This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Hillman (talk | contribs) at 16:06, 10 June 2006 (/* Bell's thought experiment * / Yup, while rewriting I somehow dropped the "string" :-/). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 16:06, 10 June 2006 by Hillman (talk | contribs) (/* Bell's thought experiment * / Yup, while rewriting I somehow dropped the "string" :-/)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)In relativistic physics, Bell's spaceship paradox denotes any of a family of closely related thought experiments giving results which many students initially consider to be counterintuitive. They are also sometimes called spaceship and string paradoxes, and they are closely related to various thought experiments devised to study the behavior of an accelerated rod.

The best known example of a spaceship and string paradox was discussed by J. S. Bell in 1976, but a previous example had earlier been discussed by E. Dewan and M. Beran in 1959.

Bell's thought experiment

The setting for most spaceship and string paradoxes is Minkowski spacetime, the usual flat spacetime of special relativity.

In the simplest version of Bell's thought experiment, two spaceships are initially at rest in some Cartesian coordinate chart. That is, in the language of elementary special relativity, they are initially at rest in some inertial reference frame (Lorentz frame). Imagine that a string is stretched tight between the two spaceships. At time zero, the spaceships are suddenly "kicked" so that after time zero they are moving with constant velocity with respect to the original Lorentz frame. Question: does the string break?

Because this version of the "paradox" involves impulsive blows, a traditional source of confusion in interpreting spacetime diagrams, it is preferable to analyze the following slightly more general thought experiment:

Two spaceships, which are initially at rest in our Cartesian chart, are connected by a taut string. At time zero, the two spaceships start to accelerate with constant acceleration (as measured on board each ship). Question: does the string break?

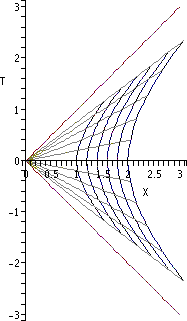

In a minor variant (see figure at right), both spaceships stop accelerating after a certain period of time previously agreed upon. The captain of each ship shuts off his engine after this time period has passed, as measured by an ideal clock carried on board his ship. This allows before and after comparisons in suitable inertial reference frames in the sense of elementary special relativity. In a suitable limit of this version of the second thought experiment, we can recover the first thought experiment, which was stated in terms of impulsive blows.

Elementary analysis

We study the outcome of the second thought experiment discussed above. We will use a Cartesian chart for Minkowski spacetime with the standard line element

The proper time parameterized world line of the first observer is given by

In the figure, the first spaceship begins to accelerate at event A, which has coordinates T = 0, X = α1, and stops accelerating at event A′, after time σ has elapsed by an ideal clock carried on board. During the acceleration phase, the path curvature (that is, the covariant derivative where is the unit tangent vector to the world line) has constant magnitude k, as measured on board the spaceship.

Likewise, the proper time parameterized world line of the second observer is given by

In the figure, the second spaceship begins to accelerate at event B, which has coordinates T = 0, X = α2, and stops accelerating at event B′, after time σ has elapsed by an ideal clock carried on board. After event B″, both spaceships can once again be treated as comoving inertial observers by the usual methods of elementary special relativity. We imagine that a string has been stretched between the two spaceships before the acceleration phase, and we wish to compare its length before and after the acceleration.

During the period , the two observers are separated by the constant distance . After the acceleration phase, their world lines are once again portions of straight lines (timelike geodesics) and we can easily compute the new distance using elementary geometry of Minkowski space.

Consider the line through event A′ which is orthogonal (in Minkowski geometry, not euclidean geometry!) to the tangent vector to the world line there. In the language of elementary special relativity, this line represents a "space of simultaneity". It is now a simple exercise in analytic geometry to find the intersection of this line at event B″ with the world line of the second observer. The new distance between the spaceships turns out to be

As Bell pointed out, unless the product k σ is very small, this increase in the distance between the two spaceships will break the string stretched between the two spaceships. See the figure above, where we have taken k = σ = 1, so that the length of the string has increased by about 1.5 (a factor which is more than sufficient to break most strings!).

Some might object that this conclusion would be unchanged if we replaced the hyperbolic arcs by any other timelike curve segments which have the appropriate endpoints (and the appropriate tangent vectors at these endpoints). In this case we cannot avoid analyzing the acceleration phase.

Bell observers

To assuage any remaining misgivings, we ought to verify that the string is indeed stretched continuously during the acceleration phase. This will be somewhat tricky, since it turns out (see Rindler coordinates) that even in flat spacetime, there are various distinct but operationally meaningful notions of distance which can be employed by accelerating observers. Fortunately, these all agree for very small distances. This suggests interpolating infinitely many new world lines between the two already considered. That is, we should introduce a family of ideal observers whose world lines form a timelike congruence. Then we can verify that during the acceleration phase, the distance between nearby bits of string increases continuously, without having to worry about competing notions of distance on larger scales.

We must find a unit timelike vector field whose integral curves are the world lines of form

Differentiating with respect to proper time, we obtain

Eliminating s yields

This gives a system of first order linear ordinary differential equations. Solving (or "integrating") this system gives back our family of hyperbolic curves. These are the integral curves of the vector field (first order linear partial differential operator)

At each event, this vector field is timelike and has unit length (using the line element given above). Therefore, this is the desired unit timelike vector field of tangent vectors to the world lines of our observers. We will call them Bell observers.

We can now obtain a frame field assigning an infinitesimal Lorentz frame to each event by augmenting this unit timelike vector field with three unit spacelike vector fields, such that all four vector fields are mutually orthogonal at each event. This is easily accomplished; we may take our frame field to be

(For simplicity, in this section we have let , but this is inessential to the discussion.)

Here is a timelike unit vector field, the tangent vector field to a congruence of timelike curves, while are spacelike unit vector fields, with all four being mutually orthogonal at each event. The congruence of timelike curves consists of parallel hyperbolas which represent the world lines of the Bell observers. In other words, this frame field assigns a infinitesimal Lorentz frame to the tangent space at each event, namely the frame representing the instantaneous state of motion of the Bell observer passing through that event.

We can now apply a standard method from the differential geometry of curves in Lorentzian manifolds, the so-called kinematic decomposition of a timelike congruence. A short computation shows that

confirming that each Bell observer feels a constant force after time zero, as measured in his own frame, and with all the Bell observers experiencing a force of the same magnitude. The components of the expansion tensor, evaluated with respect to this frame, are

The vorticity tensor vanishes, so the congruence of world lines of the Bell observers is hypersurface orthogonal. The orthogonal hyperslices are in fact locally isometric to ordinary euclidean space E even after time zero. These hyperslices have the form (two dimensions suppressed)

The nonzero component of the expansion tensor,

shows that--- contrary to the initial expectation of many students--- after time zero, the distance between nearby Bell observers is increasing. This component approaches k T as T decreases to zero from above, and approaches k as T grows without bound (see figure at right). That is, the expansion rate initially grows linearly and then approaches a constant value. Here T is the coordinate time of our Cartesian chart, but this can be easily re-expressed in terms of the proper time of one of our observers. In any case, using the dependence upon coordinate time rather than proper time does not affect the point of this computation: the expansion rate in the direction of acceleration approaches a positive constant. We have verified that the length of the string does grow continuously (until it breaks), and since the distance between each bit of matter in the string cannot grow without bound, we have confirmed that as Bell claimed the string must eventually break.

Rindler observers

Many readers will still be made uneasy by this claim. After all, in Newtonian mechanics, two bodies experiencing the same constant acceleration (same direction and magnitude) maintain a constant distance. Does our result imply that in relativistic physics, any accelerated object must eventually be torn apart? That would hardly make sense!

To study this issue, it is helpful to introduce another set of observers, called Rindler observers. Each of these observers also experience constant acceleration, but the value of this constant varies between the observers in just the right way to ensure that the Rindler observers do maintain constant distance to their nearest neighbors. (Actually, we get more than this: even distant Rindler observers maintain constant distance, according to any of several distinct but operationally significant notions of distance.)

The physical experience of Rindler observers may be described in terms of the frame field

Notice that this frame is only defined on the region , which is often called the Rindler wedge.

Computing the kinematic decomposition of the new congruence, we find that the acceleration vector of a Rindler observer is given by

Since each Rindler observer has a world line of form for some , each Rindler observer in fact has a constant acceleration (but different observers in the congruence might have different constant values associated with the magnitude of their acceleration). We stress that this is the acceleration as measured by the Rindler observers themselves, not static observers. Moreover, the expansion and vorticity tensors both vanish. Therefore the congruence of the world lines of Rindler observers is the closest we can come in relativistic physics to a rigidly accelerating congruence.

To better understand these new observers, it is helpful to change coordinates to a new chart, the Rindler chart, in which the world lines of the Rindler observers are represented as vertical lines; see Rindler coordinates. Note that frame fields, like their constituent vector fields, are geometric objects which can be represented in any coordinate chart covering at least part of their domain of definition. The methods of differential geometry yield information (such as the kinematic decomposition) which is largely independent of coordinate chart, but choosing a well adapted chart may still be useful. For example, in the Rindler chart, the acceleration of each observer is manifestly constant.

However, it is easier to see in our Cartesian chart that the world lines of the Rindler observers (with two dimensions suppressed) form a certain family of nested hyperbolas which are exactly analogous to a family of concentric circles in the euclidean plane E. Indeed, the fact that the world line of observer who experiences a constant acceleration is a hyperbola is simply the Minkowksi analog of the familiar fact that in euclidean geometry, a curve having constant path curvature along the curve is a circle. Furthermore, when we say that trailing Rindler observers have to acclerate harder than leading Rindler observers, we are saying that the world lines of trailing observers bend faster, per unit of arc length on their world line (that is, per unit of proper time) than do the world lines of leading observers, and this is analogous to the fact that in a family of concentric circles in the euclidean plane, inner circles must bend faster, per unit of arc length, than outer circles.

Once we see this, comparing the Rindler and Bell observers, it is easy to see why the expansion tensor of the congruence of world lines of Bell observers must be nonzero. (The euclidean analog of the Bell congruence consists of semicircles which all have the same radius and are all orthogonal at their midpoints to some line.)

If a rod is stretched between two such Rindler observers, "towed" by the leading observer, it will of course be under tension, and moreover after relaxation the rod should exhibit a nonzero tension gradient along its length. However, a detailed analysis of this phenomenon would require a material model. In the analysis above, note that if we replace "string: with "rod", we have tacitly assumed that a body force is applied to each element of the rod beginning at T=0. In particular, we have ignored that fact that if we intended rather to apply a force at just one point of the rod, the rest of the rod will take some time to respond. (The paper by Nikolić cited below offers some discussion of this issue.)

This raises a new issue: the simplest material model is suggested by Hooke's law. But is this compatible with relativistic kinematics? The answer would seem to be that strictly speaking it is not, since a spring modeled by Hooke's law responds instantaneously all along its length to a tug on one endpoint.

Dissident views

While the viewpoint presented in this article represents the mainstream viewpoint, from time to time papers do appear claiming that this viewpoint is incorrect. Some but not all of these authors feel that special relativity is itself logically untenable or incomplete. (See for example the papers by J. H. Field cited below.) Others pursue no quarrel with special relativity, but feel that the mathematics of the Lorentz transformation has been somehow misunderstood. In particular, some authors deny that in Bell's thought experiment, the string would break; some even deny that a string stretched between two Rindler observers would be under tension. The mainstream view is that these dissident viewpoints rest upon various misconceptions, often involving confusing distinct notions which happen to agree in simpler situations, such as various notions of "distance" which can be employed by accelerating observers.

See also

- Congruence (general relativity)

- Ehrenfest paradox

- Physical paradox

- Supplee's paradox

- Rindler coordinates

- Twin paradox

External links

- Michael Weiss, Bell's Spaceship Paradox (1995), USENET Relativity FAQ

- Austin Gleeson, Course Notes Chapter 13 See Section 4.3

References

The list of papers which discuss spaceship and string paradoxes or accelerated rods is too large to enumerate here, but we cite some representatives to assist students of the history of science.

A few early papers:

- Dewan, E.; and Beran, M. (1959). "Note on stress effects due to relativistic contraction". Am. J. Phys. 27: 517–518.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Nawrocki, P. J. "Stress Effects due to Relativistic Contraction". Am. J. Phys. 30: 771.

- Romain, J. E. (1963). "A Geometric approach to Relativistic paradoxes". Am. J. Phys. 31: 576–579.

The following book contains a reprint of Bell's 1976 paper discussing his version of the "paradox":

- Bell, J. S. (1987). Speakable and unspeakable in quantum mechanics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-52338-9.

Two recent papers expressing mainstream views:

- Nikolić, Hrvoje (1999). "Relativistic contraction of an accelerated rod". Am. J. Phys. 67: 1007. eprint version

- Matsuda, Takuya; & Kinoshita, Atsuya (2004). "A Paradox of Two Space Ships in Special Relativity". AAPPS Bulletin. February: ?.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) eprint version

Three recent papers expressing dissident views:

- Field, J. H. (2004). "On the Real and Apparent Positions of Moving Objects in Special Relativity: The Rockets-and-String and Pole-and-Barn Paradoxes Revisited and a New Paradox". arXiv:physics/0403094.

{{cite arXiv}}: Unknown parameter|version=ignored (help) - Field, J. H. (2005). "The Local Space-Time Lorentz Transformation: a New Formulation of Special Relativity Compatible with Translational Invariance". arXiv:physics/0501043.

{{cite arXiv}}: Unknown parameter|version=ignored (help) - Hsu, Jong-Ping; & Suzuki (2005). "Extended Lorentz Transformations for Accelerated Frames and the Solution of the "Two-Spaceship Paradox"". AAPPS Bulletin. October: ?.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) eprint version

where

where  is the unit tangent vector to the world line) has constant magnitude k, as measured on board the spaceship.

is the unit tangent vector to the world line) has constant magnitude k, as measured on board the spaceship.

, the two observers are separated by the constant distance

, the two observers are separated by the constant distance  . After the acceleration phase, their world lines are once again portions of straight lines (timelike geodesics) and we can easily compute the new distance using elementary geometry of Minkowski space.

. After the acceleration phase, their world lines are once again portions of straight lines (timelike geodesics) and we can easily compute the new distance using elementary geometry of Minkowski space.

, but this is inessential to the discussion.)

, but this is inessential to the discussion.)

is a

is a  are

are

, which is often called the Rindler wedge.

, which is often called the Rindler wedge.

for some

for some  , each Rindler observer in fact has a constant acceleration (but different observers in the congruence might have different constant values associated with the magnitude of their acceleration). We stress that this is the acceleration as measured by the Rindler observers themselves, not static observers. Moreover, the expansion and vorticity tensors both vanish. Therefore the congruence of the world lines of Rindler observers is the closest we can come in relativistic physics to a rigidly accelerating congruence.

, each Rindler observer in fact has a constant acceleration (but different observers in the congruence might have different constant values associated with the magnitude of their acceleration). We stress that this is the acceleration as measured by the Rindler observers themselves, not static observers. Moreover, the expansion and vorticity tensors both vanish. Therefore the congruence of the world lines of Rindler observers is the closest we can come in relativistic physics to a rigidly accelerating congruence.