This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Pjrich (talk | contribs) at 17:07, 9 October 2006 (→Early life: typo). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 17:07, 9 October 2006 by Pjrich (talk | contribs) (→Early life: typo)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)Christopher Columbus (Italian Cristoforo Colombo; Portuguese Cristóvão Colon; Spanish: Cristóbal Colón; Catalan: Cristòfor Colom; c. 1451–May 20, 1506) was a navigator and an admiral for the Crown of Castile whose transatlantic voyages opened the Americas to European exploration and colonization. He is commonly believed to have been from Genoa, although his origins remain disputed.

History places great significance on his original voyage of 1492, although he did not actually reach the mainland until his third voyage in 1498. Likewise, he was not the earliest European explorer to reach the Americas, as there are accounts of European transatlantic contact prior to 1492. However, Columbus' voyage came at a critical time of growing national imperialism and economic competition between developing nation states seeking wealth from the establishment of trade routes and colonies. Therefore, the period before 1492 is known as Pre-Columbian, and the anniversary of this event (Columbus Day) is celebrated throughout the Americas and in Spain and Italy.

Early life

- For controversies about nationality, see National origin

According to the most widely recognized theory, Columbus was born between August and October 1451 in Genoa, one of the most ancient mariner communities of Middle Ages Europe. His father was Domenico Colombo, a middle-class wool weaver working between Genoa and Savona. His mother was Susanna Fontanarossa.. News about Columbus' early years are scarce. He probably received an incomplete education, and spoke Genoese dialect. In one of his writings Columbus claims to have gone to the sea at 10. In the early 1470s, he was at the service of René I of Anjou, in a Genoese ship hired to support his unfortunate attempt to conquer the Kingdom of Naples. Later he allegedly made a trip to Chios, in the Aegean Sea. In May 1476 he took part to an armed convoy set by Genoa to carry a valuable cargo to northern Europe. On August 13, the convoy was intercepted by Portuguese ships near the coast of that country. Columbus was wounded in the battle that ensued, but managed to land at the small town of Ligos. His brother, Bartolomeo lived in Lisbon in that period, working in a cartography workshop.

Background to voyages

Navigational theories

Europe had long enjoyed safe passage to China and India— sources of valued goods such as silk and spices — under the hegemony of the Mongol Empire (the Pax Mongolica, or "Mongol peace"). With the Fall of Constantinople to the Muslims in 1453, the land route to Asia was no longer an easy route. Portuguese sailors took to travelling south around Africa to get to Asia. Columbus had a different idea. By the 1480s, he had developed a plan to travel to the Indies (then construed roughly as all of south and east Asia) by sailing directly west across the "Ocean Sea" (the Atlantic).

It is sometimes claimed that Columbus had difficulty obtaining support for his plan because Europeans believed that the earth was flat. In fact, few people at the time of Columbus´s voyage (and virtually no sailors or navigators) believed this. Most agreed the earth is a sphere. Columbus´s arguments hinged on the circumference of that sphere.

Eratosthenes (276-194 BC) had already, in ancient Alexandrian times, accurately calculated the Earth's circumference, and Aristotle earlier (322 BC) had used observations to deduce that the Earth was not flat. Most scholars accepted Ptolemy's claim that the terrestrial landmass (for Europeans of the time, comprising Eurasia and Africa) occupied 180 degrees of the terrestrial sphere, leaving 180 degrees of water. Indeed, knowledge of the Earth's spherical nature was not limited to scientists. Dante's Divine Comedy is based on a spherical Earth.

Columbus, however, believed the calculations of Marinus of Tyre that the landmass occupied 225 degrees, leaving only 135 degrees of water. Moreover, Columbus believed that 1 degree represented a shorter distance on the earth's surface than was commonly held. Finally, he read maps as if the distances were calculated in Italian miles (1,238 meters). Accepting the length of a degree to be 56⅔ miles, from the writings of Alfraganus, he therefore calculated the circumference of the Earth as 25,255 kilometers at most, and the distance from the Canary Islands to Japan as 3,000 Italian miles (3,700 km). Columbus did not realize that Alfraganus used the much longer Arabic mile of about 1,830 meters. He was not alone in "wishing" the earth was smaller, however. A stunning image of the virtual Earth inside his mind survives in a globe finished in 1492 by Martin Behaim of Nuremberg, Germany, "the Earthapple."

The problem facing Columbus was that experts did not accept his estimate of the distance to the Indies. The true circumference of the Earth is about 40,000 kilometers, and the distance from the Canary Islands to Japan is 19,600 kilometers. No ship in the 15th century could carry enough food to sail from the Canary Islands to Japan. Most European sailors and navigators concluded, correctly, that sailors undertaking a westward voyage from Europe to Asia would die of starvation or thirst long before reaching their destination.

They were right, but Spain, only recently unified through the marriage of Ferdinand and Isabella, was desperate for a competitive edge over other European countries in trade with the East Indies. Columbus promised them that edge.

Columbus' calculations were inaccurate concerning the circumference of the Earth and the distance from the Canary Islands to Japan. But almost all Europeans were mistaken in thinking the aquatic expanse between Europe and Asia was uninterrupted. Although Columbus died believing he had opened up a direct nautical route to Asia, in fact he had established a nautical route between Europe and the Americas. It was this route to the Americas, rather than to Japan, that gave Spain the competitive edge it sought in developing a mercantile empire.

Campaign for funding

Columbus first presented his plan to the court of Portugal in 1485. The king's experts believed that the route would be longer than Columbus thought (the actual distance is even longer than the Portuguese believed), and they denied Columbus' request. He then tried to get backing from the monarchs Ferdinand II of Aragon and Isabella I of Castile, who, by marrying, had united the largest kingdoms of Spain and were ruling them together.

After seven years of lobbying at the Spanish court, where he was kept on a salary to prevent him from taking his ideas elsewhere, he was finally successful in 1492. Ferdinand and Isabella had just conquered Granada, the last Muslim stronghold on the Iberian peninsula, and they received Columbus in Córdoba, in the monarchs' Alcázar or castle. Isabel turned Columbus down on the advice of her confessor, and he was leaving town in despair, when Ferdinand intervened. Isabel then sent a royal guard to fetch him and Ferdinand later rightfully claimed credit for being "the principal cause why those islands were discovered". King Ferdinand is referred to as "losing his patience" in this issue, but this cannot be proven.

About half of the financing was to come from private Italian investors, whom Columbus had already lined up. Financially broke after the Granada campaign, the monarchs left it to the royal treasurer to shift funds among various royal accounts on behalf of the enterprise. Columbus was to be made "Admiral of the Seas" and would receive a portion of all profits. The terms were absurd, but as his own son later wrote, the monarchs did not really expect him to return.

According to the contract that Columbus made with King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella, if Columbus discovered any new islands or mainland, he would:

- be given the rank of Admiral of the Ocean Sea (Atlantic Ocean).

- be appointed Viceroy and Governor of all the new lands.

- have the right to nominate three persons, from whom the sovereigns would choose one, for any office in the new lands.

- be entitled to 10 percent of all the revenues from the new lands in perpetuity; this part was denied to him in the contract, although it was one of his demands.

- have the option of buying one-eighth interest in any commercial venture with the new lands and receive one-eighth of the profits.

However he was arrested in 1500 and removed from these posts, which led to Columbus's son taking legal action to enforce his father's contract. His son was arrested. Many of the smears against Columbus were initated by the Spanish crown during these lengthy court cases (pleitos de Colón).

Voyages

Your Highnesses, as Catholic Christians and Princes who love the holy Christian faith, and the propagation of it, and who are enemies of the sect of Mahoma and to all idolatries and heresies, resolved to send me, Cristobal Colon, to the said parts of India to see the said princes, and the cities and lands, and their disposition, with a view that they might be converted to our holy faith; and ordered that I should not go by land to the eastward, as had been customary, but that I should go by way of the west, wither up to this day, we do not know for certain that any one has gone.

— Christopher Columbus, Journal of His First Voyage, Markham, p.16

First voyage

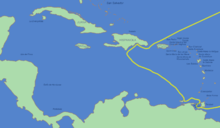

On the evening of August 3, 1492, Columbus departed from Palos with three ships; one larger "Nao", the Santa Maria (first mate-Joseph Vincent) and two smaller "caravels", the Niña (first mate-Anthony Petane) and the Pinta. The ships were property of Juan de la Cosa and the Pinzón brothers (Martin and Vicente Yáñez), but the monarchs forced the Palos inhabitants to contribute to the expedition. Columbus first sailed to the Canary Islands, which was owned by Castile, where he restocked the provisions and made repairs, and on September 6, he started what turned out to be a five-week voyage across the ocean.

A legend is that the crew grew so homesick and fearful that they threatened to sail back to Spain. Although the actual situation is unclear, most likely the sailors' resentments merely amounted to complaints or suggestions.

After 29 days out of sight of land, on October 7, 1492, as recorded in the ship's log the crew spotted shore birds flying west, and they changed direction to make their landfall. A later comparison of dates and migratory patterns leads to the conclusion that the birds were Eskimo curlews and American golden plovers.

Land was sighted at 2 a.m. on October 12, by a sailor named Rodrigo de Triana (also known as Juan Rodriguez Bermejo) aboard Pinta. Columbus called the island (in what is now The Bahamas) San Salvador, although the natives called it Guanahani. Exactly which island in the Bahamas this corresponds to is an unresolved topic; prime candidates are Samana Cay, Plana Cays, or San Salvador Island (named San Salvador in 1925 in the belief that it was Columbus' San Salvador). The indigenous people he encountered, the Lucayan, Taíno or Arawak, were peaceful and friendly. Columbus proceeded to observe the natives and how they went about. He wrote of the Indians:

…we might form great friendship, for I knew that they were a people who could be more easily freed and converted to our holy faith by love than by force, gave to some of them red caps, and glass beads to put round their necks, and many other things of little value, which gave them great pleasure, and made them so much our friends that it was a marvel to see. They afterwards came to the ship’s boats where we were, swimming and bringing us parrots, cotton threads in skeins, darts, and many other things; and we exchanged them for other things that we gave them, such as glass beads and small bells. In fine, they took all, and gave what they had with good will. It appeared to me to be a race of people very poor in everything.…They are very well made, with very handsome bodies, and very good countenances . They neither carry nor know anything of arms, for I showed them swords and they took them by the blade and cut themselves through ignorance. They have no iron…I saw some with marks of wounds on their bodies, and I made signs to ask what it was, and they gave me to understand that people from other adjacent islands came with the intention of seizing them, and that they defended themselves. I believe, and still believe, that they come here from the mainland to take them prisoners. They should be good servants and intelligent, for I observe that they quickly took in what was said to them, and I believe that they would easily become Christians, as it appeared to me that they had no religion.''

— Christopher Columbus, Journal of His First Voyage, Markham, pp. 37-38

Columbus also explored the northeast coast of Cuba (landed on October 28) and the northern coast of Hispaniola, by December 5. Here, the Santa Maria ran aground on Christmas morning 1492 and had to be abandoned. He was received by the native cacique Guacanagari, who gave him permission to leave some of his men behind. Columbus founded the settlement La Navidad and left 39 men.

On January 15, 1493, he set sail for home by way of the Azores.

"He wrestled his ship against the wind and ran into a fierce storm." Actually, crossing the Atlantic in winter, the winds north of Florida and the Bahamas would mostly be favorable, somewhere west of north or south. By the time he arrived off Portugal, though, the west wind would make the whole Iberian Peninsula a dangerous lee shore in bad weather.

Leaving the island of Santa Maria in the Azores, Columbus headed for Spain, but another storm forced him into Lisbon. He anchored next to the King's harbour patrol ship on March 4, 1493, where he was told a fleet of 100 caravels had been lost in the storm. Astoundingly, both the Niña and the Pinta were spared. Not finding the King John in Lisbon, Columbus wrote a letter to him and waited for the king's reply. The king requested that Columbus go to Vale do Paraíso to meet with him. Some have speculated that his landing in Portugal was intentional.

Relations between Portugal and Castile were poor at the time. Columbus went to meet with the king at Vale do Paraíso (north of Lisbon). After spending more than one week in Portugal, he set sail for Spain. Word of his finding new lands rapidly spread throughout Europe. He reached Spain on March 15.

He was received as a hero in Spain. He displayed several kidnapped natives and what gold he had found to the court, as well as the previously unknown tobacco plant, the pineapple fruit, the turkey and the sailor's first love, the hammock. He did not bring any of the coveted East Indies spices, such as the exceedingly expensive black pepper, ginger or cloves. In his log, he wrote "there is also plenty of ají, which is their pepper, which is more valuable than black pepper, and all the people eat nothing else, it being very wholesome" (Turner, 2004, P11). The word ají is still used in South American Spanish for chili peppers.

In his first journey, Columbus visited San Salvador in the Bahamas (which he was convinced was Japan), Cuba (which he thought was China) and Haiti (where he found gold).

Second voyage

Admiral Columbus left from Cádiz, Spain, to find new territories on September 24, 1493, with 17 ships carrying supplies, and about 1,200 men to peacefully colonize the region. It goes without saying that this was in direct competition with Portugal. On October 13, the ships left the Canary Islands as they had before, following a more southerly course.

On November 3 1493, Columbus sighted a rugged island that he named Dominica. On the same day, he landed at Marie-Galante, which he named Santa Maria la Galante. After sailing past Les Saintes (Todos los Santos), he arrived at Guadaloupe (Santa Maria de Guadalupe), which he explored between November 4 and November 10, 1493. The exact course of his voyage through the Lesser Antilles is debated, but it seems likely that he turned north, sighting and naming several islands including Montserrat (Santa Maria de Monstserrate), Antigua (Santa Maria la Antigua), Redondo (Santa Maria la Redonda), Nevis (Santa María de las Nieves), Saint Kitts (San Jorge), Sint Eustatius (Santa Anastasia), Saba (San Cristobal), Saint Martin (San Martin), and Saint Croix (Santa Cruz). He also sighted the island chain of the Virgin Islands, which he named Santa Ursula y las Once Mil Virgines, and named the islands of Virgin Gorda, Tortola, and Peter Island (San Pedro).

He continued to the Greater Antilles, and landed at Puerto Rico (San Juan Bautista) on November 19, 1493. The first skirmish between Americans and Europeans since the Vikings took place when his men rescued two boys who had just been castrated by their captors.

On November 22, he returned to Hispaniola, where he found his colonists had fallen into dispute with natives in the interior and had been killed, but he did not accuse Chief Guacanagari, his ally, of any wrongdoing. Another Chief, named Caonabo, was charged and became the earliest known American native resistence fighter. Columbus established a new settlement at Isabella, on the north coast of Hispaniola, where gold had first been found, but it was a poor location and the settlement was short-lived. He spent some time exploring the interior of the island for gold. Finding some, he established a small fort in the interior. He left Hispaniola on April 24, 1494, and arrived at Cuba (which he named Juana) on April 30 and Jamaica on May 5. He explored the south coast of Cuba, which he believed to be a peninsula rather than an island, and several nearby islands including the Isle of Youth (La Evangelista), before returning to Hispaniola on August 20.

Before he left Spain on his second voyage, Columbus had been directed by Ferdinand and Isabella to maintain friendly, even loving, relations with the natives. He nevertheless sent a letter to the monarchs proposing to enslave some of the native peoples, specifically the Caribs, on the grounds of their aggressiveness and their status as enemies of the Taino. Although his petition was refused by the Crown, in February 1495 Columbus took 1,600 Arawak (a different tribe, who were also hunted by the Carib) as slaves. There was no room for about 400 of them and they were released.

The many voyages of discovery did not pay for themselves; there was no funding for pure science in the Renaissance. Columbus had planned with Isabella to set up trading posts with the cities of the Far East made famous by Marco Polo, but which had been blockaded as described above. Of course, Columbus would never find Cathay (China) or Zipangu (Japan), and there was no longer any Great Kahn. Slavery was practiced widely at that time, amongst many peoples of the world, including some Indians. For the Portuguese — from whom Columbus received most of his maritime training — slavery had resulted in the first financial return on a 75-year investment in Africa.

Five hundred sixty slaves were shipped to Spain; 200 died en route and half the remainder were ill when they arrived. After legal proceedings, some survivors were released and ordered to be shipped home, others sent by Isabella to be galley slaves. Columbus, desperate to repay his investors, failed to realize that Isabella and Ferdinand did not plan to follow Portuguese policy in this respect. Rounding up the slaves led to the first major battle between the Spanish and the natives in the New World.

Columbus also imposed a tribute system similar to that of the Aztec on the mainland. The natives in Cicao on Haiti all those above 14 years of age were required to find a certain quota of gold, to be signified by a token placed around their necks. Those who failed to reach their quota would have their hands chopped off. Despite such extreme measures, Columbus did not manage to obtain much and many "settlers" were unhappy with the climate and disillusioned about their chances of getting rich quick. A classic gold rush had been set off that would have tragic consequences for the Caribbean, though anthropologists have shown there was more intermarriage and assimilation than previously believed (see the Black Legend). Columbus allowed settlers to return home with any Indian women with whom they had started families or, to Isabella's fury, owned as slaves.

From Haiti he finally returned to Spain.

Third voyage and arrest

On May 30, 1498, Columbus left with six ships from Sanlúcar, Spain, for his third trip to the New World. He was accompanied by the young Bartolomé de Las Casas, who would later provide partial transcripts of Columbus' logs.

Columbus led the fleet to the Portuguese island of Porto Santo, his wife's native land. He then sailed to Madeira and spent some time there with the Portuguese captain João Gonçalves da Camara before sailing to the Canary Islands and Cape Verde. Columbus landed on the south coast of the island of Trinidad on July 31. From August 4 through August 12, he explored the Gulf of Paria which separates Trinidad from Venezuela. He explored the mainland of South America, including the Orinoco River. He also sailed to the islands of Chacachacare and Margarita Island and sighted and named Tobago (Bella Forma) and Grenada (Concepcion). He described the new lands as belonging to a previously unknown new continent, but he pictured it hanging from China, bulging out to make the earth pear-shaped.

Columbus returned to Hispaniola on August 19 to find that many of the Spanish settlers of the new colony were discontent, having been misled by Columbus about the supposedly bountiful riches of the new world. Columbus repeatedly had to deal with rebellious settlers and natives. He had some of his crew hanged for disobeying him. A number of returned settlers and friars lobbied against Columbus at the Spanish court, accusing him of mismanagement. The king and queen sent the royal administrator Francisco de Bobadilla in 1500, who upon arrival (August 23) detained Columbus and his brothers and had them shipped home. In 2005, a long lost state report was rediscovered depicting Columbus as a particularly cruel ruler; see the section "Governorship" below for more information. The report may explain part of the reasons for the Spanish Crown's decision to remove Columbus from his position as first governor of the Indies. Columbus refused to have his shackles removed on the trip to Spain, during which he wrote a long and pleading letter to the Spanish monarchs. They accepted his letter and let Columbus and his brothers go free.

Although he regained his freedom, he did not regain his prestige and lost all his titles including the governorship. As an added insult, the Portuguese had won the race to the Indies: Vasco da Gama returned in September 1499 from a trip to India, having sailed east around Africa.

Fourth voyage

Nevertheless, Columbus made a fourth voyage, nominally in search of the Strait of Malacca to the Indian Ocean.

Accompanied by his brother Bartolomeo and his 13-year-old son Fernando, he left Cádiz, Spain on May 11, 1502, with the ships Capitana, Gallega, Vizcaína and Santiago de Palos. He sailed to Arzila on the Moroccan coast to rescue the Portuguese soldiers who he heard were under siege by the Moors. On June 15, they landed at Carbet on the island of Martinique (Martinica). A hurricane was brewing, so he continued on, hoping to find shelter on Hispaniola. He arrived at Santo Domingo on June 29, but was denied port, and the new governor refused to listen to his storm prediction. Instead, while Columbus's ships sheltered at the mouth of the Jaina River, the first Spanish treasure fleet sailed into the hurricane. The only ship to reach Spain had Columbus's money and belongings on it, and all of his former enemies (and a few friends) had drowned.

After a brief stop at Jamaica, he sailed to Central America, arriving at Guanaja (Isla de Pinos) in the Bay Islands off the coast of Honduras on July 30. Here Bartolomeo found native merchants and a large canoe, which was described as "long as a galley" and was filled with cargo. On August 14, he landed on the American mainland at Puerto Castilla, near Trujillo, Honduras. He spent two months exploring the coasts of Honduras, Nicaragua, and Costa Rica, before arriving in Almirante Bay, Panama on October 16.

In Panama, he learned from the natives of gold and a strait to another ocean. After much exploration, he established a garrison at the mouth of Rio Belen in January 1503. On April 6, one of the ships became stranded in the river. At the same time, the garrison was attacked, and the other ships were damaged. He left for Hispaniola on April 16, but sustained more damage in a storm off the coast of Cuba. Unable to travel any farther, the ships were beached in St. Ann's Bay, Jamaica, on June 25, 1503.

Columbus and his men were stranded on Jamaica for a year. Two Spaniards, with native paddlers, were sent by canoe to get help from Hispaniola. In the meantime, in a desperate effort to induce the natives to continue provisioning him and his hungry men, he successfully intimidated the natives by correctly predicting a lunar eclipse, using astronomic tables made by Rabbi Abraham Zacuto who was working for the king of Portugal. Help finally arrived on June 29, 1504, and Columbus and his men arrived in [[Sanl&

- Encyclopaedia Britannica, 1993 ed., Vol. 16, pp. 605ff. And Morison, Christopher Columbus, 1955 ed., pp. 14ff

- Sources indicate that the ships were never officially named

- Clements R. Markham, ed., The Journal of Christopher Columbus (during His First Voyage, 1492-93), London: The Hakluyt Society, 1893, p. 35.

- Philips and Philips, The Worlds of Christopher Columbus