This is an old revision of this page, as edited by 50.137.10.231 (talk) at 03:17, 30 May 2013 (→Death toll). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 03:17, 30 May 2013 by 50.137.10.231 (talk) (→Death toll)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)

| The neutrality of this article is disputed. Relevant discussion may be found on the talk page. Please do not remove this message until conditions to do so are met. (November 2012) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

| Holodomor Голодомор | |

|---|---|

| Country | |

| Location | |

| Period | 1932–1933 |

| Total deaths | 1.8–7.5 million |

| Relief | Foreign relief rejected by the State. Respectively 176,200 and 325,000 tons of grains provided by the State as food and seed aids between February and July 1933. |

| Part of a series on the |

| Holodomor |

|---|

Historical backgroundFamines in the Soviet Union

Policies |

|

Responsible partiesSoviet Union |

| Investigation and understanding |

The Holodomor (Template:Lang-uk, "Extermination by hunger" or "Hunger-extermination"; derived from 'Морити голодом', "Starving someone" ) was a man-made famine in the Ukrainian SSR and adjacent Cossack territories between 1932 and 1933. During the famine, which is also known as the "Terror-Famine in Ukraine" and "Famine-Genocide in Ukraine", millions of Ukrainians and Cossacks died of starvation in a peacetime catastrophe unprecedented in the history of Ukraine.

The estimates of the death toll by scholars varied greatly. Recent research has narrowed the estimates to between 1.8 and 5 million, with modern consensus for a likely total of 3–3.5 million. According to the decision of Kyiv Appellation Court, the demographic losses due to the famine amounted to 10 million, with 3.9 million famine deaths, and a 6.1 million birth deficit.

Scholars disagree on the relative importance of natural factors and bad economic policies as causes of the famine and the degree to which the destruction of the Ukrainian peasantry was premeditated on the part of Joseph Stalin. Some scholars and politicians using the word Holodomor emphasize the man-made aspects of the famine, arguing that it was genocide; some consider the resultant loss of life comparable to the Holocaust. They argue that the Soviet policies were an attack on the rise of Ukrainian nationalism and therefore fall under the legal definition of genocide. Other scholars argue that the Holodomor was a consequence of the economic problems associated with radical economic changes implemented during the period of Soviet industrialization.

Etymology

The word Holodomor literally translated from Ukrainian means "death by hunger", or "to kill by hunger, to starve to death". Sometimes the expression is translated into English as "murder by hunger or starvation".

Holodomor is a compound of the Ukrainian words holod meaning "hunger" and mor meaning "plague". The expression moryty holodom means "to inflict death by hunger". The Ukrainian verb moryty (морити) means "to poison somebody, drive to exhaustion or to torment somebody". The perfective form of the verb moryty is zamoryty – "kill or drive to death by hunger, exhausting work".

The word was used in print as early as 1978 by Ukrainian immigrant organisations in the United States and Canada. However, in the USSR – of which Ukraine was a member – references to the famine were controlled, even after de-Stalinization in 1956. Historians could speak only of 'food difficulties', and the use of the very word golod/holod (hunger, famine) was forbidden.

Discussion of the Holodomor became more open as part of Glasnost in the late 1980s. In Ukraine, the first official use of the word was a December 1987 speech by Volodymyr Shcherbytskyi, First Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine, on the occasion of the republic's seventieth anniversary. An early public usage in the Soviet Union was in February 1988, in a speech by Oleksiy Musiyenko, Deputy Secretary for ideological matters of the party organisation of the Kiev branch of the Union of Soviet Writers in Ukraine. The term may have first appeared in print in the Soviet Union on 18 July 1988, in his article on the topic.

"Holodomor" is now an entry in the modern, two-volume dictionary of the Ukrainian language, published in 2004. The term is described as "artificial hunger, organised on a vast scale by a criminal regime against a country's population."

History

Scope and duration

| This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (January 2011) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

The famine had been predicted as far back as 1930 by academics and advisers to the Ukrainian SSR government, but little to no preventative action was taken.

The famine affected the Ukrainian SSR as well as the Moldavian ASSR (a part of the Ukrainian SSR at the time) in the spring of 1932 and from February to July 1933, with the greatest number of victims recorded in the spring of 1933.

Between 1926 and 1939, the Ukrainian population increased by 6.6%, whereas Russia and Belarus grew by 16.9% and 11.7%, respectively.

From the 1932 harvest Soviet authorities were able to procure only 4.3 million tons as compared with 7.2 million tons obtained from the 1931 harvest. Rations in town were drastically cut back, and in the winter of 1932–33 and spring of 1933 many urban areas were starved.

The urban workers were supplied by a rationing system (and therefore could occasionally assist their starving relatives of the countryside), but rations were gradually cut and by the spring of 1933, the urban residents also faced starvation. At the same time, workers were shown agitprop movies, where all peasants were portrayed as counterrevolutionaries hiding grain and potatoes at the time when workers, who are constructing the “bright future” of socialism, were starving. The first reports of mass malnutrition and deaths from starvation emerged from two urban areas of Uman, reported in January 1933 by the Vinnytsya and Kiev oblasts. By mid-January 1933 there were reports about mass “difficulties” with food in urban areas, which had been undersupplied through the rationing system, and deaths from starvation among people who were withdrawn from the rationing supply. This was to comply with the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine Decree December 1932. By the beginning of February 1933, according to reports from local authorities and Ukrainian GPU, the most affected area was Dnipropetrovsk Oblast, which also suffered from epidemics of typhus and malaria. Odessa and Kiev oblasts were second and third, respectively. By mid-March, most reports originated from Kiev Oblast.

By mid-April 1933, the Kharkiv Oblast reached the top of the most affected list, while Kiev, Dnipropetrovsk, Odessa, Vinnytsya, Donetsk oblasts and Moldavian SSR followed it. Reports about mass deaths from starvation, dated mid-May through the beginning of June 1933, originated from raions in Kiev and Kharkiv oblasts. The “less affected” list noted the Chernihiv Oblast and northern parts of Kiev and Vinnytsya oblasts. The Central Committee of the CP(b) of Ukraine Decree of 8 February 1933, said no hunger cases should have remained untreated. Local authorities had to submit reports about the numbers suffering from hunger, the reasons for hunger, number of deaths from hunger, food aid provided from local sources, and centrally provided food aid required. The GPU managed parallel reporting and food assistance in the Ukrainian SSR. (Many regional reports and most of the central summary reports are available from present-day central and regional Ukrainian archives.)

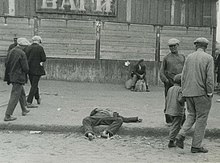

Evidence of widespread cannibalism was documented during the Holodomor. The Soviet regime printed posters declaring: "To eat your own children is a barbarian act." More than 2500 people were convicted of cannibalism during the Holodomor.

The Ukrainian Weekly, which was tracking the situation in 1933, reported the difficulties in communications and appalling situation in Ukraine. In addition, on 1 December 1933 the newspaper reported a mass protest planned to take place in Syracuse, New York.

Causes

Main article: Causes of the HolodomorThe reasons for the famine are a subject of scholarly and political debate. Some scholars suggest that the famine was a consequence of the economic problems associated with changes implemented during the period of Soviet industrialisation.

Collectivization also contributed to famine in 1932. Collectivization in the USSR, including the Ukrainian SSR, was not popular among the peasantry and forced collectivisation lead to numerous peasant revolts. The First Five-Year Plan changed the output expected from Ukrainian farms, from the familiar crop of grain to unfamiliar crops like sugar beets and cotton. In addition, the situation was exacerbated by poor administration of the plan and the lack of relevant general management. Significant amounts of grain remained unharvested, and – even when harvested – a significant percentage was lost during processing, transportation, or storage.

However, it has also been proposed by certain historians that the Soviet leadership used the famine to attack Ukrainian nationalism and thus may fall under the legal definition of genocide. For example, special and particularly lethal policies were adopted in and largely limited to Soviet Ukraine at the end of 1932 and 1933; "each of them may seem like an anodyne administrative measure, and each of them was certainly presented as such at the time, and yet each had to kill." A 2011 documentary, Genocide Revealed, presents evidence for the view that Stalin and his cohorts in the Communist regime (not necessarily the Russian people as a whole) deliberately targeted Ukrainians in the mass starvation of 1932–1933. For more about the Holodomor as an act of genocide, see the section below on the Genocide question.

Implementation and abuse

| This section needs expansion. You can help by making an edit requestadding to it . (November 2010) |

On 7 August 1932 a law came into force that stipulated that all food was state property and that mere possession of food was evidence of a crime. Among the most enthusiastic enforcers of the law were urban members of youth organisations, educated under the Soviet system, who fanned out into the countryside in order to prevent the "theft" of state property. They constructed and staffed watchtowers (over 700 in the Odessa region alone) to ensure that no peasants took food home from the fields. The youth brigades lived off the land, eating what they confiscated from the peasants. They often humiliated the starving peasants by forcing them to box each other for sport, or forcing them to crawl and bark like dogs. Under the pretext of grain confiscation, the brigades routinely raped women living alone.

Several thousand Ukrainian peasants managed to cross the river Dniester into Romania, and received asylum there. Many were killed during the crossing by Soviet border-guards.

Genocide question

Robert Conquest, the author of the Harvest of Sorrow, has stated that the famine of 1932–33 was a deliberate act of mass murder, if not genocide committed as part of Joseph Stalin's collectivisation program in the Soviet Union.

Conquest and R.W. Davies and Stephen G. Wheatcroft — believe that, had industrialisation been abandoned, the famine would have been "prevented" (Conquest), or at least significantly alleviated:

e regard the policy of rapid industrialisation as an underlying cause of the agricultural troubles of the early 1930s, and we do not believe that the Chinese or NEP versions of industrialisation were viable in Soviet national and international circumstances.

They see the leadership under Stalin as making significant errors in planning for the industrialisation of agriculture.

Dr. Michael Ellman of the University of Amsterdam argues that, in addition to deportations, internment in the Gulag and shootings (See: Law of Spikelets), there is evidence that Stalin used starvation as a weapon in his war against the peasantry. He analyses the actions of the Soviet authorities, two of commission and one of omission: (i) exporting 1.8 million tonnes of grain during the mass starvation (enough to feed more than five million people for one year), (ii) preventing migration from famine afflicted areas (which may have cost an estimated 150,000 lives) and (iii) making no effort to secure grain assistance from abroad (which caused an estimated 1.5 million excess deaths), as well as the attitude of the Stalinist regime in 1932–33 (that many of those starving to death were "counterrevolutionaries", "idlers" or "thieves" who fully deserved their fate). Based on this analysis he concludes, however, that the actions of Stalin's authorities against Ukrainians do not meet the standards of specific intent required to proof genocide as defined by the UN convention (with the notable exception of the case of Kuban Ukrainians). Ellman further concluded that if the relaxed definition of genocide is used, the actions of Stalin's authorities do fit such a definition of genocide. However, this more relaxed definition of genocide makes the latter the common historical event, according to Ellman.

Regarding the aforementioned actions taken by Stalin in the early 1930s, Ellman unambiguously states that, from the standpoint of contemporary international criminal law, Stalin is "clearly guilty" of "a series of crimes against humanity" and that, from the standpoint of national criminal law, the only way to defend Stalin from a charge of mass murder is "to argue he was ignorant of the consequences of his actions". He also rebukes Davies and Wheatcroft for, among other things, their "very narrow understanding" of intent. He states:

According to them, only taking an action whose sole objective is to cause deaths among the peasantry counts as intent. Taking an action with some other goal (e.g. exporting grain to import machinery) but which the actor certainly knows will also cause peasants to starve does not count as intentionally starving the peasants. However, this is an interpretation of 'intent' which flies in the face of the general legal interpretation.

Genocide scholar Adam Jones stresses that many of the actions of the Soviet leadership during 1931–32 should be considered genocidal. Not only did the famine kill millions, it took place against "a backdrop of persecution, mass execution, and incarceration clearly aimed at undermining Ukrainians as a national group". Norman Naimark, a historian at Stanford University who specialises in modern East European history, genocide and ethnic cleansing, argues that some of the actions of Stalin's regime, not only those during the Holodomor but also Dekulakization and targeted campaigns (with over 110,000 shot) against particular ethnic groups, can be looked at as genocidal. In 2006, the Security Service of Ukraine declassified more than 5 thousand pages of Holodomor archives. These documents suggest that the Soviet regime singled out Ukraine by not giving it the same humanitarian aid given to regions outside it.

The statistical distribution of famine's victims among the ethnicities closely reflects the ethnic distribution of the rural population of Ukraine Moldavian, Polish, German and Bulgarian population that mostly resided in the rural communities of Ukraine suffered in the same proportion as the rural Ukrainian population.

Author James Mace was one of the first to show that the famine constituted genocide. But British economist Stephen Wheatcroft, who studied the famine, believed that Mace's work debased the field of Russian studies. However, Wheatcroft's characterisation of the famine deaths as largely excusable, negligent homicide has been challenged by economist Steven Rosefielde, who states:

Grain supplies were sufficient to sustain everyone if properly distributed. People died mostly of terror-starvation (excess grain exports, seizure of edibles from the starving, state refusal to provide emergency relief, bans on outmigration, and forced deportation to food-deficit locales), not poor harvests and routine administrative bungling.

Timothy Snyder, Professor of History at Yale University, asserts that in 1933 "Joseph Stalin was deliberately starving Ukraine" through a "heartless campaign of requisitions that began Europe's era of mass killing". He argues the Soviets themselves "made sure that the term genocide, contrary to Lemkin's intentions, excluded political and economic groups". Thus the Ukrainian famine can be presented as "somehow less genocidal because it targeted a class, kulaks, as well as a nation, Ukraine".

In his 1953 speech the "father of the Genocide Convention", Dr Raphael Lemkin described "the destruction of the Ukrainian nation" as the "classic example of genocide", for "...the Ukrainian is not and never has been a Russian. His culture, his temperament, his language, his religion, are all different...to eliminate (Ukrainian) nationalism...the Ukrainian peasantry was sacrificed...a famine was necessary for the Soviet and so they got one to order...if the Soviet program succeeds completely, if the intelligentsia, the priest, and the peasant can be eliminated Ukraine will be as dead as if every Ukrainian were killed, for it will have lost that part of it which has kept and developed its culture, its beliefs, its common ideas, which have guided it and given it a soul, which, in short, made it a nation...This is not simply a case of mass murder. It is a case of genocide, of the destruction, not of individuals only, but of a culture and a nation."

he evidence of a large-scale famine was so overwhelming, was so unanimously confirmed by the peasants that the most "hard-boiled" local officials could say nothing in denial.

—William Henry Chamberlin, Christian Science Monitor, 29 May 1934

Mr. Chamberlin was a Moscow correspondent of the Christian Science Monitor for 10 years. In 1934 he was reassigned to the Far East. After he left the Soviet Union he wrote his account of the situation in Ukraine and North Caucasus (Poltava, Bila Tserkva, and Kropotkin). Chamberlin later published a couple of books: Russia's Iron Age and The Ukraine: A Submerged Nation.

Soviet and Western denial

Main article: Denial of the HolodomorHolodomor denials are the assertions that the 1932–1933 genocide in Soviet Ukraine either did not occur or did occur but was not a premeditated act. Denying the existence of the famine was the Soviet state's position, and reflected in both Soviet propaganda and the work of some Western journalists and intellectuals including Walter Duranty and Louis Fischer.

In modern politics

Main article: Holodomor in modern politics

The famine remains a politically charged topic; hence, heated debates are likely to continue for a long time. Until around 1990, the debates were largely between the so-called "denial camp" who refused to recognise the very existence of the famine or stated that it was caused by natural reasons (such as a poor harvest), scholars who accepted reports of famine but saw it as a policy blunder followed by the botched relief effort, and scholars who alleged that it was intentional and specifically anti-Ukrainian or even an act of genocide against the Ukrainians as a nation.

Nowadays, scholars agree that the famine affected millions. While it is also accepted that the famine affected other nationalities in addition to Ukrainians, the debate is still ongoing as to whether or not the Holodomor qualifies as an act of genocide. As far as the possible effect of the natural causes, the debate is restricted to whether the poor harvest or post-traumatic stress played any role at all and to what degree the Soviet actions were caused by the country's economic and military needs as viewed by the Soviet leadership.

In 2007, President Viktor Yushchenko declared he wants "a new law criminalising Holodomor denial", while Communist Party head Petro Symonenko said he "does not believe there was any deliberate starvation at all", and accused Yushchenko of "using the famine to stir up hatred". Few in Ukraine share Symonenko's interpretation of history and the number of Ukrainians who deny the famine or view it as caused by natural reasons is steadily falling.

On 10 November 2003 at the United Nations twenty-five countries including Russia, Ukraine and United States signed a joint statement on the seventieth anniversary of the Holodomor with the following preamble:

In the former Soviet Union millions of men, women and children fell victims to the cruel actions and policies of the totalitarian regime. The Great Famine of 1932–1933 in Ukraine (Holodomor), which took from 7 million to 10 million innocent lives and became a national tragedy for the Ukrainian people. In this regard we note activities in observance of the seventieth anniversary of this Famine, in particular organized by the Government of Ukraine.

Honouring the seventieth anniversary of the Ukrainian tragedy, we also commemorate the memory of millions of Russians, Kazakhs and representatives of other nationalities who died of starvation in the Volga River region, Northern Caucasus, Kazakhstan and in other parts of the former Soviet Union, as a result of civil war and forced collectivisation, leaving deep scars in the consciousness of future generations.

Nationwide, the political repression of 1937 (The Great Purge) under the guidance of Nikolay Yezhov were known for their ferocity and ruthlessness, but Lev Kopelev wrote, "In Ukraine 1937 began in 1933", referring to the comparatively early beginning of the Soviet crackdown in Ukraine.

While the famine was well documented at the time by journalist Gareth Jones, its reality has been disputed for ideological reasons.

An example of a late-era Holodomor objector is Canadian trade union activist and journalist Douglas Tottle, author of Fraud, Famine and Fascism: The Ukrainian Genocide Myth from Hitler to Harvard (published by Moscow-based Communist publisher Progress Publishers in 1987). Tottle claims that while there were severe economic hardships in Ukraine, the idea of the Holodomor was fabricated as propaganda by Nazi Germany and William Randolph Hearst to justify a German invasion.

On 26 April 2010, newly elected Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych, told Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe members that Holodomor was a common tragedy that struck Ukrainians and other Soviet peoples, and that it would be wrong to recognise the Holodomor as an act of genocide against one nation. He stated that "The Holodomor was in Ukraine, Russia, Belarus and Kazakhstan. It was the result of Stalin's totalitarian regime. But it would be wrong and unfair to recognize the Holodomor as an act of genocide against one nation." He has, however, referred to it as a crime, a tragedy, and an Armageddon, while maintaining use of the word "Holodomor" to describe the event. In response to Yanukovych's statements, the Our Ukraine Party alleged that Yanukovych directly violated Ukrainian law which defines the Holodomor as genocide against the Ukrainian people and makes public denial of the Holodomor unlawful. Our Ukraine Party also asserted that Yanukovych "ignored a ruling of 13 January 2010 by Kiev's Court of Appeal, which recognized the leaders of the totalitarian Bolshevik regime as those guilty of 'genocide against the Ukrainian national group in 1932–33 through the artificial creation of living conditions intended for its partial physical destruction.'" In 2012, Yanukovych referred to the Holodomor as a crime which caused fear and obedience.

Statements by governments

As of March 2008, dozens of governments have said the actions of the Soviet government are an act of genocide. The joint statement at the United Nations in 2003 has defined the famine as the result of actions and policies of the totalitarian regime that caused the deaths of millions of Ukrainians, Russians, Kazakhs and other nationalities in the USSR. On 28 November 2006, the Verkhovna Rada (Ukrainian Parliament) passed a law defining the Holodomor as a deliberate act of genocide and made public denial illegal. Even though in April 2010 newly elected president Yanukovych reversed Yushchenko's position on the Holodomor famine, the law has not been repealed and remains in force. On 23 October 2008, the European Parliament adopted a resolution that recognised the Holodomor as a crime against humanity.

On 12 January 2010, the court of appeals in Kyiv opened hearings into the "fact of genocide-famine Holodomor in Ukraine in 1932–33". In May 2009 the Security Service of Ukraine started a criminal case "in relation to the genocide in Ukraine in 1932–33". In a ruling on 13 January 2010 the court found Joseph Stalin and other Bolshevik leaders guilty of genocide against the Ukrainians. The court dropped criminal proceedings against the leaders: Stalin, Vyacheslav Molotov, Lazar Kaganovich, Stanislav Kosior, Pavel Postyshev and others, who all had died years before. This decision became effective on 21 January 2010.

On 27 April 2010, a draft Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe resolution declared the famine was caused by the "cruel and deliberate actions and policies of the Soviet regime" and was responsible for the deaths of "millions of innocent people" in Ukraine, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Moldova and Russia. Even though PACE found Stalin guilty of causing the famine, they rejected several amendments to the resolution, which proposed the Holodomor be recognized as an act of genocide against the Ukrainian people.

Remembrance

To honour those who perished in the Holodomor, monuments have been dedicated and public events held annually in Ukraine and worldwide.

Ukraine

Since 2006 Ukraine officially marks a Holodomor memorial day on the fourth Saturday of November.

In 2006, the Holodomor Remembrance Day took place on 25 November. Ukraine President Viktor Yushchenko directed, in decree No. 868/2006, that a minute of silence should be observed at 4 o'clock in the afternoon on that Saturday. The document specified that flags in Ukraine should fly at half-staff as a sign of mourning. In addition, the decree directed that entertainment events are to be restricted and television and radio programming adjusted accordingly.

In 2007, the 74th anniversary of the Holodomor was commemorated in Kyiv for three days on the Maidan Nezalezhnosti. As part of the three-day event, from 23–25 November, video testimonies of the communist regime's crimes in Ukraine, and documentaries by famous domestic and foreign film directors are being shown. Additionally, experts and scholars gave lectures on the topic. Additionally, on 23 November 2007, the National Bank of Ukraine issued a set of two commemorative coins remembering the Holodomor.

As of September 2009, Ukrainian schoolchildren take a more extensive course of the history of the Holodomor, plus fighters in the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists and Ukrainian Insurgent Army.

On 17 May 2010, President of Ukraine Viktor Yanukovych and President of Russia Dmitry Medvedev visited the Memorial to the Holodomor Victims in Kyiv to commemorate the victims of the famine.

Canada

The first public monument to the Holodomor was erected and dedicated in 1983 outside City Hall in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada, to mark the 50th anniversary of the famine-genocide. Since then, the fourth Saturday in November has in many jurisdictions been marked as the official day of remembrance for people who died as a result of the 1932–33 Holodomor and political repression.

On 22 November 2008, Ukrainian Canadians marked the beginning of National Holodomor Awareness Week. Citizenship, Immigration and Multiculturalism Minister Jason Kenney attended a vigil in Kiev. In November 2010, Prime Minister Stephen Harper visited the Holodomor memorial in Kiev, although Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych did not join him.

On 9 April 2009 the Province of Ontario unanimously passed bill 147, "The Holodomor Memorial Day Act", which calls for the fourth Saturday in November to be a day of remembrance. This was the first piece of legislation in the Province's history to be introduced with Tri-Partisan sponsorship: the joint initiators of the bill were Dave Levac, MPP for Brant (Liberal Party); Cheri DiNovo, MPP for Parkdale–High Park (NDP); and Frank Klees, MPP for Newmarket–Aurora (PC). MPP Levac was made a chevalier of Ukraine's Order of Merit.

On 2 June 2010 the Province of Quebec unanimously passed bill 390, "Memorial Day Act on the great Ukrainian famine and genocide (the Holodomor)".

On 25 September 2010, a new Holodomor monument was unveiled at St. Mary's Ukrainian Catholic Church, Mississauga, Canada, bearing the inscription "Holodomor: Genocide By Famine in Ukraine 1932–1933" and a section in Ukrainian bearing mention of the 10 million victims.

A monument to the Holodomor has been erected on Calgary's Memorial Drive, itself originally designated to honour Canadian servicemen of the First World War. The monument is located in the district of Renfrew near Ukrainian Pioneer Park, which pays tribute to the contributions of Ukrainian immigrants to Canada.

United States

The Ukrainian Weekly reported a meeting taking place on 27 February 1982 in the parish center of the Ukrainian Catholic National Shrine of the Holy Family in commemoration of the 50th Anniversary of the Great Famine caused by the Soviet authorities. On 20 March 1982 the Ukrainian Weekly also reported a multi-ethnic community meeting that was held on 15 February on the North Shore Drive at the Ukrainian Village in Chicago to commemorate the famine which took the lives of seven million Ukrainians. Other events in commemoration were held in other places around the United States as well.

On 29 May 2008, the city of Baltimore held a candlelight commemoration for the Holodomor at the War Memorial Plaza in front of City Hall. This ceremony was part of the larger international journey of the "International Holodomor Remembrance Torch", which began in Kiev and made its way though thirty-three countries. Twenty-two other US cities were also visited during the tour. Then-Mayor Sheila Dixon presided over the ceremony and declared 29 May to be "Ukrainian Genocide Remembrance Day in Baltimore". She referred to the Holodomor "among the worst cases of man's inhumanity towards man".

On 2 December 2008, a groundbreaking ceremony was held in Washington, D.C. for the Holodomor Memorial. On 13 November 2009, U.S. President Barack Obama released a statement on Ukrainian Holodomor Remembrance Day. In this he said that "remembering the victims of the man-made catastrophe of Holodomor provides us an opportunity to reflect upon the plight of all those who have suffered the consequences of extremism and tyranny around the world". NSC Spokesman Mike Hammer released a similar statement on 20 November 2010.

Also on 2 December 2008, St. Patrick's Cathedral in New York City had a ceremony for the Holodomor.

In 2011, the US date of remembrance of Holodomor was held on 19 November. The statement released by the Press Secretary reflects on the significance of this date. 2011 was a year of celebration for Ukraine – the 20-year anniversary of Ukraine's independence. Yet on this date "in the wake of this brutal and deliberate attempt to break the will of the people of Ukraine, Ukrainians showed great courage and resilience. The establishment of a proud and independent Ukraine twenty years ago shows the remarkable depth of the Ukrainian people's love of freedom and independence."

Images of Holodomor memorials

-

"Light the candle" event at a Holodomor memorial in Kiev

"Light the candle" event at a Holodomor memorial in Kiev

- Monument in Kiev Monument in Kiev

-

Memorial cross in Kharkiv, Ukraine

Memorial cross in Kharkiv, Ukraine

-

Memorial at the Andrushivka village cemetery, Vinnytsia Oblast, Ukraine

Memorial at the Andrushivka village cemetery, Vinnytsia Oblast, Ukraine

-

Memorial in Poltava Oblast, Ukraine

Memorial in Poltava Oblast, Ukraine

- Memorial cross in Dnipropetrovsk, Ukraine Memorial cross in Dnipropetrovsk, Ukraine

- Monument to victims of Holodomor in Luhansk, Ukraine Monument to victims of Holodomor in Luhansk, Ukraine

-

Monument to victims of Holodomor in Novoaydar, Luhansk Oblast, Ukraine

Monument to victims of Holodomor in Novoaydar, Luhansk Oblast, Ukraine

-

Roman Kowal's Holodomor Memorial in Winnipeg, Canada

Roman Kowal's Holodomor Memorial in Winnipeg, Canada

-

1983 Holodomor Monument in Edmonton, Canada (first in the world)

1983 Holodomor Monument in Edmonton, Canada (first in the world)

-

Monument near Chicago, Illinois, USA

Monument near Chicago, Illinois, USA

-

Holodomor Memorial in Windsor, Ontario, Canada

Holodomor Memorial in Windsor, Ontario, Canada

-

Holodomor Monument in Calgary, Canada

Holodomor Monument in Calgary, Canada

-

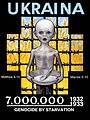

Poster by Australian artist Leonid Denysenko

Poster by Australian artist Leonid Denysenko

-

Stamp of Ukraine, 1993

See also

- Famine-33, 1991 film

- The Soviet Story, 2008 documentary film

- Bloodlands: Europe Between Stalin and Hitler, 2010 book by historian Timothy D. Snyder

- Soviet famine of 1932–1933

- Great Chinese Famine, widespread famine in 1958–1961 due to drought, poor weather conditions, and the policies of the communist government

Notes and references

- Davies & Wheatcroft 2010, pp. 479–484.

- Jones, Adam (2010). Genocide: A Comprehensive Introduction. Taylor & Francis. p. 194. ISBN 9780415486187.

- Graziosi, Andrea (2005). LES FAMINES SOVIÉTIQUES DE 1931-1933 ET LE HOLODOMOR UKRAINIEN. Cahier du Monde Russe. p. 464.

- Davies 2006, p. 145.

- Baumeister 1999, p. 179.

- Sternberg & Sternberg 2008, p. 67.

- ^ "The famine of 1932–33", Encyclopædia Britannica. Quote: "The Great Famine (Holodomor) of 1932–33—a man-made demographic catastrophe unprecedented in peacetime. Of the estimated six to eight million people who died in the Soviet Union, about four to five million were Ukrainians... Its deliberate nature is underscored by the fact that no physical basis for famine existed in Ukraine... Soviet authorities set requisition quotas for Ukraine at an impossibly high level. Brigades of special agents were dispatched to Ukraine to assist in procurement, and homes were routinely searched and foodstuffs confiscated... The rural population was left with insufficient food to feed itself."

- Wheatcroft 2001a.

- Conquest 2002.

- "Наливайченко назвал количество жертв голодомора в Украине" (in Russian). LB.ua. 14 January 2010. Retrieved 21 July 2012.

- Davies & Wheatcroft 2002, p. 77. "he drought of 1931 was particularly severe, and drought conditions continued in 1932. This certainly helped to worsen the conditions for obtaining the harvest in 1932".

- Tauger 2001, p. 46. "This famine therefore resembled the Irish famine of 1845–1848, but resulted from a litany of natural disasters that combined to the same effect as the potato blight had ninety years before, and in a similar context of substantial food exports".

- Engerman 2003, p. 194.

- Zisels, Josef; Kharaz, Halyna (11 November 2007). "Will Holodomor receive the same status as the Holocaust?". "Maidan" Alliance. Retrieved 21 July 2012.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher= - ^ Finn, Peter (27 April 2008). "Aftermath of a Soviet Famine". WashingtonPost.com. Retrieved 21 July 2012.

There are no exact figures on how many died. Modern historians place the number between 2.5 million and 3.5 million. Yushchenko and others have said at least 10 million were killed.

- ^ Marples, David (30 November 2005). "The Great Famine Debate Goes On..." Edmonton Journal. Retrieved 21 July 2012. Cite error: The named reference "marples2005" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Kulchytsky, Stanislav (6 March 2007). "Holodomor of 1932–33 as genocide: gaps in the evidential basis". Den. Retrieved 22 July 2012. Part 1 – Part 2 – Part 3 – Part 4

- ^ Bilinsky 1999.

- ^ Kulchytsky, Stanislav. "Holodomor-33: Why and how?". Zerkalo Nedeli (25 November – 1 December 2006). Retrieved 21 July 2012. Russian version; Ukrainian version.

- ^ Wheatcroft 2001b, p. 885.

- ^ 'Stalinism' was a collective responsibility – Kremlin papers, The News in Brief, University of Melbourne, 19 June 1998, Vol 7 No 22

- Werth 2010, p. 396.

- ^ Fawkes, Helen (24 November 2006). "Legacy of famine divides Ukraine". BBC News. Retrieved 21 July 2012.

- Hryshko 1978.

- Dolot 1985.

- Hadzewycz, Zarycky & Kolomayets 1983.

- Bilinsky, Yaroslav (July 1983 url = http://www.unz.org/Pub/ProblemsCommunism-1983jul-00001). "Shcherbytskyi, Ukraine, and Kremlin Politics". Problems of Communism.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); External link in|date=|date=(help) - Graziosi, Andrea (2004–2005). "The Soviet 1931–1933 Famines and the Ukrainian Holodomor: Is a New Interpretation Possible, and What Would Its Consequences Be?". Harvard Ukrainian Studies. 27 (1–4): 97–115. JSTOR 41036863.

- O. H. Musiienko, "Hromadians'ka pozytsiia literatury i perebudova" (The Civic Position of Literature and Perestroika), Literaturna Ukraina, 18 February 1988, pp. 7–8;

- U.S. Commission on the Ukraine Famine (1988), Investigation of the Ukrainian Famine 1932–1933, Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office, p. 67, retrieved 27 July 2012

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|separator=ignored (help) - Mace 2008, p. 132.

- Голодомор, in "Velykyi tlumachnyi slovnyk suchasnoi ukrainsʹkoi movy: 170 000 sliv", chief ed. V. T. Busel, Irpin, Perun (2004), ISBN 966-569-013-2

- Dawood, M (2012). "Hidden agendas and hidden illness". Diversity and Equality in Health and Care. 9 (4): 297–8.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ""Голодомор 1932–33 років в Україні: документи і матеріали"/ Упорядник Руслан Пиріг; НАН України.Ін-т історії України.-К.:Вид.дім "Києво-Могилянська академія", "Famine in Ukraine 1932–33: documents and materials / compiled by Ruslan Pyrig National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine. Institute of History of Ukraine. -K.:section Kiev-Mohyla Academy 2007". Archives.gov.ua. Retrieved 7 September 2012.

- Davies & Wheatcroft 2010, p. 204.

- "University of Toronto Data Library Service".

- "Demoscope Weekly".

- Davies & Wheatcroft 2010, p. 470, 476.

- Davies & Wheatcroft 2010, p. xviii.

- Холодомор – 2009. Retrieved 6 November 2010.

- "Голод 1932–1933 років на Україні: очима істориків, мовою документів". Archives.gov.ua. Retrieved 7 September 2012.

- Сокур, Василий (21 November 2008). %5b%5b:Template:Ru icon%5d%5d "Выявленным во время голодомора людоедам ходившие по селам медицинские работники давали отравленные "приманки" — кусок мяса или хлеба". Facts and Commentaries. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

{{cite news}}: Check|url=value (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|trans_title=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) The author suggests that never in the history of mankind was cannibalism so widespread as during the Holodomor. - Várdy & Várdy 2007.

- Holodomor Archives and Sources: The State of the Art by Hennadii Boriak "The Harriman Review Vol. 16, No. 2" 2008 page 30

- Snyder 2010, pp. 42–46.

- Genocide Revealed. Retrieved 3 December 2011.

- Snyder 2010, pp. 38–39.

- Іvanushenko, Gennadіy (2 February 2011). "Генерал Василь Филонович: "Я присягав на Конституцію УНР..."" (in Ukrainian). Research Center of the Liberation Movement. Retrieved 20 July 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - Conquest 1999.

- Davies & Wheatcroft 2006.

- Ellman 2005.

- ^ Ellman 2007.

- Jones 2010, pp. 136–7. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFJones2010 (help)

- Naimark 2010, pp. 133–135.

- "Служба безпеки України". Ssu.kmu.gov.ua. Retrieved 7 September 2012.

- "SBU documents show that Moscow singled out Ukraine in famine". 5 Kanal. 22 November 2006. Retrieved 22 July 2012.

- ^ Kulchytsky & Yefimenko 2003, pp. 63–72.

- Marples 2007, p. 64.

- Rosefielde 2009, p. 259.

- Snyder 2010, p. vii.

- Snyder 2010, p. 413.

- Lemkin, Raphael (1953). "Soviet Genocide in the Ukraine" (PDF). Retrieved 22 July 2012. Raphael Lemkin Papers, The New York Public Library, Manuscripts and Archives Division, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundation, Raphael Lemkin ZL-273. Reel 3. Published in L.Y. Luciuk (ed), Holodomor: Reflections on the Great Famine of 1932–1933 in Soviet Ukraine (Kingston: The Kashtan Press, 2008).

- Weiss-Wendt 2005.

- Chamberlin, William Henry (20 March 1983). "Famine proves potent weapon in Soviet policy" (PDF). The Ukrainian Weekly. 51 (12): 6. Retrieved 22 July 2012.

- William Henry Chamberlin. "The Ukraine: A Submerged Nation, published in 1944". Openlibrary.org. Retrieved 7 September 2012.

- What Is the Ukraine Famine Disaster of 1932–1933?

- ^ Radzinsky 1996, pp. 256–9.

- Conquest 2001, p. 96.

- Pipes 1995, pp. 232–6.

- Editorial (14 July 2002). "Famine denial" (PDF). The Ukrainian Weekly. 70 (28): 6. Retrieved 22 July 2012.

- Mace 2004, p. 93.

- Century of Genocide: Critical Essays and Eyewitness Accounts. p. 93. ISBN 0-415-94429-5.

- Dmytro Horbachov, Fullest Expression of Pure feeling, Welcome to Ukraine, 1998, No 1.

- Wilson 2002, p. 144.

- Getty, J. Arch (2000). "The Future Did Not Work". The Atlantic Monthly. 285 (3): 113.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - See also the acrimonious exchange between Tauger and Conquest.

- Cite error: The named reference

Sheeterwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - Большинство украинцев считают Голодомор актом геноцида, Korrespondent.net, 20 November 2007

- ^ "30 U.N. member-states sign joint declaration on Great Famine" (PDF). The Ukrainian Weekly. 71 (46): 1, 20. 16 November 2003. Retrieved 22 July 2012.

- Subtelny 2002, p. 418. sfn error: no target: CITEREFSubtelny2002 (help)

- Tottle 1987.

- Interfax-Ukraine (27 April 2010). "Yanukovych: Famine of 1930s was not genocide against Ukrainians". KyivPost.com. Retrieved 21 July 2012.

- ^ Motyl, Alexander J. (29 November 2012). "Yanukovych and Stalin's Genocide". World Affairs. Retrieved 2 December 2012.

- ^ Interfax-Ukraine (27 April 2010). "Our Ukraine Party: Yanukovych violated law on Holodomor of 1932–1933". KyivPost.com. Retrieved 22 July 2012.

- Sources differ on interpreting various statements from different branches of different governments as to whether they amount to official recognition of the famine as genocide. For example, after the statement issued by Latvia's Saeima on 13 March 2008, the total number of countries is given as 19 ("Латвія визнала Голодомор ґеноцидом". BBC Ukrainian. 13 March 2008. Retrieved 23 July 2012.), 16 ("После продолжительных дебатов Сейм Латвии признал Голодомор геноцидом украинцев". Korrespondent.net Template:Uk icon. 13 March 2008. Retrieved 23 July 2012.), "more than 10" ("Латвія визнала Голодомор 1932–33 рр. геноцидом українців". Korrespondent.net Template:Ru icon. 14 March 2008. Retrieved 23 July 2012.)

- Mordini & Green 2009, p. x.

- Pourchot 2008, p. 98.

- ^ "Yanukovych reverses Ukraine's position on Holodomor famine". RIA Novosti. 27 April 2010. Retrieved 22 July 2012.

- "Commemoration of the Holodomor, the artificial famine in Ukraine (1932–1933)". European Parliament. 23 October 2008. Retrieved 22 July 2012.

- "European Parliament resolution of 23 October 2008 on the commemoration of the Holodomor, the Ukraine artificial famine (1932–1933)". European Parliament. 23 October 2008. Retrieved 21 July 2012.

- Interfax-Ukraine (12 January 2010). "Holodomor court hearings begin in Ukraine". KyivPost.com. Retrieved 21 July 2012.

- "Yushchenko brings Stalin to court over genocide". RT.com. 14 January 2010. Retrieved 21 July 2012.

- Interfax-Ukraine (21 January 2010). "Sentence to Stalin, his comrades for organizing Holodomor takes effect in Ukraine". KyivPost.com. Retrieved 21 July 2012.

- "PACE finds Stalin regime guilty of Holodomor, does not recognize it as genocide". RIA Novosti. 28 April 2010. Retrieved 21 July 2012.

- Putinism: The Slow Rise of a Radical Right Regime in Russia by Marcel Van Herpen], Palgrave Macmillan, 2013, ISBN 1137282800

- Yushchenko, Viktor. Decree No. 868/2006 by President of Ukraine. Regarding the Remembrance Day in 2006 for people who died as a result of Holodomor and political repressions Template:Uk icon

- "Ceremonial events to commemorate Holodomor victims to be held in Kyiv for three days". National Radio Company of Ukraine. URL Accessed 25 November 2007

- Commemorative Coins "Holodomor – Genocide of the Ukrainian People". National Bank of Ukraine.URL Accessed 25 June 2008

- "Schoolchildren to study in detail about Holodomor and OUN-UPA". ZIK–Western Information Agency. 12 June 2009. Retrieved 22 July 2012.

- Interfax-Ukraine (17 May 2010). "Medvedev, Yanukovych lay wreaths at Eternal Flame, Holodomor Memorial". KyivPost.com. Retrieved 21 July 2012.

- Bradley, Lara. "Ukraine's 'Forced Famine' Officially Recognized. The Sundbury Star. 3 January 1999. URL Accessed 12 October 2006

- "Ukrainian-Canadians mark famine's 75th anniversary". CTV.ca. 22 November 2008. Retrieved 22 July 2012.

- "Ontario MPP gets Ukrainian knighthood for bill honouring victims of famine". The Canadian Press. 20 November 2010. Retrieved 22 July 2012.

- "Quebec Passes Bill Recognizing Holodomor as a Genocide". Ukrainian Canadian Congress. 3 June 2010. Retrieved 22 July 2012.

- "Holodomor Monument – Пам'ятник Голодомору 1932–33". St. Mary's Ukrainian Catholic Church. Retrieved 22 July 2012.

- Berg, Tabitha (6 June 2008). "International Holodomor Remembrance Torch in Baltimore Commemorates Ukrainian Genocide". eNewsChannels. Retrieved 22 July 2012.

- Bihun, Yaro (7 December 2008). "Site of Ukrainian Genocide Memorial in D.C. is dedicated" (PDF). The Ukrainian Weekly. 76 (49): 1, 8. Retrieved 22 July 2012.

- "Remembrance of Holodomor in Ukraine will help prevent such tragedy in future, says Obama". Interfax-Ukraine. 14 November 2009. Retrieved 22 July 2012.

- Statement by the President on the Ukrainian Holodomor Remembrance Day, whitehouse.gov (13 November 2009)

- "Statement by the NSC Spokesman Mike Hammer on Ukraine's Holodomor Remembrance Day". WhiteHouse.gov. 20 November 2010. Retrieved 22 July 2012.

- "Statement by the Press Secretary on Ukrainian Holodomor Remembrance Day". WhiteHouse.gov. 19 November 2011. Retrieved 22 July 2012.

Bibliography

- Baumeister, Roy (1999). Evil: Inside Human Violence and Cruelty. New York, NY: Henry Holt and Company. ISBN 978-0-805-07165-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bilinsky, Yaroslav (1999). "Was the Ukrainian Famine of 1932–1933 Genocide?". Journal of Genocide Research. 1 (2): 147–156.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Conquest, Robert (1999). "Comment on Wheatcroft". Europe-Asia Studies. 51 (8): 1479–1483. JSTOR 153839.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Conquest, Robert (2001). Reflections on a Ravaged Century (New ed.). New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-32086-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Conquest, Robert (2002) . The Harvest Of Sorrow: Soviet Collectivisation and the Terror-Famine. London: Pimlico. ISBN 978-0-712-69750-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Davies, Robert W.; Wheatcroft, Stephen G. (2002). "The Soviet Famine of 1932–33 and the Crisis in Agriculture". In Stephen G. Wheatcroft (ed.). Challenging Traditional Views of Russian History. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-333-75461-0.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - Davies, Robert W.; Wheatcroft, Stephen G. (2006). "Stalin and the Soviet Famine of 1932–33: A Reply to Ellman". Europe-Asia Studies. 58 (4): 625–633. JSTOR 20451229.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Davies, Robert W.; Wheatcroft, Stephen G. (2010). The Years of Hunger: Soviet Agriculture 1931–1933. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-230-23855-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Davies, Norman (2006). Europe East and West. London: Jonathan Cape. ISBN 978-0-224-06924-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Dolot, Miron (1985). Execution by Hunger: The Hidden Holocaust. New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-30416-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Ellman, Michael (2005). "The Role of Leadership Perceptions and of Intent in the Soviet Famine of 1931–1934" (PDF). Europe-Asia Studies. 57 (6): 823–41.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Ellman, Michael (2007). "Stalin and the Soviet Famine of 1932–33 Revisited" (PDF). Europe-Asia Studies. 59 (4): 663–693.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Engerman, David (2003). Modernization from the Other Shore: American Intellectuals and the Romance of Russian Development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-01151-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hadzewycz, Roma; Zarycky, George B.; Kolomayets, Martha, eds. (1983). The Great Famine in Ukraine: The Unknown Holocaust. Jersey City, NJ: Ukrainian National Association.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hryshko, Vasyl (1978). Ukrains'kyi 'Holokast', 1933. New York, NY: DOBRUS; Toronto: SUZHERO.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Jones, Adam (2010). Genocide: A Comprehensive Introduction (2nd ed.). Milton Park: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-48619-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kulchytsky, Stanislav; Yefimenko, Hennadiy (2003). %5b%5b:Template:Uk icon%5d%5d Демографічні наслідки голодомору 1933 р. в Україні. Всесоюзний перепис 1937 р. в Україні: документи та матеріали. Kiev: Institute of History. ISBN 966-02-3014-1.

{{cite book}}: Check|url=value (help); Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - Laar, Mart (2010). The Power of Freedom: Central and Eastern Europe after 1945. Tallinn: Unitas Foundation. ISBN 978-9-949-18858-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Mace, James E. (2004). "Soviet Man-Made Famine in Ukraine". In Totten, Samuel; Parsons, William S.; Charny, Israel W. (eds.). Century of Genocide: Critical Essays and Eyewitness Accounts. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-94430-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Mace, James E. (2008). Ваші мертві вибрали мене... Kiev: Vyd-vo ZAT "Ukraïns'ka pres-hrupa". ISBN 978-9-668-15213-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) (A collection of Mace's articles and columns published in Den from 1993–2004). - Marples, David R. (2007). Heroes and Villains: Creating National History in Contemporary Ukraine. Budapest: Central European University Press. ISBN 978-9-637-32698-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Meslé, France; Pison, Gilles; Vallin, Jacques (2005). "France-Ukraine: Demographic Twins Separated by History" (PDF). Population and societies (413): 1–4.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Mordini, Emilio; Green, Manfred (2009). Identity, Security and Democracy: The Wider Social and Ethical Implications of Automated Systems for Human Identification (PDF). Amsterdam: IOS Press. ISBN 978-1-586-03940-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Naimark, Norman M. (2010). Stalin's Genocides. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-14784-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Pipes, Richard (1995). Russia Under the Bolshevik Regime. New York, NY: Vintage Books. ISBN 978-0679761846.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Potocki, Robert (2003). Polityka państwa polskiego wobec zagadnienia ukraińskiego w latach 1930–1939 (in Polish and English summary). Lublin: Instytut Europy Środkowo-Wschodniej. ISBN 978-8-391-76154-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - Pourchot, Georgeta (2008). Eurasia Rising: Democracy and Independence in the Post-Soviet Space. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0-275-99916-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Radzinsky, Edvard (1996). Stalin: The First In-depth Biography Based on Explosive New Documents from Russia's Secret Archives. London: Hodder & Stoughton. ISBN 978-0-340-60619-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Rosefielde, Steven (1983). "Excess Mortality in the Soviet Union: A Reconsideration of the Demographic Consequences of Forced Industrialization, 1929–1949". Soviet Studies. 35 (3): 385–409. JSTOR 151363.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Rosefielde, Steven (2009). Red Holocaust. Milton Park: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-77756-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Snyder, Timothy (2010). Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin. London: The Bodley Head. ISBN 978-0-224-08141-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Sternberg, Robert J.; Sternberg, Karin (2008). The Nature of Hate. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-72179-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Subtelny, Orest (2009) . Ukraine: A History (4th revised ed.). Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-1-442-60991-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Tauger, Mark B. (1991). "The 1932 Harvest and the Famine of 1933" (PDF). Slavic Review. 50 (1): 70–89.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Tauger, Mark B. (2001). "Natural Disasters and Human Actions in the Soviet Famine of 1931–1933". The Carl Beck Papers in Russian & East European Studies (1506). University of Pittsburgh.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Tottle, Douglas (1987). Fraud, Famine, and Fascism: the Ukrainian Genocide Myth from Hitler to Harvard. Toronto: Progress Books. ISBN 0-919396-51-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Vallin, Jacques; Meslé, France; Adamets, Serguei; Pyrozhkov, Serhii (2002). "A New Estimate of Ukrainian Population Losses during the Crises of the 1930s and 1940s" (PDF). Population Studies. 56 (3): 249–264.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Várdy, Steven Béla; Várdy, Agnes Huszár (2007). "Cannibalism in Stalin's Russia and Mao's China" (PDF). East European Quarterly. 41 (2): 223–238.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Weiss-Wendt, Anton (2005). "Hostage of Politics: Raphael Lemkin on 'Soviet Genocide'" (PDF). Journal of Genocide Research. 7 (4): 551–559.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Werth, Nicolas (2010). "Mass deportations, Ethnic Cleansing, and Genocidal Politics in the Latter Russian Empire and the USSR". In Donald Bloxham; A. Dirk Moses (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Genocide Studies. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-199-23211-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Wheatcroft, Stephen G. (2000), A Note on Demographic Data as an Indicator of the Tragedy of the Soviet Village, 1931–33 (draft) (PDF), retrieved 31 July 2012

{{citation}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|separator=ignored (help) - Wheatcroft, Stephen G. (2001a). "Current knowledge of the level and nature of mortality in the Ukrainian famine of 1931–3". In V. Vasil'ev; Y. Shapovala (eds.). Komandiri velikogo golodu: Poizdki V.Molotova I L.Kaganovicha v Ukrainu ta na Pivnichnii Kavkaz, 1932–1933 rr. Kyiv: Geneza.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - Уиткрофт, С. (2001b). "О демографических свидетельствах трагедии советской деревни в 1931–1933 гг.". In V.P. Danilov; et al. (eds.). Трагедия советской деревни: Коллективизация и раскулачивание 1927–1939 гг.: Документы и материалы (in Russian). Vol. 3. Moscow: ROSSPEN. ISBN 5-8243-0225-1.

{{cite book}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|editor=(help); External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|trans_chapter=ignored (|trans-chapter=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Wheatcroft, Stephen G. (2004). "Towards Explaining the Soviet Famine of 1931–1933: Political and Natural Factors in Perspective". Food and Foodways. 12 (2–3): 107–136.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Wilson, Andrew (2002). The Ukrainians: Unexpected Nation (2nd ed.). New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-09309-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

Further reading

Declarations and legal acts

- Findings of the Commission on the Ukraine Famine, U.S. Commission on the Ukraine Famine, Report to Congress. Adopted by the Commission, 19 April 1988

- Joint declaration at the United Nations in connection with 70th anniversary of the Great Famine in Ukraine 1932–1933

- Address of the Verkhovna Rada to the Ukrainian nation on commemorating the victims of Holodomor 1932–1933 (in Ukrainian)

Books and articles

- Chastushka Journal of American folklore, Volume 89 Houghton, Mifflin, and Co., 1976

- Fürst, Juliane. Stalin's Last Generation: Soviet Post-War Youth and the Emergence of Mature Socialism Oxford University Press. 30 September 2010. ISBN 978-0-19-957506-0

- Kowalski, Ludwik. Hell on Earth: Brutality and Violence Under the Stalinist Regime Wasteland Press 30 July 2008. ISBN 978-1-60047-232-9

- Ammende, Ewald, Human life in Russia, (Cleveland: J.T. Zubal, 1984), Reprint, Originally published: London, England: Allen & Unwin, 1936.

- The Black Deeds of the Kremlin: a white book, S.O. Pidhainy, Editor-In-Chief, (Toronto: Ukrainian Association of Victims of Russian-Communist Terror, 1953), (Vol. 1 Book of testimonies. Vol. 2. The Great Famine in Ukraine in 1932–1933).

- Davies, R.W., The Socialist offensive: the collectivization of Soviet agriculture, 1929–1930, (London: Macmillan, 1980).

- Der ukrainische Hunger-Holocaust: Stalins verschwiegener Volkermond 1932/33 an 7 Millionen ukrainischen Bauern im Spiegel geheimgehaltener Akten des deutschen Auswartigen Amtes, (Sonnebuhl: H. Wild, 1988), By Dmytro Zlepko. .

- Luciuk, L. Y. (ed), "Holodomor: Reflections on the Great Famine of 1932–1933 in Soviet Ukraine" (Kingston: Kashtan Press, 200()

- Dolot, Miron, Who killed them and why?: in remembrance of those killed in the Famine of 1932–1933 in Ukraine, (Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University, Ukrainian Studies Fund, 1984).

- Dushnyk, Walter, 50 years ago: the famine holocaust in Ukraine, (New York: Toronto: World Congress of Free Ukrainians, 1983).

- Famine in the Soviet Ukraine 1932–1933: a memorial exhibition, Widener Library, Harvard University, prepared by Oksana Procyk, Leonid Heretz, James E. Mace (Cambridge, Mass: Harvard College Library, distributed by Harvard University Press, 1986).

- Famine in Ukraine 1932–33, edited by Roman Serbyn and Bohdan Krawchenko (Edmonton: Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies, 1986). (Selected papers from a conference held at the Universite du Quebec a Montreal in 1983).

- Gregorovich, Andrew, “Black Famine in Ukraine 1932–33: A Struggle for Existence”, Forum: A Ukrainian Review, No. 24, (Scranton: Ukrainian Workingmen's Association, 1974).

- Halii, Mykola, Organized famine in Ukraine, 1932–1933, (Chicago: Ukrainian Research and Information Institute, 1963).

- Holod na Ukraini, 1932–1933: vybrani statti, uporiadkuvala Nadiia Karatnyts'ka, (New York: Suchasnist', 1985).

- Hlushanytsia, Pavlo, "Tretia svitova viina Pavla Hlushanytsi == The third world war of Pavlo Hlushanytsia, translated by Vera Moroz, (Toronto: Anabasis Magazine, 1986). .

- Holod 1932–33 rokiv na Ukraini: ochyma istorykiv, movoij dokumentiv, (Kiev: Vydavnytstvo politychnoyi literatury Ukrainy, 1990).

- Hryshko, Vasyl, The Ukrainian Holocaust of 1933, Edited and translated by Marco Carynnyk, (Toronto: Bahrianyi Foundation, SUZHERO, DOBRUS, 1983).

- International Commission of Inquiry into the 1932–33 Famine in Ukraine, Proceedings , 23–27 May 1988, Brussels, Belgium, [Jakob W.F. Sundberg, President; Legal Counsel, World Congress of Free Ukrainians: John Sopinka, Alexandra Chyczij; Legal Council for the Commission, Ian A. Hunter, 1988.

- International Commission of Inquiry into the 1932–33 Famine in Ukraine. Proceedings , 21 October – 5 November 1988, New York City, , 1988.

- International Commission of Inquiry into the 1932–1933 Famine in Ukraine. Final report, , 1990. .

- Kalynyk, Oleksa, Communism, the enemy of mankind: documents about the methods and practise of Russian Bolshevik occupation in Ukraine, (London, England: The Ukrainian Youth Association in Great Britain, 1955).

- Klady, Leonard, “Famine Film Harvest of Despair”, Forum: A Ukrainian Review, No. 61, Spring 1985, (Scranton: Ukrainian Fraternal Association, 1985).

- Kolektyvizatsia і Holod na Ukraini 1929–1933: Zbirnyk documentiv і materialiv, Z.M. Mychailycenko, E.P. Shatalina, S.V. Kulcycky, eds., (Kiev: Naukova Dumka, 1992).

- Kostiuk, Hryhory, Stalinist rule in Ukraine: a study of the decade of mass terror, 1929–1939, (Munich: Institut zur Erforschung der UdSSSR, 1960).

- Kovalenko, L.B. & Maniak, B.A., eds., Holod 33: Narodna knyha-memorial, (Kiev: Radians'kyj pys'mennyk, 1991).

- Krawchenko, Bohdan, Social change and national consciousness in twentieth-century Ukraine, (Basingstoke: Macmillan in association with St. Anthony's College, Oxford, 1985).

- Luciuk, Lubomyr (and L Grekul), Holodomor: Reflections on the Great Famine of 1932–1933 in Soviet Ukraine (Kashtan Press, Kingston, 2008.)

- Lettere da Kharkov: la carestia in Ucraina e nel Caucaso del Nord nei rapporti dei diplomatici italiani, 1932–33, a cura di Andrea Graziosi, (Torino: Einaudi, 1991).

- Mace, James E., Communism and the dilemma of national liberation: national communism in Soviet Ukraine, 1918–1933, (Cambridge, Mass.: Distributed by Harvard University Press for the Ukrainian Research Institute and the Ukrainian Academy of Arts and Sciences in the U.S., 1983).

- Makohon, P., Svidok: Spohady pro 33-ho, (Toronto: Anabasis Magazine, 1983).

- Martchenko, Borys, La famine-genocide en Ukraine: 1932–1933, (Paris: Publications de l'Est europeen, 1983).

- Marunchak, Mykhailo H., Natsiia v borot'bi za svoie isnuvannia: 1932 і 1933 v Ukraini і diiaspori, (Winnipeg: Nakl. Ukrains'koi vil'noi akademii nauk v Kanadi, 1985).

- Memorial, compiled by Lubomyr Y. Luciuk and Alexandra Chyczij; translated into English by Marco Carynnyk, (Toronto: Published by Kashtan Press for Canadian Friends of “Memorial”, 1989). .

- Mishchenko, Oleksandr, Bezkrovna viina: knyha svidchen', (Kiev: Molod', 1991).

- Oleksiw, Stephen, The agony of a nation: the great man-made famine in Ukraine, 1932–1933, (London: The National Committee to Commemorate the 50th Anniversary of the Artificial Famine in Ukraine, 1932–1933, 1983).

- Pavel P. Postyshev, envoy of Moscow in Ukraine 1933–1934, , (Toronto: World Congress of Free Ukrainians, Secretariat, , The 1932–33 Famine in Ukraine research documentation).

- Pidnayny, Alexandra, A bibliography of the great famine in Ukraine, 1932–1933, (Toronto: New Review Books, 1975).

- Pravoberezhnyi, Fedir, 8,000,000: 1933-i rik na Ukraini, (Winnipeg: Kultura і osvita, 1951).

- Senyshyn, Halyna, Bibliohrafia holody v Ukraini 1932–1933, (Ottawa: Montreal: UMMAN, 1983).

- Solovei, Dmytro, The Golgotha of Ukraine: eye-witness accounts of the famine in Ukraine, compiled by Dmytro Soloviy, (New York: Ukrainian Congress Committee of America, 1953).

- Stradnyk, Petro, Pravda pro soviets'ku vladu v Ukraini, (New York: N. Chyhyryns'kyi, 1972).

- Taylor, S.J., Stalin's apologist: Walter Duranty, the New York Time's man in Moscow, (New York: Oxford University Press, 1990).

- The Foreign Office and the famine: British documents on Ukraine and the great famine of 1932–1933, edited by Marco Carynnyk, Lubomyr Y. Luciuk and Bohdan Kor.

- The man-made famine in Ukraine (Washington D.C.: American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research, 1984). .

- United States, Commission on the Ukraine Famine. Investigation of the Ukrainian Famine, 1932–1933: report to Congress / Commission on the Ukraine Famine, . (Washington D.C.: U.S. G.P.O.: For sale by the Supt. of Docs, U.S. G.P.O., 1988), (Dhipping list: 88-521-P).

- United States, Commission on the Ukrainian Famine. Oral history project of the Commission on the Ukraine Famine, James E. Mace and Leonid Heretz, eds. (Washington, D.C.: Supt. of Docs, U.S. G.P.O., 1990).

- Velykyi holod v Ukraini, 1932–33: zbirnyk svidchen', spohadiv, dopovidiv ta stattiv, vyholoshenykh ta drukovanykh v 1983 rotsi na vidznachennia 50-littia holodu v Ukraini—The Great Famine in Ukraine 1932–1933: a collection of memoirs, speeches and essays prepared in 1983 in commemoration of the 50th anniversary of the Famine in Ukraine during 1932–33, , (Toronto: Ukrains'ke Pravoslavne Bratstvo Sv. Volodymyra, 1988), .

- Verbyts'kyi, M., Naibil'shyi zlochyn Kremlia: zaplianovanyi shtuchnyi holod v Ukraini 1932–1933 rokiv, (London, England: DOBRUS, 1952).

- Voropai, Oleksa, V deviatim kruzi, (London, England: Sum, 1953).

- Wheatcroft, Stephen G. (2000). "The Scale and Nature of Stalinist Repression and its Demographic Signicance: On Comments by Keep and Conquest" (PDF). Europe-Asia Studies. 52 (6): 1143–1159.

{{cite journal}}: C1 control character in|title=at position 71 (help) - Voropai, Oleksa, The Ninth Circle: In Commemoration of the Victims of the Famine of 1933, Olexa Woropay; edited with an introduction by James E. Mace, (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University, Ukrainian Studies Fund, 1983).

- Marco Carynnyk, Lubomyr Luciuk and Bohdan S Kordan, eds, The Foreign Office and the Famine: British Documents on Ukraine and the Great Famine of 1932–1933, foreword by Michael Marrus (Kingston: Limestone Press, 1988)

- Barbara Falk, Sowjetische Städte in der Hungersnot 1932/33. Staatliche Ernährungspolitik und städtisches Alltagsleben (= Beiträge zur Geschichte Osteuropas 38), Köln: Böhlau Verlag 2005 ISBN 3-412-10105-2

- Wasyl Hryshko, The Ukrainian Holocaust of 1933, (Toronto: 1983, Bahriany Foundation)

- R. Kusnierz, Ukraina w latach kolektywizacji i Wielkiego Glodu (1929–1933),Torun, 2005

- Leonard Leshuk, ed., Days of Famine, Nights of Terror: Firsthand Accounts of Soviet Collectivization, 1928–1934 (Kingston: Kashtan Press, 1995)

- Lubomyr Luciuk, ed., Not Worthy: Walter Duranty's Pulitzer Prize and The New York Times (Kingston: Kashtan Press, 2004)

- Rajca, Czesław (2005). Głód na Ukrainie. Lublin/Toronto: Werset. ISBN 83-60133-04-2.

- Bruski, Jan Jacek (2008). Hołodomor 1932–1933. Wielki Głód na Ukrainie w dokumentach polskiej dyplomacji i wywiadu (in Polish). Warszawa: Polski Instytut Spraw Międzynarodowych. ISBN 978-83-89607-56-0.

External links

- "Gareth Jones' international exposure of the Holodomor, plus many related background articles". Retrieved 5 July 2006.

- Template:Uk icon Famine in Ukraine 1932–1933 at the Central State Archive of Ukraine (photos, links)

- Stanislav Kulchytsky, Italian Research on the Holodomor, October 2005.

- Template:En icon Stanislav Kulchytsky, "Why did Stalin exterminate the Ukrainians? Comprehending the Holodomor. The position of Soviet historians" – Six part series from Den: Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5, Part 6; Kulchytsky on Holodomor 1–6

- Template:Ru icon/Template:Uk icon Valeriy Soldatenko, "A starved 1933: subjective thoughts on objective processes", Zerkalo Nedeli, 28 June – 4 July 2003. Available online in Russian and in Ukrainian.

- Template:Ru icon/Template:Uk icon Stanislav Kulchytsky's articles in Zerkalo Nedeli, Kiev, Ukraine"

- "How many of us perish in Holodomor on 1933", 23 November 2002 – 29 November 2002. Available online in Russian and in Ukrainian.

- "Reasons of the 1933 famine in Ukraine. Through the pages of one almost forgotten book" 16–22 August 2003. Available online in Russian and in Ukrainian.

- "Reasons of the 1933 famine in Ukraine-2", 4 October 2003 – 10 October 2003. Available online in Russian and in Ukrainian.

- "Demographic losses in Ukraine in the twentieth century", 2 October 2004 – 8 October 2004. Available online in Russian and in Ukrainian.

- "Holodomor-33: Why and how?" 25 November – 1 December. Available online in Russian and in Ukrainian.

- UKRAINIAN FAMINE Revelations from the Russian Archives at the Library of Congress

- Photos of Holodomor by Sergei Melnikoff

- The General Committee decided this afternoon not to recommend the inclusion of an item on the seventy-fifth anniversary of the Great Famine (Holodomor) of 1932–1933 in Ukraine.

- Case Study: The Great Ukrainian Famine of 1932–1933 By Nicolas Werth / CNRS – France

- Holomodor – Famine in Soviet Ukraine 1932–1933

- Famine in the Soviet Union 1929–1934 – collection of archive materials

- Holodomor: The Secret Holocaust in Ukraine – official site of the Security Service of Ukraine

- CBC program about the Great Hunger

- Caryle Murphy (1 October 1983). "Ukrainian Americans Commemorate Famine in Homeland 50 Years Ago". The Washington Post.

- People's war 1917–1932 by Kiev city organization "Memorial"

| Countries which officially recognise the Holodomor as genocide | ||

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

- There seems to be a disagreement between branches of Ukrainian government over the issue. See Holodomor genocide question#Genocide debate: Ukrainian position for details