This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Masem (talk | contribs) at 22:23, 30 January 2017 (→Reception: good quote here...). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 22:23, 30 January 2017 by Masem (talk | contribs) (→Reception: good quote here...)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) This article is about the original Pac-Man arcade game from 1980. For the video game series, see List of Pac-Man video games. For the video game character, see Pac-Man (character). For other uses, see Pac-Man (disambiguation).1980 video game

| Pac-Man / パックマン | |

|---|---|

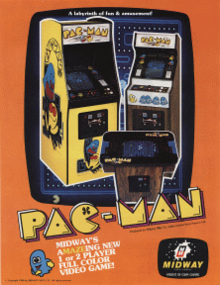

North American flyer North American flyer | |

| Developer(s) | Namco |

| Publisher(s) | |

| Designer(s) | Toru Iwatani |

| Programmer(s) | Shigeo Funaki |

| Composer(s) | Toshio Kai |

| Series | Pac-Man |

| Platform(s) | Arcade, Various |

| Release | |

| Genre(s) | Maze |

| Mode(s) | Single-player |

| Arcade system | Namco Pac-Man |

Pac-Man (Japanese: パックマン, Hepburn: Pakkuman), stylized as PAC-MAN, is an arcade game developed by Namco and first released in Japan in May 1980. It was created by Japanese video game designer Toru Iwatani. It was licensed for distribution in the United States by Midway and released in October 1980. Immensely popular from its original release to the present day, Pac-Man is considered one of the classics of the medium, and an icon of 1980s popular culture. Upon its release, the game—and, subsequently, Pac-Man derivatives—became a social phenomenon that yielded high sales of merchandise and inspired a legacy in other media, such as the Pac-Man animated television series and the top-ten hit single "Pac-Man Fever". Pac-Man was popular in the 1980s and 1990s and is still played in the 2010s.

When Pac-Man was released, the most popular arcade video games were space shooters, in particular, Space Invaders and Asteroids. The most visible minority were sports games that were mostly derivatives of Pong. Pac-Man succeeded by creating a new genre. Pac-Man is often credited with being a landmark in video game history and is among the most famous arcade games of all time. It is also one of the highest-grossing video games of all time, having generated more than $2.5 billion in quarters by the 1990s.

The character has appeared in more than 30 officially licensed game spin-offs, as well as in numerous unauthorized clones and bootlegs. According to the Davie-Brown Index, Pac-Man has the highest brand awareness of any video game character among American consumers, recognized by 94 percent of them. Pac-Man is one of the longest running video game franchises from the golden age of video arcade games. It is part of the collection of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. and New York's Museum of Modern Art.

Gameplay

The player controls Pac-Man through a maze, eating pac-dots (also called biscuits or just dots). When all pac-dots are eaten, Pac-Man is taken to the next stage. Between some stages, one of three intermission animations plays. Four enemies (Blinky, Pinky, Inky and Clyde) roam the maze, trying to catch Pac-Man. If an enemy touches Pac-Man, he loses a life. Whenever Pac-Man occupies the same tile as an enemy, he is considered to have collided with that ghost. When all lives have been lost, the game ends. Pac-Man is awarded a single bonus life at 10,000 points by default—DIP switches inside the machine can change the required points or disable the bonus life altogether.

Near the corners of the maze are four larger, flashing dots known as Power Pellets that provide Pac-Man with the temporary ability to eat the enemies. The enemies turn deep blue, reverse direction and usually move more slowly. When an enemy is eaten, its eyes remain and return to the center box where it is regenerated in its normal color. Blue enemies flash white to signal that they are about to become dangerous again and the length of time for which the enemies remain vulnerable varies from one stage to the next, generally becoming shorter as the game progresses. In later stages, the enemies go straight to flashing, bypassing blue, which means that they can only be eaten for a short amount of time, although they still reverse direction when a power pellet is eaten; in even later stages, the ghosts do not become edible (i.e., they do not change color and still make Pac-Man lose a life on contact), but they still reverse direction.

Enemies

Main article: Ghosts (Pac-Man)The enemies in Pac-Man are known variously as "monsters" and "ghosts". Despite the seemingly random nature of the enemies, their movements are strictly deterministic, which players have used to their advantage. In an interview, creator Toru Iwatani stated that he had designed each enemy with its own distinct personality in order to keep the game from becoming impossibly difficult or boring to play. More recently, Iwatani described the enemy behaviors in more detail at the 2011 Game Developers Conference. He stated that the red enemy chases Pac-Man, and the pink and blue enemies try to position themselves in front of Pac-Man's mouth. Although he claimed that the orange enemy's behavior is random, a careful analysis of the game's code reveals that it actually chases Pac-Man most of the time, but also moves toward the lower-left corner of the maze when it gets too close to Pac-Man.

Although Midway's 1980 flyer for Pac-Man used both the terms "monsters" and "ghost monsters", the term "ghosts" started to become more popular after technical limitations in the Atari 2600 version caused the antagonists to flicker and seem ghostlike, leading them to be referred to in the manual as "ghosts", and they have most frequently been referred to as ghosts in English ever since.

| This article may need to be rewritten to comply with Misplaced Pages's quality standards. You can help. The talk page may contain suggestions. (July 2023) |

| Ghosts | |

|---|---|

| Pac-Man characters | |

The original 1980 Pac-Man title screen featuring the four primary ghosts alongside their respective names. Below is how they all appear when they become edible within the game. The original 1980 Pac-Man title screen featuring the four primary ghosts alongside their respective names. Below is how they all appear when they become edible within the game. | |

| First game | Pac-Man (1980) |

| Created by | Toru Iwatani |

| Voiced by |

Blinky

|

| In-universe information | |

| Species | Ghost |

Blinky, Pinky, Inky and Clyde, collectively known as the Ghost Gang, are a quartet of colorful ghost characters from the Pac-Man video game franchise. Created by Toru Iwatani, they first appear in the 1980 arcade game Pac-Man as the sole antagonists. The ghosts have appeared in every Pac-Man game since, sometimes becoming minor antagonists or allies to Pac-Man, such as in Pac-Man World and the Pac-Man and the Ghostly Adventures animated series.

Some entries in the series went on to add other ghosts to the group, such as Sue in Ms. Pac-Man, Tim in Jr. Pac-Man, and Funky and Spunky in Pac-Mania; however, these did not appear in most later games. The group has since gained a positive reception and is cited as one of the most recognizable video game villains of all time.

Concept and creation

The ghosts were created by Toru Iwatani, who was the head designer for the original Pac-Man arcade game. The idea for the ghosts was made from Iwatani's desire to create a video game that could attract women and younger players, particularly couples, at a time where most video games were "war"-type games or Space Invaders clones. In turn, he made the in-game characters cute and colorful, a trait borrowed from Iwatani's previous game Cutie Q (1979), which featured similar "kawaii" characters. Iwatani cited Casper the Friendly Ghost or Little Ghost Q-Taro as inspiration for the ghosts. Their simplistic design was also attributed to the limitations of the hardware at the time, only being able to display a certain amount of colors for a sprite. To prevent the game from becoming impossibly difficult or too boring to play, each of the ghosts were programmed to have their own distinct traits — the red ghost would directly chase Pac-Man, the pink and blue ghosts would position themselves in front of him, and the orange ghost would be random.

Originally, all four of the ghosts were meant to be red instead of multicolored, as ordered by Namco president Masaya Nakamura — Iwatani was against the idea, as he wanted the ghosts to be distinguishable from one another. Although he was admittedly afraid of Nakamura, he conducted a survey with his colleagues that asked if they wanted single-colored enemies or multicolored enemies. After being present with a 40-to-0 result in favor of multicolored ghosts, Nakamura agreed to the decision. The original Japanese version of the game had the ghosts named "Oikake", "Machibuse", "Kimagure" and "Otoboke", translating respectively to "chaser", "ambusher", "fickle" and "stupid". When the game was exported to the United States, Midway Games changed their names to "Shadow", "Speedy", "Bashful" and "Pokey", their nicknames being changed to "Blinky", "Pinky", "Inky" and "Clyde" respectively. Early promotional material would sometimes refer to the ghosts as "monsters" or "goblins".

Uproxx argues that the ghost are really just people in costumes, based on what is revealed between rounds in the game. A cutscene that appears after the 5th round of the game, shows the ghost Blinky chasing after Pac-Man, and their ghost costume snags on a nail and rips, revealing a leg underneath. In a later cutscene, they have a rip in their ghost costume, then after going off screen, they are seen back on the screen dragging the red costume behind them.

Cartoons

In the 1982 Pac-Man cartoon, the hero faced five Ghosts — four males wearing various styles of hats, and a female ghost named Sue, who wore earrings. The Ghost Monsters work for Mezmaron, who assigns them the job of finding the Power Pellet Forest.

The battle of Pac-Man vs. Ghost Monsters would have to address the issue of the original arcade game's 'cannibalism' somewhere along the line; after all, the basic appeal of Pac-Man was the indiscriminate ingestion of his foes. This was handled with such nonviolent dexterity that Hanna-Barbera could have written a textbook for Action for Children's Television on the subject. Pac-Man only chomped the Ghost Monsters when defending his loved ones or the Power Forest (as opposed to the videogame, where the lead character was on the offensive), and once chomped, the Ghost Monsters merely disappeared temporarily, re-emerging unscathed after picking up new shrouds from Mezmaron's wardrobe closet.

— Hal Erickson

The 2013 TV series Pac-Man and the Ghostly Adventures featured Pac-Man as a high-school student battling the ghost forces of Lord Betrayus. Blinky, Inky, Pinky and Clyde act as secret allies to Pac-Man, hoping to one day be restored to life in exchange.

Reception

The ghosts have received a positive reception from critics and have been cited as one of the most recognizable video game villains of all time. IGN commented on each of the ghosts having their own personality and "adorable" design. Boy's Life praised their simplicity and determination, labeling them as one of the most recognizable villains in video game history. In their list of the 50 "coolest" video game villains, Complex ranked the ghosts in as the fourth, noting of their iconic design and recognition and for being "pretty tough customers" Metro UK listed them at second place in their list of the ten greatest video game villains of all time, praising their easy recognition and cute designs.

Kotaku stated that the ghosts' artificial intelligence was still impressive by modern standards, being "smarter than you think". GamesRadar+ liked each of the ghosts having their own unique AI and traits, while GameSpy said that the ghosts' intelligence is one of the game's "most endearing" aspects for adding a new layer of strategy to the game.

Inky alone was ranked the seventh greatest game villain of all time by Guinness World Records in 2013, based on reader votes.

References

- Date shown in January 1982 article "Midway celebrates Pac-Man".

- ^ Namco Bandai Games Inc. (June 2, 2005). "Bandai Namco press release for 25th Anniversary Edition" (in Japanese). bandainamcogames.co.jp/. Archived from the original on December 30, 2007. Retrieved October 10, 2007.

2005年5月22日で生誕25周年を迎えた『パックマン』。 ("Pac-Man celebrates his 25th anniversary on May 22, 2005", seen in image caption)

- ^ Long, Tony (October 10, 2007). "Oct. 10, 1979: Pac-Man Brings Gaming Into Pleistocene Era". Wired. Archived from the original on September 11, 2014. Retrieved October 10, 2007.

puts the date at May 22, 1980 and is planning an official 25th anniversary celebration next year.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - "Game Board Schematic". Midway Pac-Man Parts and Operating Manual (PDF). Chicago, Illinois: Midway Games. December 1980. Retrieved July 20, 2009.

- Nitsche, Michael (March 31, 2009). "Games and Rules". Video Game Spaces: Image, Play, and Structure in 3D Worlds. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. p. 26. ISBN 0-262-14101-9.

they would not realize the fundamental logical difference between a version of Pac-Man (Iwatani 1980) running on the original Z80

- "Pac-Man still going strong at 30". UPI.com. May 22, 2010. Retrieved May 22, 2012.

- "Oct. 10, 1979: Pac-Man Brings Gaming Into Pleistocene Era". Wired. October 10, 2007.

- "Pac 'n Roll Review". GameSpot.com. August 23, 2005. Retrieved May 22, 2012.

- Wolf, Mark J. P. (2008). "The video game explosion: A history from PONG to PlayStation and beyond". ISBN 978-0-313-33868-7.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Green, Chris (June 17, 2002). "Pac-Man". Salon.com. Retrieved February 12, 2006.

- "Pac-Man Fever". Time Magazine. April 5, 1982. Archived from the original on January 22, 2011. Retrieved October 15, 2009.

Columbia Records' Pac-Man Fever ... was No. 9 on the Billboard Hot 100 last week.

- Goldberg, Marty (January 31, 2002). "Pac-Man: The Phenomenon: Part 1". Arcadegaming.us. Archived from the original on October 16, 2007. Retrieved July 31, 2006.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Parish, Jeremy (2004). "The Essential 50: Part 10 – Pac Man". 1UP.com. Retrieved July 31, 2006.

- Steve L. Kent (2001). The ultimate history of video games: from Pong to Pokémon and beyond : the story behind the craze that touched our lives and changed the world. Prima. p. 143. ISBN 0-7615-3643-4. Retrieved May 1, 2011.

Despite the success of his game, Iwatani never received much attention. Rumors emerged that the unknown creator of Pac-Man had left the industry when he received only a $3500 bonus for creating the highest-grossing video game of all time.

- Cite error: The named reference

Wolf-73was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - Chris Morris (May 10, 2005). "Pac Man turns 25: A pizza dinner yields a cultural phenomenon – and millions of dollars in quarters". CNN. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

In the late 1990s, Twin Galaxies, which tracks video game world record scores, visited used game auctions and counted how many times the average Pac Man machine had been played. Based on those findings and the total number of machines that were manufactured, the organization said it believed the game had been played more than 10 billion times in the 20th century.

- "The Legacy of Pac-Man". Archived from the original on January 21, 1998.

- "Pac Man Bootleg Board Information". Archived from the original on July 2, 2007.

- "Davie Brown Celebrity Index: Mario, Pac-Man Most Appealing Video Game Characters Among Consumers". PR Newswire. Archived from the original on June 27, 2009. Retrieved May 6, 2011.

- "History of Computing: Video games – Golden Age". Thocp.net. Retrieved May 22, 2012.

- Antonelli, Paola (November 29, 2012). "Video Games: 14 in the Collection, for Starters". MoMA. Retrieved November 30, 2012.

- "Pacman Game". Retrieved November 13, 2012.

- ^ Pac-Man, The Arcade Flyer Archive, 1980, archived from the original on November 30, 2013, retrieved May 23, 2012

- ^ "What is Pacman?". Pacman.com. Namco. Archived from the original on November 28, 2010. Retrieved November 3, 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) Cite error: The named reference "Pacman.com" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ Martijn Müller (June 3, 2010). "Pac-Man wereldrecord beklonken en het hele verhaal" (in Dutch). NG-Gamer. Archived from the original on February 27, 2012. Retrieved November 3, 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) Cite error: The named reference "nlgd" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - Mateas, Michael (2003). "Expressive AI: Games and Artificial Intelligence" (PDF). Proceedings of Level Up: Digital Games Research Conference, Utrecht, Netherlands.

- "News Headlines". Cnbc.com. March 3, 2011. Retrieved May 22, 2012.

- "pacmanmuseum.com - Nomenclature Conflicts". Retrieved November 4, 2015.

- ^ "Blinky Voices (Pac-Man)". Behind The Voice Actors. Retrieved March 7, 2023. A green check mark indicates that a role has been confirmed using a screenshot (or collage of screenshots) of a title's list of voice actors and their respective characters found in its credits or other reliable sources of information.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ "Inky Voices (Pac-Man)". Behind The Voice Actors. Retrieved March 7, 2023. A green check mark indicates that a role has been confirmed using a screenshot (or collage of screenshots) of a title's list of voice actors and their respective characters found in its credits or other reliable sources of information.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ "Pinky Voices (Pac-Man)". Behind The Voice Actors. Retrieved March 7, 2023. A green check mark indicates that a role has been confirmed using a screenshot (or collage of screenshots) of a title's list of voice actors and their respective characters found in its credits or other reliable sources of information.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ "Clyde Voices (Pac-Man)". Behind The Voice Actors. Retrieved March 7, 2023. A green check mark indicates that a role has been confirmed using a screenshot (or collage of screenshots) of a title's list of voice actors and their respective characters found in its credits or other reliable sources of information.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ Purchese, Robert (May 20, 2010). "Iwatani: Pac-Man was made for women". Eurogamer. Archived from the original on March 4, 2019. Retrieved August 19, 2019.

- Kohler, Chris (2005). Power-Up: How Japanese Video Games Gave the World an Extra Life. BradyGames. p. 51-52. ISBN 0-7440-0424-1. Retrieved July 16, 2019.

- Kohler, Chris. "Q&A: Pac-Man Creator Reflects on 30 Years of Dot-Eating | Game|Life". Wired. Wired.com. Retrieved July 23, 2012.

- ^ Mateas, Michael (2003). "Expressive AI: Games and Artificial Intelligence" (PDF). Proceedings of Level up: Digital Games Research Conference, Utrecht, Netherlands. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 14, 2012. Retrieved November 28, 2012.

- ^ England, Lucy (June 11, 2015). "When Pac-Man was invented there was a huge internal fight with the CEO over what colour the ghosts should be". Business Insider. Archived from the original on August 7, 2017. Retrieved August 19, 2019.

- ^ DeMaria, Rusel; Wilson, Johnny L. (December 18, 2003). High Score!: The Illustrated History of Electronic Games (2nd ed.). McGraw-Hill Osborne Media. ISBN 0-07-222428-2.

- Pac-Man, The Arcade Flyer Archive, 1980, archived from the original on August 10, 2007, retrieved May 23, 2012

- Birch, Nathan (May 22, 2015). "The Ghosts Are Just Guys Under Sheets? 12 Delectable Facts About Arcade Classic 'Pac-Man'". UPROXX. Retrieved May 14, 2024.

- Erickson, Hal (2005). Television Cartoon Shows: An Illustrated Encyclopedia, 1949 Through 2003 (2nd ed.). McFarland & Co. p. 601. ISBN 978-1476665993.

- Perlmutter, David (May 4, 2018). The Encyclopedia of American Animated Television Shows. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 443. ISBN 978-1-5381-0374-6.

- "Pac-Man Ghosts (Pinky, Blinky, etc.) is number 7". IGN. Archived from the original on July 19, 2010. Retrieved August 19, 2019.

- "The 5 Greatest Video Game Baddies of All-Time". Boy's Life. September 9, 2015. Archived from the original on April 9, 2017. Retrieved August 19, 2019.

- Kamer, Foster; Vincent, Brittany (November 1, 2012). "The 50 Coolest Video Game Villains of All Time". Complex. Archived from the original on May 8, 2018. Retrieved August 19, 2019.

- GameCentral (September 17, 2017). "10 best bad guys in video games". Metro UK. Archived from the original on August 11, 2019. Retrieved August 19, 2019.

- Grayson, Nathan (February 4, 2015). "Pac-Man Ghosts Are Smarter Than You Think". Kotaku. Archived from the original on March 19, 2017. Retrieved August 19, 2019.

- Kelly, Stephen (February 5, 2013). "Top 10 Videogame Bad Guys". GamesRadar+. Retrieved August 19, 2019.

- GameSpy Staff (February 25, 2011). "GameSpy's Top 50 Arcade Games of All-Time - Pac-Man". GameSpy. Archived from the original on February 9, 2019. Retrieved August 19, 2019.

- Nichols, Scott (January 24, 2013). "Guinness World Records counts down top 50 video game villains". Digital Spy. Retrieved August 19, 2019.

| Pac-Man | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Video games | |||||

| Other media | |||||

| Companies | |||||

| Characters | |||||

| Related |

| ||||

Kill screen

Pac-Man was designed to have no ending – as long as at least one life was left, the game should be able to go on indefinitely. However, a bug keeps this from happening: Normally, no more than seven fruit are displayed on the HUD at the bottom of the screen at any given time. But when the internal level counter, which is stored in a single byte, or eight bits, reaches 255, the subroutine that draws the fruit erroneously "rolls over" this number to zero when it is determining the number of fruit to draw, using fruit counter = internal level counter + 1. Normally, when the fruit counter is below eight, the drawing subroutine draws one fruit for each level, decrementing the fruit counter until it reaches zero. When the fruit counter has overflowed to zero, the first decrement sets the fruit counter back to 255, causing the subroutine to draw a total of 256 fruit instead of the maximum of seven.

This corrupts the bottom of the screen and the entire right half of the maze with seemingly random symbols and tiles, overwriting the values of edible dots which makes it impossible to eat enough dots to beat the level. Because this effectively ends the game, this "split-screen" level is often referred to as the "kill screen". There are 114 dots on the left half of the screen, nine dots on the right, and one bonus key, totaling 6,310 points. When all of the dots have been cleared, nothing happens. The game does not consider a level to be completed until 244 dots have been eaten. Each time a life is lost, the nine dots on the right half of the screen get reset and can be eaten again, resulting in an additional 90 points per extra man. In the best-case scenario (five extra men), 6,760 points will be the maximum score possible, but only 168 dots can be harvested, and that is not enough to change levels. Four of the nine dots on the right half of the screen are invisible, but can be heard when eaten. Some dots are invisible but the rest can be seen, although some are a different color from normal. One method for safely clearing this round is to trap the ghosts. To trap the three important ghosts, the player must begin by going right until Pac-man reaches a blue letter 'N', and then he goes down. He keeps going down until he reaches a blue letter 'F', and then he goes right. He keeps going right until he reaches a yellow 'B', and then he goes down again. When executed properly, Pac-Man will hit an invisible wall almost immediately after the last turn is made. Eventually, the red ghost will get stuck. The pink ghost follows a few seconds later. The blue ghost will continue to move freely for several moments until the next scatter mode occurs. At that point, it will try to reach some location near the right edge of the screen and get stuck with the pink and red ghost instead. The orange ghost is the only one still on the loose, but he is no real threat since he runs to his corner whenever Pac-Man gets close so that it is easy to eat all the dots. Emulators and code analysis have revealed what would happen if this 256th level is cleared: the fruit and intermissions would restart at level 1 conditions, but the enemies would retain their higher speed and invulnerability to power pellets from the higher stages.

Perfect play

A perfect Pac-Man game occurs when the player achieves the maximum possible score on the first 256 levels (by eating every possible dot, power pellet, fruit, and enemy) without losing a single life, and using all extra lives to score as many points as possible on Level 257.

The first person to achieve this score is Billy Mitchell of Hollywood, Florida, who performed the feat in about six hours. Since then, over 20 other players have attained the maximum score in increasingly faster times. As of 2016, the world record, according to Twin Galaxies, is held by David Race, who in 2013 attained the maximum possible score of 3,333,360 points in 3 hours, 28 minutes, and 49 seconds.

In December 1982, an eight-year-old boy, Jeffrey R. Yee, supposedly received a letter from U.S. President Ronald Reagan congratulating him on a worldwide record of 6,131,940 points, a score only possible if he had passed the unbeatable Split-Screen Level. In September 1983, Walter Day, chief scorekeeper at Twin Galaxies, took the US National Video Game Team on a tour of the East Coast to visit video game players who claimed they could get through the Split-Screen Level. No video game player could demonstrate this ability. In 1999, Billy Mitchell offered $100,000 to anyone who could pass through the Split-Screen Level before January 1, 2000. The prize was never claimed.

Development

Up into the early 1970s, Namco primarily specialized in kiddie rides for Japanese department stores. Masaya Nakamura, the founder of Namco, saw the potential value of video games, and started to direct the company toward arcade games, starting with electromechanical ones such as F-1 (1976). He later hired a number of software engineers to develop their own video games as to compete with companies like Atari, Inc..

Pac-Man was one of the first games developed by this new department within Namco. The game was developed primarily by a young employee named Toru Iwatani over the course of a year, beginning in April 1979, employing a nine-man team. It was based on the concept of eating, and the original Japanese title is Pakkuman (パックマン), inspired by the Japanese onomatopoeic phrase paku-paku taberu (パクパク食べる), where paku-paku describes (the sound of) the mouth movement when widely opened and then closed in succession.

Although Iwatani has repeatedly stated that the character's shape was inspired by a pizza missing a slice, he admitted in a 1986 interview that this was a half-truth and the character design also came from simplifying and rounding out the Japanese character for mouth, kuchi (口). Iwatani attempted to appeal to a wider audience—beyond the typical demographics of young boys and teenagers. His intention was to attract girls to arcades because he found there were very few games that were played by women at the time. This led him to add elements of a maze, as well as cute ghost-like enemy characters. Eating to gain power, Iwatani has said, was a concept he borrowed from Popeye. The result was a game he named Puck Man as a reference to the main character's hockey puck shape. Later in 1980, the game was picked up for manufacture in the United States by Bally division Midway, which changed the game's name from Puck Man to Pac-Man in an effort to avoid vandalism from people changing the letter 'P' into an 'F' to form the word fuck. The cabinet artwork was also changed and the pace and level of difficulty increased to appeal to western audiences.

Reception

When first launched in Japan by Namco in 1980, the game received a lukewarm response, as Space Invaders and other similar games were more popular at the time. However, Pac-Man's success in North America in the same year took competitors and distributors completely by surprise. Marketing executives who saw Pac-Man at a trade show prior to release completely overlooked the game (along with the now-classic Defender), while they looked to a racing car game called Rally-X as the game to outdo that year. The appeal of Pac-Man was such that the game caught on immediately with the public; it quickly became far more popular than anything seen in the game industry up to that point. Pac-Man outstripped Asteroids as the best-selling arcade game in North America, grossing over $1 billion in quarters within a year, by the end of 1980, surpassing the revenues grossed by the then highest-grossing film Star Wars. Nakamura said in a 1983 interview that though he did expect Pac-Man to be successful, "I never thought it would be this big".

More than 350,000 Pac-Man arcade cabinets were sold (retailing at around $2400 each) for $1 billion within 18 months of release (inflation adjusted: $2.4 billion in 2011). By 1982, the game had sold 400,000 arcade machines worldwide and an estimated 7 billion coins had been inserted into Pac-Man machines. In addition, United States revenues from Pac-Man licensed products (games, T-shirts, pop songs, wastepaper baskets, etc.) exceeded $1 billion (inflation adjusted: $2.33 billion in 2011). The game was estimated to have had 30 million active players across the United States in 1982.

Toward the end of the 20th century, the arcade game's total gross consumer revenue had been estimated by Twin Galaxies at more than 10 billion quarters ($2.5 billion), making it the highest-grossing video game of all time. In 2016, USgamer calculated that the machines' inflation-adjusted takings were equivalent to $7.68 billion. In January 1982, the game won the overall Best Commercial Arcade Game award at the 1981 Arcade Awards. In 2001, Pac-Man was voted the greatest video game of all time by a Dixons poll in the UK. The readers of Killer List of Videogames name Pac-Man as the No. 1 video game on its "Top 10 Most Popular Video games" list, the staff name it as No. 18 on its "Top 100 Video Games" list, and Ms. Pac-Man is given similar recognition.

Impact

The game is regarded as one of the most influential video games of all time, for a number of reasons: its titular character was the first original gaming mascot, the game established the maze chase game genre, it demonstrated the potential of characters in video games, it opened gaming to female audiences, and it was gaming's first licensing success. In addition, it was the first video game to feature power-ups, and it is frequently credited as the first game to feature cut scenes, in the form of brief comical interludes about Pac-Man and Blinky chasing each other around during those interludes, though Space Invaders Part II employed a similar technique that same year. Pac-Man is also credited for laying the foundations for the stealth game genre, as it emphasized avoiding enemies rather than fighting them, and had an influence on the early stealth game Metal Gear, where guards chase Solid Snake in a similar manner to Pac-Man when he is spotted.

Legacy

Pac-Man has also influenced many other games, ranging from the sandbox game Grand Theft Auto (where the player runs over pedestrians and gets chased by police in a similar manner) to early first-person shooters such as MIDI Maze (which had similar maze-based gameplay and character designs). Game designer John Romero credited Pac-Man as the game that had the biggest influence on his career; Wolfenstein 3D was similar in level design and featured a Pac-Man level from a first-person perspective, while Doom had a similar emphasis on mazes, power-ups, killing monsters, and reaching the next level. Pac-Man also influenced the use of power-ups in later games such as Arkanoid.

Remakes and sequels

See also: List of Pac-Man video games and List of Pac-Man clonesPac-Man is one of the few games to have been consistently published for over three decades, having been remade on numerous platforms and spawned many sequels. Re-releases include ported and updated versions of the original arcade game. Numerous unauthorized Pac-Man clones appeared soon after its release. The combined sales of counterfeit arcade machines sold nearly as many units as the original Pac-Man, which had sold more than 300,000 machines.

One of the first ports to be released was the much-maligned port for the Atari 2600, which only somewhat resembles the original and was widely criticized for its flickering ghosts, due to the 2600's limited memory and hardware compared to the arcade machine. Despite the criticism, this version of Pac-Man sold seven million units at $37.95 per copy, and became the best-selling game of all time on the Atari 2600 console. While enjoying initial sales success, Atari had overestimated demand by producing 12 million cartridges, of which 5 million went unsold. The port's poor quality damaged the company's reputation among consumers and retailers, which would eventually become one of the contributing factors to Atari's decline and the North American video game crash of 1983, alongside Atari's E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial.

Meanwhile, Coleco's tabletop Mini-Arcade versions of the game yielded 1.5 million units sold in 1982.

II Computing listed it tenth on the magazine's list of top Apple II series games as of late 1985, based on sales and market-share data, and in December 1987 alone Mindscape's IBM PC version of Pac-Man sold over 100,000 copies. The game was also released for Atari's 5200 and 8-bit computers, Intellivision, the Commodore 64 and VIC-20, and the Nintendo Entertainment System. For handheld game consoles, it was released on the Game Boy, Sega Game Gear, Game Boy Color, and the Neo Geo Pocket Color.

Pac-Man has been featured in Namco's long-running Namco Museum video game compilations. Downloads of the game have been made available on game services such as Xbox Live Arcade, GameTap, and Virtual Console. Namco has released mobile versions of BREW, Java, and iOS, as well as Palm PDAs and Windows Mobile-based devices. A port of Pac-Man for Android can be controlled not only through an Android phone's trackball but through touch gestures or its on-board accelerometer. As of 2010, Namco had sold more than 30 million paid downloads of Pac-Man on BREW in the United States alone.

Microsoft released Microsoft Return of Arcade in 1996 and Microsoft Return of Arcade: Anniversary Edition in 2000, and includes Pac-Man as one of its bundled arcade games.

Namco has repeatedly re-released the game to arcades. In 2001, Namco released a Ms. Pac-Man/Galaga "Class of 1981 Reunion Edition" cabinet with Pac-Man available for play as a hidden game. To commemorate Pac-Man's 25th anniversary in 2005, Namco released a revision that officially featured all three games.

Namco Networks sold a downloadable Windows PC version of Pac-Man in 2009 which also includes an "Enhanced" mode which replaces all of the original sprites with the sprites from Pac-Man Championship Edition. Namco Networks made a downloadable bundle which includes their PC version of Pac-Man and their port of Dig Dug called Namco All-Stars: Pac-Man and Dig Dug.

In 2010, Namco Bandai announced the release of the game on Windows Phone 7 as an Xbox Live game.

Pac-Man has numerous sequels and spin-offs, including only one of which was designed by Tōru Iwatani. Some of the follow-ups were not developed by Namco either —including the most significant, Ms. Pac-Man, released in the United States in 1981. Originally called Crazy Otto, this unauthorized hack of Pac-Man was created by General Computer Corporation and sold to Midway without Namco's permission. The game features several changes from the original Pac-Man, including faster gameplay, more mazes, new intermissions, and moving bonus items. Some consider Ms. Pac-Man to be superior to the original or even the best in the entire series. Stan Jarocki of Midway stated that Ms. Pac-Man was conceived in response to the original Pac-Man being "the first commercial video game to involve large numbers of women as players" and that it is "our way of thanking all those lady arcaders who have played and enjoyed Pac-Man." Namco sued Midway for exceeding their license. Eventually, Bally Midway struck a deal with Namco to officially license Ms. Pac-Man as a sequel. Namco today officially owns Ms. Pac-Man in its other releases.

Following Ms. Pac-Man, Bally Midway released several other unauthorized spin-offs, such as Pac-Man Plus, Jr. Pac-Man, Baby Pac-Man and Professor Pac-Man, resulting in Namco severing business relations with Midway.

Various platform games based on the series have also been released by Namco, such as 1984's Pac-Land and the Pac-Man World series, which features Pac-Man in a 3-D world. More modern versions of the original game have also been developed, such as the multiplayer Pac-Man Vs. for the Nintendo GameCube.

On June 5, 2007, the first Pac-Man World Championship was held in New York City, which brought together ten competitors from eight countries to play the new Pac-Man Championship Edition developed by Tōru Iwatani. Its sequel was released November 2010.

For the weekend of May 21–23, 2010, Google changed the Google logo on its homepage to a Google Doodle of a fully playable version of the game in recognition of the 30th anniversary of the game's release. The game featured the ability to play both Pac-Man and Ms. Pac-Man simultaneously. After finishing the game, the website automatically redirected the user to a search of Pac-Man 30th Anniversary. Companies across the world experienced slight drops in productivity due to the game, estimated to be valued at the time as $120,000,000 (approximately €95,400,000; £83,000,000). However, The Official ASTD Blog noted that the total loss, "spread out across the entire world isn't a huge loss, comparatively speaking". In total, the game devoured around 4.8 million hours of work productivity that day. Some organizations even temporarily blocked Google's website from workplace computers the Friday it was uploaded, particularly where it violated regulations against recreational games. Because of the popularity of the Pac-Man doodle, Google later allowed access to the game through a separate web page. On March 31, 2015, Google Maps added an option allowing a Pac-Man style game to be played using streets on the map as the maze.

In 2011, Namco sent a DMCA notice to the team that made the programming language Scratch saying that a programmer had infringed copyright by making a Pac-Man game using the language and uploading it to Scratch's official website.

In April 2011, Soap Creative published World's Biggest Pac-Man working together with Microsoft and Namco-Bandai to celebrate Pac-Man's 30th anniversary. It is a multiplayer browser-based game with user-created, interlocking mazes.

In 2016 an in-app version of Pac-Man was introduced in Facebook Messenger. This allows users to play the game against their friends while talking over Facebook.

Non-video game versions

In 1982, Milton Bradley released a board game based on Pac-Man. In this game, players move up to four Pac-Man characters (traditional yellow plus red, green and blue) plus two ghosts as per the throws of a pair of dice. Each Pac-Man is assigned to a player while the ghosts are neutral and controlled by all players. Each player moves their Pac-Man the number of spaces on either die and a ghost the number of spaces on the other die, the Pac-Man consuming any white marbles (the equivalent of dots) and yellow marbles (the equivalent of power pellets) in its path. Players can move a ghost onto a Pac-Man and claim two white marbles from its player. They can also move a Pac-Man with a yellow marble inside it onto a ghost and claim two white marbles from any other player (following which the yellow marble is placed back in the maze. The game ends when all white marbles have been cleared from the board and the player with the largest number of white marbles is then declared the winner.

Sticker manufacturer Fleer included Pac-Man Rub Off Game cards with their Pac-Man stickers. The card packages contain a Pac-Man style maze with all points along the path covered with opaque coverings. Starting from the lower board Pac-Man starting position, the player moves around the maze while scratching off the coverings to score points. A white dot scores one point, a blue monster scores ten points, and a cherry scores 50 points. Uncovering a red, orange, or pink monster scores no points but the game ends when a third such monster is uncovered. A Ms. Pac-Man version of the game also includes pretzels (100 points) and bananas (200 points).

Nelsonic Industries produced a Pac-Man LCD wristwatch game. This follows essentially the same rules as the video version, though with a simplified maze.

A pinball version titled Mr. & Mrs. Pac-Man was designed by George Christian and released by Bally/Midway in 1982. The spin-off arcade game Baby Pac Man also contains a non-video pinball element.

In popular culture

The Pac-Man character and game series became an icon of video game culture during the 1980s, and a wide variety of Pac-Man merchandise has been marketed with the character's image, from t-shirts and toys to hand-held video game imitations and even specially shaped pasta. The Pac-Man animated TV series produced by Hanna–Barbera aired on ABC from 1982 to 1983. At one time, a feature film based on the game was also in development. In 2010, a computer-generated animated series titled Pac-Man and the Ghostly Adventures was reported to be in the works. The show was released on Disney XD in June 2013. Pac-Man has also been referenced in the 2010 film Scott Pilgrim vs. the World, where the game's origins as Puck-Man is mentioned several times. Clyde appears in the Disney computer-animated film Wreck-It Ralph as one of the several villains participating in a group therapy session, voiced by Kevin Deters. His cohorts, Inky, Blinky, and Pinky, appear together in Game Central Station for a few scenes, and Pac-Man makes a cameo appearance during the Fix-It Felix Jr. 30th Anniversary party. General Mills manufactured a cereal by the Pac-Man name in 1983. Over the cereal's lifespan, characters from sequels Super Pac-Man and Ms. Pac-Man were also added.

Guinness World Records has awarded the Pac-Man series eight records in Guinness World Records: Gamer's Edition 2008, including First Perfect Pac-Man Game for Billy Mitchell's July 3, 1999 score and "Most Successful Coin-Operated Game". On June 3, 2010, at the NLGD Festival of Games, the game's creator Toru Iwatani officially received the certificate from Guinness World Records for Pac-Man having had the most "coin-operated arcade machines" installed worldwide: 293,822. The record was set and recognized in 2005 and mentioned in the Guinness World Records: Gamer's Edition 2008, but finally actually awarded in 2010.

Pac-Man has been referenced in numerous other media. In music, the Buckner & Garcia song "Pac-Man Fever" (1981) went to No. 9 on the Billboard Hot 100 charts, and received a Gold certification with over a million records sold by 1982, and a total of 2.5 million copies sold as of 2008. Their Pac-Man Fever album (1982) also received a Gold certification for selling over a million records. "Weird Al" Yankovic recorded a demo song in 1981 titled "Pac-Man" that is a parody of "Taxman" by The Beatles. Jonzun Crew's "Pack Jam" (1983) was inspired by Michael Jonzun's distaste towards the popular Pac-Man game. Hip hop emcee Lil' Flip sampled sounds from the game Pac-Man and Ms. Pac-Man to make his top-20 single "Game Over" (2004). Namco America filed a lawsuit against Sony Music Entertainment for unauthorized use of these samples. The suit was eventually settled out of court. Aphex Twin released an EP dedicated to the game, Pac-Man EP, in 1992.

Ken Uston's strategy guide Mastering Pac-Man yielded 750,000 copies sold, reaching No. 5 on B. Dalton's mass-market bestseller list. By 1983, 1.7 million copies of Mastering Pac-Man had been printed. In comedy, there is a popular Pac-Man joke on the controversy regarding the influence of video games on children, stating "If Pacman had affected us as kids we'd be running around in dark rooms, munching pills and listening to repetitive music."

The game has inspired various real-life recreations, involving either real people or robots. One event called Pac-Manhattan set a Guinness World Record for "Largest Pac-Man Game" in 2004. The business term "Pac-Man defense" in mergers and acquisitions refers to a hostile takeover target that attempts to reverse the situation and take over its would-be acquirer instead, a reference to Pac-Man's power pellets. The game's popularity has led to "Pac-Man" being adopted as a nickname, most notably by boxer Manny Pacquiao, as well as the American football player Adam Jones.

Pac-Man has found its position beyond the game world. Under a National Science Foundation funded project, the computer science department at UC Berkeley has developed a custom version of Pac-Man in Python to teach students basic Artificial Intelligence concepts, such as informed state-space search, probabilistic inference, and reinforcement learning. Students are asked to complete a series of problems from simple to difficult, to eventually design a Pac-Man agent that automatically eats all the Pac-dots on the map. The concepts learned during these problems underlie many real-world AI application areas, such as natural language processing, computer vision, and robotics.

In January 2013, Pac-Man and Blinky appeared on the top Massachusetts Institute of Technology's Great Dome as part of a traditional hack or prank used to demonstrate the technical aptitude and cleverness of the students. According to the MIT alumni blog, Slice of MIT, the Pac-Man, Blinky battle was intended to serve as a metaphor for the semester. "Pac-Man represents the unquenchable search for knowledge, while Blinky represents the unforeseen distractions that may occur.”

On June 10, 2014, Pac-Man was confirmed to appear as a playable character in the game Super Smash Bros. for Nintendo 3DS and Wii U. The 3DS version also has a stage based on the original arcade game, called Pac-Maze. A Pac-Man amiibo figurine was also released by Nintendo on May 29, 2015.

On February 1, 2015, as part of the Super Bowl, a Bud Light commercial featured a real-life Pac-Man board with one of the players as Pac-Man and using computer graphic ghosts.

The Pac-Man character appears in the film Pixels (2015), with Denis Akiyama playing series creator Toru Iwatani. Iwatani himself makes a cameo at the beginning of the film as an arcade technician.

Pac-man is mentioned in the lyrics of the English indie rock band Kaiser Chief's song 'Oh My God' :

'Knock me down I'll get right back up again, I'll come back stronger than a powered up Pac-Man'

On August 3, 2016, Republican nominee Donald Trump released a video on his Facebook page depicting Democratic nominee Hillary Clinton in the video game with ghosts representing FBI agents, referring to Clinton's email investigation.

On August 21, 2016, in the 2016 Summer Olympics closing ceremony, during a video which showcased Tokyo as the host of the 2020 Summer Olympics, a small segment shows Pac-Man and the ghosts racing against each other eating pac-dots on a running track.

Pac-Man was featured in the Kamen Rider cross-over film, Kamen Rider Heisei Generations: Dr. Pac-Man vs. Ex-Aid & Ghost with Legend Rider, released on December 10, 2016. The film involves Pac-Man being used as a virus which Kamen Rider Ex-Aid, Kamen Rider Ghost, Kamen Rider Drive, Kamen Rider Gaim and Kamen Rider Wizard must fight against. The real identity of Dr. Pac-Man is the main antagonist of the film Michihiko Zaizen, who became a supporting character in the film's sequel webisode series Tricks: Kamen Rider Genm.

References

- Dwyer, James; Dwyer, Brendan (2014). Cult Fiction. Paused Books. p. 14. ISBN 9780992988401.

- Pittman, Jamey (June 16, 2011). "The Pac-Man Dossier". Archived from the original on February 14, 2015. Retrieved November 3, 2015.

- Don Hodges. "Pac-Man's Split-screen level analyzed and fixed". Retrieved April 29, 2008.

- "Pac-Man review at OAFE". Oafe.net. Retrieved November 15, 2012.

- ^ Ramsey, David. "The Perfect Man". Oxford American. Archived from the original on February 29, 2008. Retrieved November 13, 2012.

- "Pac-Man at the Twin Galaxies Official Scoreboard". Twin Galaxies. Archived from the original on July 26, 2008. Retrieved December 28, 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - "Pac-Man [Fastest Completion [Perfect Game]] ARCADE - 03:28:49.00 - David W Race". August 4, 2015. Retrieved January 5, 2016.

- Race, David (May 30, 2013). Perfect Pac-Man: May 22, 2013 - 3hrs 28min 49sec (2 of 2). David Race. Retrieved January 5, 2016 – via YouTube.

- Walton, Mark (January 30, 2017). "Namco founder and "Father of Pac-Man" has died". Ars Technica. Retrieved January 30, 2017.

- Sobel, Jonathan (January 30, 2017). "Masaya Nakamura, Whose Company Created Pac-Man, Dies at 91". New York Times. Retrieved January 30, 2017.

- "Top 25 Smartest Moves in Gaming". Gamespy.com. Archived from the original on February 18, 2009. Retrieved July 26, 2010.

- Kohler, Chris (2005). Power-Up: How Japanese Video Games Gave the World an Extra Life. Brady Games. ISBN 0-7440-0424-1.

- "Daijisen Dictionary entry for ぱくぱく (paku-paku), in Japanese". Retrieved January 27, 2007.

- the JADED the meaning of pakupaku

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

salonwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Lammers, Susan M. (1986). Programmers at Work: Interviews. New York: Microsoft Press. p. 266. ISBN 0-914845-71-3.

- Morris, Chris (March 3, 2011). "Five Things You Never Knew About Pac-Man". Retrieved December 30, 2016.

- "The Collection: Selected Works from Applied Design; Pac-Man". MoMA. Retrieved March 4, 2013.

- ^ Kohler, Chris (May 21, 2010). "Q&A: Pac-Man Creator Reflects on 30 Years of Dot-Eating". Wired. Retrieved July 15, 2010.

- ^ Kent, Steve. Ultimate History of Video Games, p.142. "Before Namco showed Pac-Man to Midway, one change was made to the game. Pac-Man was originally named Puck-Man, a reference to the puck-like shape of the main character. Nakamura worried about American vandals changing the "P" to an "F." To prevent any such occurrence, he changed the name of the game."

- Brian Ashcraft. "This Guy Has a Rare Arcade Cabinet. Is It Real?". Kotaku.

- Cite error: The named reference

classicgamingwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - Bowen, Kevin (2001). "Game of the Week: Defender". ClassicGaming.com. Retrieved August 17, 2006.

- "Pac-Man – The Dot Eaters". The Dot Eaters. Retrieved August 17, 2006.

- Mark J. P. Wolf (2001). The medium of the video game. University of Texas Press. p. 44. ISBN 0-292-79150-X. Retrieved April 9, 2011Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ Mark J. P. Wolf (2008). The video game explosion: a history from PONG to PlayStation and beyond. ABC-CLIO. p. 73. ISBN 0-313-33868-X. Retrieved April 10, 2011.

It would go on to become arguably the most famous video game of all time, with the arcade game alone taking in more than a billion dollars, and one study estimated that it had been played more than 10 billion times during the twentieth century.

- Bill Loguidice; Matt Barton (2009). Vintage games: an insider look at the history of Grand Theft Auto, Super Mario, and the most influential games of all time. Focal Press. p. 181. ISBN 0-240-81146-1. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

The machines were well worth the investment; in total they raked in over a billion dollars worth of quarters in the first year alone.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - Kline, Stephen; Nick Dyer-Witheford; Greig de Peuter (2003). Digital play: the interaction of technology, culture, and marketing (Reprint ed.). Montréal, Quebec: McGill-Queen's University Press. p. 96. ISBN 0-7735-2591-2. Retrieved February 25, 2012.

The game produced one billion dollars in 1980 alone

- "Electronic and Computer Games: The History of an Interactive Medium". Screen. 29 (2): 52–73 . 1988. doi:10.1093/screen/29.2.52. Retrieved January 25, 2012.

Revenue from the game Pac-Man alone was estimated to exceed that from the cinema box-office success Star Wars.

- Cite error: The named reference

nytims nakamurawas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Marlene Targ Brill (2009). America in the 1980s. Twenty-First Century Books. p. 120. ISBN 0-8225-7602-3. Retrieved May 1, 2011Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - Kevin "Fragmaster" Bowen (2001). "Game of the Week: Pac-Man". GameSpy. Retrieved April 9, 2011.

- Infoworld Media Group, Inc (April 12, 1982). "Video arcades rival Broadway theatre and girlie shows in NY". InfoWorld. p. 15. ISSN 0199-6649. Retrieved May 1, 2011Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite web}}:|first1=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ "CPI Inflation Calculator". Bureau of Labor Statistics. Retrieved March 22, 2011.

- ^ Kao, John J. (1989). Entrepreneurship, creativity & organization: text, cases & readings. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. p. 45. ISBN 0-13-283011-6. Retrieved February 12, 2012.

Estimates counted 7 billion coins that by 1982 had been inserted into some 400,000 Pac Man machines worldwide, equal to one game of Pac Man for every person on earth. US domestic revenues from games and licensing of the Pac Man image for T-shirts, pop songs, to wastepaper baskets, etc. exceeded $1 billion.

- "Men's wear, Volume 185". Men's wear. 185. Fairchild Publications. 1982. Retrieved February 28, 2012.

- Cite error: The named reference

CNN-Morriswas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - Cite error: The named reference

Kent-143was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - "Top 10 Highest-Grossing Arcade Games of All Time". USgamer. January 1, 2016. Retrieved January 3, 2016.

- "Electronic Games Magazine". Internet Archive. Retrieved February 1, 2012.

- "Pac Man 'greatest video game'". BBC News. November 13, 2001. Retrieved March 13, 2012.

- McLemore, Greg. "The Top Coin-Operated Videogames of all Times". Killer List of Videogames. Retrieved November 3, 2015.

- Aaron Matteson. "Five Things We Learned From Pac-Man". joystickdivision.com. "This cutscene furthers the plot by depicting a comically large Pac-Man".

- ^ "The Essential 50 Part 10 -- Pac-Man from 1UP.com". 1Up.com. Retrieved November 4, 2015.

- ^ Wilson, Jeffrey L. (June 11, 2010). "The 10 Most Influential Video Games of All Time". PC Magazine. 1. Pac-Man (1980). Retrieved April 19, 2012.

- The ten most influential video games ever, The Times, September 20, 2007

- "Playing With Power: Great Ideas That Have Changed Gaming Forever from 1UP.com". 1Up.com. Retrieved November 4, 2015.

- ^ "Gaming's most important evolutions". GamesRadar+. October 8, 2010. Retrieved November 4, 2015.

- "Space Invaders Deluxe". klov.com. Retrieved March 28, 2011.

- Al-Kaisy, Muhammad (June 10, 2011). "The history and meaning behind the 'Stealth genre'". Gamasutra. Retrieved September 15, 2011.

- David Low (April 2, 2007). "GO3: Kojima Talks Metal Gear History, Future". Gamasutra. Retrieved August 3, 2011.

- Brian Ashcraft (July 16, 2009). "Grand Theft Auto And Pac-Man? "The Same"". Retrieved March 8, 2011.

- "25 years of Pac-Man". MeriStation. July 4, 2005. Retrieved May 6, 2011. (Translation)

- Bailey, Kat (March 9, 2012). "These games inspired Cliff Bleszinski, John Romero, Will Wright, and Sid Meier". Joystiq. Retrieved April 2, 2012.

- Stephan Günzel; Michael Liebe; Dieter Mersch (2008). Sebastian Möring (ed.). Conference Proceedings of The Philosophy of Computer Games 2008. Potsdam University Press. pp. 191–2. ISBN 3-940793-49-3. Retrieved May 6, 2011Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - Book of Games: The Ultimate Reference on PC & Video Games. Book of Games. 2006. p. 24. ISBN 82-997378-0-X. Retrieved May 6, 2011Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - "Game developer". 2 & 5. Miller Freeman. 1995: 62. Retrieved June 6, 2011.

If you made it to the secret Pac-Man level in Castle Wolfenstein, you know what I mean (Pac-Man never would have made it as a three-dimensional game). Though it may be less of a visual feast, two dimensions have a well-established place as an electronic gaming format.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Media, Spin L.L.C. (September 1995). "Children of Doom". Spin. p. 118. ISSN 0886-3032. Retrieved May 6, 2011Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - Gutman, Dan (July 1989). "Nine for '89". Compute!. p. 19. Retrieved November 11, 2013.

- Leonard Herman; Jer Horwitz; Steve Kent; Skyler Miller (2002). "The History of Video Games" (PDF). GameSpot. p. 7. Retrieved March 14, 2012.

- "Creating a World of Clones". Philadelphia Inquirer. October 9, 1983. p. 16.

- Thompson, Adam (Fall 1983). "The King of Video Games is a Woman". Creative Computing Video and Arcade Games. 1 (2): 65.

- Ratcliff, Matthew (August 1988). "Classic Cartridges II". Antic. 7 (4): 24.

- ^ Buchanan, Levi (August 26, 2008). "Top 10 Best-Selling Atari 2600 Games". IGN. Retrieved July 15, 2009.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

timemagwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - "The A-Maze-ing World of Gobble Games". Electronic Games. 1 (3): 62–63 . May 1982. Retrieved February 3, 2012.

- Ellis, David (2004). "The Atari VCS (2000)". Official Price Guide to Classic Video Games. Random House. pp. 98–99. ISBN 0-375-72038-3.

- Buchanan, Levi (November 26, 2008). "Top 10 Videogame Turkeys". IGN. Retrieved July 15, 2009.

- "Mini-Arcades 'Go Gold'". Electronic Games. 1 (9): 13. November 1982. Retrieved February 5, 2012.

- "Coleco Mini-Arcades Go Gold" (PDF). Arcade Express. 1 (1): 4. August 15, 1982. Retrieved February 3, 2012.

- Ciraolo, Michael (October–November 1985). "Top Software / A List of Favorites". II Computing. p. 51. Retrieved January 28, 2015.

- J.F. Archibald, J. Haynes, ed. (1988). "Video Games Are Back". The Bulletin (5609–5616): 134. Retrieved January 29, 2012.

Mindscape, a software company based in Northbrook, sold more than 100,000 copies of Pac Man for the PC last December alone.

- Nguyen, Vincent (May 28, 2008). "First LIVE images and videos of fullscreen Android demos!". Retrieved July 5, 2008.

- "Namco Networks' Pac-Man Franchise Surpasses 30 Million Paid Transactions in the United States on Brew". AllBusiness.com. 2010. Retrieved February 22, 2012.

- "A quick look at some of the new WP7 games from Namco". BestWP7Games. November 9, 2010.

- Cite error: The named reference

1upwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - Worley, Joyce (May 1982). "Women Join the Arcade Revolution". Electronic Games. 1 (3): 30–33 . Retrieved February 3, 2012.

- "Ms. Pac-Man". Killer List of Videogames. Retrieved July 31, 2006.

- Schiesel, Seth (June 6, 2007). "Run, Gobble, Gobble, Run: Vying for Pac-Man Acclaim". The New York Times. Retrieved May 20, 2010.

- "Google gets Pac-Man fever". cnet. May 21, 2010.

- Terdiman, Daniel (May 21, 2010). "Google gets Pac-Man fever". News.cnet.com. Retrieved May 22, 2012.

- "'Insert Coin': Google Doodle Celebrates Pac-Man's 30th Anniversary". ABC. ABC. May 21, 2010. Retrieved May 21, 2010.

- "Pac-Man gobbles up $120M in workplace productivity". .astd.org. May 26, 2010. Archived from the original on February 1, 2014. Retrieved March 9, 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - "CANOE – Technology: Pac-Man gobbles up $120M in workplace productivity". Technology.canoe.ca. Retrieved May 22, 2012.

- "Quit playing Google Pac Man and get back to work, everyone!". Inquisitr.com. May 21, 2010. Retrieved May 22, 2012.

- Terdiman, Daniel (May 21, 2010). "Is playable Pac-Man getting Google's home page banned?". News.cnet.com. Retrieved May 22, 2012.

- "Pac-Man". Google. Retrieved November 3, 2015.

- Michael Calia. "You Can Play Pac-Man on Your City's Streets". Wall Street Journal (blogs). Retrieved March 31, 2015.

- Tom Goldman. "The Escapist : News : Namco Shuts Down Student's Pac-Man Project". Escapistmagazine.com. Retrieved May 22, 2012.

- Ki Mae Huessner. "World's Biggest Pac-Man Is Web Sensation". ABC News Internet Ventures. Retrieved April 13, 2013.

- Coopee, Todd. "Pac-Man Turns 35!". ToyTales.ca.

- "The MB Official Pac-Man Board Game". Retrieved November 4, 2015.

- "The Pac-Star: Pac-Man Rub-Offs Section Index". Retrieved November 4, 2015.

- "The Official Midway's Pac-Man Game Watch Instruction Manual" (PDF) (booklet). Nelsonic Industries. Retrieved November 3, 2015.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "Internet Pinball Machine Database: Bally 'Mr. & Mrs. Pac-Man Pinball'". Retrieved November 4, 2015.

- "Internet Pinball Machine Database: Bally 'Baby Pac-Man'". Retrieved November 4, 2015.

- "The Pac-Page (including database of Pac-Man merchandise and TV show reference)". GameSpy. Archived from the original on April 16, 2009. Retrieved May 7, 2011.

- "Crystal Sky, Namco & Gaga are game again". Crystalsky.com. Retrieved August 11, 2008.

- Jaafar, Ali (May 19, 2008) "Crystal Sky signs $200 million deal". Variety.com. Retrieved September 4, 2008.

- White, Cindy. (June 17, 2010) "E3 2010: Pac-Man Back on TV?". IGN.com. Retrieved July 7, 2010.

- Morris, Chris. (June 17, 2010) "Pac-Man chomps at 3D TV. Variety.com. Retrieved July 7, 2010.

- Ivan-Zadeh, Larushka (August 26, 2010). "Scott Pilgrim Vs The World is almost Spaced in Toronto". Metro. Retrieved March 15, 2012.

- Cite error: The named reference

nlgdwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - "Popular Computing". McGraw-Hill. 1982. Retrieved August 14, 2010.

Pac-Man Fever went gold almost instantly with 1 million records sold.

- Turow, Joseph (2008). Media Today: An Introduction to Mass Communication (3rd ed.). Taylor & Francis. p. 554. ISBN 0-415-96058-4. Retrieved January 29, 2012.

- RIAA Gold & Platinum Searchable Database – Pac-Man Fever. RIAA.com. Retrieved November 1, 2009.

- Dr. Demento's Basement Tapes #4, a Demento Society members-only compilation from 1994, contains the demo. It was never commercially recorded or released.

- "The Vocoder: From Speech-Scrambling To Robot Rock". NPR. May 13, 2010. Retrieved February 4, 2012.

- Carless, Simon (August 29, 2005). "Namco, Sony Music Settle Over Pac-Man Samples". Gamasutra.com. Retrieved September 15, 2012.

- Lai, Marcus (August 29, 2005). "Namco and Sony settle Pac-Man lawsuit". News.punchjump.com. Retrieved September 15, 2012.

- "Learn The Code Book And Beat Video Games". Ludington Daily News. March 1, 1982. p. 25. Retrieved April 30, 2011.

- Uston, Ken (Fall 1983). "Mastering Pac-Man Plus and Super Pac-Man". Creative Computing Video & Arcade Games. 1 (2): 32. Retrieved February 22, 2012.

- "Official site for the stand-up comic, writer, presenter & actor". Marcus Brigstocke. Archived from the original on November 20, 2008. Retrieved March 13, 2009. "If Pacman had affected us as kids we'd be running around in dark rooms, munching pills and listening to repetitive music."

- "About Pac-Manhattan". Pac-Manhattan. 2004. Retrieved July 3, 2009.

- "Roomba Pac-Man Web Site". Retrieved October 10, 2009.

- Lau, Dominic. "Pacman in Vancouver". SFU Computing Science. Archived from the original on May 30, 2009. Retrieved July 3, 2009.

- "Origins of the 'Pac-Man' Defense". The New York Times. January 23, 1988. Retrieved November 20, 2010.

- Brunell, Evan (May 22, 2010). "Popular Video Game Pac-Man Celebrates 30th Anniversary". New England Sports Network. Retrieved April 11, 2012.

- "The Pac-Man Project". UC Berkeley. Archived from the original on July 9, 2013. Retrieved November 3, 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Landry, Lauren (January 11, 2013). "New Year, New Hack: MIT Students Place Pac-Man On Top of the Great Dome". BostInno. Streetwise Media. Retrieved January 11, 2013.

- Dezenski, Lauren (January 11, 2013). "In whimsical retro tribute, Pac-Man appears on MIT's Great Dome". Boston.com. NY Times Co. Retrieved January 11, 2013.

- "Pac-Man".

- "Classic video game characters unite via film 'Pixels'". Philstar. July 23, 2014. Retrieved July 23, 2014.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=requires|archive-url=(help) - Tarek Bazley: Pac-man at 35: the video game that changed the world. Al Jazeera English, 2015-05-25

- "Kaiser Chiefs". Genius. Retrieved November 27, 2016.

- Tani, Maxwell (August 3, 2016). "Donald Trump trolls Hillary Clinton's email scandal with a bizarre "Pac-Mac" parody video". Retrieved August 4, 2016.

- "Mario & Pac-Man Showed Up In The Rio 2016 Olympics Closing Ceremony". August 22, 2016. Retrieved December 30, 2016.

- "Kamen Rider Ex-Aid, Kamen Rider Ghost Crossover Film Opens on December 10". Retrieved December 30, 2016.

Further reading

- Trueman, Doug (November 10, 1999). "The History of Pac-Man". GameSpot. Archived from the original on May 25, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) Comprehensive coverage on the history of the entire series up through 1999. - Müller, Martijn (June 3, 2010). "Tōru Iwatani on how Pac-Man came to be". NG-Gamer.

- Morris, Chris (May 10, 2005). "Pac Man Turns 25". CNN Money.

- Vargas, Jose Antonio (June 22, 2005). "Still Love at First Bite: At 25, Pac-Man Remains a Hot Pursuit". The Washington Post.

- Hirschfeld, Tom. How to Master the Video Games, Bantam Books, 1981. ISBN 0-553-20164-6 Arcade strategy guide to several games including incarnations of Pac-Man. Includes hand drawings of some of the common patterns for use in the arcade Pac-Man. 1982 edition ISBN 0-553-20195-6 covers home versions.

External links

- Pac-Man at the Killer List of Videogames

- Pac-Man at the Arcade History database

- Pac-man 30th Anniversary website

- Twin Galaxies' High-Score Rankings for Pac-Man

| Pac-Man | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Video games | |||||

| Other media | |||||

| Companies | |||||

| Characters | |||||

| Related |

| ||||

- Fictional quartets

- Ghost characters in video games

- Video game characters introduced in 1980

- Villains in animated television series

- Pac-Man characters

- 1980 video games

- Android (operating system) games

- Pac-Man arcade games

- Atari 5200 games

- Atari 8-bit family games

- ColecoVision games

- Commodore 64 games

- Commodore VIC-20 games

- Corporate mascots

- Famicom Disk System games

- FM-7 games

- Game Boy Advance games

- Game Boy games

- Sega Game Gear games

- Ghost video games

- Intellivision games

- IOS games

- IPod games

- Maze games

- Midway video games

- Mobile games

- MSX games

- Namco arcade games

- NEC PC-6001 games

- NEC PC-8001 games

- NEC PC-8801 games

- NEC PC-9801 games

- Neo Geo Pocket Color games

- Nintendo Entertainment System games

- Pac-Man

- SAM Coupé games

- Sharp MZ games

- Sharp X1 games

- Sharp X68000 games

- Tengen (company) games

- Tiger handheld games

- Vertically oriented video games

- Video game franchises

- Virtual Console games

- Windows Phone games

- Xbox 360 Live Arcade games

- ZX Spectrum games

- Z80

- 1980s fads and trends

- Video game franchises introduced in 1980