This is an old revision of this page, as edited by 96.5.11.89 (talk) at 19:43, 17 September 2013 (→Biography). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 19:43, 17 September 2013 by 96.5.11.89 (talk) (→Biography)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) For other uses, see Alexander Fleming (disambiguation).

| Sir Alexander Fleming FRSE, FRS, FRCS(Eng) | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | (1881-08-06)6 August 1881 Lochfield, Ayrshire, Scotland |

| Died | 11 March 1955(1955-03-11) (aged 73) London, England |

| Nationality | Scottish |

| Citizenship | United Kingdom |

| Alma mater | Royal Polytechnic Institution St Mary's Hospital Medical School Imperial College London |

| Known for | Discovery of penicillin |

| Awards | Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine (1945) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Bacteriology, immunology |

| Signature | |

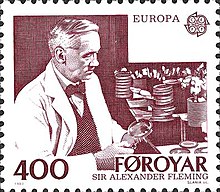

Sir Alexander Fleming, FRSE, FRS, FRCS(Eng) (6 August 1881 – 11 March 1955) was a Scottish biologist, pharmacologist and botanist. He wrote many articles on bacteriology, immunology, and chemotherapy. His best-known discoveries are the enzyme lysozyme in 1923 and the antibiotic substance penicillin from the mould Penicillium notatum in 1928, for which he shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1945 with Howard Florey and Ernst Boris Chain.

In 1999, Time magazine named Fleming one of the 100 Most Important People of the 20th Century, stating:

It was a discovery that would change the course of history. The active ingredient in that mould, which Fleming named penicillin, turned out to be an infection-fighting agent of enormous potency. When it was finally recognized for what it was, the most efficacious life-saving drug in the world, penicillin would alter forever the treatment of bacterial infections. By the middle of the century, Fleming's discovery had spawned a huge pharmaceutical industry, churning out synthetic penicillins that would conquer some of mankind's most ancient scourges, including syphilis, gangrene and tuberculosis.

Fleming's first wife, Sarah, died in 1949. Their only child, Robert Fleming, became a general medical practitioner. After Sarah's death, Fleming married Dr. Amalia Koutsouri-Vourekas, a Greek colleague at St. Mary's, on 9 April 1953; she died in 1986.

Death

In 1955, Fleming died at his home in London of a heart attack. He was buried in St Paul's Cathedral.

Honours, awards and achievements

His discovery of penicillin had changed the world of modern medicine by introducing the age of useful antibiotics; penicillin has saved, and is still saving, millions of people around the world.

The laboratory at St Mary's Hospital where Fleming discovered penicillin is home to the Fleming Museum, a popular London attraction. His alma mater, St Mary's Hospital Medical School, merged with Imperial College London in 1988. The Sir Alexander Fleming Building on the South Kensington campus was opened in 1998 and is now one of the main preclinical teaching sites of the Imperial College School of Medicine.

His other alma mater, the Royal Polytechnic Institution (now the University of Westminster) has named one of its student halls of residence Alexander Fleming House, which is near to Old Street.

- Fleming, Florey and Chain jointly received the Nobel Prize in Medicine in 1945. According to the rules of the Nobel committee a maximum of three people may share the prize. Fleming's Nobel Prize medal was acquired by the National Museums of Scotland in 1989 and is on display after the museum re-opened in 2011.

- Fleming was a member of the Pontifical Academy of Sciences.

- Fleming was awarded the Hunterian Professorship by the Royal College of Surgeons of England.

- Fleming was knighted, as a Knight Bachelor, by king George VI in 1944.

- He was made a Knight Grand Cross of the Order of Alfonso X the Wise in 1948.

- In 1999, Time Magazine named Fleming one of the 100 Most Important People of the 20th century.

- When 2000 was approaching, at least three large Swedish magazines ranked penicillin as the most important discovery of the millennium.

- In 2002, Fleming was named in the BBC's list of the 100 Greatest Britons following a nationwide vote.

- A statue of Alexander Fleming stands outside the main bullring in Madrid, Plaza de Toros de Las Ventas. It was erected by subscription from grateful matadors, as penicillin greatly reduced the number of deaths in the bullring.

- Flemingovo náměstí is a square named after Fleming in the university area of the Dejvice community in Prague.

- In mid-2009, Fleming was commemorated on a new series of banknotes issued by the Clydesdale Bank; his image appears on the new issue of £5 notes.

- 91006 Fleming, an asteroid in the Asteroid Belt, is named after Fleming.

See also

![]() Media related to Alexander Fleming at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Alexander Fleming at Wikimedia Commons

Bibliography

- The Life Of Sir Alexander Fleming, Jonathan Cape, 1959. Maurois, André.

- Nobel Lectures,the Physiology or Medicine 1942–1962, Elsevier Publishing Company, Amsterdam, 1964

- An Outline History of Medicine. London: Butterworths, 1985. Rhodes, Philip.

- The Cambridge Illustrated History of Medicine. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, 1996. Porter, Roy, ed.

- Penicillin Man: Alexander Fleming and the Antibiotic Revolution, Stroud, Sutton, 2004. Brown, Kevin.

- Alexander Fleming: The Man and the Myth, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1984. Macfarlane, Gwyn

- Fleming, Discoverer of Penicillin, Ludovici, Laurence J., 1952

References

- ^ "Alexander Fleming Biography". Les Prix Nobel. The Nobel Foundation. 1945. Retrieved 27 March 2011.

- ^ "Alexander Fleming – Time 100 People of the Century". Time. 29 March 1999.

It was a discovery that would change the course of history. The active ingredient in that mould, which Fleming named penicillin, turned out to be an infection-fighting agent of enormous potency. When it was finally recognized for what it was, the most efficacious life-saving drug in the world, penicillin would alter forever the treatment of bacterial infections. By the middle of the century, Fleming's discovery had spawned a huge pharmaceutical industry, churning out synthetic penicillins that would conquer some of mankind's most ancient scourges, including syphilis, gangrene and tuberculosis.

- "Alexander Fleming". FamousScientists.org. Retrieved 15 December 2011.

- "Sir Alexander Fleming – Biography". Nobelprize.org. Retrieved 25 October 2011.

- Roberts, Michael (2001). Biology (2, illustrated ed.). Nelson Thornes. p. 105. ISBN 0-7487-6238-8. Retrieved 4 March 2012.

Penicillin is just one of a very large number of drugs which today are used by doctors to treat people with diseases.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - "100,000 visitors in 6 days". National Museums Scotland. 3 August 2011. Retrieved 4 March 2012.

- "People of the century". P. 78. CBS News. Simon & Schuster, 1999

- "100 great Britons - A complete list". Daily Mail. Retrieved 3 August 2012

- ^ Edward Lewine (2007). "Death and the Sun: A Matador's Season in the Heart of Spain". p. 123. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2007

- "Banknote designs mark Homecoming". BBC News. 14 January 2008. Archived from the original on 25 January 2009. Retrieved 20 January 2009.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)

External links

- Alexander Fleming Biography

- Time, 29 March 1999, Bacteriologist Alexander Fleming

- Some places and memories related to Alexander Fleming

- Alexander Fleming

| Academic offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded byAlastair Sim | Rector of the University of Edinburgh 1951–1954 |

Succeeded bySydney Smith |

- Use dmy dates from April 2012

- 1881 births

- 1955 deaths

- 20th-century biologists

- People from East Ayrshire

- People educated at Kilmarnock Academy

- British Army personnel of World War I

- Alumni of Imperial College London

- Alumni of the University of Westminster

- Academics of Imperial College London

- Academics of the University of London

- Burials at St Paul's Cathedral

- Deaths in London

- Deaths from myocardial infarction

- Honorary Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh

- Fellows of the Royal Society

- Fellows of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh

- Fellows of the Royal College of Physicians

- Fellows of the Royal College of Surgeons

- Members of the Pontifical Academy of Sciences

- Knights Bachelor

- Nobel laureates in Physiology or Medicine

- Rectors of the University of Edinburgh

- Royal Army Medical Corps officers

- Scottish Science Hall of Fame

- Scottish bacteriologists

- Scottish biologists

- Scottish inventors

- Scottish knights

- 20th-century Scottish medical doctors

- Scottish microbiologists

- Scottish Nobel laureates

- Scottish pharmacologists

- Scottish soldiers

- Scottish surgeons