This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Burkem (talk | contribs) at 20:46, 31 October 2006. The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 20:46, 31 October 2006 by Burkem (talk | contribs)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)

Charlemagne (742 or 747 – 28 January 814) (also Charles the Great; from Latin, Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)) was the King of the Franks (768–814) who conquered Italy and took the Iron Crown of Lombardy in 774 and, on a visit to Rome in 800, was crowned Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)]] ("Emperor of the Romans") by Pope Leo III on Christmas Day, presaging the revival of the Roman imperial tradition in the West in the form of the Holy Roman Empire. By his foreign conquests and internal reforms, Charlemagne helped define Western Europe and the Middle Ages. His rule is also associated with the Carolingian Renaissance, a revival of the arts and education in the West.

The son of King Pippin the Short and Bertrada of Laon, he succeeded his father and co-ruled with his brother Carloman until the latter's death in 771. Charlemagne continued the policy of his father towards the papacy and became its protector, removing the Lombards from power in Italy, and waging war on the Saracens who menaced his realm from Spain. It was during one of these campaigns that he experienced the worst defeat of his life at Roncesvalles (778). He also campaigned against the peoples to his east, especially the Saxons, and after a protracted war subjected them to his rule. By converting them to Christianity, he integrated them into his realm and thus paved the way for the later Ottonian Dynasty.

Today regarded as the founding father of both France and Germany and sometimes as the Father of Europe, as he was the first ruler of a united Western Europe since the fall of the Roman Empire.

Background

| Carolingian dynasty |

|---|

|

Pippinids

|

Arnulfings

|

Carolingians

|

After the Treaty of Verdun (843)

|

The Franks, originally a pagan, barbarian, Germanic people who migrated over the River Rhine in the late fifth century into a crumbling Roman Empire, were, by the early eighth century, the rulers of Gaul and a good portion of central Europe east of the Rhine and followers of the Catholic faith. However, their ancient dynasty of kings, the Merovingians, had gradually declined into a state of powerlessness, for which they have been dubbed Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), do-nothing kings. Practically all government powers of any consequence were exercised by their chief officer, the mayor of the palace or major domus.

In 687 Pippin of Heristal, mayor of the palace of Austrasia, ended the strife between various kings and their mayors with his victory at Tertry and practically became the sole governor of the entire Frankish kingdom. Pippin himself was the grandson of two most important figures of the Austrasian Kingdom, Saint Arnulf of Metz and Pippin of Landen. Pippin the Middle was eventually succeeded by his illegitimate son Charles, later also called Martel (the Hammer). After 737, Charles governed the Franks without a king on the throne but desisted from calling himself King. Charles was succeeded by his sons Carloman and Pippin, the father of Charlemagne. To curb separatism in the periphery of the realm, the brothers placed Childeric III on the throne, who was to be the last Merovingian king.

After Carloman resigned his office, Pippin had Childeric III deposed with the Pope's approval. In 751, Pippin was elected and anointed King of the Franks and in 754, Pope Stephen II again anointed him and his young sons. Thus was the Merovingian dynasty replaced by the Carolingian dynasty, named after Pippin's father Charles Martel and its most famous member, Charlemagne.

Pippin's sons, Charlemagne and Carloman, immediately became joint heirs to the great realm which already covered most of western and central Europe. Under the new dynasty, the Frankish kingdom spread to encompass an area including most of Western Europe. The division of that kingdom formed France and Germany; and the religious, political, and artistic evolutions originating from a centrally-positioned Francia made a defining imprint on the whole of Western Europe. The foundations of Europe—as more than a geographic entity—were laid in the Dark Ages, largely out of the Frankish Empire.

Date and place of birth

Charlemagne's birthday was believed to be April 2, 742; however several factors led to reconsideration of this traditional date. First, the year 742 was calculated from his age given at death, rather than attestation within primary sources. Another date is given in the Annales Petarienses, April 1, 747. In that year, April 1 is Easter. The birth of an Emperor on Easter is a coincidence likely to provoke comment, but there is no such comment documented in 747, leading some to suspect that the Easter birthday was a pious fiction concocted as a way of honoring the Emperor. Other commentators weighing the primary records have suggested that the birth was one year later, 748. At present, it is impossible to be certain of the date of the birth of Charlemagne. The best guesses include April 1, 747, after April 15, 747, or April 1, 748, in Herstal (where his father was born), a city close to Liège, in Belgium, the region from which both the Meroving and Caroling families originate. He went to live in his father's villa in Jupille when he was around 7, which caused Jupille to be listed as possible place of birth in almost every history book. Other cities have been suggested, including, Prüm, Düren, or Aachen.

Personal appearance

Charlemagne's personal appearance is not known from any contemporary portrait, but it is known rather famously from a good description by Einhard, author of the biographical Vita Caroli Magni. He is well known to have been tall, stately, and fair-haired, with a disproportionately thick neck. His skeleton was measured during the 18th century and his height was determined to be 193 cm (6 ft 4 in ), and as Einhard tells it in his twenty-second chapter:

- Charles was large and strong, and of lofty stature, though not disproportionately tall (his height is well known to have been seven times the length of his foot); the upper part of his head was round, his eyes very large and animated, nose a little long, hair fair, and face laughing and merry. Thus his appearance was always stately and dignified, whether he was standing or sitting; although his neck was thick and somewhat short, and his belly rather prominent; but the symmetry of the rest of his body concealed these defects. His gait was firm, his whole carriage manly, and his voice clear, but not so strong as his size led one to expect.

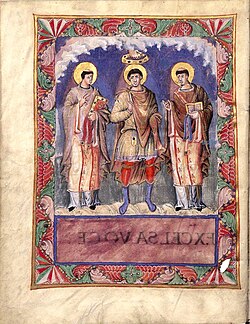

The Roman tradition of realistic personal portraiture was in complete eclipse at this time, where individual traits were submerged in iconic typecastings. Charlemagne, as an ideal ruler, ought to be portrayed in the corresponding fashion, any contemporary would have assumed. The images of enthroned Charlemagne, God's representative on Earth, bear more connections to the icons of Christ in majesty than to modern (or antique) conceptions of portraiture. Charlemagne in later imagery (as in the Dürer portrait) is often portrayed with flowing blond hair, due to a misunderstanding of Einhard, who describes Charlemagne as having canitie pulchra, or "beautiful white hair", which has been rendered as blonde or fair in many translations. The Latin word for blond is flavus, and rutilo, meaning auburn, is the word Tacitus uses for the hair of Germanic peoples.

Dress

Charlemagne wore the traditional, inconspicuous, and distinctly non-aristocratic costume of the Frankish people, described by Einhard thus:

- He used to wear the national, that is to say, the Frank dress: next to his skin a linen shirt and linen breeches, and above these a tunic fringed with silk; while hose fastened by bands covered his lower limbs, and shoes his feet, and he protected his shoulders and chest in winter by a close-fitting coat of otter or marten skins.

He accessorised too, wearing a blue cloak and always carrying a sword with him. The typical sword was of a golden or silver hilt. However, he wore fancy jewelled swords to banquets or ambassadorial receptions. Nevertheless:

- He despised foreign costumes, however handsome, and never allowed himself to be robed in them, except twice in Rome, when he donned the Roman tunic, chlamys, and shoes; the first time at the request of Pope Hadrian, the second to gratify Leo, Hadrian's successor.

He could rise to the occasion when necessary. On great feast days, he wore embroidery and jewels on his clothing and shoes. He had a golden buckle for his cloak on such occasions and would appear with his great diadem, but he despised such apparel, according to Einhard, and usually dressed as the common people.

Language

Charlemagne's native tongue is a matter of controversy. He spoke the Germanic language of the Franks of his day, which should be called Old Frankish, but linguists differ on the identity and periodisation of the language, some going so far as to say that he did not speak Old Frankish, as Charlemagne was born in 742 or 747 and Frankish became extinct during the early 7th century, so that it is reconstructed from loanwords in its descendant, Old Low Franconian, also called Old Dutch, and Old French. Linguists know very little about Old Frankish, as it attested mainly as phrases and words in the law codes of the main Frankish tribes (especially those of the Salian and Ripuarian Franks), which are written in Latin interspersed with barbarisms.

The area of Charlemagne's birth does not make determination of his native language easier. Most historians agree he was born around Liège, like his father, but some say he was born in or around Aachen, some fifty kilometres away. At that time, this was an area of great linguistic diversity. If we take Liège (around 750) as the centre, we find Low Franconian in the north and northwest, Gallo-Romance (the ancestor of Old French) in the south and southwest and various Old High German dialects in the east. If Gallo-Romance is excluded, that means he either spoke Old Low Franconian or an Old High German dialect, probably with a strong Frankish influence.

Apart from his native language he also spoke some Latin and understood a bit of Greek.

Life

Much of what is known of Charlemagne's life comes from his biographer, Einhard, who wrote a Vita Caroli Magni (or Vita Karoli Magni), the Life of Charlemagne.

Early life

Charlemagne was the eldest child of Pippin the Short (714 – 24 September 768, reigned from 751) and his wife Bertrada of Laon (720 – 12 July 783), daughter of Caribert of Laon and Bertrada of Cologne. The reliable records name only Carloman and Gisela as his younger siblings. Later accounts, however, indicate that Redburga, wife of King Egbert of Wessex, might have been his sister (or sister-in-law or niece), and the legendary material makes him Roland's maternal uncle through Lady Bertha.

Einhard says of the early life of Charles:

- It would be folly, I think, to write a word concerning Charles' birth and infancy, or even his boyhood, for nothing has ever been written on the subject, and there is no one alive now who can give information on it. Accordingly, I determined to pass that by as unknown, and to proceed at once to treat of his character, his deed, and such other facts of his life as are worth telling and setting forth, and shall first give an account of his deed at home and abroad, then of his character and pursuits, and lastly of his administration and death, omitting nothing worth knowing or necessary to know.

This article follows that general format.

On the death of Pippin, the kingdom of the Franks was divided—following tradition—between Charlemagne and Carloman. Charles took the outer parts of the kingdom, bordering on the sea, namely Neustria, western Aquitaine, and the northern parts of Austrasia, while Carloman retained the inner parts: southern Austrasia, Septimania, eastern Aquitaine, Burgundy, Provence, and Swabia, lands bordering on Italy. Perhaps Pippin regarded Charlemagne as the better warrior, but Carloman may have regarded himself as the more deserving son, being the son, not of a mayor of the palace, but of a king.

Joint rule

On 9 October, immediately after the funeral of their father, both the kings withdrew from Saint Denis to be proclaimed by their nobles and consecrated by the bishops, Charlemagne in Noyon and Carloman in Soissons.

The first event of the brothers' reign was the rising of the Aquitainians and Gascons, in 769, in that territory split between the two kings. Pippin had killed in war Waifer, Duke of Aquitaine. Now, one Hunald led the Aquitainians as far north as Angoulême. Charlemagne met Carloman, but Carloman refused to participate and returned to Burgundy. Charlemagne went to war, leading an army to Bordeaux, where he set up a camp at Fronsac. Hunold was forced to flee to the court of Duke Lupus II of Gascony. Lupus, fearing Charlemagne, turned Hunold over in exchange for peace. He was put in a monastery. Aquitaine was finally fully subdued by the Franks.

The brothers maintained lukewarm relations with the assistance of their mother Bertrada, but Charlemagne signed a treaty with Duke Tassilo III of Bavaria and married Gerperga, daughter of King Desiderius of the Lombards, in order to surround Carloman with his own allies. Though Pope Stephen III first opposed the marriage with the Lombard princess, he would have little to fear of a Frankish-Lombard alliance in a few months.

Charlemagne repudiated his wife and quickly married another, a 13-year-old Swabian named Hildegard. The repudiated Gerperga returned to her father's court at Pavia. The Lombard's wrath was now aroused and he would gladly have allied with Carloman to defeat Charles. But before war could break out, Carloman died on 5 December 771. Carloman's wife Gerberga (often confused by contemporary historians with Charlemagne's former wife, who probably shared her name) fled to Desiderius' court with her sons for protection. This action is usually considered either a sign of Charlemagne's enmity or Gerberga's confusion.

Conquest of Lombardy

At the succession of Pope Hadrian I in 772, he demanded the return of certain cities in the former exarchate of Ravenna as in accordance with a promise of Desiderius' succession. Desiderius instead took over certain papal cities and invaded the Pentapolis, heading for Rome. Hadrian sent embassies to Charlemagne in autumn requesting he enforce the policies of his father, Pippin. Desiderius sent his own embassies denying the pope's charges. The embassies both met at Thionville and Charlemagne upheld the pope's side. Charlemagne promptly demanded what the pope had demanded and Desiderius promptly swore never to comply. The invasion was not short in coming. Charlemagne and his uncle Bernard crossed the Alps in 773 and chased the Lombards back to Pavia, which they then besieged. Charlemagne temporarily left the siege to deal with Adelchis, son of Desiderius, who was raising an army at Verona. The young prince was chased to the Adriatic littoral and he fled to Constantinople to plead for assistance from Constantine V Copronymus, who was waging war with the Bulgars.

The siege lasted until the spring of 774, when Charlemagne visited the pope in Rome. There he confirmed his father's grants of land, with some later chronicles claiming—falsely—that he also expanded them, granting Tuscany, Emilia, Venice, and Corsica. The pope granted him the title patrician. He then returned to Pavia, where the Lombards were on the verge of surrendering.

In return for their lives, the Lombards surrendered and opened the gates in early summer. Desiderius was sent to the abbey of Corbie and his son Adelchis died in Constantinople a patrician. Charles, unusually, had himself crowned with the Iron Crown and made the magnates of Lombardy do homage to him at Pavia. Only Duke Arechis II of Benevento refused to submit and proclaimed independence. Charlemagne was now master of Italy as king of the Lombards. He left Italy with a garrison in Pavia and few Frankish counts in place that very year.

There was still instability, however, in Italy. In 776, Dukes Hrodgaud of Friuli and Gisulf of Spoleto rebelled. Charlemagne whisked back from Saxony and defeated the duke of Friuli in battle. The duke was slain. The duke of Spoleto signed a treaty. Their co-conspirator, Arechis, was not subdued and Adelchis, their candidate in Byzantium, never left that city. Northern Italy was now faithfully his.

Saxon campaigns

Charlemagne was engaged in almost constant battle throughout his reign, with his legendary sword Joyeuse in hand. After thirty years of war and eighteen battles—the Saxon Wars—he conquered Saxonia and proceeded to convert the conquered to Roman Catholicism, using force where necessary.

The Saxons were divided into four subgroups in four regions. Nearest to Austrasia was Westphalia and furthest away was Eastphalia. In between these two kingdoms was that of Engria and north of these three, at the base of the Jutland peninsula, was Nordalbingia.

In his first campaign, Charlemagne forced the Engrians in 773 to submit and cut down the pagan holy pillar Irminsul near Paderborn. The campaign was cut short by his first expedition to Italy. He returned in the year 775, marching through Westphalia and conquering the Saxon fort of Sigiburg. He then crossed Engria, where he defeated the Saxons again. Finally, in Eastphalia, he defeated a Saxon force, and its leader Hessi converted to Christianity. He returned through Westphalia, leaving encampments at Sigiburg and Eresburg, which had, up until then, been important Saxon bastions. All Saxony but Nordalbingia was under his control, but Saxon resistance had not ended.

Following his campaign in Italy subjugating the dukes of Friuli and Spoleto, Charlemagne returned very rapidly to Saxony in 776, where a rebellion had destroyed his fortress at Eresburg. The Saxons were once again brought to heel, but their main leader, duke Widukind, managed to escape to Denmark, home of his wife. Charlemagne built a new camp at Karlstadt. In 777, he called a national diet at Paderborn to integrate Saxony fully into the Frankish kingdom. Many Saxons were baptised.

In the summer of 779, he again invaded Saxony and reconquered Eastphalia, Engria, and Westphalia. At a diet near Lippe, he divided the land into missionary districts and himself assisted in several mass baptisms (780). He then returned to Italy and, for the first time, there was no immediate Saxon revolt. From 780 to 782, the land had peace.

He returned in 782 to Saxony and instituted a code of law and appointed counts, both Saxon and Frank. The laws were draconian on religious issues, and the native traditional religion was gravely threatened. This stirred a renewal of the old conflict. That year, in autumn, Widukind returned and led a new revolt, which resulted in several assaults on the church. In response, at Verden in Lower Saxony, Charlemagne allegedly ordered the beheading of 4,500 Saxons who had been caught practising paganism after converting to Christianity, known as the Bloody Verdict of Verden or Massacre of Verden. The massacre, which modern research has not been able to confirm, triggered two years of renewed bloody warfare (783-785). During this war the Frisians were also finally subdued and a large part of their fleet was burned. The war ended with Widukind accepting baptism.

Thereafter, the Saxons maintained the peace for seven years, but in 792 the Westphalians once again rose against their conquerors. The Eastphalians and Nordalbingians joined them in 793, but the insurrection did not catch on and was put down by 794. An Engrian rebellion followed in 796, but Charlemagne's personal presence and the presence of loyal Christian Saxons and Slavs quickly crushed it. The last insurrection of the independence-minded people occurred in 804, more than thirty years after Charlemagne's first campaign against them. This time, the most unruly of them, the Nordalbingians, found themselves effectively disempowered from rebellion. According to Einhard:

- The war that had lasted so many years was at length ended by their acceding to the terms offered by the King; which were renunciation of their national religious customs and the worship of devils, acceptance of the sacraments of the Christian faith and religion, and union with the Franks to form one people.

Spanish campaign

To the Diet of Paderborn had come representatives of the Muslim rulers of Gerona, Barcelona, and Huesca. Their masters had been cornered in the Iberian peninsula by Abd ar-Rahman I, the Umayyad emir of Córdoba. The Moorish rulers offered their homage to the great king of the Franks in return for military support. Seeing an opportunity to extend Christendom and his own power and believing the Saxons to be a fully conquered nation, he agreed to go to Spain.

In 778, he led the Neustrian army across the Western Pyrenees, while the Austrasians, Lombards, and Burgundians passed over the Eastern Pyrenees. The armies met at Zaragoza and received the homage of Soloman ibn al-Arabi and Kasmin ibn Yusuf, the foreign rulers. Zaragoza did not fall soon enough for Charles, however. Indeed, Charlemagne was facing the toughest battle of his career and, in fear of losing, he decided to retreat and head home. He could not trust the Moors, nor the Basques, whom he had subdued by conquering Pamplona. He turned to leave Iberia, but as he was passing through the Pass of Roncesvalles one of the most famous events of his long reign occurred. The Basques fell on his rearguard and baggage train, utterly destroying it. The Battle of Roncevaux Pass, less a battle than a mere skirmish, left many famous dead: among which were the seneschal Eggihard, the count of the palace Anselm, and the warden of the Breton March, Roland, inspiring the subsequent creation of the Song of Roland (Chanson de Roland). Thus ended the Spanish campaign in complete disaster.

Charles and his children

During the first peace of any substantial length (780–782), Charles began to appoint his sons to positions of authority within the realm, in the tradition of the kings and mayors of the past. In 780, he had disinherited his eldest son, Pippin the Hunchback, because the young man had joined a rebellion against him. According to Charlemagne's biographer, Einhard, Pippin had been duped, through flattery, into joining a rebellion of nobles who pretended to despise Charles' treatment of Himiltrude, Pippin's mother, in 770. Charles renamed his son Carloman as Pippin to keep the name alive in the dynasty. In 781, he made his oldest three sons kings. The eldest, Charles, received the kingdom of Neustria, containing the regions of Anjou, Maine, and Touraine. The second eldest, Pippin, was made king of Italy, taking the Iron Crown which his father had first worn in 774. His third eldest son, Louis, became king of Aquitaine. He tried to make his sons a true Neustrian, Italian, and Aquitainian and he gave their regents some control of their subkingdoms, but real power was always in his hands, though he intended each to inherit their realm some day.

The sons fought many wars on behalf of their father when they came of age. Charles was mostly preoccupied with the Bretons, whose border he shared and who insurrected on at least two occasions and were easily put down, but he was also sent against the Saxons on multiple occasions. In 805 and 806, he was sent into the Böhmerwald (modern Bohemia) to deal with the Slavs living there (Czechs). He subjected them to Frankish authority and devastated the valley of the Elbe, forcing a tribute on them. Pippin had to hold the Avar and Beneventan borders, but also fought the Slavs to his north. He was uniquely poised to fight the Byzantine Empire when finally that conflict arose after Charlemagne's imperial coronation and a Venetian rebellion. Finally, Louis was in charge of the Spanish March and also went to southern Italy to fight the duke of Benevento on at least one occasion. He took Barcelona in a great siege in the year 797 (see below).

It is difficult to understand Charlemagne's attitude toward his daughters. None of them contracted a sacramental marriage. This may have been an attempt to control the number of potential alliances. Charlemagne certainly refused to believe the stories (mostly true) of their wild behaviour. After his death the surviving daughters entered or were forced to enter nunneries by their own brother, the pious Louis. At least one of them, Bertha, had a recognised relationship, if not a marriage, with Angilbert, a member of Charlemagne's court circle.

During the Saxon peace

In 787, Charlemagne directed his attention towards Benevento, where Arechis was reigning independently. He besieged Salerno and Arechis submitted to vassalage. However, with his death in 792, Benevento again proclaimed independence under his son Grimoald III. Grimoald was attacked by armies of Charles' or his sons' many times, but Charlemagne himself never returned to the Mezzogiorno and Grimoald never was forced to surrender to Frankish suzerainty.

In 788, Charlemagne turned his attention to Bavaria. He claimed Tassilo was an unfit ruler on account of his oath-breaking. The charges were trumped up, but Tassilo was deposed anyway and put in the monastery of Jumièges. In 794, he was made to renounce any claim to Bavaria for himself and his family (the Agilolfings) at the synod of Frankfurt. Bavaria was subdivided into Frankish counties, like Saxony.

In 789, in recognition of his new pagan neighbours, the Slavs, Charlemagne marched an Austrasian-Saxon army across the Elbe into Abotrite territory. The Slavs immediately submitted under their leader Witzin. He then accepted the surrender of the Wiltzes under Dragovit and demanded many hostages and the permission to send, unmolested, missionaries into the pagan region. The army marched to the Baltic before turning around and marching to the Rhine with much booty and no harassment. The tributary Slavs became loyal allies. In 795, the peace broken by the Saxons, the Abotrites and Wiltzes rose in arms with their new master against the Saxons. Witzin died in battle and Charlemagne avenged him by harrying the Eastphalians on the Elbe. Thrasuco, his successor, led his men to conquest over the Nordalbingians and handed their leaders over to Charlemagne, who greatly honoured him. The Abotrites remained loyal until Charles' death and fought later against the Danes.

Avar campaigns

In 788, the Avars, a pagan Asian horde which had settled down in what is today Hungary (Einhard called them Huns), invaded Friuli and Bavaria. Charles was preoccupied until 790 with other things, but in that year, he marched down the Danube into their territory and ravaged it to the Raab. Then, a Lombard army under Pippin marched into the Drava valley and ravaged Pannonia. The campaigns would have continued if the Saxons had not revolted again in 792, breaking seven years of peace.

For the next two years, Charles was occupied with the Slavs against the Saxons. Pippin and Duke Eric of Friuli continued, however, to assault the Avars' ring-shaped strongholds. The great Ring of the Avars, their capital fortress, was taken twice. The booty was sent to Charlemagne at his capital, Aachen, and redistributed to all his followers and even to foreign rulers, including King Offa of Mercia. Soon the Avar tuduns had thrown in the towel and travelled to Aachen to subject themselves to Charlemagne as vassals and Christians. This Charlemagne accepted and sent one native chief, baptised Abraham, back to Avaria with the ancient title of khagan. Abraham kept his people in line, but in 800 the Bulgarians under Krum had swept the Avar state away. In the 10th century, the Magyars settled the Pannonian plain and presented a new threat to Charlemagne's descendants.

Charlemagne also directed his attention to the Slavs to the south of the Avar khaganate: the Carantanians and Slovenes. These people were subdued by the Lombards and Bavarii and made tributaries, but never incorporated into the Frankish state.

The Saracens and Spain

The conquest of Italy brought Charlemagne in contact with the Saracens who, at the time, controlled the Mediterranean. Pippin, his son, was much occupied with Saracens in Italy. Charlemagne conquered Corsica and Sardinia at an unknown date and in 799 the Balearic Islands. The islands were often attacked by Saracen pirates, but the counts of Genoa and Tuscany (Boniface) kept them at bay with large fleets until the end of Charlemagne's reign. Charlemagne even had contact with the caliphal court in Baghdad. In 797 (or possibly 801), the caliph of Baghdad, Harun al-Rashid, presented Charlemagne with an Asian elephant named Abul-Abbas and a mechanical clock, out of which came a mechanical bird to announce the hours.

In Hispania, the struggle against the Moors continued unabated throughout the latter half of his reign. His son Louis was in charge of the Spanish border. In 785, his men captured Gerona permanently and extended Frankish control into the Catalan littoral for the duration of Charlemagne's reign (and much longer, it remained nominally Frankish until the Treaty of Corbeil in 1258). The Muslim chiefs in the northeast of Spain were constantly revolting against Cordoban authority and they often turned to the Franks for help. The Frankish border was slowly extended until 795, when Gerona, Cardona, Ausona, and Urgel were united into the new Spanish March, within the old duchy of Septimania.

In 797, Barcelona, the greatest city of the region, fell to the Franks when Zeid, its governor, rebelled against Córdoba and, failing, handed it to them. The Umayyad authority recaptured it in 799. However, Louis of Aquitaine marched the entire army of his kingdom over the Pyrenees and besieged it for two years, wintering there from 800 to 801, when it capitulated. The Franks continued to press forwards against the emir. They took Tarragona in 809 and Tortosa in 811. The last conquest brought them to the mouth of the Ebro and gave them raiding access to Valencia, prompting the Emir al-Hakam I to recognise their conquests in 812.

Imperator

Matters of Charlemagne's reign came to a head in late 800. In 799, Pope Leo III had been mistreated by the Romans, who tried to put out his eyes and tear out his tongue. He was deposed and put in a monastery. Charlemagne, advised by Alcuin of York, refused to recognise the deposition. He travelled to Rome in November 800 and held a council on December 1. On December 23, Leo swore an oath of innocence. At Mass, on Christmas Day (December 25), the pope crowned Charlemagne Imperator Romanorum (Emperor of the Romans) in Saint Peter's Basilica. Einhard says that Charlemagne was ignorant of the pope's intent and did not want any such coronation:

- he at first had such an aversion that he declared that he would not have set foot in the Church the day that they were conferred, although it was a great feast-day, if he could have foreseen the design of the Pope.

Charlemagne thus became the renewer of the Western Roman Empire, which had expired in 476. To avoid frictions with the Byzantine Emperor, Charles later styled himself, not Imperator Romanorum (a title reserved for the Byzantine emperor), but rather Imperator Romanum gubernans Imperium (emperor ruling the Roman Empire).

The iconoclasm of the Isaurian Dynasty and resulting religious conflicts with the Empress Irene, sitting on the throne in Constantinople in 800, were probably the chief causes of the pope's desire to formally resurrect the Roman imperial title in the West. He also most certainly desired to increase the influence of the papacy, honour his saviour Charlemagne, and solve the constitutional issues then most troubling to European jurists in an era when Rome was not in the hands of an emperor. Thus, Charlemagne's assumption of the title of Augustus, Constantine, and Justinian was not an usurpation in the eyes of the Franks or Italians. It was though in Byzantium, where it was protested by Irene and the usurper Nicephorus I — neither of whom had any great effect in enforcing their protests.

The Byzantines, however, still held several territories in Italy: Venice (what was left of the Exarchate of Ravenna), Reggio (Calabria, the toe), Brindisi (Apulia, the heel), and Naples (the Ducatus Neapolitanus). These regions remained outside of Frankish hands until 804, when the Venetians, torn by infighting, transferred their allegiance to the Iron Crown of Pippin, Charles' son. The Pax Nicephori ended. Nicephorus ravaged the coasts with a fleet and the only instance of war between Constantinople and Aachen, as it was, began. It lasted until 810, when the pro-Byzantine party in Venice gave their city back to the emperor in Byzantium and the two emperors of Europe made peace. Charlemagne received the Istrian peninsula and in 812 Emperor Michael I Rhangabes recognised his title.

Danish attacks

After the conquest of Nordalbingia, the Frankish frontier was brought into contact with Scandinavia. The pagan Danes, "a race almost unknown to his ancestors, but destined to be only too well known to his sons" as Charles Oman eloquently described them, inhabiting the Jutland peninsula had heard many stories from Widukind and his allies who had taken refuge with them about the dangers of the Franks and the fury which their Christian king could direct against pagan neighbours. In 808, the king of the Danes, Godfred, built the vast Danevirke across the isthmus of Schleswig. This defence, last employed in the Danish-Prussian War of 1864, was at its beginning a 30 km long earthenwork rampart. The Danevirke protected Danish land and gave Godfred the opportunity to harass Frisia and Flanders with pirate raids. He also subdued the Frank-allied Wiltzes and fought the Abotrites. He invaded Frisia and joked of visiting Aachen, but was murdered before he could do any more, either by a Frankish assassin or by one of his own men. Godfred was succeeded by his nephew Hemming, and he concluded a peace with Charlemagne in late 811.

Death

In 813, Charlemagne called Louis the Pious, king of Aquitaine, his only surviving legitimate son, to his court. There he crowned him as his heir and sent him back to Aquitaine. He then spent the autumn hunting before returning to Aachen on 1 November. In January, he fell ill. He took to his bed on 22 January and as Einhard tells it:

- He died January twenty-eighth, the seventh day from the time that he took to his bed, at nine o'clock in the morning, after partaking of the holy communion, in the seventy-second year of his age and the forty-seventh of his reign.

When Charlemagne died in 814, he was buried in his own Cathedral at Aachen. He was succeeded by his surviving son, Louis, who had been crowned the previous year. His empire lasted only another generation in its entirety; its division, according to custom, between Louis's own sons after their father's death laid the foundation for the modern states of France and Germany.

Administration

As an administrator, Charlemagne stands out for his many reforms: monetary, governmental, military, and ecclesiastical.

Monetary reforms

Pursuing his father's reforms, Charlemagne did away with the monetary system based on the gold Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help). Both he and the Anglo-Saxon King Offa of Mercia took up the system set in place by Pippin. He set up a new standard, the Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) (from the Latin Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)]], the modern pound)—a unit of both money and weight—which was worth 20 sous (from the Latin Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), the modern shilling) or 240 Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) (from the Latin Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), the modern penny). During this period, the Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) and the Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) were counting units, only the Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) was a coin of the realm.

Charlemagne applied the system to much of the European continent, and Offa's standard was voluntarily adopted by much of England. After Charlemagne's death, continental coinage degraded and most of Europe resorted to using the continued high quality English coin until about 1100.

Education reforms

A part of Charlemagne's success as warrior and administrator can be traced to his admiration for learning. His reign and the era it ushered in are often referred to as the Carolingian Renaissance because of the flowering of scholarship, literature, art, and architecture which characterise it. Charlemagne, brought into contact with the culture and learning of other countries (especially Visigothic Spain, Anglo-Saxon England and Lombard Italy) due to his vast conquests, greatly increased the provision of monastic schools and scriptoria (centres for book-copying) in Francia. Most of the surviving works of classical Latin were copied and preserved by Carolingian scholars. Indeed, the earliest manuscripts available for many ancient texts are Carolingian. It is almost certain that a text which survived to the Carolingian age survives still. The pan-European nature of Charlemagne's influence is indicated by the origins of many of the men who worked for him: Alcuin, an Anglo-Saxon from York; Theodulf, a Visigoth, probably from Septimania; Paul the Deacon, Peter of Pisa and Paulinus of Aquileia, Lombards; and Angilbert, Angilramm, Einhard and Waldo of Reichenau, Franks.

Charlemagne took a serious interest in his and others' scholarship and had learned to read in his adulthood, although he never quite learned how to write, he used to keep a slate and stylus underneath his pillow, according to Einhard. His handwriting was bad, from which grew the legend that he could not write. Even learning to read was quite an achievement for kings at this time, most of whom were illiterate.

Writing reforms

During Charles' reign, the Roman half uncial script and its cursive version, which had given rise to various continental minuscule scripts, combined with features from the insular scripts that were being used in Irish and English monasteries. Carolingian minuscule was created partly under the patronage of Charlemagne. Alcuin of York, who ran the palace school and scriptorium at Aachen, was probably a chief influence in this. The revolutionary character of the Carolingian reform, however, can be over-emphasised; efforts at taming the crabbed Merovingian and Germanic hands had been underway before Alcuin arrived at Aachen. The new minuscule was disseminated first from Aachen, and later from the influential scriptorium at Tours, where Alcuin retired as an abbot.

Political reforms

Charlemagne engaged in many reforms of Frankish governance, but he continued also in many traditional practices, such as the division of the kingdom among sons, to name but the most obvious one.

Organisation

In the first year of his reign, Charlemagne went to Aachen (in French, Aix-la-Chapelle) for the first time. He began to build a palace twenty years later (788). The palace chapel, constructed in 796, later became Aachen Cathedral. Charlemagne spent most winters between 800 and his death (814) at Aachen, which he made the joint capital with Rome, in order to enjoy the hot springs. Charlemagne organised his empire into 350 counties, each led by an appointed count. Counts served as judges, administrators, and enforcers of capitularies. To enforce loyalty, he set up the system of missi dominici, meaning "envoys of the lord". In this system, one representative of the church and one representative of the emperor would head to the different counties every year and report back to Charlemagne on their status.

Imperial coronation

Historians have debated for centuries whether Charlemagne was aware of the Pope's intent to crown him Emperor prior to the coronation itself (Charlemagne declared that he would not have entered Saint Peter's had he known), but that debate has often obscured the more significant question of why the Pope granted the title and why Charlemagne chose to accept it once he did.

Roger Collins points out (Charlemagne, pg. 147) "that the motivation behind the acceptance of the imperial title was a romantic and antiquarian interest in reviving the Roman empire is highly unlikely." For one thing, such romance would not have appealed either to Franks or Roman Catholics at the turn of the ninth century, both of whom viewed the Classical heritage of the Roman Empire with distrust. The Franks took pride in having "fought against and thrown from their shoulders the heavy yoke of the Romans" and "from the knowledge gained in baptism, clothed in gold and precious stones the bodies of the holy martyrs whom the Romans had killed by fire, by the sword and by wild animals", as Pippin III described it in a law of 763 or 764 (Collins 151). Furthermore, the new title — carrying with it the risk that the new emperor would "make drastic changes to the traditional styles and procedures of government" or "concentrate his attentions on Italy or on Mediterranean concerns more generally" (Collins 149) — risked alienating the Frankish leadership.

For both the Pope and Charlemagne, the Roman Empire remained a significant power in European politics at this time, and continued to hold a substantial portion of Italy, with borders not very far south of the city of Rome itself — this is the empire historiography has labelled the Byzantine Empire, for its capital was Constantinople (ancient Byzantium) and its people and rulers were Greek; it was a thoroughly Hellenic state. Indeed, Charlemagne was usurping the prerogatives of the Roman Emperor in Constantinople simply by sitting in judgement over the Pope in the first place:

- By whom, however, could he be tried? Who, in other words, was qualified to pass judgement on the Vicar of Christ? In normal circumstances the only conceivable answer to that question would have been the Emperor at Constantinople; but the imperial throne was at this moment occupied by Irene. That the Empress was notorious for having blinded and murdered her own son was, in the minds of both Leo and Charles, almost immaterial: it was enough that she was a woman. The female sex was known to be incapable of governing, and by the old Salic tradition was debarred from doing so. As far as Western Europe was concerned, the Throne of the Emperors was vacant: Irene's claim to it was merely an additional proof, if any were needed, of the degradation into which the so-called Roman Empire had fallen. (John Julius Norwich, Byzantium: The Early Centuries, pg. 378)

For the Pope, then, there was "no living Emperor at the that time" (Norwich 379), though Henri Pirenne (Mohammed and Charlemagne, pg. 234n) disputes this saying that the coronation "was not in any sense explained by the fact that at this moment a woman was reigning in Constantinople." Nonetheless, the Pope took the extraordinary step of creating one. The papacy had for some years been in conflict with Irene's predecessors in Constantinople over a number of issues, chiefly the continued Byzantine adherence to the doctrine of iconoclasm, the destruction of Christian images. By bestowing the Imperial crown upon Charlemagne, the Pope arrogated to himself "the right to appoint ... the Emperor of the Romans, ... establishing the imperial crown as his own personal gift but simultaneously granting himself implicit superiority over the Emperor whom he had created." And "because the Byzantines had proved so unsatisfactory from every point of view—political, military and doctrinal—he would select a westerner: the one man who by his wisdom and statesmanship and the vastness of his dominions ... stood out head and shoulders above his contemporaries."

With Charlemagne's coronation, therefore, "the Roman Empire remained, so far as either of them were concerned, one and indivisible, with Charles as its Emperor", though there can have been "little doubt that the coronation, with all that it implied, would be furiously contested in Constantinople." (Norwich, Byzantium: The Apogee, pg. 3) How realistic either Charlemagne or the Pope felt it to be that the people of Constantinople would ever accept the King of the Franks as their Emperor, we cannot know; Alcuin speaks hopefully in his letters of an Imperium Christianum ("Christian Empire"), wherein, "just as the inhabitants of the had been united by a common Roman citizenship", presumably this new empire would be united by a common Christian faith (Collins 151), certainly this is the view of Pirenne when he says "Charles was the Emperor of the ecclesia as the Pope conceived it, of the Roman Church, regarded as the universal Church" (Pirenne 233).

What we do know, from the Byzantine chronicler Theophanes (Collins 153), is that Charlemagne's reaction to his coronation was to take the initial steps toward securing the Constantinopolitan throne by sending envoys of marriage to Irene, and that Irene reacted somewhat favorably to them. Only when the people of Constantinople reacted to Irene's failure to immediately rebuff the proposal by deposing her and replacing her with one of her ministers, Nicephorus I, did Charlemagne drop any ambitions toward the Byzantine throne and begin minimising his new Imperial title, and instead return to describing himself primarily as rex Francorum et Langobardum.

The title of emperor remained in his family for years to come, however, as brothers fought over who had the supremacy in the Frankish state. The papacy itself never forgot the title nor abandoned the right to bestow it. When the family of Charles ceased to produce worthy heirs, the pope gladly crowned whichever Italian magnate could best protect him from his local enemies. This devolution led, as could have been expected, to the dormancy of the title for almost forty years (924-962). Finally, in 962, in a radically different Europe from Charlemagne's, a new Roman Emperor was crowned in Rome by a grateful pope. This emperor, Otto the Great, brought the title into the hands the kings of Germany for almost a millennium, for it was to become the Holy Roman Empire, a true imperial successor to Charles, if not Augustus.

Divisio regnorum

In 806, Charlemagne first made provision for the traditional division of the empire on his death. For Charles the Younger he designated the imperial title, Austrasia and Neustria, Saxony, Burgundy, and Thuringia. To Pippin he gave Italy, Bavaria, and Swabia. Louis received Aquitaine, the Spanish March, and Provence. This division may have worked, but it was never to be tested. Pippin died in 810 and Charles in 811. Charlemagne redrew the map of Europe by giving all to Louis, save the Iron Crown, which went to Pippin's (illegitimate) son Bernard. There was no mention of the imperial title however, which has led to the suggestion that Charlemagne regarded the title as an honorary achievement which held no hereditary significance.

Cultural significance

Charlemagne, being a model knight as one of the Nine Worthies, enjoyed an important afterlife in European culture. One of the great medieval literary cycles, the Charlemagne cycle or the Matter of France, centres on the deeds of Charlemagne and his historical commander of the border with Brittany, Roland, and the paladins who are analogous to the knights of the Round Table or King Arthur's court. Their tales constitute the first chansons de geste.

Charlemagne himself was accorded sainthood inside the Holy Roman Empire after the twelfth century. His canonisation by Antipope Paschal III, to gain the favour of Frederick Barbarossa in 1165, was never recognised by the Holy See, which annulled all of Paschal's ordinances at the Third Lateran Council in 1179. However, he has been acknowledged as cultus confirmed.

In the Divine Comedy the spirit of Charlemagne appears to Dante in the Heaven of Mars, among the other "warriors of the faith".

It is frequently claimed by genealogists that all people with European ancestry alive today are probably descended from Charlemagne. However, only a small percentage can actually prove descent from him. Charlemagne's marriage and relationship politics and ethics did, however, result in a fairly large number of descendants, all of whom had far better life expectancies than is usually the case for children in that time period. They were married into houses of nobility and as a result of intermarriages many people of noble descent can indeed trace their ancestry back to Charlemagne.

Charlemagne is memorably quoted by Henry Jones (played by Sean Connery) in the film, Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade. Immediately after using his umbrella to induce a flock of pigeons to smash through the glass cockpit of a pursuing German fighter plane, Henry Jones remarks "I suddenly remembered my Charlemagne: 'Let my armies be the rocks and the trees and the birds in the sky'."

Family

Marriages and heirs

- His first wife was Himiltrude, married in 766. The marriage was never formally annulled. By her he had:

- Pippin the Hunchback (767-813)

- His second wife was Gerperga (often erroneously called Desiderata or Desideria), daughter of Desiderius, king of the Lombards, married in 768, annulled in 771.

- His third wife was Hildegard (757 or 758-783 or 784), married 771, died 784. By her he had:

- Charles the Younger (772 or 773-811), King of the Franks administering Neustria

- Adelaide (773 or 774-774)

- Carloman, renamed Pippin (773 or 777-810), king of Italy

- Rotrude (or Hruodrud) (777-810)

- Louis (778-840), twin of Lothair, King of the Franks since 781, administering Aquitaine during his father's lifetime, since 814 sole king and emperor Holy Roman Emperor

- Lothair (778-779 or 780), twin of Louis

- Bertha (779-823)

- Gisela (781-808)

- Hildegarde (782-783)

- His fourth wife was Fastrada, married 784, died 794. By her he had:

- Theodrada (b.784), abbess of Argenteuil

- Hiltrude (b.787)

- His fifth and favorite wife was Luitgard, married 794, died 800 childless.

Concubinages and illegitimate children

- His first known concubine was Gersuinda. By her he had:

- Adaltrude (b.774)

- His second known concubine was Madelgard. By her he had:

- Ruodhaid (775-810), abbess of Faremoutiers

- His third known concubine was Amaltrud of Vienne. By her he had:

- Alpaida (b.794)

- His fourth known concubine was Regina. By her he had:

- Drogo (801-855), bishop of Metz from 823

- Hugh (802-844), archchancellor of the Empire

- His fifth known concubine was Ethelind. By her he had:

- Theodoric (b.807)

| Charlemagne Carolingian DynastyBorn: 742 Died: 814 | ||

| Preceded byPippin the Younger | King of the Franks 768–814 (until 771 jointly with Carloman) |

Succeeded byCharles II |

| Preceded byDesiderius | King of the Lombards 774–814 |

Succeeded byPippin as King of Italy |

| New title | Holy Roman Emperor 800–814 |

Succeeded byLouis the Pious |

Notes

- His name in English, Charlemagne, is identical to the Old French form, which in turn comes from the Latin. The Modern French translation of Charles the Great is Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), which is used. In German, he is called Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), which means Charles the Great; likewise in Dutch, Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help). His name in other Romance languages, like Italian and Spanish Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), is derived from the Latin. In other Germanic languages and Slavic languages, it is usually a translation of Charles the Great ( Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)). Many of the Slavic languages took their word for king from the German name for Charlemagne, Karl: Czech Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), South Slavic (such as Slovenian or Serbo-Croatian) Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), Polish Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), etc.

- Contemporary Latin sometimes Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help).

- Pierre Riche, The Carolingians: A Family Who Forged Europe, University of Pennsylvania Press, 1993, ISBN 0812213424

- Oman, Charles. The Dark Ages 476–919. Rivingtons: London, 1914. Regards Charlemagne's grandsons as the first kings of France and Germany, which at the time comprised the whole of the Carolingian Empire save Italy.

- Original text of the salic law.

See also

- List of Frankish Kings

- Carolingians

- Carolingian script

- Carolingian Renaissance

- Chanson de Roland

- Matter of France

- Nine Worthies

- History of elephants in Europe

- Attila the Hun to Charlemagne, hypothetical genealogy

- Charlemagne to the Mughals, hypothetical genealogy

- Descendants of Charlemagne

Sources

- Einhard (1960) . The Life of Charlemagne. trans. Samuel Epes Turner. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 047206035X.

- Oman, Charles (1914). The Dark Ages, 476-918 (6th ed. ed.). London: Rivingtons.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - Painter, Sidney (1953). A History of the Middle Ages, 284-1500. New York: Knopf.

- Santosuosso, Antonio (2004). Barbarians, Marauders, and Infidels: The Ways of Medieval Warfare. Boulder, Colo.: Westview Press. ISBN 0813391539.

- Scholz, Bernhard Walter (1970). Carolingian Chronicles: Royal Frankish Annals and Nithard's Histories. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0472087908.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) Comprises the Annales regni Francorum and The History of the Sons of Louis the Pious.

Further reading

- Barbero, Alessandro (2004). Charlemagne: Father of a Continent. trans. Allan Cameron. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-23943-1.

- Becher, Matthias (2003). Charlemagne. trans. David S. Bachrach. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0300097964.

- Ganshof, F. L. (1971). The Carolingians and the Frankish Monarchy: Studies in Carolingian History. trans. Janet Sondheimer. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press. ISBN 0801406358.

- Langston, Aileen Lewers (1974). Pedigrees of Some of the Emperor Charlemagne's Descendants. Baltimore: Genealogical Pub. Co.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Pirenne, Henri (1939). Mohammed and Charlemagne. trans. Bernard Miall. New York: Norton.

- Wilson, Derek (2005). Charlemagne: The Great Adventure. London: Hutchinson. ISBN 0091794617.

External links

- Charlemagne Chronology

- The Life of Charlemagne by Einhard. At Medieval Sourcebook.

- Vita Karoli Magni by Einhard. Latin text at The Latin Library.

- A reconstructed portrait of Charlemagne, based on historical sources, in a contemporary style.

- House of Pepin: Genealogy of Charlemagne.

- Charlemagne At Find A Grave

- Stoyan

- The Sword of Charlemagne (myArmoury.com article)