This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Earl King Jr. (talk | contribs) at 06:41, 26 June 2016 (→Block chain: This sourcing is all wrong Enjoy this complimentary version of Mastering Bitcoin. Purchase and download the DRM-free ebook on oreilly.com.Learn more about the O’Reilly Ebook Advantage. Advert site like Amazon. Not a reliable source). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 06:41, 26 June 2016 by Earl King Jr. (talk | contribs) (→Block chain: This sourcing is all wrong Enjoy this complimentary version of Mastering Bitcoin. Purchase and download the DRM-free ebook on oreilly.com.Learn more about the O’Reilly Ebook Advantage. Advert site like Amazon. Not a reliable source)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)

Logo of the bitcoin reference client Logo of the bitcoin reference client | |

| Unit | |

|---|---|

| Symbol | BTC, XBT, |

| Denominations | |

| Subunit | |

| 10 | millibitcoin |

| 10 | microbitcoin, bit |

| 10 | satoshi |

| Symbol | |

| millibitcoin | mBTC |

| microbitcoin, bit | μBTC |

| Coins | Unspent outputs of transactions denominated in any multiple of satoshis |

| Demographics | |

| Date of introduction | 3 January 2009; 16 years ago (2009-01-03) |

| User(s) | Worldwide |

| Issuance | |

| Administration | Decentralized |

| Valuation | |

| Supply growth | 25 bitcoins per block (approximately every ten minutes) until mid 2016, and then afterwards 12.5 bitcoins per block for 4 years until next halving. This halving continues until 2110–40, when 21 million bitcoins will have been issued. |

Bitcoin is a digital asset and a payment system invented by Satoshi Nakamoto, who published the invention in 2008 and released it as open-source software in 2009.However, Craig Steven Wright has claimed to be the creator of bitcoin. Wright, named himself as the creator of bitcoin, in a BBC news article interview. Wright apparently proved his claim by using 'signature' bitcoins associated with its inventor. Wright said 'his admission is an effort to end speculation about the identity of the originator of the currency.' In December 2015, Wired and Gizmodo, magazines also named Wright as likely to be bitcoin's creator.

The system is peer-to-peer and transactions take place between users directly, without an intermediary. These transactions are verified by network nodes and recorded in a public distributed ledger called the block chain, which uses bitcoin as its unit of account. Since the system works without a central repository or single administrator, the U.S. Treasury categorizes bitcoin as a decentralized virtual currency. Bitcoin is often called the first cryptocurrency, although prior systems existed and it is more correctly described as the first decentralized digital currency. Bitcoin is the largest of its kind in terms of total market value.

Bitcoins are created as a reward for payment processing work in which users offer their computing power to verify and record payments into a public ledger. This activity is called mining and miners are rewarded with transaction fees and newly created bitcoins. Besides being obtained by mining, bitcoins can be exchanged for other currencies, products, and services. When sending bitcoins, users can pay an optional transaction fee to the miners.

In February 2015, the number of merchants accepting bitcoin for products and services passed 100,000. Instead of 2–3% typically imposed by credit card processors, merchants accepting bitcoins often pay fees in the range from 0% to less than 2%. Despite the fourfold increase in the number of merchants accepting bitcoin in 2014, the cryptocurrency did not have much momentum in retail transactions. The European Banking Authority and other sources have warned that bitcoin users are not protected by refund rights or chargebacks. The use of bitcoin by criminals has attracted the attention of financial regulators, legislative bodies, law enforcement, and media. Criminal activities are primarily centered around darknet markets and theft, though officials in countries such as the United States also recognize that bitcoin can provide legitimate financial services.

Etymology and orthography

The word bitcoin occurred in the white paper that defined bitcoin published in 2008. It is a compound of the words bit and coin. The white paper frequently uses the shorter coin.

There is no uniform convention for bitcoin capitalization. Some sources use Bitcoin, capitalized, to refer to the technology and network and bitcoin, lowercase, to refer to the unit of account. The Wall Street Journal, The Chronicle of Higher Education, and the Oxford English Dictionary advocate use of lowercase bitcoin in all cases. This article follows the latter convention.

Design

Units

The unit of account of the bitcoin system is bitcoin. As of 2014, symbols used to represent bitcoin are BTC, XBT, and ![]() . Small amounts of bitcoin used as alternative units are millibitcoin (mBTC), microbitcoin (µBTC), and satoshi. Named in homage to bitcoin's creator, a satoshi is the smallest amount within bitcoin representing 0.00000001 bitcoin, one hundred millionth of a bitcoin. A millibitcoin equals to 0.001 bitcoin, one thousandth of bitcoin. One microbitcoin equals to 0.000001 bitcoin, one millionth of a bitcoin. A microbitcoin is sometimes referred to as a bit.

. Small amounts of bitcoin used as alternative units are millibitcoin (mBTC), microbitcoin (µBTC), and satoshi. Named in homage to bitcoin's creator, a satoshi is the smallest amount within bitcoin representing 0.00000001 bitcoin, one hundred millionth of a bitcoin. A millibitcoin equals to 0.001 bitcoin, one thousandth of bitcoin. One microbitcoin equals to 0.000001 bitcoin, one millionth of a bitcoin. A microbitcoin is sometimes referred to as a bit.

In October 2014, the Bitcoin Foundation disseminated a plan to apply for an ISO 4217 currency code for bitcoin, and mentioned BTC and XBT as the leading candidates.

A proposal was submitted to the Unicode Consortium in October 2015 to add a codepoint for the symbol. It is in the pipeline for position 20BF (₿) in the Currency Symbols block.

Ownership

Ownership of bitcoins implies that a user can spend bitcoins associated with a specific address. To do so, a payer must digitally sign the transaction using the corresponding private key. Without knowledge of the private key, the transaction cannot be signed and bitcoins cannot be spent. The network verifies the signature using the public key.

If the private key is lost, the bitcoin network will not recognize any other evidence of ownership; the coins are then unusable, and thus effectively lost. For example, in 2013 one user claimed to have lost 7,500 bitcoins, worth $7.5 million at the time, when he accidentally discarded a hard drive containing his private key.

Transactions

See also: Bitcoin networkA transaction must have one or more inputs. For the transaction to be valid, every input must be an unspent output of a previous transaction. Every input must be digitally signed. The use of multiple inputs corresponds to the use of multiple coins in a cash transaction. A transaction can also have multiple outputs, allowing one to make multiple payments in one go. A transaction output can be specified as an arbitrary multiple of satoshi. As in a cash transaction, the sum of inputs (coins used to pay) can exceed the intended sum of payments. In such a case, an additional output is used, returning the change back to the payer. Any input satoshis not accounted for in the transaction outputs become the transaction fee.

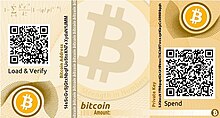

To send money to a bitcoin address, users can click links on webpages; this is accomplished with a provisional bitcoin URI scheme using a template registered with IANA. Bitcoin clients like Electrum and Armory support bitcoin URIs. Mobile clients recognize bitcoin URIs in QR codes, so that the user does not have to type the bitcoin address and amount in manually. The QR code is generated from the user input based on the payment amount. The QR code is displayed on the mobile device screen and can be scanned by a second mobile device.

Mining

Mining is a record-keeping service. Miners keep the block chain consistent, complete, and unalterable by repeatedly verifying and collecting newly broadcast transactions into a new group of transactions called a block. Each block contains a cryptographic hash of the previous block, using the SHA-256 hashing algorithm, which "chains" it to the previous block thus giving the block chain its name.

In order to be accepted by the rest of the network, a new block must contain a so-called proof-of-work. The proof-of-work requires miners to find a number called a nonce, such that when the block content is hashed along with the nonce, the result is numerically smaller than the network's difficulty target. This proof is easy for any node in the network to verify, but extremely time-consuming to generate, as for a secure cryptographic hash, miners must try many different nonce values (usually the sequence of tested values is 0, 1, 2, 3, …) before meeting the difficulty target.

Every 2016 blocks (approximately 14 days), the difficulty target is adjusted based on the network's recent performance, with the aim of keeping the average time between new blocks at ten minutes. In this way the system automatically adapts to the total amount of mining power on the network. For example, between 1 March 2014 and 1 March 2015, the average number of nonces miners had to try before creating a new block increased from 16.4 quintillion to 200.5 quintillion.

The proof-of-work system, alongside the chaining of blocks, makes modifications of the block chain extremely hard, as an attacker must modify all subsequent blocks in order for the modifications of one block to be accepted. As new blocks are mined all the time, the difficulty of modifying a block increases as time passes and the number of subsequent blocks (also called confirmations of the given block) increases.

Practicalities

It has become common for miners to join mining pools, which combine the computational resources of their members in order to increase the frequency of generating new blocks. The reward for each block is then split proportionately among the members, creating a more predictable stream of income for each miner without necessarily changing their long-term average income, although a fee may be charged for the service.

The rewards of mining have led to ever-more-specialized technology being utilized. The most efficient mining hardware makes use of custom designed application-specific integrated circuits, which outperform general-purpose CPUs while using less power. As of 2015, a miner who is not using purpose-built hardware is unlikely to earn enough to cover the cost of the electricity used in their efforts, even if they are a member of a pool.

As of 2015, even if all miners used energy-efficient processors, the combined electricity consumption would be 1.46 terawatt-hours per year—equal to the consumption of about 135,000 American homes. In 2013, electricity use was estimated to be 0.36 terawatt-hours per year or the equivalent of powering 31,000 US homes.

Supply

The successful miner finding the new block is rewarded with newly created bitcoins and transaction fees. As of 28 November 2012, the reward amounted to 25 newly created bitcoins per block added to the block chain. To claim the reward, a special transaction called a coinbase is included with the processed payments. All bitcoins in existence have been created in such coinbase transactions. The bitcoin protocol specifies that the reward for adding a block will be halved every 210,000 blocks (approximately every four years). Eventually, the reward will decrease to zero, and the limit of 21 million bitcoins will be reached c. 2140; the record keeping will then be rewarded by transaction fees solely.

Transaction fees

Paying a transaction fee is optional, but may speed up confirmation of the transaction. Payers have an incentive to include such fees because doing so means their transaction is more likely to be added to the block chain sooner; miners can choose which transactions to process and prioritize those that pay higher fees. Fees are based on the storage size of the transaction generated, which in turn is dependent on the number of inputs used to create the transaction. Furthermore, priority is given to older unspent inputs.

Wallets

See also: Digital wallet

A wallet stores the information necessary to transact bitcoins. While wallets are often described as a place to hold or store bitcoins, due to the nature of the system, bitcoins are inseparable from the block chain transaction ledger. A better way to describe a wallet is something that "stores the digital credentials for your bitcoin holdings" and allows you to access (and spend) them. Bitcoin uses public-key cryptography, in which two cryptographic keys, one public and one private, are generated. At its most basic, a wallet is a collection of these keys.

There are several types of wallets. Software wallets connect to the network and allow spending bitcoins in addition to holding the credentials that prove ownership. Software wallets can be split further in two categories: full clients and lightweight clients.

- Full clients verify transactions directly on a local copy of the block chain (over 65 GB as of April 2016). Because of its size / complexity, the entire block chain is not suitable for all computing devices.

- Lightweight clients on the other hand consult a full client to send and receive transactions without requiring a local copy of the entire block chain (see simplified payment verification – SPV). This makes lightweight clients much faster to setup and allows them to be used on low-power, low-bandwidth devices such as smartphones. When using a lightweight wallet however, the user must trust the server to a certain degree. When using a lightweight client, the server can not steal bitcoins, but it can report faulty values back to the user. With both types of software wallets, the users are responsible for keeping their private keys in a secure place.

Besides software wallets, Internet services called online wallets offer similar functionality but may be easier to use. In this case, credentials to access funds are stored with the online wallet provider rather than on the user's hardware. As a result, the user must have complete trust in the wallet provider. A malicious provider or a breach in server security may cause entrusted bitcoins to be stolen. An example of such security breach occurred with Mt Gox in 2011.

Physical wallets also exist and are more secure, as they store the credentials necessary to spend bitcoins offline. Examples combine a novelty coin with these credentials printed on metal, wood, or plastic. Others are simply paper printouts. Another type of wallet called a hardware wallet keeps credentials offline while facilitating transactions.

Reference implementation

The first wallet program was released in 2009 by Satoshi Nakamoto as open-source code and was originally called bitcoind. Sometimes referred to as the "Satoshi client," this is also known as the reference client because it serves to define the bitcoin protocol and acts as a standard for other implementations. In version 0.5 the client moved from the wxWidgets user interface toolkit to Qt, and the whole bundle was referred to as Bitcoin-Qt. After the release of version 0.9, Bitcoin-Qt was renamed Bitcoin Core.

Privacy

Bitcoin is a pseudonymous currency, meaning that funds are not tied to real-world entities but rather bitcoin addresses. Owners of bitcoin addresses are not explicitly identified, but all transactions on the block chain are public. In addition, transactions can be linked to individuals and companies through "idioms of use" (e.g., transactions that spend coins from multiple inputs indicate that the inputs may have a common owner) and corroborating public transaction data with known information on owners of certain addresses. Additionally, bitcoin exchanges, where bitcoins are traded for traditional currencies, may be required by law to collect personal information.

To heighten financial privacy, a new bitcoin address can be generated for each transaction. For example, hierarchical deterministic wallets generate pseudorandom "rolling addresses" for every transaction from a single seed, while only requiring a single passphrase to be remembered to recover all corresponding private keys. Additionally, "mixing" and CoinJoin services aggregate multiple users' coins and output them to fresh addresses to increase privacy. Researchers at Stanford University and Concordia University have also shown that bitcoin exchanges and other entities can prove assets, liabilities, and solvency without revealing their addresses using zero-knowledge proofs.

Overall, without additional privacy-preserving measures, it has been suggested that bitcoin payments should not be considered more private than credit card payments.

Fungibility

Wallets and similar software technically handle all bitcoins as equivalent, establishing the basic level of fungibility. Researchers have pointed out that the history of each bitcoin is registered and publicly available in the block chain ledger, and that some users may refuse to accept bitcoins coming from controversial transactions, which would harm bitcoin's fungibility. Projects such as Zerocoin and Dark Wallet aim to address these privacy and fungibility issues. The implementation of a proposal for "Confidential Transactions" could increase the fungibility of bitcoins.

History

Main article: History of bitcoin

Bitcoin was invented by Satoshi Nakamoto, who published the invention on 31 October 2008 in a research paper called "Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System". It was implemented as open source code and released in January 2009. Bitcoin is often called the first cryptocurrency although prior systems existed. Bitcoin is more correctly described as the first decentralized digital currency.

Craig Steven Wright has claimed to be the creator of bitcoin. Wright, named himself as the creator of bitcoin in a BBC news interview. Wright apparently proved his claim by using 'signature' bitcoins associated with its inventor. Wright said 'his admission is an effort to end speculation about the identity of the originator of the currency.' In December 2015, Wired and Gizmodo, magazines also named Wright as likely to be bitcoin's creator.

One of the first supporters, adopters, contributor to bitcoin and receiver of the first bitcoin transaction was programmer Hal Finney. Finney downloaded the bitcoin software the day it was released, and received 10 bitcoins from Nakamoto in the world's first bitcoin transaction.

Other early supporters were Wei Dai, creator of bitcoin predecessor b-money, and Nick Szabo, creator of bitcoin predecessor bit gold.

In 2010, an exploit in an early bitcoin client was found that allowed large numbers of bitcoins to be created. The artificially created bitcoins were removed when another chain overtook the bad chain.

Based on bitcoin's open source code, other cryptocurrencies started to emerge in 2011.

In March 2013, a technical glitch caused a fork in the block chain, with one half of the network adding blocks to one version of the chain and the other half adding to another. For six hours two bitcoin networks operated at the same time, each with its own version of the transaction history. The core developers called for a temporary halt to transactions, sparking a sharp sell-off. Normal operation was restored when the majority of the network downgraded to version 0.7 of the bitcoin software.

In 2013 some mainstream websites began accepting bitcoins. WordPress had started in November 2012, followed by OKCupid in April 2013, TigerDirect and Overstock.com in January 2014, Expedia in June 2014, Newegg and Dell in July 2014, and Microsoft in December 2014. The Electronic Frontier Foundation, a non-profit group, started accepting bitcoins in January 2011, stopped accepting them in June 2011, and began again in May 2013.

In May 2013, the Department of Homeland Security seized assets belonging to the Mt. Gox exchange. The U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) shut down the Silk Road website in October 2013.

In October 2013, Chinese internet giant Baidu had allowed clients of website security services to pay with bitcoins. During November 2013, the China-based bitcoin exchange BTC China overtook the Japan-based Mt. Gox and the Europe-based Bitstamp to become the largest bitcoin trading exchange by trade volume. On 19 November 2013, the value of a bitcoin on the Mt. Gox exchange soared to a peak of US$900 after a United States Senate committee hearing was told by the FBI that virtual currencies are a legitimate financial service. On the same day, one bitcoin traded for over RMB¥6780 (US$1,100) in China. On 5 December 2013, the People's Bank of China prohibited Chinese financial institutions from using bitcoins. After the announcement, the value of bitcoins dropped, and Baidu no longer accepted bitcoins for certain services. Buying real-world goods with any virtual currency has been illegal in China since at least 2009.

The first bitcoin ATM was installed in October 2013 in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada.

With about 12 million existing bitcoins in November 2013, the new price increased the market cap for bitcoin to at least US$7.2 billion. By 23 November 2013, the total market capitalization of bitcoin exceeded US$10 billion for the first time.

In the U.S., two men were arrested in January 2014 on charges of money-laundering using bitcoins; one was Charlie Shrem, the head of now defunct bitcoin exchange BitInstant and a vice chairman of the Bitcoin Foundation. Shrem allegedly allowed the other arrested party to purchase large quantities of bitcoins for use on black-market websites.

In early February 2014, one of the largest bitcoin exchanges, Mt. Gox, suspended withdrawals citing technical issues. By the end of the month, Mt. Gox had filed for bankruptcy protection in Japan amid reports that 744,000 bitcoins had been stolen. Originally a site for trading Magic: The Gathering cards, Mt. Gox had once been the dominant bitcoin exchange but its popularity had waned as users experienced difficulties withdrawing funds.

On 18 June 2014, it was announced that bitcoin payment service provider BitPay would become the new sponsor of St. Petersburg Bowl under a two-year deal, renamed the Bitcoin St. Petersburg Bowl. Bitcoin was to be accepted for ticket and concession sales at the game as part of the sponsorship, and the sponsorship itself was also paid for using bitcoin.

Less than one year after the collapse of Mt. Gox, United Kingdom-based exhange Bitstamp announced that their exchange would be taken offline while they investigate a hack which resulted in about 19,000 bitcoins (equivalent to roughly US$5 million at that time) being stolen from their hot wallet. The exchange remained offline for several days amid speculation that customers had lost their funds. Bitstamp resumed trading on 9 January after increasing security measures and assuring customers that their account balances would not be impacted.

The bitcoin exchange service Coinbase launched the first regulated bitcoin exchange in 25 US states on 26 January 2015. At the time of the announcement, CEO Brian Armstrong stated that Coinbase intends to expand to thirty countries by the end of 2015. A spokesperson for Benjamin M. Lawsky, the superintendent of New York state’s Department of Financial Services, stated that Coinbase is operating without a license in the state of New York. Lawsky is responsible for the development of the so-called 'BitLicense', which companies need to acquire in order to legally operate in New York.

In August 2015 it was announced that Barclays would become the first UK high street bank to start accepting bitcoin, with the bank revealing that it plans to allow users to make charitable donations using the currency.

Economics

Classification

According to the director of the Institute for Money, Technology and Financial Inclusion at the University of California-Irvine there is "an unsettled debate about whether bitcoin is a currency". Bitcoin is commonly referred to with terms like: digital currency, digital cash, virtual currency, electronic currency, or cryptocurrency. Its inventor, Satoshi Nakamoto, used the term electronic cash. Bitcoins have three useful qualities in a currency, according to the Economist in January 2015: they are "hard to earn, limited in supply and easy to verify". Economists define money as a store of value, a medium of exchange, and a unit of account and agree that bitcoin has some way to go to meet all these criteria. It does best as a medium of exchange, as of February 2015 the number of merchants accepting bitcoin has passed 100,000. As of March 2014, the bitcoin market suffered from volatility, limiting the ability of bitcoin to act as a stable store of value, and retailers accepting bitcoin use other currencies as their principal unit of account.

Journalists and academics also debate what to call bitcoin. Some media outlets do make a distinction between "real" money and bitcoins, while others call bitcoin real money. The Wall Street Journal declared it a commodity in December 2013. A Forbes journalist referred to it as digital collectible. Two University of Amsterdam computer scientists proposed the term "money-like informational commodity". The Wall Street Journal, Wired, Daily Mail Australia, Forbes, Business Wire and Reuters used the digital asset classification for bitcoin. In a 2016 Forbes article, bitcoin was characterized as a member of a new asset class.

In a 21 September 2015 press release, the US Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) declared bitcoin to be a commodity covered by the Commodity Exchange Act.

The People's Bank of China has stated that bitcoin "is fundamentally not a currency but an investment target".

Buying and selling

Bitcoins can be bought and sold both on- and offline. Participants in online exchanges offer bitcoin buy and sell bids. Using an online exchange to obtain bitcoins entails some risk, and, according to a study published in April 2013, 45% of exchanges fail and take client bitcoins with them. Exchanges have since implemented measures to provide proof of reserves in an effort to convey transparency to users. Offline, bitcoins may be purchased directly from an individual or at a bitcoin ATM.

Price and volatility

According to Mark T. Williams, as of 2014, bitcoin has volatility seven times greater than gold, eight times greater than the S&P 500, and eighteen times greater than the U.S. dollar.

Attempting to explain the high volatility, a group of Japanese scholars stated that there is no stabilization mechanism. The Bitcoin Foundation contends that high volatility is due to insufficient liquidity, while a Forbes journalist claims that it is related to the uncertainty of its long-term value, and the high volatility of a startup currency makes sense, "because people are still experimenting with the currency to figure out how useful it is."

There are uses where volatility does not matter, such as online gambling, tipping, and international remittances. As of 2014, pro-bitcoin venture capitalists argued that the greatly increased trading volume that planned high-frequency trading exchanges would generate is needed to decrease price volatility.

The price of bitcoins has gone through various cycles of appreciation and depreciation referred to by some as bubbles and busts. In 2011, the value of one bitcoin rapidly rose from about US$0.30 to US$32 before returning to US$2. In the latter half of 2012 and during the 2012–13 Cypriot financial crisis, the bitcoin price began to rise, reaching a high of US$266 on 10 April 2013, before crashing to around US$50. On 29 November 2013, the cost of one bitcoin rose to the all-time peak of US$1,242. In 2014, the price fell sharply, and as of April remained depressed at little more than half 2013 prices. As of August 2014 it was under US$600. In January 2015, noting that the bitcoin price had dropped to its lowest level since spring 2013 – around US$224 – The New York Times suggested that "ith no signs of a rally in the offing, the industry is bracing for the effects of a prolonged decline in prices. In particular, bitcoin mining companies, which are essential to the currency’s underlying technology, are flashing warning signs." Also in January 2015, Business Insider reported that deep web drug dealers were "freaking out" as they lost profits through being unable to convert bitcoin revenue to cash quickly enough as the price declined – and that there was a danger that dealers selling reserves to stay in business might force the bitcoin price down further.

On 4 November 2015, bitcoin had risen by more than 20%, exceeding $490. The Financial Times associated the rapid growth with the popularity of "socio-financial networks" MMM operated by Russian businessman Sergei Mavrodi.

According to The Wall Street Journal, as of April 2016, bitcoin is starting to look slightly more stable than gold.

Speculative bubble dispute

Bitcoin has been labelled a speculative bubble by many including former Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan and economist John Quiggin. Nobel Memorial Prize laureate Robert Shiller said that bitcoin "exhibited many of the characteristics of a speculative bubble". Two lead software developers of bitcoin, Gavin Andresen and Mike Hearn, have warned that bubbles may occur. David Andolfatto, a vice president at the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, stated, "Is bitcoin a bubble? Yes, if bubble is defined as a liquidity premium." According to Andolfatto, the price of bitcoin "consists purely of a bubble," but he concedes that many assets have prices that are greater than their intrinsic value. Journalist Matthew Boesler rejects the speculative bubble label and sees bitcoin's quick rise in price as nothing more than normal economic forces at work. The Washington Post pointed out that the observed cycles of appreciation and depreciation don't correspond to the definition of speculative bubble.

Ponzi scheme concerns

Various journalists, economists, and bankers have voiced concerns that bitcoin is a Ponzi scheme. Eric Posner, a law professor at the University of Chicago, stated in 2013 that "a real Ponzi scheme takes fraud; bitcoin, by contrast, seems more like a collective delusion." In 2014 reports by both the World Bank and the Swiss Federal Council examined the concerns and came to the conclusion that bitcoin is not a Ponzi scheme.

Value forecasts

Financial journalists and analysts, economists, and investors have attempted to predict the possible future value of bitcoin. In April 2013, economist John Quiggin stated, "bitcoins will attain their true value of zero sooner or later, but it is impossible to say when". A similar forecast was made in November 2014 by economist Kevin Dowd. In November 2014, David Yermack, Professor of Finance at New York University Stern School of Business, forecast that in November 2015 bitcoin may be all but worthless. In the indicated period bitcoin has exchanged as low as $176.50 (January 2015) and during November 2015 the bitcoin low was $309.90. In December 2013, finance professor Mark T. Williams forecast a bitcoin would be worth less than $10 by July 2014. In the indicated period bitcoin has exchanged as low as $344 (April 2014) and during July 2014 the bitcoin low was $609. In December 2014, Williams said, "The probability of success is low, but if it does hit, the reward will be very large." In May 2013, Bank of America FX and Rate Strategist David Woo forecast a maximum fair value per bitcoin of $1,300. Bitcoin investor Cameron Winklevoss stated in December 2013 that the "small bull case scenario for bitcoin is... 40,000 USD a coin".

Obituaries

The "death" of bitcoin has been proclaimed numerous times. One journalist has recorded 29 such "obituaries" as of early 2015. Forbes magazine declared bitcoin "dead" in June 2011, followed by Gizmodo Australia in August 2011. Wired magazine wrote it had "expired" in December 2012. Ouishare Magazine declared, "game over, bitcoin" in May 2013, and New York Magazine stated bitcoin was "on its path to grave" in June 2013. Reuters published an "obituary" for bitcoin in January 2014. Street Insider declared bitcoin "dead" in February 2014, followed by The Weekly Standard in March 2014, Salon in March 2014, Vice News in March 2014, and Financial Times in September 2014. In January 2015, USA Today states bitcoin was "headed to the ash heap", and The Telegraph declared "the end of bitcoin experiment". In January 2016, former bitcoin developer Mike Hearn called bitcoin a "failed project". Peter Greenhill, Director of E-Business Development for the Isle of Man, commenting on the obituaries paraphrased Mark Twain saying "reports of bitcoin's death have been greatly exaggerated".

Reception

Some economists have responded positively to bitcoin while others have expressed skepticism. François R. Velde, Senior Economist at the Chicago Fed described it as "an elegant solution to the problem of creating a digital currency". Paul Krugman and Brad DeLong have found fault with bitcoin questioning why it should act as a reasonably stable store of value or whether there is a floor on its value. Economist John Quiggin has criticized bitcoin as "the final refutation of the efficient-market hypothesis".

David Andolfatto, Vice President at the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, stated that bitcoin is a threat to the establishment, which he argues is a good thing for the Federal Reserve System and other central banks because it prompts these institutions to operate sound policies.

Free software movement activist Richard Stallman has criticized the lack of anonymity and called for reformed development. PayPal President David A. Marcus calls bitcoin a "great place to put assets" but claims it will not be a currency until price volatility is reduced. Bill Gates, in relation to the cost of moving money from place to place in an interview for Bloomberg L.P. stated: "Bitcoin is exciting because it shows how cheap it can be."

Similarly, Peter Schiff, a bitcoin sceptic understands "the value of the technology as a payment platform" and his Euro Pacific Precious Metals fund partnered with BitPay in May 2014, because "a wire transfer of fiat funds can be slow and expensive for the customer".

Officials in countries such as Brazil, the Isle of Man, Jersey, the United Kingdom, and the United States have recognized its ability to provide legitimate financial services. Recent bitcoin developments have been drawing the interest of more financially savvy politicians and legislators as a result of bitcoin's capability to eradicate fraud, simplify transactions, and provide transparency, when bitcoins are properly utilized.

Acceptance by merchants

In 2015, the number of merchants accepting bitcoin exceeded 100,000. As of December 2014 select firms that accept payments in bitcoin include:

| Alexa rank | Site |

|---|---|

| 33 | PayPal |

| 41 | Microsoft |

| 328 | Dell |

| 329 | Newegg |

| 505 | Overstock.com |

| 512 | Expedia |

| 1,981 | TigerDirect |

| 5,674 | Dish Network |

| 7,038 | Zynga |

| 30,565 | Time Inc. |

| 176,903 | PrivateFly |

| 253,983 | Virgin Galactic |

| 348,010 | Dynamite Entertainment |

| 1,145,668 | Clearly Canadian |

| n.a. | Sacramento Kings |

Acceptance by nonprofits

Organizations accepting donations in bitcoin include: The Electronic Frontier Foundation, Greenpeace, The Mozilla Foundation, and The Wikimedia Foundation. Some U.S. political candidates, including New York City Democratic Congressional candidate Jeff Kurzon have said they would accept campaign donations in bitcoin. In late 2013 the University of Nicosia became the first university in the world to accept bitcoins.

Use in retail transactions

Due to the design of bitcoin, all retail figures are only estimates. According to Tim Swanson, head of business development at a Hong Kong-based cryptocurrency technology company, in 2014, daily retail purchases made with bitcoin were worth about $2.3 million. He estimates that, as of February 2015, fewer than 5,000 bitcoins per day (worth roughly $1.2 million at the time) were being used for retail transactions, and concluded that in 2014 "it appears there has been very little if any increase in retail purchases using bitcoin."

Financial institutions

Bitcoin companies have had difficulty opening traditional bank accounts because lenders have been leery of bitcoin's links to illicit activity. According to Antonio Gallippi, a co-founder of BitPay, "banks are scared to deal with bitcoin companies, even if they really want to". In 2014, the National Australia Bank closed accounts of businesses with ties to bitcoin, and HSBC refused to serve a hedge fund with links to bitcoin. Australian banks in general have been reported as closing down bank accounts of operators of businesses involving the currency; this has become the subject of an investigation by the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission. Nonetheless, Australian banks have keenly adopted the block chain technology on which bitcoin is based. The outcome of any ACCC investigation is yet to be announced.

In a 2013 report, Bank of America Merrill Lynch stated that "we believe bitcoin can become a major means of payment for e-commerce and may emerge as a serious competitor to traditional money-transfer providers."

In June 2014, the first bank that converts deposits in currencies instantly to bitcoin without any fees was opened in Boston.

As an investment

Some Argentinians have bought bitcoins to protect their savings against high inflation or the possibility that governments could confiscate savings accounts. During the 2012–2013 Cypriot financial crisis, bitcoin purchases in Cyprus rose due to fears that savings accounts would be confiscated or taxed. Other methods of investment are bitcoin funds. The first regulated bitcoin fund was established in Jersey in July 2014 and approved by the Jersey Financial Services Commission. Also, c. 2012 an attempt was made by the Winklevoss twins (who in April 2013 claimed they owned nearly 1% of all bitcoins in existence) to establish a bitcoin ETF. As of early 2015, they have announced plans to launch a New York-based bitcoin exchange named Gemini, which has received approval to launch on 5 October 2015. On 4 May 2015, Bitcoin Investment Trust started trading on the OTCQX market as GBTC. Forbes started publishing arguments in favor of investing in December 2015.

In 2013 and 2014, the European Banking Authority and the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA), a United States self-regulatory organization, warned that investing in bitcoins carries significant risks. Forbes named bitcoin the best investment of 2013. In 2014, Bloomberg named bitcoin one of its worst investments of the year. In 2015, bitcoin topped Bloomberg's currency tables.

To improve access to price information and increase transparency, on 30 April 2014 Bloomberg LP announced plans to list prices from bitcoin companies Kraken and Coinbase on its 320,000 subscription financial data terminals. In May 2015, Intercontinental Exchange Inc., parent company of the New York Stock Exchange, announced a bitcoin index initially based on data from Coinbase transactions.

Venture capital

Venture capitalists, such as Peter Thiel's Founders Fund, which invested US$3 million in BitPay, do not purchase bitcoins themselves, instead funding bitcoin infrastructure like companies that provide payment systems to merchants, exchanges, wallet services, etc. In 2012, an incubator for bitcoin-focused start-ups was founded by Adam Draper, with financing help from his father, venture capitalist Tim Draper, one of the largest bitcoin holders after winning an auction of 30,000 bitcoins, at the time called 'mystery buyer'. The company's goal is to fund 100 bitcoin businesses within 2–3 years with $10,000 to $20,000 for a 6% stake. Investors also invest in bitcoin mining. According to a 2015 study by Paolo Tasca, bitcoin startups raised almost $1 billion in three years (Q1 2012 – Q1 2015).

Political economy

The decentralization of money offered by virtual currencies like bitcoin has its theoretical roots in the Austrian school of economics, especially with Friedrich von Hayek in his book Denationalisation of Money: The Argument Refined, in which he advocates a complete free market in the production, distribution and management of money to end the monopoly of central banks.

Bitcoin appeals to tech-savvy libertarians, because it so far exists outside the institutional banking system and the control of governments. However, researchers looking to uncover the reasons for interest in bitcoin did not find evidence in Google search data that this was linked to libertarianism.

Bitcoin's appeal reaches from left wing critics, "who perceive the state and banking sector as representing the same elite interests, recognising in it the potential for collective direct democratic governance of currency" and socialists proposing their "own states, complete with currencies", to right wing critics suspicious of big government, at a time when activities within the regulated banking system were responsible for the severity of the financial crisis of 2007–08, "because governments are not fully living up to the responsibility that comes with state-sponsored money". Bitcoin has been described as "remov the imbalance between the big boys of finance and the disenfranchised little man, potentially allowing early adopters to negotiate favourable rates on exchanges and transfers – something that only the very biggest firms have traditionally enjoyed". Two WSJ journalists describe bitcoin in their book as "about freeing people from the tyranny of centralised trust".

Legal status and regulation

Main article: Legality of bitcoin by countryThe legal status of bitcoin varies substantially from country to country and is still undefined or changing in many of them. While some countries have explicitly allowed its use and trade, others have banned or restricted it. Likewise, various government agencies, departments, and courts have classified bitcoins differently. Regulations and bans that apply to bitcoin probably extend to similar cryptocurrency systems.

In April 2013, Steven Strauss, a Harvard public policy professor, suggested that governments could outlaw bitcoin, and this possibility was mentioned again by a bitcoin investment vehicle in a July 2013 report to a regulator. However, the vast majority of nations have not done so as of 2014. It is illegal in Bangladesh, Bolivia, Ecuador and Russia.

Criminal activity

The use of bitcoin by criminals has attracted the attention of financial regulators, legislative bodies, law enforcement, and the media. The FBI prepared an intelligence assessment, the SEC has issued a pointed warning about investment schemes using virtual currencies, and the U.S. Senate held a hearing on virtual currencies in November 2013. CNN has referred to bitcoin as a "shady online currency starting to gain legitimacy in certain parts of the world", and The Washington Post called it "the currency of choice for seedy online activities".

Several news outlets have asserted that the popularity of bitcoins hinges on the ability to use them to purchase illegal goods. In 2014, researchers at the University of Kentucky found "robust evidence that computer programming enthusiasts and illegal activity drive interest in bitcoin, and find limited or no support for political and investment motives."

Theft

There have been many cases of bitcoin theft. One way this is accomplished involves a third party accessing the private key to a victim's bitcoin address, or of an online wallet. If the private key is stolen, all the bitcoins from the compromised address can be transferred. In that case, the network does not have any provisions to identify the thief, block further transactions of those stolen bitcoins, or return them to the legitimate owner.

Theft also occurs at sites where bitcoins are used to purchase illicit goods. In late November 2013, an estimated $100 million in bitcoins were allegedly stolen from the online illicit goods marketplace Sheep Marketplace, which immediately closed. Users tracked the coins as they were processed and converted to cash, but no funds were recovered and no culprits identified. A different black market, Silk Road 2, stated that during a February 2014 hack, bitcoins valued at $2.7 million were taken from escrow accounts.

Sites where users exchange bitcoins for cash or store them in "wallets" are also targets for theft. Inputs.io, an Australian wallet service, was hacked twice in October 2013 and lost more than $1 million in bitcoins. In late February 2014 Mt. Gox, one of the largest virtual currency exchanges, filed for bankruptcy in Tokyo amid reports that bitcoins worth $350 million had been stolen. Flexcoin, a bitcoin storage specialist based in Alberta, Canada, shut down on March 2014 after saying it discovered a theft of about $650,000 in bitcoins. Poloniex, a digital currency exchange, reported on March 2014 that it lost bitcoins valued at around $50,000. In January 2015 UK-based bitstamp, the third busiest bitcoin exchange globally, was hacked and $5 million in bitcoins were stolen. February 2015 saw a Chinese exchange named BTER lose bitcoins worth nearly $2 million to hackers.

Black markets

Main article: Darknet marketA CMU researcher estimated that in 2012, 4.5% to 9% of all transactions on all exchanges in the world were for drug trades on a single deep web drugs market, Silk Road. Child pornography, murder-for-hire services, and weapons are also allegedly available on black market sites that sell in bitcoin. Due to the anonymous nature and the lack of central control on these markets, it is hard to know whether the services are real or just trying to take the bitcoins.

Several deep web black markets have been shut by authorities. In October 2013 Silk Road was shut down by U.S. law enforcement leading to a short-term decrease in the value of bitcoin. In 2015, the founder of the site was sentenced to life in prison. Alternative sites were soon available, and in early 2014 the Australian Broadcasting Corporation reported that the closure of Silk Road had little impact on the number of Australians selling drugs online, which had actually increased. In early 2014, Dutch authorities closed Utopia, an online illegal goods market, and seized 900 bitcoins. In late 2014, a joint police operation saw European and American authorities seize bitcoins and close 400 deep web sites including the illicit goods market Silk Road 2.0. Law enforcement activity has resulted in several convictions. In December 2014, Charlie Shrem was sentenced to two years in prison for indirectly helping to send $1 million to the Silk Road drugs site, and in February 2015, its founder, Ross Ulbricht, was convicted on drugs charges and faces a life sentence.

Some black market sites may seek to steal bitcoins from customers. The bitcoin community branded one site, Sheep Marketplace, as a scam when it prevented withdrawals and shut down after an alleged bitcoins theft. In a separate case, escrow accounts with bitcoins belonging to patrons of a different black market were hacked in early 2014.

According to the Internet Watch Foundation, a UK-based charity, bitcoin is used to purchase child pornography, and almost 200 such websites accept it as payment. Bitcoin isn't the sole way to purchase child pornography online, as Troels Oertling, head of the cybercrime unit at Europol, states, "Ukash and Paysafecard... have been used to pay for such material." However, the Internet Watch Foundation lists around 30 sites that exclusively accept bitcoins. Some of these sites have shut down, such as a deep web crowdfunding website that aimed to fund the creation of new child porn. Furthermore, hyperlinks to child porn websites have been added to the block chain as arbitrary data can be included when a transaction is made.

Money laundering

Bitcoins may not be ideal for money laundering because all transactions are public. Authorities, including the European Banking Authority the FBI, and the Financial Action Task Force of the G7 have expressed concerns that bitcoin may be used for money laundering. In early 2014, an operator of a U.S. bitcoin exchange was arrested for money laundering. A report by UK's Treasury and Home Office named "UK national risk assessment of money laundering and terrorist financing" (2015 October) found that, of the twelve methods examined in the report, bitcoin carries the lowest risk of being used for money laundering, with the most common money laundering method being the banks.

Ponzi scheme

In a Ponzi scheme that utilized bitcoins, The Bitcoin Savings and Trust promised investors up to 7 percent weekly interest, and raised at least 700,000 bitcoins from 2011 to 2012. In July 2013 the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission charged the company and its founder in 2013 "with defrauding investors in a Ponzi scheme involving bitcoin". In September 2014 the judge fined Bitcoin Savings & Trust and its owner $40 million for operating a bitcoin Ponzi scheme.

Malware

Bitcoin-related malware includes software that steals bitcoins from users using a variety of techniques, software that uses infected computers to mine bitcoins, and different types of ransomware, which disable computers or prevent files from being accessed until some payment is made. Security company Dell SecureWorks said in February 2014 that it had identified almost 150 types of bitcoin malware.

Unauthorized mining

In June 2011, Symantec warned about the possibility that botnets could mine covertly for bitcoins. Malware used the parallel processing capabilities of GPUs built into many modern video cards. Although the average PC with an integrated graphics processor is virtually useless for bitcoin mining, tens of thousands of PCs laden with mining malware could produce some results.

In mid-August 2011, bitcoin mining botnets were detected, and less than three months later, bitcoin mining trojans had infected Mac OS X.

In April 2013, electronic sports organization E-Sports Entertainment was accused of hijacking 14,000 computers to mine bitcoins; the company later settled the case with the State of New Jersey.

German police arrested two people in December 2013 who customized existing botnet software to perform bitcoin mining, which police said had been used to mine at least $950,000 worth of bitcoins.

For four days in December 2013 and January 2014, Yahoo! Europe hosted an ad containing bitcoin mining malware that infected an estimated two million computers. The software, called Sefnit, was first detected in mid-2013 and has been bundled with many software packages. Microsoft has been removing the malware through its Microsoft Security Essentials and other security software.

Several reports of employees or students using university or research computers to mine bitcoins have been published.

Malware stealing

Some malware can steal private keys for bitcoin wallets allowing the bitcoins themselves to be stolen. The most common type searches computers for cryptocurrency wallets to upload to a remote server where they can be cracked and their coins stolen. Many of these also log keystrokes to record passwords, often avoiding the need to crack the keys. A different approach detects when a bitcoin address is copied to a clipboard and quickly replaces it with a different address, tricking people into sending bitcoins to the wrong address. This method is effective because bitcoin transactions are irreversible.

One virus, spread through the Pony botnet, was reported in February 2014 to have stolen up to $220,000 in cryptocurrencies including bitcoins from 85 wallets. Security company Trustwave, which tracked the malware, reports that its latest version was able to steal 30 types of digital currency.

A type of Mac malware active in August 2013, Bitvanity posed as a vanity wallet address generator and stole addresses and private keys from other bitcoin client software. A different trojan for Mac OS X, called CoinThief was reported in February 2014 to be responsible for multiple bitcoin thefts. The software was hidden in versions of some cryptocurrency apps on Download.com and MacUpdate.

Ransomware

Another type of bitcoin-related malware is ransomware. One program called CryptoLocker, typically spread through legitimate-looking email attachments, encrypts the hard drive of an infected computer, then displays a countdown timer and demands a ransom, usually two bitcoins, to decrypt it. Massachusetts police said they paid a 2 bitcoin ransom in November 2013, worth more than $1,300 at the time, to decrypt one of their hard drives. Linkup, a combination ransomware and bitcoin mining program that surfaced in February 2014, disables internet access and demands credit card information to restore it, while secretly mining bitcoins.

Security

Various potential attacks on the bitcoin network and its use as a payment system, real or theoretical, have been considered. The bitcoin protocol includes several features that protect it against some of those attacks, such as unauthorized spending, double spending, forging bitcoins, and tampering with the block chain. Other attacks, such as theft of private keys, require due care by users.

Unauthorized spending

Unauthorized spending is mitigated by bitcoin's implementation of public-private key cryptography. For example; when Alice sends a bitcoin to Bob, Bob becomes the new owner of the bitcoin. Eve observing the transaction might want to spend the bitcoin Bob just received, but she cannot sign the transaction without the knowledge of Bob's private key.

Double spending

A specific problem that an internet payment system must solve is double-spending, whereby a user pays the same coin to two or more different recipients. An example of such a problem would be if Eve sent a bitcoin to Alice and later sent the same bitcoin to Bob. The bitcoin network guards against double-spending by recording all bitcoin transfers in a ledger (the block chain) that is visible to all users, and ensuring for all transferred bitcoins that they haven't been previously spent.

Race attack

If Eve offers to pay Alice a bitcoin in exchange for goods and signs a corresponding transaction, it is still possible that she also creates a different transaction at the same time sending the same bitcoin to Bob. By the rules, the network accepts only one of the transactions. This is called a race attack, since there is a race which transaction will be accepted first. Alice can reduce the risk of race attack stipulating that she will not deliver the goods until Eve's payment to Alice appears in the block chain.

A variant race attack (which has been called a Finney attack by reference to Hal Finney) requires the participation of a miner. Instead of sending both payment requests (to pay Bob and Alice with the same coins) to the network, Eve issues only Alice's payment request to the network, while the accomplice tries to mine a block that includes the payment to Bob instead of Alice. There is a positive probability that the rogue miner will succeed before the network, in which case the payment to Alice will be rejected. As with the plain race attack, Alice can reduce the risk of a Finney attack by waiting for the payment to be included in the block chain.

History modification

The other principal way to steal bitcoins would be to modify block chain ledger entries.

For example, Eve could buy something from Alice, like a sofa, by adding a signed entry to the block chain ledger equivalent to Eve pays Alice 5 bitcoins. Later, after receiving the sofa, Eve could modify that block chain ledger entry to read instead: Eve pays Alice 0.05 bitcoins, or replace Alice's address by another of Eve's addresses. Digital signatures cannot prevent this attack: Eve can simply sign her entry again after modifying it.

To prevent modification attacks, each block of transactions that is added to the block chain includes a cryptographic hash code that is computed from the hash of the previous block as well as all the information in the block itself. When the bitcoin software notices two competing block chains, it will automatically assume that the chain with the greatest amount of work to produce it is the valid one. Therefore, in order to modify an already recorded transaction (as in the above example), the attacker would have to recalculate not just the modified block, but all the blocks after the modified one, until the modified chain contains more work than the legitimate chain that the rest of the network has been building in the meantime. Consequently, for this attack to succeed, the attacker must outperform the honest part of the network.

Each block that is added to the block chain, starting with the block containing a given transaction, is called a confirmation of that transaction. Ideally, merchants and services that receive payment in bitcoin should wait for at least one confirmation to be distributed over the network, before assuming that the payment was done. The more confirmations that the merchant waits for, the more difficult it is for an attacker to successfully reverse the transaction in a block chain—unless the attacker controls more than half the total network power, in which case it is called a 51% attack. For example, if the attacker possesses 10% of the calculation power of the bitcoin network and the shop requires 6 confirmations for a successful transaction, the probability of success of such an attack will be 0.02428%.

Selfish mining

This attack was first introduced by Ittay Eyal and Emin Gun Sirer at the beginning of November 2013. In this attack, the attacker finds blocks but does not broadcast them. Instead, the attacker mines their own private chain and later (when another miner or network of miners finds their own block) publishes several private blocks in a row. This forces the "honest" network to abandon their previous work and switch to the attacker's branch. As a result, honest miners lose a significant part of their revenue, causing a relatively greater proportion of blocks in the block chain to be of the attacker's work and thereby increasing the attacker's profits.

According to the authors, the profit margin of the selfish miner grows superlinearly with the attacker's hashpower; thus if a rational miner observes and joins the selfish miner's pool, both miners' profits will increase (thus giving both the rational miner an incentive to join and the selfish miner an incentive to accept the join). This makes the attack and incentives even stronger, potentially leading to a 51% attack and the collapse of the currency.

Gavin Andresen and Ed Felten disagreed with this conclusion, Felten defending his assertion that the bitcoin protocol is incentive compatible. The original authors responded that the disagreement stemmed from Felten's misunderstanding of how miners are compensated in mining pools, that the assertion was in error, given the presence of a strategy that dominates honest mining, and that the error stemmed from Felten et al. not modeling block withholding attacks in their analysis.

Deanonymisation of clients

Along with transaction graph analysis, which may reveal connections between bitcoin addresses (pseudonyms), there is a possible attack which links a user's pseudonym to its IP address. If the peer is using Tor, the attack includes a method to separate the peer from the Tor network, forcing them to use their real IP address for any further transactions. The attack makes use of bitcoin mechanisms of relaying peer addresses and anti-DoS protection. The cost of the attack on the full bitcoin network is under €1500 per month.

Other uses

In May 2015 NASDAQ OMX Group announced a pilot study using bitcoins of negligible value, called "colored coins", to represent and transfer pre-IPO trading shares on its Nasdaq Private Markets. Blockstream has proposed to add sidechains to the bitcoin ecosystem to enable a wider set of features.

Data in the block chain

While it is possible to store any digital file in the block chain, the larger the transaction size, the larger any associated fees become. Various items have been embedded, including URLs to child pornography, an ASCII art image of Ben Bernanke, material from the Wikileaks cables, prayers from bitcoin miners, and the original bitcoin whitepaper.

In academia

In the fall of 2014, undergraduate students at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) each received bitcoins worth $100 "to better understand this emerging technology". The bitcoins were not provided by MIT but rather the MIT Bitcoin Club, a student-run club. Similar initiatives have been created by students and groups at other universities, such as Stanford University and the University of California, Berkeley.

In art, entertainment, and media

Fine arts

The Museum of Applied Arts, Vienna purchased a work by Dutch artist Harm van den Dorpel in 2015 and became the first museum to acquire art work using bitcoin.

Films

A documentary film called The Rise and Rise of Bitcoin (late 2014) features interviews with people who use bitcoin, such as a computer programmer and a drug dealer.

Music

Several lighthearted songs celebrating bitcoin have been released.

Literature

In Charles Stross' science fiction novel Neptune's Brood (2014), a modification of bitcoin is used as the universal interstellar payment system. The functioning of the system is a major plot element of the book.

Radio

On 25 April 2013, the weekly Mexican Public Radio technology program, 1060 Interfase produced by Radio Educación, broadcast two shows dedicated to bitcoin.

Television

- In early 2015, the CNN series Inside Man featured an episode about bitcoin. Filmed in July 2014, it featured Morgan Spurlock living off of bitcoins for a week to figure out whether the world is ready for a new kind of money.

- In Season 3, the CBS show The Good Wife featured an episode alluding to the creator of bitcoin as well as the FBI investigating the case. The episode titled 'Bitcoin for Dummies' was shown in early 2012.

- The CBS series CSI: Cyber featured an episode about bitcoin during its first season, entitled "Bit by Bit". The plot focused on the theft of bitcoins from a small family-run business.

- In November 2015, on the reality television show Judge Judy a bitcoin trader lost a case where he had claimed to be involved in an elaborate man-in-the-middle scheme.

- In the episode "The Old College Try" of the TV series Scorpion, the series' team must stop a cyber terrorist, using code written by college students, who is threatening to shut down the Federal Reserve if they don't receive a quarter of a billion bitcoin in the next 72 hours.

- In February 2016, a Vietnamese action movie was released under the name Bitcoins Heist. Bitcoins Heist focuses on "a team of criminals" assembled to catch a man wanted by intergovernmental police organization Interpol.

Bibliography

- Paul Vigna; Michael Casey (27 January 2015). The Age of Cryptocurrency: How Bitcoin and Digital Money Are Challenging the Global Economic Order. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 1-250-06563-1.

- Nathaniel Popper (19 May 2015). Digital Gold: Bitcoin and the Inside Story of the Misfits and Millionaires Trying to Reinvent Money. HarperCollins Publishers. ISBN 978-0-06-236249-0.

- Andreas Antonopoulos (3 December 2014). Mastering Bitcoin. O'Reilly Media. ISBN 978-1-4493-7404-4.

See also

Template:Misplaced Pages books

- Alternative currency

- Bitcoin Center NYC

- Bitcoin Classic

- Bitcoin XT

- Coinscrum

- Crypto-anarchism

- Decentralized autonomous organization

- Digital gold currency

- Private currency

- World currency

Notes

- ^ As of 2014, BTC is a commonly used code. It does not conform to ISO 4217 as BT is the country code of Bhutan.

- ^ As of 2014, XBT, a code that conforms to ISO 4217 though is not officially part of it, is used by Bloomberg L.P., CNNMoney, and xe.com.

- ^ The proposal for the addition of bitcoin sign

has been accepted by Unicode.

has been accepted by Unicode.

- Bitcoin does not have a central authority.

- ^ DigiCash was first used for a transaction in 1994, and OpenCoin, now known as Ripple, had code written prior to November 2008.

- Relative mining difficulty is defined as the ratio of the difficulty target on 9 January 2009 to the current difficulty target.

- It is misleading to think that there is an analogy between gold mining and bitcoin mining. The fact is that gold miners are rewarded for producing gold, while bitcoin miners are not rewarded for producing bitcoins; they are rewarded for their record-keeping services.

- The exact number is 20,999,999.9769 bitcoins.

- ^ Some of these firms use bitcoin payment processors such as BitPay and Coinbase and do not handle or store bitcoins themselves.

- The price of 1 bitcoin in U.S. dollars.

- Volatility is calculated on a yearly basis.

- Retailers usually offer in-store credit, instead of a return transfer (or chargeback) as the only option when customers return items purchased with bitcoins.

References

- ^ Nermin Hajdarbegovic (7 October 2014). "Bitcoin Foundation to Standardise Bitcoin Symbol and Code Next Year". CoinDesk. Retrieved 28 January 2015.

- Romain Dillet (9 August 2013). "Bitcoin Ticker Available On Bloomberg Terminal For Employees". TechCrunch. Retrieved 2 November 2014.

- "Bitcoin Composite Quote (XBT)". CNN Money. CNN. Retrieved 2 November 2014.

- "XBT – Bitcoin". xe.com. Retrieved 2 November 2014.

- Shirriff, Ken (2 October 2015). "Proposal for addition of bitcoin sign" (PDF). unicode.org. Unicode. Retrieved 3 November 2015.

- Cawrey, Daniel (9 April 2014). "Industry group aims to change bitcoin symbol to 'Ƀ'". CoinDesk.

- ^ Andreas M. Antonopoulos (April 2014). Mastering Bitcoin. Unlocking Digital Crypto-Currencies. O'Reilly Media. Retrieved 23 October 2014.

- Garzik, Jeff (2 May 2014). "BitPay, Bitcoin, and where to put that decimal point". Retrieved 20 November 2015.

- ^ Jason Mick (12 June 2011). "Cracking the Bitcoin: Digging Into a $131M USD Virtual Currency". Daily Tech. Retrieved 30 September 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Statement of Jennifer Shasky Calvery, Director Financial Crimes Enforcement Network United States Department of the Treasury Before the United States Senate Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs Subcommittee on National Security and International Trade and Finance Subcommittee on Economic Policy". fincen.gov. Financial Crimes Enforcement Network. 19 November 2013. Retrieved 1 June 2014.

- ^ Ron Dorit; Adi Shamir (2012). "Quantitative Analysis of the Full Bitcoin Transaction Graph" (PDF). Cryptology ePrint Archive. Retrieved 18 October 2012.

- ^ Casey, Michael J. (11 March 2015). "Ex-J.P. Morgan CDS Pioneer Blythe Masters To Head Bitcoin-Related Startup". Markets. The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 19 November 2015.

- ^ Nakamoto, Satoshi (October 2008). "Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System" (PDF). bitcoin.org. Retrieved 28 April 2014.

- Davis, Joshua (10 October 2011). "The Crypto-Currency: Bitcoin and its mysterious inventor". The New Yorker. Retrieved 31 October 2014.

- http://www.foxbusiness.com/markets/2016/05/02/australian-craig-wright-said-to-be-bitcoin-inventor-bbc.html Retrieved June-25-2016

- ^ Jerry Brito; Andrea Castillo (2013). "Bitcoin: A Primer for Policymakers" (PDF). Mercatus Center. George Mason University. Retrieved 22 October 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - Joshua Kopstein (12 December 2013). "The Mission to Decentralize the Internet". The New Yorker. Retrieved 30 December 2014.

The network's "nodes"—users running the bitcoin software on their computers—collectively check the integrity of other nodes to ensure that no one spends the same coins twice. All transactions are published on a shared public ledger, called the "block chain"

- ^ "Drug market moving quickly online, global user survey finds". South China Morning Post. South China Morning Post Publishers. 14 April 2014. Retrieved 7 January 2015.

- ^ Sparkes, Matthew (9 June 2014). "The coming digital anarchy". The Telegraph. London: Telegraph Media Group Limited. Retrieved 7 January 2015.

- ^ Lachance Shandrow, Kim (30 May 2014). "This Company Is Now the Largest in the World to Accept Bitcoin". entrepreneur.com. Entrepreneur Media, Inc. Retrieved 7 January 2015.

- "World's first electronic cash payment over computer networks". Electronic Frontier Foundation. 26 May 1994. Retrieved 20 November 2015.

- "OpenCoin/opencoin-historic". github.com. GitHub, Inc. Retrieved 8 May 2015.

- ^ Sagona-Stophel, Katherine. "Bitcoin 101 white paper" (PDF). Thomson Reuters. Retrieved 20 November 2015.

- ^ Espinoza, Javier (22 September 2014). "Is It Time to Invest in Bitcoin? Cryptocurrencies Are Highly Volatile, but Some Say They Are Worth It". Journal Reports. The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 3 November 2014.

- "What is Bitcoin?". CNN Money. Retrieved 16 November 2015.

- Natasha Lomas (16 September 2013). "BitPay Passes 10,000 Bitcoin-Accepting Merchants On Its Payment Processing Network". Techcrunch. Techcrunch.com. Retrieved 21 October 2013.

- ^ Joshua A. Kroll; Ian C. Davey; Edward W. Felten (11–12 June 2013). "The Economics of Bitcoin Mining, or Bitcoin in the Presence of Adversaries" (PDF). The Twelfth Workshop on the Economics of Information Security (WEIS 2013). Retrieved 26 April 2016.

A transaction fee is like a tip or gratuity left for the miner.

- ^ Cuthbertson, Anthony (4 February 2015). "Bitcoin now accepted by 100,000 merchants worldwide". International Business Times. IBTimes Co., Ltd. Retrieved 20 November 2015.

- Wingfield, Nick (30 October 2013). "Bitcoin Pursues the Mainstream". The New York Times. Retrieved 4 November 2013.

- ^ Orcutt, Mike (18 February 2015). "Is Bitcoin Stalling?". MIT Technology Review. Retrieved 20 February 2015.

- ^ "Warning to consumers on virtual currencies". European Banking Authority. 12 December 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 December 2013. Retrieved 23 December 2013.

- ^ Lavin, Tim (8 August 2013). "The SEC Shows Why Bitcoin Is Doomed". bloomberg.com. Bloomberg LP. Retrieved 20 October 2013.

- Tracy, Ryan (5 November 2013). "Bitcoin Comes Under Senate Scrutiny". Washington Wire. Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 20 December 2014.

- ^ "Bitcoins Virtual Currency: Unique Features Present Challenges for Deterring Illicit Activity" (PDF). Cyber Intelligence Section and Criminal Intelligence Section. FBI. 24 April 2012. Retrieved 2 November 2014.

- ^ Timothy B. Lee; Hayley Tsukayama (2 October 2013). "Authorities shut down Silk Road, the world's largest Bitcoin-based drug market". The Washington Post. Retrieved 21 October 2013.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Tracy, Ryan (18 November 2013). "Authorities See Worth of Bitcoin". Markets. The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 28 November 2014.

- ^ "bitcoin". Oxford University Press. Retrieved 28 December 2014.

- ^ Bustillos, Maria (2 April 2013). "The Bitcoin Boom". The New Yorker. Condé Nast. Retrieved 22 December 2013.

Standards vary, but there seems to be a consensus forming around Bitcoin, capitalized, for the system, the software, and the network it runs on, and bitcoin, lowercase, for the currency itself.

- Vigna, Paul (3 March 2014). "BitBeat: Is It Bitcoin, or bitcoin? The Orthography of the Cryptography". WSJ. Retrieved 21 April 2014.

- Metcalf, Allan (14 April 2014). "The latest style". Lingua Franca blog. The Chronicle of Higher Education (chronicle.com). Retrieved 19 April 2014.

- "Regulation of Bitcoin in Selected Jurisdictions" (PDF). The Law Library of Congress, Global Legal Research Center. January 2014. Retrieved 26 August 2014.

- Katie Pisa; Natasha Maguder (9 July 2014). "Bitcoin your way to a double espresso". cnn.com. CNN. Retrieved 23 April 2015.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - "Press Release October 7, 2014: Bitcoin Foundation Financial Standards Working Group Leads the Way for Mainstream Bitcoin Adoption". Press Release. Bitcoin Foundation. 7 October 2014. Retrieved 7 November 2014.

- "Proposal for addition of bitcoin sign" (PDF). Retrieved 16 May 2016.

- "Man Throws Away 7,500 Bitcoins, Now Worth $7.5 Million". CBS DC. 29 November 2013. Retrieved 23 January 2014.

- Don W. Tyler, Jeff Isenhart, Anne Mueller, Christoph Sadil (8 May 2014). "Qr code-enabled p2p payment systems and methods.US 20140129428 A1" (Patent application). uspto.gov. Retrieved 20 January 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Charts". Blockchain.info. Retrieved 2 November 2014.

- ^ Andolfatto, David (31 March 2014). "Bitcoin and Beyond: The Possibilities and Pitfalls of Virtual Currencies" (PDF). Dialogue with the Fed. Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Retrieved 16 April 2014.

- "Difficulty History" (The ratio of all hashes over valid hashes is D x 4295032833, where D is the published "Difficulty" figure.). Blockchain.info. Retrieved 26 March 2015.

- ^ Ramzan, Zulfikar (2014). "Bitcoin: What is it?". The Khan Academy. Retrieved 5 April 2014.

- Mills, Kelly (3 April 2014). "Bitcoins lose viability". The Arbiter. Boise State Student Media. Retrieved 14 April 2014.

- Wang, Luqin; Liu, Yong. "Exploring Miner Evolution in Bitcoin Network" (PDF). NYU Polytechnic School of Engineering. Retrieved 15 February 2015.

- Rosenfeld, Meni. "Analysis of Bitcoin Pooled Mining Reward Systems" (PDF). Retrieved 14 February 2015.

- Peter Svensson (17 June 2014). "Bitcoin faces biggest threat yet: a miner takeover". Retrieved 8 January 2015.

- Rockman, Simon (17 January 2014). "Manic miners: Ten Bitcoin generating machines". The Register. Retrieved 13 February 2014.

- Bays, Jason (9 April 2014). "Bitcoin offers speedy currency, poses high risks". Purdue Exponent. The Exponent Online. Retrieved 14 April 2014.

- "The magic of mining". The economist. 13 January 2015. Retrieved 13 January 2015.

- Gimein, Mark (13 April 2013). "Virtual Bitcoin Mining Is a Real-World Environmental Disaster". Bloomberg Business. Bloomberg LP. Retrieved 22 April 2015.

- Ashlee Vance (14 November 2013). "2014 Outlook: Bitcoin Mining Chips, a High-Tech Arms Race". Businessweek. Retrieved 24 November 2013.

- "Block #210000". Blockchain.info. Retrieved 20 November 2015.

- Ritchie S. King; Sam Williams; David Yanofsky (17 December 2013). "By reading this article, you're mining bitcoins". qz.com. Atlantic Media Co. Retrieved 17 December 2013.

- "How much will the transaction fee be?". FAQ. Bitcoin Foundation. Retrieved 19 March 2014.

- ^ "How much will the transaction fee be?". Bitcoinfees.com. Retrieved 30 November 2014.

- Adam Serwer; Dana Liebelson (10 April 2013). "Bitcoin, Explained". motherjones.com. Mother Jones. Retrieved 26 April 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Villasenor, John (26 April 2014). "Secure Bitcoin Storage: A Q&A With Three Bitcoin Company CEOs". forbes.com. Forbes. Retrieved 26 April 2014.

- ^ "Bitcoin: Bitcoin under pressure". The Economist. 30 November 2013. Retrieved 30 November 2013.

- ^ Skudnov, Rostislav (2012). Bitcoin Clients (PDF) (Bachelor's Thesis). Turku University of Applied Sciences. Retrieved 16 January 2014.

- "Blockchain Size". Blockchain.info. Retrieved 24 April 2016.

- Jon Matonis (26 April 2012). "Be Your Own Bank: Bitcoin Wallet for Apple". Forbes. Retrieved 17 November 2014.

- Bill Barhydt (4 June 2014). "3 reasons Wall Street can't stay away from bitcoin". NBCUniversal. Retrieved 2 April 2015.

- "Major Attack on the World's Largest Bitcoin Exchange". blog.zorinaq.com. 19 June 2011. Retrieved 14 April 2016.

- Staff, Verge (13 December 2013). "Casascius, maker of shiny physical bitcoins, shut down by Treasury Department". The Verge. Retrieved 10 January 2014.

- Staff, Coindesk (13 April 2015). "Finnish Startup Launches 'Low-Cost' Physical Bitcoins". Coindesk. Retrieved 13 April 2015.

- Eric Mu (15 October 2014). "Meet Trezor, A Bitcoin Safe That Fits Into Your Pocket". Forbes Asia. Forbes. Retrieved 31 October 2014.

- "Bitcoin-Qt/bitcoind version 0.5.0". Bitcointalk. Retrieved 6 May 2015.

- "Bitcoin Core version 0.9.0 released". bitcoin.org. Retrieved 8 January 2015.

- Simonite, Tom (5 September 2013). "Mapping the Bitcoin Economy Could Reveal Users' Identities". MIT Technology Review. Retrieved 2 April 2014.

- ^ Lee, Timothy (21 August 2013). "Five surprising facts about Bitcoin". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2 April 2014.

- McMillan, Robert (6 June 2013). "How Bitcoin lets you spy on careless companies". wired.co.uk. Conde Nast. Retrieved 2 April 2014.

- Potts, Jake (31 July 2015). "Mastering Bitcoin Privacy". Airbitz. Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- Matonis, Jon (5 June 2013). "The Politics Of Bitcoin Mixing Services". forbes.com. Forbes. Retrieved 2 April 2014.

- Gaby G. Dagher, Benedikt Bünz, Joseph Bonneau, Jeremy Clark and Dan Boneh (26 October 2015). "Provisions: Privacy-preserving proofs of solvency for Bitcoin exchanges" (PDF). International Association for Cryptologic Research. Retrieved 23 February 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Bar-El, Hagai (3 April 2014). "Bitcoin does not provide anonymity". Archived from the original on 7 April 2014. Retrieved 26 April 2015.