This is an old revision of this page, as edited by 72.73.104.28 (talk) at 02:22, 6 November 2006 (→Origin of trials). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 02:22, 6 November 2006 by 72.73.104.28 (talk) (→Origin of trials)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)

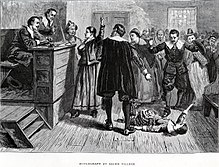

The Salem Witch Trials, which began in 1692 (also known as the Salem witch hunt and the Salem witchcraft episode), resulted in a number of convictions and executions for witchcraft in both Salem Village and Salem Town, Massachusetts. It was the result of a period of factional infighting and Puritan witch hysteria which led to the death of 20 people (14 women, 6 men) and the imprisonment of 150 more people.

Background

In 1692, Salem Village was torn by internal disputes between neighbors who disagreed about the choice of Samuel Parris as their first ordained minister. In January 1692, the residents of York, Maine, were attacked by Wabanaki Native Americans and many massacred or taken captive at the "Eastward" frontier of Maine, echoing the brutality of King Philip's War of 1675-76.

Increasing family size fueled disputes over land between neighbors and within families, especially on the frontier where the economy was based on farming. Changes in the weather or blights could easily wipe out a year's crop. A farm that could support an average-sized family could not support the many families of the next generation, prompting farmers to push further into the wilderness to find farmland - and encroach upon the indigenous people who already lived there. As the Puritans had vowed to create a theocracy in this new land, religious fervor added another tension to the mix: losses of crops, of livestock, and of children, as well as earthquakes and bad weather were typically attributed to the wrath of God. Within the Puritan faith, one's soul was considered predestined from birth as to whether they had been chosen for Heaven or condemned for Hell, and they constantly searched for hints, assuming God's pleasure and displeasure could be read in such signs given in the visible world. The invisible world was inhabited by God and the angels - including the Devil, a fallen angel, and to Puritans this invisible world was as real to them as the visible one around them.

The patriarchal beliefs that Puritans held in the community further stressed the atmosphere: women should be totally subservient to their men (he in public, she at home; he talking, she listening; he preaching, she hearing, etc.), that by nature a woman was more likely to enlist in the Devil's service than a man was (since women were not allowed to be preachers then they were more likely to sign themselves over to the Devil), and that women were naturally lustful.

In addition, the small town atmosphere made secrets very difficult to keep and people's opinions (positive or negative) about their neighbors were generally accepted as fact. In an age where the philosophy "children should be seen and not heard" reigned supreme, children were at the bottom of the social ladder. Toys and games were seen as idle and playing was discouraged, although girls had additional restrictions heaped upon them; boys were able to go hunting, fishing, exploring the forest, and often became apprentices to carpenters and smiths, while girls were trained from a tender age to spin yarn, cook, sew, weave, and to generally be servants to their husbands and mothers to their children.

Origin of trials

DO NOT CHANGE THIS!!!!

Legal Procedures

After someone concluded that a loss, illness or death had been caused by witchcraft, the accuser would enter a complaint against the alleged witch with the local magistrates.

If the complaint was deemed credible, the magistrates would have the person arrested and brought in for a public examination, essentially an interrogation, when the magistrates pressed the accused to confess.

If the magistrates at this local level were satisfied that the complaint was well-founded, the prisoner was handed over to be dealt with by a superior court. In 1692, the magistrates opted to wait for the arrival of the new charter and governor, who would establish a Court of Oyer and Terminer to handle these cases.

The next step, at the superior court level, was to summon witnesses before a grand jury. A person could be indicted on charges of afflicting with witchcraft, or for making an unlawful covenant with the Devil. Once indicted, the defendant went to trial, sometimes on the same day, as in the case of the first person indicted and tried on June 2, Bridget Bishop, who was executed on June 10, 1692.

There were four execution dates, with one person executed on June 10, 1692, five executed on July 19, 1692, another five executed on August 19, 1692 (Susannah Martin, John Willard, George Burroughs, George Jacobs Sr., and John Proctor), and eight on September 22, 1692 (Mary Esty, Martha Cory, Ann Pudeator, Samuel Wardwell, Mary Parker, Alice Parker, Wilmot Redd, and Margaret Scott). Several others, including Elizabeth (Bassett) Proctor and Abigail Faulkner were convicted but given temporary reprieves because they were pregnant (Chronology). Though convicted, they would not be hanged until they had given birth (Chronology). Five other women were convicted in 1692, but sentence was never carried out: Ann Foster (who later died in prison), her daughter Mary Lacy Sr., Abigail Hobbs, Dorcas Hoar, and Mary Bradbury.

Giles Corey, an 80-year-old farmer from the southeast end of Salem called Salem Farms, refused to enter a plea when he came to trial in September. The law provided for the application of a form of torture called peine fort et dure, in which the victim was slowly crushed by piling stones on a board that was laid upon the victim's body. After two days of peine fort et dure, Corey died without entering a plea (Boyer 8). Though his refusal to plead is often explained as a way of preventing his possessions from being confiscated by the state, this is not true; the possessions of convicted witches were often confiscated, and the possessions of persons accused but not convicted were confiscated before a trial, as in the case of Corey's neighbor John Proctor and the wealthy English's of Salem Town. Some historians hypothesize that Giles Corey's personal character, a stubborn and lawsuit-prone old man who knew he was going to be convicted regardless, led to his recalcitrance (Boyer 8).

Sadly, not even in death were the accused witches granted peace or respect. As convicted witches, Rebecca Nurse and Martha Corey had been excommunicated from their churches and none were given proper burial. As soon as the bodies of the accused people were cut down from the trees, they were thrown into a shallow grave and the crowd would then leave. Oral history claims that the families of the dead reclaimed their bodies after dark and buried them in unmarked graves on family property. The record books of the time do not mention the deaths of any of those executed.

Closure

The Reverend Francis Dane led the opposition and supported the accused. He petitioned the Governor and General Court, condemning the trials due to unfounded accusations. The last witch trials took place in May of 1693, although people already found not guilty of witchcraft were not released until they paid their jailers' fees. On October 3, 1692, Increase Mather published "Cases of Conscience Concerning Evil Spirits." In it, Increase Mather stated "It were better that Ten Suspected Witches should escape, than that one Innocent Person should be Condemned." After another trial was conducted, all those in jail were set free in May of 1693 (this amnesty is what saved Elizabeth Proctor).

Many descendants of the people who were wrongfully convicted still sought closure. Numerous petitions were filed between 1692 and 1711, demanding monetary restitution to those wrongly imprisoned.

The Massachusetts House of Representatives finally passed a bill disallowing spectral evidence. However, they only gave reversal of attainder for those who had filed petitions. This applied to only three people, who had been convicted but not executed: Abigail Faulkner Sr., Elizabeth Proctor, and Sarah Wardwell.

In 1704, another petition was filed, requesting a more equitable settlement for those wrongly accused. In 1709, the General Court received a request to take action on this proposal. In May 1709, 22 people who had been convicted of witchcraft, or whose parents had been convicted of witchcraft, presented the government with a petition in which they demanded both a reversal of attainder and compensation for financial losses.

In 1706, Ann Putnam, one of the most active accusers, was the only girl to offer a written apology. She claimed that she had not acted out of malice, but was being deluded by Satan into denouncing innocent people, and mentioned Rebecca Nurse in particular. In 1712 the pastor who had cast Rebecca out of the church formally cancelled the excommunication.

On October 17, 1711, the General Court passed a bill reversing the judgment against the 22 people listed in the 1709 petition. There were still an additional 7 people who had been convicted, but had not signed the petition. There was no reversal of attainder for them.

On December 17, 1711, monetary compensation was finally awarded to the 22 people in the 1709 petition. 578 pounds 12 shillings were authorized to be divided among the survivors and relatives of those accused. Most of the accounts were settled within a year. 150 pounds were awarded to the Proctor family for John and Elizabeth. The Proctor family received much more money from the Massachusetts General Court than most families of accused witches.

By 1957, not all the condemned had been exonerated. Descendants of those falsely accused demanded the General Court clear the names of their family members. An act was passed pronouncing the innocence of those accused -- however, it only listed Ann Pudeator by name, and the others as "certain other persons", still failing to include all names of those convicted.

In 1992, The Danvers Tercentenial Committee persuaded the Massachusetts House of Representatives to issue a resolution honoring those who had died. After much convincing and hard work by Salem school teacher Paula Keene, Representatives J. Michael Ruane and Paul Tirone and a few others, the names of all those not previously listed were added to this resolution. When it was finally signed on October 31, 2001 by Governor Jane Swift, more than 300 years later, all were finally proclaimed innocent.

Possible Explanations of the "Possessed"

It is not widely believed any longer that the girls were actually possessed by the devil. Some academics believe that the accusers were motivated by jealousy or spite and their behavior was an act. Contemporaneous to the witch trials was the Glorious Revolution in England; the colony of Massachusetts was without a charter or governor, leading to political strife and uncertainty. Other theories posit that they were afflicted by hysteria, a form of mental illness.

In 1976, graduate student Linnda Caporael published an article in Science magazine, making the claim that the hallucinations of the afflicted girls could possibly have been the result of ingesting rye bread that had been made with moldy grain. "Ergot of Rye is a plant disease that is caused by the fungus Claviceps purpurea. It is the ergot stage of the fungus that contains a similar chemical compounds to a popular but illegal drug of the counter-culture of the 1960s, LSD. Convulsive ergotism causes nervous dysfunction, which Caporael claims are similar to many of the physical symptoms of those alleged to be afflicted by witchcraft. Within 7 months, a refutation of this theory was published in the same magazine by Spanos and Gottlieb, arguing, among other things, that if the poison was in the food supply, the symptoms would have occurred on a house-by-house basis, and that biological symptoms do not stop and start on cue and simultaneously in a group of those so afflicted, as described by the witnesses to the afflictions.

In her book A Fever in Salem, Laurie Winn Carlson offers an alternative theory. She believes that those afflicted in Salem, who claimed to have been bewitched, suffered from encephalitis lethargica, a disease whose symptoms match some of what was reported in Salem and could have been spread by birds and other animals (Aronson).

It has also been suggested that the girls could have had Huntington's Chorea, carriers of which have been traced to be among the colonists that settled in that area , but no serious historian of this episode today (Mary Beth Norton, Bernard Rosenthal, Marilynne K. Roach and others) gives any of these medical explanations any serious consideration.

While the theory of disease or mental illness could be possible, the fact that as soon as the newly instated Governor William Phips' wife was indicated, the situation slowed and eventually stopped. This logic points to the possibility that the witch trials were more social and political than due to illness.

Salem Today

"With one of the highest concentrations of historic sites, museums, cultural activities, fine dining and shopping in Massachusetts, Salem is America's Bewitching Seaport with a little history in every step" (Destination Salem). Today the Salem Witchcraft Trials have become the basis of a money-making tourist industry in Salem. Witch shops are seen all over the community. Museums promise glimpses of the supernatural. Gift shops sell everything from Witch City shirts to Buddhism in a can. Tourists are treated to informational exhibits and programs.

Connected to Boston by train and bus, Salem's 38,000 residents and its one-million visitors are able to easily enjoy the best of both Salem and Boston.

In recent times, "historians see both sides of Salem" (Aronson). Still to this day, there is not a solid explanation for what occurred in the Salem Witch Trials in the 1600s.

The Salem Witch Trials in Literature

The Salem Witch Trials have provided the basis for two of America's great works of drama, Giles Corey in Henry Wadsworth Longfellow's New England Tragedies and Arthur Miller's classic play The Crucible. Both plays deal with the problem of presumed guilt and both follow a single character from his accusation to his eventual condemnation. Longfellow's play, which follows the form of a Shakespearean tragedy, is a commentary on the attitudes prevalent in 19th-century New England. Miller's play is a commentary on the actions of the House Committee on Unamerican Activities and Senator Joe McCarthy. Lois the Witch by Elizabeth Gaskell is a novella based on the Salem witch hunts and shows how jealousy and sexual desire can lead to hysteria. She was inspired by the story of Rebecca Nurse whose accusation, trial and execution are described in Lectures on Witchcraft, by Charles Upham, the Unitarian minister in Salem in the 1830s.

Footnotes

- See The Complaint v. Elizabeth Procter & Sarah Cloyce for an example of one of the primary sources of this type.

- The Arrest Warrant of Rebecca Nurse

- The Examination of Martha Corey

- For an example: Summons for Witnesses v. Rebecca Nurse

- Indictment of Sarah Good for Afflicting Sarah Vibber

- Indictment of Abigail Hobbs for Covenanting

- The Death Warrant of Bridget Bishop

- Death Warrant for Sarah Good, Rebecca Nurse, Susannah Martin, Elizabeth How & Sarah Wilds

- http://etext.virginia.edu/salem/witchcraft/archives/MA135/93.html

- Enders Robinson, The Devil Discovered, 2001 edition, preface, pp. xvi-xvii

References used

- Aronson, Marc. Witch-Hunt: Mysteries of the Salem Witch Trials. Simon and Schuster: 2003.

- Boyer, Paul, and Stephen Nissenbaum. Salem Possessed: The Social Origins of Witchcraft. MJF Books: 1974.

- "Chronology of Events Relating to the Salem Witchcraft Trials". 15 April 2006.

- "Ergot Theory". 3 April 2006.

- Linder, Douglas. "The Witchcraft Trials in Salem: A Commentary". 15 April 2006.

- "The Dead". 15 April 2006. <http://www.law.ukmc.edu/faculty/projects/ftrials/salem/ASAL_DE.HTM>

- "Salem Witch Trials Documentary Archive and Transcription Project". 15 August 2006

- "

The Salem News, “Documents Shed New Light On Witchcraft Trials”, By BETSY TAYLOR, news staff Danvers, Massachusetts

The History of the Town of Danvers, from it’s Earliest Settlement to 1848, by J.W. Hanson, copyright 1848, published by the author, printed at the Courier Office, Danvers, Massachusetts

House of John Proctor, Witchcraft Martyr, 1692, by William P. Upham, copyright 1904, Press of C.H. Shephard, Peabody, Massachusetts,

Puritan City, The Story of Salem, by Frances Win war, King County Library System 917.44, copyright 1938, Robert M. McBride & County, New York.

The Salem witchcraft papers : verbatim transcripts of the legal documents of the Salem witchcraft outbreak of 1692 / compiled and transcribed in 1938 by the Works Progress Administration, under the supervision of Archie N. Frost ; edited and with an introduction and index by Paul Boyer and Stephen Nissenbaum; Electronic Text Center, University of Virginia Library; pg. 662; Essex County Archives, Salem -- Witchcraft Vol. 1

The Founders of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, A Careful Research of the Earliest Records of Many of the Foremost Settlers of the New England Colony: Compiled From The Earliest Church and State Records, and Valuable Private Papers Retained by Descendants for Many Generations, by Sarah Saunders Smith, Press of the Sun Printing Company, 1897, Pittsfield Massachusetts

The Devil Discovered : Salem Witchcraft, 1692 by Enders A. Robinson

Salem Possessed: The Social Origins of Witchcraf by Paul Boyer

Chronicles of Old Salem, A History in Minature by Francis Diane Robotti

The Devil in Massachusetts, A Modern Enquiry Into the Salem Witch Trials, by Marion L. Starkey, King County Library System, copyright 1949, Anchor Books / Doubleday Books, New York

A Delusion of Satan: The Full Story of the Salem Witch Trials by Frances Hill

The Salem Witch Trials Reader by Frances Hill

The Witchcraft of Salem Village by Shirley Jackson

Salem Witchcraft; With an Account of Salem Village and a History of Opinions on Witchcraft and Kindred Subjects. by Charles W. Upham

The Devil Hath Been Raised: A Documentary History of the Salem Village Witchcraft Outbreak of March 1692 by Richard B. Trask

The Visionary Girls: Witchcraft in Salem Village by Marion Lena Starkey

The Salem Witch Trials, A Day by Day Chronicle of a Community Under Siege, by Marilynne K. Roach, copyright 2002, Taylor Trade Publishing, Lanham, Maryland.

Further reading

- Aronson, Marc. "Witch-Hunt: Mysteries of the Salem Witch Trials." Atheneum: New York. 2003.

- Boyer, Paul & Nissenbaum, Stephen. "Salem Possessed: The Social Origins of Witchcraft." Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA. 1974.

- Boyer, Paul & Nissenbaum, Stephen, eds.. "Salem-Village Witchcraft: A Documentary Record of Local Conflict in Colonial New England" Northeastern University Press: Boston, MA. 1972.

- Breslaw, Elaine G.. "Tituba, Reluctant Witch of Salem: Devilish Indians and Puritan Fantasies." NYU: New York. 1996.

- Brown, David C.. "A Guide to the Salem Witchcraft Hysteria of 1692." David C. Brown: Washington Crossing, PA. 1984.

- Demos, John. Entertaining Satan: Witchcraft and the Culture of Early New England. New York: Oxford University Press, 1982.

- Godbeer, Richard. "The Devil's Dominion: Magic and Religion in Early New England." Camridge University Press: New York. 1992.

- Hansen, Chadwick. "Witchcraft at Salem." Brazillier: New York. 1969.

- Hill, Frances. "A Delusion of Satan: The Full Story of the Salem Witch Trials." Doubleday: New York. 1995.

- Hoffer, Peter Charles. "The Salem Witchcraft Trials: A Legal History." University of Kansas: Lawrence, KS. 1997.

- Karlsen, Carol F. The Devil in the Shape of a Woman: Witchcraft in Colonial New England. New York: Vintage, 1987.

- Lasky, Kathryn. "Beyond the Burning Time." Point: New York, NY 1994

- Le Beau, Bryan, F.. "The Story of the Salem Witch Trials: `We Walked in Coulds and Could Not See Our Way.`" Prentice-Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ. 1998.

- Mappen, Marc, ed.. "Witches & Historians: Interpretations of Salem." 2nd Edition. Keiger: Malabar, FL. 1996.

- Miller, Arthur. "The Crucible — a play which implicitly compares McCarthyism to a witch-hunt".

- Norton, Mary Beth. In the Devil's Snare: The Salem Witchcraft Crisis of 1692. New York: Random House, 2002.

- Reis, Elizabeth. "Damned Women: Sinners and Witches in Puritan New England." Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY. 1997.

- Roach, Marilynne K. The Salem Witch Trials: A Day-To-Day Chronicle of a Community Under Siege. Cooper Square Press, 2002.

- Robinson, Enders A. "The Devil Discovered: Salem Witchcraft 1692." Hippocrene: New York. 1991.

- Robinson, Enders A.. "Salem Witchcraft and Hawthorne's House of the Seven Gables." Heritage Books: Bowie, MD. 1992.

- Rosenthal, Bernard. "Salem Story: Reading the Witch Trials of 1692." Cambridge University Press: New York. 1993.

- Sologuk, Sally. "Diseases Can Bewitch Durum Millers". Milling Journal. Second quarter 2005.

- Spanos, N. P., J. Gottlieb. "Ergots and Salem village witchcraft: A critical appraisal". Science: 194. 1390-1394:1976.

- Starkey, Marion L. The Devil in Massachusetts. Alfred A. Knopf: 1949.

- Trask, Richard B.. "`The Devil hath been raised`: A Documentary History of the Salem Village Witchcraft Outbreak of March 1692." Revised edition. Yeoman Press: Danvers, MA. 1997.

- Upham, Charles W.. "Salem Witchcraft." Reprint from the 1867 edition, in two volumes. Dover Publications: Mineola, NY. 2000.

- Weisman, Richard. "Witchcraft, Magic, and Religion in 17th-Century Massachusetts." University of Massachusetts Press: Amherst, MA. 1984.

- Wilson, Jennifer M.. Witch. Authorhouse, Feb. 2005.

- Wilson, Lori Lee. "The Salem Witch Trials." How History Is Invented series. Lerner: Minneapolis. 1997.

- Woolf, Alex. "Investigating History Mysteries". Heinemann Library: 2004.

- Wright, John Hardy. "Sorcery in Salem." Arcadia: Portsmouth, NH. 1999.

- "The 19th and 20th Centuries". Destination Salem. 12 Apr. 2006 .

See also

- The Crucible

- A Break with Charity

- Jury Nullification

- McCarthyism

- Red scare

- Spectral evidence

- Supernatural

- Torsåker witch trials

- Pendle witches

External links

- Salem Witchcraft Trials of 1692

- A documentary archive including original court papers on the trials, maps, interactive maps, biographies, and internal and external links to more resources.

- University of Virginia: Salem Witch Trials (includes former "Massachusetts Historical Society" link)

- "Diseases Can Bewitch Durum Millers" article about ergot-infected grains, ergotism and how it is prevented today.

- PBS Secrets of the Dead: "The Witches Curse" (concerning the Salem trials and ergot)

- Salem Witchcraft, Volumes I and II, by Charles Upham, 1867, fron Project Gutenberg

- Salem Witch Trials:The World Behind the Hysteria

- SalemWitchTrials.com essays, biographies of the accused and afflicted