This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Kendall-K1 (talk | contribs) at 11:15, 22 September 2015 (rvv). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 11:15, 22 September 2015 by Kendall-K1 (talk | contribs) (rvv)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) For the pistol cartridge ranking system, see Power factor (pistol).In electrical engineering, the power factor of an AC electrical power system is defined as the ratio of the real power flowing to the load to the apparent power in the circuit, and is a dimensionless number in the closed interval of -1 to 1. A power factor of less than one means that the voltage and current waveforms are not in phase, reducing the instantaneous product of the two waveforms (V x I). Real power is the capacity of the circuit for performing work in a particular time. Apparent power is the product of the current and voltage of the circuit. Due to energy stored in the load and returned to the source, or due to a non-linear load that distorts the wave shape of the current drawn from the source, the apparent power will be greater than the real power. A negative power factor occurs when the device (which is normally the load) generates power, which then flows back towards the source, which is normally considered the generator.

In an electric power system, a load with a low power factor draws more current than a load with a high power factor for the same amount of useful power transferred. The higher currents increase the energy lost in the distribution system, and require larger wires and other equipment. Because of the costs of larger equipment and wasted energy, electrical utilities will usually charge a higher cost to industrial or commercial customers where there is a low power factor.

Linear loads with low power factor (such as induction motors) can be corrected with a passive network of capacitors or inductors. Non-linear loads, such as rectifiers, distort the current drawn from the system. In such cases, active or passive power factor correction may be used to counteract the distortion and raise the power factor. The devices for correction of the power factor may be at a central substation, spread out over a distribution system, or built into power-consuming equipment.

Linear circuits

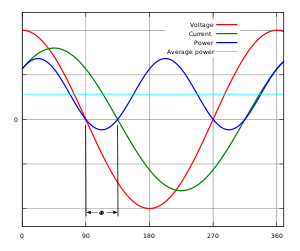

In a purely resistive AC circuit, voltage and current waveforms are in step (or in phase), changing polarity at the same instant in each cycle. All the power entering the load is consumed (or dissipated).

Where reactive loads are present, such as with capacitors or inductors, energy storage in the loads results in a phase difference between the current and voltage waveforms. During each cycle of the AC voltage, extra energy, in addition to any energy consumed in the load, is temporarily stored in the load in electric or magnetic fields, and then returned to the power grid a fraction of the period later.

Because HVAC distribution systems are essentially quasi-linear circuit systems subject to continuous daily variation, there is a continuous "ebb and flow" of nonproductive power. Non productive power increases the current in the line, potentially to the point of failure.

Thus, a circuit with a low power factor will use higher currents to transfer a given quantity of real power than a circuit with a high power factor. A linear load does not change the shape of the waveform of the current, but may change the relative timing (phase) between voltage and current.

Electrical circuits containing purely resistive heating elements (filament lamps, cooking stoves, etc.) have a power factor around 1.0, but circuits containing inductive or capacitive elements (electric motors, solenoid valves, lamp ballasts, and others) often have a power factor below 1.

Definition and calculation

AC power flow has three components:

- Real power or active power (P), expressed in watts (W)

- Apparent power (S), usually expressed in volt-amperes (VA)

- Reactive power (Q), usually expressed in reactive volt-amperes (var)

The VA and var are non-SI units mathematically identical to the Watt, but are used in engineering practice instead of the Watt in order to state what quantity is being expressed. The SI explicitly disallows using units for this purpose or as the only source of information about a physical quantity as used.

The power factor is defined as:

In the case of a perfectly sinusoidal waveform, P, Q and S can be expressed as vectors that form a vector triangle:

If is the phase angle between the current and voltage, then the power factor is equal to the cosine of the angle, :

Since the units are consistent, the power factor is by definition a dimensionless number between −1 and 1. When power factor is equal to 0, the energy flow is entirely reactive and stored energy in the load returns to the source on each cycle. When the power factor is 1, all the energy supplied by the source is consumed by the load. Power factors are usually stated as "leading" or "lagging" to show the sign of the phase angle. Capacitive loads are leading (current leads voltage), and inductive loads are lagging (current lags voltage).

If a purely resistive load is connected to a power supply, current and voltage will change polarity in step, the power factor will be unity (1), and the electrical energy flows in a single direction across the network in each cycle. Inductive loads such as transformers and motors (any type of wound coil) consume reactive power with current waveform lagging the voltage. Capacitive loads such as capacitor banks or buried cable generate reactive power with current phase leading the voltage. Both types of loads will absorb energy during part of the AC cycle, which is stored in the device's magnetic or electric field, only to return this energy back to the source during the rest of the cycle.

For example, to get 1 kW of real power, if the power factor is unity, 1 kVA of apparent power needs to be transferred (1 kW ÷ 1 = 1 kVA). At low values of power factor, more apparent power needs to be transferred to get the same real power. To get 1 kW of real power at 0.2 power factor, 5 kVA of apparent power needs to be transferred (1 kW ÷ 0.2 = 5 kVA). This apparent power must be produced and transmitted to the load in the conventional fashion, and is subject to the usual distributed losses in the production and transmission processes.

Electrical loads consuming alternating current power consume both real power and reactive power. The vector sum of real and reactive power is the apparent power. The presence of reactive power causes the real power to be less than the apparent power, and so, the electric load has a power factor of less than 1.

A negative power factor (0 to -1) can result from returning power to the source, such as in the case of a building fitted with solar panels when their power is not being fully utilised within the building and the surplus is fed back into the supply.

Power factor correction of linear loads

A high power factor is generally desirable in a transmission system to reduce transmission losses and improve voltage regulation at the load. It is often desirable to adjust the power factor of a system to near 1.0. When reactive elements supply or absorb reactive power near the load, the apparent power is reduced. Power factor correction may be applied by an electric power transmission utility to improve the stability and efficiency of the transmission network. Individual electrical customers who are charged by their utility for low power factor may install correction equipment to reduce those costs.

Power factor correction brings the power factor of an AC power circuit closer to 1 by supplying reactive power of opposite sign, adding capacitors or inductors that act to cancel the inductive or capacitive effects of the load, respectively. For example, the inductive effect of motor loads may be offset by locally connected capacitors. If a load had a capacitive value, inductors (also known as reactors in this context) are connected to correct the power factor. In the electricity industry, inductors are said to consume reactive power and capacitors are said to supply it, even though the energy is just moving back and forth on each AC cycle.

The reactive elements can create voltage fluctuations and harmonic noise when switched on or off. They will supply or sink reactive power regardless of whether there is a corresponding load operating nearby, increasing the system's no-load losses. In the worst case, reactive elements can interact with the system and with each other to create resonant conditions, resulting in system instability and severe overvoltage fluctuations. As such, reactive elements cannot simply be applied without engineering analysis.

An automatic power factor correction unit consists of a number of capacitors that are switched by means of contactors. These contactors are controlled by a regulator that measures power factor in an electrical network. Depending on the load and power factor of the network, the power factor controller will switch the necessary blocks of capacitors in steps to make sure the power factor stays above a selected value.

Instead of using a set of switched capacitors, an unloaded synchronous motor can supply reactive power. The reactive power drawn by the synchronous motor is a function of its field excitation. This is referred to as a synchronous condenser. It is started and connected to the electrical network. It operates at a leading power factor and puts vars onto the network as required to support a system's voltage or to maintain the system power factor at a specified level.

The condenser's installation and operation are identical to large electric motors. Its principal advantage is the ease with which the amount of correction can be adjusted; it behaves like an electrically variable capacitor. Unlike capacitors, the amount of reactive power supplied is proportional to voltage, not the square of voltage; this improves voltage stability on large networks. Synchronous condensers are often used in connection with high-voltage direct-current transmission projects or in large industrial plants such as steel mills.

For power factor correction of high-voltage power systems or large, fluctuating industrial loads, power electronic devices such as the Static VAR compensator or STATCOM are increasingly used. These systems are able to compensate sudden changes of power factor much more rapidly than contactor-switched capacitor banks, and being solid-state require less maintenance than synchronous condensers.

Non-linear loads

Examples of non-linear loads on a power system are rectifiers (such as used in a power supply), and arc discharge devices such as fluorescent lamps, electric welding machines, or arc furnaces. Because current in these systems is interrupted by a switching action, the current contains frequency components that are multiples of the power system frequency. Distortion power factor is a measure of how much the harmonic distortion of a load current decreases the average power transferred to the load.

Non-sinusoidal components

Non-linear loads change the shape of the current waveform from a sine wave to some other form. Non-linear loads create harmonic currents in addition to the original (fundamental frequency) AC current. Filters consisting of linear capacitors and inductors can prevent harmonic currents from entering the supplying system.

In linear circuits having only sinusoidal currents and voltages of one frequency, the power factor arises only from the difference in phase between the current and voltage. This is "displacement power factor". This is of importance in practical power systems that contain non-linear loads such as rectifiers, some forms of electric lighting, electric arc furnaces, welding equipment, switched-mode power supplies and other devices.

A typical multimeter will give incorrect results when attempting to measure the AC current in a non-sinusoidal waveform; the instruments sense the average value of the rectified waveform. The average response is then calibrated to the effective RMS value. An RMS sensing multimeter must be used to measure the actual RMS currents and voltages (and therefore apparent power). To measure the real power or reactive power, a wattmeter designed to work properly with non-sinusoidal currents must be used.

Distortion power factor

The distortion power factor describes how the harmonic distortion of a load current decreases the average power transferred to the load.

is the total harmonic distortion of the load current. is the fundamental component of the current and is the total current – both are root mean square-values (distortion power factor can also be used to describe individual order harmonics, using the corresponding current in place of total current). This definition with respect to total harmonic distortion assumes that the voltage stays undistorted (sinusoidal, without harmonics). This simplification is often a good approximation for stiff voltage sources (not being affected by changes in load downstream in the distribution network). Total harmonic distortion of typical generators from current distortion in the network is on the order of 1–2%, which can have larger scale implications but can be ignored in common practice.

The result when multiplied with the displacement power factor (DPF) is the overall, true power factor or just power factor (PF):

Distortion in three-phase networks

In practice, the local effects of distortion current on devices in a three-phase distribution network rely on the magnitude of certain order harmonics rather than the total harmonic distortion.

For example, the triplen, or zero-sequence, harmonics (3rd, 9th, 15th, etc.) have the property of being in-phase when compared line-to-line. In a delta-wye transformer, these harmonics can result in circulating currents in the delta windings and result in greater resistive heating. In a wye-configuration of a transformer, triplen harmonics will not create these currents, but they will result in a non-zero current in the neutral wire. This could overload the neutral wire in some cases and create error in kilowatt-hour metering systems and billing revenue. The presence of current harmonics in a transformer also result in larger eddy currents in the magnetic core of the transformer. Eddy current losses generally increase as the square of the frequency, lowering the transformer's efficiency, dissipating additional heat, and reducing its service life.

Negative-sequence harmonics (5th, 11th, 17th, etc.) combine 120 degrees out of phase, similarly to the fundamental harmonic but in a reversed sequence. In generators and motors, these currents produce magnetic fields which oppose the rotation of the shaft and sometimes result in damaging mechanical vibrations.

Switched-mode power supplies

Main article: switched-mode power supply § Power factorA particularly important class of non-linear loads is the millions of personal computers that typically incorporate switched-mode power supplies (SMPS) with rated output power ranging from a few watts to more than 1 kW. Historically, these very-low-cost power supplies incorporated a simple full-wave rectifier that conducted only when the mains instantaneous voltage exceeded the voltage on the input capacitors. This leads to very high ratios of peak-to-average input current, which also lead to a low distortion power factor and potentially serious phase and neutral loading concerns.

A typical switched-mode power supply first converts the AC mains to a DC bus by means of a bridge rectifier or a similar circuit. The output voltage is then derived from this DC bus. The problem with this is that the rectifier is a non-linear device, so the input current is highly non-linear. That means that the input current has energy at harmonics of the frequency of the voltage.

This presents a particular problem for the power companies, because they cannot compensate for the harmonic current by adding simple capacitors or inductors, as they could for the reactive power drawn by a linear load. Many jurisdictions are beginning to legally require power factor correction for all power supplies above a certain power level.

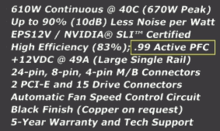

Regulatory agencies such as the EU have set harmonic limits as a method of improving power factor. Declining component cost has hastened implementation of two different methods. To comply with current EU standard EN61000-3-2, all switched-mode power supplies with output power more than 75 W must include passive power factor correction, at least. 80 Plus power supply certification requires a power factor of 0.9 or more.

Power factor correction (PFC) in non-linear loads

Passive PFC

The simplest way to control the harmonic current is to use a filter that passes current only at line frequency (50 or 60 Hz). The filter consists of capacitors or inductors, and makes a non-linear device look more like a linear load. An example of passive PFC is a valley-fill circuit.

A disadvantage of passive PFC is that it requires larger inductors or capacitors than an equivalent power active PFC circuit. Also, in practice, passive PFC is often less effective at improving the power factor.

Active PFC

Active PFC is the use of power electronics to change the waveform of current drawn by a load to improve the power factor. Some types of the active PFC are buck, boost, buck-boost and synchronous condenser. Active power factor correction can be single-stage or multi-stage.

In the case of a switched-mode power supply, a boost converter is inserted between the bridge rectifier and the main input capacitors. The boost converter attempts to maintain a constant DC bus voltage on its output while drawing a current that is always in phase with and at the same frequency as the line voltage. Another switched-mode converter inside the power supply produces the desired output voltage from the DC bus. This approach requires additional semiconductor switches and control electronics, but permits cheaper and smaller passive components. It is frequently used in practice.

SMPSs with passive PFC can achieve power factor of about 0.7–0.75, SMPSs with active PFC, up to 0.99 power factor, while a SMPSs without any power factor correction have a power factor of only about 0.55–0.65.

Due to their very wide input voltage range, many power supplies with active PFC can automatically adjust to operate on AC power from about 100 V (Japan) to 230 V (Europe). That feature is particularly welcome in power supplies for laptops.

Dynamic PFC

Dynamic power factor correction (DPFC), sometimes referred to as "real-time power factor correction," is used for electrical stabilization in cases of rapid load changes (e.g. at large manufacturing sites). DPFC is useful when standard power factor correction would cause over or under correction. DPFC uses semiconductor switches, typically thyristors, to quickly connect and disconnect capacitors or inductors from the network in order to improve power factor.

Importance of power factor in distribution systems

Power factors below 1.0 require a utility to generate more than the minimum volt-amperes necessary to supply the real power (watts). This increases generation and transmission costs. For example, if the load power factor were as low as 0.7, the apparent power would be 1.4 times the real power used by the load. Line current in the circuit would also be 1.4 times the current required at 1.0 power factor, so the losses in the circuit would be doubled (since they are proportional to the square of the current). Alternatively all components of the system such as generators, conductors, transformers, and switchgear would be increased in size (and cost) to carry the extra current.

Utilities typically charge additional costs to commercial customers who have a power factor below some limit, which is typically 0.9 to 0.95. Engineers are often interested in the power factor of a load as one of the factors that affect the efficiency of power transmission.

With the rising cost of energy and concerns over the efficient delivery of power, active PFC has become more common in consumer electronics. Current Energy Star guidelines for computers call for a power factor of ≥ 0.9 at 100% of rated output in the PC's power supply. According to a white paper authored by Intel and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, PCs with internal power supplies will require the use of active power factor correction to meet the ENERGY STAR 5.0 Program Requirements for Computers.

In Europe, EN 61000-3-2 requires power factor correction be incorporated into consumer products.

Techniques for measuring the power factor

The power factor in a single-phase circuit (or balanced three-phase circuit) can be measured with the wattmeter-ammeter-voltmeter method, where the power in watts is divided by the product of measured voltage and current. The power factor of a balanced polyphase circuit is the same as that of any phase. The power factor of an unbalanced poly phase circuit is not uniquely defined.

A direct reading power factor meter can be made with a moving coil meter of the electrodynamic type, carrying two perpendicular coils on the moving part of the instrument. The field of the instrument is energized by the circuit current flow. The two moving coils, A and B, are connected in parallel with the circuit load. One coil, A, will be connected through a resistor and the second coil, B, through an inductor, so that the current in coil B is delayed with respect to current in A. At unity power factor, the current in A is in phase with the circuit current, and coil A provides maximum torque, driving the instrument pointer toward the 1.0 mark on the scale. At zero power factor, the current in coil B is in phase with circuit current, and coil B provides torque to drive the pointer towards 0. At intermediate values of power factor, the torques provided by the two coils add and the pointer takes up intermediate positions.

Another electromechanical instrument is the polarized-vane type. In this instrument a stationary field coil produces a rotating magnetic field, just like a polyphase motor. The field coils are connected either directly to polyphase voltage sources or to a phase-shifting reactor if a single-phase application. A second stationary field coil, perpendicular to the voltage coils, carries a current proportional to current in one phase of the circuit. The moving system of the instrument consists of two vanes that are magnetized by the current coil. In operation the moving vanes take up a physical angle equivalent to the electrical angle between the voltage source and the current source. This type of instrument can be made to register for currents in both directions, giving a four-quadrant display of power factor or phase angle.

Digital instruments can be made that either directly measure the time lag between voltage and current waveforms and so calculate the power factor, or that measure both true and apparent power in the circuit and calculate the quotient. The first method is only accurate if voltage and current are sinusoidal. Loads such as rectifiers distort the waveforms from the sinusoidal shape.

Mnemonics

English-language power engineering students are advised to remember: "ELI the ICE man" or "ELI on ICE" – the voltage E leads the current I in an inductor L; the current leads the voltage in a capacitor C.

Another common mnemonic is CIVIL – in a capacitor (C) the current (I) leads voltage (V), voltage (V) leads current (I) in an inductor (L).

References

- Authoritative Dictionary of Standards Terms (7th ed.), IEEE, ISBN 0-7381-2601-2, Std. 100.

- Trial-Use Standard Definitions for the Measurement of Electric Power Quantities Under Sinusoidal, Nonsinusoidal, Balanced, or Unbalanced Conditions, IEEE, 2000, ISBN 0-7381-1963-6, Std. 1459-2000. Note 1, section 3.1.1.1, when defining the quantities for power factor, asserts that real power only flows to the load and can never be negative. As of 2013, one of the authors acknowledged that this note was incorrect, and is being revised for the next edition. See http://powerstandards.com/Shymanski/draft.pdf

- Duddell, W. (1901), "On the resistance and electromotive forces of the electric arc", Proceedings, The Royal Society of London: 512–15,

The fact that the solid arc has, at low frequencies, a negative power factor, indicates that the arc is supplying power to the alternator…

- Zhang, S. (July 2006), "Analysis of some measurement issues in bushing power factor tests in the field", Trans Pwr Del, 21 (3), IEEE: 1350–56, doi:10.1109/tpwrd.2006.874616,

…(the measurement) gives both negative power factor and negative resistive current (power loss).

- Almarshoud, A. F. (2004), "Performance of Grid-Connected Induction Generator under Naturally Commutated AC Voltage Controller", Electric Power Components and Systems, 32 (7), et al,

Accordingly, the generator will consume active power from the grid, which leads to negative power factor.

- "SI Units – Electricity and Magnetism". CH: International Electrotechnical Commission. Archived from the original on 2007-12-11. Retrieved 2013-06-14.

- The International System of Units (SI) [SI brochure] (PDF). § 5.3.2 (p. 132, 40 in the PDF file): BIPM. 2006.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - Ewald Fuchs; Mohammad A. S. Masoum (14 July 2015). Power Quality in Power Systems and Electrical Machines. Elsevier Science. pp. 432–. ISBN 978-0-12-800988-8.

The DPF it the cosine of the angle between these two quantities

- J. B. Dixit; Amit Yadav (1 January 2010). Electrical Power Quality. Laxmi Publications, Ltd. pp. 123–. ISBN 978-93-80386-74-4.

- Sankaran, C. (1999), Effects of Harmonics on Power Systems, Electro-Test,

...and voltage-time relationship deviates from the pure sine function. The distortion at the point of generation is very small (about 1% to 2%), but nonetheless it exists.

- "Single-phase load harmonics vs. three-phase load harmonics", Power System Harmonics (PDF), Pacific Gas and Electric.

- "Harmonic Effects", Harmonics and IEEE 519 (PDF), CA: EnergyLogix Solutions.

- Sankaran, C. (1999), "Transformers", Effects of Harmonics on Power Systems, Electro-Test.

- Sankaran, C. (1999), "Motors", Effects of Harmonics on Power Systems, Electro-Test,

The interaction between the positive and negative sequence magnetic fields and currents produces torsional oscillations of the motor shaft. These oscillations result in shaft vibrations.

- "What is an 80 PLUS certified power supply?", Certified Power Supplies and Manufacturers, 80 Plus

- Schramm, Ben (Fall 2006), "Power Supply Design Principles: Techniques and Solutions, Part 3", Newsletter, Nuvation

- "Quasi-active power factor correction with a variable inductive filter: theory, design and practice", Xplore, IEEE.

- Wölfle, W. H.; Hurley, W. G., "Quasi-active Power Factor Correction: The Role of Variable Inductance", Power electronics (project), IE: Nuigalway

- ATX Power Supply Units Roundup, xBit labs,

The power factor is the measure of reactive power. It is the ratio of active power to the total of active and reactive power. It is about 0.65 with an ordinary PSU, but PSUs with active PFC have a power factor of 0.97–0.99. hardware reviewers sometimes make no difference between the power factor and the efficiency factor. Although both these terms describe the effectiveness of a power supply, it is a gross mistake to confuse them. There is a very small effect from passive PFC – the power factor grows only from 0.65 to 0.7–0.75.

- The Active PFC Market is Expected to Grow at an Annually Rate of 12.3% Till 2011, Find articles, Mar 16, 2006,

Higher-powered products are also likely to use active PFC, since it would be the most cost effective way to bring products into compliance with the EN standard.

- Power Factor Correction, TECHarp,

Passive PFC the power factor is low at 60–80%. Active PFC ... a power factor of up to 95%

. - Why we need PFC in PSU, Silverstone Technology,

Normally, the power factor value of electronic device without power factor correction is approximately 0.5. Passive PFC 70~80% Active PFC 90~99.9%

. - Brooks, Tom (Mar 2004), "PFC options for power supplies", Taiyo, Electronic products,

The disadvantages of passive PFC techniques are that they typically yield a power factor of only 0.60 to 0.70 Dual-stage active PFC technology a power factor typically greater than 0.98

. - Power Factor Correction (PFC) Basics (PDF) (application note), Fairchild Semiconductor, 2004.

- Sugawara, I.; Suzuki, Y.; Takeuchi, A.; Teshima, T. (19–23 Oct 1997), "Experimental studies on active and passive PFC circuits", INTELEC 97, 19th International Telecommunications Energy Conference, pp. 571–78, doi:10.1109/INTLEC.1997.646051

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link). - Chavez, C.; Houdek, J. A. (9–11 Oct 2007). "Dynamic Harmonic Mitigation and power factor correction". IEE. Electrical Power Quality. doi:10.1109/EPQU.2007.4424144.

- Power Factor Correction Handbook (PDF), ON Semiconductor, 2007.

- Program Requirements for Computers (PDF) (Version 5.0 ed.), US: Energy Star.

- Bolioli, T.; Duggirala, M.; Haines, E.; Kolappan, R.; Wong, H. (2009), Version 5.0 System Implementation (PDF) (white paper), Energy Star.

- Fink, Donald G.; Beaty, H. Wayne (1978), Standard Handbook for Electrical Engineers (11 ed.), New York: McGraw-Hill, p. 3‐29 paragraph 80, ISBN 0-07-020974-X

- Manual of Electric Instruments Construction and Operating Principles, Schenectady, New York: General Electric, Meter and Instrument Department, 1949, pp. 66–68, GET-1087A

External links

- Harmonics and how they relate to power factor (PDF), U Texas.

- NIST Team Demystifies Utility of Power Factor Correction Devices, NIST, December 15, 2009.

- Power factor calculation and correction, US.

,

,  ). The blue line shows all the power is stored temporarily in the load during the first quarter cycle and returned to the grid during the second quarter cycle, so no real power is consumed.

). The blue line shows all the power is stored temporarily in the load during the first quarter cycle and returned to the grid during the second quarter cycle, so no real power is consumed. ,

,  ). The blue line shows some of the power is returned to the grid during the part of the cycle labeled

). The blue line shows some of the power is returned to the grid during the part of the cycle labeled  .

.

:

:

is the

is the  is the fundamental component of the current and

is the fundamental component of the current and  is the total current – both are

is the total current – both are