This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Clean Copy (talk | contribs) at 11:10, 28 June 2006 (→Presidency: 1789 – 1797: clarify runner up to a unanimous election). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 11:10, 28 June 2006 by Clean Copy (talk | contribs) (→Presidency: 1789 – 1797: clarify runner up to a unanimous election)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) For other people named George Washington, see George Washington (disambiguation).| George Washington | |

|---|---|

| |

| 1st President of the United States | |

| In office April 30 1789 – March 3 1797 | |

| Vice President | John Adams |

| Preceded by | None |

| Succeeded by | John Adams |

| Personal details | |

| Born | February 22 1732 Westmoreland County, Virginia |

| Died | December 14 1799 Mount Vernon, Virginia |

| Nationality | American |

| Spouse | Martha Dandridge Custis Washington |

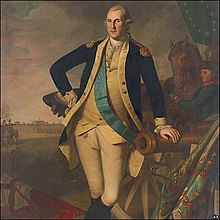

George Washington (February 22, 1732 – December 14, 1799) was the Commander in Chief of American forces in the American Revolutionary War (1775–1783), and, later, the first President of the United States, an office he held from 1789 to 1797. Because of his central role in the founding of the United States, Washington is often called the "Father of his Country". Scholars rank him among the greatest of United States presidents.

Washington first gained prominence leading troops from Virginia in support of the British Empire during the French and Indian War (1754–1763), a conflict which he inadvertently helped to start. After leading the American victory in the Revolutionary War, he relinquished his military power and returned to civilian life, an act that brought him much renown. In 1787, he presided over the Constitutional Convention that drafted the United States Constitution and, in 1789, was the unanimous choice to become the first President of the United States. His two-term administration set many policies and traditions that survive today. After his second term expired, Washington again retired to civilian life, establishing an important precedent of peaceful change of government that was to serve as an example for the United States and for other future republics.

Early life

According to the Julian calendar, Washington was born on February 11, 1731; according to the Gregorian calendar, which was adopted in Britain and its colonies during Washington's lifetime and is still used today, he was born on February 22, 1732. Washington's Birthday is a national holiday in the United States. His birthplace was Popes Creek Plantation, on the Potomac River southeast of modern-day Colonial Beach in Template:USCity. Washington's ancestors were from Washington Old Hall, Washington, England; his great-grandfather, John Washington, immigrated to Virginia in 1657. George's father Augustine "Gus" Washington (1693–1743) was a slave-owning planter who later tried his hand in iron-mining ventures. His mother, Mary Ball Washington (1708–1789), lived to see her son become famous, though she had a strained relationship with him. In George's youth, the Washingtons were moderately prosperous members of the Virginia gentry, of "middling rank" rather than one of the leading families.

Washington, the oldest child from his father's second marriage, had two older half-brothers and four younger siblings. Gus Washington died when George was eleven years old, after which George's half-brother Lawrence Washington became a surrogate father and role model. William Fairfax, Lawrence's father-in-law and a member of the powerful Fairfax family, was also a formative influence. Washington spent much of his boyhood at Ferry Farm in Stafford County near Fredericksburg. Lawrence Washington inherited another family property from his father, which he later named Mount Vernon. George inherited Ferry Farm upon his father's death, and eventually acquired Mount Vernon after Lawrence's death.

The death of his father prevented Washington from receiving an education in England as his older brothers had done. He had little formal schooling, and, in later life, was somewhat self-conscious that he was less learned than some of his contemporaries. As a teenager, Washington received training as a surveyor. Thanks to his Fairfax connections, at seventeen he was appointed official surveyor for Culpeper County in 1749, a well-paid position which allowed him to purchase land in the Shenandoah Valley, the first of his many land acquisitions in western Virginia. He also conducted surveys for the Ohio Company, which brought him to the notice of the lieutenant governor of Virginia, Robert Dinwiddie. Washington was hard to miss: at about six feet two inches (estimates of his height have varied), he towered over most of his contemporaries.

In 1751, Washington traveled to Barbados with Lawrence, who was suffering from tuberculosis, with the hope that the climate would be beneficial to Lawrence's health. Washington contracted smallpox during the trip, which left his face slightly scarred, but gave him immunity to the dreaded disease in the future. Lawrence's health did not improve: he returned to Mount Vernon, where he died in 1752. Lawrence's position as Adjutant General of Virginia (a militia leadership role) was divided into four offices after his death. Washington was appointed by Governor Dinwiddie as one of the four district adjutants, with the rank of major in the Virginia militia. Washington also joined the Freemasons in Fredericksburg at this time.

French and Indian War

At twenty-two years of age, Washington fired some of the first shots of what would become a world war. The trouble began in 1753, when France began building a series of forts in the Ohio Country, a region also claimed by Virginia. Governor Dinwiddie sent young Major Washington to the Ohio Country to assess French military strength and intentions, and to deliver a letter to the French commander, which asked them to leave. The French declined to leave, but Washington became well-known after his account of the journey was published in both Virginia and England, since most English-speaking people knew little about lands on the other side of the Appalachian Mountains at the time.

In 1754, Dinwiddie sent Washington, now commissioned a Lieutenant Colonel in the newly created Virginia Regiment, on another mission to the Ohio Country, this time to drive the French away. Along with his American Indian allies, Washington and his troops ambushed a French Canadian scouting party, killing the French commander, Ensign Jumonville. Washington then built Fort Necessity, which soon proved inadequate, as he was soon compelled to surrender to a larger French and American Indian force. The surrender terms that Washington signed included an admission that he had "assassinated" Jumonville. (The document was written in French, which Washington could not read.) Because the French claimed that Jumonville's party had been on a diplomatic (rather than military) mission, the "Jumonville affair" became an international incident and helped to ignite the French and Indian War, a part of the worldwide Seven Years' War. Washington was released by the French with his promise not to return to the Ohio Country for one year. Back in Virginia, Governor Dinwiddie broke up the Virginia Regiment into independent companies; Washington resigned from active military service rather than accept a demotion to captain.

One year later, British General Edward Braddock headed a major effort to retake the Ohio Country. Washington eagerly volunteered to serve as one of Braddock's aides. The expedition ended in disaster at the Battle of the Monongahela. Washington distinguished himself in the debacle—he had two horses shot out from under him, and four bullets pierced his coat—yet, he sustained no injuries and showed coolness under fire. In Virginia, Washington was acclaimed as a hero, and he was reappointed as commander of the Virginia Regiment. Although the focus of the war had shifted elsewhere, Washington spent the next several years guarding the Virginia frontier against American Indian raids. In 1758, he took part in the Forbes Expedition, which successfully drove the French away from Fort Duquesne.

Between the wars

Washington's goal at the outset of his military career had been to secure a commission as a British officer, which had more prestige than serving in the provincial military. The promotion did not come, and so, in 1758, Washington resigned his commission. In 1759 he married Martha Dandridge Custis, a wealthy widow, although surviving letters suggest that Washington was in love with Sally Fairfax, the wife of a friend, at the time. Nevertheless, George and Martha had a good marriage, and together raised her two children, John Parke Custis and Martha Parke Custis, affectionately called "Jacky" and "Patsy". Later the Washingtons raised two of Mrs. Washington's grandchildren, Eleanor Parke Custis and George Washington Parke Custis. George and Martha never had any children together-—his earlier bout with smallpox followed, possibly, by tuberculosis may have made him sterile.

The newlywed couple moved to Mount Vernon, where he took up the life of a genteel planter and political figure. He held local office and was elected to the Virginia provincial legislature, the House of Burgesses. Washington farmed roughly 8,000 acres (32 km²). Like many Virginia planters at the time, he lived an expensive lifestyle, and thus had little cash on hand and was frequently in debt. Because of the uncertainties of the tobacco market, in the 1760s he switched his primary cash crop from tobacco to wheat, which improved his financial situation. He purchased as much land as he could, and was granted land in what is now West Virginia as a bounty for his service in the French and Indian War. Through natural increase and additional purchases by Washington, by 1775 the slave population at Mount Vernon exceeded 100.

American Revolution

Further information: ]

In 1774, Washington was chosen as a delegate from Virginia to the First Continental Congress, which convened in the wake of Britain's punitive measures taken against the colony of Massachusetts. After fighting broke out at Lexington and Concord in April 1775, Washington appeared at the Second Continental Congress in military uniform, signaling that he was prepared for war. To coordinate the military efforts of the Thirteen Colonies, Congress created the Continental Army on June 14; the next day it selected Washington as commander-in-chief. Massachusetts delegate John Adams had nominated Washington, believing that appointing a southerner to lead what was at this stage primarily an army of northerners would help unite the colonies. Washington reluctantly accepted, declaring "with the utmost sincerity, I do not think myself equal to the Command I honoured with." He asked for no pay other than reimbursement of his expenses.

Washington assumed command of the American forces in Massachusetts on July 3, 1775, during the ongoing siege of Boston. Washington reorganized the army during the long standoff, which finally ended on March 17, 1776, after artillery was placed upon Dorchester Heights. The British evacuated Boston for temporary refuge in Halifax, and Washington moved his army to New York City. In August 1776, British General William Howe launched a successful campaign to capture New York, beginning a series of devastating defeats for Washington. He lost the Battle of Long Island on August 22, but managed to evacuate most of his forces to the mainland. Several other defeats sent Washington scrambling across New Jersey, leaving the future of the Continental Army in doubt. On the night of December 25, 1776, Washington staged a celebrated counterattack, leading the American forces across the Delaware River to capture nearly 1,000 Hessians in Trenton, New Jersey. Washington followed up the assault with a surprise attack on British forces at Princeton. These unexpected victories after a series of losses gave a morale boost to the Revolutionary cause.

In 1777, General Howe began a campaign to capture Philadelphia. Washington moved south to block Howe's army, but was defeated at the Battle of Brandywine on September 11, 1777. On September 26, Howe outmaneuvered Washington and marched into Philadelphia unopposed. Washington's army unsuccessfully attacked the British garrison at Germantown in early October and then encamped at Valley Forge in December, where they stayed for the next six months. Over the winter, 2,500 men (out of 10,000) died from disease and exposure. The next spring, however, the army emerged from Valley Forge in good order, thanks in part to a training program supervised by Baron von Steuben.

Meanwhile, a second British expedition in 1777 had far-reaching consequences. General John Burgoyne had marched from Canada in an effort to sever New England from the other colonies, but was forced to surrender at Saratoga on October 17. This turn of events ultimately convinced France to sign a formal alliance with the United States in 1778. The victory at Saratoga was in stark contrast to Washington's loss of Philadelphia, prompting some members of Congress to secretly discuss removing Washington from command. This episode—later known as the "Conway Cabal"—failed after Washington's supporters rallied behind him.

French entry into the war changed everything. The British evacuated Philadelphia in 1778 and returned to New York City, with Washington attacking them along the way. This was the last major battle in the north; thereafter, the British focused on recapturing the Southern states while fighting the French (and later, the Spanish and the Dutch) elsewhere around the globe. During this time, Washington remained with his army outside New York, looking for an opportunity to strike a decisive blow while dispatching other operations to the north and south. The long-awaited opportunity finally came in 1781, after a French naval victory allowed American and French forces to trap a British army in Virginia. The surrender at Yorktown on October 17, 1781 prompted the British to negotiate an end to the war. The Treaty of Paris (1783) recognized the independence of the United States.

Washington's contribution to victory in the American Revolution was not that of a great battlefield tactician; in fact, he lost more battles than he won, and he sometimes planned operations that were too complicated for his amateur soldiers to execute. However, his overall strategy proved to be the correct one: keep the army intact, wear down British resolve, and avoid decisive battles except to exploit enemy mistakes. Washington was a military conservative: he preferred building a regular army on the European model and fighting a conventional war.

One of Washington's most important contributions as commander-in-chief was to establish the precedent that civilian elected officials, rather than military officers, possessed ultimate authority over the military. Throughout the war, he deferred to the authority of Congress and state officials, and he relinquished his considerable military power once the fighting was over. In March 1783, Washington used his influence to disperse a group of Army officers who had threatened to confront Congress regarding their back pay. Washington disbanded his army and, on November 2, gave an eloquent farewell address to his soldiers. A few days later, the British evacuated New York City, and Washington and the governor took possession of the city; at Fraunces Tavern in the city on December 4, he formally bade his officers farewell. On December 23, 1783, Washington resigned his commission as commander-in-chief to the Congress of the Confederation.

Washington's retirement to Mount Vernon was short-lived. He was persuaded to attend the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia in the summer of 1787, and he was unanimously elected president of the Convention. For the most part, he did not participate in the debates involved, but his prestige was great enough to maintain collegiality and to keep the delegates at their labors. He adamantly enforced the secrecy adopted by the Convention during the summer. Many believe that the Founding Fathers created the presidency with Washington in mind. After the Convention, his support convinced many, including the Virginia legislature, to support the Constitution.

Presidency: 1789 – 1797

Washington was elected unanimously by the Electoral College in 1789, and he remains the only person ever to be elected president unanimously (a feat which he duplicated in the 1792 election). As runner-up with 34 votes (each elector cast two votes), John Adams became vice president-elect. The First U.S. Congress voted to pay Washington a salary of $25,000 a year—a significant sum in 1789. Washington, already wealthy, declined the salary, since he valued his image as a selfless public servant. Washington attended carefully to the pomp and ceremony of office, making sure that the titles and trappings were suitably republican and never emulated European royal courts.

Washington only reluctantly agreed to serve a second term of office as president. He refused to run for a third, establishing an unwritten precedent of a maximum of two terms for a U.S. president. After Franklin Delano Roosevelt was elected to an unprecedented four terms, the two term limit was formally integrated into the Federal Constitution by the 22nd Amendment.

Domestic issues

Washington was not a member of any political party, and hoped that they would not be formed. His closest advisors, however, became divided into two factions, setting the framework for political parties. Secretary of Treasury Alexander Hamilton, who had bold plans to establish the national credit and build a financially powerful nation, formed the basis of the Federalist Party. Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson, founder of the Jeffersonian Republicans, opposed Hamilton's agenda. Washington publicly remained uninvolved in party politics, though his decisions generally favored Hamilton, which eventually prompted Jefferson to leave the administration.

In 1791, Congress imposed an excise tax on distilled spirits, which led to protests. By 1794, after Washington ordered the protesters to appear in U.S. district court, the protests turned into full-scale riots known as the Whiskey Rebellion. On August 7, Washington invoked the Militia Law of 1792 to summon the militias of Pennsylvania, Virginia and several other states. He raised an army of militiamen and marched at its head into the rebellious districts. There was no fighting, but Washington's forceful action proved the new government could protect itself. In leading the military force against the rebels, Washington became the only president to personally lead troops in battle as president. It also marked the first time under the new constitution that the federal government had used strong military force to exert authority over the states and citizens.

Foreign affairs

In 1793, the revolutionary government of France sent diplomat Edmond-Charles Genêt to America. He attempted to turn popular sentiment towards American involvement in the war against Great Britain. Genêt was authorized by France to issue letters of marque and reprisal to American ships and gave authority to any French consul to serve as a prize court. Genêt's activities forced Washington to ask the French government for his recall.

The Jay Treaty, named after Chief Justice of the United States John Jay, who Washington sent to London to negotiate an agreement, was a treaty between the United States and Great Britain signed on November 19 1794. The treaty attempted to clear up some of the lingering problems of American separation from Great Britain following the Revolutionary War. The Jeffersonians supported France and strongly attacked the treaty. Washington, however, obtained its ratification by Congress, which was supported by Hamilton. The British had to clear out of their forts around the Great Lakes. The treaty remained in effect until the War of 1812.

Farewell Address

Washington's Farewell Address (issued as a public letter) was the defining statement of Federalist Party principles and one of the most influential statements of American political values. Most of the address dealt with the dangers of bitter partisanship in domestic politics. He called for men to put aside party affiliations and unite for the common good. He called for an America wholly free of foreign attachments, as the United States must concentrate only on American interests. He counseled friendship and commerce with all nations, but warned against involvement in European wars and entering into long-term alliances. The address quickly entered the realm of "received wisdom". Many Americans, especially in subsequent generations, accepted Washington's advice and, in any debate between neutrality and involvement in foreign issues, would invoke the message as dispositive of all questions. Not until 1949 would the United States again sign a treaty of alliance with a foreign nation.

Speeches

Inaugural Addresses

- First Inaugural Address, (April 30th, 1789)

- Second Inaugural Address, (March 4th, 1793)

State of the Union Address

- First State of the Union Address, (8 January 1790)

- Second State of the Union Address, (8 December 1790)

- Third State of the Union Address, (25 October 1791)

- Fourth State of the Union Address, (6 November 1792)

- Fifth State of the Union Address, (3 December 1793)

- Sixth State of the Union Address, (19 November 1794)

- Seventh State of the Union Address, (8 December 1795)

- Eighth State of the Union Address, (7 December 1796)

Major legislation

- Judiciary Act of 1789

- Indian Intercourse Acts, starting in 1790

- Residence Act of 1790

- Bank Act of 1791

- Coinage Act of 1792 or Mint Act

- Fugitive Slave Act of 1793

- Naval Act of 1794

- Organized the first United States Cabinet and the Executive Branch

Administration and cabinet

| OFFICE | NAME | TERM |

| President | George Washington | 1789–1797 |

| Vice President | John Adams | 1789–1797 |

| Secretary of State | Thomas Jefferson | 1789–1793 |

| Edmund Randolph | 1794–1795 | |

| Timothy Pickering | 1795–1797 | |

| Secretary of the Treasury | Alexander Hamilton | 1789–1795 |

| Oliver Wolcott, Jr. | 1795–1797 | |

| Secretary of War | Henry Knox | 1789–1794 |

| Timothy Pickering | 1795–1796 | |

| James McHenry | 1796–1797 | |

| Attorney General | Edmund Randolph | 1789–1793 |

| William Bradford | 1794–1795 | |

| Charles Lee | 1795–1797 | |

| Postmaster General | Samuel Osgood | 1789–1791 |

| Timothy Pickering | 1791–1795 | |

| Joseph Habersham | 1795–1797 | |

Supreme Court appointments

As the first President, Washington appointed the entire first Supreme Court of the United States:

- John Jay - Chief Justice - 1789

- James Wilson - 1789

- John Rutledge - 1790

- William Cushing - 1790

- John Blair - 1790

- James Iredell - 1790

- Thomas Johnson - 1792

- William Paterson - 1793

- John Rutledge - Chief Justice, 1795 (an associate justice 1790-1795)

- Samuel Chase - 1796

- Oliver Ellsworth - Chief Justice - 1796

States admitted to Union

- North Carolina – November 21, 1789 by ratification of the Constitution

- Rhode Island – May 29, 1790 by ratification of the Constitution

- Vermont – May 4, 1791

- Kentucky – June 1, 1792

- Tennessee – June 1, 1796

Retirement and death

Once Washington retired he opened a distillery in Mount Vernon and became the largest distiller of whiskey at the time, producing 11,000 US gallons (42,000 l) of whiskey and a profit of $7,500 in 1798.

After retiring from the presidency in March 1797, Washington returned to Mount Vernon with a profound sense of relief. In 1798, Washington was appointed Lieutenant General in the United States Army (then the highest possible rank) by President John Adams. Washington's appointment was to serve as a warning to France, with which war seemed imminent.

In 1799, Washington fell ill from a bad cold with a fever and a sore throat that turned into acute laryngitis and pneumonia; he died on December 14, 1799, at his home, while attended by Dr. James Craik, one of his closest friends. Modern doctors believe that Washington died from either epiglottitis or, since he was bled as part of the treatment, a combination of shock from the loss of five pints of blood, as well as asphyxia and dehydration. Washington's remains were buried at Mount Vernon. In order to protect their privacy, Martha Washington burned the correspondence between her husband and herself following his death. Only three letters between the couple have survived.

Legacy

Congressman Henry Light Horse Harry Lee, a Revolutionary War comrade, famously eulogized Washington as "a citizen, first in war, first in peace, and first in the hearts of his countrymen." Washington set many precedents that established tranquility in the presidential office in the years to come. His choice to peacefully relinquish the presidency to John Adams, after serving two terms in office, is seen as one of Washington's most important legacies.

He was also lauded as the "Father of His Country" and is often considered to be the most important of Founding Fathers of the United States. He has gained fame around the world as a quintessential example of a benevolent national founder. Washington also ranked number twenty-six in Michael H. Hart's list of the most influential figures in history, and historians generally regarded him as one of the greatest presidents.

Washington was long considered not just a military and revolutionary hero, but a man of great personal integrity, with a deeply held sense of duty, honor and patriotism. He was upheld as a shining example in schoolbooks and lessons: as courageous and farsighted, holding the Continental Army together through eight hard years of war and numerous privations, sometimes by sheer force of will; and as restrained: at war's end taking affront at the notion he should be King; and after two terms as President, stepping aside.

In recent years, schools and authors have focused more on his weaknesses: his ownership of the family plantation and its slaves and his role in the French and Indian War. Traditionally, students have been taught to look to Washington as a character model more even than war hero or founding father. To them, Washington was notable for his modesty and carefully controlled ambition.

It is often said that one of Washington's greatest achievements was refraining from taking more power than was due. He was conscientious of maintaining a good reputation by avoiding political intrigue. He had no interest in nepotism or cronyism, rejecting, for example, a military promotion during the war for his deserving cousin William Washington lest it be regarded as favoritism. Thomas Jefferson wrote, "The moderation and virtue of a single character probably prevented this Revolution from being closed, as most others have been, by a subversion of that liberty it was intended to establish."

Monuments and memorials

Today, Washington's face and image are often used as national symbols of the United States, along with the icons such as the flag and great seal. Perhaps the most pervasive commemoration of his legacy is the use of his image on the one-dollar bill and the quarter-dollar coin. Washington, together with Theodore Roosevelt, Thomas Jefferson, and Abraham Lincoln, is depicted in stone at the Mount Rushmore Memorial.

Many things have been named in honor of Washington. The capital city of the United States, Washington, D.C., is named for him. The Washington Monument, one of the most well-known American landmarks, was built in his honor. The George Washington University, also in D.C., was named after him, and it was founded in part with shares Washington bequeathed to an endowment to create a national university in Washington. The only state named for a president is the state of Washington. The United States Navy has named three ships after Washington. The George Washington Bridge, which extends between New York City and New Jersey, and the palm tree genus Washingtonia, are also named after him.

Even though he had been the highest-ranking officer of the Revolutionary War, having in 1798 been appointed a Lieutenant General (now three stars), it seemed, somewhat incongruously, that all later full four star and higher generals were considered to outrank Washington. This issue was resolved in the bicentennial year of 1976 when Washington was, by act of Congress, posthumously promoted to the rank of General of the Armies, this promotion being backdated to July 4, 1776, making Washington permanently the senior military officer of the United States.

Washington and slavery

For most of his life, Washington was a typical Virginia slave owner. At the age of eleven, he inherited ten slaves; by the time of his death there were 317 slaves at Mount Vernon, including 124 owned by Washington, 40 leased from a neighbor, and an additional 153 "dower slaves" which were controlled by Washington but were the property of Martha's first husband's estate. As on other plantations, his slaves worked from dawn until dusk unless injured or ill and they were whipped for running away or for other infractions. They were fed, clothed, and housed as inexpensively as possible, in conditions that were probably quite meager. Visitors recorded contradictory impressions of slave life at Mount Vernon: one visitor in 1798 wrote that Washington treated his slaves "with more severity" than his neighbors, while another around the same time stated that "Washington treats his slaves far more humanely than do his fellow citizens of Virginia."

Historian Henry Wiencek speculates that Washington's slave buying, particularly his participation in a raffle of 55 slaves in 1769 which broke up slave families, may have initiated his gradual reassessment of slavery. Whatever the cause, by 1778 Washington had stopped selling slaves without their consent because he did not want to break up families. His thoughts on slavery may have also been influenced by the rhetoric of the American Revolution, by the thousands of blacks who sought to enlist in the army, by the anti-slavery sentiments of his idealistic aide John Laurens, and by the enslaved black poet Phillis Wheatley, who in 1775 wrote a poem in his honor. In 1778, while Washington was at war, he wrote to his manager at Mount Vernon that he wished sell his slaves and "to get quit of negroes", since maintaining a large (and increasingly elderly) slave population was no longer economically efficient. Washington could not legally sell the "dower slaves", however, and because these slaves had long intermarried with his own slaves, he could not sell his slaves without breaking up families, something which he had resolved not to do. Confronted with this dilemma, his plan to divest himself of slaves was dropped.

After the war, Washington often privately expressed a dislike of the institution of slavery. In 1786, he wrote to a friend that "I never mean ... to possess another slave by purchase; it being among my first wishes to see some plan adopted, by which slavery in this Country may be abolished by slow, sure and imperceptible degrees." To another friend he wrote that "there is not a man living who wishes more sincerely than I do to see some plan adopted for the abolition" of slavery. He expressed moral support for plans by his friend the Marquis de Lafayette to emancipate slaves and resettle them elsewhere, but he did not assist him in the effort.

Despite these privately expressed misgivings, Washington never criticized slavery in public. In fact, as President, Washington brought eight household slaves with him to the Executive Mansion in Philadelphia. By Pennsylvania law, slaves who resided in the state became legally free after six months. Washington rotated his household slaves between Mount Vernon and Philadelphia so that they did not earn their freedom, a scheme he attempted to keep hidden from his slaves and the public. Two slaves escaped while in Philadelphia: one of these, Ona Judge, was located in New Hampshire. Judge could have been captured and returned under the Fugitive Slave Act, which Washington had signed into law in 1793, but this was not done so as to avoid public controversy.

Washington was the only prominent, slaveholding Founding Father to emancipate his slaves. He did not free his slaves in his lifetime, however, but instead included a provision in his will to free his slaves upon the death of his wife. William Lee, Washington's longtime personal servant, was the only slave freed outright in the will. The will called for the ex-slaves to be provided for by Washington's heirs, the elderly ones to be clothed and fed, the younger ones to be educated and trained at an occupation. Washington did not own and could not emancipate the "dower slaves" at Mount Vernon.

Washington's failure to act publicly upon his growing private misgivings about slavery during his lifetime is seen by some historians as a tragically missed opportunity. One major reason Washington did not emancipate his slaves earlier was because his economic well-being depended on the institution. To circumvent this problem, in 1794 he quietly sought to sell off his western lands and lease his outlying farms in order to finance the emancipation of his slaves, but this plan fell through because enough buyers and renters could not be found. In the public arena, some historians including Twohig argue that he was reluctant to speak out against slavery because he did not wish to risk splitting apart the young republic over what was already a sensitive and divisive issue.

Religious beliefs

Washington's religious views are a matter of some controversy. There is considerable evidence that indicates he, like numerous other men of his time, was a Deist—believing in God but not believing in revelation or miracles. As a young man before the Revolution, when the Church of England was still the state religion in Virginia, he served as a vestryman (lay officer) for his local church. He spoke often of the value of prayer, righteousness, and seeking and offering thanks for the "blessings of Heaven". He sometimes accompanied his wife to Christian church services; however, there is no record of his ever becoming a communicant in any Christian church, and he would regularly leave services before communion—with the other non-communicants. When Rev. Dr. James Abercrombie, rector of St. Peter's Episcopal Church in Philadelphia, mentioned in a weekly sermon that those in elevated stations set an unhappy example by leaving at communion, Washington ceased attending at all on communion Sundays. Long after Washington died, when asked about Washington's beliefs, Abercrombie replied: "Sir, Washington was a Deist!" Various prayers said to have been composed by him in his later life are highly edited. He did not ask for any clergy on his deathbed, though one was available. His funeral services were those of the Freemasons at the request of his wife, Martha.

Washington was an early supporter of religious pluralism. In 1775, he ordered that his troops should not burn the pope in effigy on Guy Fawkes Night. In 1790, he published a letter written to Jewish leaders in which he envisioned a country "which gives to bigotry no sanction, to persecution no assistance . . . May the Children of the Stock of Abraham, who dwell in this land, continue to merit and enjoy the good will of the other Inhabitants; while every one shall sit under his own vine and fig tree, and there shall be none to make him afraid."

Myths and misconceptions

- An early biographer, Parson Weems, was the source of the famous fable about young Washington cutting down a cherry tree.

- A popular belief is that Washington wore a wig, as was the fashion among some at the time. He did not wear a wig; he did, however, powder his hair, as represented in several portraits, including the well-known unfinished Gilbert Stuart depiction.

- One famous story about Washington has him throwing a silver dollar across the Potomac River. He may have thrown an object across the Rappahannock River, the river on which his childhood home, Ferry Farm, stood. However, the Potomac is over a mile wide at Mount Vernon.

- Washington's teeth were not made out of wood, as was once commonly believed. They were made out of teeth from different kinds of animals, specifically elk, hippopotamus, and human. One set of false teeth that he had weighed almost four ounces (110 g) and were made out of lead.

Notes

- Dorothy Twohig, "The Making of George Washington", in Warren R. Hofstra, ed., George Washington and the Virginia Backcountry (Madison, 1998).

- This account of Washington in the French and Indian War follows the major scholarly biographies by Freeman, Flexner, Ferling, Ellis, and Lengel. Because of his ambition, provincialism, and military blunders, some scholars have found Washington at this time to be somewhat unsympathetic; for works particularly critical of Washington during this era, see Bernhard Knollenberg, George Washington: The Virginia Period, 1732–1775 (Duke University Press, 1964) and Thomas A. Lewis, For King and Country: The Maturing of George Washington, 1748–1760 (New York, 1992). For an overall view on the French and Indian War which prominently features Washington, see Fred Anderson, Crucible of War: The Seven Years' War and the Fate of Empire in British North America, 1754–1766 (New York, 2000).

- John K. Amory, M.D., "George Washington’s infertility: Why was the father of our country never a father?" Fertility and Sterility, Vol. 81, No. 3, March 2004. [http://www.asrm.org/Professionals/Fertility&Sterility/georgewashington.pdf (online, PDF format)

- Joseph Ellis, His Excellency, George Washington, p. 70.

- George Washington Papers at the Library of Congress, 1741-1799: Series 3b Varick Transcripts. Library of Congress. Accessed on May 22, 2006.

- The earliest known image in which Washington is identified as such is on the cover of the circa 1778 Pennsylvania German almanac (Lancaster: Gedruckt bey Francis Bailey). This identifies Washington as "Landes Vater" or Father of the Land.

- Number of slaves: Henry Wiencek, An Imperfect God: George Washington, His Slaves, and the Creation of America, p. 46; Ellis, pp. 262–63. Quotes from visitors to Mount Vernon: John Ferling, The First of Men, p. 476.

- Slave raffle linked to Washington's reassessment of slavery: Wiencek, pp. 135–36, 178–88. Washington's decision to stop selling slaves: Fritz Hirschfeld, George Washington and Slavery: A Documentary Portrayal, p. 16. Influence of war and Wheatley: Wiencek, ch 6. Dilemma of selling slaves: Wiencek, p. 230; Ellis, pp. 164–7; Hirschfeld, pp. 27–29.

- Quotes and Lafayette plans: Dorothy Twohig, "'That Species of Property': Washington's Role in the Controversy over Slavery", in Don Higginbotham, ed., George Washington Reconsidered (University Press of Virginia, 2001), pp. 121–22.

- Washington's slaves in Philadelphia and the scheme to rotate them: Wiencek, ch. 9; Hirschfeld, pp. 187–88; Ferling, p. 479.

- Twohig, "That Species of Property", pp. 127–28.

- Letter to the Hebrew Congregation in Newport, 1790 . This letter may have been ghostwritten by Thomas Jefferson, Ellis, p. 195.

- Gilbert Stuart depiction

References

- Ellis, Joseph J. His Excellency: George Washington. New York: Knopf, 2004. ISBN 1400040310. Acclaimed interpretation of Washington's career.

- Ferling, John E. The First of Men: A Life of George Washington (1989). Biography from a leading scholar.

- Fischer, David Hackett. Washington's Crossing. (2004), prize-winning military history focused on 1775-1776.

- Flexner, James Thomas. Washington: The Indispensable Man. Boston: Little, Brown, 1974. ISBN 0316286168 (1994 reissue). Single-volume condensation of Flexner's popular four-volume biography.

- Freeman, Douglas S. George Washington: A Biography. 7 volumes, 1948–1957. The standard scholarly biography, winner of the Pulitzer Prize. A single-volume abridgement by Richard Harwell is available.

- Higginbotham, Don, ed. George Washington Reconsidered (2001).

- Hirschfeld, Fritz. George Washington and Slavery: A Documentary Portrayal. University of Missouri Press, 1997.

- Hofstra, Warren R., ed. George Washington and the Virginia Backcountry. Madison House, 1998. Essays on Washington's formative years.

- Lengel, Edward G. General George Washington: A Military Life. New York: Random House, 2005. ISBN 1400060818.

- Wiencek, Henry. An Imperfect God: George Washington, His Slaves, and the Creation of America. (2003).

Further reading

The literature on George Washington is immense. The Library of Congress has a comprehensive bibliography online. Notable works not listed above include:

- Elkins, Stanley M. and Eric McKitrick. The Age of Federalism. (1994) the leading scholarly history of the 1790s.

- Grizzard, Frank E., Jr. George! A Guide to All Things Washington. Buena Vista and Charlottesville, VA: Mariner Publishing. 2005. ISBN 0-9768238-0-2. Grizzard is a leading scholar of Washington.

- Grizzard, Frank E., Jr. The Ways of Providence: Religion and George Washington. Buena Vista and Charlottesville, VA: Mariner Publishing. 2005. ISBN 0-9768238-1-0.

- McDonald, Forrest. The Presidency of George Washington. 1988. Intellectual history showing Washington as exemplar of republicanism.

- Peterson, Barbara Bennett. George Washington: America's Moral Exemplar, 2005.

- Washington, George and Marvin Kitman. George Washington's Expense Account. Grove Press. (2001) ISBN 0-8021-3773-3 Account pages, with added humor.

External links

- George Washington and Deism

- George Washington: A Life -- first chapter of the biography by Willard Sterne Randall

- George Washington for Kids

- George Washington Quotes at Liberty-Tree.ca

- 39 Volume Collection of the Works of George Washington

- Papers of Washington Full versions on-line from the University of Virginia

- Papers of Washington Avalon Project (incl. Inaugural Addresses, State of the Union Messages, and more)

- Armigerous American Presidents Series

- Library of Congress: Washington's Commission as Commander in Chief

- Biography of George Washington

- George and Martha Washington Marriage Profile

- A pedigree of George Washington

- George Washington Genealogy on Wikicities

- Teaching about George Washington

- The First Presidential Veto Analysis of the first veto by a U.S. President

- General Washington's military rank

- Fact File and Biography of George Washington

- White House Biography

- Works by George Washington at Project Gutenberg

- George Washington: Archontology.org, chronology, dates, terms, election results

- George Washington historic sites in Virginia - Official Tourism Website

| Preceded by(none) | Federalist Party presidential candidate 1789 (won), 1792 (won) |

Succeeded byJohn Adams |

| Preceded by(none) - Cyrus Griffin was President of the Continental Congress | President of the United States April 30 1789 – March 3 1797 |

Succeeded byJohn Adams |

| Preceded byJames Wilkinson | Senior Officer of the United States Army 1798-1799 |

Succeeded byAlexander Hamilton |

Template:Link FA Template:Link FA

Categories:- 1732 births

- 1799 deaths

- American Episcopalians

- American Freemasons

- American surveyors

- Autodidacts

- Continental Army generals

- Continental Congressmen

- English Americans

- Founding Fathers of the United States

- French and Indian War people

- George Washington

- People from Virginia

- Presidents of the United States

- Revolutionaries

- Scottish-Americans

- Signers of the United States Constitution

- Slaveholders

- United States presidential candidates