This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Appleby (talk | contribs) at 18:05, 24 July 2006 (some clean-up. really needs citations.). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 18:05, 24 July 2006 by Appleby (talk | contribs) (some clean-up. really needs citations.)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)

A Korean personal name consists of a family name and a given name, both of which are generally composed of Hanja.

In Korean, as with many other East Asian cultures, the given name follows the family name. When using European languages, some Koreans keep the original order, while others reverse their names to match the Western pattern.

Family names

- See also List of Korean family names

Korean family names were influenced by Chinese family names, and almost all Korean family names consist of one Hanja (hence are one syllable).

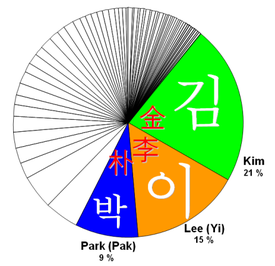

There are only roughly 250 family names (seongssi; 성씨; 姓氏) in use today. Each family name is divided into one or more clans (bon-gwan; 본관; 本貫), identified by the clan's city of origin. The most populous clan is Gimhae (Kimhae) Kim (김해 김; 金海金); that is, the Kim clan based in the city of Gimhae (near Busan).

According to tradition, each clan publishes a comprehensive genealogy (jokbo; 족보; 族譜) every 30 years. (See Nahm 1988, p. 33–34 for more information.)

The table below lists the five most common family names, which together make up over half of the Korean population. Each name is held by more than 2 million people in South Korea alone.

| Hangul | Hanja | Revised | MR | Popular spellings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 김 | 金 | Gim | Kim | Kim |

| 리 (N) 이 (S) |

李 | Ri (N) I (S) |

Ri (N) I (S) |

Lee, Rhee, Yi |

| 박 | 朴 | Bak | Pak | Park, Pak |

| 정 | 鄭 丁 |

Jeong | Chŏng | Chung, Chong, Jung |

| 최 | 崔 | Choe | Ch'oe | Choi |

There are around a dozen two-syllable surnames, which all rank after the 100 most common surnames. Most of them are uncommon Chinese surnames as well (see List of Korean family names for examples, and Chinese compound surname).

Despite the official romanization systems of North and South Korea, personal names are generally romanized according to personal preference.

As with other East Asian cultures, Korean women traditionally keep their family name at marriage, but children take their father's name.

Westernized pronunciations

In English speaking nations, the three most common family names are often written and pronounced as "Kim" (김), "Lee" or "Rhee" (리, 이), and "Park" (박).

The initial sound in "Kim" shares features with both the English 'k' (in initial position, an aspirated voiceless velar stop) and "hard g" (an unaspirated voiced velar stop). When pronounced initially, Kim starts with an unaspirated voiceless velar stop sound; it is voiceless like /k/, but also unaspirated like /g/. As aspiration is a distinctive feature in Korean but voicing isn't, "Gim" is more likely to be understood correctly.

The name-character 李 is pronounced as 리 in North Korea and as 이 in South Korea. In the former case, the initial sound is an alveolar flap, an allophone of the Korean alveolar liquid. There is no distinction between the alveolar liquids /l/ and /r/, which is why "Lee" and "Rhee" are common spellings. In South Korea, the pronunciation of the name is simply the English vowel sound for a "long e", as in see. This pronunciation is often spelled as "Yi" or another similar variation.

In Korean pronunciation, the name Westerners usually render as "park" actually has no 'r' sound at all. Its initial sound is an unaspirated voiceless bilabial stop, like a cross between English 'p' and 'b', and the the vowel is the IPA sound , typically pronounced as the 'a' in father. The "ㅏ" sound is almost identical to the short 'a' vowel in northern British English pronunciation.

Given names

Korean given names are usually composed of two characters or syllables.

Traditionally, given names for males are partly determined by generation names (dollimja, 돌림자), a custom originating in China. One of the two characters in a given name is unique to the individual and the other is shared by all people in a family of the generation. Therefore, it is common for cousins to have the same character (dollimja) in their given names in a fixed position.

In March 1991, the Supreme Court of South Korea published the Table of Hanja for Personal Name Use (Inmyeong-yong Chuga Hanja-pyo; 인명용 추가 한자표; 人名用追加漢字表) that restricts the possible Hanja in new South Korean given names. Originally the list included the 1,800 Basic Hanja for Educational Use (Hanmun Gyoyuk-yong Gicho Hanja; 한문 교육용 기초 한자; 漢文敎育用基礎漢字) taught in middle and high school plus 1,054 additional characters; since then, the list has been expanded.

While the traditional practice is still largely followed, since the late 1970s, some people have given names that are native Korean words, usually of two syllables. Popular native Korean given names include Haneul (하늘; "Heaven" or "Sky") and Iseul (이슬; "Dew"). Despite the general trend away from traditional practice, people's names are still recorded in both Hangul and Hanja (if available) on official documents, in family genealogies, and so on.

Few people have one- or three-character given names, like the politicians Kim Gu and Goh Kun on the one hand, and Yeon Gaesomun on the other. People with two-character family names often have a one-character given name, like the singer Seomoon Tak.

Historical names

Native names

Prior to the adoption of Chinese-style names, Koreans had indigenous names, which were transcribed in Hanja. They did not have family names, at least as part of personal names. Native given names were sometimes composed of three syllables like Misaheun (미사흔; 未斯欣) and Sadaham (사다함; 斯多含).

Under the strong influence of Chinese culture in the first millennium of the Common Era, Koreans adopted family names. Family names were limited to kings and aristocrats at the beginning, but gradually spread to the commoners during the Goryeo and Joseon dynasty periods.

Goguryeo in Manchuria and northern Korea and Baekje in southwestern Korea had many non-Chinese family names. They often consisted of two characters and many of them seem to have been toponyms. Judging from Japanese records, some characters were pronounced not by their Chinese reading but by their reading in the native language (see Hanja#Hun and Eum). For example, Goguryeo General Yeon Gaesomun (연개소문; 淵蓋蘇文) is called Iri Kasumi (伊梨柯須弥) in Nihonshoki. Like cheon (천; 泉) in Chinese, iri would presumably have meant "fountain" in the Goguryeo language.

In contrast, Silla family names were totally Chinese-style ones, which is not likely related to King Muyeol's Sinicization policy.

The ancient kings of Korea gave their subjects family names. For example, in AD 33, King Yuri gave the tribes of Saro (Silla) names like Bae (배), Choe (최), Jeong (정), Son (손) and Seol (설). Other names given by kings are An (안), Cha (차), Han (한), Hong (홍), Kim (김), Kwon (권), Nam (남), Eo (어), and Wang (왕).

Mongolian names

Under the domination of the Mongol Empire during the Goryeo Dynasty, Korean kings and aristocrats had both Mongolian and Sino-Korean names. For example, King Gongmin had both the Mongolian name Bayan Temür (伯顏帖木兒) and the Chinese-style name Wang Gi (王祺) (later renamed Wang Jeon 王顓).

Mongolian personal names did not include family names, so some Korean nobility had names that were combinations of Sino-Korean family names and Mongolian given names. For example, Gi Cheol (奇轍), a brother of the Qi Empress, was called Gi Bayan Bukha (奇伯顏不花), and the Qi Empress's eunuch was called Bak Bukha (朴不花).

Japanization of names

During the period of Japanese colonial rule of Korea (1910–1945), Koreans were in practice compelled to adopt Japanese-language names. In 1939, as part of Governor-General Jiro Minami's policy of cultural assimilation (同化政策; dōka seisaku) , Ordinance No. 20 (Commonly called the "Name Order") was issued, and went into law on February 11, 1940, the 2,600th anniversary of the mythical Emperor Jimmu's founding of Japan .

The ordinance — commonly called Sōshi-kaimei (創氏改名) in Japanese — in theory allowed (but in practice compelled) Koreans to adopt Japanese family and given names. Although the Japanese Government-General officially prohibited compulsion, low-level officials practically forced Koreans to get Japanese-style family names, and by 1944, approximately 84 percent of the population had registered Japanese family names (Nahm 1988, p. 233).

Sōshi (Japanese) means the creation of a Japanese family name or si (Korean ssi (씨)), distinct from a Korean family name or seong (Japanese sei). Japanese family names represent the families they belong to and can be changed by marriage and other procedures, while Korean family names represent paternal linkages and are unchangeable. Sōshi represented a dual operation of both Japanese and Korean family name systems. Japanese policy dictated that Koreans either could register a completely new Japanese family name unrelated to their Korean surname, or have their Korean family name, in Japanese form, automatically become their Japanese name. Koreans were not, however, permitted to register a Korean family name other than their original name. For example, a person surnamed Bak (박; 朴) would be permitted to register Arai (新井), a Japanese name, or Paku (the Japanese equivalent of Bak), but did not have the choice of taking the name Kim (김; 金).

Japanese conventions of creating given names also made their way into Korea, such as putting a character "子" (Japanese ko and Korean ja meaning "descendant" or "son") to make feminine names like "玉子" (Japanese Tamako and Korean Okja), although this practice is seldom seen in modern Korea, either North or South. (See External links for more on the Sōshi-kaimei policy.)

After the Japanese defeat in World War II and the liberation of Korea, the Name Restoration Order (조선 성명 복구령; 朝鮮姓名復舊令) was issued on October 23, 1946 by the United States military administration south of the 38th parallel north, enabling Koreans to restore their Korean names if they wished to.

References

- Nahm, Andrew C. (1988). Korea: Tradition and Transformation — A History of the Korean People. Elizabeth, NJ: Hollym International. ISBN 0930878566

See also

- Name

- Chinese name

- Japanese name

- Vietnamese name

- Courtesy name

- Era name

- Generation name

- Posthumous name

- Temple name

- List of Korea-related topics

- List of most common surnames

- List of Korean family names

External links

- Table of Hanja for Personal Name Use

- Examples of Koreans who used Japanese names (in Japanese): by Saga Women's Junior College

- Public Figures in Popular Culture: Identity Problems of Minority Heroes — Footnote 16 gives bibliographic references for Korean perspectives on the Soshi-Kaimei policy.