This is an old revision of this page, as edited by 185.159.216.196 (talk) at 08:41, 9 October 2017 (Made it better). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 08:41, 9 October 2017 by 185.159.216.196 (talk) (Made it better)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) "Trumpeter" redirects here. For other uses, see Trumpeter (disambiguation) and Trumpet (disambiguation). B♭ trumpet B♭ trumpet | |

| Brass instrument | |

|---|---|

| Classification |

Brass |

| Hornbostel–Sachs classification | 423.233 (Valved aerophone sounded by lip movement) |

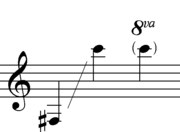

| Playing range | |

Written range: | |

| Related instruments | |

| Flugelhorn, cornet, cornett, bugle, natural trumpet, bass trumpet, post horn, Roman tuba, buccina, cornu, lituus, shofar, dord, dung chen, sringa, shankha, lur, didgeridoo, Alphorn, Russian horns, serpent, ophicleide, piccolo trumpet, horn, alto horn, baritone horn, pocket trumpet | |

| Part of a series on |

| Musical instruments |

|---|

| Woodwinds |

| Brass instruments |

|

String instrumentsBowed

Plucked |

| Percussion |

| Keyboards |

| Others |

A trumpet is a blown musical instrument commonly used in classical and jazz ensembles. The trumpet group contains the instruments with the highest register in the brass family. Trumpet-like instruments have historically been used as signaling devices in battle or hunting, with examples dating back to at least 1500 BC; they began to be used as musical instruments only in the late 14th or early 15th century. Trumpets, which are blow horns are used in art music styles, for instance in orchestras, concert bands, and jazz ensembles, as well as in popular music. They are played by blowing air through nearly-closed lips (called the player's embouchure), producing a "buzzing" sound that starts a standing wave vibration in the air column inside the instrument. Since the late 15th century they have primarily been constructed of brass tubing, usually bent twice into a rounded rectangular shape.

There are many distinct types of trumpet, with the most common being pitched in B♭ (a transposing instrument), having a tubing length of about 1.48 m (4 ft 10 in). Early trumpets did not provide means to change the length of tubing, whereas modern instruments generally have three (or sometimes four) valves in order to change their pitch. Most trumpets have valves of the piston type, while some have the rotary type. The use of rotary-valved trumpets is more common in orchestral settings, although this practice varies by country. Each valve, when engaged, increases the length of tubing, lowering the pitch of the instrument. A musician who plays the trumpet is called a trumpet player or trumpeter.

Etymology

The English word "trumpet" was first used in the late 14th century. The word came from Old French "trompette", which is a "diminutive of trompe". The word "trump", meaning "trumpet," was first used in English in 1300. The word comes "from Old French trompe "long, tube-like musical wind instrument" (12c.), cognate with Provençal tromba, Italian tromba, all probably from a Germanic source (compare Old High German trumpa, Old Norse trumba "trumpet"), of imitative origin."

History

The earliest trumpets date back to 1500 BC and earlier. The bronze and silver trumpets from Tutankhamun's grave in Egypt, bronze lurs from Scandinavia, and metal trumpets from China date back to this period. Trumpets from the Oxus civilization (3rd millennium BC) of Central Asia have decorated swellings in the middle, yet are made out of one sheet of metal, which is considered a technical wonder.

The Shofar, made from a ram horn and the Hatzotzeroth, made of metal, are both mentioned in the Bible. They were played in Solomon's Temple around 3000 years ago. They were said to be used to blow down the walls of Jericho. They are still used on certain religious days. The Salpinx was a straight trumpet 62 inches (1,600 mm) long, made of bone or bronze. Salpinx contests were a part of the original Olympic Games.

The Moche people of ancient Peru depicted trumpets in their art going back to AD 300. The earliest trumpets were signaling instruments used for military or religious purposes, rather than music in the modern sense; and the modern bugle continues this signaling tradition.

Improvements to instrument design and metal making in the late Middle Ages and Renaissance led to an increased usefulness of the trumpet as a musical instrument. The natural trumpets of this era consisted of a single coiled tube without valves and therefore could only produce the notes of a single overtone series. Changing keys required the player to change crooks of the instrument. The development of the upper, "clarino" register by specialist trumpeters—notably Cesare Bendinelli—would lend itself well to the Baroque era, also known as the "Golden Age of the natural trumpet." During this period, a vast body of music was written for virtuoso trumpeters. The art was revived in the mid-20th century and natural trumpet playing is again a thriving art around the world. Many modern players in Germany and the UK who perform Baroque music use a version of the natural trumpet fitted with three or four vent holes to aid in correcting out-of-tune notes in the harmonic series.

The melody-dominated homophony of the classical and romantic periods relegated the trumpet to a secondary role by most major composers owing to the limitations of the natural trumpet. Berlioz wrote in 1844:

Notwithstanding the real loftiness and distinguished nature of its quality of tone, there are few instruments that have been more degraded (than the trumpet). Down to Beethoven and Weber, every composer – not excepting Mozart – persisted in confining it to the unworthy function of filling up, or in causing it to sound two or three commonplace rhythmical formulae.

The attempt to give the trumpet more chromatic freedom in its range saw the development of the keyed trumpet, but this was a largely unsuccessful venture due to the poor quality of its sound.

Although the impetus for a tubular valve began as early as 1793, it was not until 1818 that Friedrich Bluhmel and Heinrich Stölzel made a joint patent application for the box valve as manufactured by W. Schuster. The symphonies of Mozart, Beethoven, and as late as Brahms, were still played on natural trumpets. Crooks and shanks (removable tubing of various lengths) as opposed to keys or valves were standard, notably in France, into the first part of the 20th century. As a consequence of this late development of the instrument's chromatic ability, the repertoire for the instrument is relatively small compared to other instruments. The 20th century saw an explosion in the amount and variety of music written for the trumpet.

Construction

The trumpet is constructed of brass tubing bent twice into a rounded oblong shape. As with all brass instruments, sound is produced by blowing air through closed lips, producing a "buzzing" sound into the mouthpiece and starting a standing wave vibration in the air column inside the trumpet. The player can select the pitch from a range of overtones or harmonics by changing the lip aperture and tension (known as the embouchure).

The mouthpiece has a circular rim, which provides a comfortable environment for the lips' vibration. Directly behind the rim is the cup, which channels the air into a much smaller opening (the back bore or shank) that tapers out slightly to match the diameter of the trumpet's lead pipe. The dimensions of these parts of the mouthpiece affect the timbre or quality of sound, the ease of playability, and player comfort. Generally, the wider and deeper the cup, the darker the sound and timbre.

Modern trumpets have three (or infrequently four) piston valves, each of which increases the length of tubing when engaged, thereby lowering the pitch. The first valve lowers the instrument's pitch by a whole step (2 semitones), the second valve by a half step (1 semitone), and the third valve by one-and-a-half steps (3 semitones). When a fourth valve is present, as with some piccolo trumpets, it usually lowers the pitch a perfect fourth (5 semitones). Used singly and in combination these valves make the instrument fully chromatic, i.e., able to play all twelve pitches of classical music. For more information about the different types of valves, see Brass instrument valves.

The pitch of the trumpet can be raised or lowered by the use of the tuning slide. Pulling the slide out lowers the pitch; pushing the slide in raises it. To overcome the problems of intonation and reduce the use of the slide, Renold Schilke designed the tuning-bell trumpet. Removing the usual brace between the bell and a valve body allows the use of a sliding bell; the player may then tune the horn with the bell while leaving the slide pushed in, or nearly so, thereby improving intonation and overall response.

A trumpet becomes a closed tube when the player presses it to the lips; therefore, the instrument only naturally produces every other overtone of the harmonic series. The shape of the bell makes the missing overtones audible. Most notes in the series are slightly out of tune and modern trumpets have slide mechanisms for the first and third valves with which the player can compensate by throwing (extending) or retracting one or both slides, using the left thumb and ring finger for the first and third valve slides respectively.

Types

The most common type is the B♭ trumpet, but A, C, D, E♭, E, low F, and G trumpets are also available. The C trumpet is most common in American orchestral playing, where it is used alongside the B♭ trumpet. Its slightly smaller size gives it a brighter sound, clearer projection, and crisper articulation. Orchestral trumpet players are adept at transposing music at sight, frequently playing music written for the A, B♭, D, E♭, E, or F trumpet on the C trumpet or B♭ trumpet.

The smallest trumpets are referred to as piccolo trumpets. The most common of these are built to play in both B♭ and A, with separate leadpipes for each key. The tubing in the B♭ piccolo trumpet is one-half the length of that in a standard B♭ trumpet. Piccolo trumpets in G, F and C are also manufactured, but are less common. Many players use a smaller mouthpiece on the piccolo trumpet, which requires a different sound production technique from the B♭ trumpet and can limit endurance. Almost all piccolo trumpets have four valves instead of the usual three — the fourth valve lowers the pitch, usually by a fourth, to assist in the playing of lower notes and to create alternate fingerings that facilitate certain trills. Maurice André, Håkan Hardenberger, David Mason, and Wynton Marsalis are some well-known trumpet players known for their additional virtuosity on the piccolo trumpet.

Trumpets pitched in the key of low G are also called sopranos, or soprano bugles, after their adaptation from military bugles. Traditionally used in drum and bugle corps, sopranos have featured both rotary valves and piston valves.

The bass trumpet is usually played by a trombone player, being at the same pitch. Bass trumpet is played with a shallower trombone mouthpiece, and music for it is written in treble clef. The most common keys for bass trumpets are C and B♭. Both C and B♭ bass trumpets are transposing instruments sounding an octave (C) or a major ninth (B♭) lower than written.

The modern slide trumpet is a B♭ trumpet that has a slide instead of valves. It is similar to a soprano trombone. The first slide trumpets emerged during the Renaissance, predating the modern trombone, and are the first attempts to increase chromaticism on the instrument. Slide trumpets were the first trumpets allowed in the Christian church.

The historical slide trumpet was probably first developed in the late 14th century for use in alta capella wind bands. Deriving from early straight trumpets, the Renaissance slide trumpet was essentially a natural trumpet with a sliding leadpipe. This single slide was rather awkward, as the entire corpus of the instrument moved, and the range of the slide was probably no more than a major third. Originals were probably pitched in D, to fit with shawms in D and G, probably at a typical pitch standard near A=466 Hz. As no known instruments from this period survive, the details—and even the existence—of a Renaissance slide trumpet is a matter of conjecture and debate among scholars.

Some slide trumpet designs saw use in England in the 18th century.

-

"History of the Trumpet (According to the New Harvard Dictionary of Music)". petrouska.com. Archived from the original on 2008-06-08. Retrieved 2014-12-17.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Clint McLaughlin, The No Nonsense Trumpet From A-Z (1995), 7-10.

- "Trumpet". www.etymonline.com. Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 20 May 2017.

- "Trumpet". www.etymonline.com. Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 20 May 2017.

- "Trump". www.etymonline.com. Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 20 May 2017.

- Edward Tarr, The Trumpet (Portland, Oregon: Amadeus Press, 1988), 20-30.

- "Trumpet with a swelling decorated with a human head," Musée du Louvre

- "History of the trumpet".

- "History of the trumpet".

- Berrin, Katherine & Larco Museum. The Spirit of Ancient Peru:Treasures from the Museo Arqueológico Rafael Larco Herrera. New York: Thames and Hudson, 1997.

- "Chicago Symphony Orchestra – Glossary – Brass instruments". cso.org. Retrieved 2008-05-03.

- "History of the trumpet".

- John Wallace and Alexander McGrattan, The Trumpet, Yale Musical Instrument Series (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2011): 239. ISBN 978-0-300-11230-6.

- Berlioz, Hector (1844). Treatise on modern Instrumentation and Orchestration. Edwin F. Kalmus, NY, 1948.

- "Trumpet, Brass Instrument". dsokids.com. Retrieved 2008-05-03.

- Bloch, Dr. Colin (August 1978). "The Bell-Tuned Trumpet". Retrieved 25 February 2010.

- D. J. Blaikley, "How a Trumpet Is Made. I. The Natural Trumpet and Horn", The Musical Times, January 1, 1910, p. 15.

- Tarr

- "IngentaConnect More about Renaissance slide trumpets: fact or fiction?". ingentaconnect.com. Retrieved 2008-05-03.

-

"JSTOR: Notes, Second Series". 54. 1997: 484–485. JSTOR 899543.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)