This is an old revision of this page, as edited by EllenCT (talk | contribs) at 01:05, 7 January 2014 (→Changes in economic inequality: better paragraphs and positioning of navbar template: the weath section veers back into income by wealth levels). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 01:05, 7 January 2014 by EllenCT (talk | contribs) (→Changes in economic inequality: better paragraphs and positioning of navbar template: the weath section veers back into income by wealth levels)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)

The United States tax code in regard to income, capital gains, estate, and inheritance taxes, has undergone significant changes under both Republican and Democratic administrations and Congresses since 1964. Since the Johnson Administration, marginal income taxes have been reduced from 91% for the wealthiest Americans in 1964 to 35% for the same group by 2003 under the Bush Administration. Capital gains taxes have also decreased over the last several years, and have experienced a more punctuated evolution than income taxes as significant and frequent changes to these rates occurred from 1981 to 2011. Both estate and inheritance taxes have been steadily declining since the 1990s. Economic inequality in the United States has been steadily increasing since the 1980s as well and economists such as Paul Krugman, Joseph Stiglitz, and Peter Orszag, politicians like Barack Obama and Paul Ryan, and media entities have engaged in debates and accusations over the role of tax policy changes in perpetuating economic inequality.

A 2011 Congressional Research Service report stated, "Changes in capital gains and dividends were the largest contributor to the increase in the overall income inequality. Taxes were less progressive in 2006 than in 1996, and consequently, tax policy also contributed to the increase in income inequality between 1996 and 2006. But overall income inequality would likely have increased even in the absence of tax policy changes."

Much scholarly and popular literature exists on this topic with numerous works on both sides of the debate. The work of Emmanuel Saez, in particular, has shed more light on the role of American tax policy in aggregating wealth into the top 0.001% of households in recent years while classical arguments and research from conservative scholars such as Thomas Sowell of the Hoover Institute and Gary Becker of the University of Chicago maintain that education, globalization, and market forces, which operate on the premise of scarcity, are the root causes of income and overall economic inequality. The Revenue Act of 1964 and the "Bush Tax Cuts" are the bookends of the last fifty years of tax policy changes and coincide with the rising economic inequality in the United States both by socioeconomic class and race which makes them logical starting and end points for this scholarly and political debate.

Changes in economic inequality

Income inequality

Main article: Income inequality in the United StatesAmong economists and related experts, most agree that America's growing income inequality is "deeply worrying", unjust, a danger to democracy/social stability, or a sign of national decline. Yale professor Robert Shiller, who was among three Americans who won the Nobel prize for economics in 2013, said after receiving the award, "The most important problem that we are facing now today, I think, is rising inequality in the United States and elsewhere in the world."

Inequality in land and income ownership is negatively correlated with subsequent economic growth. A strong demand for redistribution will occur in societies where a large section of the population does not have access to the productive resources of the economy. Rational voters must internalize such issues. High unemployment rates have a significant negative effect when interacting with increases in inequality. Increasing inequality harms growth in countries with high levels of urbanization. High and persistent unemployment also has a negative effect on subsequent long-run economic growth. Unemployment may seriously harm growth because it is a waste of resources, because it generates redistributive pressures and distortions, because it depreciates existing human capital and deters its accumulation, because it drives people to poverty, because it results in liquidity constraints that limit labor mobility, and because it erodes individual self-esteem and promotes social dislocation, unrest and conflict. Policies to control unemployment and reduce its inequality-associated effects can strengthen long-run growth.

Gini coefficient

Main article: Gini coefficentThe Gini Coefficient, a statistical measurement of the inequality present in a nation's income distribution developed by Italian statistician and sociologist Corrado Gini, for the United States has increased over the last few decades. The closer the Gini Coefficient is to one, the closer its income distribution is to absolute inequality. In 2007, the United Nations approximated the United States' Gini Coefficient at 41% while the CIA Factbook placed the coefficient at 45%. The United States' Gini Coefficient was below 40% in 1964 and slightly decline through the 1970s. However, around 1981, the Gini Coefficient began to increase and rose steadily through the 2000s.

Wealth distribution

Main article: Wealth inequality in the United StatesWealth, in economic terms, is defined as the value of an individual's or household's total assets minus his or its total liabilities. The components of wealth include assets, both monetary and non-monetary, and income. Wealth is accrued over time by savings and investment. Levels of savings and investment are determined by an individual's or a household's consumption, the market real interest rate, and income. Individuals and households with higher incomes are more capable of saving and investing because they can set aside more of their disposable income to it while still optimizing their consumption functions. It is more difficult for lower-income individuals and households to save and invest because they need to use a higher percentage of their income for fixed and variable costs thus leaving them with a more limited amount of disposable income to optimize their consumption as compared to wealthy consumers. Accordingly, a natural wealth gap exists in any market as some workers earn higher wages and thus are able to divert more income towards savings and investment which build wealth.

The wealth gap in the United States is large and the vast majority of net worth and financial wealth is concentrated in a very small percentage of the population. Sociologist and University of California-Santa Cruz professor G. William Domhoff writes that "numerous studies show that the wealth distribution has been extremely concentrated throughout American history" and that "most Americans (high income or low income, female or male, young or old, Republican or Democrat) have no idea just how concentrated the wealth distribution actually is." In 2007, the top 1% of households owned 34.6% of all privately held wealth and the next 19% possessed 50.5% of all privately held wealth. Taken together, 20% of Americans controlled 85.1% of all privately held wealth in the country. In the same year, the top 1% of households also possessed 42.7% of all financial wealth and the top 19% owned 50.3% of all financial wealth in the country. Together, the top 20% of households owned 93% of the financial wealth in the United States. Financial wealth is defined as "net worth minus net equity in owner-occupied housing." In real money terms and not just percentage share of wealth, the wealth gap between the top 1% and the other quartiles of the population is immense. The average wealth of households in the top 1% of the population was $13,977,000 in 2009. This is fives times as large as the average household wealth for the next four percent (average household wealth of $2.7 million), fifteen times as large as the average household wealth for the next five percent (average household wealth of $908,000), and twenty-nine times the size of the average household wealth of the next ten percent of the population (average household wealth of $477,000) in the same year. Comparatively, the average household wealth of the lowest quartile was -$27,000 and the average household wealth of the second quartile (bottom 20-40th percentile of the population) was $5,000. The middle class, the middle quartile of the population, has an average household wealth level of $65,000.

| This article is part of a series on |

| Income in the United States of America |

|---|

|

| Topics |

| Lists by income |

|

|

According to the Congressional Budget Office, the real, or inflation-adjusted, after-tax earnings of the wealthiest one percent of Americans grew by 275% from 1979 to 2007. Simultaneously, the real, after-tax earnings of the bottom twenty percent of wage earnings in the United States grew 18%. The difference in the growth of real income of the top 1% and the bottom 20% of Americans was 257%. The average increase in real, after-tax income for all U.S. households during this time period was 62% which is slightly below the real, after-tax income growth rate of 65% experienced by the top 20% of wage earners, not accounting for the top 1%. Data aggregated and analyzed by Robert B. Reich, Thomas Piketty, and Emmanuel Saez and released in a New York Times article written by Bill Marsh shows that real wages for production and non-supervisory workers, which account for 82% of the U.S. workforce, increased by 100% from 1947 to 1979 but then increased by only 8% from 1979–2009. Their data also shows that the bottom fifth experience 122% growth rate in wages from 1947 to 1979 but then experienced a negative growth rate of 4% in their real wages from 1979–2009. The real wages of the top fifth rose by 99% and then 55% during the same periods, respectively. Average real hourly wages have also increased by a significantly larger rate for the top 20% than they have for the bottom 20%. Real family income for the bottom 20% increased by 7.4% from 1979 to 2009 while it increased by 49% for the top 20% and increased by 22.7% for the second top fifth of American families. As of 2007, the United Nations estimated the ratio of average income for the top 10% to the bottom 10% of Americans, via the Gini Coefficient, as 15.9:1. The ratio of average income for the top 20% to the bottom 20% in the same year and using the same index was 8.4:1. According to these UN statistics, the United States has the third highest disparity between the average income of the top 10% and 20% to the bottom 10% and bottom 20% of the population, respectively, of the OECD countries, or the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. Only Chile and Mexico have larger average income disparities between the top 10% and bottom 10% of the population with 26:1 and 23:1, respectively. Consequently, the United States has the fourth highest Gini Coefficient of the OECD countries at 40.8% which is lower than Chile's (52%), Mexico's (51%), and just lower than Turkey's (42%).

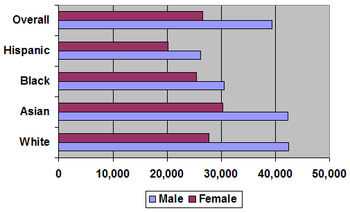

Inequality by race

Economic inequality in the United States varies significantly by race. Minorities, particularly African-Americans, generally earn lower incomes, own fewer assets, and pass on smaller inheritances to their children than white Americans earn, own, and pass on. The middle fifth of mean income for white Americans, for example, is approximately $50,350 while mean income for the middle fifth of African-Americans is approximately $14,950. Single black and Hispanic women have a median wealth of $100 and $120 respectively, while the median wealth for single white women is $41,500.

In 1999, 8% of white Americans were counted by the federal government as living in poverty due to their annual income. In the same year, 33% of African-Americans were income impoverished. From 1984 to 1999, the percentage of African-Americans living below the federal poverty line based on income grew while the Caucasian American income poverty level remained constant. An additional factor in the black-white income disparity distribution is the fact that the net worth of white Americans rises at a greater rate for every dollar they earn than net worth rises for every dollar earned by African-Americans. For every dollar that a white American earns, it increases his net worth by $3.25 as compared to only $2 for every dollar a black American earns. Several explanations exist for this gap: the average white American is more capable of affording financial services or purchasing financial assets that increase their wealth by a greater rate than the nominal interest rate on money than African-Americans are; white Americans have a higher rate of savings in general than African-Americans so their net worth is greater over time; white Americans may have access to more productive mechanisms through which they consume than African-Americans thus they can save more dollars for investment which could explain their greater marginal effect of income on wealth than the marginal effect African-Americans obtain.

Asset poverty is also more prevalent among black Americans than it is among white Americans. 55% of African-American households were considered asset poor in 1999 versus 25% of white Americans for the same year. Asset poverty, in 1999, was defined as owning less than $4,175 worth of non-monetary assets. Minorities are also far more likely than whites to live or have lived in poverty, live in impoverished neighborhoods, and experience greater incidents, collectively, of crime, domestic abuse, labor exploitation, teenage pregnancy, divorce, and single-parent homes. 74% of white American children have never lived below the poverty line while only 24% of African-American children have never lived below the poverty line. 18% of African-American children have experienced living in poverty for five to nine years and 24% of African-American children have experienced poverty for ten to fourteen years. 5% of Caucasian American children have lived in poverty for five to nine years and approximately 1% of all white American children have or do live in a state of poverty for ten to fourteen years. 90% of long-term poor Americans are black and 60% of long-term poor grew up in female-headed households which are disproportionately black. African-Americans are more likely to live in or around poverty and to grow-up in single-parent, female-led homes than any other demographic in the country. For example, 24% of blacks and 15% of Hispanics live in extreme poverty neighborhoods as compared to 3% of whites Americans who live in such neighborhoods. A neighborhood is designated as being in extreme poverty if 40% of its residents live below the poverty line. Minorities, especially African-Americans, account for larger numbers of citizens living in distressed neighborhoods, or neighborhoods with higher than average rates of joblessness, female-headed households, school dropouts, welfare-recipients, and poverty, than whites. Less than 5% of white Americans live in distressed neighborhoods as compared to 30% of blacks and 13% of Hispanics. Not only do minorities account for a larger total number of individuals living in distressed neighborhoods, but they also have the fastest growth rate of individuals living in these neighborhoods. In 1970, 7% of African-Americans and 2% of Hispanic Americans lived in distressed neighborhoods. These numbers increased to 30% and 13%, respectively, by 1990, and have continued to grow. Minorities are also less capable of being socially mobile than White Americans. 72% of nonwhites who were in the bottom quartile of income in 1968 were still in the bottom quartile in 1990 as compared to only 46% of whites who failed to rise from the bottom income quartile over that same 22 year span.

Relationship with tax code changes

U.S. Tax Policy changes since 1964 perpetuating inequality

Compression and divergence

Princeton economics professor, Nobel laureate, and John Bates Clarke Award winner Paul Krugman argues that politics not economic conditions have made income inequality in the United States "unique" and to a degree that "other advanced countries have not seen." According to Krugman, government action can either compress or widen income inequality through tax policy and other redistributive or transfer policies. Krugman illustrates this point by describing "The Great Compression" and "The Great Divergence." He states that the end of the Great Depression to the end of World War II, from 1939–1946, saw a rapid narrowing of the spread of the income distribution in America which effectively created the middle class. Krugman calls this economic time period "The Great Compression" because the income distribution was compressed. He attributes this phenomenon to intrinsically equalizing economic policy such as increased tax rates on the wealthy, higher corporate tax rates, a pro-union organizing environment, minimum wage, Social Security, unemployment insurance, and "extensive government controls on the economy that were used in a way that tended to equalize incomes." This "artificial" created middle class endured due to the creation of middle class institutions, norms, and expectations that promoted income equality. Krugman believes this period ends in 1980, which he points out as being "interesting" because it was when "Reagan came to the White House." From 1980 to the present, Krugman believes income inequality was uniquely shaped by the political environment and not the global economic environment. For example, the U.S. and Canada both had approximately 30% of its workers in unions during the 1960s. However, by 2010, around 25% of Canadian workers are still unionized while only 11% of American workers are unionized. Krugman blames Reagan for this rapid decline in unionization because he "declared open season on unions" while the global market clearly made room for unions as Canada's high union rate proves. Contrary to the arguments made by Chicago economists such as Gary Becker, Krugman points out that while the wealth gap between the college educated and non-college educated continues to grow, the largest rise in income inequality is between the well-educated-college graduates and college graduates-and not between college graduates and non-college graduates. The average high school teacher, according to Krugman, has a post-graduate degree which is a comparable level of education to a hedge fund manager whose income is multiples of the average high school teacher. In 2006, the "highest paid hedge fund manager in the United States made an amount equal to the salaries of all 80,000 New York City school teachers for the next three years." Accordingly, Krugman believes that education and a shifting global market are not the sole causes of increased income inequalities since the 1980s but rather that politics and the implementation of conservative ideology has aggregated wealth into the hands of the rich. Some of these political policies include the Reagan tax cuts in 1981 and 1986.

Nobel laureate Joseph Stiglitz asserts in a Vanity Fair article published in May 2011 entitled "Of the 1%, by the 1%, for the 1%" that "preferential tax treatment for special interests" has helped increase income inequality in the United States as well as reduced the efficiency of the market. He specifically points to the reduction in capital gains over the last few years, which are "how the rich receive a large portion of their income," as giving the wealthy a "free ride." Stiglitz criticizes the "marginal productivity theory" saying that the largest gains in wages are going toward less than worthy, in his mind, occupations such as finance whose effects have been "massively negative." Accordingly, if income inequality is predominately explained by rising marginal productivity of the educated then why are financiers, who are responsible for bringing the U.S. economy "to the brink of ruin."

Thomas Piketty and Emmanuel Saez wrote in their work "Income Inequality in the United States,1913–1998" that "top income and wages shares(in the United States) display a U-shaped pattern over the century" and "that the large shocks that capital owners experienced during the Great Depression and World War II have had a permanent effect on top capital incomes...that steep progressive income and estate taxation may have prevented large fortunes from recovery form the shocks." Saez and Piketty argue that the "working rich" are now at the top of the income ladder in the United States and their wealth far out-paces the rest of the country. Piketty and Saez plotted the percentage share of total income accrued by the top 1%, top 5%, and the top 10% of wage earners in the United States from 1913-2008. According to their data, the top 1% controlled 10% of the total income while the top 5% owned approximately 13% and the top 10% possessed around 12% of total income. By 1984, the percentage of total income owned by the top 1% rose from 10% to 16% while income shares of the top 5% and top 10% controlled 13.5% and 12%, respectively. The growth in income for the top 1% then skyrocketed up to 22% by 1998 while the income growth rates for the top 5% and top 10% remained constant (15% total share of income and 12% total share of income, respectively). The percentage share of total income owned by the top 1% fell to 16% during the post-911 recession but then re-rose to its 1998 level by 2008. In 2008, the wealth gap in terms of percentage of total income in the United States between the top 1% and 5% was 7% and the gap between the top 1% and top 10% was 9%. This is a 11% reversal from the respective percentage shares of income held by these groups in 1963. Income inequality clearly accelerated beginning in the 1980s.

Larry Bartels, a Princeton political scientist and the author of Unequal Democracy, argues that federal tax policy since 1964 and starting even before that has increased economic inequality in the United States. He states that the real income growth rate for low and middle class workers is significantly smaller under Republican administrations than it is under Democratic administrations while the real income growth rate for the upper class is much larger under Republican administrations than it is for Democratic administrations. He finds that from 1948 to 2005, pre-tax real income growth for the bottom 20% grew by 1.42% while pre-tax real income growth for the top 20% grew by 2%. Under the Democratic administrations in this time period, (Truman, Kennedy, Johnson, Carter, and Clinton) the pre-tax real income growth rate for the bottom 20% was 2.64% while the pre-tax real income growth rate for the top 20% was 2.12%. During the Republican administrations of this time period (Eisenhower, Nixon, Ford, Reagan, Bush, and Bush), the pre-tax real income growth rate was 0.43% for the bottom 20% and 1.90% for the top 20%. The disparity under Democratic presidents in this time period between the top and bottom 20% pre-tax real income growth rate was -0.52% while the disparity under Republican presidents was 1.47%. It is also worth noting that the pre-tax real income growth rate for the 40%, 60%, and 80% of population was higher under the Democratic administrations than it was under the Republican administrations in this time period. The United States was more equal and growing wealthier, based on income, under Democratic Presidents from 1948-2005 than it was under Republican Presidents in the same time period. Additionally, Bartels believes that the reduction and the temporary repeal of the estate tax also increased income inequality by benefiting almost exclusively the wealthiest in America.

According to a working paper released by the Society for the Study of Economic Inequality entitled "Tax policy and income inequality in the U.S.,1978—2009: A decomposition approach," tax policy can either exacerbate or curtail economic inequality. This article argues that tax policy reforms passed under Republican administrations since 1979 have increased economic inequality while Democratic administrations during the same time period have reduced economic inequality. The net vector movement of tax reforms on economic inequality since 1979 is essentially zero as the opposing policies neutralized each other.

A New York Times article argues the inequality of the past three decades came especially from tax cuts on capital gains. In addition for rates for all taxpayers being at 50 year lows, it claims that the last major overhaul of the tax code, signed by President Ronald Reagan in 1986, set tax rates on capital gains at the same level as the rates on ordinary income like salaries and wages, with both topping out at 28 percent. That link was uncoupled by his successor, President George Bush, and the rates on capital gains were reduced by President Bill Clinton. President George W. Bush then lowered the rates on capital gains and dividends to a high of 15 percent — less than half the 35 percent top rate on ordinary income. While rates for all American taxpayers have fallen to near 50-year lows, the wealthy have reaped the most savings from the changes because they derive a larger proportion of their income from investments. President Ronald Reagan's 1981 cut in the top regular tax rate on unearned income reduced the maximum capital gains rate to only 20%--its lowest level since the Hoover administration. President Bush's veto of tax harmonization has also been attributed to rising inequality, as this would have shut down offshore tax havens.

From the White House's own analysis, the tax burden for those making greater than $250,000 fell considerably during the late 1980s, 1990s and 2000s (decade), from an effective tax of 35 percent in 1980, down to under 30% from the late 1980s to present. For those making over $2 million it fell from 50% in 1960 to around 30% today.

Effective tax rates

Timothy Noah, senior editor of the New Republic, argues that while Ronald Reagan made massive reductions in the nominal marginal income tax rates with his Tax Reform Act of 1986, this reform did not make a similarly massive reduction in the effective tax rate on marginal incomes. Noah writes in his ten part series entitled "The Great Divergence," that "in 1979, the effective tax rate on the top 0.01 percent was 42.9 percent, according to the Congressional Budget Office, but by Reagan's last year in office it was 32.2%." This effective rate held steadily until the first few years of the Clinton presidency when it increased to a peak high of 41%. However, it fell back down to the low 30s by his second term in the White House. This percentage reduction in the effective marginal income tax rate for the wealthiest Americans, 9%, is not a very large decrease in their tax burden, according to Noah, especially in comparison to the 20% drop in nominal rates from 1980 to 1981 and the 15% drop in nominal rates from 1986 to 1987. In addition to this small reduction on the income taxes of the wealthiest tax payers in America, Noah discovered that the effective income tax burden for the bottom 20% of wage earners was 8% in 1979 and dropped to 6.4% under the Clinton Administration. This effective rate further dropped under the George W. Bush Administration. Under Bush, the rate decreased from 6.4% to 4.3%. Reductions in the effective income tax burden on the poor coinciding with modest reductions in the effective income tax rate on the wealthiest 0.01% of tax payers could not have been the driving cause of increased income inequality that began in the 1980s. These figures are similar to an analysis of effective federal tax rates from 1979-2005 by the Congressional Budget Office. The figures show a decrease in the total effective tax rate from 37.0% in 1979 to 29% in 1989. The effective individual income tax rate dropped from 21.8% to only 19.9% in 1989.

Other factors

Infrastructure spending

Infrastructure spending is considered government investment because it will usually save money in the long run, and thereby reduce the net present value of government liabilities. Spending on physical infrastructure in the U.S. returns an average of about $1.97 for each $1.00 spent on nonresidential construction because it is almost always less expensive to maintain than repair or replace once it has become unusable.

Education and globalization

Public subsidy of college tuition will increase the net present value of income tax receipts because college educated taxpayers earn much more than those without college education.

Nobel laureate and John Bates Clarke Award Winner Gary Becker, professor economics and sociology at the University of Chicago and a senior fellow of the Hoover Institute, argues that the root cause of income inequality is differing levels of educational attainment. Consequently, the "rise in returns on investments in human capital is beneficial and desirable" to society, according to Becker because it increases productivity and standards of living. Becker points to the widening gap in earnings between the college and graduate school educated and those who did not go to college. In 1980, the average income of a college graduate was 30% larger than the average income of a high school graduate. The average income of a worker with a graduate degree was 50% larger than the average income of a high school-educated worker. By 2007, the average college graduate earned 70% more than a non-college graduate and the income premium of a graduate degree was over 100%. Becker argues that while education is widening the income gap, it is simultaneously creating more opportunities for the poor and for marginalized ethnic and gender groups. According to him, the income growth with respect to education for women parallels the growth for men and the same is true between blacks and whites. Globalization, which has been spurred on by growing educational attainment, has also helped increase income and overall wealth inequality. Rapidly growing globalization during the 1980s due to the rise of emerging markets and increased demand for complex products increased the demand for high-skilled, highly educated workers because their marginal product of labor increased while the marginal product of labor for unskilled workers remained the same. This occurred because high-skilled workers were needed to operate new technology and to perform services that could not be done by low-skilled, low-educated laborers. Accordingly, the real wage of college graduates increased and declined for low-skill laborers which widened the wealth gap. Additionally, globalization combined with increased educational opportunities shifted the economy away from a manufacturing base to a finance and services-dominated market. Becker argues that this rise in income inequality is only a temporary and necessary transitory stage as the ever rising rates of return on investment in education will simply serve to raise living standards, productivity, and human capital across the board as more and more people become college and post-undergraduate level educated. He even argues that income inequality could reverse itself as more and more Americans get college degrees.

Healthcare spending

Main article: Healthcare reform in the United StatesPreventative health care expenditures can save several hundreds of billions of dollars per year in the U.S., because for example cancer patients are more likely to be diagnosed at Stage I where curative treatment is typically a few outpatient visits, instead of at Stage III or later in an emergency room where treatment can involve years of hospitalization and is often terminal.

Overview of tax changes from 1964 to 2010

Since 1964, the U.S. income tax has become significantly less progressive. Other taxes such as capital gains, estate, and inheritance taxes have also become less progressive over the last several decades. Most of the reductions to these taxes, however, have occurred in the last twenty years. A tax code is considered progressive if the tax rate rises as the value of taxable wealth rises. A progressive tax code is believed to mitigate the effects of recessions by taking a smaller percentage of income from lower-income consumers than from other consumers in the economy so they can spend more of their disposable income on consumption and thus restore equilibrium. This is known as an automatic stabilizer as it does not need Congressional action such as legislation. It also mitigates inflation by taking more money from the wealthiest consumers so their large level of consumption doesn't create demand-driven inflation. The Revenue Act of 1964 was the first bill of the Post-World War II era to reduce marginal income tax rates. This reform, which was proposed under John F. Kennedy but passed under Lyndon Johnson, reduced the top marginal income (annual income of $2.9 million+ adjusted for inflation) tax rate from 91% to 70% for annual incomes of $1.4 million+. It was the first tax legislation to reduce the top end of the marginal income tax rate distribution since 1924. The top marginal income tax rate had been 91% since 1946 and hadn’t been below 70% since 1936. The “Bush Tax Cuts,” which are the popularly known names of the Economic Growth and Tax Relief Reconciliation Act of 2001 and the Jobs and Growth Tax Relief Reconciliation Act of 2003 passed during President George W. Bush’s first term, reduced the top marginal income tax rate from 38.6% (annual income at $382,967+ adjusted for inflation) to 35%. These rates were continued under the Obama Administration and will extend through 2013. The number of income tax brackets declined during this time period as well but several years, particularly after 1992, saw an increase in the number of income tax brackets. In 1964, there were 26 income tax brackets. The number of brackets was reduced to 16 by 1981 and then collapsed into 13 brackets after passage of the Economic Recovery Tax Act of 1981. Five years later, the 13 income tax brackets were collapsed into five under the Reagan Administration. By the end of the Bush 41 Administration in 1992, the number of income tax brackets had reached an all-time low of three but President Bill Clinton oversaw a reconfiguration of the brackets that increased the number to five in 1993. The current number of income tax brackets, as of 2011, is six which is the number of brackets configured under President George W. Bush.

The following table shows the marginal income tax rates for married individuals filling-jointly from 1964-2010, adjusted for inflation. This table demonstrates the trend of declining top marginal income tax rates since 1964. With the brief exception of the 1992 to 1994 fiscal years, the table shows a sharp decline in marginal income tax rates starting in 1964 and continuing through 2003.

| Year | $10,001 | $20,001 | $60,001 | $100,001 | $250,001 | $500,001 | $1,000,000 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1964 | 23% | 34% | 56% | 66% | 76% | 77% | 77% |

| 1966 - 1976 | 22% | 32% | 53% | 62% | 70% | ||

| 1980 | 18% | 24% | 54% | 59% | 70% | ||

| 1982 | 16% | 22% | 49% | 50% | 50% | ||

| 1984 | 14% | 18% | 42% | 45% | 50% | ||

| 1986 | 14% | 18% | 38% | 45% | 50% | ||

| 1988 | 15% | 15% | 28% | 28% | 28% | ||

| 1990 | 15% | 15% | 28% | 28% | 28% | ||

| 1992 | 15% | 15% | 28% | 28% | 31% | ||

| 1994 | 15% | 15% | 28% | 31% | 39.6% | ||

| 1996 | 15% | 15% | 28% | 31% | 36% | ||

| 1998 | 15% | 15% | 28% | 28% | 36% | ||

| 2000 | 15% | 15% | 28% | 28% | 36% | ||

| 2002 | 10% | 15% | 27% | 27% | 35% | ||

| 2004 | 10% | 15% | 25% | 25% | 33% | ||

| 2006 | 10% | 15% | 15% | 25% | 33% | ||

| 2008 | 10% | 15% | 15% | 25% | 33% | ||

| 2010 | 10% | 15% | 15% | 25% | 33% |

Source: Tax Foundation

Main article: Capital gains tax in the United StatesCapital gains are profits from investments in capital assets such as bonds, stocks, and real estate. These gains are taxed, for individuals, as ordinary income when held for less than one year which means that they have the same marginal tax rate as the marginal income tax rate of their recipient. This is known as the capital gains tax rate on a short-term capital gains. Accordingly, the capital gains tax rate for short-term capital gains paid by an individual is equal to the marginal income tax rate of that individual. The tax rate then decreases once the capital gain becomes a long-term capital gain, or is held for 1 year or more. In 1964, the effective capital gains tax rate was 25%. This means that the actual tax percentage of all capital gains realized in the U.S. in 1964 was 25% as opposed to the nominal capital gains tax rate, or the percentage that would have been collected by the government prior to deductions and evasions. This effective rate held constant until a small rise in 1968 up to 26.9% and then began steadily increasing until it peaked at 39.875% in 1978. This top rate then fell to 28% in 1979 and further dropped to 20% in 1982. This top capital gains rate held until 1986 when the Tax Reform Act of 1986 re-raised it to 28% and 33% for all individuals subject to phase-outs. The Tax Reform Act of 1986 shifted capital gains to income for the first time thus establishing equal short-term capital gains taxes and marginal income tax rates. The top rate of 28%, not taking into account taxpayers under the stipulations of a phase-out, remained until 1997, despite increases in marginal income tax rates, when it was lowered to 28%. Starting in May 1997, however, long-term capital gains were divided into multiple subgroups based on the duration of time investors held them. Each new subgroup had a different tax rate. This effectively reduced the top capital gains tax rate on a long-term capital good held for over 1 year from 28% to 20%. These multiple subgroups were reorganized into less than one year, one to five years, and five years or more and were in place from 1998 to 2003. In 2003, the divisions reverted to the less than one year and more than one year categories until 2011 when they reverted to the three divisions first implemented in 1998. This rate, 20%, remained until 2003 when it was further reduced to 15%. The 15% long-term capital gains tax rate was then changed back to its 1997 rate of 20% in 2011.

Capital gains taxes for the bottom two and top two income tax brackets have changed significantly since the late 1980s. The short-term and long-term capital gains tax rates for the bottom two tax rates, 15% and 28%, respectively, were equal to those tax payers' marginal income tax rates from 1988 until 1997. In 1997, the capital gains tax rates for the bottom two income tax brackets were reduced to 10% and 20% for the 15% and 28% income tax brackets, respectively. These rates remained until 2001.

President Bush made additional changes to the capital gains tax rates for the bottom two income tax brackets in 2001, which were lowered from 15% and 28% to 10% and 15%, respectively, by lowering the tax on long-term capital gains held for more than five years from 10% to 8%. He also reduced the tax on short-term capital gains from 28% to 15% for the 15% tax bracket as well as lowered the tax on long-term capital goods from 20% to 10%. In 2003, the capital gains tax on long-term capital goods decreased from 10% to 5% for both of the bottom two tax brackets (10% and 15%). In 2008, these same rates were dropped to 0% but were restored to the 2003 rates in 2011 under President Obama via the extension of the Bush Tax Cuts.

Overall, capital gains tax rates decreased significantly for both the bottom two and the top two income tax brackets. The top two income tax brackets have had a net decrease in their long-term capital gains tax rates of 13% since 1988, while the lowest two income tax brackets' long-term capital gains tax rates have changed by 10% and 13%, respectively, in that time. The difference between income and long-term capital gains taxes for the top two income tax brackets (5% in 1988 and 18% and 20%, respectively, in 2011), however, is larger than the difference between the income and long-term capital gains tax rates for the bottom two income tax brackets (0% in 1988 and 5% and 10%, respectively, in 2011).

The inheritance tax, which is also known as the "gift tax", has been altered in the Post-World War II era as well. First established in 1932 as a means to raise tax revenue from the wealthiest Americans, the inheritance tax was put at a nominal rate of 25% points lower than the estate tax which meant its effective rate was 18.7%. Its exemption, up to $50,000, was the same as the estate tax exemption.Under current law, individuals can give gifts of up to $13,000 without incurring a tax and couples can poll their gift together to give a gift of up to $26,000 a year without incurring a tax. The lifetime gift tax exemption is $5 million which is the same amount as the estate tax exemption. These two exemptions are directly tied to each other as the amount exempted from one reduces the amount that can be exempted from the other at a 1:1 ratio. The inheritance/gift tax generally affects a very small percentage of the population as most citizens do not inherit anything from their deceased relatives in any given year. In 2000, the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland published a report that found that 1.6% of Americans received an inheritance of $100,000 or more and an additional 1.1% received an inheritance worth $50,000 to $100,000 while the other 91.9% of Americans did not receive an inheritance. A 2010 report conducted by Citizens for Tax Justice found that only 0.6% of the population would pass on an inheritance in the event of death in that fiscal year. Accordingly, data shows that inheritance taxes are a tax almost exclusively on the wealthy. In 1986, Congress enacted legislation to prevent trust funds of wealthy individuals from skipping a generation before taxes had to be paid on the inheritance.

Estate taxes, while affecting more taxpayers than inheritance taxes, do not affect many Americans and are also considered to be a tax aimed at the wealthy. In 2007, all of the state governments combined collected only $22 billion in tax receipts from estate taxes and these taxes affected less than 5% of the population including less than 1% of citizens in every state. In 2004, the average tax burden of the federal estate tax was 0% for the bottom 80% of the population by household. The average tax burden of the estate tax for the top 20% was $1,362. The table below gives a general impression of the spread of estate taxes by income. A certain dollar amount of every estate can be exempted from tax, however. For example, if the government allows an exemption of up to $2 million on an estate then the tax on a $4 million estate would only be paid on $2 million worth of that estate, not all $4 million. This reduces the effective estate tax rate. In 2001, the "exclusion" amount on estates was $675,000 and the top tax rate was 55%. The exclusion amount steadily increased to $3.5 million by 2009 while the tax rate dropped to 45% when it was temporarily repealed in 2010. The estate tax was reinstated in 2011 with a further increased cap of $5 million for individuals and $10 million for couples filing jointly and a reduced rate of 35%. The "step-up basis" of estate tax law allows a recipient of an estate or portion of an estate to have a tax basis in the property equal to the market value of the property.This enables recipients of an estate to sell it at market value without having paid any tax on it. According to the Congressional Budget Office, this exemption costs the federal government $715 billion a year.

Source: Estate Tax in the United States, Misplaced Pages

| Lower Limit | Upper Limit | Initial Taxation | Further Taxation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | $10,000 | $0 | 18% of the amount |

| $10,000 | $20,000 | $1,800 | 20% of the excess |

| $20,000 | $40,000 | $3,800 | 22% of the excess |

| $40,000 | $60,000 | $8,200 | 24% of the excess |

| $60,000 | $80,000 | $13,000 | 26% of the excess |

| $80,000 | $100,000 | $18,200 | 28% of the excess |

| $100,000 | $150,000 | $23,800 | 30% of the excess |

| $150,000 | $250,000 | $38,800 | 32% of the excess |

| $250,000 | $500,000 | $70,800 | 34% of the excess |

| $500,000 | and over | $155,800 | 35% of the excess |

Revenue Act of 1964

Main article: Revenue Act of 1964According to the Office of Tax Analysis of the United States Department of the Treasury, the Revenue Act of 1964 achieved the following major changes to the U.S. tax code: reduced top marginal rate of married individuals filling-jointly from 91% to 70% and reduced the corporate tax rate from 52% to 48%. The following table shows each marginal income tax rate from 1963 to 1965, adjusted for inflation.

| Year | $0 – $29,331 | $29,331 – $58,661 | $58,661 – $87,992 | $87,992 – $117,323 | $117,323 – $146,653 | $146,653 – $175,984 | $175,984 – $205,315 | $205,315 – $234,645 | $234,645 – $263,976 | $263,976 – $293,307 | $293,307 – $322,637 | $322,637 – $381,299 | $381,299 – $469,291 | $469,291 – $557,283 | $557,283 – $645,275 | $645,275 – $733,267 | $733,267 – $879,920 | $879,920 – $1,026,573 | $1,026,573 – $1,173,227 | $1,173,227 – $1,319,880 | $1,319,880 – $1,466,533 | $1,466,533 – $2,199,800 | $2,199,800 – $2,933,067 | $2,933,067+ | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1963 | 20% | 22% | 26% | 30% | 34% | 38% | 43% | 47% | 50% | 53% | 56% | 59% | 62% | 65% | 69% | 72% | 75% | 78% | 81% | 84% | 87% | 89% | 90% | 91% | ||

| Year | $0 – $7,238 | $7,238 – $14,476 | $14,476 – $21,714 | $21,714 – $28,952 | $28,952 – $57,904 | $57,904 – $86,857 | $86,857 – $115,809 | $115,809 – $144,761 | $144,761 – $173,713 | $173,713 – $202,665 | $202,665 – $231,618 | $231,618 – $260,570 | $260,570 – $289,522 | $289,522 – $318,474 | $318,474 – $376,379 | $376,379 – $463,235 | $463,235 – $550,092 | $550,092 – $636,949 | $636,949 – $723,805 | $723,805 – $868,566 | $868,566 – $1,013,327 | $1,013,327 – $1,158,088 | $1,158,088 – $1,302,849 | $1,302,849 – $1,447,610 | $1,447,610 – $2,895,221 | $2,895,221+ |

| 1964 | 16% | 16.5% | 17.5% | 18% | 20% | 23.5% | 27% | 30.5% | 34% | 37.5% | 41% | 44% | 47.5% | 50.5% | 53.5% | 56% | 58.5% | 61% | 63.5% | 66% | 68.5% | 71% | 73.5% | 75% | 76.5% | 77% |

| Year | $0 – $7,123 | $7,123 – $14,246 | $14,246 – $21,369 | $21,369 – $28,493 | $28,493 – $56,985 | $56,985 – $85,478 | $85,478 – $113,971 | $113,971 – $142,463 | $142,463 – $170,956 | $170,956 – $199,449 | $199,449 – $227,941 | $227,941 – $256,434 | $256,434 – $284,927 | $284,927 – $313,419 | $313,419 – $370,404 | $370,404 – $455,882 | $455,882 – $541,360 | $541,360 – $626,838 | $626,838 – $712,316 | $712,316 – $854,780 | $854,780 – $997,243 | $997,243 – $1,139,706 | $1,139,706 – $1,282,169 | $1,282,169 – $1,424,633 | $1,424,633+ | |

| 1965 | 14% | 15% | 16% | 17% | 19% | 22% | 25% | 28% | 32% | 36% | 39% | 42% | 45% | 48% | 50% | 53% | 55% | 58% | 60% | 62% | 64% | 66% | 68% | 69% | 70% |

Source: Tax Foundation

Economic Recovery Tax Act of 1981

Main article: Economic Recovery Tax Act of 1981According to the Office of Tax Analysis of the United States Department of the Treasury, the Economic Recovery Tax Act changed the tax code in the following ways: phased-in a 23% cut in individual tax rates over three years; reduced the top marginal income tax rate of married individuals filing-jointly from 70% to 50%; established a 10% exclusion on income for two-earner married couples ($3,000 cap); and phased-in an increase in the estate tax exemption from $175,625 to $600,000 in 1987. The following table shows each marginal income tax rate for 1981 and 1982, adjusted for inflation.

| Year | $0 – $8,393 | $8,393 – $13,576 | $13,576 – $18,760 | $18,760 – $29,374 | $29,374 – $39,495 | $39,495 – $49,862 | $49,862 – $60,723 | $60,723 – $73,806 | $73,806 – $86,888 | $86,888 – $113,054 | $113,054 – $148,105 | $148,105 – $211,297 | $211,297 – $270,045 | $270,045 – $400,872 | $400,872 – $531,698 | $531,698+ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1981 | 0% | 14% | 16% | 18% | 21% | 24% | 28% | 32% | 37% | 43% | 49% | 54% | 59% | 64% | 68% | 70% |

| Year | $0 – $8,393 | $7,906 – $12,788 | $12,788 – $17,671 | $17,671 – $27,670 | $27,670 – $37,203 | $37,203 – $46,969 | $46,969 – $57,199 | $57,199 – $69,523 | $69,523 – $81,846 | $81,846 – $106,493 | $106,493 – $139,511 | $139,511 – $199,035 | $199,035+ | |||

| 1982 | 0% | 12% | 14% | 16% | 19% | 22% | 25% | 29% | 33% | 39% | 44% | 49% | 50% |

Source: Tax Foundation

Tax Reform Act of 1986

Main article: Tax Reform Act of 1986Under the Tax Reform Act of 1986, the top marginal income tax rate of married individuals filling-jointly was lowered from 50% to 28% while the bottom rate was raised from 11% to 15%. The upper income level of the married filing jointly bottom tax rate was increased from $5,720 per year to $29,750 per year while several lower tax brackets were collapsed into two. This act reduced the number of tax brackets from fifteen to four. This is the only tax reform act in history to simultaneously decrease top marginal income tax rates and increase the bottom marginal income tax rates. Capital gains were shifted to income and fell under the same rates. The following table shows each marginal income tax rate for 1986 and 1987, adjusted for inflation.

| Year | $0 – $7,513 | $7,513 – $12,161 | $12,161 – $16,788 | $16,788 – $26,287 | $26,287 – $35,356 | $35,356 – $44,630 | $44,630 – $54,355 | $54,355 – $66,065 | $66,065 – $77,755 | $77,755 – $101,176 | $101,176 – $132,560 | $132,560 – $189,105 | $189,105 – $241,679 | $241,679 – $358,782 | $358,782+ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1986 | 0% | 11% | 12% | 14% | 16% | 18% | 22% | 25% | 28% | 33% | 38% | 42% | 45% | 49% | 50% |

| Year | $0 – $5,926 | $5,926 – $55,305 | $55,305 – $88,883 | $88,883 – $177,766 | $177,766+ | ||||||||||

| 1987 | 11% | 15% | 28% | 35% | 38.5% |

Source: Tax Foundation

Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1993

Main article: Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1993According to the Office of Tax Analysis of the United States Department of the Treasury, the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1993 did the following: changed top marginal income tax rates of married individuals filling-jointly to 36% and 39.6% for the top 1.2% of wage earners and reduced the corporate tax to 35%. The following table shows the changes in the marginal income tax rates from 1992–1994, adjusted for inflation.

| Year | $0 – $57,254 | $57,254 – $138,338 | $138,338+ | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1992 | 15% | 28% | 31% | ||

| Year | $0 – $57,298 | $57,298 – $138,432 | $138,432 – $217,392 | $217,392 – $388,200 | $388,200+ |

| 1993 | 15% | 15% | 28% | 31% | 39.6% |

| Year | $0 – $57,533 | $57,533 – $139,064 | $139,064 – $211,965 | $211,965 – $378,508 | $378,508+ |

| 1994 | 15% | 28% | 31% | 36% | 39.6% |

Source: Tax Foundation

Bush Tax Cuts of 2001, 2003

Main article: Bush tax cutsThe Economic Growth and Tax Relief Reconciliation Act of 2001 made the following changes to the marginal income tax rates: single filers with taxable income up to $6,000, joint filers with income up to $12,000, and heads of households with income up to $10,000 were placed in a new tax bracket of 10%; the 15% bracket's lower threshold was indexed to the new 10% bracket; the 28% bracket was changed to 25%; the 31% bracket was changed to 28%; the 36% bracket was changed to 33%; the 39.6% bracket was changed to 35%. All of these changes took effect by 2006. The act also lowered capital gains taxes on property or stock held for five years to 8% from 10%. Additionally, the following changes were made to the estate tax: The estate tax unified credit exclusion was increased to $1,000,000 in 2002, $1,500,000 in 2004, $2,000,000 in 2006, and $3,500,000 in 2009 from $675,000 in 2001. The estate tax was set to be repealed in 2010 under this legislation. The maximum estate tax was 55% in 2001 with an additional 5% for estates over $10,000,000 and was then reduced to 50% in 2002 with an additional 1% reduction each year until 2007. The top estate tax rate became 45% by 2007. The Jobs and Growth Tax Relief Reconciliation Act of 2003 retroactively enacted the maximum tax rate decreases scheduled for 2006 to the 2003 tax year and reduced capital gains taxes on long-term capital gains from 8%, 10%, and 20%, to 15% and 5%, respectively, for the bottom two tax brackets. Starting in 2008 and extending until 2012, the tax rate on qualified dividends and long term capital gains for the lowest two tax brackets (10% and 15%) will be 0%. The following table shows each marginal income tax rate for 2001 through 2003, adjusted for inflation, which shows the before and after results of the EGTRRA and the JGTRRA.

| Year | $0 – $57,137 | $57,137 – $138,05 | $138,055 – $210,372 | $210,372 – $375,725 | $375,725+ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2001 | 15% | 28% | 31% | 36% | 39.6% | |

| Year | $0 – $14,967 | $14,967 – $58,246 | $58,246 – $140,752 | $140,752 – $214,464 | $214,464 – $382,967 | $382,967+ |

| 2002 | 10% | 15% | 27% | 30% | 35% | 38.6% |

| Year | $0 – $17,072 | $17,072 – $69,265 | $69,265 – $139,810 | $139,810 – $213,039 | $213,039 – $380,409 | $380,409+ |

| 2003 | 10% | 15% | 25% | 28% | 33% | 35% |

Source: Tax Foundation

References

- Study covers years between 1950 and 2006. Berg, Andrew G.; Ostry, Jonathan D. (2011). "Equality and Efficiency". Finance and Development. 48 (3). International Monetary Fund. Retrieved September 10, 2012.

- ^ Tax Foundation.org, "Federal Individual Income Tax Rates History: Inflation Adjusted (Real 2011 Dollars) Using Average Annual CPI During Tax Year".

- Hungerford, Thomas L. (December 29, 2011). Changes in the Distribution of Income Among Tax Filers Between 1996 and 2006: The Role of Labor Income, Capital Income, and Tax Policy (Report 7-5700/R42131). Washington, D.C.: Congressional Research Service. Retrieved 1 January 2014.

- ^ Massey, Douglas S. "The New Geography of Inequality in Urban America." Race, Poverty, and Domestic Policy. New Haven: Yale UP, 2004. 173-87. Print

- Kenty-Drane, Jessica L. African Americans in the U.S. Economy by Thomas M. Shapiro. Lanham, Rowman and Littlefield, 2005. 175-81. Print

- Lubin, Gus. "Wealth And Inequality In America." Business Insider. 9 Apr. 2009. Web. 05 Oct. 2011

- Corcoran, Mary. "Mobility, Persistence, and the Consequences of Poverty for Children: Child and Adult Outcomes." Ed. Sheldon H. Danzinger and Robert H. Haveman. Understanding Poverty. New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 2001. 127-61. Print.

- ^ Install flash.August 30, 2010 (2010-08-30). "Federal Capital Gains Tax Rates, 1988-2011". Tax Foundation. Retrieved 2012-09-07.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - White House: Here's Why You Have To Care About Inequality Timothy Noah | tnr.com| January 13, 2012

- Krugman, Paul (October 20, 2002). "For Richer". The New York Times.

- Winner-Take-All Politics (book) by Jacob S. Hacker and Paul Pierson p. 75

- "CBO Report Shows Rich Got Richer, As Did Most Americans: View". businessweek.com. October 31, 2011.

- Oligarchy, American Style By PAUL KRUGMAN. 3 November 2011

- "The Broken Contract", By George Packer, Foreign Affairs, November/December 2011

- Christoffersen, John (October 14, 2013). "Rising inequality 'most important problem,' says Nobel-winning economist". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. Retrieved 19 October 2013.

- Alesina, Alberto (1994). "Distributive Politics and Economic Growth" (PDF). Quarterly Journal of Economics. 109 (2): 465–90. doi:10.2307/2118470. Retrieved 17 October 2013.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Castells-Quintana, David (2012). "Unemployment and long-run economic growth: The role of income inequality and urbanisation" (PDF). Investigaciones Regionales. 12 (24): 153–173. Retrieved 17 October 2013.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Abel, Andrew B., Ben S. Bernanke, and Dean Croushore. Macroeconomics. 6th ed. New York: Pearson Education, 2008. Print.

- by G. William Domhoff. "Who Rules America: Wealth, Income, and Power". Sociology.ucsc.edu. Retrieved 2012-09-07.

- ^ Domhoff, G. William. Who Rules America?: Power, Politics, and Social Change. Boston: McGraw-Hill Higher Education, 2010. Print.

- Stiglitz, Joseph E. "Of the 1%, by the 1%, for the 1%." Vanity Fair May 2011. Web. 20 Nov. 2011. <http://www.vanityfair.com/society/features/2011/05/top-one-percent-201105>

- "CBO: Top 1% Almost Tripled Incomes, Fueling Wealth Inequality". Retrieved 14 July 2013.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - "OWL-Space CCM" (PDF). Owlspace-ccm.rice.edu. Retrieved 2012-09-07.

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Highlights of Women’s Earnings in 2009. Report 1025, June 2010.

- Lifting as We Climb: Women of Color, Wealth, and America’s Future (PDF). Oakland, California: Insight Center for Community Economic Development. Spring 2010. Retrieved 1 January 2014.

- Kenty-Drane, Jessica L. African Americans in the U.S. Economy. By Thomas M. Shapiro. Lanham, Rowman and Littlefield, 2005. 175-81. Print.

- Massey, Douglas S. "The New Geography of Inequality in Urban America." Race, Poverty, and Domestic Policy. New Haven: Yale UP, 2004. 173-87. Print.

- "The Distribution of Household Income and Federal Taxes, 2010". The US Congressional Budget Office (CBO). 2013-12-04. Retrieved 2014-01-06.

- Lowrey, Annie (2013-01-04). "Tax Code May Be the Most Progressive Since 1979". The New York Times. Retrieved 2014-01-06.

- "Paul Krugman – Income Inequality and the Middle Class". YouTube. Retrieved 2012-09-07.

- By Joseph E. StiglitzIllustration by Stephen Doyle. "Of the 1%, by the 1%, for the 1%". Vanity Fair. Retrieved 2012-09-07.

- Piketty, Thomas, and Emmanuel Saez. INCOME INEQUALITY IN THE UNITED STATES, 1913–1998. Tech. 1st ed. Vol. CXVIII. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 2003. Print.

- Noah, Timothy. "The United States of Inequality." Slate. The Slate Group, 9 Sept. 2010. Web. 13 Nov. 2011. <http://www.slate.com/>.

- Bargain, Olivier, Mathias Dolls, Herwig Immervoll, Dirk Neumann, Andreas Peichl, Nico Pestel, and Sebastian Siegloch. Tax Policy and Income Inequality in the U.S., 1978—2009: A Decomposition Approach. Working paper no. ECINEQ WP 2011 – 215. 2011. Print.

- Kocieniewski, David (2012-01-18). "Since 1980s, the Kindest of Tax Cuts for the Rich". New York Times. Retrieved 2012-01-21.

- "The Hidden Entitlements". CTJ.

- Dickinson, Tom (2011-11-09). "How the GOP Became the Party of the Rich". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 2012-01-02.

- "FactChecking Obama's Budget Speech". FactCheck.org. 2011-04-15. Retrieved 2011-01-04.

- Noah, Timothy. "The United States of Inequality." Slate.com. The Slate Group, 9 Sept. 2010. Web. 16 Nov. 2011. <http://www.slate.com/>

- "Historical Effective Tax Rates, 1979 to 2005: Supplement with Additional Data on Sources of Income and High-Income Households" (PDF). CBO. 2008-12-23. Retrieved 2012-05-27.

- Cohen, Isabelle; Freiling, Thomas; Robinson, Eric (January 2012). The Economic Impact and Financing of Infrastructure Spending (PDF) (report). Williamsburg, Virginia: Thomas Jefferson Program in Public Policy, College of William & Mary. p. 5. Retrieved October 1, 2012.

- Pereira, Alfredo (1999). Is All Public Capital Created Equal (peer reviewed paper). Review of Economics and Statistics, 82(3): 513-518.

- Bosworth, Barry; Burtless, Gary; Steuerle, C. Eugene (December 1999). Lifetime Earnings Patterns, the Distribution of Future Social Security Benefits, and the Impact of Pension Reform (PDF) (report no. CRR WP 1999-06). Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts: Center for Retirement Research at Boston College. p. 43. Retrieved October 1, 2012.

- Reich, Robert B., Emmanuel Saez, and Thomas Piketty. The State of Working America. Publication. Economic Policy Institute, 2011. Print.

- Becker, Gary S., and Kevin M. Murphy. "The Upside of Income Inequality." The America May 2007. Web. 20 Nov. 2011. <http://www.american.com/archive/2007/may-june-magazine-contents/the-upside-of-income-inequality>.

- Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 15755330, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=15755330instead. - "The Distribution of Household Income and Federal Taxes, 2010". The US Congressional Budget Office (CBO). 2013-12-04. Retrieved 2014-01-06.

- http://www.encyclopedia.com/searchresults.aspx?q=progressive+tax

- ^ Böhm, Volker. "Demand Theory." The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics,. Ed. Hans Haller. Vol. 1. Palgrave MacMillan, 1987. 785-92. Print.

- ^

- September 14, 2010 (2010-09-14). "Federal Capital Gains Tax Collections, 1954-2009". Tax Foundation. Retrieved 2012-09-07.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Domhoff, G. William. Who Rules America?: Power, Politics, and Social Change. Boston: McGraw-Hill Higher Education, 2010. Print.

- "CBO | Federal Estate and Gift Taxes". Cbo.gov. 2009-12-18. Retrieved 2012-09-07.

- "Estate tax in the United States – Misplaced Pages, the 💕". En.wikipedia.org. Retrieved 2012-09-07.

External links

| This article's use of external links may not follow Misplaced Pages's policies or guidelines. Please improve this article by removing excessive or inappropriate external links, and converting useful links where appropriate into footnote references. (January 2014) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

- http://taxfoundation.org

- http://elsa.berkeley.edu/~saez/pikettyqje.pdf

- http://www2.ucsc.edu/whorulesamerica/power/wealth.html

- http://www.natptax.com/taxact2003.pdf/

- http://www.slate.com/articles/news_and_politics/the_great_divergence/features/2010/the_united_states_of_inequality/introducing_the_great_divergence.html