This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Paskwamostos (talk | contribs) at 20:34, 21 November 2014 (Added info on xZineCorez, the cataloguing standard for zines). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 20:34, 21 November 2014 by Paskwamostos (talk | contribs) (Added info on xZineCorez, the cataloguing standard for zines)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

A zine (/ˈziːn/ ZEEN; an abbreviation of fanzine, or magazine) is most commonly a small circulation self-published work of original or appropriated texts and images usually reproduced via photocopier.

A popular definition includes that circulation must be 1,000 or fewer, although in practice the majority are produced in editions of less than 100, and profit is not the primary intent of publication. They are informed by anarchopunk and DIY ethos.

Zines are written in a variety of formats, from desktop published text to comics to handwritten text (an example being the hardcore punk zine Cometbus). Print remains the most popular zine format, usually photocopied with a small circulation. Topics covered are broad, including fanfiction, politics, art and design, ephemera, personal journals, social theory, riot grrrl and intersectional feminism, single topic obsession, or sexual content far enough outside of the mainstream to be prohibitive of inclusion in more traditional media. The time and materials necessary to create a zine are seldom matched by revenue from sale of zines.

Small circulation zines are often not explicitly copyrighted and there is a strong belief among many zine creators that the material within should be freely distributed. In recent years a number of photocopied zines have risen to prominence or professional status and have found wide bookstore and online distribution. Notable among these are Giant Robot, Dazed & Confused, Bust, Bitch, Cometbus, Doris, Brainscan, and Maximum RocknRoll.

History

Origins and overview

Since the invention of the printing press (if not before), dissidents and marginalized citizens have published their own opinions in leaflet and pamphlet form. Thomas Paine published an exceptionally popular pamphlet titled "Common Sense" that led to insurrectionary revolution. Paine is considered to be a significant early independent publisher and a zinester in his own right, but then, the mass media as we now know it did not exist. A countless number of obscure and famous literary figures would self-publish at some time or another, sometimes as children (often writing out copies by hand), sometimes as adults.

The exact origins of the word "zine" is uncertain, but it was widely in use in the early 1970s, and most likely is a shortened version of the word "Magazine." with at least one zine lamenting the abbreviation. The earliest citation known is from 1946, in Startling Stories.

In the 18th century, Benjamin Franklin also started a literary magazine for psychiatric patients at a Pennsylvania hospital, which was distributed amongst the patients and hospital staff. This could be considered the first zine, since it captures the essence of the philosophy and meaning of zines. The concept of zines clearly had an ancestor in the amateur press movement (a major preoccupation of H. P. Lovecraft), which would in its turn cross-pollinate with the subculture of science fiction fandom in the 1930s.

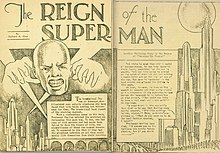

1930s–1960s and science fiction

During and after the Great Depression, editors of "pulp" science fiction magazines became increasingly frustrated with letters detailing the impossibilities of their science fiction stories. Over time they began to publish these overly-scrutinizing letters, complete with their return addresses. This allowed these fans to begin writing to each other, now complete with a mailing list for their own science fiction fanzines.

Fanzines enabled fans to write not only about science fiction but about fandom itself and, in soi-disant perzine (i.e. personal zine), about themselves. As the Damien Broderick novel Transmitters (1984) shows, unlike other, isolated, self-publishers, the more "fannish" (fandom-oriented) fanzine publishers had a shared sensibility and at least as much interest in their relationships between fans as in the literature that inspired it.

A number of leading science fiction and fantasy authors rose through the ranks of fandom, such as Frederik Pohl and Isaac Asimov. George R. R. Martin is also said to have started writing for Fanzines, but has been quoted condemning the practice of fans writing stories set in other authors' worlds.

1970s and punk

Punk zines emerged as part of the punk movement in the late 1970s. These started in the UK and the U.S.A. and by March 1977 had spread to other countries such as Ireland. Cheap photocopying had made it easier than ever for anyone who could make a band flyer to make a zine.

1980s and Factsheet Five

During the 1980s and onwards, Factsheet Five (the name came from a short story by John Brunner), originally published by Mike Gunderloy and now defunct, catalogued and reviewed any zine or small press creation sent to it, along with their mailing addresses. In doing so, it formed a networking point for zine creators and readers (usually the same people). The concept of zine as an art form distinct from fanzine, and of the "zinesters" as member of their own subculture, had emerged. Zines of this era ranged from perzines of all varieties to those that covered an assortment of different and obscure topics that web sites (such as Misplaced Pages) might cover today but for which no large audience existed in the pre-internet era.

1990s and riot grrrl

Although the first feminist zine was printed in 1989 in Minneapolis, Minnesota (Not Your Bitch 1989–1992), it was the 90s that saw the rise of the riot grrrl zine. The early 1990s riot grrrl scene encouraged an explosion of zines of a more raw and explicit nature. Following this, zines enjoyed a brief period of attention from conventional media and a number of zines were collected and published in book form, such as Donna Kossy's Kooks Magazine (1988–1991), published as Kooks (1994, Feral House).

Zines and the Internet

With the rise of the Internet in the late 1990s, zines initially faded from public awareness. It can be argued that the sudden growth of the Internet, and the ability of private web-pages to fulfill much the same role of personal expression as zines, was a strong contributor to their pop culture expiration. Indeed, many zines were transformed into websites, such as Boingboing. However, zines have subsequently been embraced by a new generation, often drawing inspiration from craft, graphic design and artists' books, as well as political and subcultural reasons.

Distribution and circulation

Zines are sold, traded or given as gifts through many different outlets, from zine symposiums and publishing fairs to record stores, book stores, zine stores, at concerts, independent media outlets, zine 'distros', via mail order or through direct correspondence with the author. They are also sold online either via websites, Etsy shops, or social networking profiles.

Zines distributed for free are either traded directly between zinesters, given away at the outlets mentioned or are available to download and print online.

Webzines are found in many places on the Internet.

Publishing

While zines are generally self-published, there are a few independent publishers who specialise in making art zines. One such 'art-zine' publisher (who also publishes books) is Nieves Books in Zurich, founded by Benjamin Sommerhalder. Another is Café Royal Books, UK based and founded by Craig Atkinson in 2005.

Distributors

Zines are most often obtained through mail-order distributors. There are many catalogued and online based mail-order distros for zines. Some of the longer running and most stable operations include Last Gasp in San Francisco, California, Parcell Press in Philadelphia, Microcosm Publishing in Portland, Oregon, Great Worm Express Distribution in Toronto, CornDog Publishing in Ipswich, Café Royal in the UK, Fistful of Books in Scotland, AK Press in Oakland, California, Missing Link Records in Melbourne and Soft Skull Press in Brooklyn, New York. Zine distros often have websites one can place orders on. Because these are small scale DIY projects run by an individual or small group, they often close after only a short time of operation. Those that have been around the longest are often the most dependable.

Bookstores

Some notable examples of bookstores that carry zines:

Australia

United Kingdom

United States

California

Illinois

Indiana

Florida

Maryland

Massachusetts

New York

Ohio

- Guide to Kulchur: Text, Art and News (Cleveland)

- Mac's Backs Paperbacks (Cleveland Heights)

- Cheering and Waving Press(Lancaster, Ohio)

Oklahoma

- Book Beat & Co. (Oklahoma City) defunct

Oregon

Pennsylvania

- Wooden Shoe Books (Philadelphia)

- Little Berlin zine library (Philadelphia)

- The Soapbox zine library (Philadelphia)

- Copacetic Comics Co. (Pittsburgh)

- Big Idea Bookstore website unavailable 11 July 2013 (Pittsburgh)

South Carolina

- Five (Charleston)

Texas

Japan

- Reading Material (Tokyo)

- On Reading (Nagoya)

Indonesia

Zinestores

Sticky Institute (Melbourne, Australia) is a not-for-profit artist-run initiative dedicated solely to the distribution of zines.

Libraries

A number of major public and academic libraries carry zines and other small press publications, often with a specific focus (e.g. women's studies) or those that are relevant to a local region.

Libraries with notable zine collections include Barnard College Library and the University of Iowa Special Collections. The Sallie Bingham Center for Women's History and Culture at Duke University has one of the largest collections of zines on the east coast, housed in the David M. Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscript Library. The Indie Photobook Library, an independent archive in the Washington, DC area, has a large collection of photobook zines from 2010 to the present.

The metadata standard for cataloging zines is xZineCorex, which maps to Dublin Core.

In punk

Zines played an important role in spreading information about different scenes in the punk era (e.g. British fanzines like Mark Perry’s Sniffin Glue and Shane MacGowan’s Bondage).

In the pre-Internet era, zines enabled readers to learn about bands, clubs, and record labels. Zines typically included reviews of shows and records, interviews with bands, letters, and ads for records and labels. Zines were DIY products, "proudly amateur, usually handmade, and always independent" and in the "’90s, zines were the primary way to stay up on punk and hardcore." They acted as the "blogs, comment sections, and social networks of their day."

In the American Midwest, the zine Touch and Go described the Midwest hardcore scene from 1979 to 1983. We Got Power described the LA scene from 1981 to 1984, and it included show reviews and band interviews with groups including D.O.A., the Misfits, Black Flag, Suicidal Tendencies and the Circle Jerks. My Rules was a photo zine that included photos of hardcore shows from across the US. In Effect, which began in 1988, described the New York City scene.

By 1990, Maximum Rocknroll "had become the de facto bible of the scene. A thick, monthly, cheaply printed wad of newsprint crammed with tiny print that came off on the hands", MRR had a "passionate yet dogmatic view" of what hardcore was supposed to be (as an example, MRR declined to review a prominent early emo record by Still Life). HeartattaCk and Profane Existence were "even more religious about its DIY ethos." HeartattaCk was mainly about emo and post-hardcore. Profane Existence was mostly about crust punk.

The Bay Area zine Cometbus "captured an entire dimension of ’90s punk culture that provided necessary roughage compared to the empty calories of mainstream punk’s MTV/Warped Tour narrative." Other 1990 zines included Gearhead, Slug and Lettuce and Riot Grrrl. In Canada, the zine Standard Issue chronicles the Ottawa hardcore scene.

With the arrival of the Internet, some hardcore punk zines became available online. One example is the e-zine chronicling the Australian hardcore scene, RestAssured. Hardcorewebsite.net provides an extensive list of e-zines.

alt.zines

| This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (January 2009) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

The Usenet newsgroup alt.zines was created in 1992 by Jerod Pore and Edward Vielmetti for the discussion of zines and zine-related topics. Since that time, alt.zines has seen more than 26,000 postings.

From the original alt.zines charter: "alt.zines is a place for reviews of zines, announcements of new zines, tips on how to make zines, discussions of the culture of zines, news about zines, specific zines and related stuff."

"Related stuff" has included almost everything under the sun. Throughout the 1990s alt.zines was really the only forum for zinesters to promote, talk, and discuss small publishing issues and tips. And of course argue. It was a place where a zine reader or first time publisher could rub elbows with infamous zinesters. Some of the more infamous alt.zines personalities have included R. Seth Friedman, Rev. Randall Tin-Ear, Doug Holland, Jeff Kay, "Ninjalicious" (AKA Jeff Chapman), Sky Ryan, Tim Brown, Josh Saitz, Dan Halligan, Heath Row, Jeff Koyen, Bob Conrad, Jen Angel, Seth Robson, Karl Wenclas, Asha Anderson, Emerson Dameron, Jerod Pore, Jim Goad, Cullen Carter, Steen Sigmund, Darby Romeo, Jim Hogshire, Debbie Goad, Cali Macvayia, Don Fitch, Jeff Potter, Joel McClemore, Kris Kane, Kelly Dessaint, Marc Parker, Paul T. Olson, Robert W. Howington, Sean Guillory, Ruel Gaviola, Jeff Somers, Tom Hendricks, Chip Rowe, Brent Ritzel and Shaun Richman.

While today there are many other online forums for zinesters and traffic on alt.zines has slowed down dramatically since the zinester flame wars of yesteryear, alt.zines remains one of the most influential places on the web for zine publishers and readers alike. Many long-time alt.zines participants now contribute to ZineWiki.

In fiction

The main character of a Canadian television show produced by the CBC called Our Hero, Kale Stiglic (Cara Pifko) created her own zine.

Damien Broderick's novel Transmitters follows a small group of Australian science fiction fans through their lives over several decades. Pastiches of fanzine writing (from fictitious fanzines) form some of the text of the novel.

Set in the 80s and 90s zine heyday, Walking Man by Tim W. Brown is a comic novel written in the form of a scandalous tell-all biography that portrays the life and times of Brian Walker, publisher of the zine Walking Man, who rises from humble origins to become the most famous zinester in America.

In the novel Hard Love by Ellen Wittlinger, the main character John begins writing a zine called Bananafish after reading other people's zines he found at Tower Records. One of these zines is written by a girl named Marisol who writes a zine called Escape Velocity. After reading her zine, John decides to meet her and their friendship grows from there.

Lunch Money, a children's book by Andrew Clements, has sixth-grader Greg Kenton creating and selling mini comic books, as a way to make money, which leads to one of his classmates making her own publication.

In the Nickelodeon cartoon show Rocket Power, one of main cast characters, Reggie, publishes her own zine about action sports.

Tales of a Punk Rock Nothing is a semi-fictional depiction of the anarcho-punk and riot grrrl scene in early 90s Washington, DC.

In the CBS show How I Met Your Mother, one of the main cast characters, Robin, mentions Riot Grrrl zines in her 90s music video, "P.S. I Love You."

See also

|

|

References

- "February 1972 Issue" (PDF). 'Tapeworm Productions'. Retrieved 2009-01-07.

- "August 1977 Issue of Zine" (PDF). '1901 and all that'. Retrieved 2009-01-07.

- Jesse Sheidlower, Jeff Prucher and Malcolm Farmer eds. "zine". Science Fiction Citations for the OED. Retrieved 2010-10-26.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help) - "Early Irish fanzines". Loserdomzine.com. Retrieved 2007-08-16.

- http://www.jstor.org/discover/10.2307/468079?uid=3739696&uid=2&uid=4&uid=3739256&sid=47698901149927

- "Last Gasp Books". Retrieved 23 February 2011.

- "Welcome to AK Press". Retrieved 23 February 2011.

- "Missing Link Digital". Retrieved 23 February 2011.

- "Soft Skull: Home". Retrieved 23 February 2011.

- "Zine and Amateur Press Collections at the University of Iowa". Retrieved 24 May 2013.

- "Hevelin Collection". Retrieved 24 May 2013.

- "Bingham Center Zine Collections". Retrieved 21 May 2014.

- http://www.indiephotobooklibrary.org/

- Miller, Milo. "xZineCorex: An Introduction" (PDF). Milo Miller. Retrieved 21 November 2014.

Further reading

- Bartel, Julie. From A to Zine: Building a Winning Zine Collection in Your Library. American Library Association, 2004.

- Biel, Joe $100 & a T-shirt: A Documentary About Zines in the Northwest. Microcosm Publishing, 2004, 2005, 2008 (Video)

- Block, Francesca Lia and Hillary Carlip. Zine Scene: The Do It Yourself Guide to Zines. Girl Press, 1998.

- Brent, Bill. Make a Zine!. Black Books, 1997 (1st edn.), ISBN 0-9637401-4-8. Microcosm Publishing, with Biel, Joe, 2008 (2nd edn.), ISBN 978-1-934620-06-9.

- Brown, Tim W. Walking Man, A Novel. Bronx River Press, 2008. ISBN 978-0-9789847-0-0.

- Duncombe, Stephen. Notes from Underground: Zines and the Politics of Alternative Culture. Microcosm Publishing, 1997, 2008. ISBN 1-85984-158-9.

- Kennedy, Pagan. Zine: How I Spent Six Years of My Life in the Underground and Finally...Found Myself...I Think (1995) ISBN 0-312-13628-5.

- Klanten, Robert, Adeline Mollard, Matthias Hübner, and Sonja Commentz, eds. Behind the Zines: Self-Publishing Culture. Berlin: Die Gestalten Verlag, 2011.

- Piepmeier, Alison . Girl Zines: Making Media, Doing Feminism. NYU Press. (2009) ISBN 978-0-8147-6752-8.

- Spencer, Amy. DIY: The Rise of Lo-Fi Culture. Marion Boyars Publishers, Ltd., 2005.

- Watson, Esther and Todd, Mark. "Watcha Mean, What's a Zine?" Graphia, 2006. ISBN 978-0-618-56315-9.

- Vale, V. Zines! Volume 1 (RE/Search, 1996) ISBN 0-9650469-0-7.

- Vale, V. Zines! Volume 2 (RE/Search, 1996) ISBN 0-9650469-2-3.

- Wrekk, Alex. Stolen Sharpie Revolution. Portland: Microcosm Publishing, 2003. ISBN 0-9726967-2-5.

External links

- alti.zines newsgroup

- Zinewiki

- Zine World (review zine) 05/17/2014 Goes to a page saying it's on Hiatus "Indefinitely"

- DIYSearch (search engine and community for the DIY underground with numerous zine listings) 05/17/2014 Looks like this site is down.

| Fan fiction | |

|---|---|

| Genres | |

| Writing styles | |

| Published works | |

| Websites and organizations | |

| Shipping | |

| Related topics | |

| Fandoms | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| By type |

| ||||||

| Demographics | |||||||

| Organizations and events | |||||||

| Publications and activities | |||||||

| Conventions | |||||||

| Topics | |||||||

| Appropriation in the arts | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| By field |

| ||||||||||||||

| General concepts |

| ||||||||||||||

| Related artistic concepts | |||||||||||||||

| Standard blocks and forms | |||||||||||||||

| Epoch-marking works |

| ||||||||||||||

| Theorization | |||||||||||||||

| Related non- artistic concepts | |||||||||||||||

| Intellectual property activism | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Issues | |||||

| Concepts |

| ||||

| Movements | |||||

| Organizations |

| ||||

| People | |||||

| Documentaries | |||||