This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Doc James (talk | contribs) at 19:04, 13 April 2016 (Reverted to revision 706977467 by Charlesdrakew (talk): Removed small primary source. (TW)). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 19:04, 13 April 2016 by Doc James (talk | contribs) (Reverted to revision 706977467 by Charlesdrakew (talk): Removed small primary source. (TW))(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) Medical condition| Skin cancer | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Oncology and dermatology |

Skin cancers are cancers that arise from the skin. They are due to the development of abnormal cells that have the ability to invade or spread to other parts of the body. There are three main types: basal-cell cancer (BCC), squamous-cell cancer (SCC) and melanoma. The first two together along with a number of less common skin cancers are known as nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC). Basal-cell cancer grows slowly and can damage the tissue around it but is unlikely to spread to distant areas or result in death. It often appears as a painless raised area of skin, that may be shiny with small blood vessel running over it or may present as a raised area with an ulcer. Squamous-cell cancer is more likely to spread. It usually presents as a hard lump with a scaly top but may also form an ulcer. Melanomas are the most aggressive. Signs include a mole that has changed in size, shape, color, has irregular edges, has more than one color, is itchy or bleeds.

Greater than 90% of cases are caused by exposure to ultraviolet radiation from the Sun. This exposure increases the risk of all three main types of skin cancer. Exposure has increased partly due to a thinner ozone layer. Tanning beds are becoming another common source of ultraviolet radiation. For melanomas and basal-cell cancers exposure during childhood is particularly harmful. For squamous-cell cancers total exposure, irrespective of when it occurs, is more important. Between 20% and 30% of melanomas develop from moles. People with light skin are at higher risk as are those with poor immune function such as from medications or HIV/AIDS. Diagnosis is by biopsy.

Decreasing exposure to ultraviolet radiation and the use of sunscreen appear to be effective methods of preventing melanoma and squamous-cell cancer. It is not clear if sunscreen affects the risk of basal-cell cancer. Nonmelanoma skin cancer is usually curable. Treatment is generally by surgical removal but may less commonly involve radiation therapy or topical medications such as fluorouracil. Treatment of melanoma may involve some combination of surgery, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and targeted therapy. In those people whose disease has spread to other areas of their bodies, palliative care may be used to improve quality of life. Melanoma has one of the higher survival rates among cancers, with over 86% of people in the UK and more than 90% in the United States surviving more than 5 years.

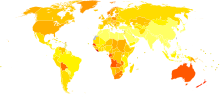

Skin cancer is the most common form of cancer, globally accounting for at least 40% of cases. It is especially common among people with light skin. The most common type is nonmelanoma skin cancer, which occurs in at least 2-3 million people per year. This is a rough estimate, however, as good statistics are not kept. Of nonmelanoma skin cancers, about 80% are basal-cell cancers and 20% squamous-cell cancers. Basal-cell and squamous-cell cancers rarely result in death. In the United States they were the cause of less than 0.1% of all cancer deaths. Globally in 2012 melanoma occurred in 232,000 people, and resulted in 55,000 deaths. Australia and New Zealand have the highest rates of melanoma in the world. The three main types of skin cancer have become more common in the last 20 to 40 years, especially in those areas which are mostly Caucasian.

Classification

There are three main types of skin cancer: basal-cell carcinoma (BCC), squamous-cell carcinoma (SCC) and malignant melanoma.

| Cancer | Description | Illustration |

|---|---|---|

| Basal-cell carcinoma | Note the pearly translucency to fleshy color, tiny blood vessels on the surface, and sometime ulceration which can be characteristics. The key term is translucency. |  |

| Squamous-cell carcinoma | Commonly presents as a red, crusted, or scaly patch or bump. Often a very rapid growing tumor. |  |

| Malignant melanoma | The common appearance is an asymmetrical area, with an irregular border, color variation, and often greater than 6 mm diameter. |  |

Basal-cell carcinomas are present on sun-exposed areas of the skin, especially the face. They rarely metastasize and rarely cause death. They are easily treated with surgery or radiation. Squamous-cell carcinomas (SCC) are common, but much less common than basal-cell cancers. They metastasize more frequently than BCCs. Even then, the metastasis rate is quite low, with the exception of SCC of the lip, ear, and in people who are immunosuppressed. Melanomas are the least frequent of the 3 common skin cancers. They frequently metastasize, and could potentially cause death once they spread.

Less common skin cancers include: dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, Merkel cell carcinoma, Kaposi's sarcoma, keratoacanthoma, spindle cell tumors, sebaceous carcinomas, microcystic adnexal carcinoma, Paget's disease of the breast, atypical fibroxanthoma, leiomyosarcoma, and angiosarcoma.

BCC and SCC often carry a UV-signature mutation indicating that these cancers are caused by UVB radiation via direct DNA damage. However malignant melanoma is predominantly caused by UVA radiation via indirect DNA damage. The indirect DNA damage is caused by free radicals and reactive oxygen species. Research indicates that the absorption of three sunscreen ingredients into the skin, combined with a 60-minute exposure to UV, leads to an increase of free radicals in the skin, if applied in too little quantities and too infrequently. However, the researchers add that newer creams often do not contain these specific compounds, and that the combination of other ingredients tends to retain the compounds on the surface of the skin. They also add the frequent re-application reduces the risk of radical formation.

Signs and symptoms

There are a variety of different skin cancer symptoms. These include changes in the skin that do not heal, ulcering in the skin, discolored skin, and changes in existing moles, such as jagged edges to the mole and enlargement of the mole.

Basal-cell carcinoma

Basal-cell carcinoma usually presents as a raised, smooth, pearly bump on the sun-exposed skin of the head, neck or shoulders. Sometimes small blood vessels (called telangiectasia) can be seen within the tumor. Crusting and bleeding in the center of the tumor frequently develops. It is often mistaken for a sore that does not heal. This form of skin cancer is the least deadly and with proper treatment can be completely eliminated, often without scarring.

Squamous-cell carcinoma

Squamous-cell carcinoma is commonly a red, scaling, thickened patch on sun-exposed skin. Some are firm hard nodules and dome shaped like keratoacanthomas. Ulceration and bleeding may occur. When SCC is not treated, it may develop into a large mass. Squamous-cell is the second most common skin cancer. It is dangerous, but not nearly as dangerous as a melanoma.

Melanoma

Most melanomas consist of various colours from shades of brown to black. A small number of melanomas are pink, red or fleshy in colour; these are called amelanotic melanomas and tend to be more aggressive. Warning signs of malignant melanoma include change in the size, shape, color or elevation of a mole. Other signs are the appearance of a new mole during adulthood or pain, itching, ulceration, redness around the site, or bleeding at the site. An often-used mnemonic is "ABCDE", where A is for "asymmetrical", B for "borders" (irregular: "Coast of Maine sign"), C for "color" (variegated), D for "diameter" (larger than 6 mm—the size of a pencil eraser) and E for "evolving."

Other

Merkel cell carcinomas are most often rapidly growing, non-tender red, purple or skin colored bumps that are not painful or itchy. They may be mistaken for a cyst or another type of cancer.

Causes

Ultraviolet radiation from sun exposure is the primary cause of skin cancer. Other factors that play a role include:

- Smoking tobacco

- HPV infections increase the risk of squamous-cell carcinoma.

- Some genetic syndromes including congenital melanocytic nevi syndrome which is characterized by the presence of nevi (birthmarks or moles) of varying size which are either present at birth, or appear within 6 months of birth. Nevi larger than 20 mm (3/4") in size are at higher risk for becoming cancerous.

- Chronic non-healing wounds. These are called Marjolin's ulcers based on their appearance, and can develop into squamous-cell carcinoma.

- Ionizing radiation, environmental carcinogens, artificial UV radiation (e.g. tanning beds), aging, and light skin color. It is believed that tanning beds are the cause of hundreds of thousands of basal and squamous-cell carcinomas. The World Health Organization now places people who use artificial tanning beds in its highest risk category for skin cancer.

- The use of many immunosuppressive medications increases the risk of skin cancer. Cyclosporin A, a calcineurin inhibitor for example increases the risk approximately 200 times, and azathioprine about 60 times.

Pathophysiology

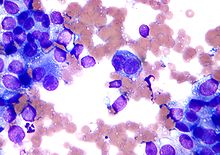

A malignant epithelial tumor that primarily originates in the epidermis, in squamous mucosa or in areas of squamous metaplasia is referred to as a squamous-cell carcinoma.

Macroscopically, the tumor is often elevated, fungating, or may be ulcerated with irregular borders. Microscopically, tumor cells destroy the basement membrane and form sheets or compact masses which invade the subjacent connective tissue (dermis). In well differentiated carcinomas, tumor cells are pleomorphic/atypical, but resembling normal keratinocytes from prickle layer (large, polygonal, with abundant eosinophilic (pink) cytoplasm and central nucleus).

Their disposal tends to be similar to that of normal epidermis: immature/basal cells at the periphery, becoming more mature to the centre of the tumor masses. Tumor cells transform into keratinized squamous cells and form round nodules with concentric, laminated layers, called "cell nests" or "epithelial/keratinous pearls". The surrounding stroma is reduced and contains inflammatory infiltrate (lymphocytes). Poorly differentiated squamous carcinomas contain more pleomorphic cells and no keratinization.

Prevention

Sunscreen is effective and thus recommended to prevent melanoma and squamous-cell carcinoma. There is little evidence that it is effective in preventing basal-cell carcinoma. Other advice to reduce rates of skin cancer includes avoiding sunburning, wearing protective clothing, sunglasses and hats, and attempting to avoid sun exposure or periods of peak exposure. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends that people between 9 and 25 years of age be advised to avoid ultraviolet light.

The risk of developing skin cancer can be reduced through a number of measures including decreasing indoor tanning and mid day sun exposure, increasing the use of sunscreen, and avoiding the use of tobacco products.

There is insufficient evidence either for or against screening for skin cancers. Vitamin supplements and antioxidant supplements have not been found to have an effect in prevention. Evidence for a benefit from dietary measures is tentative.

Zinc oxide and titanium oxide are often used in sun screen to provide broad protection from UVA and UVB ranges.

Treatment

Treatment is dependent on type of cancer, location of the cancer, age of the person, and whether the cancer is primary or a recurrence. Treatment is also determined by the specific type of cancer. For a small basal-cell cancer in a young person, the treatment with the best cure rate (Mohs surgery or CCPDMA) might be indicated. In the case of an elderly frail man with multiple complicating medical problems, a difficult to excise basal-cell cancer of the nose might warrant radiation therapy (slightly lower cure rate) or no treatment at all. Topical chemotherapy might be indicated for large superficial basal-cell carcinoma for good cosmetic outcome, whereas it might be inadequate for invasive nodular basal-cell carcinoma or invasive squamous-cell carcinoma.. In general, melanoma is poorly responsive to radiation or chemotherapy.

For low-risk disease, radiation therapy (external beam radiotherapy or brachytherapy), topical chemotherapy (imiquimod or 5-fluorouracil) and cryotherapy (freezing the cancer off) can provide adequate control of the disease; all of them, however, may have lower overall cure rates than certain type of surgery. Other modalities of treatment such as photodynamic therapy, topical chemotherapy, electrodesiccation and curettage can be found in the discussions of basal-cell carcinoma and squamous-cell carcinoma.

Mohs' micrographic surgery (Mohs surgery) is a technique used to remove the cancer with the least amount of surrounding tissue and the edges are checked immediately to see if tumor is found. This provides the opportunity to remove the least amount of tissue and provide the best cosmetically favorable results. This is especially important for areas where excess skin is limited, such as the face. Cure rates are equivalent to wide excision. Special training is required to perform this technique. An alternative method is CCPDMA and can be performed by a pathologist not familiar with Mohs surgery.

In the case of disease that has spread (metastasized), further surgical procedures or chemotherapy may be required.

Treatments for metastatic melanoma include biologic immunotherapy agents ipilimumab, pembrolizumab, and nivolumab; BRAF inhibitors, such as vemurafenib and dabrafenib; and a MEK inhibitor trametinib.

Reconstruction

Currently, surgical excision is the most common form of treatment for skin cancers. The goal of reconstructive surgery is restoration of normal appearance and function. The choice of technique in reconstruction is dictated by the size and location of the defect. Excision and reconstruction of facial skin cancers is generally more challenging due to presence of highly visible and functional anatomic structures in the face.

When skin defects are small in size, most can be repaired with simple repair where skin edges are approximated and closed with sutures. This will result in a linear scar. If the repair is made along a natural skin fold or wrinkle line, the scar will be hardly visible. Larger defects may require repair with a skin graft, local skin flap, pedicled skin flap, or a microvascular free flap. Skin grafts and local skin flaps are by far more common than the other listed choices.

Skin grafting is patching of a defect with skin that is removed from another site in the body. The skin graft is sutured to the edges of the defect, and a bolster dressing is placed atop the graft for seven to ten days, to immobilize the graft as it heals in place. There are two forms of skin grafting: split thickness and full thickness. In a split thickness skin graft, a shaver is used to shave a layer of skin from the abdomen or thigh. The donor site regenerates skin and heals over a period of two weeks. In a full thickness skin graft, a segment of skin is totally removed and the donor site needs to be sutured closed.

Split thickness grafts can be used to repair larger defects, but the grafts are inferior in their cosmetic appearance. Full thickness skin grafts are more acceptable cosmetically. However, full thickness grafts can only be used for small or moderate sized defects.

Local skin flaps are a method of closing defects with tissue that closely matches the defect in color and quality. Skin from the periphery of the defect site is mobilized and repositioned to fill the deficit. Various forms of local flaps can be designed to minimize disruption to surrounding tissues and maximize cosmetic outcome of the reconstruction. Pedicled skin flaps are a method of transferring skin with an intact blood supply from a nearby region of the body. An example of such reconstruction is a pedicled forehead flap for repair of a large nasal skin defect. Once the flap develops a source of blood supply form its new bed, the vascular pedicle can be detached.

Prognosis

The mortality rate of basal-cell and squamous-cell carcinoma are around 0.3%, causing 2000 deaths per year in the US. In comparison, the mortality rate of melanoma is 15–20% and it causes 6500 deaths per year. Even though it is much less common, malignant melanoma is responsible for 75% of all skin cancer-related deaths.

Epidemiology

Skin cancers result in 80,000 deaths a year as of 2010, 49,000 of which are due to melanoma and 31,000 of which are due to non-melanoma skin cancers. This is up from 51,000 in 1990.

In the US in 2008, 59,695 people were diagnosed with melanoma, and 8,623 people died from it. In Australia more than 12,500 new cases of melanoma are reported each year, out of which more than 1,500 die from the disease. Australia has the highest per capita incidence of melanoma in the world.

More than 3.5 million cases of skin cancer are diagnosed annually in the United States, which makes it the most common form of cancer in that country. According to the Skin Cancer Foundation, one in five Americans will develop skin cancer at some point of their lives. The most common form of skin cancer is basal-cell carcinoma, followed by squamous cell carcinoma. Although the incidence of many cancers in the United States is falling, the incidence of melanoma keeps growing, with approximately 68,729 melanomas diagnosed in 2004 according to reports of the National Cancer Institute.

Skin cancer (malignant melanoma) is the fifth most common cancer in the UK (around 13,300 people were diagnosed with malignant melanoma in 2011), and the disease accounts for 1% all cancer deaths (around 2,100 people died in 2012).

The survival rate for people with melanoma depends upon when they start treatment. The cure rate is very high when melanoma is detected in early stages, when it can easily be removed surgically. The prognosis is less favorable if the melanoma has spread to other parts of the body.

Australia and New Zealand exhibit one of the highest rates of skin cancer incidence in the world, almost four times the rates registered in the United States, the UK and Canada. Around 434,000 people receive treatment for non-melanoma skin cancers and 10,300 are treated for melanoma. Melanoma is the most common type of cancer in people between 15–44 years in both countries. The incidence of skin cancer has been increasing. The incidence of melanoma among Auckland residents of European descent in 1995 was 77.7 cases per 100,000 people per year, and was predicted to increase in the 21st century because of "the effect of local stratospheric ozone depletion and the time lag from sun exposure to melanoma development."

References

- "Defining Cancer". National Cancer Institute. Retrieved 10 June 2014.

- ^ "Skin Cancer Treatment (PDQ®)". NCI. 25 October 2013. Retrieved 30 June 2014.

- ^ Cakir, BÖ; Adamson, P; Cingi, C (November 2012). "Epidemiology and economic burden of nonmelanoma skin cancer". Facial plastic surgery clinics of North America. 20 (4): 419–22. doi:10.1016/j.fsc.2012.07.004. PMID 23084294.

- ^ Marsden, edited by Sajjad Rajpar, Jerry (2008). ABC of skin cancer. Malden, Mass.: Blackwell Pub. pp. 5–6. ISBN 9781444312508.

{{cite book}}:|first1=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Lynne M Dunphy (2011). Primary Care: The Art and Science of Advanced Practice Nursing. F.A. Davis. p. 242. ISBN 9780803626478.

- ^ "General Information About Melanoma". NCI. 17 April 2014. Retrieved 30 June 2014.

- ^ Gallagher, RP; Lee, TK; Bajdik, CD; Borugian, M (2010). "Ultraviolet radiation". Chronic diseases in Canada. 29 Suppl 1: 51–68. PMID 21199599.

- Maverakis E, Miyamura Y, Bowen MP, Correa G, Ono Y, Goodarzi H (2010). "Light, including ultraviolet". J Autoimmun. 34 (3): J247-57. doi:10.1016/j.jaut.2009.11.011. PMID 20018479.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ World Cancer Report 2014. World Health Organization. 2014. pp. Chapter 5.14. ISBN 9283204298.

- Chiao, EY; Krown, SE (September 2003). "Update on non-acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-defining malignancies". Current opinion in oncology. 15 (5): 389–97. doi:10.1097/00001622-200309000-00008. PMID 12960522.

- ^ Jou, PC; Feldman, RJ; Tomecki, KJ (June 2012). "UV protection and sunscreens: what to tell patients". Cleveland Clinic journal of medicine. 79 (6): 427–36. doi:10.3949/ccjm.79a.11110. PMID 22660875.

- "SEER Stat Fact Sheets: Melanoma of the Skin". NCI. Retrieved 18 June 2014.

- "Release: Cancer Survival Rates, Cancer Survival in England, Patients Diagnosed 2005-2009 and Followed up to 2010". Office for National Statistics. 15 November 2011. Retrieved 30 June 2014.

- Dubas, LE; Ingraffea, A (February 2013). "Nonmelanoma skin cancer". Facial plastic surgery clinics of North America. 21 (1): 43–53. doi:10.1016/j.fsc.2012.10.003. PMID 23369588.

- Leiter, U; Garbe, C (2008). "Epidemiology of melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancer--the role of sunlight". Advances in experimental medicine and biology. 624: 89–103. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-77574-6_8. PMID 18348450.

- "How common is skin cancer?". World Health Organization. Retrieved 30 June 2014.

- "Malignant Melanoma: eMedicine Dermatology".

- Hanson Kerry M.; Gratton Enrico; Bardeen Christopher J (2006). "Sunscreen enhancement of UV-induced reactive oxygen species in the skin". Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 41 (8): 1205–1212. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.06.011. PMID 17015167.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "What You Need To Know About: Melanoma and Other Skin Cancers" (PDF). National Cancer Institute.

- "Melanoma Skin Cancer" (PDF). American Cancer Society. 2012.

- Bickle K, Glass, LF, Messina, JL, Fenske, NA, Siegrist, K (March 2004). "Merkel cell carcinoma: a clinical, histopathologic, and immunohistochemical review". Seminars in cutaneous medicine and surgery. 23 (1): 46–53. doi:10.1016/s1085-5629(03)00087-7. PMID 15095915.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Narayanan DL, Saladi, RN, Fox, JL (September 2010). "Ultraviolet radiation and skin cancer". International Journal of Dermatology. 49 (9): 978–86. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2010.04474.x. PMID 20883261.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Saladi RN, Persaud, AN (January 2005). "The causes of skin cancer: a comprehensive review". Drugs of today (Barcelona, Spain : 1998). 41 (1): 37–53. doi:10.1358/dot.2005.41.1.875777. PMID 15753968.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Wehner, MR; Shive, ML; Chren, MM; Han, J; Qureshi, AA; Linos, E (2 October 2012). "Indoor tanning and non-melanoma skin cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis". BMJ (Clinical research ed.). 345: e5909. doi:10.1136/bmj.e5909. PMC 3462818. PMID 23033409.

- Arndt, K.A. (2010).Skin Care and Repair.Chestnut Hill, MA:Harvard Health Publications.

- Kuschal C, Thoms, KM; Schubert, S; Schäfer, A; Boeckmann, L; Schön, MP; Emmert, S (January 2012). "Skin cancer in organ transplant recipients: effects of immunosuppressive medications on DNA repair". Experimental Dermatology. 21 (1): 2–6. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0625.2011.01413.x. PMID 22151386.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ ""Squamous cell carcinoma (epidermoid carcinoma) — skin" pathologyatlas.ro". Retrieved 21 July 2007.

- Kanavy HE, Gerstenblith MR (December 2011). "Ultraviolet radiation and melanoma". Semin Cutan Med Surg. 30 (4): 222–8. doi:10.1016/j.sder.2011.08.003. PMID 22123420.

- Burnett ME, Wang SQ (April 2011). "Current sunscreen controversies: a critical review". Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 27 (2): 58–67. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0781.2011.00557.x. PMID 21392107.

- Kütting B, Drexler H (December 2010). "UV-induced skin cancer at workplace and evidence-based prevention". Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 83 (8): 843–54. doi:10.1007/s00420-010-0532-4. PMID 20414668.

- Council on Environmental H, Section on, Dermatology, Balk, SJ (March 2011). "Ultraviolet radiation: a hazard to children and adolescents". Pediatrics. 127 (3): 588–97. doi:10.1542/peds.2010-3501. PMID 21357336.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Lin JS, Eder, M, Weinmann, S (February 2011). "Behavioral counseling to prevent skin cancer: a systematic review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force". Annals of Internal Medicine. 154 (3): 190–201. doi:10.1059/0003-4819-154-3-201102010-00009. PMID 21282699.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Lin JS, Eder, M, Weinmann, S (2011). "Behavioral counseling to prevent skin cancer: a systematic review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force". Annals of Internal Medicine. 154 (3): 190–201. doi:10.1059/0003-4819-154-3-201102010-00009. PMID 21282699.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Screening for Skin Cancer". U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. 2009.

- Chang YJ, Myung, SK, Chung, ST, Kim, Y, Lee, EH, Jeon, YJ, Park, CH, Seo, HG, Huh, BY (2011). "Effects of vitamin treatment or supplements with purported antioxidant properties on skin cancer prevention: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". Dermatology (Basel, Switzerland). 223 (1): 36–44. doi:10.1159/000329439. PMID 21846961.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Jensen, JD; Wing, GJ; Dellavalle, RP (November–December 2010). "Nutrition and melanoma prevention". Clinics in dermatology. 28 (6): 644–9. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2010.03.026. PMID 21034988.

- Smijs, Threes G; Pavel, Stanislav (13 October 2011). "Titanium dioxide and zinc oxide nanoparticles in sunscreens: focus on their safety and effectiveness". Nanotechnology, Science and Applications. 4: 95–112. doi:10.2147/NSA.S19419. ISSN 1177-8903. PMC 3781714. PMID 24198489.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - Hill, R; Healy, B; Holloway, L; Kuncic, Z; Thwaites, D; Baldock, C (21 March 2014). "Advances in kilovoltage x-ray beam dosimetry". Physics in medicine and biology. 59 (6): R183-231. doi:10.1088/0031-9155/59/6/r183. PMID 24584183.

- Doherty, Gerard M.; Mulholland, Michael W. (2005). Greenfield's Surgery: Scientific Principles And Practice. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 0-7817-5626-X.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Maverakis E, Cornelius LA, Bowen GM, Phan T, Patel FB, Fitzmaurice S, He Y, Burrall B, Duong C, Kloxin AM, Sultani H, Wilken R, Martinez SR, Patel F (2015). "Metastatic melanoma - a review of current and future treatment options". Acta Derm Venereol. 95 (5): 516–524. doi:10.2340/00015555-2035. PMID 25520039.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Maurice M Khosh, MD, FACS. "Skin Grafts, Full-Thickness". eMedicine.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Skin Cancer Reconstruction

- C. C. Boring, T. S. Squires and T. Tong (1991). "Cancer statistics, 1991". SA Cancer Journal for Clinician. 41 (1): 19–36. doi:10.3322/canjclin.41.1.19. PMID 1984806.

- Jerant AF, Johnson JT, Sheridan CD, Caffrey TJ (July 2000). "Early Detection and Treatment of Skin Cancer". American Family Physician. 62 (2): 357–68, 375–6, 381–2. PMID 10929700.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "WHO Disease and injury country estimates". World Health Organization. 2009. Retrieved 11 November 2009.

- ^ Lozano, R (15 December 2012). "Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010". Lancet. 380 (9859): 2095–128. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0. PMID 23245604.

- CDC - Skin Cancer Statistics

- Melanoma facts and statistics

- "Skin Cancer Facts". Retrieved 2 July 2010.

- "Skin cancer statistics". Cancer Research UK. Retrieved 28 October 2014.

- "Malignant Melanoma Cancer". Retrieved 2 July 2010.

- "Skin Cancer Facts and Figures". Retrieved 1 December 2013.

From 1982 to 2007 melanoma diagnoses increased by around 50%. From 1998 to 2007, GP consultations to treat non-melanoma skin cancer increased by 14%, to reach 950,000 visits each year.

- Jones WO, Harman CR, Ng AKT, Shaw JHF (1999). "Incidence of malignant melanoma in Auckland, New Zealand: The highest rates in the world". World Journal of Surgery. 23 (7): 732–5. doi:10.1007/pl00012378.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

External links

| Overview of tumors, cancer and oncology | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conditions |

| ||||||||||

| Staging/grading | |||||||||||

| Carcinogenesis | |||||||||||

| Misc. | |||||||||||

| Skin cancer of nevi and melanomas | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Melanoma | |||||||||||

| Nevus/ melanocytic nevus | |||||||||||

| Skin cancer of the epidermis | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tumor |

| ||||||||||||||||||

| Other |

| ||||||||||||||||||

| Skin cancer of the dermis | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dermis | |||||||||||||||||

| Subcutaneous tumors |

| ||||||||||||||||

| Tumors and associated structures | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glands |

| ||||||||||

| Hair |

| ||||||||||

| Nails | |||||||||||

Categories: