This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Chief Inspector of Irish Iron Age (talk | contribs) at 23:14, 19 June 2014. The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 23:14, 19 June 2014 by Chief Inspector of Irish Iron Age (talk | contribs)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)

| This article is an orphan, as no other articles link to it. Please introduce links to this page from related articles; try the Find link tool for suggestions. (December 2013) |

The Chronicles of Eri is a collection of purported ancient Irish manuscripts which detail the history of Ireland, translated by Roger O'Connor in 1822.

Content

Roger O' Connor published the "Chronicles of Eri" in 1822. He originally proposed it as the 'Chronicles of Ulladh (Ulster)' as it purports to relate to the history of the ruling dynasty of that province. Roger O'Connor claimed direct descent from Ulster's ruling dynasty, recalled as the Er in the chronicles and Ir in Irish manuscripts. The chronicle was thus simply introduced as "by O'Connor" in keeping with an Irish tradition that the head of a clan need not employ his first name.

The Chronicles of Eri were published in two volumes, although the first formally assumes this title, it is referred to locally as the "Chronicles of Gaalag" (Galicia). This is represented by the concluding section of some 91 pages in volume 1. The remainder of this volume is a lengthy thesis containing O'Connor's own opinions and conjectures on history on the chronicle under a heading of "demonstration".

The chronicle of Gaalag breaks down into two significant parts. The first is attributed to Eolus, a king of Galicia who represents the oral traditions of history that he claims prevailed in his time. He claimed to have travelled to Sgadan (Sidon) where he learnt the art of writing from the Feine (Phoenicians). His account contains little detail, though it claims to allude to a series of earlier ages, starting with the original migration of Gaels out of the Indus valley following the "flood of Sgeind" thousands of years before his time. He claimed his forebears were the peoples now alluded to as Gutians and Hurrians; nomadic tribes who menaced the settled peoples of Mesopotamia, which the chronicle infers as enslaved populations. There is no agreement as to how the dates of these events were known to O’Connor in 1822.

The next Age is alleged to have followed Assyrian king Sargon's defeat of the nomadic Gaels, and their migration up the river Euphrates under their own king Noai, also alluded to as Er and Ard-fear. The chronicle contends this king led his people to safety near Mount Ararat where they settled calling the region of ard-mion (Armenia, literally high-mine). The chronicle infers that the predominance of the descendants of Noai (Biblical Noah) was due to their ability to work bronze which gave them superior weapons. The people are said to have flourished and extended their realm on all sides under Iath-foth, or Mac-Er, and his successor Og (Armenian Hayk). This part of the account was deemed disrespectful of the Biblical story of Noah, and was to upset many in O'Connor's time as the Old Testament was then seen as sacrosanct by many. There remains no accepted explanation as to how the dates inferred for Sargon and accorded to Hayk or Og should converge so closely on modern estimates.

Subsequently a descendant king named Glas was given the land of Ib-er (place of the Er, also called Tubhal, an area later known as Caucasian Iberia, not to be confused with Iberia or Spain) by his brother Dorca. Glas appears in Irish manuscripts as 'Goídel Glas', stories surrounding him converge loosely on the chronicle but with alternative overlays. The next chronicled Age was marked by the migration of Calma from Caucasian Kingdom of Iberia, to Galicia in Spanish Iberia in search of his comrades taken into bondage by Phoenicians to work the mines. Among his descendants was Eolus who claimed to be the first of dozens to leave a written record of his own times.

Following the death of Eolus the role of keeping the chronicle was assigned to an appointed secretary of the king known as Ard-ollamh. An embassy was sent by Don, successor to Eolus, to negotiate with the kings ruling over the Phoenicians, listed as Ramah then Amram then a second Ramah. There is no accepted theory as to how O’Connor around two centuries ago could have known the names and dates now ascribed to these Egyptian Pharaohs, or that they were overlords to the Phoenicians (confirmed by the Phoenician Amarna letters found in 1887, which date from around the time Eolus claimed to have learnt to write in Sidon). Amram was chronicled as having succeeded his uncle Ramah in 1350 BCE, the date now assumed by Egyptologists is 1341-32 BCE. Despite his records in the chronicle, Amun-ra is still formally said to have disappeared from history until the discovery of his tomb in 1922. The chronicle is unique in inferring these figures as kindred to the Gaels, it alleges that Ramases I ‘‘did send Ollamh to abide amongst the Geal in Gael-ag, and the teachers of Aoi-mag did give knowledge unto the nobles’’. In 2009 the unlikely sounding claim was supported by DNA tests on Amun-ra or Tutakamun (‘’the living image of Amun-ra’’) showing him to carry the Gaelic R1b1a2 haplogroup.

The accounts of the following three centuries were attributed to various ollamh's whose names are recalled in the chronicle. At this period there was little recorded by many as they complained their office was undermined by the powerful priests of Baal, chronicled as crom-fear, who were hostile to the secular writings of Eolus against them.

Volume one is concluded by what it claims were momentous events prompting the exodus to Ireland. Following a row with the Phoenicians, who were generally chronicled as representing Egyptian interests abroad, the Gaels were attacked by Sru or Hercules and the Gaelic king Golam slain in battle. The chronicle claimed an adage by which the Gaels lived was '’die or live free’’ so the remnant who had survived war or enslavement set sail for Ireland in the wake of Ith who had been killed there when scouting the land. Galician traditions concerning Breogán’s tower or the tower of Hercules follow the chronicle more closely than do Irish manuscripts, although only the chronicle claims that both of the tower’s names specifically recall the same story.

Up to this time there is little correspondence between the claims of Irish manuscripts and the chronicle, but from this period forward the chronicle follows much the same names and approximates the reign durations of pagan kings recalled in manuscripts. However manuscripts typically relate one or two lines for each king, whereas the chronicle affords many lengthy accounts. Manuscripts generally allude to Golam as Milesius or Mil Espaine (soldier of Spain).

Volume II claims to represent the history of Gaelic Ireland from its alleged beginning in 1006 B.C. The land was won from the Tuatha de Danaan who had invaded some two centuries earlier, victory going to the relatively small force of Gaels partly as a result of their superior weapons but mainly due to help from the natives (Fir-gneat) who the chronicle claims had been enslaved and abused by the Danaan. A treaty with the Danaan reserved for them the province of Connaught and Clare (west of the Shannon).

The accounts of the Irish era are generally more substantial than those of the Galician era, but relate only to the period as it was perceived in Ulster where the Ollamhs were reserved priority over the priests or crom-fear, who dominated the southern provinces. Many ollamhs return to a longstanding theme hostile to the priests, accusing them of corruption, and advancing their interests by promoting violence and ignorance among the people.

As might be expected at this point the chronicle becomes more insular, though occasional references are made to the outside world. For example in 914 BC Ithbaal, the high-priest (ard-cromfear) of Tyre is said to have succeeded and together with his daughter Ishbaal spread the practice of Baal worship through all Isreal and the collective nations. His embassy in Ireland attempted to reinforce the crom-fear with bribes to king Tigernmas, as the chronicle claims the corruption of these priests was a vehicle by which the Phoenicians extended their bronze mining and trading interests. The chronicled version of the story of Tigernmas and Crom Cruach, although challenging to conventions of the manuscripts, was lent support In 1923 when French archaeologist Pierre Montet, working in Jbeil, (historic Byblos) found the Ahiram sarcophagus, tentatively dated to around this period. Its Phoenician inscription starts: A coffin made (by) Ittobaal, son of Ahirom, king of Byblos. A little earlier in 1921 relics deemed to be Crom Cruach were found in Co.Cavan.

By far the most significant figure claimed of the Irish era was Eocaid Ollamh Fodhla of Ulster's line of Er, a reputed giant of his time (which allegedly concluded in 663 BC). On his appointment his close friend and Ollamh, Neartan said of him "in years a youth, in wisdom, aged is he". The chronicle maintains Ollamh Fodla unified the long feuding island by setting up a three yearly government assembly and games at Tara which were to become a focus of the chronicle from his time forward. He is credited with setting up the office of ‘Ard-righ’ (high king) and instituting Ireland's first formal legal code.

Centuries of relative peace are said to have flowed from Ollamh Fodla's institutions, though the level of inter-provincial feuding grows towards the close of the chronicle in 7 BC. The chronicle concludes abruptly with little hint as to the circumstances surrounding the end of all it claimed to represent. Irish manuscripts and tales from the Ulster cycle suggest that Conchorbar Mac Nessa's war with his cousin Fergus mac Róich was one possible cause. (Fergus was claimed by Roger O'Connor and others to have been his ancestor).

Contentions upon authenticity

The chronicle purports to represent centuries of written history long before the time of St. Patrick when it is widely believed that the formal alphabet first was introduced to Ireland, a primitive form of writing known as ogham is thought to have first emerged around a century earlier. Consequently the chronicle appears most implausible and has been dismissed as a fraud. Against all usual instincts, the belief that the chronicle of Eri must be a fraud has been called into question by a recent study.

The chronicle of Eri has never been the subject of a serious research paper by its critics. A series of often emotive charges has been directed against the chronicle, described by some sceptic’s as reviews. Common among these are fundamental errors which challenge their characterisation as ‘reviews’ rather than rants.

1) Language of the chronicle

One of the most widely cited reviews was by R A MacAlister , although he was not actually reviewing the chronicle, but rather another book premised upon it in the British-Israeli tradition.

O’Connor’s book title describes his scrolls as being in the ”Phoenician dialect of the Scythian language”. Little of his chronicle may be read without it being apparent that the language he awkwardly alludes to is Gaelic. The chronicle claims that Gaelic was spoken throughout Celtic Europe, this is now recognized by linguists who use Gaelic to interpret Celtic era place-names which are quite homogeneous over a large area of Europe, in line with classical claims of regional dialects of an essentially single Celtic language, now sometimes recalled as common Celtic. The chronicle claims Phoenician traders were not only able to understand this language, but that in fact it was them behind its spread. The old Gaelic for Gaelic is Bearla Feine or the Phoenician tongue.

Macalister takes O’Connor’s Phoenician dialect of the Scythian at face value, complaining of O’Connors ”blank incompetence to deal with the Phoenician histories of Eolus”. He was an authority on Hebrew and accuses O’Connor of making many spelling errors, citing the earlier noted Ard-mion (Armenia). Anyone taking a cursory look at the chronicle would soon see that it is originally in Gaelic from start to finish, and that the words depicted as spelling mistakes are presented as the Gaelic originals, each of which O’Connor carefully rendered in italics to distinguish them from the flow of his English translation.

2) Authorship of the chronicle

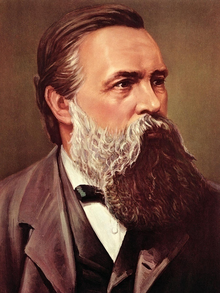

Frederick Engel’s in his History of Ireland of 1870 alleged the original manuscript is a verse chronicle chosen at will. The publisher is Arthur O'Connor. Arthur O’Connor was Roger’s brother. Engel’s muses how closely Roger’s son, the chartist leader Feargus O’Connor, resembles his uncle Arthur’s portrait in the front of the chronicle, (this of course being Roger).

Arthur O’Connor had personally organized the 1796 French invasion of Bantry Bay following his treaty with Lazare Hoche (In spite of common perceptions, Wolfe Tone was unable to attend this critical treaty at Angers, Arthur’s modern biographers concur that his real role in shaping Irish history was considerably more significant than the marginal memorials to him might suggest).

Various commentators follow Macalister who infers that the chronicles original author was only or principally Eolus in line with a similar claim made by the Quarterly review in 1832 (Vol 46, this review, like Macalister, was also addressed towards another related publication).

The Quarterly review admits it was written from an Anglo-Saxon perspective, the authors not altogether happy with the O’Connor brothers; leaders of United Irishmen who sought, and who may have succeeded in removing English rule from Ireland if what was called the worst storm in a century had not scattered the large French fleet carrying some 15,000 troops heading for Ireland and then pulled out the fraction of them that made it to Bantry bay back out to the Atlantic. At this time the British army was largely committed to engagements abroad, and the countries defense in the hands of informal militia groups, many hostile to the ruling oligarchy in Dublin Castle. At Bantry Bay circumstantial evidence suggests Roger O'Connor under the guise of leading signalman succeeded in supplying each French ship with a local harbour-pilot and in having this officially recorded as a tactical error.

Napoleon Bonaparte was an ally of the O'Connor brothers, he and his successors to the French executive rejected dissenting opinions in the fractured United Irish executive and accepted Arthur O’Connor’s claim to be its principal director so he was appointed to the position of General over Irish regiments in France. Roger O’Connor was the only member of the United Irish executive who managed to return to Ireland. Roger’s cousin Daunt recalls correspondence of 1811 from a library in Caen in which Napoleon raises his unconditional offer of troops to Ireland from 25 to 60 thousand if consultations with O’Connor suggested that sufficient numbers of the disaffected were still prepared to fight with him in Ireland. Roger O’Connor later claimed he acquired Dangan Castle from Napoleon’s enemy, the Duke of Wellington to recieve Napoleon when he arrived. Opposing Wellington at Battle of Waterloo was Marshal Grouchy, later uncle-in-law to Arthur O’Connor.

This background regarding Arthur was largely known at the time of the publication of the chronicle in 1822, Roger was widely suspected but the smallest extent of his activities was not proven. Circumstantial evidence suggests his undercover contributions to the Nationalist cause first as Captain Right and then ‘’Captain Rock’’ (Roger O’Connor, King) continues to elude history in large part due to a long series of calumniation’s directed against him, initially by his enemies in Dublin Castle and the house of Commons, and subsequently also the Catholic mainstream, in large part due to the deep offense admitted by ] (and his main source upon Roger, Father Crolly) to the highly secular views of both Roger and Arthur. Madden’s introduction illustrates the colours he uses to paint his portrait of Roger O’Connor: he might have served as a model mind for the Frankenstein creation of Mrs. Shelley's powerful imagination’... ‘he spent a large portion of that life forging lies, concocting deliberate schemes of imposture, and promulgating literary forgeries with a view of hurting the principles of Christianity. Research for Roger’s first biography In orbit of a local star(due for publication), suggests that each of the main allegations against his name is unsupportable by the lowest standards of today.

The O’Connor brothers had been schooled by Major Morris (who served in the British army in the American war of independence, but who worked under the cover of a feigned name for Washington). Both brothers had been to Trinity College, Dublin to study law. Lawyers from Trinity were to form a nucleus of the United Irish leadership. Enlightenment ideas and the American and French revolutions were foremost influences for the brother’s long fight for democracy in Ireland.

This background may help explain why the Quarterly review, along with other some early British reviewers were not naturally well disposed to O’Connor’s chronicle, primarily objecting to it on religious or Christian grounds in spite of the obvious issue that the chronicle concludes before the Christian era commences.

As noted above, the Galician king Eolus was the chronicle’s creator and first contributor, but not its sole or principle author; he was followed by many others, all of whom inferred their records were contemporary with the kings reigning during their employment as ard-ollamh. The writings attributed to Eolus comprise around 25 of the first 37 pages of the chronicle proper (O’Connor’s footnotes account for the difference). Before editing this page it read The contents (a lengthy 900 pages) are alleged to have been written by a Scythian chief called Eolus.

3) Content of the chronicle

The last quotation introduces a third common error recycled by critics. Much of the 900 pages alluded to above are O’Connor’s own demonstration; nowhere does he suggest this to be anything but his personal thesis. It is clearly separated away from the chronicle so it is not known why so many ‘reviewers’ should confuse O’Connor’s conjectures with the chronicle. The content of the chronicle does not feature prominently in commonly cited reviews of it, rather these tend to question O’Connor’s insights or conjectures which are inferred to represent part of the chronicle proper.

In defense of the critics alluded to above, none claim to have personally studied the chronicle, the fact that they were often reviewing related works and their tendency to recycle earlier misrepresentations of the chronicle suggests that some may have had little more knowledge of the chronicle than an earlier ‘review’. A claim is made in the academic press that the chronicle has been disproven, but an email request for detail has proved unsuccessful, and this information eludes the cited source.

Former support for the chronicle

Although now largely disregarded, there has been another series of reviewers defending the authenticity of the chronicle. They tend avoid the errors of its critics and show evidence of being acquainted with the work.

In July 1822, The Monthly magazine, introduced Mr. O’Connor’s work as “The most original and extraordinary which the printing press ever brought before the world”. They had little doubt about its integrity since included was a facsimile of one of the source scrolls The roll of the laws of Eri copied from the original MS.

James Roche, a prominent banker was described by Madden as an eminent literary man and historical antiquarian), he concludes that circumstantial evidence surrounding O’Connor’s claims dictates no foundation whatever for the charge made against him of attempting a literary fraud.

Scottish clergyman Peter H Waddell in 1875 published his work arguing for the authenticity of the Ossianic poems. He considered the Chronicles of Eri, forgotten or treated with, contempt as an imposture, but now capable of verification in all substantial respects. Waddell was unusual in demonstrating that the chronicle need not be seen as a threat to a minister of the gospel as he alludes to himself.

In the 1830’s a German version of the chronicle and was attended by a small flurry of publications premised on its authenticity. A century later another cluster of approving articles appeared in the German press in the wake of a book by L. Albert or Hermann which argued passionately for the case as is suggested by his book titles: Six Thousand Years of Gaelic Grandeur-unearthed. The most ancient and truthful chronicles of the Gael ... The Chronicles of Eri and later The Buried Alive Chronicles of Ireland; an open challenge to the Celtic scholars of Breo-tan and Eri. He concluded the war against the revelations of Eolus is not only a crime against truth, scientific honesty and the moral advancement of humanity, it must also be denounced as one of the most meaningless acts in the long history of human aberrations!. It seems possible his second work was never read by any of the scholars he was addressing as it currently is down to around 4 library copies worldwide.

The question of the chronicle’s placement here on wiki as a literary hoax is of some significance as the chronicle claims to double the course of Gaelic history. The question as to whether the chronicle is a fraud or not is a simple black and white, yes or no issue, at the heart of which lies the question of source scrolls.

Fraud

The Chronicles of Eri are widely now considered to be a literary fraud. O' Connor never revealed the ancient manuscripts he claimed to have translated and most believe they never existed. The archaeologist R. A. Stewart Macalister reviewed the work in 1941, calling it a clear fraud and its contents "cloud-cuckoo", comparing it to the Book of Mormon.

References

| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Chronicles of Eri" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (March 2014) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

- "Chronicles of Eri" vol 1 & 2 Roger O' Connor, Published by Sir Richard Philips and Co. 1822

- Monthly magazine or British Register vol 49 1820

- http://www.biography.com/people/king-tut-9512446#awesm=~oHCDdXwIQeZRYS

- Irish Historical Studies, Vol. 2, No. 7, Mar., 1941, pp. 335-337

- A life spent for Ireland W J O’Neill Daunt 1896 Later republished by Irish university press

- United Irishmen their lives and times, Richard R. Madden, Publisher J. Madden & Co. 1843

- Jane Hayter Hames Arthur O'Connor, United Irishman, Collins press 2001

- David P. Henige ‘Historical Evidence and Argument’ University of Wisconsin Press, 2005

- Joep Leerssen, ‘Remembrance and Imagination: Patterns in the Historical and Literary Representation of Ireland in the Nineteenth Century’ Cork University Press 1996

- Peter H. Waddell ‘Ossian and the Clyde’ J. Maclehose, 1875

- Die Schriften des Eolus und die Jahrbücher von Gaelag aus den Chronicles of Eri von O'Connor’. Wilhelm Gottlieb Levin von Donop 1838

- ‘Deutsche Urzeit’, and ‘Alteste und alte Zeit’ (1838)

- ‘Skytho-Gaalen in Orchomenos und Kyrene, Britannien und Irland’,(1834)

- ‘The magusanische Europe’, or ‘Phoenicians in the interior lands of Western Europe to the Weser and Werra’, (1830).

- "Remembrance and Imagination", Joseph Theodoor Leerssen, University of Notre Dame Press, 1997, p. 84f.

- Irish Historical Studies, Vol. 2, No. 7, Mar., 1941, pp. 335-337.

External links

- Fulltext at the Internet Archive