This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Yobot (talk | contribs) at 05:21, 8 December 2015 (Removed invisible unicode characters + other fixes, replaced: → (2) using AWB (11754)). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 05:21, 8 December 2015 by Yobot (talk | contribs) (Removed invisible unicode characters + other fixes, replaced: → (2) using AWB (11754))(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)| This article relies excessively on references to primary sources. Please improve this article by adding secondary or tertiary sources. Find sources: "Sex differences in intelligence" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (July 2014) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

| Part of a series on |

| Sex differences in humans |

|---|

|

| Biology |

| Medicine and health |

| Neuroscience and psychology |

| Sociology and society |

Differences in intelligence have long been a topic of debate among researchers and scholars. With the advent of the concept of g or general intelligence some form of empiricism was allowed, but results are often inconsistent with studies showing either no differences or advantages for both sexes, with many showing a slight advantage for males. One study did find some advantage for women in later life, while another found that male advantages on some cognitive tests are minimized when controlling for socioeconomic factors. The differences in average IQ between men and women are small in magnitude and inconsistent in direction. Some studies have concluded that there is larger variability in male scores compared to female scores, which results in more males than females in the top and bottom of the IQ distribution. This remains a controversial claim.

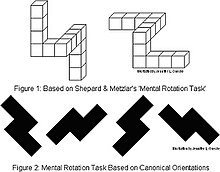

There are however differences in the capacity of males and females in performing certain tasks, such as rotation of object in space, often categorized as spatial ability.

Historical perspectives

Prior to the 20th century, it was a commonly held view that men were intellectually superior to women. Thomas Gisborne argued (1801) that women were naturally suited to domestic work and not spheres suited to men such as politics, science, or business. He argued that this was because women did not possess the same level of rational thinking that men did and had naturally superior abilities in skills related to family support.

In 1875, Herbert Spencer argued that women were incapable of abstract thought and could not understand issues of justice, and only had the ability to understand issues of care. In 1925, Sigmund Freud also concluded that women were less morally developed in the concept of justice, and, unlike men, were more influenced by feeling than rational thought. Early brain studies comparing mass and volumes between the sexes concluded that women were intellectually inferior because they had smaller and lighter brains (in reality, both genders are equally encephalized, having the same brain-to-body mass ratio, but women have a smaller mean body mass). Many believed that the size difference caused women to be excitable, emotional, sensitive, and therefore not suited for political participation.

In the nineteenth century, whether men and women had equal intelligence was seen by many as a prerequisite for the granting of suffrage. Leta Hollingworth argues that women were not permitted to realize their full potential, as they were confined to the roles of child-rearing and housekeeping.

During the early twentieth century, the scientific consensus shifted to the view that gender plays no role in intelligence. In his 1916 study of children's IQs, psychologist Lewis Terman concluded that "the intelligence of girls, at least up to 14 years, does not differ materially from that of boys". He did, however, find "rather marked" differences on a minority of tests. For example, he found boys were "decidedly better" in arithmetical reasoning, while girls were "superior" at answering comprehension questions. He also proposed that discrimination, lack of opportunity, women's responsibilities in motherhood, or emotional factors may have accounted for the fact that few women had careers in intellectual fields.

Current research on general intelligence

According to the 1994 report "Intelligence: Knowns and Unknowns" by the American Psychological Association, "Most standard tests of intelligence have been constructed so that there are no overall score differences between females and males." Differences have been found, however, in specific areas such as mathematics and verbal measures.

When standardized IQ tests were first developed in the early 20th century, girls typically scored higher than boys until age 14, at which time the curve for girls dropped below that for boys. As testing methodology was revised, efforts were made to equalize gender performance.

The mean IQ scores between men and women vary little. The variability of male scores is greater than that of females, however, resulting in more males than females in the top and bottom of the IQ distribution.

Several meta-studies by Richard Lynn between 1994 and 2005 found mean IQ of men exceeding that of women by a range of 3–5 points. Lynn's findings were debated in a series of articles for Nature. Jackson and Rushton found males aged 17–18 years had average of 3.63 IQ points in excess of their female equivalents. A 2005 study by Helmuth Nyborg found an average advantage for males of 3.8 IQ points. One study concluded that after controlling for sociodemographic and health variables, "gender differences tended to disappear on tests for which there was a male advantage and to magnify on tests for which there was a female advantage." A study from 2007 found a 2-4 IQ point advantage for females in later life. One study investigated the differences in IQ between the sexes in relation to age, finding that girls do better at younger ages but that their performance declines relative to boys with age. Colom et al. (2002) found 3.16 higher IQ points for males but no difference on the general intelligence factor (g) and therefore explained the differences as due to non-g factors such as specific group factors and test specificity. A study conducted by Jim Flynn and Lilia Rossi-Case (2011) found that men and women achieved roughly equal IQ scores on Raven's Progressive Matrices after reviewing recent standardization samples in five modernized nations. Irwing (2012) found a 3 point IQ advantage for males in g from subjects aged 16–89 in the United States.

Differences in brain physiology between sexes do not necessarily relate to differences in intellect. Haier et al. found in a 2004 study that: "Men and women apparently achieve similar IQ results with different brain regions, suggesting that there is no singular underlying neuroanatomical structure to general intelligence and that different types of brain designs may manifest equivalent intellectual performance. For men, the gray matter volume in the frontal and parietal lobes correlates with IQ; for women, the gray matter volume in the frontal lobe and Broca's area (which is used in language processing) correlates with IQ.

Some studies have identified the degree of IQ variance as a difference between males and females. Males tend to show greater variability on many traits including tests of cognitive abilities, though this may differ between countries. A 2005 study by Ian Deary, Paul Irwing, Geoff Der, and Timothy Bates, focusing on the ASVAB showed a significantly higher variance in male scores, resulting in more than twice as many men as women scoring in the top 2%. The study also found a very small (d' ≈ 0.07, less than 7%, of a standard deviation) average male advantage in g. A 2006 study by Rosalind Arden and Robert Plomin focused on children aged 2, 3, 4, 7, 9 and 10 and stated that there was greater variance "among boys at every age except age two despite the girls’ mean advantage from ages two to seven. Girls are significantly over-represented, as measured by chi-square tests, at the high tail and boys at the low tail at ages 2, 3 and 4. By age 10 the boys have a higher mean, greater variance and are over-represented in the high tail."

John Archer and Barbara LloydThe variability hypothesis still evokes controversy, but recent data and analyses may bring some closure to the debate Data from a number of representative mental test surveys, involving samples drawn from the national population, have become available in the past twenty years in the USA. These have finally provided consistent results. Both Feingold (1992b) and Hedges and Nowell (1995) have reported that, despite average sex differences being small and relatively stable over time, test score variances of males were generally larger than those of females. Feingold found that males were more variable than females on tests of quantitative reasoning, spatial visualisation, spelling, and general knowledge. Hedges and Nowell go one step further and demonstrate that, with the exception of performance on tests of reading comprehension, perceptual speed, and associative memory, more males than females were observed among high-scoring individuals.

Another study on intelligence came up with similar findings. Young adolescents were asked to volunteer in this study and completed various assessments including ones looking at language, math, and sciences skills as well as the Toulous-Pieron test of attention and the Dominoes test. While one sample of children completed these assessments, another sample completed these plus another handful. The test results from both samples show a null sex difference in general intelligence in young adolescents. Researchers concluded that since g does not differ through academic and cognitive abilities in young adolescents, male or female, and that some other factor must be responsible for the variance between the sexes.

A 2008 study with a sample of 6818 adults and children from 6 to 59 found different results on the WJ III IQ test. The study showed a moderate mean difference favouring females on the latent processing speed (Gs)factor, and a small difference favoring males on the latent comprehension–knowledge (Gc) factor.Males also showed an advantage on latent visual–spatial reasoning (Gv)and latent quantitative reasoning (RQ) factor. The latent overall g factor was inconsistent in children, small but not significant differences favoring females during adolescence, and consistent differences favoring females during adulthood. There were no gender differences in latent long-term retrieval (Glr),short-term memory (Gsm), auditory proces-sing (Ga) and fluid reasoning (Gf) variables. The finding of the study is a matter of fact inconsistent with Lynn's developmental theory that by 16 males should have about 4 points IQ difference over females. Professor and lead researcher Timothy Keith suggests past research like Lynn's had instead used composite scores to calculate g which may be prone to error, and so further research on latent factors are needed in the future.

It was believed at one point that Gf, or fluid intelligence, can be used to systematically detect sex differences in general intelligence if there are any. The PMA Inductive Reasoning Test, Cattell’s Culture-Fair Intelligence Test, and the Advanced Progressive Matrices were used to test a group of about 4000 high school graduates. Through the results of these tests, researchers discovered that females perform better in the PMA Inductive Reasoning Test and males perform better in the Advanced Progressive Matrices assessment. There was no sex difference noted from the results of the Culture-Fair Test. Sex difference in fluid intelligence was proven to not exist in this study.

In a 2012 review by 6 prominent researchers, they addressed Arthur Jensen's 1998 studies on sex differences in intelligence in tests that were “loaded heavily on g” but were not set-up to eliminate sex differences(since most tests are set-up to eliminate unnecessary differences). They summarized that his conclusions were as he quoted "No evidence was found for sex differences in the mean level of g or in the variability of g.Males, on average,excel on some factors; females on others”. Jensen’s results that no overall sex differences existed for g has been strengthened by researchers who assessed this issue with a battery of 42 mental ability tests and found no overall sex difference.

Although most of the tests showed no difference, there were some that did. For example, they found female performed better on verbal abilities while males performed better on visuospatial abilities. For verbal fluency, females have been specifically found to perform better in vocabulary, reading comprehension, speech production and essay writing. Males have been specifically found to perform better on spatial visualization, spatial perception, and mental rotation. Researchers had then recommended that general models such as fluid and crystallized intelligence be divided into verbal, perceptual and visuospatial domains of g, because when this model is applied then females excel at verbal and perceptual tasks while males on visuospatial tasks. Thus evening out the sex differences on IQ tests.

While research has shown that males and females do indeed each excel in different abilities, math and science might be an exception to this.

Mathematics performance

Large, representative studies of US students show that no sex differences in mathematics performance exist before secondary school. During and after secondary school, historic sex differences in mathematics enrollment account for nearly all of the sex differences in mathematics performance. However, a performance difference in mathematics on the SAT exists favoring males, though differences in mathematics course performance measures favor females. In 1983, Benbow concluded that the study showed a large sex difference by age 13 and that it was especially pronounced at the high end of the distribution. However, Gallagher and Kaufman criticized Benbow's and other reports finding males overrepresented in the highest percentages as not ensuring representative sampling.

In a 2008 study paid for by the National Science Foundation in the United States, researchers found that "girls perform as well as boys on standardized math tests. Although 20 years ago, high school boys performed better than girls in math, the researchers found that is no longer the case. The reason, they said, is simple: Girls used to take fewer advanced math courses than boys, but now they are taking just as many." However, the study indicated that, while on average boys and girls performed similarly, boys were overrepresented among the very best performers as well as among the very worst. A 2011 meta-analysis with 242 studies from 1990 to 2007 involving 1,286,350 people found no overall sex difference of performance in Mathematics. The meta-analysis also found that although there were no overall differences, a small sex difference that favored males in complex problem solving is still present in high school.

Kiefer and Sekaquaptewa proposed that a source of some women's underperformance and lowered perseverance in mathematical fields is these women's underlying "implicit" sex-based stereotypes regarding mathematical ability and association, as well as their identification with their gender. Some psychologists believe that many historical and current sex differences in mathematics performance may be related to boy's higher likelihood of receiving math encouragement than girls. Parents were, and sometimes still are, more likely to consider a son's mathematical achievement as being a natural skill while a daughter's mathematical achievement is more likely to be seen as something she studied hard for. This difference in attitude may contribute to girls and women being discouraged from further involvement in mathematics-related subjects and careers. Stereotype threat has been shown to affect performance and confidence in mathematics of both males and females. However, a review of stereotype threat literature found most studies couldn't be replicated or suffered methodological problems and concluded "that although stereotype threat may affect some women, the existing state of knowledge does not support the current level of enthusiasm for this as a mechanism underlying the gender gap in mathematics."

Two cross-country comparisons have found great variation in the gender differences regarding the degree of variance in mathematical ability. In most nations males have greater variance. In a few females have greater variance. Hyde and Mertz argue that boys and girls differ in the variance of their ability due to sociocultural factors.

Spatial ability

Some studies investigating the spatial abilities of men and women have found no significant differences, though metastudies show a male advantage in mental rotation and assessing horizontality and verticality, and a female advantage in spatial memory.

A proposed hypothesis is that men and women evolved different mental abilities to adapt to their different roles in society. This explanation suggests that men may have evolved greater spatial abilities as a result of certain behaviors, such as navigating during a hunt. Similarly, this hypothesis suggests that women may have evolved to devote more mental resources to remembering locations of food sources in relation to objects and other features in order to gather food.

A number of studies have shown that women tend to rely more on visual information than men in a number of spatial tasks related to perceived orientation. However, 'visual dependence' has been found to be task specific and not a general characteristic of spatial processing that differs between the sexes. Here an alternative hypothesis suggests that heightened visual dependence in females does not generalize to all aspects of spatial processing but is probably attributable to task-specific differences in how male and females brains process multisensory spatial information.

Results from studies conducted in the physical environment are not conclusive about sex differences, with various studies on the same task showing no differences. For example, there are studies that show no difference in 'wayfinding'. One study found men more likely to report having a good sense of direction and are more confident about finding their way in a new environment, but evidence does not support men having better map reading skills. Women have been found to use landmarks more often when giving directions and when describing routes. Additionally, a study concludes that women are better at recalling where objects are located in a physical environment. Women show greater proficiency and reliance on distinctive landmarks for navigation while males rely on an overall mental map.

Performance in mental rotation and similar spatial tasks is affected by gender expectations. For example, studies show that being told before the test that men typically perform better, or that the task is linked with jobs like aviation engineering typically associated with men versus jobs like fashion design typically associated with women, will negatively affect female performance on spatial rotation and positively influence it when subjects are told the opposite. Experiences such as playing video games also increase a person's mental rotation ability. A study from the University of Toronto showed that differences in ability get reduced after playing video games requiring complex mental rotation. The experiment showed that playing such games creates larger gains in spatial cognition in females than males.

The possibility of testosterone and other androgens as a cause of sex differences in psychology has been a subject of study. Adult women who were exposed to unusually high levels of androgens in the womb due to congenital adrenal hyperplasia score significantly higher on tests of spatial ability. Many studies find positive correlations between testosterone levels in healthy males and measures of spatial ability. However, the relationship is complex.

A study was done to compare the relationship between mental rotation ability and gender difference specifically with the SAT-Math. Cognitive gender differences are apparent and findings of a male advantage in certain mathematical domains have been demonstrated cross-culturally. These gender differences found are largely in geometry and word problems and tend to be in countries with the highest achieving students and with the largest gender gap in experience. Smaller differences were noted in countries with lower achieving students in mathematics which includes the United States. Moore and Smith state that within the United States, poorly educated female students outperform their male peers, but as the level of education increases, the male advantage in mathematics emerges.

Spatial ability may be responsible in part for facilitating gender differences in math aptitude. Casey et al. (1995) looked at the relationship of mental rotation ability and the SAT-M among four samples. The four samples were: (1) undergraduates at two liberal arts colleges in the Northeast that were tested on their mental rotation ability in groups of 10-20, (2) a group of mathematically talented preadolescents participating in a summer math and science training in the Midwest which included seventh to ninth graders who were either recruited from a national talent search program or statewide teacher selection program, (3) a high ability group of college bound students who were enrolled in a middle-income suburban high school in the Northeast and elected to take the SAT, and (4) a low ability group of college bound students who were enrolled in a middle-income suburban high school in the Northeast and elected to take the SAT. The data used were SAT math and verbal scores and mental rotation scores. Mental rotation was assessed using the Vandenberg Test of Mental Rotation. Students were asked to match two out of four choices to a standard figure.

The study found that that when mental rotation is used as a predictor of Math aptitude for female students, the correlations between mental rotation and SAT-Math scores ranged from 0.35 to 0.38 whereas males showed no consistent pattern. Male correlations ranged from -0.03 to 0.54. However, an interesting finding was that in the three high ability samples, there was a significant gender difference in SAT-Math scores alone. This difference favored males. In the three high ability samples, males scored higher than females in mental rotation ability. Interesting enough, for the verbal aptitude test on SAT, there was a significant difference in verbal ability for the low ability college bound sample favoring girls.

Dyslexia

Dyslexia is a learning disability that impairs a person’s fluency or comprehension accuracy in being able to read. The cause of this disability is associated with abnormal brain anatomy and function. Gray matter deficits have been demonstrated in dyslexics using structural magnetic resonance imaging. This deficit has been found in specific regions within the left hemisphere involved in language.

There is higher prevalence of dyslexia in males than in females. However, different abnormalities are found in female brains as opposed to male brains. In a study that examined gray matter volume in dyslexic females, it was found that there was less gray matter volume in the right precuneus and paracentral lobule/medial frontal gyrus. In males, there was less gray matter volume in the left inferior parietal cortex. This study shows that dyslexia in females does not involve the left hemisphere regions involved in language as it does in males. Instead, it affects the sensory and motor cortices such as the motor and premotor cortex and primary visual cortex.

References

- ^ Lynn, Richard (1999). "Sex differences in intelligence and brain size: A developmental theory". Intelligence. 27: 1–12. doi:10.1016/S0160-2896(99)00009-4.

- ^ Irwing, Paul; Lynn, Richard (2005). "Sex differences in means and variability on the progressive matrices in university students: A meta-analysis". British Journal of Psychology. 96 (4): 505–24. doi:10.1348/000712605X53542. PMID 16248939.

- ^ Lynn, Richard (1994). "Sex differences in intelligence and brain size: A paradox resolved". Personality and Individual Differences. 17 (2): 257–71. doi:10.1016/0191-8869(94)90030-2.

- ^ Blinkhorn, Steve (2005). "Intelligence: A gender bender". Nature. 438 (7064): 31–2. Bibcode:2005Natur.438...31B. doi:10.1038/438031a. PMID 16267535.

- ^ Irwing, Paul; Lynn, Richard (2006). "Intelligence: Is there a sex difference in IQ scores?". Nature. 442 (7098): E1, discussion E1–2. Bibcode:2006Natur.442E...1I. doi:10.1038/nature04966. PMID 16823409.

- ^ Jackson, Douglas N.; Rushton, J. Philippe (2006). "Males have greater g: Sex differences in general mental ability from 100,000 17- to 18-year-olds on the Scholastic Assessment Test". Intelligence. 34 (5): 479–486. doi:10.1016/j.intell.2006.03.005.

- ^ Nyborg, Helmuth (2005). "Sex-related differences in general intelligence g, brain size, and social status". Personality and Individual Differences. 39 (3): 497–509. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2004.12.011.

- Keith, Timothy Z.; Reynolds, Matthew R.; Patel, Puja G.; Ridley, Kristen P. (2008). "Sex differences in latent cognitive abilities ages 6 to 59: Evidence from the Woodcock–Johnson III tests of cognitive abilities". Intelligence. 36 (6): 502–25. doi:10.1016/j.intell.2007.11.001.

- ^ Jorm, Anthony F.; Anstey, Kaarin J.; Christensen, Helen; Rodgers, Bryan (2004). "Gender differences in cognitive abilities: The mediating role of health state and health habits". Intelligence. 32: 7–23. doi:10.1016/j.intell.2003.08.001.

- ^ Neisser, Ulric; Boodoo, Gwyneth; Bouchard, Thomas J., Jr.; Boykin, A. Wade; Brody, Nathan; Ceci, Stephen J.; Halpern, Diane F.; Loehlin, John C.; Perloff, Robert (1996). "Intelligence: Knowns and Unknowns". American Psychologist. 51 (2): 77–101. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.51.2.77.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Baumeister, Roy F (2001). Social psychology and human sexuality: essential readings. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-1-84169-019-3.

- ^ Baumeister, Roy F. (2010). Is there anything good about men?: how cuflourish by exploiting men. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-537410-0.

- ^ Hedges, L.; Nowell, A (1995). "Sex differences in mental test scores, variability, and numbers of high-scoring individuals". Science. 269 (5220): 41–5. Bibcode:1995Sci...269...41H. doi:10.1126/science.7604277. PMID 7604277.

- ^ Colom, R; García, LF; Juan-Espinosa, M; Abad, FJ (2002). "Null sex differences in general intelligence: Evidence from the WAIS-III". The Spanish journal of psychology. 5 (1): 29–35. doi:10.1017/s1138741600005801. PMID 12025362.

- ^ Deary, Ian J.; Irwing, Paul; Der, Geoff; Bates, Timothy C. (2007). "Brother–sister differences in the g factor in intelligence: Analysis of full, opposite-sex siblings from the NLSY1979". Intelligence. 35 (5): 451–6. doi:10.1016/j.intell.2006.09.003.

- ^ Wai, Jonathan; Cacchio, Megan; Putallaz, Martha; Makel, Matthew C. (2010). "Sex differences in the right tail of cognitive abilities: A 30year examination". Intelligence. 38 (4): 412–423. doi:10.1016/j.intell.2010.04.006. ISSN 0160-2896.

- Spelke, E. (2005). "Sex differences in intrinsic aptitude for mathematics and science?: A critical review". American Psychologist: 950–958. PMID 16366817.

- Lips, Hilary M. (1997). Sex & Gender: An Introduction (3rd ed.). Mountain View, Calif.: Mayfield. p. 40. ISBN 1559346302.

- Denmark, Florence L.; Paludi, Michele A. (2008). Psychology of Women: A Handbook of Issues and Theories (2nd ed.). Westport, Conn.: Praeger. pp. 7–11. ISBN 0275991628.

- Thomas Gisborne, An enquiry into the duties of the female sex, Printed by A. Strahan for T. Cadell jun. and W. Davies, 1801

- ^ Judith Worell, Encyclopedia of women and gender: sex similarities and differences and the impact of society on gender, Volume 1, Elsevier, 2001, ISBN 0-12-227246-3, ISBN 978-0-12-227246-2

- ^ Fine, Cordelia (2010). Delusions of Gender: How Our Minds, Society, and Neurosexism Create Difference. W. W. Norton. ISBN 0-393-06838-2.

- ^ Margarete Grandner, Austrian women in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries: cross-disciplinary perspectives, Berghahn Books, 1996, ISBN 1-57181-045-5, ISBN 978-1-57181-045-8

- Burt, C. L.; Moore, R. C. (1912). "The mental differences between the sexes". Journal of Experimental Pedagogy. 1 (273–284): 355–388.

- ^ Terman, Lewis M. (1916). The measurement of intelligence: an explanation of and a complete guide for the use of the Stanford revision and extension of the Binet-Simon intelligence scale. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. pp. 68–72. OCLC 186102.

- ^ Rider, Elizabeth A. (2000). Our Voices: Psychology of Women. Belmont, California: Wadsworth. p. 202. ISBN 0-534-34681-2.

- Archer, John, Barbara Bloom Lloyd, Sex and Gender, Cambridge University Press, 2002, ISBN 0-521-63533-0, ISBN 978-0-521-63533-2

- Sternberg, Robert J., Handbook of Intelligence, Cambridge University Press, 2000, ISBN 0-521-59648-3

- Lynn, Richard; Irwing, Paul (2004). "Sex differences on the progressive matrices: A meta-analysis". Intelligence. 32 (5): 481–498. doi:10.1016/j.intell.2004.06.008.

- Keith, Timothy Z.; Reynolds, Matthew R.; Patel, Puja G.; Ridley, Kristen P. (2008). "Sex differences in latent cognitive abilities ages 6 to 59: Evidence from the Woodcock–Johnson III tests of cognitive abilities". Intelligence. 36 (6): 502–25. doi:10.1016/j.intell.2007.11.001.

- Colom, Roberto; Lynn, Richard (2004). "Testing the developmental theory of sex differences in intelligence on 12–18 year olds". Personality and Individual Differences. 36: 75–82. doi:10.1016/S0191-8869(03)00053-9.

- Flynn, Jim; Rossi-Casé, Lilia (2011). "Modern women match men on Raven's Progressive Matrices". Personality and Individual Differences. 50 (6): 799–803. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2010.12.035.

- Irwing, Paul (2012). "Sex differences in g: An analysis of the US standardization sample of the WAIS-III". Personality and Individual Differences. 53 (2): 126–31. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2011.05.001.

- Haier, Richard J.; Jung, Rex E.; Yeo, Ronald A.; Head, Kevin; Alkire, Michael T. (2005). "The neuroanatomy of general intelligence: Sex matters". NeuroImage. 25 (1): 320–7. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.11.019. PMID 15734366.

- Cosgrove, Kelly P.; Mazure, Carolyn M.; Staley, Julie K. (2007). "Evolving Knowledge of Sex Differences in Brain Structure, Function, and Chemistry". Biological Psychiatry. 62 (8): 847–55. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.03.001. PMC 2711771. PMID 17544382.

- Lehrke, R. (1997). Sex linkage of intelligence: The X-Factor. NY: Praeger.

- Lubinski, D.; Benbow, C. P. (2006). "Study of Mathematically Precocious Youth After 35 Years: Uncovering Antecedents for the Development of Math-Science Expertise". Perspectives on Psychological Science. 1 (4): 316–45. doi:10.1111/j.1745-6916.2006.00019.x. JSTOR 40212176.

- ^ Hyde, J. S.; Mertz, J. E. (2009). "Gender, culture, and mathematics performance". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 106 (22): 8801–7. Bibcode:2009PNAS..106.8801H. doi:10.1073/pnas.0901265106. PMC 2689999. PMID 19487665.

- Hedges, Larry V.; Nowell, Amy (1995). "Sex Differences in Mental Test Scores, Variability, and Numbers of High-Scoring Individuals". Science. 269 (5220): 41–5. Bibcode:1995Sci...269...41H. doi:10.1126/science.7604277. PMID 7604277.

- Ali, MS; Suliman, MI; Kareem, A; Iqbal, M (2009). "Comparison of gender performance on an intelligence test among medical students". Journal of Ayub Medical College, Abbottabad. 21 (3): 163–5. PMID 20929039.

- Arden, Rosalind; Plomin, Robert (2006). "Sex differences in variance of intelligence across childhood". Personality and Individual Differences. 41: 39–48. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2005.11.027.

- Archer, John; Lloyd, Barbara (2002). Sex and Gender (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 186–8.

- ^ Aluja-Fabregat, Anton; Colom, Roberto; Abad, Francisco; Juan-Espinosa, Manuel (2000). "Sex differences in general intelligence defined as g among young adolescents". Personality and Individual Differences. 28 (4): 813–20. doi:10.1016/S0191-8869(99)00142-7.

- Keith, Timothy Z.; Reynolds, Matthew R.; Patel, Puja G.; Ridley, Kristen P. "Sex differences in latent cognitive abilities ages 6 to 59: Evidence from the Woodcock–Johnson III tests of cognitive abilities". Intelligence. 36 (6): 502–525. doi:10.1016/j.intell.2007.11.001.

- ^ Colom, Roberto; Garcı́a-López, Oscar (2002). "Sex differences in fluid intelligence among high school graduates". Personality and Individual Differences. 32 (3): 445–451. doi:10.1016/S0191-8869(01)00040-X.

- ^ Nisbet, Richard E (2012). "Intelligence New Findings and Theoretical Developments" (PDF). Intelligence. doi:10.1037/a0026699.

- ^ (us), National Academy of Sciences; (us), National Academy of Engineering; Engineering, and Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Maximizing the Potential of Women in Academic Science and (2006-01-01). "Women in Science and Mathematics".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Halpern, Diane F.; Benbow, Camilla P.; Geary, David C.; Gur, Ruben C.; Hyde, Janet Shibley; Gernsbacher, Morton Ann (2007). "The Science of Sex Differences in Science and Mathematics". Psychological Science in the Public Interest. 8: 1–51. doi:10.1111/j.1529-1006.2007.00032.x.

- ^ Ann M. Gallagher, James C. Kaufman, Gender differences in mathematics: an integrative psychological approach, Cambridge University Press, 2005, ISBN 0-521-82605-5, ISBN 978-0-521-82605-1

- Benbow, C.; Stanley, J. (1983). "Sex differences in mathematical reasoning ability: More facts". Science. 222 (4627): 1029–31. doi:10.1126/science.6648516. PMID 6648516.

- Lewin, Tamar (July 25, 2008)."Math Scores Show No Gap for Girls, Study Finds", The New York Times.

- Hyde, J. S.; Lindberg, S. M.; Linn, M. C.; Ellis, A. B.; Williams, C. C. (2008). "DIVERSITY: Gender Similarities Characterize Math Performance". Science. 321 (5888): 494–5. doi:10.1126/science.1160364. PMID 18653867.

- Winstein, Keith J. (July 25, 2008). "Boys' Math Scores Hit Highs and Lows", The Wall Street Journal (New York).

- Benbow, C. P.; Lubinski, D.; Shea, D. L.; Eftekhari-Sanjani, H. (2000). "Sex Differences in Mathematical Reasoning Ability at Age 13: Their Status 20 Years Later". Psychological Science. 11 (6): 474–80. doi:10.1111/1467-9280.00291. PMID 11202492.

- Lindberg, Sara M.; Hyde, Janet Shibley; Petersen, Jennifer L.; Linn, Marcia C. (2010-11-01). "New Trends in Gender and Mathematics Performance: A Meta-Analysis". Psychological bulletin. 136 (6): 1123–1135. doi:10.1037/a0021276. ISSN 0033-2909. PMC 3057475. PMID 21038941.

- Implicit Stereotypes and Gender Identification May Affect Female Math Performance. Science Daily (Jan 24, 2007).

- Wood, Samual; Wood, Ellen; Boyd Denise (2004). "World of Psychology, The (Fifth Edition)" , Allyn & Bacon ISBN 0-205-36137-4

- Stoet, Gijsbert; Geary, David C. (2012). "Can stereotype threat explain the gender gap in mathematics performance and achievement?". Review of General Psychology. 16: 93–102. doi:10.1037/a0026617.

- Penner, Andrew M. (2008). "Gender Differences in Extreme Mathematical Achievement: An International Perspective on Biological and Social Factors". American Journal of Sociology. 114: S138. doi:10.1086/589252.

- Machin, S.; Pekkarinen, T. (2008). "ASSESSMENT: Global Sex Differences in Test Score Variability". Science. 322 (5906): 1331–2. doi:10.1126/science.1162573. PMID 19039123.

- Corley, DeFries, Kuse, Vandenberg. 1980. Familial Resemblance for the Identical Blocks Test of Spatial Ability: No Evidence of X Linkage. Behavior Genetics.

- Julia A. Sherman. 1978. Sex-Related Cognitive Differences: An Essay on Theory and Evidence Springfield.

- Chrisler, Joan C; Donald R. McCreary. Handbook of Gender Research in Psychology. Springer, 2010. ISBN 9781441914644.

- Halpern, Diane F., Sex differences in cognitive abilities, Psychology Press, 2000, ISBN 0-8058-2792-7, ISBN 978-0-8058-2792-7

- Ellis, Lee, Sex differences: summarizing more than a century of scientific research, CRC Press, 2008, ISBN 0-8058-5959-4, ISBN 978-0-8058-5959-1

- Eals, Marion, and Irwin Silverman. 1992. Sex differences in spatial abilities: evolutionary theory and data. In The Adapted Mind: Evolutionary Psychology and the Generation of Culture, edited by J. H. Barkow. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Jones, C. M; Healy, S. D (2006). "Differences in cue use and spatial memory in men and women". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 273 (1598): 2241–2247. doi:10.1098/rspb.2006.3572.

- Geary, David C. (1998). Male, female: The evolution of human sex differences. American Psychological Association. ISBN 1-55798-527-8.

- New, J.; Krasnow, M. M; Truxaw, D.; Gaulin, S. J.C (2007). "Spatial adaptations for plant foraging: Women excel and calories count". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 274 (1626): 2679–2684. doi:10.1098/rspb.2007.0826.

- Witkin, H. A., Lewis, H. B., Hertzman, M., Machover, K., Meissner, P. B. & Wapner, S. (1954) Personality Through Perception. An Experimental and Clinical Study. Harper, New York.

- Linn, Marcia C.; Petersen, Anne C. (1985). "Emergence and Characterization of Sex Differences in Spatial Ability: A Meta-Analysis". Child Development. 56 (6): 1479–98. doi:10.2307/1130467. JSTOR 1130467. PMID 4075870.

- Barnett-Cowan, M.; Dyde, R. T.; Thompson, C.; Harris, L. R. (2010). "Multisensory determinants of orientation perception: Task-specific sex differences". European Journal of Neuroscience. 31 (10): 1899–907. doi:10.1111/j.1460-9568.2010.07199.x. PMID 20584195.

- ^ Devlin, Ann Sloan, Mind and maze: spatial cognition and environmental behavior, Praeger, 2001, ISBN 0-275-96784-0, ISBN 978-0-275-96784-0

- ^ Montello, Daniel R.; Lovelace, Kristin L.; Golledge, Reginald G.; Self, Carole M. (1999). "Sex-Related Differences and Similarities in Geographic and Environmental Spatial Abilities". Annals of the Association of American Geographers. 89 (3): 515–534. doi:10.1111/0004-5608.00160.

- Miller, Leon K.; Santoni, Viana (1986). "Sex differences in spatial abilities: Strategic and experiential correlates". Acta Psychologica. 62 (3): 225–35. doi:10.1016/0001-6918(86)90089-2. PMID 3766198.

- Kimura, Doreen (May 13, 2002). "Sex Differences in the Brain: Men and women display patterns of behavioral and cognitive differences that reflect varying hormonal influences on brain development", Scientific American.

- National Geographic - My Brilliant Brain "Make Me a Genius" http://video.google.com/videoplay?docid=-6378985927858479238#

- Paula J. Caplan, Gender differences in human cognition, Oxford University Press US, 1997, ISBN 0-19-511291-1, ISBN 978-0-19-511291-7

- Newcombe, N. S. (2007). Taking Science Seriously: Straight thinking about spatial sex differences. In S. Ceci & W. Williams (eds.), Why aren't more women in science? Top researchers debate the evidence (pp. 69-77). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- "SPATIAL COGNITION AND GENDER Instructional and Stimulus Influences on Mental Image Rotation Performance". Psychology of Women Quarterly. 18: 413–425. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.1994.tb00464.x.

- McGlone, Matthew S.; Aronson, Joshua (2006). "Stereotype threat, identity salience, and spatial reasoning". Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 27 (5): 486–493. doi:10.1016/j.appdev.2006.06.003.

- Hausmann, Markus; Schoofs, Daniela; Rosenthal, Harriet E.S.; Jordan, Kirsten (2009). "Interactive effects of sex hormones and gender stereotypes on cognitive sex differences—A psychobiosocial approach". Psychoneuroendocrinology. 34 (3): 389–401. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2008.09.019. PMID 18992993.

- Cherney, Isabelle D. (2008). "Mom, Let Me Play More Computer Games: They Improve My Mental Rotation Skills". Sex Roles. 59 (11–12): 776–86. doi:10.1007/s11199-008-9498-z.

- Feng, J.; Spence, I.; Pratt, J. (2007). "Playing an Action Video Game Reduces Gender Differences in Spatial Cognition". Psychological Science. 18 (10): 850–5. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01990.x. PMID 17894600.

- Resnick, Susan M.; Berenbaum, Sheri A.; Gottesman, Irving I.; Bouchard, Thomas J. (1986). "Early hormonal influences on cognitive functioning in congenital adrenal hyperplasia". Developmental Psychology. 22 (2): 191–198. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.22.2.191.

- Janowsky, Jeri S.; Oviatt, Shelia K.; Orwoll, Eric S. (1994). "Testosterone influences spatial cognition in older men". Behavioral Neuroscience. 108 (2): 325–32. doi:10.1037/0735-7044.108.2.325. PMID 8037876.

- Gouchie, C; Kimura, D (1991). "The relationship between testosterone levels and cognitive ability patterns". Psychoneuroendocrinology. 16 (4): 323–34. doi:10.1016/0306-4530(91)90018-O. PMID 1745699.

- Nyborg, H. (1984). "Sex Differences in the Brain - the Relation Between Structure and Function". Progress in brain research. Progress in Brain Research. 61: 491–508. doi:10.1016/S0079-6123(08)64456-8. ISBN 978-0-444-80532-4. PMID 6396713.

{{cite journal}}:|chapter=ignored (help) - ^ Casey, M. Beth; Nuttall, Ronald; Pezaris, Elizabeth; Benbow, Camilla Persson (1995). "The influence of spatial ability on gender differences in mathematics college entrance test scores across diverse samples". Developmental Psychology. 31 (4): 697–705. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.31.4.697.

- "Dyslexia Information Page".

- Sun, Ying-Fang; Lee, Jeun-Shenn; Kirby, Ralph (2010). "Brain Imaging Findings in Dyslexia". Pediatrics & Neonatology. 51 (2): 89–96. doi:10.1016/S1875-9572(10)60017-4.

- ^ Evans, Tanya M.; Flowers, D. Lynn; Napoliello, Eileen M.; Eden, Guinevere F. (2013). "Sex-specific gray matter volume differences in females with developmental dyslexia". Brain Structure and Function. 219: 1041–1054. doi:10.1007/s00429-013-0552-4.

| Sex differences in humans | ||

|---|---|---|

| Biology |  | |

| Medicine and Health | ||

| Neuroscience and Psychology | ||

| Sociology | ||