guide. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-285300-4.

- Finlayson, Clive (2006). The Fortifications of Gibraltar 1068-1945. Fortress 45. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84603-016-1.

- Gold, Peter (2012). Gibraltar: British or Spanish?. Routledge. ISBN 9780415347952.

- Hills, George (1974). Rock of Contention: A history of Gibraltar. London: Robert Hale & Company. ISBN 0-7091-4352-4.

- Jackson, William G. F. (1986). The Rock of the Gibraltarians. Cranbury, NJ: Associated University Presses. ISBN 0-8386-3237-8.

- Padró i Parcerisa, Josep (1980). Egyptian-type documents: from the Mediterranean littoral of the Iberian peninsula before the Roman conquest, Part 3. Leiden, Netherlands: Brill Archive. ISBN 978-90-04-06133-0.

- Shields, Graham J. (1987). Gibraltar. Oxford: Clio Press. ISBN 978-1-85109-045-7.

- Truver, Scott C. (1980). The Strait of Gibraltar and the Mediterranean, Volume 4. Alphen aan der Rijn, Netherlands: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. ISBN 978-90-286-0709-5.

Further reading

- Published in the 19th century

- Richard Ford (1855), "Gibraltar", A Handbook for Travellers in Spain (3rd ed.), London: J. Murray, OCLC 2145740

{{citation}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help)

- John Lomas, ed. (1889), "Gibraltar", O'Shea's Guide to Spain and Portugal (8th ed.), Edinburgh: Adam & Charles Black

{{citation}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help)

- Published in the 20th century

- "Gibraltar", Spain and Portugal (3rd ed.), Leipsic: Karl Baedeker, 1908, OCLC 1581249

{{citation}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help)