This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Juvrud (talk | contribs) at 01:42, 27 April 2015. The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 01:42, 27 April 2015 by Juvrud (talk | contribs)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) "Haakon I" redirects here. For the King of Sweden, see Haakon I of Sweden.| Some of this article's listed sources may not be reliable. Please help improve this article by looking for better, more reliable sources. Unreliable citations may be challenged and removed. (March 2011) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

| Haakon I the Good | |

|---|---|

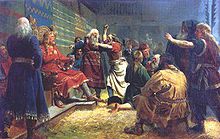

Haakon the Good, by Peter Nicolai Arbo Haakon the Good, by Peter Nicolai Arbo | |

| King of Norway | |

| Reign | 934–961 |

| Predecessor | Eric I |

| Successor | Harald II |

| Born | c. 920 Håkonshella, Hordaland, Norway |

| Died | 961 Håkonshella, Hordaland (fatally wounded in the Battle of Fitjar) |

| Burial | Seim, Hordaland, Norway |

| Issue | Thora |

| House | Fairhair dynasty |

| Father | Harald Fairhair |

| Mother | Thora Mosterstong |

| Religion | Norse paganism, Roman Catholicism |

Haakon Haraldsson (c. 920–961), also known as Haakon the Good (Old Norse: Hákon góði, Norwegian: Håkon den gode) and sometimes Haakon Adalsteinfostre (Old Norse: Hákon Aðalsteinsfóstri, Norwegian: Håkon Adalsteinsfostre), was the third king of Norway and the youngest son of Harald Fairhair and Thora Mosterstang.

Early life

King Harald determined to remove his youngest son out of harm's way and accordingly sent him to the court of King Athelstan of England. Haakon was fostered by King Athelstan, as part of a peace agreement made by his father, for which reason Haakon was nicknamed Adalsteinfostre. The English court introduced him in the Christian religion. On the news of his father's death, King Athelstan provided Haakon with ships and men for an expedition against his half-brother Eirik Bloodaxe, who had been proclaimed king.

Reign

At his arrival back in Norway, Haakon gained the support of the landowners by promising to give up the rights of taxation claimed by his father over inherited real property. Eirik Bloodaxe soon found himself deserted on all sides, and saved his own and his family's lives by fleeing from the country. Eirik fled to the Orkney Islands and later to the Kingdom of Jorvik, eventually meeting a violent death at Stainmore, Westmorland, in 954 along with his son, Haeric.

In 953, Haakon had to fight a fierce battle (Slaget på Blodeheia ved Avaldsnes) at Avaldsnes against the sons of Eirik Bloodaxe. Haakon won the battle at which Eirik's son Guttorm died. One of Haakon's most famous victories was the Battle of Rastarkalv (Slaget på Rastarkalv) near Frei in 955. By placing ten standards far apart along a low ridge, he gave the impression that his army was bigger than it actually was. He managed to fool Eirik’s sons into believing that they were out-numbered. The Danes fled and were slaughtered by Haakon’s army. The sons of Eirik returned in 957, with support from the Danish king, Gorm the Old. But again they were defeated by Haakon's effective army system.

Haakon was frequently successful in battle but not in his attempts to introduce Christianity, which aroused an opposition he did not feel strong enough to face. So entirely did even his immediate circle ignore his religion that his court poet, Eyvindr Skáldaspillir, composed the poem Hákonarmál upon his death, representing his reception by the Norse gods into Valhalla.

Succession

Three of the sons of Eirik Bloodaxe (Gamle, Harold, and Sigurd) landed unnoticed on Hordaland in 961 and surprised the king at his residence in Fitjar. Haakon was mortally wounded at the Battle of Fitjar (Slaget ved Fitjar) after a final victory over Eirik’s sons. The King’s arm was pierced by an arrow and he died later from his wounds. He was buried in the burial mound (Håkonshaugen) in the village of Seim in Lindås municipality in the county of Hordaland. After Haakon's death, Harald Greycloak, third son of Eirik Bloodaxe, jointly with his brothers became kings of Norway. However, they had little authority outside Western Norway. Harald, by being the oldest, was the most powerful of the brothers. The succession issue was settled when he ascended the throne as Harald II. Subsequently the Norwegians were tormented by years of war. In 970, King Harald II was tricked into coming to Denmark and killed in a plot planned by Sigurd Haakonsson's son Haakon Sigurdsson, who had become an ally of Harald Bluetooth.

Modern references

- Haakon’s Park (Håkonarparken) opposite Fitjar Church is the location of a statue of King Haakon sculpted by Anne Grimdalen. The statue was erected during 1961 at the one thousand year commemoration of the Battle of Fitjar.

- Håkonarspelet is a historical play writen by Johannes Heggland in 1997.

- Haakon is a major character in Mother of Kings by Poul Anderson.

- Haakon is the protagonist in God's Hammer by Eric Schumacher .

Ancestors from the sagas

| Ancestry of Haakon the Good given in the sagas - many connections are dubious | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- "Haakon I". The Free Dictionary.

- "Hakon the Good". Catholic Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2007-02-18.

- Haakon the Good and the Sons of Gunhild (Yesterday's Classics, LLC)

- Håkon den godes landskap på Frei og slaget på Rastarkalv (Siw Helen Myrvoll Grønland. Department of Linguistics and Scandinavian Studies. University of Oslo. 2014)

- Hákonarmál (Heimskringla.no)

- King Haakon The Good of Norway buried at Saeheim

- Håkonarparken (visitsunnhordland.no)

- Kongen med gullhjelmen (Håkonarspelet)

- Mother of Kings by Poul Anderson. (New York: Tor/Forge 2001) ISBN 0-765-34502-1

- God's Hammer by Eric Schumacher. (Paul Mould Publishing. 2nd edition, 2005) ISBN 978-1586900175

External links

- "Haakon" . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.