This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Keith-264 (talk | contribs) at 17:27, 15 June 2014 (→top: Expanding article). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 17:27, 15 June 2014 by Keith-264 (talk | contribs) (→top: Expanding article)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)| Battle of Le Mesnil-Patry | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Battle for Caen | |||||||

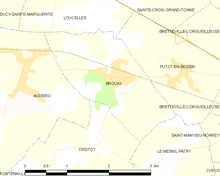

Map of Le Mesnil-Patry and Cristot (commune FR insee code 14205.png) | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

The Queen's Own Rifles of Canada 1st Hussars | 12th SS Panzer Division | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

116 dead or missing 35 wounded 22 captured, 51 tanks | 189, 3–14 Panther tanks | ||||||

| Operation Overlord (Battle of Normandy) | |

|---|---|

Prelude

Airborne assault Normandy landings Anglo-Canadian Sector Logistics Ground campaign Anglo-Canadian Sector

Breakout

Air and Sea operations Supporting operations

Aftermath |

The Battle of Le Mesnil-Patry was the last big operation conducted by Canadian land forces in Normandy during June 1944. The Queen's Own Rifles of Canada in the 8th Canadian Infantry Brigade of the 3rd Canadian Division, supported by the 6th Canadian Armoured Regiment (1st Hussars) of the 2nd Canadian Armoured Brigade attempted to take the village of Le Mesnil-Patry in Normandy. The attack was a southward advance west of Cheux, towards the high ground of Hill 107, during attacks by the 50th (Northumbrian) Infantry Division and the 7th Armoured Division intended to capture the city of Caen and to advance in the centre of the bridgehead next to the US First Army. The battle was a German defensive success but the greater German objective of defeating the invasion by a counter-offensive also failed.

Both sides changed tactics after the first week of the invasion, the Germans resorted to defence-in-depth and limited counter-attacks, to slow the Allied advance inland and avoid casualties and losses of equipment until reinforcements arrived. The Allies began to accumulate supplies to conduct attrition attacks, rather than persist with mobile operations by large numbers of tanks supported by infantry. More atrocities by troops of the Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) against Canadian prisoners occurred and orders were given by a junior Canadian commander to refrain from taking German prisoners in reprisal, although this was countermanded by higher authority as soon as it was discovered. Offensive operations in the area of the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division ceased apart from raiding and reconnaissance patrols, until VIII Corps commenced Operation Epsom on 26 June.

Background

On 6 June 1944, Allied forces invaded France by launching Operation Neptune, the beach landing operation of Operation Overlord. A force of several thousand ships assaulted the beaches in Normandy, supported by approximately 3,000 aircraft. The D-Day landings were generally successful but the Allied forces were unable to take Caen as planned.

In addition to seaborne landings, the Allies also employed Airborne forces. The U.S. 101st and 82nd Airborne Divisions, as well as the British 6th Airborne Division (with an attached Canadian airborne battalion), were inserted behind the enemy lines. The British and Canadian paratroopers behind Sword Beach were to occupy strategically important bridges such as Horsa and Pegasus, as well as to take the artillery battery at Merville in order to hinder the forward progress of the German forces. They managed to establish a bridgehead north of Caen on the east bank of the Orne, that the Allied troops could use to their advantage in the battle for Caen.

Prelude

Plan

On 10 June plans were laid for an attack by the 2nd Canadian Armoured Brigade south of Norrey-en-Bessin, to occupy the Mue valley in support of the main attack due on 12 June. Early on 11 June the attack was cancelled by Dempsey and replaced by an attack as the left pincer of another attempt to capture high ground south of Cristot, as the 69th Infantry Brigade of the 50th (Northumbrian) Division, attacked further west near Bronay. An attack by the 7th Armoured Division through Tilly-sur-Seulles on Villers-Bocage and Évrecy, required that all German units further east be engaged to prevent them moving westwards. At 8:00 a.m. the 6th Armoured Regiment was told to attack at 1:00 p.m., the short notice leaving little time to prepare, particularly the arrangements for reconnaissance and artillery support.

The 1st Hussars of the 6th Armoured Regiment and The Queen's Own Rifles of Canada were to attack Norrey-en-Bessin and then advance 2 miles (3.2 km) south, to capture high ground near Cheux, with B Squadron attacking first followed by C, the Headquarters squadron and then A Squadron. The infantry were to ride on the tanks and in the first phase reach Le Mesnil-Patry by 1:00 p.m. and then a right flanking movement through the village was to bypass Cheux; the rest of the armoured brigade was then to join the 6th Armoured Regiment on the objective. The commanders of the first phase asked for more time to prepare but were refused because of the importance of the attacks by the 7th Armoured and 50th (Northumbrian) Infantry divisions. A successful attack by the Canadians could force the Germans out of Cristot and ease the advance of the 50th Division.

Battle

Le Mesnil-Patry

The Canadian column reached Norrey-en-Bessin at 2:00 p.m. to find that the Canadian troops there had not been informed of the attack and that the proposed forming up place was in a minefield. The flat grain fields towards Le Mesnil-Patry had not been occupied and no evidence had appeared to indicate a German withdrawal. German artillery and mortar fire began on the village as the attackers moved through the village streets and formed up. The advance through the fields between Norrey and Le Mesnil-Patry was intended to begin at the same time the British attack further west against Cristot but this was delayed. B Squadron of the 1st Hussars took the lead, with men of D Company of the Queen's Own Rifles riding on the tanks.

SS-Panzergrenadier Regiment 26 and a company of tanks from the 12th SS-Panzer Division were able to ambush the tanks of B Squadron in the grain fields near Le Mesnil Patry, in part due to intelligence gleaned from Hussars radio traffic, after capturing wireless codes from a destroyed Canadian tank on 9 June. Mortar and machine-gun fire forced the infantry to dismount to engage the German infantry and the tanks of B Squadron pushed on, scattering German infantry in their path. Some B Squadron tanks and infantry reached a small rise on the edge of the village, where the tanks were engaged by concealed anti-tank guns on the left flank near St. Mauvieu, which quickly knocked out six tanks. C Squadron moved to the right to give covering fire but were mistakenly engaged by British anti-tank guns of the 50th Division. C Squadron retired, flying recognition signals and had to pick its way round the Canadian minefields and the ruins of Norrey, where the German artillery had collapsed the church into the road.

B Squadron entered Le Mesnil-Patry, where three German tanks attacked from the right flank and knocked out the Canadian tanks which had taken position in an orchard. The German and Canadian infantry took cover from the cross-fire as tanks on both sides were knocked out. The commander of the first Sherman saw that the German troops and tanks in the area were formed up for attack, three half-tracks parked together and infantry running around in confusion and then about thirty tanks also parked together, a battery of 88mm guns and more half-tracks. Three of the half-tracks were destroyed and the Sherman set on fire. The crew reversed for 600 yards (550 m), with clothes and ammunition burning on the outside of the tank, as German Panzergrenadiers threw grenades and the crew fired back, before baling out and retiring along a ditch. Major E. Dalton, commander of the most advanced section of the Queen's Own Rifles, was wounded in the leg by mortar fire and Lieutenant-Colonel Colwell, the commander of the Hussars, who was with the advanced group, ordered a withdrawal to the start-line. B Squadron was trapped in the village and almost destroyed; using Panzerfausts, Panzerschrecks and anti-tank guns, the Germans knocked out 37–51 Sherman tanks, only two of which returned.

In the evening the artillery-fire diminished, several ambulances drove out from the Canadian lines and the Germans ceased fire as wounded were collected by both sides. The Canadians claimed 14 Panthers destroyed and during the night, the Fort Garry Horse and the infantry of the Chaudières concentrated between Bray and Rots, about 3 miles (4.8 km) behind the front line, to forestall any attempt by the Germans to exploit the confusion and attack towards the coast. A Chaudière patrol into Rots was allowed to approach unhindered, until at close range and then fired on, only a few wounded returning. Later on the 46th Royal Marine Commando attacked the village during the night and after dawn the Chaudières searched the village for ambush parties and found it strewn with Commando and SS dead.

Cristot

The 69th Brigade attack on Cristot began from Audrieu to the north-west, to guard the left flank of the 8th Armoured Brigade and the 8th Battalion, Durham Light Infantry in St. Pierre. The 5th East Yorks would then relieve the 1st Dorsets on the high ground of Point 103, which would also keep the eastern (left) flank of the 50th (Northumbrian) Division level with the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division and would then capture the high ground at Point 102, south of Cristot. The attack was arranged very quickly and very little was known about the ground, beyond what the commander of the 8th Armoured Brigade had learned during the morning, that only scattered German infantry were in the area. It was suspected that the Germans were under cover, waiting for the main attack before revealing themselves. The brigade plan was for an attack with the 6th and 7th Green Howards forward and for the 5th East Yorks to move on Point 103, supported by the 4/7 Royal Dragoon Guards and artillery from the 147th Field Regiment and two batteries of the 90th Field Regiment but a detailed fire plan could not be arranged.

The attack was begun at 2:30 p.m. by the 6th Green Howards and the tanks but Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) (12th SS-Reconnaissance Battalion) had arrived around Cristot earlier in the day. During the advance through dense bocage, the tanks and the infantry became separated near Cristot, at about 5:00 p.m. The Germans let the unescorted British armor to pass by and then quickly knocked out seven of the nine tanks from the rear; by 6:00 p.m., the 6th Green Howards advance had also been stopped outside Cristot. The reserve company was sent forward and began to force back the German defenders but parties of German infantry began to infiltrate the 6th Green Howards. By 8:30 p.m. the 6th Battalion had nearly reached Point 102, despite many casualties. It was then learned that a German armoured force was attacking across the 6th Battalion axis of advance and a retreat was ordered westwards to the high ground of Point 103 to avoid encirclement.

Aftermath

Analysis

The attack on Le Mesnil-Patry had been disastrous for the Canadian attackers and the broader Allied advance on Caen was defeated, The 7th Green Howards advance from the west also failed, as the battalion was stopped by machine-gun fire along the Bayeux–Caen railway embankment near Brouay. The 5th East Yorks were caught in the open, when moving to relieve the 1st Dorsets, during the preparatory artillery bombardment for a German counter-attack on Point 103 and had many casualties. The 6th Green Howards may have disrupted the German infantry forming for the attack on Point 103 but the German tanks overran the positions of the 5th East Yorks. Having also become separated from their infantry, the German tanks were repulsed at the firm base held by the 1st Dorsets and part of the 8th Armoured Brigade at 10:30 p.m.

The attack on Cristot had been planned according to the January 1944, 21st Army Group infantry-tank theory, in which an attack was to be made in waves, with tanks followed by infantry and then more tanks. Experience showed that in close country, tanks must attack side by side with the infantry and even then casualties for tanks and infantry would be high as it was extremely difficult for tanks to watch accompanying infantry. The attempts by XXX Corps to advance round the open German flank at Caumont and the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division to capture high ground around Le Mesnil-Patry, with tank forces supported by infantry rather than vice-versa, were not tried again until Operation Goodwood, having experienced similar losses to those of the 12th SS-Panzer Division during the first few days; the Anglo-Canadians began to accumulate resources to conduct set-piece attrition attacks. The German attacks had also failed; the 12th SS-Panzer Division operation order of 7 June, required the division to throw the Allies into the sea but the attempt had also been a costly failure. The Germans changed tactics and began to limit counter-attacks to restore a defence in depth, rather than continue the costly failed counter-offensive against the invasion.

Casualties

D Company of the Queen's Own had 96 casualties, most listed as missing. During the day 80 men of the 6th Armoured Regiment and 99 men of the Queen's Own Rifles were lost. In 1997 McNorgan recorded 148 Canadian and 189 German casualties and three German tanks knocked out. The defence of Cristot cost Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) c. 70 and the 6th Green Howards 250 casualties. When the fighting in the area diminished after 14 June, Sergeant Gariepy, the commander of the B Squadron tank which had escaped from Le Mesnil-Patry and the 1st Hussar padre went out to identify the dead and recover identity discs. A few days after the Canadian attack, more than 2,400 German dead were found on the battlefield, although this appears to be an exaggeration.

Atrocities

Men of the Headquarters Company of the Queen's Own Rifles were ordered to search for Canadian dead, before the Canadians withdrew completely from the area. Amongst them was Bill Bettridge, who discovered 6 Queen's Own Riflemen from D Company, who all had the same wound. Bettridge later wrote that

After the tanks retreated from there, the Germans got up and started searching for anybody that was still alive and they just put a bullet through all their heads so the six of them were all killed, all murdered.

following the action at Le Mesnil-Patry, troops of the 12th SS-Panzer Division captured seven Canadians, who had been wandering around no-man's land since the battle, all being tired and hungry. The men were interrogated by an officer of the 12th SS-Engineering Battalion at an ad-hoc headquarters in the village of Mouen, about 5 miles (8.0 km) south-east of Le Mesnil-Patry. On 14 June, two crew members of the 1st Hussars reached Canadian lines and reported that they had seen that several Canadians had been shot in the back after surrendering. A Canadian 1st Army inquest Report of the Court of Inquiry Re: The Shooting of Prisoners of War by German Armed Forces at Mouen, Calvados, Normandy, 17 June 1944, the men were

- B49476 - Trooper Perry, C.G. - Canadian Armoured Corps

- B43258 - Serjeant McLaughlin, T. C. - Queen's Own Rifles of Canada

- ?????? - Rifleman Campbell, J.R. - Queen's Own Rifles of Canada

- B138240 - Rifleman Willett, G.L. - Queen's Own Rifles of Canada

- B138453 - Rifleman Cranfield, E. - Queen's Own Rifles of Canada

- B144191 - Corporal Cook, E. - Queen's Own Rifles of Canada

- B42653 - Rifleman Bullock, P. - Queen's Own Rifles of Canada

At c. 10:00 p.m., the men had been led to the outskirts of the village under armed guard. Cook, Cranfield, Perry and Willett were killed by a firing squad and the remaining men were shot in the head at close-range. In the Canadian 1st Army report it was concluded

That all the above named soldiers were murdered by the German armed forces in violation of the well recognised laws and usages of war and the terms of the Geneva Convention of 1929. That the above named soldiers were at the time of their deaths prisoners of war and entitled to treatment as such. That the soldiers were, on the date of their deaths, in the custody of a detachment of the 12th SS Panzer Engineer Battalion, probably the Third Company of that battalion. That the commanding officer of the said battalion was a certain Sturmbanfuhrer ("Major") Muller, but there is no evidence whether the Headquarters of the battalion or its commanding officer were present in Mouen on the date of the incident. That one or more of the officers or NCO's of the said battalion were responsible for the murder of the said Canadian Soldiers. That fourteen German soldiers who escorted the said Canadian soldiers to the place where they were murdered, and whose names, with one exception, are at present unknown to the Court, are equally implicated with their officers or NCO's in the said murder. The exception referred to is SS. Mann Alfred Friedrich, now deceased.

the SS made the local French villagers dig a mass grave and bury the men, which was discovered by troops of the 49th (West Riding) Division when they captured the village on 25 June. No-one from the 12th SS-Panzer Division was prosecuted for the crime. Stories of German atrocities circulated swiftly among Canadian troops and an order-of-the-day instructed the Canadians to take no prisoners, until quickly countermanded by higher authority.

References

- Ford 2004, pp. 90, 96.

- Keegan 1989, p. 143.

- Scarfe 1947, p. 18.

- Stacey 1960, p. 139.

- ^ Stacey 1960, p. 140.

- Copp 2003, p. 75.

- Copp 2003, p. 76.

- McKee 1964, p. 98.

- McKee 1964, p. 99.

- Martin & Whitsed 2008, p. 20.

- Stacey 1960, p. 141.

- ^ McKee 1964, p. 100.

- ^ Stark 1951.

- Ellis 1962, p. 253.

- Williams 2007, p. 70.

- Williams 2007, p. 71.

- ^ Williams 2007, p. 72.

- Reid 2005, pp. 39–40.

- Copp 2003, pp. 256–257.

- McNorgan 1997.

- McKee 1964, p. 103.

- McKee 1964, p. 102.

- Margolian 1998, p. 123.

- McKee 1964, pp. 102–103.

Bibliography

- Books

- Copp, T. (2003). Fields of Fire: The Canadians in Normandy. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0-8020-3780-1. OCLC 56329119.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Ellis, Major L. F.; with Allen R. N., Captain G. R. G. Allen; Warhurst, Lieutenant-Colonel A. E.; Robb, Air Chief-Marshal Sir J. (1962). Butler, J. R. M. (ed.). Victory in the West: The Battle of Normandy. History of the Second World War: United Kingdom Military Series. Vol. I (Naval & Military Press 2004 ed.). London: HMSO. ISBN 1-84574-058-0.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - Ford, Ken (2004). Sword Beach. Battle Zone Normandy. Sutton Publishing. ISBN 0-7509-3019-5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Keegan, J. (1989). The Times Atlas of the Second World War (Crescent Books 1995 ed.). London: Times Books. ISBN 0-51712-377-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Margolian, H. (1998). Conduct unbecoming: the Story of the Murder of Canadian Prisoners of War in Normandy. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0-80204-213-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Martin, C. C.; Whitsed, R. (2008). Battle Diary: From D-Day and Normandy to the Zuider Zee and VE. Toronto: Dundurn Press. ISBN 1-55488-092-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - McKee, A. (1964). Caen: Anvil of Victory (Pan, 1972 ed.). London: Souvenir Press. ISBN 0-330-23368-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Reid, B. A. (2005). No Holding Back: Operation Totalize, Normandy, August 1944. Toronto: Robin Brass Studio. ISBN 1-896941-40-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Scarfe, Norman (2006) . Assault Division: A History of the 3rd Division from the Invasion of Normandy to the Surrender of Germany. Stroud, Gloucestershire: Spellmount. ISBN 1-86227-338-3.

- Stacey, Colonel C. P. (1960). The Victory Campaign: The operations in North-West Europe 1944–1945 (PDF). Official History of the Canadian Army in the Second World War. Vol. III. Ottawa: The Queen's Printer and Controller of Stationery. OCLC 606015967. Retrieved 14 June 2014.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link)

- Theses

- Williams, E. R. (2007). 50 Div in Normandy: A Critical Analysis of the British 50th (Northumbrian) Division on D-Day and in the Battle of Normandy (MMAS). Fort Leavenworth KS: Army Command and General Staff College. OCLC 832005669. Retrieved 15 June 2014.

{{cite thesis}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link)

- Websites

- McNorgan, M. R. (1997). "Debacle in Normandy, Le Mesnil-Patry, 11 June 1944". Steel Chariots: A Resource Site for the Canadian Armour Enthusiast. Retrieved 15 June 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Stark, F. (2009) . "A History of the First Hussars Regiment, 6–11 June, part II". War Chronicle. Retrieved 15 June 2014.

Further reading

- Lackenbauer, P. W. (2001). "Kurt Meyer, 12th SS Panzer Division and the Murder of Canadian Prisoners of War in Normandy: An Historical and Historiographical Appraisal". Gateway: An Academic History Journal on the Web. University of Saskatchewan. Retrieved 15 June 2014.

External links

| Primary articles on the Battle of Normandy, Western Front, World War II | |

|---|---|

| Operations |

|

| Battles |

|

| Landing points (W→E) | |

| Logistics |

|

| Gun batteries | |

| Other places | |

| See also |

|