This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Materialscientist (talk | contribs) at 22:43, 25 March 2014 (fmt). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 22:43, 25 March 2014 by Materialscientist (talk | contribs) (fmt)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)

In biology, cell theory is a scientific theory that describes the properties of cells, which are the basic unit of structure in all organisms and also the basic unit of reproduction. The initial development of the theory, during the mid-17th century, was made possible by advances in microscopy; the study of cells is called cell biology. Cell theory is one of the foundations of biology.The observations of Robert Hooke, Anton van Leeuwenhoek, Matthias Schleiden, Theodor Schwann, Rudolf Virchow, and others led to the development of the cell theory. The cell theory is a widely accepted explanation of the relationship between cells and living things.

The three tenets to the cell theory are as described below:

- All living organisms are composed of one or more cells

- The cell is the most basic unit of life.

- All cells arise from pre-existing, living cells.

Microscopes

The discovery of the cell was made possible through the invention of the microscope. In the first century BC, Romans were able to make glass, discovering that objects appeared to be larger under the glass. In Italy during the 12th century, Salviano D’Armate made a piece of glass to fit over one eye, allowing for a magnification effect to that eye. It wasn’t until the 1590’s when a Dutch spectacle maker Zacharias Jansen began to test lenses that progress had been made to microscopes. Jansen was able to obtain about 9x magnification, but the objects appeared to be blurry. In 1595, Jansen and his father built the first compound microscope. While simple glasses were able to magnify objects, they were not considered to be a microscope. A compound microscope was defined by having two or more lenses in a hollow tube.

However, the first real invention and use of a microscope was by Anton van Leeuwenhoek. He was a Dutch draper that took interest in microscopes after seeing one while on an apprenticeship in Amsterdam in 1648. At some point in his life before 1668, he was able to learn how to grind lenses. This eventually led to Leeuwenhoek making his own microscope. His were instead simple powerful magnifying glasses, rather than a compound microscope. This was because he was able to use a single lens that was a small glass sphere but allowed for a magnification of 270x. This was a large progression since the magnification before was only a maximum of 50x. After Leeuwenhoek, there was not much progress for the microscopes until the 1850’s, two hundred years later. Carl Zeiss, a German engineer who manufactured microscopes, began to make changes to the lenses used. But the optical quality did not improve until the 1880’s when he hired Otto Schott and eventually Ernst Abbe.

These microscopes could focus on objects the size of a wavelength or larger, giving restrictions still to advancement in discoveries with objects smaller than a wavelength. Later in the 1920’s, the electron microscope was developed, making it possible to view objects that are smaller than a wavelength, once again, changing the possibilities in science.

History

The cell was first discovered by Robert Hooke in 1665, which can be found to be described in his book Micrographia. In this book, he gave 60 ‘observations’ in detail of various objects under a coarse, compound microscope. One observation was from very thin slices of bottle cork. Hooke discovered a multitude of tiny pores that he named "cells". This came from the Latin word Cella, meaning ‘a small room’ like monks lived in and also Cellulae, which meant the six sided celled of a honeycomb. However, Hooke did not know their real structure or function.

What Hooke had thought were cells, were actually empty cell walls of plant tissues. With microscopes during this time having a low magnification, Hooke was unable to see that there were other internal components to the cells he was observing. Therefore, he did not think the "cellulae" was alive. His cell observations gave no indication of the nucleus and other organelles found in most living cells.

One of the first to witness living cells under a microscope was Anton van Leeuwenhoek,who made use of a microscope containing much better lenses that could magnify objects almost 300-fold(Becker,kleinsmith,hardin,p. 1). In 1674 Leeuwenhoek described the algae Spirogyra and named the moving organisms animalcules, meaning "little animals". Leeuwenhoek probably also saw bacteria. Bacteria are microscopic (very tiny) organisms that are unicellular (made up of a single cell). Cell theory was in contrast to the vitalism theories proposed before the discovery of cells. The idea that cells were separable into individual units was proposed by Ludolph Christian Treviranus and Johann Jacob Paul Moldenhawer. All of this finally led to Henri Dutrochet formulating one of the fundamental tenets of modern cell theory by declaring that "The cell is the fundamental element of organization".

The cell theory holds true for all living things, no matter how big or small. Since according to research, cells are common to all living things, they can provide information about all life. And because all cells come from other cells, scientists can study cells to learn about growth, reproduction, and all other functions that living things perform. By learning about cells and how they function, you can learn about all types of living things. Cells are the building blocks of life.

Credit for developing cell theory is usually given to three scientists: Theodor Schwann, Matthias Jakob Schleiden, and Rudolf Virchow. In 1839, Schwann and Schleiden suggested that cells were the basic unit of life. Their theory accepted the first two tenets of modern cell theory (see next section, below). However, the cell theory of Schleiden differed from modern cell theory in that it proposed a method of spontaneous crystallization that he called "free cell formation". In fact, Schleiden's theory of free cell formation was refuted in the 1850s by Robert Remark,Rudolf Virchow and Albert Kolliker. In 1855, Rudolf Virchow concluded that all cells come from pre-existing cells, thus completing the classical cell theory. (Note that the idea that all cells come from pre-existing cells had in fact already been proposed by Robert Remak; it has been suggested that Virchow plagiarised Remak.)

Modern interpretation

The generally accepted parts of modern cell theory include:

- All known living things are made up of one or more cells

- All living cells arise from pre-existing cells by division. (This was stated by Rudolf Virchow after studying the growth of cells in human tissues.)

- The cell is the fundamental unit of structure and function in all living organisms.

- The activity of an organism depends on the total activity of independent cells.

- Energy flow (metabolism and biochemistry) occurs within cells.

- Cells contain DNA which is found specifically in the chromosome and RNA found in the cell nucleus and cytoplasm.

- All cells are basically the same in chemical composition in organisms of similar species .

Types of cells

Cells can be subdivided into the following subcategories:

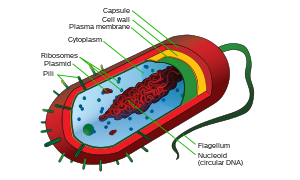

- Prokaryotes: Prokaryotes are relatively small cells surrounded by the plasma membrane, with a characteristic cell wall that may differ in composition depending on the particular organism. Prokaryotes lack a nucleus (although they do have circular or linear DNA) and other membrane-bound organelles (though they do contain ribosomes). The protoplasm of a prokaryote contains the chromosomal region that appears as fibrous deposits under the microscope, and the cytoplasm. Bacteria and Archaea are the two domains of prokaryotes.

- Eukaryotes: Eukaryotic cells are also surrounded by the plasma membrane, but on the other hand,they have distinct nuclei bound by a nuclear membrane or envelope. Eukaryotic cells also contain membrane-bound organelles, such as (mitochondria, chloroplasts, lysosomes, rough and smooth endoplasmic reticulum, vacuoles). In addition, they possess organized chromosomes which store genetic material.

See also

References

- "History of the Microscope". History-of-the-microscope.org, United Kingdom. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1038/8964, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1038/8964instead. - Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 15209075, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=15209075instead. - Inwood, Stephen (2003). The man who knew too much: the strange and inventive life of Robert Hooke, 1635–1703. London: Pan. p. 72. ISBN 0-330-48829-5.

- Becker, Wayne M.; Kleinsmith, Lewis J. and Hardin, Jeff (2003). The World of the Cell. Benjamin/Cummings Publishing Company. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-8053-4854-5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Moll WAW (2006). "Antonie van Leeuwenhoek". Archived from the original on 2008-06-02. Retrieved 2008-11-25.

- Porter JR (1976). "Antony van Leeuwenhoek: tercentenary of his discovery of bacteria". Bacteriol Rev. 40 (2): 260–9. PMC 413956. PMID 786250.

- Col, Jeananda. "Bacteria". EnchantedLearning.com. Retrieved 19 September 2013.

- Treviranus, Ludolph Christian (1811) "Beyträge zur Pflanzenphysiologie"

- Moldenhawer, Johann Jacob Paul (1812) "Beyträge zur Anatomie der Pflanzen"

- Dutrochet, Henri (1824) "Recherches anatomiques et physiologiques sur la structure intime des animaux et des vegetaux, et sur leur motilite, par M.H. Dutrochet, avec deux planches"

- Schleiden, Matthias Jakob (1839) "Contributions to Phytogenesis"

- Silver, GA (1987). "Virchow, the heroic model in medicine: health policy by accolade". American Journal of Public Health. 77 (1): 82–8. doi:10.2105/AJPH.77.1.82. PMC 1646803. PMID 3538915.

- Wolfe

- Wolfe

- Wolfe, p. 5

- Wolfe, p. 8

- ^ Wolfe, p. 11

- Wolfe, p. 13

Bibliography

- Wolfe, Stephen L. (1972). Biology of the cell. Wadsworth Pub. Co. ISBN 978-0-534-00106-3.

Further reading

- Turner W (January 1890). "The Cell Theory Past and Present". J Anat Physiol. 24 (Pt 2): 253–87. PMC 1328050. PMID 17231856.

- Tavassoli M (1980). "The cell theory: a foundation to the edifice of biology". Am. J. Pathol. 98 (1): 44. PMC 1903404. PMID 6985772.

External links

- Mallery C (2008-02-11). "Cell Theory". Retrieved 2008-11-25.

- "Studying Cells Tutorial". 2004. Retrieved 2008-11-25.