This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Mark v1.0 (talk | contribs) at 09:14, 2 October 2014 (→Medication). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 09:14, 2 October 2014 by Mark v1.0 (talk | contribs) (→Medication)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) For other uses, see Schizophrenia (disambiguation).Medical condition

| Schizophrenia | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Psychiatry, clinical psychology |

Schizophrenia (/ˌskɪtsˈfrɛniə/ or /ˌskɪtsˈfriːniə/) is a mental disorder often characterized by abnormal social behavior and failure to recognize what is real. Common symptoms include false beliefs, unclear or confused thinking, auditory hallucinations, reduced social engagement and emotional expression, and inactivity. Diagnosis is based on observed behavior and the person's reported experiences.

Genetics and early environment, as well as psychological and social processes, appear to be important contributory factors. Some recreational and prescription drugs appear to cause or worsen symptoms. The many possible combinations of symptoms have triggered debate about whether the diagnosis represents a single disorder or a number of separate syndromes. Despite the origin of the term from the Greek roots skhizein ("to split") and phrēn ("mind"), schizophrenia does not imply a "split personality", or "multiple personality disorder"—a condition with which it is often confused in public perception. Rather, the term means a "splitting of mental functions", reflecting the presentation of the illness.

The mainstay of treatment is antipsychotic medication, which primarily suppresses dopamine receptor activity. Counseling, job training and social rehabilitation are also important in treatment. In more serious cases—where there is risk to self or others—involuntary hospitalization may be necessary, although hospital stays are now shorter and less frequent than they once were.

Symptoms begin typically in young adulthood, and about 0.3–0.7% of people are affected during their lifetime. The disorder is thought to mainly affect the ability to think, but it also usually contributes to chronic problems with behavior and emotion. People with schizophrenia are likely to have additional conditions, including major depression and anxiety disorders; the lifetime occurrence of substance use disorder is almost 50%. Social problems, such as long-term unemployment, poverty, and homelessness are common. The average life expectancy of people with the disorder is ten to twenty five years less than the average life expectancy. This is the result of increased physical health problems and a higher suicide rate (about 5%).

Symptoms

Individuals with schizophrenia may experience hallucinations (most reported are hearing voices), delusions (often bizarre or persecutory in nature), and disorganized thinking and speech. The last may range from loss of train of thought, to sentences only loosely connected in meaning, to speech that is not understandable known as word salad in severe cases. Social withdrawal, sloppiness of dress and hygiene, and loss of motivation and judgment are all common in schizophrenia. There is often an observable pattern of emotional difficulty, for example lack of responsiveness. Impairment in social cognition is associated with schizophrenia, as are symptoms of paranoia. Social isolation commonly occurs. Difficulties in working and long-term memory, attention, executive functioning, and speed of processing also commonly occur. In one uncommon subtype, the person may be largely mute, remain motionless in bizarre postures, or exhibit purposeless agitation, all signs of catatonia. About 30 to 50% of people with schizophrenia fail to accept that they have an illness or their recommended treatment. Treatment may have some effect on insight. People with schizophrenia often find facial emotion perception to be difficult.

Positive and negative

Schizophrenia is often described in terms of positive and negative (or deficit) symptoms. Positive symptoms are those that most individuals do not normally experience but are present in people with schizophrenia. They can include delusions, disordered thoughts and speech, and tactile, auditory, visual, olfactory and gustatory hallucinations, typically regarded as manifestations of psychosis. Hallucinations are also typically related to the content of the delusional theme. Positive symptoms generally respond well to medication.

Negative symptoms are deficits of normal emotional responses or of other thought processes, and respond less well to medication. They commonly include flat expressions or little emotion, poverty of speech, inability to experience pleasure, lack of desire to form relationships, and lack of motivation. Negative symptoms appear to contribute more to poor quality of life, functional ability, and the burden on others than do positive symptoms. People with greater negative symptoms often have a history of poor adjustment before the onset of illness, and response to medication is often limited.

Onset

Late adolescence and early adulthood are peak periods for the onset of schizophrenia, critical years in a young adult's social and vocational development. In 40% of men and 23% of women diagnosed with schizophrenia, the condition manifested itself before the age of 19. To minimize the developmental disruption associated with schizophrenia, much work has recently been done to identify and treat the prodromal (pre-onset) phase of the illness, which has been detected up to 30 months before the onset of symptoms. Those who go on to develop schizophrenia may experience transient or self-limiting psychotic symptoms and the non-specific symptoms of social withdrawal, irritability, dysphoria, and clumsiness during the prodromal phase.

Causes

Main article: Causes of schizophreniaA combination of genetic and environmental factors play a role in the development of schizophrenia. People with a family history of schizophrenia who have a transient psychosis have a 20–40% chance of being diagnosed one year later.

Genetic

Estimates of heritability vary because of the difficulty in separating the effects of genetics and the environment; averages of 0.80 have been given. The greatest risk for developing schizophrenia is having a first-degree relative with the disease (risk is 6.5%); more than 40% of monozygotic twins of those with schizophrenia are also affected. If one parent is affected the risk is about 13% and if both are affected the risk is nearly 50%.

It is likely that many genes are involved, each of small effect and unknown transmission and expression. Many possible candidates have been proposed, including specific copy number variations, NOTCH4, and histone protein loci. A number of genome-wide associations such as zinc finger protein 804A have also been linked. There appears to be overlap in the genetics of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Evidence is emerging that the genetic architecture of schizophrenia involved both common and rare risk variation.

Assuming a hereditary basis, one question from evolutionary psychology is why genes that increase the likelihood of psychosis evolved, assuming the condition would have been maladaptive from an evolutionary point of view. One idea is that genes are involved in the evolution of language and human nature, but to date such ideas remain little more than hypothetical in nature.

Environment

Environmental factors associated with the development of schizophrenia include the living environment, drug use and prenatal stressors. Parenting style seems to have no major effect, although people with supportive parents do better than those with critical or hostile parents. Childhood trauma, separation from ones families, and being bullied or abused increase the risk of psychosis. Living in an urban environment during childhood or as an adult has consistently been found to increase the risk of schizophrenia by a factor of two, even after taking into account drug use, ethnic group, and size of social group. Other factors that play an important role include social isolation and immigration related to social adversity, racial discrimination, family dysfunction, unemployment, and poor housing conditions.

Substance use

About half of those with schizophrenia use drugs or alcohol excessively. Amphetamine, cocaine, and to a lesser extent alcohol, can result in psychosis that presents very similarly to schizophrenia. Although it is not generally believed to be a cause of the illness, people with schizophrenia use nicotine at much greater rates than the general population.

Alcohol abuse can occasionally cause the development of a chronic substance-induced psychotic disorder via a kindling mechanism. Alcohol use is not associated with an earlier onset of psychosis.

A significant proportion of people with schizophrenia use cannabis to help cope with its symptoms. Cannabis can be a contributory factor in schizophrenia, but cannot cause it alone; its use is neither necessary nor sufficient for development of any form of psychosis. Early exposure of the developing brain to cannabis increases the risk of schizophrenia, although the size of the increased risk is difficult to quantify; only a small proportion of early cannabis recreational users go on to develop any schizoaffective disorder in adult life, and the increased risk may require the presence of certain genes within an individual or may be related to preexisting psychopathology. Higher dosage and greater frequency of use are indicators of increased risk of chronic psychoses. Tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and cannabidiol (CBD) produce opposing effects; CBD has antipsychotic and neuroprotective properties and counteracts negative effects of THC.

Other drugs may be used only as coping mechanisms by individuals who have schizophrenia to deal with depression, anxiety, boredom, and loneliness.

Developmental factors

Factors such as hypoxia and infection, or stress and malnutrition in the mother during fetal development, may result in a slight increase in the risk of schizophrenia later in life. People diagnosed with schizophrenia are more likely to have been born in winter or spring (at least in the northern hemisphere), which may be a result of increased rates of viral exposures in utero. The increased risk is about 5 to 8%.

Mechanisms

Main article: Mechanisms of schizophreniaA number of attempts have been made to explain the link between altered brain function and schizophrenia. One of the most common is the dopamine hypothesis, which attributes psychosis to the mind's faulty interpretation of the misfiring of dopaminergic neurons.

Psychological

Many psychological mechanisms have been implicated in the development and maintenance of schizophrenia. Cognitive biases have been identified in those with the diagnosis or those at risk, especially when under stress or in confusing situations. Some cognitive features may reflect global neurocognitive deficits such as memory loss, while others may be related to particular issues and experiences.

Despite a demonstrated appearance of blunted effect, recent findings indicate that many individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia are emotionally responsive, particularly to stressful or negative stimuli, and that such sensitivity may cause vulnerability to symptoms or to the disorder. Some evidence suggests that the content of delusional beliefs and psychotic experiences can reflect emotional causes of the disorder, and that how a person interprets such experiences can influence symptomatology. The use of "safety behaviors" to avoid imagined threats may contribute to the chronicity of delusions. Further evidence for the role of psychological mechanisms comes from the effects of psychotherapies on symptoms of schizophrenia.

Neurological

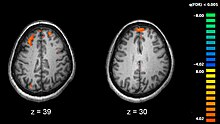

Schizophrenia is associated with subtle differences in brain structures, found in 40 to 50% of cases, and in brain chemistry during acute psychotic states. Studies using neuropsychological tests and brain imaging technologies such as fMRI and PET to examine functional differences in brain activity have shown that differences seem to most commonly occur in the frontal lobes, hippocampus and temporal lobes. Reductions in brain volume, smaller than those found in Alzheimer's disease, have been reported in areas of the frontal cortex and temporal lobes. It is uncertain whether these volumetric changes are progressive or preexist prior to the onset of the disease. These differences have been linked to the neurocognitive deficits often associated with schizophrenia. Because neural circuits are altered, it has alternatively been suggested that schizophrenia should be thought of as a collection of neurodevelopmental disorders. There has been debate on whether treatment with antipsychotics can itself cause reduction of brain volume.

Particular attention has been paid to the function of dopamine in the mesolimbic pathway of the brain. This focus largely resulted from the accidental finding that phenothiazine drugs, which block dopamine function, could reduce psychotic symptoms. It is also supported by the fact that amphetamines, which trigger the release of dopamine, may exacerbate the psychotic symptoms in schizophrenia. The influential dopamine hypothesis of schizophrenia proposed that excessive activation of D2 receptors was the cause of (the positive symptoms of) schizophrenia. Although postulated for about 20 years based on the D2 blockade effect common to all antipsychotics, it was not until the mid-1990s that PET and SPET imaging studies provided supporting evidence. The dopamine hypothesis is now thought to be simplistic, partly because newer antipsychotic medication (atypical antipsychotic medication) can be just as effective as older medication (typical antipsychotic medication), but also affects serotonin function and may have slightly less of a dopamine blocking effect.

Interest has also focused on the neurotransmitter glutamate and the reduced function of the NMDA glutamate receptor in schizophrenia, largely because of the abnormally low levels of glutamate receptors found in the postmortem brains of those diagnosed with schizophrenia, and the discovery that glutamate-blocking drugs such as phencyclidine and ketamine can mimic the symptoms and cognitive problems associated with the condition. Reduced glutamate function is linked to poor performance on tests requiring frontal lobe and hippocampal function, and glutamate can affect dopamine function, both of which have been implicated in schizophrenia, have suggested an important mediating (and possibly causal) role of glutamate pathways in the condition. But positive symptoms fail to respond to glutamatergic medication.

Diagnosis

Main article: Diagnosis of schizophrenia

Schizophrenia is diagnosed based on criteria in either the American Psychiatric Association's fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM 5), or the World Health Organization's International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-10). These criteria use the self-reported experiences of the person and reported abnormalities in behavior, followed by a clinical assessment by a mental health professional. Symptoms associated with schizophrenia occur along a continuum in the population and must reach a certain severity before a diagnosis is made. As of 2013 there is no objective test.

Criteria

In 2013, the American Psychiatric Association released the fifth edition of the DSM (DSM-5). To be diagnosed with schizophrenia, two diagnostic criteria have to be met over much of the time of a period of at least one month, with a significant impact on social or occupational functioning for at least six months. The person had to be suffering from delusions, hallucinations or disorganized speech. A second symptom could be negative symptoms or severely disorganized or catatonic behaviour. The definition of schizophrenia remained essentially the same as that specified by the 2000 version of DSM (DSM-IV-TR), but DSM-5 makes a number of changes.

- Subtype classifications – such as catatonic and paranoid schizophrenia – are removed. These were retained in previous revisions largely for reasons of tradition, but had subsequently proved to be of little worth.

- Catatonia is no longer so strongly associated with schizophrenia.

- In describing a person's schizophrenia, it is recommended that a better distinction be made between the current state of the condition and its historical progress, to achieve a clearer overall characterization.

- Special treatment of Schneider's first-rank symptoms is no longer recommended.

- Schizoaffective disorder is better defined to demarcate it more cleanly from schizophrenia.

- An assessment covering eight domains of psychopathology – such as whether hallucination or mania is experienced – is recommended to help clinical decision-making.

The ICD-10 criteria are typically used in European countries, while the DSM criteria are used in the United States and to varying degrees around the world, and are prevailing in research studies. The ICD-10 criteria put more emphasis on Schneiderian first-rank symptoms. In practice, agreement between the two systems is high.

If signs of disturbance are present for more than a month but less than six months, the diagnosis of schizophreniform disorder is applied. Psychotic symptoms lasting less than a month may be diagnosed as brief psychotic disorder, and various conditions may be classed as psychotic disorder not otherwise specified, while schizoaffective disorder is diagnosed if symptoms of mood disorder are substantially present alongside psychotic symptoms. If the psychotic symptoms are the direct physiological result of a general medical condition or a substance, then the diagnosis is one of a psychosis secondary to that condition. Schizophrenia is not diagnosed if symptoms of pervasive developmental disorder are present unless prominent delusions or hallucinations are also present.

Subtypes

The DSM-5 work group proposed dropping the five sub-classifications of schizophrenia included in DSM-IV-TR:

- Paranoid type: Delusions or auditory hallucinations are present, but thought disorder, disorganized behavior, or affective flattening are not. Delusions are persecutory and/or grandiose, but in addition to these, other themes such as jealousy, religiosity, or somatization may also be present. (DSM code 295.3/ICD code F20.0)

- Disorganized type: Named hebephrenic schizophrenia in the ICD. Where thought disorder and flat affect are present together. (DSM code 295.1/ICD code F20.1)

- Catatonic type: The subject may be almost immobile or exhibit agitated, purposeless movement. Symptoms can include catatonic stupor and waxy flexibility. (DSM code 295.2/ICD code F20.2)

- Undifferentiated type: Psychotic symptoms are present but the criteria for paranoid, disorganized, or catatonic types have not been met. (DSM code 295.9/ICD code F20.3)

- Residual type: Where positive symptoms are present at a low intensity only. (DSM code 295.6/ICD code F20.5)

The ICD-10 defines two additional subtypes:

- Post-schizophrenic depression: A depressive episode arising in the aftermath of a schizophrenic illness where some low-level schizophrenic symptoms may still be present. (ICD code F20.4)

- Simple schizophrenia: Insidious and progressive development of prominent negative symptoms with no history of psychotic episodes. (ICD code F20.6)

Differential

See also: Dual diagnosis and Comparison of bipolar disorder and schizophreniaPsychotic symptoms may be present in several other mental disorders, including bipolar disorder, borderline personality disorder, drug intoxication and drug-induced psychosis. Delusions ("non-bizarre") are also present in delusional disorder, and social withdrawal in social anxiety disorder, avoidant personality disorder and schizotypal personality disorder. Schizotypal personality disorder has symptoms that are similar but less severe than those of schizophrenia. Schizophrenia occurs along with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) considerably more often than could be explained by chance, although it can be difficult to distinguish obsessions that occur in OCD from the delusions of schizophrenia. A small number of people withdrawing from benzodiazepines experience a severe withdrawal syndrome which may last a long time. It can resemble schizophrenia and be misdiagnosed as such.

A more general medical and neurological examination may be needed to rule out medical illnesses which may rarely produce psychotic schizophrenia-like symptoms, such as metabolic disturbance, systemic infection, syphilis, HIV infection, epilepsy, and brain lesions. Stroke, multiple sclerosis, hyperthyroidism, hypothyroidism and dementias such as Alzheimer's disease, Huntington's disease, frontotemporal dementia and Lewy Body dementia may also be associated with schizophrenia-like psychotic symptoms. It may be necessary to rule out a delirium, which can be distinguished by visual hallucinations, acute onset and fluctuating level of consciousness, and indicates an underlying medical illness. Investigations are not generally repeated for relapse unless there is a specific medical indication or possible adverse effects from antipsychotic medication. In children hallucinations must be separated from normal childhood fantasies.

Prevention

Prevention of schizophrenia is difficult as there are no reliable markers for the later development of the disease. There is tentative evidence for the effectiveness of early interventions to prevent schizophrenia. While there is some evidence that early intervention in those with a psychotic episode may improve short-term outcomes, there is little benefit from these measures after five years. Attempting to prevent schizophrenia in the prodrome phase is of uncertain benefit and therefore as of 2009 is not recommended. Cognitive behavioral therapy may reduce the risk of psychosis in those at high risk after a year and is recommended by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in this group. Another preventative measure is to avoid drugs that have been associated with development of the disorder, including cannabis, cocaine, and amphetamines.

Management

Main article: Management of schizophreniaThe primary treatment of schizophrenia is antipsychotic medications, often in combination with psychological and social supports. Hospitalization may occur for severe episodes either voluntarily or (if mental health legislation allows it) involuntarily. Long-term hospitalization is uncommon since deinstitutionalization beginning in the 1950s, although it still occurs. Community support services including drop-in centers, visits by members of a community mental health team, supported employment and support groups are common. Some evidence indicates that regular exercise has a positive effect on the physical and mental health of those with schizophrenia.

Medication

The first-line psychiatric treatment for schizophrenia is antipsychotic medication, which can reduce the positive symptoms of psychosis in about 7 to 14 days. Antipsychotics, however, fail to significantly ameliorate the negative symptoms and cognitive dysfunction. In those on antipsychotics, continued use decreases the risk of relapse. There is little evidence regarding consistent benefits from their use beyond two or three years.

The choice of which antipsychotic to use is based on benefits, risks, and costs. It is debatable whether, as a class, typical or atypical antipsychotics are better, though there is evidence of amisulpride, olanzapine, risperidone and clozapine being the most effective medications. Typical antipsychotics have equal drop-out and symptom relapse rates to atypicals when used at low to moderate dosages. There is a good response in 40–50%, a partial response in 30–40%, and treatment resistance (failure of symptoms to respond satisfactorily after six weeks to two or three different antipsychotics) in 20% of people. Clozapine is an effective treatment for those who respond poorly to other drugs ("treatment-resistant" or "refractory" schizophrenia), but it has the potentially serious side effect of agranulocytosis (lowered white blood cell count) in less than 4% of people.

Most people on antipsychotics get side effects. People on typical antipsychotics tend to have a higher rate of extrapyramidal side effects while some atypicals are associated with considerable weight gain, diabetes and risk of metabolic syndrome; this is most pronounced with olanzapine, while risperidone and quetiapine are also associated with weight gain. Risperidone has a similar rate of extrapyramidal symptoms to haloperidol.

It remains unclear whether the newer antipsychotics reduce the chances of developing neuroleptic malignant syndrome and/or Tardive dyskinesia, a rare but serious neurological disorder.

For people who are unwilling or unable to take medication regularly, long-acting depot preparations of antipsychotics may be used to achieve control. They reduce the risk of relapse to a greater degree than oral medications. When used in combination with psychosocial interventions they may improve long-term adherence to treatment. The American Psychiatric Association suggests considering stopping antipsychotics in some people if there are no symptoms for more than a year.

Psychosocial

A number of psychosocial interventions may be useful in the treatment of schizophrenia including: family therapy, assertive community treatment, supported employment, cognitive remediation, skills training, token economic interventions, and psychosocial interventions for substance use and weight management. Family therapy or education, which addresses the whole family system of an individual, may reduce relapses and hospitalizations. Evidence for the effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) in either reducing symptoms or preventing relapse is minimal. Art or drama therapy have not been well-researched.

Prognosis

Main article: Prognosis of schizophreniaSchizophrenia has great human and economic costs. It results in a decreased life expectancy by 10–25 years. This is primarily because of its association with obesity, poor diet, sedentary lifestyles, and smoking, with an increased rate of suicide playing a lesser role. Antipsychotic medications may also increase the risk. These differences in life expectancy increased between the 1970s and 1990s.

Schizophrenia is a major cause of disability, with active psychosis ranked as the third-most-disabling condition after quadriplegia and dementia and ahead of paraplegia and blindness. Approximately three-fourths of people with schizophrenia have ongoing disability with relapses and 16.7 million people globally are deemed to have moderate or severe disability from the condition. Some people do recover completely and others function well in society. Most people with schizophrenia live independently with community support. In people with a first episode of psychosis a good long-term outcome occurs in 42%, an intermediate outcome in 35% and a poor outcome in 27%. Outcomes for schizophrenia appear better in the developing than the developed world. These conclusions, however, have been questioned.

There is a higher than average suicide rate associated with schizophrenia. This has been cited at 10%, but a more recent analysis revises the estimate to 4.9%, most often occurring in the period following onset or first hospital admission. Several times more (20 to 40%) attempt suicide at least once. There are a variety of risk factors, including male gender, depression, and a high intelligence quotient.

Schizophrenia and smoking have shown a strong association in studies world-wide. Use of cigarettes is especially high in individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia, with estimates ranging from 80 to 90% being regular smokers, as compared to 20% of the general population. Those who smoke tend to smoke heavily, and additionally smoke cigarettes with high nicotine content. Some evidence suggests that paranoid schizophrenia may have a better prospect than other types of schizophrenia for independent living and occupational functioning.

Epidemiology

Schizophrenia affects around 0.3–0.7% of people at some point in their life, or 24 million people worldwide as of 2011. It occurs 1.4 times more frequently in males than females and typically appears earlier in men—the peak ages of onset are 25 years for males and 27 years for females. Onset in childhood is much rarer, as is onset in middle- or old age. Despite the received wisdom that schizophrenia occurs at similar rates worldwide, its frequency varies across the world, within countries, and at the local and neighborhood level. It causes approximately 1% of worldwide disability adjusted life years and resulted in 20,000 deaths in 2010. The rate of schizophrenia varies up to threefold depending on how it is defined.

In 2000, the World Health Organization found the prevalence and incidence of schizophrenia to be roughly similar around the world, with age-standardized prevalence per 100,000 ranging from 343 in Africa to 544 in Japan and Oceania for men and from 378 in Africa to 527 in Southeastern Europe for women.

History

Main article: History of schizophreniaIn the early 20th century, the psychiatrist Kurt Schneider listed the forms of psychotic symptoms that he thought distinguished schizophrenia from other psychotic disorders. These are called first-rank symptoms or Schneider's first-rank symptoms. They include delusions of being controlled by an external force; the belief that thoughts are being inserted into or withdrawn from one's conscious mind; the belief that one's thoughts are being broadcast to other people; and hearing hallucinatory voices that comment on one's thoughts or actions or that have a conversation with other hallucinated voices. Although they have significantly contributed to the current diagnostic criteria, the specificity of first-rank symptoms has been questioned. A review of the diagnostic studies conducted between 1970 and 2005 found that they allow neither a reconfirmation nor a rejection of Schneider's claims, and suggested that first-rank symptoms should be de-emphasized in future revisions of diagnostic systems.

The history of schizophrenia is complex and does not lend itself easily to a linear narrative. Accounts of a schizophrenia-like syndrome are thought to be rare in historical records before the 19th century, although reports of irrational, unintelligible, or uncontrolled behavior were common. A detailed case report in 1797 concerning James Tilly Matthews, and accounts by Phillipe Pinel published in 1809, are often regarded as the earliest cases of the illness in the medical and psychiatric literature. The Latinized term dementia praecox was first used by German alienist Heinrich Schule in 1886 and then in 1891 by Arnold Pick in a case report of a psychotic disorder (hebephrenia). In 1893 Emil Kraepelin borrowed the term from Schule and Pick and in 1899 introduced a broad new distinction in the classification of mental disorders between dementia praecox and mood disorder (termed manic depression and including both unipolar and bipolar depression). Kraepelin believed that dementia praecox was probably caused by a long-term, smouldering systemic or "whole body" disease process that affected many organs and peripheral nerves in the body but which affected the brain after puberty in a final decisive cascade. His use of the term "praecox" distinguished it from other forms of dementia such as Alzheimer's disease which typically occur later in life. It is sometimes argued that the use of the term démence précoce in 1852 by the French physician Bénédict Morel constitutes the medical discovery of schizophrenia. However this account ignores the fact that there is little to connect Morel's descriptive use of the term and the independent development of the dementia praecox disease concept at the end of the nineteenth-century.

The word schizophrenia—which translates roughly as "splitting of the mind" and comes from the Greek roots schizein (σχίζειν, "to split") and phrēn, phren- (φρήν, φρεν-, "mind")—was coined by Eugen Bleuler in 1908 and was intended to describe the separation of function between personality, thinking, memory, and perception. American and British interpretations of Beuler led to the claim that he described its main symptoms as 4 A's: flattened Affect, Autism, impaired Association of ideas and Ambivalence. Bleuler realized that the illness was not a dementia, as some of his patients improved rather than deteriorated, and thus proposed the term schizophrenia instead. Treatment was revolutionized in the mid-1950s with the development and introduction of chlorpromazine.

In the early 1970s, the diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia were the subject of a number of controversies which eventually led to the operational criteria used today. It became clear after the 1971 US-UK Diagnostic Study that schizophrenia was diagnosed to a far greater extent in America than in Europe. This was partly due to looser diagnostic criteria in the US, which used the DSM-II manual, contrasting with Europe and its ICD-9. David Rosenhan's 1972 study, published in the journal Science under the title "On being sane in insane places", concluded that the diagnosis of schizophrenia in the US was often subjective and unreliable. These were some of the factors leading to the revision not only of the diagnosis of schizophrenia, but the revision of the whole DSM manual, resulting in the publication of the DSM-III in 1980. The term schizophrenia is commonly misunderstood to mean that affected persons have a "split personality". Although some people diagnosed with schizophrenia may hear voices and may experience the voices as distinct personalities, schizophrenia does not involve a person changing among distinct multiple personalities. The confusion arises in part due to the literal interpretation of Bleuler's term schizophrenia (Bleuler originally associated Schizophrenia with dissociation and included split personality in his category of Schizophrenia). Dissociative identity disorder (having a "split personality") was also often misdiagnosed as Schizophrenia based on the loose criteria in the DSM-II. The first known misuse of the term to mean "split personality" was in an article by the poet T. S. Eliot in 1933. Other scholars have traced earlier roots.

Society and culture

See also: List of people with schizophrenia and Religion and schizophrenia

In 2002 the term for schizophrenia in Japan was changed from Seishin-Bunretsu-Byō 精神分裂病 (mind-split-disease) to Tōgō-shitchō-shō 統合失調症 (integration disorder) to reduce stigma. The new name was inspired by the biopsychosocial model; it increased the percentage of patients who were informed of the diagnosis from 37 to 70% over three years. A similar change was made in South Korea in 2012.

In the United States, the cost of schizophrenia—including direct costs (outpatient, inpatient, drugs, and long-term care) and non-health care costs (law enforcement, reduced workplace productivity, and unemployment)—was estimated to be $62.7 billion in 2002. The book and film A Beautiful Mind chronicles the life of John Forbes Nash, a Nobel Prize-winning mathematician who was diagnosed with schizophrenia.

Violence

Individuals with severe mental illness including schizophrenia are at a significantly greater risk of being victims of both violent and non-violent crime. Schizophrenia has been associated with a higher rate of violent acts, although this is primarily due to higher rates of drug use. Rates of homicide linked to psychosis are similar to those linked to substance misuse, and parallel the overall rate in a region. What role schizophrenia has on violence independent of drug misuse is controversial, but certain aspects of individual histories or mental states may be factors.

Media coverage relating to violent acts by individuals with schizophrenia reinforces public perception of an association between schizophrenia and violence. In a large, representative sample from a 1999 study, 12.8% of Americans believed that individuals with schizophrenia were "very likely" to do something violent against others, and 48.1% said that they were "somewhat likely" to. Over 74% said that people with schizophrenia were either "not very able" or "not able at all" to make decisions concerning their treatment, and 70.2% said the same of money management decisions. The perception of individuals with psychosis as violent has more than doubled in prevalence since the 1950s, according to one meta-analysis.

Research directions

See also: Animal models of schizophreniaResearch has found a tentative benefit in using minocycline to treat schizophrenia. Nidotherapy or efforts to change the environment of people with schizophrenia to improve their ability to function, is also being studied; however, there is not enough evidence yet to make conclusions about its effectiveness.

References

- ^ Picchioni MM, Murray RM (July 2007). "Schizophrenia". BMJ. 335 (7610): 91–5. doi:10.1136/bmj.39227.616447.BE. PMC 1914490. PMID 17626963.

- Baucum, Don (2006). Psychology (2nd ed.). Hauppauge, N.Y.: Barron's. p. 182. ISBN 9780764134210.

- ^ Becker T, Kilian R (2006). "Psychiatric services for people with severe mental illness across western Europe: what can be generalized from current knowledge about differences in provision, costs and outcomes of mental health care?". Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica Supplement. 113 (429): 9–16. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2005.00711.x. PMID 16445476.

- ^ van Os J, Kapur S (August 2009). "Schizophrenia" (PDF). Lancet. 374 (9690): 635–45. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60995-8. PMID 19700006.

- Buckley PF, Miller BJ, Lehrer DS, Castle DJ (March 2009). "Psychiatric comorbidities and schizophrenia". Schizophr Bull. 35 (2): 383–402. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbn135. PMC 2659306. PMID 19011234.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Laursen TM, Munk-Olsen T, Vestergaard, M (March 2012). "Life expectancy and cardiovascular mortality in persons with schizophrenia". Current opinion in psychiatry. 25 (2): 83–8. doi:10.1097/YCO.0b013e32835035ca. PMID 22249081.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hor K, Taylor M (November 2010). "Suicide and schizophrenia: a systematic review of rates and risk factors". Journal of psychopharmacology (Oxford, England). 24 (4 Suppl): 81–90. doi:10.1177/1359786810385490. PMID 20923923.

- ^ Carson VB (2000). Mental health nursing: the nurse-patient journey W.B. Saunders. ISBN 978-0-7216-8053-8. p. 638.

- Hirsch SR; Weinberger DR (2003). Schizophrenia. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-632-06388-8.

- Brunet-Gouet E, Decety J (December 2006). "Social brain dysfunctions in schizophrenia: a review of neuroimaging studies". Psychiatry Res. 148 (2–3): 75–92. doi:10.1016/j.pscychresns.2006.05.001. PMID 17088049.

- Hirsch SR; WeinbergerDR (2003). Schizophrenia. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 481. ISBN 978-0-632-06388-8.

- Ungvari GS, Caroff SN, Gerevich J (March 2010). "The catatonia conundrum: evidence of psychomotor phenomena as a symptom dimension in psychotic disorders". Schizophr Bull. 36 (2): 231–8. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbp105. PMC 2833122. PMID 19776208.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Baier M (August 2010). "Insight in schizophrenia: a review". Current psychiatry reports. 12 (4): 356–61. doi:10.1007/s11920-010-0125-7. PMID 20526897.

- Pijnenborg GH, van Donkersgoed RJ, David AS, Aleman A (March 2013). "Changes in insight during treatment for psychotic disorders: a meta-analysis". Schizophrenia research. 144 (1–3): 109–17. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2012.11.018. PMID 23305612.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Kohler CG, Walker JB, Martin EA, Healey KM, Moberg PJ (September 2010). "Facial emotion perception in schizophrenia: a meta-analytic review". Schizophr Bull. 36 (5): 1009–19. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbn192. PMC 2930336. PMID 19329561.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Sims A (2002). Symptoms in the mind: an introduction to descriptive psychopathology. Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders. ISBN 0-7020-2627-1.

- Kneisl C. and Trigoboff E. (2009). Contemporary Psychiatric- Mental Health Nursing. 2nd edition. London: Pearson Prentice Ltd. p. 371

- ^ American Psychiatric Association. Task Force on DSM-IV. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-IV-TR. American Psychiatric Pub. ISBN 978-0-89042-025-6. p. 299

- Velligan DI and Alphs LD (1 March 2008). "Negative Symptoms in Schizophrenia: The Importance of Identification and Treatment". Psychiatric Times. 25 (3).

- ^ Smith T, Weston C, Lieberman J (August 2010). "Schizophrenia (maintenance treatment)". Am Fam Physician. 82 (4): 338–9. PMID 20704164.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Addington J, Cadenhead KS, Cannon TD; et al. (2007). "North American prodrome longitudinal study: a collaborative multisite approach to prodromal schizophrenia research". Schizophrenia Bulletin. 33 (3): 665–72. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbl075. PMC 2526151. PMID 17255119.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Cullen KR, Kumra S, Regan J; et al. (2008). "Atypical Antipsychotics for Treatment of Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorders". Psychiatric Times. 25 (3).

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Amminger GP, Leicester S, Yung AR; et al. (2006). "Early onset of symptoms predicts conversion to non-affective psychosis in ultra-high risk individuals". Schizophrenia Research. 84 (1): 67–76. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2006.02.018. PMID 16677803.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Parnas J, Jorgensen A (1989). "Pre-morbid psychopathology in schizophrenia spectrum". British Journal of Psychiatry. 115: 623–7. PMID 2611591.

- ^ Coyle, Joseph (2006). "Chapter 54: The Neurochemistry of Schizophrenia". In Siegal, George J; et al. (eds.). Basic Neurochemistry: Molecular, Cellular and Medical Aspects (7th ed.). Burlington, MA: Elsevier Academic Press. pp. 876–78. ISBN 0-12-088397-X.

{{cite book}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|editor=(help) - Drake RJ, Lewis SW (March 2005). "Early detection of schizophrenia". Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 18 (2): 147–50. doi:10.1097/00001504-200503000-00007. PMID 16639167.

- O'Donovan MC, Williams NM, Owen MJ (October 2003). "Recent advances in the genetics of schizophrenia". Hum. Mol. Genet. 12 Spec No 2: R125–33. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddg302. PMID 12952866.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Herson M (2011). "Etiological considerations". Adult psychopathology and diagnosis. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9781118138847.

- McLaren JA, Silins E, Hutchinson D, Mattick RP, Hall W (January 2010). "Assessing evidence for a causal link between cannabis and psychosis: a review of cohort studies". Int. J. Drug Policy. 21 (1): 10–9. doi:10.1016/j.drugpo.2009.09.001. PMID 19783132.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - O'Donovan MC, Craddock NJ, Owen MJ (July 2009). "Genetics of psychosis; insights from views across the genome". Hum. Genet. 126 (1): 3–12. doi:10.1007/s00439-009-0703-0. PMID 19521722.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Craddock N, Owen MJ (2010). "The Kraepelinian dichotomy - going, going... But still not gone". The British Journal of Psychiatry. 196: 92–95. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.109.073429. PMC 2815936. PMID 20118450.

- Moore S, Kelleher E, Corvin A. (2011). "The shock of the new: progress in schizophrenia genomics". Current Genomics. 12 (7): 516–24. doi:10.2174/138920211797904089. PMC 3219846. PMID 22547958.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Crow TJ (July 2008). "The 'big bang' theory of the origin of psychosis and the faculty of language". Schizophrenia Research. 102 (1–3): 31–52. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2008.03.010. PMID 18502103.

- Mueser KT, Jeste DV (2008). Clinical Handbook of Schizophrenia. New York: Guilford Press. pp. 22–23. ISBN 1-59385-652-0.

- "THE ABANDONED ILLNESS" (PDF). Schizophrenia Commission. November 2012. p. 10. Retrieved 19 April 2014.

- Van Os J (2004). "Does the urban environment cause psychosis?". British Journal of Psychiatry. 184 (4): 287–288. doi:10.1192/bjp.184.4.287. PMID 15056569.

- Selten JP, Cantor-Graae E, Kahn RS (March 2007). "Migration and schizophrenia". Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 20 (2): 111–115. doi:10.1097/YCO.0b013e328017f68e. PMID 17278906.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Gregg L, Barrowclough C, Haddock G (2007). "Reasons for increased substance use in psychosis". Clin Psychol Rev. 27 (4): 494–510. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2006.09.004. PMID 17240501.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Larson, Michael (30 March 2006). "Alcohol-Related Psychosis". eMedicine. WebMD. Retrieved 27 September 2006.

- Sagud M, Mihaljević-Peles A, Mück-Seler D; et al. (September 2009). "Smoking and schizophrenia" (PDF). Psychiatr Danub. 21 (3): 371–5. PMID 19794359.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Alcohol-Related Psychosis at eMedicine

- Large M, Sharma S, Compton MT, Slade T, Nielssen O (June 2011). "Cannabis use and earlier onset of psychosis: a systematic meta-analysis". Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 68 (6): 555–61. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.5. PMID 21300939.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Chadwick B, Miller ML, Hurd YL (2013). "Cannabis Use during Adolescent Development: Susceptibility to Psychiatric Illness". Front Psychiatry (Review). 4: 129. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2013.00129. PMC 3796318. PMID 24133461.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Niesink RJ, van Laar MW (2013). "Does cannabidiol protect against adverse psychological effects of THC?". Frontiers in Psychiatry (Review). 4: 130. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2013.00130. PMC 3797438. PMID 24137134.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Parakh P, Basu D (August 2013). "Cannabis and psychosis: have we found the missing links?". Asian Journal of Psychiatry (Review). 6 (4): 281–7. doi:10.1016/j.ajp.2013.03.012. PMID 23810133.

Cannabis acts as a component cause of psychosis, that is, it increases the risk of psychosis in people with certain genetic or environmental vulnerabilities, though by itself, it is neither a sufficient nor a necessary cause of psychosis.

- Leweke FM, Koethe D (June 2008). "Cannabis and psychiatric disorders: it is not only addiction". Addict Biol. 13 (2): 264–75. doi:10.1111/j.1369-1600.2008.00106.x. PMID 18482435.

- Yolken R. (June 2004). "Viruses and schizophrenia: a focus on herpes simplex virus". Herpes. 11 (Suppl 2): 83A – 88A. PMID 15319094.

- Broome MR, Woolley JB, Tabraham P; et al. (November 2005). "What causes the onset of psychosis?". Schizophr. Res. 79 (1): 23–34. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2005.02.007. PMID 16198238.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Bentall RP, Fernyhough C, Morrison AP, Lewis S, Corcoran R (2007). "Prospects for a cognitive-developmental account of psychotic experiences". Br J Clin Psychol. 46 (Pt 2): 155–73. doi:10.1348/014466506X123011. PMID 17524210.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Kurtz MM (2005). "Neurocognitive impairment across the lifespan in schizophrenia: an update". Schizophrenia Research. 74 (1): 15–26. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2004.07.005. PMID 15694750.

- Cohen AS, Docherty NM (2004). "Affective reactivity of speech and emotional experience in patients with schizophrenia". Schizophrenia Research. 69 (1): 7–14. doi:10.1016/S0920-9964(03)00069-0. PMID 15145465.

- Horan WP, Blanchard JJ (2003). "Emotional responses to psychosocial stress in schizophrenia: the role of individual differences in affective traits and coping". Schizophrenia Research. 60 (2–3): 271–83. doi:10.1016/S0920-9964(02)00227-X. PMID 12591589.

- Smith B, Fowler DG, Freeman D; et al. (September 2006). "Emotion and psychosis: links between depression, self-esteem, negative schematic beliefs and delusions and hallucinations". Schizophr. Res. 86 (1–3): 181–8. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2006.06.018. PMID 16857346.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Beck, AT (2004). "A Cognitive Model of Schizophrenia". Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy. 18 (3): 281–88. doi:10.1891/jcop.18.3.281.65649.

- Bell V, Halligan PW, Ellis HD (2006). "Explaining delusions: a cognitive perspective". Trends in Cognitive Science. 10 (5): 219–26. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2006.03.004. PMID 16600666.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Freeman D, Garety PA, Kuipers E, Fowler D, Bebbington PE, Dunn G (January 2007). "Acting on persecutory delusions: the importance of safety seeking". Behav Res Ther. 45 (1): 89–99. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2006.01.014. PMID 16530161.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Kuipers E, Garety P, Fowler D, Freeman D, Dunn G, Bebbington P (October 2006). "Cognitive, emotional, and social processes in psychosis: refining cognitive behavioral therapy for persistent positive symptoms". Schizophr Bull. 32 Suppl 1: S24–31. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbl014. PMC 2632539. PMID 16885206.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Kircher, Tilo and Renate Thienel (2006). "Functional brain imaging of symptoms and cognition in schizophrenia". The Boundaries of Consciousness. Amsterdam: Elsevier. p. 302. ISBN 0-444-52876-8.

- Green MF (2006). "Cognitive impairment and functional outcome in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder". Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 67 (Suppl 9): 3–8. doi:10.4088/jcp.1006e12. PMID 16965182.

- Insel TR (November 2010). "Rethinking schizophrenia". Nature. 468 (7321): 187–93. doi:10.1038/nature09552. PMID 21068826.

- "Antipsychotics for schizophrenia associated with subtle loss in brain volume". ScienceDaily. 8 February 2011. Retrieved 3 July 2014.

- Laruelle M, Abi-Dargham A, van Dyck CH; et al. (August 1996). "Single photon emission computerized tomography imaging of amphetamine-induced dopamine release in drug-free schizophrenic subjects". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93 (17): 9235–40. doi:10.1073/pnas.93.17.9235. PMC 38625. PMID 8799184.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Jones HM, Pilowsky LS (2002). "Dopamine and antipsychotic drug action revisited". British Journal of Psychiatry. 181: 271–275. doi:10.1192/bjp.181.4.271. PMID 12356650.

- Konradi C, Heckers S (2003). "Molecular aspects of glutamate dysregulation: implications for schizophrenia and its treatment". Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 97 (2): 153–79. doi:10.1016/S0163-7258(02)00328-5. PMID 12559388.

- Lahti AC, Weiler MA, Tamara Michaelidis BA, Parwani A, Tamminga CA (2001). "Effects of ketamine in normal and schizophrenic volunteers". Neuropsychopharmacology. 25 (4): 455–67. doi:10.1016/S0893-133X(01)00243-3. PMID 11557159.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Coyle JT, Tsai G, Goff D (2003). "Converging evidence of NMDA receptor hypofunction in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1003: 318–27. doi:10.1196/annals.1300.020. PMID 14684455.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Tuominen HJ, Tiihonen J, Wahlbeck K (2005). "Glutamatergic drugs for schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Schizophrenia Research. 72 (2–3): 225–34. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2004.05.005. PMID 15560967.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.). Arlington: American Psychiatric Publishing. pp. 101–05. ISBN 978-0890425558.

- ^ American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.). Arlington: American Psychiatric Publishing. ISBN 978-0890425558.

- ^ Tandon R, Gaebel W, Barch DM; et al. (October 2013). "Definition and description of schizophrenia in the DSM-5". Schizophr. Res. 150 (1): 3–10. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2013.05.028. PMID 23800613.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - As referenced from PMID 23800613, Heckers S, Tandon R, Bustillo J (March 2010). "Catatonia in the DSM--shall we move or not?". Schizophr Bull (Editorial). 36 (2): 205–7. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbp136. PMC 2833126. PMID 19933711.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Barch DM, Bustillo J, Gaebel W; et al. (October 2013). "Logic and justification for dimensional assessment of symptoms and related clinical phenomena in psychosis: relevance to DSM-5". Schizophr. Res. 150 (1): 15–20. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2013.04.027. PMID 23706415.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Jakobsen KD, Frederiksen JN, Hansen T; et al. (2005). "Reliability of clinical ICD-10 schizophrenia diagnoses". Nordic Journal of Psychiatry. 59 (3): 209–12. doi:10.1080/08039480510027698. PMID 16195122.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - American Psychiatric Association DSM-5 Work Groups (2010) Proposed Revisions – Schizophrenia and Other Psychotic Disorders. Retrieved 17 February 2010.

- ^ "The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders" (PDF). World Health Organization. p. 26.

- Pope HG (1983). "Distinguishing bipolar disorder from schizophrenia in clinical practice: guidelines and case reports". Hospital and Community Psychiatry. 34: 322–28.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - McGlashan TH (February 1987). "Testing DSM-III symptom criteria for schizotypal and borderline personality disorders". Archives of General Psychiatry. 44 (2): 143–8. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1987.01800140045007. PMID 3813809.

- Bottas A (15 April 2009). "Comorbidity: Schizophrenia With Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder". Psychiatric Times. 26 (4).

- Gabbard GO (15 May 2007). Gabbard's Treatments of Psychiatric Disorders, Fourth Edition (Treatments of Psychiatric Disorders). American Psychiatric Publishing. pp. 209–11. ISBN 1-58562-216-8.

- Murray ED, Buttner N, Price BH (2012). "Depression and Psychosis in Neurological Practice". In Bradley WG, Daroff RB, Fenichel GM, Jankovic J (ed.). Bradley's neurology in clinical practice. Vol. 1 (6th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders. pp. 92–111. ISBN 1-4377-0434-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Cannon TD, Cornblatt B, McGorry P (May 2007). "The empirical status of the ultra high-risk (prodromal) research paradigm". Schizophrenia Bulletin. 33 (3): 661–4. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbm031. PMC 2526144. PMID 17470445.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Marshall, M; Rathbone, J (15 June 2011). "Early intervention for psychosis". The Cochrane database of systematic reviews (6): CD004718. PMID 21678345.

- de Koning MB, Bloemen OJ, van Amelsvoort TA; et al. (June 2009). "Early intervention in patients at ultra high risk of psychosis: benefits and risks". Acta Psychiatr Scand. 119 (6): 426–42. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2009.01372.x. PMID 19392813.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Stafford MR, Jackson H, Mayo-Wilson E, Morrison AP, Kendall T (18 January 2013). "Early interventions to prevent psychosis: systematic review and meta-analysis". BMJ (Clinical research ed.). 346: f185. doi:10.1136/bmj.f185. PMC 3548617. PMID 23335473.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Psychosis and schizophrenia in adults: treatment and management" (PDF). NICE. March 2014. p. 7. Retrieved 19 April 2014.

- McGurk SR, Mueser KT, Feldman K, Wolfe R, Pascaris A (March 2007). "Cognitive training for supported employment: 2–3 year outcomes of a randomized controlled trial". American Journal of Psychiatry. 164 (3): 437–41. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.164.3.437. PMID 17329468.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Gorczynski P, Faulkner G (2010). "Exercise therapy for schizophrenia". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (5): CD004412. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004412.pub2. PMID 20464730.

- National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health (25 March 2009). "Schizophrenia: Full national clinical guideline on core interventions in primary and secondary care" (PDF). Retrieved 25 November 2009.

- Tandon R, Keshavan MS, Nasrallah HA (March 2008). "Schizophrenia, "Just the Facts": what we know in 2008 part 1: overview" (PDF). Schizophrenia Research. 100 (1–3): 4–19. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2008.01.022. PMID 18291627.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Leucht S, Tardy M, Komossa K; et al. (June 2012). "Antipsychotic drugs versus placebo for relapse prevention in schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Lancet. 379 (9831): 2063–71. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60239-6. PMID 22560607.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Harrow M, Jobe TH (19 March 2013). "Does long-term treatment of dchizophrenia with antipsychotic medications facilitate recovery?". Schizophrenia bulletin. 39 (5): 962–5. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbt034. PMC 3756791. PMID 23512950.

- Kane JM, Correll CU (2010). "Pharmacologic treatment of schizophrenia". Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 12 (3): 345–57. PMC 3085113. PMID 20954430.

- Hartling L, Abou-Setta AM, Dursun S; et al. (14 August 2012). "Antipsychotics in Adults With Schizophrenia: Comparative Effectiveness of First-generation versus second-generation medications: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Annals of Internal Medicine. 157 (7): 498–511. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-157-7-201210020-00525. PMID 22893011.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Barry SJE, Gaughan TM, Hunter R (2012). "Schizophrenia". BMJ Clinical Evidence. PMID 23870705.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Schultz SH, North SW, Shields CG (June 2007). "Schizophrenia: a review". Am Fam Physician. 75 (12): 1821–9. PMID 17619525.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Taylor DM (2000). "Refractory schizophrenia and atypical antipsychotics". J Psychopharmacol. 14 (4): 409–418. doi:10.1177/026988110001400411.

- Essali A, Al-Haj Haasan N, Li C, Rathbone J (2009). "Clozapine versus typical neuroleptic medication for schizophrenia". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (1): CD000059. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000059.pub2. PMID 19160174.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Ananth J, Parameswaran S, Gunatilake S, Burgoyne K, Sidhom T (April 2004). "Neuroleptic malignant syndrome and atypical antipsychotic drugs". Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 65 (4): 464–70. doi:10.4088/JCP.v65n0403. PMID 15119907.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ McEvoy JP (2006). "Risks versus benefits of different types of long-acting injectable antipsychotics". J Clin Psychiatry. 67 Suppl 5: 15–8. PMID 16822092.

- ^ Pharoah F, Mari J, Rathbone J, Wong W (2010). "Family intervention for schizophrenia". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 12 (12): CD000088. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000088.pub3. PMID 21154340.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Medalia A, Choi J (2009). "Cognitive remediation in schizophrenia" (PDF). Neuropsychology Rev. 19 (3): 353–364. doi:10.1007/s11065-009-9097-y. PMID 19444614.

- Dixon LB, Dickerson F, Bellack AS; et al. (January 2010). "The 2009 schizophrenia PORT psychosocial treatment recommendations and summary statements". Schizophr Bull. 36 (1): 48–70. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbp115. PMC 2800143. PMID 19955389.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Jauhar S, McKenna PJ, Radua J; et al. (January 2014). "Cognitive-behavioural therapy for the symptoms of schizophrenia: systematic review and meta-analysis with examination of potential bias". The British journal of psychiatry : the journal of mental science (Review). 204 (1): 20–9. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.112.116285. PMID 24385461.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Jones C, Cormac I, Silveira da Mota Neto JI, Campbell C (2004). "Cognitive behaviour therapy for schizophrenia". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (4): CD000524. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000524.pub2. PMID 15495000.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Ruddy R, Milnes D (2005). "Art therapy for schizophrenia or schizophrenia-like illnesses". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (4): CD003728. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003728.pub2. PMID 16235338.

- Ruddy RA, Dent-Brown K (2007). "Drama therapy for schizophrenia or schizophrenia-like illnesses". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (1): CD005378. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005378.pub2. PMID 17253555.

- Saha S, Chant D, McGrath J (October 2007). "A systematic review of mortality in schizophrenia: is the differential mortality gap worsening over time?". Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 64 (10): 1123–31. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.64.10.1123. PMID 17909124.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Ustun TB, Rehm J, Chatterji S, Saxena S, Trotter R, Room R, Bickenbach J, and the WHO/NIH Joint Project CAR Study Group (1999). "Multiple-informant ranking of the disabling effects of different health conditions in 14 countries". The Lancet. 354 (9173): 111–15. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(98)07507-2. PMID 10408486.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - World Health Organization (2008). The global burden of disease : 2004 update ( ed.). Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. p. 35. ISBN 9789241563710.

- Warner R (July 2009). "Recovery from schizophrenia and the recovery model". Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 22 (4): 374–80. doi:10.1097/YCO.0b013e32832c920b. PMID 19417668.

- Menezes NM, Arenovich T, Zipursky RB (October 2006). "A systematic review of longitudinal outcome studies of first-episode psychosis". Psychol Med. 36 (10): 1349–62. doi:10.1017/S0033291706007951. PMID 16756689.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Isaac M, Chand P, Murthy P (August 2007). "Schizophrenia outcome measures in the wider international community". Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 50: s71–7. PMID 18019048.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Cohen A, Patel V, Thara R, Gureje O (March 2008). "Questioning an axiom: better prognosis for schizophrenia in the developing world?". Schizophr Bull. 34 (2): 229–44. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbm105. PMC 2632419. PMID 17905787.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Burns J (August 2009). "Dispelling a myth: developing world poverty, inequality, violence and social fragmentation are not good for outcome in schizophrenia". Afr J Psychiatry (Johannesbg). 12 (3): 200–5. doi:10.4314/ajpsy.v12i3.48494. PMID 19894340.

- Palmer BA, Pankratz VS, Bostwick JM (March 2005). "The lifetime risk of suicide in schizophrenia: a reexamination". Archives of General Psychiatry. 62 (3): 247–53. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.62.3.247. PMID 15753237.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Carlborg A, Winnerbäck K, Jönsson EG, Jokinen J, Nordström P (July 2010). "Suicide in schizophrenia". Expert Rev Neurother. 10 (7): 1153–64. doi:10.1586/ern.10.82. PMID 20586695.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - De Leon J, Diaz FJ (2005). "A meta-analysis of worldwide studies demonstrates an association between schizophrenia and tobacco smoking behaviors". Schizophrenia research. 76 (2–3): 135–57. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2005.02.010. PMID 15949648.

- ^ Keltner NL, Grant JS (2006). "Smoke, Smoke, Smoke That Cigarette". Perspectives in Psychiatric Care. 42 (4): 256–61. doi:10.1111/j.1744-6163.2006.00085.x. PMID 17107571.

- American Psychiatric Association. Task Force on DSM-IV. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-IV-TR. American Psychiatric Pub. ISBN 978-0-89042-025-6. p. 304

- American Psychiatric Association. Task Force on DSM-IV. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-IV-TR. American Psychiatric Pub. ISBN 978-0-89042-025-6. p. 314

- "Schizophrenia". World Health Organization. 2011. Retrieved 27 February 2011.

- Cascio MT, Cella M, Preti A, Meneghelli A, Cocchi A (May 2012). "Gender and duration of untreated psychosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Early intervention in psychiatry (Review). 6 (2): 115–27. doi:10.1111/j.1751-7893.2012.00351.x. PMID 22380467.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Kumra S, Shaw M, Merka P, Nakayama E, Augustin R (2001). "Childhood-onset schizophrenia: research update". Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 46 (10): 923–30. PMID 11816313.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Hassett Anne, et al. (eds) (2005). Psychosis in the Elderly. London: Taylor and Francis. p. 6. ISBN 1-84184-394-6.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help) - Jablensky A, Sartorius N, Ernberg G; et al. (1992). "Schizophrenia: manifestations, incidence and course in different cultures. A World Health Organization ten-country study". Psychological Medicine Monograph Supplement. 20: 1–97. doi:10.1017/S0264180100000904. PMID 1565705.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Kirkbride JB, Fearon P, Morgan C; et al. (March 2006). "Heterogeneity in incidence rates of schizophrenia and other psychotic syndromes: findings from the 3-center AeSOP study". Archives of General Psychiatry. 63 (3): 250–8. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.63.3.250. PMID 16520429.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Kirkbride JB, Fearon P, Morgan C; et al. (2007). "Neighbourhood variation in the incidence of psychotic disorders in Southeast London". Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 42 (6): 438–45. doi:10.1007/s00127-007-0193-0. PMID 17473901.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K; et al. (December 2012). "Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010". Lancet. 380 (9859): 2095–128. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0. PMID 23245604.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Ayuso-Mateos JL. "Global burden of schizophrenia in the year 2000" (PDF). World Health Organization. Retrieved 27 February 2013.

- Schneider, K (1959). Clinical Psychopathology (5 ed.). New York: Grune & Stratton.

- Nordgaard J, Arnfred SM, Handest P, Parnas J (January 2008). "The diagnostic status of first-rank symptoms". Schizophrenia Bulletin. 34 (1): 137–54. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbm044. PMC 2632385. PMID 17562695.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - =Yuhas, Daisy. "Throughout History, Defining Schizophrenia Has Remained a Challenge". Scientific American Mind (March/April 2013). Retrieved 3 March 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - Heinrichs RW (2003). "Historical origins of schizophrenia: two early madmen and their illness". Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences. 39 (4): 349–63. doi:10.1002/jhbs.10152. PMID 14601041.

- Noll, Richard (2011). American madness: the rise and fall of dementia praecox. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-04739-6.

- Noll R (2012). "Whole body madness". Psychiatric Times. 29 (12): 13–14.

- Hansen RA, Atchison B (2000). Conditions in occupational therapy: effect on occupational performance. Hagerstown, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 0-683-30417-8.

- Berrios G.E., Luque R, Villagran J (2003). "Schizophrenia: a conceptual history". International Journal of Psychology and Psychological Therapy. 3 (2): 111–140.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Kuhn R (2004). "Eugen Bleuler's concepts of psychopathology". History of Psychiatry. 15 (3). tr. Cahn CH: 361–6. doi:10.1177/0957154X04044603. PMID 15386868.

- Stotz-Ingenlath G (2000). "Epistemological aspects of Eugen Bleuler's conception of schizophrenia in 1911" (PDF). Medicine, Health Care and Philosophy. 3 (2): 153–9. doi:10.1023/A:1009919309015. PMID 11079343.

- McNally K (2009). "Eugen Bleuler's "Four A's"". History of Psychology. 12 (2): 43–59. doi:10.1037/a0015934. PMID 19831234.

- Turner T (2007). "Unlocking psychosis". British Medical Journal. 334 (suppl): s7. doi:10.1136/bmj.39034.609074.94. PMID 17204765.

- Wing JK (January 1971). "International comparisons in the study of the functional psychoses". British Medical Bulletin. 27 (1): 77–81. PMID 4926366.

- Rosenhan D (1973). "On being sane in insane places". Science. 179 (4070): 250–8. doi:10.1126/science.179.4070.250. PMID 4683124.

- Wilson M (March 1993). "DSM-III and the transformation of American psychiatry: a history". American Journal of Psychiatry. 150 (3): 399–410. PMID 8434655.

- Stotz-Ingenlath G: Epistemological aspects of Eugen Bleuler’s conception of schizophrenia in 1911. Med Health Care Philos 2000; 3:153—159

- ^ Hayes, J. A., & Mitchell, J. C. (1994). Mental health professionals' skepticism about multiple personality disorder. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 25, 410-415

- Putnam, Frank W. (1989). Diagnosis and Treatment of Multiple Personality Disorder. New York: The Guilford Press. pp. 351. ISBN 0-89862-177-1

- Berrios, G. E.; Porter, Roy (1995). A history of clinical psychiatry: the origin and history of psychiatric disorders. London: Athlone Press. ISBN 0-485-24211-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - McNally K (Winter 2007). "Schizophrenia as split personality/Jekyll and Hyde: the origins of the informal usage in the English language". Journal of the history of the behavioral sciences. 43 (1): 69–79. doi:10.1002/jhbs.20209. PMID 17205539.

- Kim Y, Berrios GE (2001). "Impact of the term schizophrenia on the culture of ideograph: the Japanese experience". Schizophr Bull. 27 (2): 181–5. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a006864. PMID 11354585.

- Sato M (2004). "Renaming schizophrenia: a Japanese perspective". World Psychiatry. 5 (1): 53–55. PMC 1472254. PMID 16757998.

- Lee, Yu Sang; Kim, Jae-Jin; Kwon, Jun Soo. "Renaming schizophrenia in South Korea". The Lancet. 382 (9893): 683–684. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61776-6.

- Wu EQ (2005). "The economic burden of schizophrenia in the United States in 2002". J Clin Psychiatry. 66 (9): 1122–9. doi:10.4088/jcp.v66n0906. PMID 16187769.

- Maniglio R (March 2009). "Severe mental illness and criminal victimization: a systematic review". Acta Psychiatr Scand. 119 (3): 180–91. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2008.01300.x. PMID 19016668.

- ^ Fazel S, Gulati G, Linsell L, Geddes JR, Grann M (August 2009). "Schizophrenia and violence: systematic review and meta-analysis". PLoS Med. 6 (8): e1000120. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000120. PMC 2718581. PMID 19668362.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - Large M, Smith G, Nielssen O (July 2009). "The relationship between the rate of homicide by those with schizophrenia and the overall homicide rate: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Schizophr. Res. 112 (1–3): 123–9. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2009.04.004. PMID 19457644.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Bo S, Abu-Akel A, Kongerslev M, Haahr UH, Simonsen E (July 2011). "Risk factors for violence among patients with schizophrenia". Clin Psychol Rev. 31 (5): 711–26. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2011.03.002. PMID 21497585.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Pescosolido BA, Monahan J, Link BG, Stueve A, Kikuzawa S (September 1999). "The public's view of the competence, dangerousness, and need for legal coercion of persons with mental health problems". American Journal of Public Health. 89 (9): 1339–45. doi:10.2105/AJPH.89.9.1339. PMC 1508769. PMID 10474550.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Phelan JC, Link BG, Stueve A, Pescosolido BA (June 2000). "Public Conceptions of Mental Illness in 1950 and 1996: What Is Mental Illness and Is It to be Feared?". Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 41 (2): 188–207. doi:10.2307/2676305.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Dean OM, Data-Franco J, Giorlando F, Berk M (1 May 2012). "Minocycline: therapeutic potential in psychiatry". CNS Drugs. 26 (5): 391–401. doi:10.2165/11632000-000000000-00000. PMID 22486246.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Chamberlain IJ, Sampson S (28 March 2013). Chamberlain, Ian J (ed.). "Nidotherapy for people with schizophrenia". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 3: CD009929. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009929.pub2. PMID 23543583.

External links

| Mental disorders (Classification) | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

Template:Link GA Template:Link FA

Categories: