This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Sagecandor (talk | contribs) at 16:01, 25 November 2016 (it is already in the citation itself). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 16:01, 25 November 2016 by Sagecandor (talk | contribs) (it is already in the citation itself)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) This article is about intentionally fraudulent websites. For satirical websites, see news satire.

Fake news websites publish hoaxes and fraudulent misinformation to drive web traffic inflamed by social media. These sites are distinguished from news satire because they intend to mislead and profit from readers believing the stories to be true. U.S. News & World Report warned that fraudulent news often took the form of outright hoaxes and propaganda, while BuzzFeed called the problem an "epidemic of misinformation".

Fraudulent articles grew popular through social media sharing sites during the 2016 presidential election in the United States. Two independent teams of expert researchers tracked fraudulent news reporting and subsequent amplification through social media during the 2016 U.S. election to Russia. These conclusions by the nonpartisan foreign policy expert group PropOrNot and independently by the Foreign Policy Research Institute were confirmed by prior research from the Elliott School of International Affairs at George Washington University and by the RAND Corporation. A significant amount of the deceptive pieces were written by teenagers operating out of a small town in the country of Macedonia. After experimenting with fraudulent articles from a liberal perspective about Bernie Sanders, the Macedonian teenagers found their most popular pieces were about Donald Trump. During the 2016 election cycle such fake news articles were shared by high-profile Trump advocates including son and campaign surrogate Eric Trump, top national security adviser Michael T. Flynn, and then-campaign managers Kellyanne Conway and Corey Lewandowski.

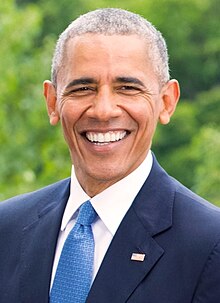

Google CEO Sundar Pichai agreed that fraudulent news sites likely swayed the results of the 2016 U.S. election. President of the United States Barack Obama said in November 2016 that a disregard for facts on social media created a "dust cloud of nonsense". In response to the fraudulent news problem, Google responded on 14 November 2016 by banning such companies from profiting on through its marketing program AdSense. After this decisive action on Google's part, Facebook followed suit with a similar action a day later. Neither company took action to block the pervasiveness of fraudulent news sites in their search engine results pages or web feeds.

Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg stated it was a "crazy idea" that services such as Facebook could have swayed results of the 2016 U.S. election. Facebook staffers dismayed by the company's inaction formed their own secret group to address the problem themselves. These secret staffers told BuzzFeed, "he knows, and those of us at the company know, that fake news ran wild on our platform during the entire campaign season." A number of commentators, including The New York Times writer Zeynep Tufekci, MIT Technology Review contributor Jamie Condliffe, and Dartmouth College political scientist Brendan Nyhan, viewed Facebook's response to the spread of fake news as inadequate. After such criticism, Zuckerberg made a second statement on the matter, and BuzzFeed subsequently advised Facebook users they could report fraudulent news to the company.

Prominent sites

See also: List of fake news websites and Clickbait

Prominent among fraudulent news sites include false propaganda created by individuals in the countries of Russia, Macedonia, and Romania. In addition another popular purveyor of fraudulent reports, "Ending the Fed", was run by a 24-year-old named Ovidiu Drobota out of Romania, who boasted to Inc. magazine about being more popular than "the mainstream media". The majority of fraudulent news during the 2016 United States election cycle came from adolescent youths in Macedonia attempting to rapidly profit from those believing their falsehoods. An investigation by BuzzFeed revealed that over 100 websites spreading fraudulent articles supportive of Donald Trump were created by teenagers in the town of Veles, Macedonia. The Macedonian teenagers experimented with writing fraudulent news about Bernie Sanders and other articles from a politically left or liberal slant; they quickly found out that their most popular fraudulent writings were about Donald Trump.

The Guardian performed its own independent investigation and reached the same conclusion as BuzzFeed; concurrently tracing back over 150 fraudulent news sites to the same exact town of Veles, Macedonia. One of the Macedonian teenagers, "Alex", was interviewed by The Guardian during the ongoing election cycle in August 2016 and stated that regardless of whether Trump won or lost the election fraudulent news websites would remain profitable. He explained he often began writing his pieces by plagiarism through copy and pasting direct content from other websites. Alex told The Guardian: "I think my traffic will be fine if Trump doesn’t win. There are too many haters on the net, and all of my audience hates Hillary."

One prominent fraudulent news story—that protesters at anti-Trump rallies in Austin, Texas, were "bused in"—started as a tweet by one individual with 40 Twitter followers. Over the next three days, the tweet was shared at least 16,000 times on Twitter and 350,000 times on Facebook, and promoted in the conservative blogosphere, before the individual stated that he had fabricated his assertions.

BuzzFeed called the problem an "epidemic of misinformation". According to BuzzFeed's analysis, the 20 top-performing election news stories from fraudulent sites generated more shares, reactions, and comments on Facebook than the 20 top-performing stories from 19 major news outlets.

Fox News host of the journalism meta analysis television program Media Buzz, Howard Kurtz, acknowledged fraudulent news was a serious problem. Kurtz relied heavily upon the BuzzFeed analysis for his reporting on the controversy. Kurtz wrote that: "Facebook is polluting the media environment with garbage". Citing the BuzzFeed investigation, Kurtz pointed out: "The legit stuff drew 7,367,000 shares, reactions and comments, while the fictional material drew 8,711,000 shares, reactions and comments." Kurtz concluded Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg must admit the website is a media company: "But once Zuckerberg admits he’s actually running one of the most powerful media brands on the planet, he has to get more aggressive about promoting real news and weeding out hoaxers and charlatans. The alternative is to watch Facebook’s own credibility decline."

U.S. News & World Report warned readers to be wary of popular fraudulent news sites composed of either outright hoaxes or propaganda, and recommended the website Fake News Watch for a listing of such problematic sources.

One of the investigative journalists who exposed the ties between fraudulent websites and Macedonian teenagers, Craig Silverman of BuzzFeed News, told Public Radio International that some false stories net the Balkan adolescents a few thousand dollars per day and most fake articles aggregate to earn them on average a few thousand per month. Public Radio International reported that after the 2016 election season the teenagers from Macedonia would likely turn back to making money off fraudulent medical advice websites, which Silverman noted was where most of the youths had garnered clickbait revenues before the election season.

Impact

Russia

Further information: Russian propaganda and Cyberwarfare by Russia

In 2015, the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe released an analysis highly critical of disinformation campaigns by Russia employed to appear as legitimate news reporting. These propaganda campaigns by Russia were intended to interfere with Ukraine relations with Europe — after the removal of former Ukraine president Viktor Yanukovych from power. According to Deutsche Welle, "The propaganda in question employed similar tactics used by fake news websites during the US elections, including misleading headlines, fabricated quotes and misreporting". This propaganda motivated the European Union to create a special taskforce to deal with disinformation campaigns originating out of Russia.

Foreign Policy reported that the taskforce, called East StratCom Team, "employs 11 mostly Russian speakers who scour the web for fake news and send out biweekly reviews highlighting specific distorted news stories and tactics." The European Union voted to add to finances for the taskforce in November 2016.

Deutsche Welle noted: "Needless to say, the issue of fake news, which has been used to garner support for various political causes, poses a serious danger to the fabric of democratic societies, whether in Europe, the US or any other nation across the globe."

Journalist Adrian Chen observed a strange pattern in December 2015 whereby online accounts he had been monitoring as supportive of Russia had suddenly additionally become highly supportive of 2016 U.S. presidential candidate Donald Trump. Chen said: "I created this list of Russian trolls. And I check on it once in a while, still. And a lot of them have turned into conservative accounts, like fake conservatives. I don’t know what’s going on, but they’re all tweeting about Donald Trump and stuff." The Daily Beast reported in August 2016: "Fake news stories from Kremlin propagandists regularly become social media trends." Writers Andrew Weisburd and Clint Watts observed: "The synchronization of hacking and social media information operations not only has the ability to promote a favored candidate, like Trump, but also has the potential to incite unrest amongst American communities."

Gleb Pavlovsky, who assisted in created an propaganda program for the Russian government prior to 2008, told The New York Times in August 2016: "Moscow views world affairs as a system of special operations, and very sincerely believes that it itself is an object of Western special operations. I am sure that there are a lot of centers, some linked to the state, that are involved in inventing these kinds of fake stories."

Anders Lindberg, a Swedish attorney and reporter, explained a common pattern of fake news distribution: "The dynamic is always the same: It originates somewhere in Russia, on Russia state media sites, or different websites or somewhere in that kind of context. Then the fake document becomes the source of a news story distributed on far-left or far-right-wing websites. Those who rely on those sites for news link to the story, and it spreads. Nobody can say where they come from, but they end up as key issues in a security policy decision."

In 2016, the European Parliament Committee on Foreign Affairs passed a resolution in the European Parliament warning of the use by Russia of tools including: "pseudo-news agencies ... social media and internet trolls" as forms of propaganda and disinformation in an attempt to lessen democratic values. The resolution emphatically requested media experts within the European Union to investigate, explaining: "with the limited awareness amongst some of its member states, that they are audiences and arenas of propaganda and disinformation." The resolution condemned Russian sources for publicizing "absolutely fake" news reports, and the tally on 23 November 2016 passed by a margin of 304 votes to 179.

On 24 November 2016, The Washington Post reported that two independent teams of expert researchers confirmed that propaganda during the 2016 U.S. presidential election organized by Russia helped foment criticism of Democrat candidate Hillary Clinton and support of Republican candidate Donald Trump through deliberate proliferation of fake news. The propaganda tactic by Russia included social media users, Internet trolls working for hire, botnets, and organized websites in order to cast Clinton in a negative light. Foreign Policy Research Institute fellow Clint Watts monitored propaganda from Russia and stated its tactics were similar to those used during the Cold War — only this time spread deliberately through social media to a more powerful extent. Watts stated the goal of Russia was: "They want to essentially erode faith in the U.S. government or U.S. government interests." Watts research along with colleagues Andrew Weisburd and J.M. Berger was published in November 2016.

Separately, the nonpartisan foreign policy expert group PropOrNot came to similar conclusions about involvement by Russia in propagating fake news during the 2016 U.S. election. PropOrNot analyzed data from Twitter and Facebook and tracked propaganda from the disinformation campaign by Russia to a national reach of 15 million people within the United States. PropOrNot concluded that accounts belonging to both Russia Today and Sputnik News promoted "false and misleading stories in their reports", and additionally magnified other false articles found on the Internet to support their propaganda effort. The executive director of PropOrNot told The Washington Post: "The way that this propaganda apparatus supported Trump was equivalent to some massive amount of a media buy. It was like Russia was running a super PAC for Trump’s campaign. ... It worked." The conclusions of both the separate investigations by Foreign Policy Research Institute and PropOrNot were confirmed by prior research from the Elliott School of International Affairs at George Washington University and by the RAND Corporation.

Sweden

The Swedish Security Service issued a report in 2015 identifying propaganda from Russia infiltrating Sweden with the objective to: "spread pro-Russian messages and to exacerbate worries and create splits in society."

The Ministry of Defence of Sweden organization the Swedish Civil Contingencies Agency (MSB) identified fake news reports targeting Sweden in 2016 which originated from Russia. Swedish Civil Contingencies Agency official Mikael Tofvesson stated: "This is going on all the time. The pattern now is that they pump out a constant narrative that in some respects is negative for Sweden."

The Local identified these tactics as a form of psychological warfare. The newspaper reported the MSB identified Russia Today and Sputnik News as "important channels for fake news". As a result of growth in this propaganda in Sweden, the MSB planned to hire six additional security officials to fight back against the campaign of fraudulent information.

2016 U.S. presidential election

Fraudulent stories during the 2016 U.S. presidential election popularized on Facebook included a viral post that Pope Francis had endorsed Donald Trump, and another that wrote actor Denzel Washington "backs Trump in the most epic way possible".

Donald Trump's son and campaign surrogate Eric Trump, top national security adviser Michael T. Flynn, and then-campaign managers Kellyanne Conway and Corey Lewandowski shared fake news stories during the campaign. Paul Horner, a creator of fraudulent news stories, stated in an interview with The Washington Post that he was making approximately US$10,000 a month through advertisements linked to the fraudulent news. He claimed to have posted a fraudulent advertisement to Craigslist offering thousands of dollars in payment to protesters, and to have written a story based on this which was later shared online by Trump's campaign manager. Horner believed that when the stories were shown to be false, this would reflect badly on Trump's supporters who had shared them, but concluded "Looking back, instead of hurting the campaign, I think I helped it. And that feels ."

U.S. President Barack Obama commented on the significant problem of fraudulent information on social networks impacting elections, in a speech the day before Election Day in 2016: "The way campaigns have unfolded, we just start accepting crazy stuff as normal. And people, if they just repeat attacks enough and outright lies over and over again, as long as it’s on Facebook, and people can see it, as long as its on social media, people start believing it. And it creates this dust cloud of nonsense."

Shortly after the election, Obama again commented on the problem, saying in an appearance with German Chancellor Angela Merkel: "If we are not serious about facts and what’s true and what's not, and particularly in an age of social media when so many people are getting their information in sound bites and off their phones, if we can't discriminate between serious arguments and propaganda, then we have problems."

Indonesia and Philippines

Fraudulent news has been particularly problematic in Indonesia and the Philippines, where social media has an outsized political influence. According to experts, "many developing countries with populations new to both democracy and social media" are particularly vulnerable to the influence of fraudulent news. In some developing countries, "Facebook even offers free smartphone data connections to basic public online services, some news sites and Facebook itself — but limits access to broader sources that could help debunk fake news."

Germany

Angela Merkel, the Chancellor of Germany, lamented the problem of fraudulent news reports in a November 2016 speech days after announcing her campaign for a fourth term as leader of her country. In a speech to the German parliament, Merkel was critical of such fake sites: "Something has changed -- as globalisation has marched on, (political) debate is taking place in a completely new media environment. Opinions aren't formed the way they were 25 years ago. Today we have fake sites, bots, trolls -- things that regenerate themselves, reinforcing opinions with certain algorithms and we have to learn to deal with them." She warned that such fraudulent news websites were a force increasing the power of political extremist populism. Merkel called fraudulent news a growing phenomenon that might need to be regulated in the future.

Google and Facebook actions

After the 2016 election, the top result on Google for results of the race was to a fraudulent news site. With regards to the false results posted on the website "70 News", Google admitted its prominence in search results was a mistake: "In this case we clearly didn't get it right, but we are continually working to improve our algorithms."

When asked shortly after the election whether fraudulent news sites had changed the results of the election, Google CEO Sundar Pichai responded: "Sure" and went on to emphasize the importance of stopping the spread of fraudulent news sites: "Look, it is important to remember this was a very close election and so, just for me, so looking at it scientifically, one in a hundred voters voting one way or the other swings the election either way. ... From our perspective, there should just be no situation where fake news gets distributed, so we are all for doing better here."

On 14 November 2016, Google responded to the growing problem of fraudulent news sites by banning such companies from profiting on advertising from traffic to false articles through its marketing program AdSense. The company already had a policy for denying ads for dieting ripoffs and counterfeit merchandise. Google stated upon the announcement: "We’ve been working on an update to our publisher policies and will start prohibiting Google ads from being placed on misrepresentative content. Moving forward, we will restrict ad serving on pages that misrepresent, misstate, or conceal information about the publisher, the publisher’s content, or the primary purpose of the web property."

Facebook made the decision to take a similar move the following day. Facebook explained its new policy: "We do not integrate or display ads in apps or sites containing content that is illegal, misleading or deceptive, which includes fake news. ... We have updated the policy to explicitly clarify that this applies to fake news. Our team will continue to closely vet all prospective publishers and monitor existing ones to ensure compliance."

Although the steps by both Google and Facebook intended to deny ad revenue to fraudulent news sites, neither company took actions to prevent dissemination of false stories in search engine results pages or web feeds.

Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg said in a post to his website on the issue, the notion that fraudulent news sites impacted the 2016 election was a "crazy idea". Zuckerberg rejected that his website played any role in the outcome of the election, describing the idea that it might have done so as "pretty crazy". In a blog post, he also stated that more than 99% of content on Facebook was authentic (i.e. neither fake news nor a hoax). In the same blog post, he stated that "News and media are not the primary things people do on Facebook, so I find it odd when people insist we call ourselves a news or media company in order to acknowledge its importance."

Top staff members at Facebook did not feel that simply blocking ad revenue from these fraudulent sites was a strong enough response to the problem, and together they made an executive decision and created a secret group to deal with the issue themselves. In response to Zuckerberg's first statement that fraudulent news did not impact the 2016 election, the secret Facebook response group disputed this idea: "It’s not a crazy idea. What’s crazy is for him to come out and dismiss it like that, when he knows, and those of us at the company know, that fake news ran wild on our platform during the entire campaign season." BuzzFeed reported that the secret task force included "dozens" of Facebook employees.

Facebook faced mounting criticism in the days after its decision to solely revoke advertising revenues from fraudulent news providers, and not take any further actions on the matter. After one week negative coverage in the media including assertions that the proliferation of fraudulent news on Facebook gave the 2016 U.S. presidential election to Donald Trump, Mark Zuckerberg posted a second post on the issue on 18 November 2016. The post was a reversal of his earlier comments on the matter where he had discounted the impact of fraudulent news.

Zuckerberg asserted there was an inherent difficult nature in attempting to filter out fraudulent news: "The problems here are complex, both technically and philosophically. We believe in giving people a voice, which means erring on the side of letting people share what they want whenever possible." The New York Times reported some measures being considered and not yet implemented by Facebook included: "third-party verification services, better automated detection tools and simpler ways for users to flag suspicious content." The 18 November post did not announce any concrete actions the company would definitively take, or when such measures would formally be put into usage on the website.

Many people commented positively under Zuckerberg's second post on fraudulent news. National Public Radio observed the changes being considered by Facebook to identify fraud constituted progress for the company into a new medium: "Together, the projects signal another step in Facebook's evolution from its start as a tech-oriented company to its current status as a complex media platform."

On 19 November 2016, BuzzFeed advised Facebook users they could report posts from fraudulent news websites. Users could do so by choosing the report option: "I think it shouldn't be on Facebook", followed by: "It’s a false news story."

Response from fact-checking websites

Further information: FactCheck.org, PolitiFact.com, and Snopes.comFact-checking websites play a role as debunkers to fraudulent news reports. Such sites saw large increases in readership and web traffic during the 2016 U.S. election cycle. FactCheck.org, PolitiFact.com, Snopes.com, and "The Fact Checker" section of The Washington Post, are prominent fact-checking websites that played an important role in debunking fraud. CNN media meta analyst Brian Stelter wrote: "In journalism circles, 2016 is the year of the fact-checker."

By the close of the 2016 U.S. election season, fact-checking websites FactCheck.org, PolitiFact.com, and Snopes.com, had each authored guides on how to respond to fraudulent news. FactCheck.org advised readers to check the source, author, date, and headline of publications. They also recommended their colleagues Snopes.com, The Washington Post Fact Checker, and PolitiFact.com as important resources to rely upon before re-sharing a fraudulent story. FactCheck.org admonished consumers to be wary of their own biases when viewing media they agree with. PolitiFact.com announced they would tag stories as "Fake news" so that readers could view all fraudulent stories they had debunked. Snopes.com warned readers: "So long as social media allows for the rapid spread of information, manipulative entities will seek to cash in on the rapid spread of misinformation."

The Washington Post's "The Fact Checker" section, which is dedicated to evaluating the truth of political claims, greatly increased in popularity during the 2016 election cycle. Glenn Kessler, who runs the Post's "Fact Checker", wrote that "fact-checking websites all experienced huge surges in readership during the election campaign." The Fact Checker had five times more unique visitors than during the 2012 cycle." Kessler cited research showing that fact-checks are effective at reducing "the prevalence of a false belief." Will Moy, director of the London-based Full Fact, a UK fact-checking website, said that debunking must take place over a sustained period of time to truly be effective.

FactCheck.org former director Brooks Jackson remarked that larger media companies had devoted increased focus to the importance of debunking fraud during the 2016 election: "It's really remarkable to see how big news operations have come around to challenging false and deceitful claims directly. It's about time." FactCheck.org began a new partnership with CNN journalist Jake Tapper in 2016 to examine the veracity of reported claims by candidates.

Angie Drobnic Holan, editor of PolitiFact.com, noted the circumstances warranted support for the practice: "All of the media has embraced fact-checking because there was a story that really needed it." Holan was heartened that fact-checking garnered increased viewership for those engaged in the practice: "Fact-checking is now a proven ratings getter. I think editors and news directors see that now. So that's a plus." Holan cautioned that heads of media companies must strongly support the practice of debunking, as it often provokes hate mail and extreme responses from zealots.

On 17 November 2016, the International Fact-Checking Network (IFCN) published an open letter on the website of the Poynter Institute to Facebook founder and CEO Mark Zuckerberg, imploring him to utilize fact-checkers in order to help identify fraud on Facebook. Created in September 2015, the IFCN is housed within the St. Petersburg, Florida-based Poynter Institute for Media Studies and aims to support the work of 64 member fact-checking organizations around the world. Alexios Mantzarlis, co-founder of FactCheckEU.org and former managing editor of Italian fact-checking site Pagella Politica, was named director and editor of IFCN in September 2015. Signatories to the 2016 letter to Zuckerberg featured a global representation of fact-checking groups, including: Africa Check, FactCheck.org, PolitiFact.com, and The Washington Post Fact Checker. The groups wrote they were eager to assist Facebook root out fraudulent news sources on the website.

In his second post on the matter on 18 November 2016, Zuckerberg responded to the fraudulent news problem by suggesting usage of fact-checking websites. He specifically identified fact-checking website Snopes.com, and pointed out that Facebook monitors links to such debunking websites in reply comments as a method to determine which original posts were fraudulent. Zuckerberg explained: "Anyone on Facebook can report any link as false, and we use signals from those reports along with a number of others — like people sharing links to myth-busting sites such as Snopes — to understand which stories we can confidently classify as misinformation. Similar to clickbait, spam and scams, we penalize this content in News Feed so it's much less likely to spread."

Academic analysis

Writing for MIT Technology Review, Jamie Condliffe said that merely banning ad revenue from the fraudulent news sites was not enough action by Facebook to effectively deal with the problem. He wrote: "The post-election furor surrounding Facebook’s fake-news problem has sparked new initiatives to halt the provision of ads to sites that peddle false information. But it’s only a partial solution to the problem: for now, hoaxes and fabricated stories will continue to appear in feeds." Condliffe concluded: "Clearly Facebook needs to do something to address the issue of misinformation, and it’s making a start. But the ultimate solution is probably more significant, and rather more complex, than a simple ad ban."

Indiana University informatics and computer science professor Fil Menczer commented on the steps by Google and Facebook to deny fraudulent news sites advertising revenue: "One of the incentives for a good portion of fake news is money. This could cut the income that creates the incentive to create the fake news sites."

Dartmouth College political scientist Brendan Nyhan has criticized Facebook for "doing so little to combat fake news... Facebook should be fighting misinformation, not amplifying it."

Zeynep Tufekci wrote critically about Facebook's stance on fraudulent news sites in a piece for The New York Times, pointing out fraudulent websites in Macedonia profited handsomely off false stories about the 2016 U.S. election: "The company's business model, algorithms and policies entrench echo chambers and fuel the spread of misinformation."

Merrimack College assistant professor of media studies Melissa Zimdars wrote an article "False, Misleading, Clickbait-y and Satirical 'News' Sources" in which she advised how to determine if a fraudulent source was a fake news site. This included: strange domain names, websites ending in "lo" or "com.co", lack of author attribution, inspect the "About Us" page, poor website layout and style of ALL CAPS.

Education and history professor Sam Wineburg of the Stanford Graduate School of Education at Stanford University and colleague Sarah McGrew authored a 2016 study which analyzed students' ability to discern fraudulent news from factual reporting. The study took place over a year-long period of time, and involved a sample size of over 7,800 responses from university, secondary and middle school students in 12 states within the United States. The researchers were "shocked" at the "stunning and dismaying consistency" with which students thought fraudulent news reports were factual in nature. The authors concluded the solution was to educate consumers of media on the Internet to themselves behave like fact-checkers — and actively question the veracity of all sources they encounter online.

Media commentary

Samantha Bee went to Russia for her television show Full Frontal with Samantha Bee and met with individuals financed by the government of Russia to act as Internet trolls and attempt to subvert the 2016 U.S. election in order to subvert democracy. The man and woman interviewed by Bee said they influenced the election by commenting on websites for New York Post, The Wall Street Journal, The Washington Post, Twitter, and Facebook. They kept their identities covert, and maintained cover identities separate from their real Russian names, with the woman claiming in posts to be a housewife residing in Nebraska. They blamed consumers for believing all they read online.

Executive producers for Full Frontal with Samantha Bee told The Daily Beast that they relied upon writer Adrian Chen, who had previously reported on Russian trolls for The New York Times Magazine in 2015, as a resource to contact those in Russia agreeable to be interviewed by Bee. The Russian trolls requested to wear masks on camera and to maintain the confidentiality of all of their fake accounts so they would not be publicly identified. Full Frontal with Samantha Bee executive producers paid the Russian trolls to utilize the Twitter hashtag #SleazySam in order to troll the show itself — so that the production staff could verify the trolls were indeed able to manipulate content online as they claimed.

Subsequent to their research within Russia itself for a second segment on Full Frontal with Samantha Bee, the production staff came to the conclusion that Russian leader Vladimir Putin supported Donald Trump for U.S. President in order to subvert the system of democracy within the U.S. Television producer Razan Ghalayini explained to The Daily Beast: "Russia is an authoritarian regime and authoritarian regimes don’t benefit from the vision of democracy being the best version of governance." Television producer Miles Kahn concurred with this analysis, adding: "It’s not so much that Putin wants Trump. He probably prefers him in the long run, but he would almost rather the election be contested. They want chaos."

Critics contended that fraudulent news on Facebook may have been responsible for Donald Trump winning the 2016 U.S. election, because most of the fake news stories Facebook allowed to spread portrayed him in a positive light. Facebook is not liable for posting or publicizing fake content because, under the Communications Decency Act, interactive computer services cannot be held responsible for information provided by another internet entity. Some legal experts, like Keith Altman, think that Facebook's huge scale creates such a large potential for fake news to spread that this law may need to be changed.

John Oliver commented on his comedy program Last Week Tonight with John Oliver that the problem of fraudulent news sites fed into a wider issue of echo chambers in the media. Oliver lamented: "Fake facts circulate on social media to a frightening extent." He pointed out such sites often only exist to draw in profit from web traffic: "There is now a whole cottage industry specializing in hyper-partisan, sometimes wildly distorted clickbait."

New York magazine contributor Brian Feldman responded to the article by Melissa Zimdars, and used her list to create a Google Chrome extension that would warn users about fraudulent news sites. He invited others to use his code and improve upon it.

BBC News interviewed a fraudulent news site writer who went by the pseudonym "Chief Reporter (CR)", who defended his actions and possible influence on elections: "If enough of an electorate are in a frame of mind where they will believe absolutely everything they read on the internet, to a certain extent they have to be prepared to deal with the consequences."

Slate magazine senior technology editor Will Oremus wrote that though fraudulent news sites were controversial, their prevalence was obscuring a wider discussion about the negative impact on society from those who only consume media from one particular tailored viewpoint — and therefore perpetuate filter bubbles.

See also

- 2016 Democratic National Committee email leak

- Post-truth politics

- Clickbait

- Confirmation bias

- Criticism of Facebook

- Criticism of Google

- Cyberwarfare by Russia

- Democratic National Committee cyber attacks

- Disinformation

- Echo chamber (media)

- Fancy Bear

- Filter bubble

- Guccifer 2.0

- Podesta emails

- Russian espionage in the United States

- Russian propaganda

- Selective exposure theory

- Spiral of silence

- State-sponsored Internet propaganda

- Tribe (internet)

- Trolls from Olgino

- Web brigades

Footnotes

- FactCheck.org is a nonprofit organization and a project of the Annenberg Public Policy Center of the Annenberg School for Communication at the University of Pennsylvania. FactCheck.org won a 2010 Sigma Delta Chi Award from the Society of Professional Journalists for reporting on deceptive claims made about the federal health care legislation.

- PolitiFact.com is a fact-checking project by the Tampa Bay Times. PolitiFact.com received a 2009 Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting for its fact-checking efforts the previous year.

- Snopes.com is a fact-checking website operated by Barbara and David Mikkelson. It was given "high praise" by competitor and colleague site FactCheck.org. In a meta analysis of fact-checking websites, Network World gave Snopes.com a grade of "A", and concluded: "go-to destination when something seems too good or bad to be true".

- "The Fact Checker" is a project by The Washington Post to analyze political claims. Their colleagues and competitors at FactCheck.org recommended The Fact Checker as a resource to use before assuming a story is factual.

References

- ^ Timberg, Craig (24 November 2016), "Russian propaganda effort helped spread 'fake news' during election, experts say", The Washington Post, retrieved 25 November 2016,

Two teams of independent researchers found that the Russians exploited American-made technology platforms to attack U.S. democracy at a particularly vulnerable moment

- ^ LaCapria, Kim (2 November 2016), "Snopes' Field Guide to Fake News Sites and Hoax Purveyors - Snopes.com's updated guide to the internet's clickbaiting, news-faking, social media exploiting dark side.", Snopes.com, retrieved 19 November 2016

- ^ Rachel Dicker (14 November 2016), "Avoid These Fake News Sites at All Costs", U.S. News & World Report, retrieved 16 November 2016

- ^ Ishmael N. Daro and Craig Silverman (15 November 2016), "Fake News Sites Are Not Terribly Worried About Google Kicking Them Off AdSense", BuzzFeed, retrieved 16 November 2016

- ^ Craig Silverman and Lawrence Alexander (3 November 2016), "How Teens In The Balkans Are Duping Trump Supporters With Fake News", BuzzFeed, retrieved 16 November 2016,

As a result, this strange hub of pro-Trump sites in the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia is now playing a significant role in propagating the kind of false and misleading content that was identified in a recent BuzzFeed News analysis of hyperpartisan Facebook pages.

- ^ Dan Tynan (24 August 2016), "How Facebook powers money machines for obscure political 'news' sites - From Macedonia to the San Francisco Bay, clickbait political sites are cashing in on Trumpmania – and they're getting a big boost from Facebook", The Guardian, retrieved 18 November 2016

- ^ Dewey, Caitlin (17 November 2016), "Facebook fake-news writer: 'I think Donald Trump is in the White House because of me'", The Washington Post, ISSN 0190-8286, retrieved 17 November 2016

- ^ Drum, Kevin (17 November 2016), "Meet Ret. General Michael Flynn, the Most Gullible Guy in the Army", Mother Jones, retrieved 18 November 2016

- ^ Tapper, Jake (17 November 2016), "Fake news stories thriving on social media - Phony news stories are thriving on social media, so much so President Obama addressed it. CNN's Jake Tapper reports.", CNN, retrieved 18 November 2016

- ^ Masnick, Mike (14 October 2016), "Donald Trump's Son & Campaign Manager Both Tweet Obviously Fake Story", Techdirt, retrieved 18 November 2016

- ^ Avery Hartmans (15 November 2016), "Google's CEO says fake news could have swung the election", Business Insider, retrieved 16 November 2016

- ^ John Ribeiro (14 November 2016), "Zuckerberg says fake news on Facebook didn't tilt the elections", Computerworld, retrieved 16 November 2016

- ^ "Google and Facebook target fake news sites with advertising clampdown", Belfast Telegraph, 15 November 2016, retrieved 16 November 2016

- ^ Shanika Gunaratna (15 November 2016), "Facebook, Google announce new policies to fight fake news", CBS News, retrieved 16 November 2016

- ^ Paul Blake (15 November 2016), "Google, Facebook Move to Block Fake News From Ad Services", ABC News, retrieved 16 November 2016

- ^ Gina Hall (15 November 2016), "Facebook staffers form an unofficial task force to look into fake news problem", Silicon Valley Business Journal, retrieved 16 November 2016

- ^ Douglas Perry (15 November 2016), "Facebook, Google try to drain the fake-news swamp without angering partisans", The Oregonian, retrieved 16 November 2016

- ^ Jamie Condliffe (15 November 2016), "Facebook's Fake-News Ad Ban Is Not Enough", MIT Technology Review, retrieved 16 November 2016

- ^ Craig Silverman (16 November 2016), "Viral Fake Election News Outperformed Real News On Facebook In Final Months Of The US Election", BuzzFeed, retrieved 16 November 2016

- ^ Silverman, Craig (19 November 2016), "This Is How You Can Stop Fake News From Spreading On Facebook", BuzzFeed, retrieved 20 November 2016

- ^ Lewis Sanders IV (11 October 2016), "'Divide Europe': European lawmakers warn of Russian propaganda", Deutsche Welle, retrieved 24 November 2016

- Ben Gilbert (15 November 2016), "Fed up with fake news, Facebook users are solving the problem with a simple list", Business Insider, retrieved 16 November 2016,

Some of these sites are intended to look like real publications (there are false versions of major outlets like ABC and MSNBC) but share only fake news; others are straight-up propaganda created by foreign nations (Russia and Macedonia, among others).

- ^ Townsend, Tess (21 November 2016), "Meet the Romanian Trump Fan Behind a Major Fake News Site", Inc. magazine, ISSN 0162-8968, retrieved 23 November 2016

- ^ Maheshwari, Sapna (20 November 2016), "How Fake News Goes Viral", The New York Times, ISSN 0362-4331, retrieved 20 November 2016

- ^ Kurtz, Howard, "Fake news and the election: Why Facebook is polluting the media environment with garbage", Fox News, archived from the original on 18 November 2016, retrieved 18 November 2016

- ^ Christopher Woolf (16 November 2016), "Kids in Macedonia made up and circulated many false news stories in the US election", Public Radio International, retrieved 18 November 2016

- ^ Lewis Sanders IV (17 November 2016), "Fake news: Media's post-truth problem", Deutsche Welle, retrieved 24 November 2016

- ^ Surana, Kavitha (23 November 2016), "The EU Moves to Counter Russian Disinformation Campaign", Foreign Policy, ISSN 0015-7228

{{citation}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Andrew Weisburd and Clint Watts (6 August 2016), "Trolls for Trump - How Russia Dominates Your Twitter Feed to Promote Lies (And, Trump, Too)", The Daily Beast, retrieved 24 November 2016

- ^ MacFarquhar, Neil (29 August 2016), "A Powerful Russian Weapon: The Spread of False Stories", The New York Times, p. A1, retrieved 24 November 2016

- "EU Parliament Urges Fight Against Russia's 'Fake News'", Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, Agence France-Presse and Reuters, 23 November 2016, retrieved 24 November 2016

- ^ "Concern over barrage of fake Russian news in Sweden", The Local, 27 July 2016, retrieved 25 November 2016

- Alyssa Newcomb (15 November 2016), "Facebook, Google Crack Down on Fake News Advertising", NBC News, NBC News, retrieved 16 November 2016

- ^ McAlone, Nathan (17 November 2016), "This fake-news writer says he makes over $10,000 a month, and he thinks he helped get Trump elected", Business Insider, retrieved 18 November 2016

- ^ THR staff (17 November 2016), "Facebook Fake News Writer Reveals How He Tricked Trump Supporters and Possibly Influenced Election", The Hollywood Reporter, retrieved 18 November 2016

- ^ Goist, Robin (17 November 2016), "The fake news of Facebook", The Plain Dealer, retrieved 18 November 2016

- President Barack Obama (7 November 2016), Remarks by the President at Hillary for America Rally in Ann Arbor, Michigan, White House Office of the Press Secretary, retrieved 16 November 2016

- Gardiner Harris and Melissa Eddy (17 November 2016), "Obama, With Angela Merkel in Berlin, Assails Spread of Fake News", The New York Times, retrieved 18 November 2016

- ^ Paul Mozur and Mark Scott (17 November 2016), "Fake News on Facebook? In Foreign Elections, That's Not New", The New York Times, retrieved 18 November 2016

- ^ "Merkel warns against fake news driving populist gains", Yahoo! News, Agence France-Presse, 23 November 2016, retrieved 23 November 2016

- Sonam Sheth (14 November 2016), "Google looking into grossly inaccurate top news search result displayed as final popular-vote tally", Business Insider, retrieved 16 November 2016

- "Google to ban fake news sites from its advertising network", Los Angeles Times, Associated Press, 14 November 2016, retrieved 16 November 2016

- "Google cracks down on fake news sites", The Straits Times, 15 November 2016, retrieved 16 November 2016

- ^ Richard Waters (15 November 2016), "Facebook and Google to restrict ads on fake news sites", Financial Times, retrieved 16 November 2016

- ^ Ohlheiser, Abby (19 November 2016), "Mark Zuckerberg outlines Facebook's ideas to battle fake news", The Washington Post, retrieved 19 November 2016

- ^ Vladimirov, Nikita (19 November 2016), "Zuckerberg outlines Facebook's plan to fight fake news", The Hill, ISSN 1521-1568, retrieved 19 November 2016

- ^ Frenkel, Sheera (14 November 2016), "Renegade Facebook Employees Form Task Force To Battle Fake News", BuzzFeed, retrieved 18 November 2016

- Shahani, Aarti (15 November 2016), "Facebook, Google Take Steps To Confront Fake News", National Public Radio, retrieved 20 November 2016

- ^ Cooke, Kristina (15 November 2016), "Google, Facebook move to restrict ads on fake news sites", Reuters, retrieved 20 November 2016

- "Facebook's Fake News Problem: What's Its Responsibility?", The New York Times, Associated Press, 15 November 2016, retrieved 20 November 2016

- ^ Mike Isaac (19 November 2016), "Facebook Considering Ways to Combat Fake News, Mark Zuckerberg Says", The New York Times, retrieved 19 November 2016

- ^ Samuel Burke (19 November 2016), "Zuckerberg: Facebook will develop tools to fight fake news", CNNMoney, CNN, retrieved 19 November 2016

- ^ Chappell, Bill (19 November 2016), "'Misinformation' On Facebook: Zuckerberg Lists Ways Of Fighting Fake News", National Public Radio, retrieved 19 November 2016

- ^ Stelter, Brian (7 November 2016), "How Donald Trump made fact-checking great again", CNNMoney, CNN, retrieved 19 November 2016

- ^ Kessler, Glenn (10 November 2016), "Fact checking in the aftermath of a historic election", The Washington Post, retrieved 19 November 2016

- ^ Neidig, Harper (17 November 2016), "Fact-checkers call on Zuckerberg to address spread of fake news", The Hill, ISSN 1521-1568, retrieved 19 November 2016

- Hartlaub, Peter (24 October 2004), "Web sites help gauge the veracity of claims / Online resources check ads, rumors", San Francisco Chronicle, p. A1, retrieved 25 November 2016

- "Fact-Checking Deceptive Claims About the Federal Health Care Legislation - by Staff, FactCheck.org". 2010 Sigma Delta Chi Award Honorees. Society of Professional Journalists. Retrieved 25 November 2016.

- ^ Columbia University (2009), "National Reporting - Staff of St. Petersburg Times", 2009 Pulitzer Prize Winners, retrieved 24 November 2016,

For "PolitiFact," its fact-checking initiative during the 2008 presidential campaign that used probing reporters and the power of the World Wide Web to examine more than 750 political claims, separating rhetoric from truth to enlighten voters.

- ^ Novak, Viveca (10 April 2009), "Ask FactCheck - Snopes.com", FactCheck.org, retrieved 25 November 2016

- McNamara, Paul (13 April 2009), "Fact-checking the fact-checkers: Snopes.com gets an 'A'", Network World, retrieved 25 November 2016

- ^ Lori Robertson and Eugene Kiely (18 November 2016), "How to Spot Fake News", FactCheck.org, retrieved 19 November 2016

- ^ Sharockman, Aaron (16 November 2016), "Let's fight back against fake news", PolitiFact.com, retrieved 19 November 2016

- ^ The International Fact-Checking Network (17 November 2016), "An open letter to Mark Zuckerberg from the world's fact-checkers", Poynter Institute, retrieved 19 November 2016

- ^ Hare, Kristen (September 21, 2015), Poynter names director and editor for new International Fact-Checking Network, Poynter Institute for Media Studies, retrieved 20 November 2016

- ^ About the International Fact-Checking Network, Poynter Institute for Media Studies, 2016, retrieved 20 November 2016

- "Google, Facebook move to curb ads on fake news sites", Kuwait Times, Reuters, 15 November 2016, retrieved 16 November 2016

- ^ Cassandra Jaramillo (15 November 2016), "How to break it to your friends and family that they're sharing fake news", The Dallas Morning News, retrieved 16 November 2016

- ^ Domonoske, Camila (23 November 2016), "Students Have 'Dismaying' Inability To Tell Fake News From Real, Study Finds", National Public Radio, retrieved 25 November 2016

- ^ McEvers, Kelly (22 November 2016), "Stanford Study Finds Most Students Vulnerable To Fake News", National Public Radio, retrieved 25 November 2016

- ^ "Samantha Bee Interviews Russian Trolls, Asks Them About 'Subverting Democracy'", The Hollywood Reporter, 1 November 2016, retrieved 25 November 2016

- ^ Holub, Christian (1 November 2016), "Samantha Bee interviews actual Russian trolls", Entertainment Weekly, retrieved 25 November 2016

- ^ Wilstein, Matt (7 November 2016), "How Samantha Bee's 'Full Frontal' Tracked Down Russia's Pro-Trump Trolls", The Daily Beast, retrieved 25 November 2016

- Rogers, James (11 November 2016), "Facebook's 'fake news' highlights need for social media revamp, experts say", Fox News, retrieved 20 November 2016

- ^ Brian Feldman (15 November 2016), "Here's a Chrome Extension That Will Flag Fake-News Sites for You", New York Magazine, retrieved 16 November 2016

- "'I write fake news that gets shared on Facebook'", BBC News, BBC, 15 November 2016, retrieved 16 November 2016

- Will Oremus (15 November 2016), "The Real Problem Behind the Fake News", Slate magazine, retrieved 16 November 2016

Further reading

- Jamie Condliffe (15 November 2016), "Facebook's Fake-News Ad Ban Is Not Enough", MIT Technology Review, retrieved 16 November 2016

- Cassandra Jaramillo (15 November 2016), "How to break it to your friends and family that they're sharing fake news", The Dallas Morning News, retrieved 16 November 2016

- Craig Silverman and Lawrence Alexander (3 November 2016), "How Teens In The Balkans Are Duping Trump Supporters With Fake News", BuzzFeed, retrieved 16 November 2016

- Ishmael N. Daro and Craig Silverman (15 November 2016), "Fake News Sites Are Not Terribly Worried About Google Kicking Them Off AdSense", BuzzFeed, retrieved 16 November 2016

- Craig Silverman (16 November 2016), "Viral Fake Election News Outperformed Real News On Facebook In Final Months Of The US Election", BuzzFeed, retrieved 16 November 2016

- Timberg, Craig (24 November 2016), "Russian propaganda effort helped spread 'fake news' during election, experts say", The Washington Post, retrieved 25 November 2016

External links

- Kim LaCapria (2 November 2016), "Snopes' Field Guide to Fake News Sites and Hoax Purveyors", Snopes.com, snopes.com, retrieved 16 November 2016

- Rachel Dicker (14 November 2016), "Avoid These Fake News Sites at All Costs", U.S. News & World Report, retrieved 16 November 2016

- Lori Robertson and Eugene Kiely (18 November 2016), "How to Spot Fake News", FactCheck.org, Annenberg Public Policy Center, retrieved 19 November 2016

- Jared Keller (19 November 2016), "This Critique of Fake Election News Is a Must-Read for All Democracy Lovers", Mother Jones, retrieved 19 November 2016

- Lance Ulanoff (18 November 2016), "7 signs the news you're sharing is fake", Mashable, retrieved 19 November 2016

- Laura Hautala (19 November 2016), "How to avoid getting conned by fake news sites - Here's how you can identify and avoid sites that just want to serve up ads next to outright falsehoods.", CNET, retrieved 19 November 2016