This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Curly Turkey (talk | contribs) at 23:51, 27 September 2015. The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 23:51, 27 September 2015 by Curly Turkey (talk | contribs)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)

| Kobayashi Kiyochika | |

|---|---|

| 小林清親 | |

| |

| Born | Kobayashi Katsunosuke (1847-09-10)September 10, 1847 Edo, Japan |

| Died | November 28, 1915(1915-11-28) (aged 68) Tokyo, Japan |

| Nationality | Japanese |

| Movement | ukiyo-e |

Kobayashi Kiyochika (小林 清親, 10 September 1847 – 28 November 1915) was a Japanese ukiyo-e artist of the Meiji period.

Kiyochika is best known for his prints of scenes around Tokyo which reflect the transformations of modernity. He has been described as "the last important ukiyo-e master and the first noteworthy print artist of modern Japan... an anachronistic survival from an earlier age, a minor hero whose best efforts to adapt ukiyo-e to the new world of Meiji Japan were not quite enough".

Life and career

Kiyochika was born Kobayashi Katsunosuke (小林 勝之助) on 10 September 1847 (the first day of the eighth month of the ninth year of Kōka on the Japanese calendar) in Kurayashiki [ja] neighbourhood of Honjo in Edo (modern Tokyo). His father was Kobayashi Mohē (茂兵衛), who worked as a a minor official in charge of unloading rice collected as taxes. His mother Chikako (知加子) was the daughter of another such official, Matsui Yasunosuke (松井安之助). The 1855 Edo earthquake destroyed the family home but left the family unharmed.

Though the youngest of his parents' nine children, Kiyochika took over as head of the household upon his father's death in 1862 and changed his name from Katsunosuke. As a subordinate to a kanjō-bugyō official Kiyochika travelled to Kyoto in 1865 with Tokugawa Iemochi's retinue, the first shogunal visit to Kyoto in over two centuries. They continued to Osaka, where Kiyochika thereafter made his home. During the Boshin War in 1868 Kiyochika participated on the side of the shogun in the Battle of Toba–Fushimi in Kyoto and returned to Osaka after defeat of the shogun's forces. He returned by land to Edo and re-entered the employ of the shogun. After the fall of Edo he relocated to Shizuoka, the heartland of the Tokugawa clan, where he stayed for the next several years.

Kiyochika returned to the renamed Tokyo in May 1873 with his mother, who died there that September. He began to concentrate on art and associated with such artists as Shibata Zeshin and Kawanabe Kyōsai, under whom he may have studied painting. In 1875 he began producing series of ukiyo-e prints of the rapidly modernizing and Westernizing Tokyo and is said to have studied Western-style painting under Charles Wirgman. In August 1876 produced the first kōsen-ga [ja] (光線画, "light-ray pictures"), ukiyo-e prints employing Western-style naturalistc light and shade, possibly under the influence of the photography of Shimooka Renjō.

The son of a government official, Kiyochika was heavily influenced by Western art, which he studied under Charles Wirgman. He also based a lot of his work on Western etchings, lithographs, and photographs which became widely available in Japan in the Meiji period. Kiyochika also studied Japanese art under the great artists Kawanabe Kyōsai and Shibata Zeshin.

His woodblock prints stand apart from those of the earlier Edo period, incorporating not only Western styles but also Western subjects, as he depicted the introduction of such things as horse-drawn carriages, clock towers, and railroads to Tokyo. These show considerable influence from the landscapes of Hokusai and the work of Utagawa Kuniyoshi, but the Western influence is also unquestionable; these are much darker images on the whole, and share many features with Western lithographs and etchings of the time.

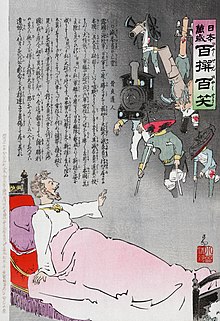

These were produced primarily from 1876 to 1881; Kiyochika would continue to publish ukiyo-e prints for the rest of his life, but also worked extensively in illustrations and sketches for newspapers, magazines, and books. He also produced a number of prints depicting scenes from the Sino-Japanese War and Russo-Japanese War, collaborating with caption writer Koppi Dojin, penname of Nishimori Takeki (1861-1913), to contribute a number of illustrations to the propaganda series Nihon banzai hyakusen hyakushō ("Long live Japan: 100 victories, 100 laughs").

In his later years Kiyochika devoted himself more to painting. His wife Yoshiko (芳子) died 13 April 1912. Kiyochika spent July to October 1915 in Nagano Prefecture and visited the Asama Onsen hot springs in Matsumoto to treat his rheumatism. On 28 November 1915 Kiyochika died at his Tokyo home in Nakazato, Kita Ward. His grave is at Ryūfuku-in Temple in Motoasakusa.

Style and analysis

| This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (September 2015) |

During the Edo period most ukiyo-e artists regularly produced shunga erotic pictures, despite government censorship. In the Meiji period censorship became stricter as the government wanted to present a Japan that met the moral expectations of the West, and production of shunga became scarce. Kiyochika is one of the artists not known to have produced any erotic art.

References

- Lane, Richard. (1978). Images from the Floating World, The Japanese Print, pp. 193–194.

- Lane, p. 193.

- ^ Kikkawa 2015, p. 203.

- ^ Meech-Pekarik 1986, p. 194.

- "Japan Holds the String When Russia Reaches to Grasp". World Digital Library. Retrieved 24 May 2013.

- Boscaro, Andrea et al. (1995). Rethinking Japan: Literature, Visual Arts & Linguistics, p. 135., p. 135, at Google Books

- ^ Merritt, Helen et al. (1995). Guide to Modern Japanese Woodblock Prints, 1900-1975, p.71., p. 71, at Google Books

- "Farewell Present of Useful White Flag, Which Russian General's Wife Thoughtfully Gives When He Leaves for Front, Telling Him to Use It As Soon As He Sees Japanese Army". World Digital Library. Retrieved 24 May 2013.

- "Kuropatkin Secures Safety - Your Flag Does Not Work, Try Another". World Digital Library. Retrieved 24 May 2013.

- Buckland 2013, p. 260.

Works cited

- Boscaro, Andrea; Franco Gatti and Massimo Raveri. (1990). Rethinking Japan: Literature, Visual Arts & Linguistics. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 9780312048198; ISBN 9780312048204; OCLC 21523936

- Buckland, Rosina (2013). . Japan Review (26): 259–76.

{{cite journal}}: Check|url=value (help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Katō, Yōsuke (2015). "小林清親の画業" [The works of Kobayashiu Kiyochika]. Kobayashi Kiyochika: Bunmei kaika no hikari to kage wo mitsumete 小林清親: 文明開化の光と影をみつめて [Kobayashi Kiyochika: Gazing at the light and shadow of Meiji-period modernization] (in Japanese). Seigensha. pp. 194–197. ISBN 978-4-86152-480-6.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|1=,|2=, and|3=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kikkawa, Hideki (2015). "小林清親年譜" [Kobayashi Kiyochika chronology]. Kobayashi Kiyochika: Bunmei kaika no hikari to kage wo mitsumete 小林清親: 文明開化の光と影をみつめて [Kobayashi Kiyochika: Gazing at the light and shadow of Meiji-period modernization] (in Japanese). Seigensha. pp. 203–205. ISBN 978-4-86152-480-6.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|1=,|2=, and|3=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lane, Richard (1978). Images from the Floating World: The Japanese Print. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780192114471. OCLC 5246796.

- Meech-Pekarik, Julia (1986). The World of the Meiji Print: Impressions of a New Civilization. Weatherhill. ISBN 978-0-8348-0209-4 – via Questia.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|subscription=ignored (|url-access=suggested) (help) - Merritt, Helen and Nanako Yamada. (1995). Guide to Modern Japanese Woodblock Prints, 1900-1975. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 9780824817329; ISBN 9780824812867; OCLC 247995392

- Yamamoto, Kazuko (2015). "浮世絵版画の死と再生―清親の評価の変遷" [The death and rebirth of ukiyo-e woodblock prints: changes in the assessment of Kiyochika]. Kobayashi Kiyochika: Bunmei kaika no hikari to kage wo mitsumete 小林清親: 文明開化の光と影をみつめて [Kobayashi Kiyochika: Gazing at the light and shadow of Meiji-period modernization] (in Japanese). Seigensha. pp. 198–202. ISBN 978-4-86152-480-6.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|1=,|2=, and|3=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help); Invalid|script-title=: missing prefix (help)

External links

- Shizuoka Prefectural Museum of Art

- Sino-Japanese War print exhibition at MIT

- Prints from Nihon banzai hyakusen hyakushō ("Long live Japan: 100 victories, 100 laughs")

- The Sino-Japanese War of 1894-1895: as seen in prints and archives (Gallery page) (British Library/Japan Center for Asian Historical Records)