This is an old revision of this page, as edited by PlyrStar93 (talk | contribs) at 17:09, 5 February 2019 (Reverted edits by Red Dragon 93 (talk) to last version by 137.161.255.13). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 17:09, 5 February 2019 by PlyrStar93 (talk | contribs) (Reverted edits by Red Dragon 93 (talk) to last version by 137.161.255.13)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) This article is about the festival observed on the traditional Chinese and Tibetan calendar. For the first day of the year observed on other lunar or lunisolar calendars, see Lunar New Year.| Chinese New Year | |

|---|---|

Fireworks are a classic element of Chinese New Year and Tibetans celebrate it with prayers, Tibetan traditional circle dance Fireworks are a classic element of Chinese New Year and Tibetans celebrate it with prayers, Tibetan traditional circle dance | |

| Also called | Spring Festival |

| Observed by | Tibetans and Chinese people worldwide |

| Type | Cultural, religious (Chinese folk religion, Buddhist, Confucian, Daoism) |

| Celebrations | Lion dances, dragon dances, fireworks, family gathering, family meal, visiting friends and relatives, giving red envelopes, decorating with chunlian couplets |

| Date | First day of the first month of the Chinese calendar (between 21 January and 20 February) |

| Frequency | Annual |

| Related to | Lantern Festival, which concludes the celebration of the Chinese New Year. Mongol New Year (Tsagaan Sar), Tibetan New Year (Losar), Japanese New Year (Shōgatsu), Korean New Year (Seollal), Vietnamese New Year (Tết) |

| Chinese New Year | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

"Chinese New Year (Lunar New Year)" in Traditional (top) and Simplified (bottom) Chinese characters "Chinese New Year (Lunar New Year)" in Traditional (top) and Simplified (bottom) Chinese characters | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 春節 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 春节 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | "Spring Festival" | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Chinese New Year is the Chinese festival that celebrates the beginning of a new year on the traditional Chinese calendar. The festival is usually referred to as the Spring Festival in mainland China, and is one of several Lunar New Years in Asia. Observances traditionally take place from the evening preceding the first day of the year to the Lantern Festival, held on the 15th day of the year. The first day of Chinese New Year begins on the new moon that appears between 21 January and 20 February. In 2019, the first day of the Chinese New Year was on Tuesday, 5 February, initiating the Year of the Pig.

Chinese New Year is a major holiday in Greater China and has strongly influenced lunar new year celebrations of China's neighbouring cultures, including the Korean New Year (seol), the Tết of Vietnam, and the Losar of Tibet. It is also celebrated worldwide in regions and countries with significant Overseas Chinese populations, including Singapore, Indonesia, Malaysia, Myanmar, Thailand, Cambodia, the Philippines, and Mauritius, as well as many in North America and Europe.

Chinese New Year is associated with several myths and customs. The festival was traditionally a time to honour deities as well as ancestors. Within China, regional customs and traditions concerning the celebration of the New Year vary widely, and the evening preceding Chinese New Year's Day is frequently regarded as an occasion for Chinese families to gather for the annual reunion dinner. It is also traditional for every family to thoroughly clean their house, in order to sweep away any ill-fortune and to make way for incoming good luck. Another custom is the decoration of windows and doors with red paper-cuts and couplets. Popular themes among these paper-cuts and couplets include that of good fortune or happiness, wealth, and longevity. Other activities include lighting firecrackers and giving money in red paper envelopes. For the northern regions of China, dumplings are featured prominently in meals celebrating the festival.

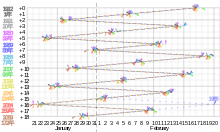

Dates in Chinese lunisolar calendar

The lunisolar Chinese calendar determines the date of Lunar New Year. The calendar is also used in countries that have been influenced by, or have relations with, China – such as Korea, Japan and Vietnam, though occasionally the date celebrated may differ by one day or even one moon cycle due to using a meridian based on a different capital city in a different time zone or different placements of intercalary months.

Chinese calendar defines the lunar month with winter solstice as the 11th month, which means that Chinese New Year usually falls on the second new moon after the winter solstice (rarely the third if an intercalary month intervenes). In more than 96% of the years, the Chinese New Year's Day is the closest new moon to lichun (Chinese: 立春; lit. start of spring) on 4 or 5 February, and the first new moon after Dahan (Chinese: 大寒; lit. major cold). In the Gregorian calendar, the Lunar New Year begins at the new moon that falls between 21 January and 20 February.

The Gregorian Calendar dates for Chinese New Year from 1912 to 2101 are below, along with the year's presiding animal zodiac and its Stem-branch. The traditional Chinese calendar follows a Metonic cycle, a system used by the modern Jewish Calendar, and returns to the same date in Gregorian calendar roughly. The names of the Earthly Branches have no English counterparts and are not the Chinese translations of the animals. Alongside the 12-year cycle of the animal zodiac there is a 10-year cycle of heavenly stems. Each of the ten heavenly stems is associated with one of the five elements of Chinese astrology, namely: Wood, Fire, Earth, Metal, and Water. The elements are rotated every two years while a yin and yang association alternates every year. The elements are thus distinguished: Yang Wood, Yin Wood, Yang Fire, Yin Fire, etc. These produce a combined cycle that repeats every 60 years. For example, the year of the Yang Fire Rat occurred in 1936 and in 1996, 60 years apart.

Many people inaccurately calculate their Chinese birth-year by converting it from their Gregorian birth-year. As the Chinese New Year starts in late January to mid-February, the previous Chinese year dates through 1 January until that day in the new Gregorian year, remaining unchanged from the previous Gregorian year. For example, the 1989 year of the Snake began on 6 February 1989. The year 1989 is generally aligned with the year of the Snake. However, the 1988 year of the Dragon officially ended on 5 February 1989. This means that anyone born from 1 January to 5 February 1989 was actually born in the year of the Dragon rather than the year of the Snake. Many online Chinese Sign calculators do not account for the non-alignment of the two calendars, using Gregorian-calendar years rather than official Chinese New Year dates.

One scheme of continuously numbered Chinese-calendar years assigns 4709 to the year beginning, 2011, but this is not universally accepted; the calendar is traditionally cyclical, not continuously numbered.

Although the Chinese calendar traditionally does not use continuously numbered years, outside China its years are sometimes numbered from the purported reign of the mythical Yellow Emperor in the 3rd millennium BCE. But at least three different years numbered 1 are now used by various scholars, making the year beginning CE 2015 the "Chinese year" 4712, 4713, or 4652.

| Gregorian | Date | Animal | Day of the week | Gregorian | Date | Animal | Day of the week | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2001 | 24 Jan | Snake | Wednesday | 2026 | 17 Feb | Horse | Tuesday | |

| 2002 | 12 Feb | Horse | Tuesday | 2027 | 6 Feb | Goat | Saturday | |

| 2003 | 1 Feb | Goat | Saturday | 2028 | 26 Jan | Monkey | Wednesday | |

| 2004 | 22 Jan | Monkey | Thursday | 2029 | 13 Feb | Rooster | Tuesday | |

| 2005 | 9 Feb | Rooster | Wednesday | 2030 | 3 Feb | Dog | Sunday | |

| 2006 | 29 Jan | Dog | Sunday | 2031 | 23 Jan | Pig | Thursday | |

| 2007 | 18 Feb | Pig | Sunday | 2032 | 11 Feb | Rat | Wednesday | |

| 2008 | 7 Feb | Rat/Mouse | Thursday | 2033 | 31 Jan | Ox | Monday | |

| 2009 | 26 Jan | Ox | Monday | 2034 | 19 Feb | Tiger | Sunday | |

| 2010 | 14 Feb | Tiger | Sunday | 2035 | 8 Feb | Rabbit | Thursday | |

| 2011 | 3 Feb | Rabbit | Thursday | 2036 | 28 Jan | Dragon | Monday | |

| 2012 | 23 Jan | Dragon | Monday | 2037 | 15 Feb | Snake | Sunday | |

| 2013 | 10 Feb | Snake | Sunday | 2038 | 4 Feb | Horse | Thursday | |

| 2014 | 31 Jan | Horse | Friday | 2039 | 24 Jan | Goat | Monday | |

| 2015 | 19 Feb | Goat | Thursday | 2040 | 12 Feb | Monkey | Sunday | |

| 2016 | 8 Feb | Monkey | Monday | 2041 | 1 Feb | Rooster | Friday | |

| 2017 | 28 Jan | Rooster | Saturday | 2042 | 22 Jan | Dog | Wednesday | |

| 2018 | 16 Feb | Dog | Friday | 2043 | 10 Feb | Pig | Tuesday | |

| 2019 | 5 Feb | Pig | Tuesday | 2044 | 30 Jan | Rat | Saturday | |

| 2020 | 25 Jan | Rat | Saturday | 2045 | 17 Feb | Ox | Friday | |

| 2021 | 12 Feb | Ox | Friday | 2046 | 6 Feb | Tiger | Tuesday | |

| 2022 | 1 Feb | Tiger | Tuesday | 2047 | 26 Jan | Rabbit | Saturday | |

| 2023 | 22 Jan | Rabbit | Sunday | 2048 | 14 Feb | Dragon | Friday | |

| 2024 | 10 Feb | Dragon | Saturday | 2049 | 2 Feb | Snake | Tuesday | |

| 2025 | 29 Jan | Snake | Wednesday | 2050 | 23 Jan | Horse | Sunday |

| Gregorian | Date | Animal | Day of the week | Gregorian | Date | Animal | Day of the week | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2051 | 11 Feb | Goat | Saturday | 2076 | 5 Feb | Monkey | Wednesday | |

| 2052 | 1 Feb | Monkey | Thursday | 2077 | 24 Jan | Rooster | Sunday | |

| 2053 | 19 Feb | Rooster | Wednesday | 2078 | 12 Feb | Dog | Saturday | |

| 2054 | 8 Feb | Dog | Sunday | 2079 | 2 Feb | Pig | Thursday | |

| 2055 | 28 Jan | Pig | Thursday | 2080 | 22 Jan | Rat | Monday | |

| 2056 | 15 Feb | Rat | Tuesday | 2081 | 9 Feb | Ox | Sunday | |

| 2057 | 4 Feb | Ox | Sunday | 2082 | 29 Jan | Tiger | Thursday | |

| 2058 | 24 Jan | Tiger | Thursday | 2083 | 17 Feb | Rabbit | Wednesday | |

| 2059 | 12 Feb | Rabbit | Wednesday | 2084 | 6 Feb | Dragon | Sunday | |

| 2060 | 2 Feb | Dragon | Monday | 2085 | 26 Jan | Snake | Friday | |

| 2061 | 21 Jan | Snake | Friday | 2086 | 14 Feb | Horse | Thursday | |

| 2062 | 9 Feb | Horse | Thursday | 2087 | 3 Feb | Goat | Monday | |

| 2063 | 29 Jan | Goat | Monday | 2088 | 24 Jan | Monkey | Saturday | |

| 2064 | 17 Feb | Monkey | Sunday | 2089 | 10 Feb | Rooster | Thursday | |

| 2065 | 5 Feb | Rooster | Thursday | 2090 | 30 Jan | Dog | Monday | |

| 2066 | 26 Jan | Dog | Tuesday | 2091 | 18 Feb | Pig | Sunday | |

| 2067 | 14 Feb | Pig | Monday | 2092 | 7 Feb | Rat | Thursday | |

| 2068 | 3 Feb | Rat | Friday | 2093 | 27 Jan | Ox | Tuesday | |

| 2069 | 23 Jan | Ox | Wednesday | 2094 | 15 Feb | Tiger | Monday | |

| 2070 | 11 Feb | Tiger | Tuesday | 2095 | 5 Feb | Rabbit | Saturday | |

| 2071 | 31 Jan | Rabbit | Saturday | 2096 | 25 Jan | Dragon | Wednesday | |

| 2072 | 19 Feb | Dragon | Friday | 2097 | 12 Feb | Snake | Tuesday | |

| 2073 | 7 Feb | Snake | Tuesday | 2098 | 1 Feb | Horse | Saturday | |

| 2074 | 27 Jan | Horse | Saturday | 2099 | 21 Jan | Goat | Wednesday | |

| 2075 | 15 Feb | Goat | Friday | 2100 | 9 Feb | Monkey | Tuesday |

| YearDate | 1-19AM | 20-38AM | 39-57AM | 58-76AM | 77-95AM | 96-114AM | 115-133AM | 134-152AM | 153-171AM | 172-190AM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1912–1930 | 1931–1949 | 1950–1968 | 1969–1987 | 1988–2006 | 2007–2025 | 2026–2044 | 2045–2063 | 2064–2082 | 2083–2101 | |

| 17 Feb | Rat Rénzǐ |

Goat Xīnwèi |

Tiger Gēngyín |

Rooster Jǐyǒu |

Dragon Wùchén |

Pig Dīnghaì + |

Horse Bǐngwǔ |

Ox Yǐchǒu |

Monkey Jiǎshēn |

Rabbit Guǐmǎo |

| 6 Feb | Ox Guǐchǒu |

Monkey Rénshēn |

Rabbit Xīnmǎo |

Dog Gēngxū |

Snake Jǐsì |

Rat Wùzǐ + |

Goat Dīngwèi |

Tiger Bǐngyín |

Rooster Yǐyǒu − |

Dragon Jiǎchén |

| 26 Jan | Tiger Jiǎyín |

Rooster Guǐyǒu |

Dragon Rénchén + |

Pig Xīnhaì + |

Horse Gēngwǔ + |

Ox Jǐchǒu |

Monkey Wùshēn |

Rabbit Dīngmǎo |

Dog Bǐngxū |

Snake Yǐsì |

| 14 Feb | Rabbit Yǐmǎo |

Dog Jiǎxū |

Snake Guǐsì |

Rat Rénzǐ + |

Goat Xīnwèi + |

Tiger Gēngyín |

Rooster Jǐyǒu − |

Dragon 'Wùchén |

Pig Dīnghaì |

Horse Bǐngwǔ |

| 3 Feb | Dragon Bǐngchén |

Pig Yǐhaì + |

Horse Jiǎwǔ |

Ox Guǐchǒu |

Monkey Rénshēn + |

Rabbit Xīnmǎo |

Dog Gēngxū |

Snake Jǐsì − |

Rat Wùzǐ |

Goat Dīngwèi |

| 23 Jan | Snake Dīngsì |

Rat Bǐngzǐ + |

Goat Yǐwèi + |

Tiger Jiǎyín |

Rooster Guǐyǒu |

Dragon Rénchén |

Pig Xīnhaì |

Horse Gēngwǔ |

Ox Jǐchǒu |

Monkey Wùshēn + |

| 11 Feb | Horse Wùwǔ |

Ox Dīngchǒu |

Monkey Bǐngshēn + |

Rabbit Yǐmǎo |

Dog Jiǎxū − |

Snake Guǐsì − |

Rat Rénzǐ |

Goat Xīnwèi |

Tiger Gēngyín |

Rooster Jǐyǒu − |

| 31 Jan | Goat Jǐwèi + |

Tiger Wùyín |

Rooster Dīngyǒu |

Dragon Bǐngchén |

Pig Yǐhaì |

Horse Jiǎwǔ |

Ox Guǐchǒu |

Monkey Rénshēn + |

Rabbit Xīnmǎo |

Dog Gēngxū − |

| 19 Feb | Monkey Gēngshēn + |

Rabbit Jǐmǎo |

Dog Wùxū − |

Snake Dīngsì − |

Rat Bǐngzǐ |

Goat Yǐwèi |

Tiger Jiǎyín |

Rooster Guǐyǒu |

Dragon Rénchén |

Pig Xīnhaì − |

| 8 Feb | Rooster Xīnyǒu |

Dragon Gēngchén |

Pig Jǐhaì |

Horse Wùwǔ − |

Ox Dīngchǒu − |

Monkey Bǐngshēn |

Rabbit Yǐmǎo |

Dog Jiǎxū |

Snake Guǐsì − |

Rat Rénzǐ − |

| 28 Jan | Dog Rénxū |

Snake Xīnsì − |

Rat Gēngzǐ |

Goat Jǐwèi |

Tiger Wùyín |

Rooster Dīngyǒu |

Dragon Bǐngchén |

Pig Yǐhaì |

Horse Jiǎwǔ − |

Ox Guǐchǒu − |

| 15 Feb | Pig Guǐhaì + |

Horse Rénwǔ |

Ox Xīnchǒu |

Monkey Gēngshēn + |

Rabbit Jǐmǎo + |

Dog Wùxū + |

Snake Dīngsì |

Rat 'Bǐngzǐ |

Goat Yǐwèi |

Tiger Jiǎyín |

| 5 Feb | Rat Jiǎzǐ |

Goat Guǐwèi |

Tiger Rényín |

Rooster Xīnyǒu |

Dragon Gēngchén |

Pig Jǐhaì |

Horse Wùwǔ − |

Ox Dīngchǒu − |

Monkey Bǐngshēn |

Rabbit Yǐmǎo |

| 24 Jan | Ox Yǐchǒu |

Monkey Jiǎshēn + |

Rabbit Guǐmǎo + |

Dog Rénxū + |

Snake Xīnsì |

Rat Gēngzǐ + |

Goat Jǐwèi |

Tiger Wùyín |

Rooster Dīngyǒu |

Dragon Bǐngchén + |

| 12 Feb | Tiger Bǐngyín + |

Rooster Yǐyǒu + |

Dragon Jiǎchén + |

Pig Guǐhaì + |

Horse Rénwǔ |

Ox Xīnchǒu |

Monkey Gēngshēn |

Rabbit Jǐmǎo |

Dog Wùxū |

Snake Dīngsì |

| 2 Feb | Rabbit Dīngmǎo |

Dog Bǐngxū |

Snake Yǐsì |

Rat Jiǎzǐ |

Goat Guǐwèi − |

Tiger Rényín − |

Rooster Xīnyǒu − |

Dragon Gēngchén |

Pig Jǐhaì |

Horse Wùwǔ − |

| 22 Jan | Dragon Wùchén + |

Pig Dīnghaì |

Horse Bǐngwǔ − |

Ox Yǐchǒu |

Monkey Jiǎshēn |

Rabbit Guǐmǎo |

Dog Rénxū |

Snake Xīnsì − |

Rat Gēngzǐ |

Goat Jǐwèi − |

| 9 Feb | Snake Jǐsì + |

Rat Wùzǐ + |

Goat Dīngwèi |

Tiger Bǐngyín |

Rooster Yǐyǒu |

Dragon Jiǎchén + |

Pig Guǐhaì + |

Horse Rénwǔ |

Ox Xīnchǒu |

Monkey Gēngshēn |

| 29 Jan | Horse Gēngwǔ + |

Ox Jǐchǒu |

Monkey Wùshēn + |

Rabbit Dīngmǎo |

Dog Bǐngxū |

Snake Yǐsì |

Rat Jiǎzǐ + |

Goat Guǐwèi |

Tiger Rényín |

Rooster Xīnyǒu − |

| Note: a day later; Note: a day earlier. Note: The New Year's Day of 1985 is 20 Feb, a month later. Note: AM=anno Mínguó | ||||||||||

Mythology

According to tales and legends, the beginning of the Chinese New Year started with a mythical beast called the Nian. Nian would eat villagers, especially children. One year, all the villagers decided to go hide from the beast. An old man appeared before the villagers went into hiding and said that he's going to stay the night, and decided to get revenge on the Nian. All the villagers thought he was insane. The old man put red papers up and set off firecrackers. The day after, the villagers came back to their town to see that nothing was destroyed. They assumed that the old man was a deity who came to save them. The villagers then understood that the Nian was afraid of the color red and loud noises. When the New Year was about to come, the villagers would wear red clothes, hang red lanterns, and red spring scrolls on windows and doors. People also used firecrackers to frighten away the Nian. From then on, Nian never came to the village again. The Nian was eventually captured by Hongjun Laozu, an ancient Taoist monk. After that, Nian retreated to a nearby mountain. The name of the mountain has long been lost over the years.

Public holiday

Chinese New Year is observed as a public holiday in some countries and territories where there is a sizable Chinese and Korean population. Since Chinese New Year falls on different dates on the Gregorian calendar every year on different days of the week, some of these governments opt to shift working days in order to accommodate a longer public holiday. In some countries, a statutory holiday is added on the following work day when the New Year falls on a weekend, as in the case of 2013, where the New Year's Eve (9 February) falls on Saturday and the New Year's Day (10 February) on Sunday. Depending on the country, the holiday may be termed differently; common names are "Chinese New Year", "Lunar New Year", "New Year Festival", and "Spring Festival".

For New Year celebrations that are lunar but are outside of China and Chinese diaspora (such as Korea's Seollal and Vietnam's Tết), see the article on Lunar New Year.

For other countries where Chinese New Year is celebrated but not an official holiday, see the table below.

| Country and region | Official name | Description | Number of days |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brunei | Tahun Baru Cina | New Year's Eve (half-day) and New Year's Day. | 1 |

| Hong Kong | Lunar New Year | The first three days. | 3 |

| Indonesia | Tahun Baru Imlek (Sin Cia) | New Year's Day. | 1 |

| Macau | Lunar New Year | The first three days. | 3 |

| Mainland China | Spring Festival (Chūn Jié) | The first 3 days. Usually, the Saturday before and the Sunday after Chinese New Year are declared working days, and the 2 additionally gained holidays are added to the official 3 days of holiday, so that people have 7 consecutive days, including weekends. | 7 (de jure) 3 (de facto) |

| Malaysia | Tahun Baru Cina | The first 2 days and a half-day on New Year's Eve. | 2 |

| Philippines | Bagong Taon ng mga Tsino/Intsik (Tagalog) / Año Nuevo de Chino (Spanish) | New Year's Eve (half-day) and New Year's Day. | 1 |

| Taiwan | Spring Festival | New Year's Eve and the first 3 working days. | 4 |

| Thailand | Wan Trut Chin (Chinese New Year's Day) | Divided into 3 days, the first day is the Wan chai (Template:Lang-th; pay day), meaning the day that people go out to shop for offerings, second day is the Wan wai (วันไหว้; worship day), is a day of worshiping the gods and ancestral spirits, which is divided into three periods: dawn, late morning and afternoon, the third day is a Wan tieow (วันเที่ยว; holiday), is a holiday that everyone will leave the house to travel or to bless relatives or respectable people. And often wear red clothes because it is believed to bring auspiciousness to life. | 3 |

| Singapore | Chinese New Year | The first 2 days and a half-day on New Year's Eve. | 2 |

| Vietnam | Tết Nguyên Đán | The first 3 days. | 3 |

| Suriname | Lunar New Year | New Year's Day. | 1 |

Festivities

Red couplets and red lanterns are displayed on the door frames and light up the atmosphere. The air is filled with strong Chinese emotions. In stores in Beijing, Shanghai, Wuhan, and other cities, products of traditional Chinese style have started to lead fashion trend. Buy yourself a Chinese-style coat, get your kids tiger-head hats and shoes, and decorate your home with some beautiful red Chinese knots, then you will have an authentic Chinese-style Spring Festival.

— Xinwen Lianbo, January 2001, quoted by Li Ren, Imagining China in the Era of Global Consumerism and Local Consciousness

During the festival, people around China will prepare different gourmet for families and guests. Influenced by the flourished cultures, foods from different places look and taste totally different. Among them, the most well-known ones are dumplings from northern China and Tangyuan from southern China.

Preceding days

On the eighth day of the lunar month prior to Chinese New Year, the Laba holiday (simplified Chinese: 腊八; traditional Chinese: 臘八; pinyin: làbā), a traditional porridge, Laba porridge (simplified Chinese: 腊八粥; traditional Chinese: 臘八粥; pinyin: làbā zhōu), is served in remembrance of an ancient festival, called La, that occurred shortly after the winter solstice. Pickles such as Laba garlic, which turns green from vinegar, are also made on this day. For those that practice Buddhism, the Laba holiday is also considered Bodhi Day. Layue (simplified Chinese: 腊月; traditional Chinese: 臘月; pinyin: Làyuè) is a term often associated with Chinese New Year as it refers to the sacrifices held in honor of the gods in the twelfth lunar month, hence the cured meats of Chinese New Year are known as larou (simplified Chinese: 腊肉; traditional Chinese: 臘肉; pinyin: làròu). The porridge was prepared by the women of the household at first light, with the first bowl offered to the family's ancestors and the household deities. Every member of the family was then served a bowl, with leftovers distributed to relatives and friends. It's still served as a special breakfast on this day in some Chinese homes. The concept of the "La month" is similar to Advent in Christianity. Many families eat vegetarian on Chinese New Year eve, the garlic and preserved meat are eaten on Chinese New Year day.

On the days immediately before the New Year celebration, Chinese families give their homes a thorough cleaning. There is a Cantonese saying "Wash away the dirt on nin ya baat" (Chinese: 年廿八,洗邋遢; pinyin: nián niàn bā, xǐ lātà; Jyutping: nin4 jaa6 baat3, sai2 laap6 taap3 (laat6 taat3)), but the practice is not restricted to nin ya baat (the 28th day of month 12). It is believed the cleaning sweeps away the bad luck of the preceding year and makes their homes ready for good luck. Brooms and dust pans are put away on the first day so that the newly arrived good luck cannot be swept away. Some people give their homes, doors and window-frames a new coat of red paint; decorators and paper-hangers do a year-end rush of business prior to Chinese New Year. Homes are often decorated with paper cutouts of Chinese auspicious phrases and couplets. Purchasing new clothing and shoes also symbolize a new start. Any hair cuts need to be completed before the New Year, as cutting hair on New Year is considered bad luck due to the homonymic nature of the word "hair" (fa) and the word for "prosperity". Businesses are expected to pay off all the debts outstanding for the year before the new year eve, extending to debts of gratitude. Thus it is a common practice to send gifts and rice to close business associates, and extended family members.

In many households where Buddhism or Taoism is prevalent, home altars and statues are cleaned thoroughly, and decorations used to adorn altars over the past year are taken down and burned a week before the new year starts, to be replaced with new decorations. Taoists (and Buddhists to a lesser extent) will also "send gods back to heaven" (Chinese: 送神; pinyin: sòngshén), an example would be burning a paper effigy of Zao Jun the Kitchen God, the recorder of family functions. This is done so that the Kitchen God can report to the Jade Emperor of the family household's transgressions and good deeds. Families often offer sweet foods (such as candy) in order to "bribe" the deities into reporting good things about the family.

Prior to the Reunion Dinner, a prayer of thanksgiving is held to mark the safe passage of the previous year. Confucianists take the opportunity to remember their ancestors, and those who had lived before them are revered. Some people do not give a Buddhist prayer due to the influence of Christianity, with a Christian prayer offered instead.

New Year's Eve

The biggest event of any Chinese New Year's Eve is the annual reunion dinner. Dishes consisting of special meats are served at the tables, as a main course for the dinner and offering for the New Year. This meal is comparable to Thanksgiving dinner in the U.S. and remotely similar to Christmas dinner in other countries with a high percentage of Christians.

In northern China, it is customary to make dumplings (jiaozi) after dinner to eat around midnight. Dumplings symbolize wealth because their shape resembles a Chinese sycee. In contrast, in the South, it is customary to make a glutinous new year cake (niangao) and send pieces of it as gifts to relatives and friends in the coming days. Niángāo literally means "new year cake" with a homophonous meaning of "increasingly prosperous year in year out".

After dinner, some families go to local temples hours before the new year begins to pray for a prosperous new year by lighting the first incense of the year; however in modern practice, many households hold parties and even hold a countdown to the new year. Traditionally, firecrackers were lit to scare away evil spirits with the household doors sealed, not to be reopened until the new morning in a ritual called "opening the door of fortune" (simplified Chinese: 开财门; traditional Chinese: 開財門; pinyin: kāicáimén).

Beginning in 1982, the CCTV New Year's Gala is broadcast in China four hours before the start of the New Year and lasts until the succeeding early morning. Watching it has gradually become a tradition in northern China. A tradition of going to bed late on New Year's Eve, or even keeping awake the whole night and morning, known as shousui (守岁), is still practised as it is thought to add on to one's parents' longevity.

First day

The first day is for the welcoming of the deities of the heavens and earth, officially beginning at midnight. It is a traditional practice to light fireworks, burn bamboo sticks and firecrackers and to make as much of a din as possible to chase off the evil spirits as encapsulated by nian of which the term Guo Nian was derived. Many Buddhists abstain from meat consumption on the first day because it is believed to ensure longevity for them. Some consider lighting fires and using knives to be bad luck on New Year's Day, so all food to be consumed is cooked the days before. On this day, it is considered bad luck to use the broom, as good fortune is not to be "swept away" symbolically.

Most importantly, the first day of Chinese New Year is a time to honor one's elders and families visit the oldest and most senior members of their extended families, usually their parents, grandparents and great-grandparents.

For Buddhists, the first day is also the birthday of Maitreya Bodhisattva (better known as the more familiar Budai Luohan), the Buddha-to-be. People also abstain from killing animals.

Some families may invite a lion dance troupe as a symbolic ritual to usher in the Chinese New Year as well as to evict bad spirits from the premises. Members of the family who are married also give red envelopes containing cash known as lai see (Cantonese dialect) or angpow (Hokkien dialect/Fujian), or hongbao (Mandarin), a form of blessings and to suppress the aging and challenges associated with the coming year, to junior members of the family, mostly children and teenagers. Business managers also give bonuses through red packets to employees for good luck, smooth-sailing, good health and wealth.

While fireworks and firecrackers are traditionally very popular, some regions have banned them due to concerns over fire hazards. For this reason, various city governments (e.g., Kowloon, Beijing, Shanghai for a number of years) issued bans over fireworks and firecrackers in certain precincts of the city. As a substitute, large-scale fireworks display have been launched by governments in such city-states as Hong Kong and Singapore. However, it is a tradition that the indigenous peoples of the walled villages of New Territories, Hong Kong are permitted to light firecrackers and launch fireworks in a limited scale.

Second day

The second day of the Chinese New Year, known as "beginning of the year" (simplified Chinese: 开年; traditional Chinese: 開年; pinyin: kāinián), was when married daughters visited their birth parents, relatives and close friends. (Traditionally, married daughters didn't have the opportunity to visit their birth families frequently.)

During the days of imperial China, "beggars and other unemployed people circulate from family to family, carrying a picture shouting, "Cai Shen dao!" ." Householders would respond with "lucky money" to reward the messengers. Business people of the Cantonese dialect group will hold a 'Hoi Nin' prayer to start their business on the 2nd day of Chinese New Year so they will be blessed with good luck and prosperity in their business for the year.

As this day is believed to be The Birthday of Che Kung, a deity worshipped in Hong Kong, worshippers go to Che Kung Temples to pray for his blessing. A representative from the government asks Che Kung about the city's fortune through kau cim.

Third day

The third day is known as "red mouth" (Chinese: 赤口; pinyin: Chìkǒu). Chikou is also called "Chigou's Day" (Chinese: 赤狗日; pinyin: Chìgǒurì). Chigou, literally "red dog", is an epithet of "the God of Blazing Wrath" (Chinese: 熛怒之神; pinyin: Biāo nù zhī shén). Rural villagers continue the tradition of burning paper offerings over trash fires. It is considered an unlucky day to have guests or go visiting. Hakka villagers in rural Hong Kong in the 1960s called it the Day of the Poor Devil and believed everyone should stay at home. This is also considered a propitious day to visit the temple of the God of Wealth and have one's future told.

Fourth day

In those communities that celebrate Chinese New Year for 15 days, the fourth day is when corporate "spring dinners" kick off and business returns to normal. Other areas that have a longer Chinese New Year holiday will celebrate and welcome the gods that were previously sent on this day.

Fifth day

This day is the god of Wealth's birthday. In northern China, people eat jiaozi, or dumplings, on the morning of powu (Chinese: 破五; pinyin: pòwǔ). In Taiwan, businesses traditionally re-open on the next day (the sixth day), accompanied by firecrackers.

It is also common in China that on the 5th day people will shoot off firecrackers to get Guan Yu's attention, thus ensuring his favor and good fortune for the new year.

Sixth day

The sixth day is Horse's Day, on which people drive away the Ghost of Poverty by throwing out the garbage stored up during the festival. The ways vary but basically have the same meaning - to drive away the Ghost of Poverty, which reflects the general desire of the Chinese people to ring out the old and ring in the new, to send away the previous poverty and hardship and to usher in the good life of the New Year.

Seventh day

Main article: RenriThe seventh day, traditionally known as Renri (the common person's birthday), is the day when everyone grows one year older. In some overseas Chinese communities in Southeast Asia, such as Malaysia and Singapore, it is also the day when tossed raw fish salad, yusheng, is eaten for continued wealth and prosperity.

For many Chinese Buddhists, this is another day to avoid meat, the seventh day commemorating the birth of Sakra, lord of the devas in Buddhist cosmology who is analogous to the Jade Emperor.

Eighth day

Another family dinner is held to celebrate the eve of the birth of the Jade Emperor, the ruler of heaven. People normally return to work by the eighth day, therefore the Store owners will host a lunch/dinner with their employees, thanking their employees for the work they have done for the whole year.

Ninth day

The ninth day of the New Year is a day for Chinese to offer prayers to the Jade Emperor of Heaven in the Daoist Pantheon. The ninth day is traditionally the birthday of the Jade Emperor. This day, called Ti Kong Dan (Hokkien: 天公誕 Thiⁿ-kong Tan), Ti Kong Si (Hokkien: 天公生 Thiⁿ-kong Siⁿ) or Pai Ti Kong (Hokkien: 拜天公 Pài Thiⁿ-kong), is especially important to Hokkiens, even more important than the first day of the Chinese New Year.

Come midnight of the eighth day of the new year, Hokkiens will offer thanks to the Emperor of Heaven. A prominent requisite offering is sugarcane. Legend holds that the Hokkien were spared from a massacre by Japanese pirates by hiding in a sugarcane plantation during the eighth and ninth days of the Chinese New Year, coinciding with the Jade Emperor's birthday. Since "sugarcane" (Hokkien: 甘蔗 kam-chià) is a near homonym to "thank you" (Hokkien: 感謝 kám-siā) in the Hokkien dialect, Hokkiens offer sugarcane on the eve of his birthday, symbolic of their gratitude.

In the morning of this birthday (traditionally anytime from midnight to 7 am), Taiwanese households set up an altar table with 3 layers: one top (containing offertories of six vegetables (Chinese: 六齋; pinyin: liù zhāi), noodles, fruits, cakes, tangyuan, vegetable bowls, and unripe betel, all decorated with paper lanterns) and two lower levels (containing the five sacrifices and wines) to honor the deities below the Jade Emperor. The household then kneels three times and kowtows nine times to pay obeisance and wish him a long life.

Incense, tea, fruit, vegetarian food or roast pig, and gold paper is served as a customary protocol for paying respect to an honored person.

Tenth day

The Jade Emperor's birthday party is celebrated on this day.

Fifteenth day

The fifteenth day of the new year is celebrated as "Yuanxiao Festival" (simplified Chinese: 元宵节; traditional Chinese: 元宵節; pinyin: Yuán xiāo jié), also known as "Shangyuan Festival" (simplified Chinese: 上元节; traditional Chinese: 上元節; pinyin: Shàng yuán jié) or the Lantern Festival (otherwise known as Chap Goh Mei Chinese: 十五暝; pinyin: Shíwǔmíng; lit. 'the fifteen night' in Fujian dialect). Rice dumplings tangyuan (simplified Chinese: 汤圆; traditional Chinese: 湯圓; pinyin: tang yuán), a sweet glutinous rice ball brewed in a soup, are eaten this day. Candles are lit outside houses as a way to guide wayward spirits home. This day is celebrated as the Lantern Festival, and families walk the street carrying lighted lantern.

In China, Malaysia, and Singapore, this day is celebrated by individuals seeking a romantic partner, akin to Valentine's Day. Nowadays, single women write their contact number on mandarin oranges and throw them in a river or a lake after which single men collect the oranges and eat them. The taste is an indication of their possible love: sweet represents a good fate while sour represents a bad fate.

This day often marks the end of the Chinese New Year festivities.

Traditional food

A reunion dinner (nián yè fàn) is held on New Year's Eve during which family members gather for a celebration. The venue will usually be in or near the home of the most senior member of the family. The New Year's Eve dinner is very large and sumptuous and traditionally includes dishes of meat (namely, pork and chicken) and fish. Most reunion dinners also feature a communal hot pot as it is believed to signify the coming together of the family members for the meal. Most reunion dinners (particularly in the Southern regions) also prominently feature specialty meats (e.g. wax-cured meats like duck and Chinese sausage) and seafood (e.g. lobster and abalone) that are usually reserved for this and other special occasions during the remainder of the year. In most areas, fish (traditional Chinese: 魚; simplified Chinese: 鱼; pinyin: yú) is included, but not eaten completely (and the remainder is stored overnight), as the Chinese phrase "may there be surpluses every year" (traditional Chinese: 年年有餘; simplified Chinese: 年年有余; pinyin: niánnián yǒu yú) sounds the same as "let there be fish every year." Eight individual dishes are served to reflect the belief of good fortune associated with the number. If in the previous year a death was experienced in the family, seven dishes are served.

Red packets for the immediate family are sometimes distributed during the reunion dinner. These packets contain money in an amount that reflects good luck and honorability. Several foods are consumed to usher in wealth, happiness, and good fortune. Several of the Chinese food names are homophones for words that also mean good things.

Like many other New Year dishes, certain ingredients also take special precedence over others as these ingredients also have similar-sounding names with prosperity, good luck, or even counting money.

| Food item | Description |

|---|---|

| Buddha's delight | An elaborate vegetarian dish served by Chinese families on the eve and the first day of the New Year. A type of black hair-like algae, pronounced "fat choy" in Cantonese, is also featured in the dish for its name, which sounds like "prosperity". Hakkas usually serve kiu nyuk (Chinese: 扣肉; pinyin: kòuròu) and ngiong teu fu. |

| Chicken | Boiled chicken is served because it is figured that any family, no matter how humble their circumstances, can afford a chicken for Chinese New Year. |

| Apples | Apples symbolize peace because the word for apple ("ping") is a homonym of the word for peace. |

| Fish | Is usually eaten or merely displayed on the eve of Chinese New Year. The pronunciation of fish (魚yú) makes it a homophone for "surpluses"(餘yú). |

| Leek | Is usually served in a dish with rondelles of Chinese sausage or Chinese cured meat during Chinese New Year. The pronunciation of leek (蒜苗/大蒜Suàn miáo/Dà suàn) makes it a homophone for "calculating (money)" (算Suàn). The Chinese cured meat is so chosen because it is traditionally the primary method for storing meat over the winter and the meat rondelles resemble coins. |

| Jau gok | The main Chinese new year dumpling for Cantonese families. It is believed to resemble a sycee or yuánbǎo, the old Chinese gold and silver ingots, and to represent prosperity for the coming year. |

| Jiaozi | The common dumpling eaten in northern China, also believed to resemble sycee. |

| Mandarin oranges | Oranges, particularly mandarin oranges, are a common fruit during Chinese New Year. They are particularly associated with the festival in southern China, where its name is a homophone of the word for "luck" in dialects such as Teochew (in which 橘, jú, and 吉, jí, are both pronounced gik). |

| Melon seed/Guazi (Chinese: 瓜子; pinyin: guāzi) |

Other variations include sunflower, pumpkin and other seeds. It symbolizes fertility and having many children. |

| Niangao | Most popular in eastern China (Jiangsu, Zhejiang and Shanghai) because its pronunciation is a homophone for "a more prosperous year (年高 lit. year high)". Niangao is also popular in the Philippines because of its large Chinese population and is known as tikoy (Chinese: 甜粿, from Min Nan) there. Known as Chinese New Year pudding, niangao is made up of glutinous rice flour, wheat starch, salt, water, and sugar. The color of the sugar used determines the color of the pudding (white or brown). |

| Noodles | Families may serve uncut noodles (making them as long as they can), which represent longevity and long life, though this practice is not limited to the new year. |

| Sweets | Sweets and similar dried fruit goods are stored in a red or black Chinese candy box. |

| Rougan (Yok Gon) | Chinese salty-sweet dried meat, akin to jerky, which is trimmed of the fat, sliced, marinated and then smoked for later consumption or as a gift. |

| Taro cakes (Chinese: 芋頭糕, yùtougāo) | Made from the vegetable taro, the cakes are cut into squares and often fried. |

| Turnip cakes (Chinese: 蘿蔔糕, luóbogāo) | A dish made of shredded radish and rice flour, usually fried and cut into small squares. |

| Yusheng or Yee sang (traditional Chinese: 魚生; simplified Chinese: 鱼生; pinyin: yúshēng) | Raw fish salad. Eating this salad is said to bring good luck. This dish is usually eaten on the seventh day of the New Year, but may also be eaten throughout the period. |

Practices

History

In 1928, the ruling Kuomintang party in China decreed that Chinese New Year will fall on 1 Jan of the Gregorian Calendar, but this was abandoned due to overwhelming opposition from the populace. In 1967 during the Cultural Revolution, official Chinese New Year celebrations were banned in China. The State Council of the People's Republic of China announced that the public should "Change Customs", have a "revolutionized and fighting Spring Festival", and since people needed to work on Chinese New Year Eve, they did not have holidays during Spring Festival day. The public celebrations were reinstated by the time of the Chinese economic reform.

Red envelopes

Traditionally, red envelopes or red packets (Cantonese: lai sze or lai see; 利是, 利市 or 利事; Pinyin: lìshì; Mandarin (simplified) hóngbāo 红包; Hokkien: ang pow; POJ: âng-pau; Hakka: fung bao) are passed out during the Chinese New Year's celebrations, from married couples or the elderly to unmarried juniors or children.

During this period, red packets are also known as 壓歲錢/压岁钱 (yàsuìqián, which was evolved from 壓祟錢/压祟钱, literally, "the money used to suppress or put down the evil spirit"). Red packets almost always contain money, usually varying from a couple of dollars to several hundred. Per custom, the amount of money in the red packets should be of even numbers, as odd numbers are associated with cash given during funerals (帛金: báijīn). The number 8 is considered lucky (for its homophone for "wealth"), and $8 is commonly found in the red envelopes in the US. The number six (六, liù) is also very lucky as it sounds like "smooth" (流, liú), in the sense of having a smooth year. The number four (四) is the worst because its homophone is "death" (死). Sometimes chocolate coins are found in the red packet.

Odd and even numbers are determined by the first digit, rather than the last. Thirty and fifty, for example, are odd numbers and are thus appropriate as funeral cash gifts. However, it is common and quite acceptable to have cash gifts in a red packet using a single bank note – with ten or fifty yuan bills used frequently. It is customary for the bills to be brand new printed money. Everything regarding the New Year has to be new in order to have good luck and fortune.

The act of asking for red packets is normally called (Mandarin): 讨紅包 tǎo-hóngbāo, 要利是 or (Cantonese): 逗利是. A married person would not turn down such a request as it would mean that he or she would be "out of luck" in the new year. Red packets are generally given by established married couples to the younger non-married children of the family. It is custom and polite for children to wish elders a happy new year and a year of happiness, health and good fortune before accepting the red envelope. Red envelopes are then kept under the pillow and slept on for seven nights after Chinese New Year before opening because that symbolizes good luck and fortune.

In Taiwan in the 2000s, some employers also gave red packets as a bonus to maids, nurses or domestic workers from Southeast Asian countries, although whether this is appropriate is controversial.

The Japanese have a similar tradition of giving money during the New Year, called Otoshidama.

Gift exchange

In addition to red envelopes, which are usually given from older people to younger people, small gifts (usually food or sweets) are also exchanged between friends or relatives (of different households) during Chinese New Year. Gifts are usually brought when visiting friends or relatives at their homes. Common gifts include fruits (typically oranges, but never trade pears), cakes, biscuits, chocolates, and candies.

Certain items should not be given, as they are considered taboo. Taboo gifts include:

- items associated with funerals (i.e. handkerchiefs, towels, chrysanthemums, items colored white and black)

- items that show that time is running out (i.e. clocks and watches)

- sharp objects that symbolize cutting a tie (i.e. scissors and knives)

- items that symbolize that you want to walk away from a relationship (examples: shoes and sandals)

- mirrors

- homonyms for unpleasant topics (examples: "clock" sounds like "the funeral ritual", green hats because "wear a green hat" sounds like "cuckold", "handkerchief" sounds like "goodbye", "pear" sounds like "separate", and "umbrella" sounds like "disperse").

Markets

Markets or village fairs are set up as the New Year is approaching. These usually open-air markets feature new year related products such as flowers, toys, clothing, and even fireworks and firecrackers. It is convenient for people to buy gifts for their new year visits as well as their home decorations. In some places, the practice of shopping for the perfect plum tree is not dissimilar to the Western tradition of buying a Christmas tree.

Hong Kong filmmakers also release "New Year celebration films" (賀歲片), mostly comedies, at this time of year.

Fireworks

Bamboo stems filled with gunpowder that was burnt to create small explosions were once used in ancient China to drive away evil spirits. In modern times, this method has eventually evolved into the use of firecrackers during the festive season. Firecrackers are usually strung on a long fused string so it can be hung down. Each firecracker is rolled up in red papers, as red is auspicious, with gunpowder in its core. Once ignited, the firecracker lets out a loud popping noise and, as they are usually strung together by the hundreds, the firecrackers are known for their deafening explosions that are thought to scare away evil spirits. The burning of firecrackers also signifies a joyful time of year and has become an integral aspect of Chinese New Year celebrations.

Firecracker bans

Although the use of firecrackers are considered a traditional part of Chinese New Year festivities safety issue are present. In response to these issues, many governments and authorities eventually enacted laws completely banning the use of firecrackers.

- Taiwan – A ban was enforced in 2008, prohibiting the use firecrackers in urban areas. Firecrackers were still allowed for use in rural areas.

- Mainland China – Firecrackers were banned in a large amount of cities and urban areas in the 1990s. However, many cities have relaxed their restrictions since that time; for example, Beijing's urban districts revoked their ban in 2005, although they are still typically not allowed inside the 5th Ring Road. Even so, this is overlooked by authorities for the festival, provided there are no government buildings nearby. Bans are rare in rural areas.

- Vietnam – A nationwide ban on firecrackers was implemented in 1996.

- Hong Kong – Fireworks are banned in Hong Kong for security reasons. The Hong Kong government runs an annual fireworks display in Victoria Harbour on the second day of the Chinese New Year for the public.

- Singapore – a partial ban on firecrackers was imposed in March 1970 after a fire resulted in 6 fatalities and 68 injuries. This was extended to a total ban in August 1972; this total ban was triggered by an explosion that killed two people and an attack on two police officers attempting to stop a group from letting off firecrackers in February 1972. As a result of this ban, the Chingay Parade was set up to preserve the spirit and culture. However, in 2003, the government allowed firecrackers to be set off during the festive season. At the Chinese New Year light-up in Chinatown, at the stroke of midnight on the first day of the Chinese New Year, firecrackers are set off under controlled conditions by the Singapore Tourism Board with assistance from demolition experts from the Singapore Armed Forces. Other occasions where firecrackers are allowed to be set off are determined by the tourism board or other government organizations. However, they are not allowed to be commercially sold.

- Malaysia – Firecrackers are banned for similar reasons as in Singapore.

- Indonesia – Firecrackers and fireworks are forbidden in public during the Chinese New Year, especially in areas with a significant non-Chinese population in order to avoid any conflict between the two. However, there were some exceptions. The usage of firecrackers is legal in some metropolitan areas such as Jakarta and Medan, where the degree of racial and cultural tolerance is higher.

- United States – In 2007, New York City lifted its decades-old ban on firecrackers, allowing a display of 300,000 firecrackers to be set off in Chinatown's Chatham Square. Under the supervision of the fire and police departments, Chinatown, Los Angeles regularly lights firecrackers every New Year's Eve, mostly at temples and the shrines of benevolent associations. The San Francisco Chinese New Year Parade, the largest outside China, is accompanied by numerous firecrackers, both officially sanctioned and illicit.

- Australia – Australia, except the Northern Territory, does not allow use of fireworks at all, except when used by a licensed pyrotechnician. These rules also need a permit from local government, and from any relevant local bodies such as maritime or aviation authorities (as relevant to the types of fireworks being used) and hospitals, schools, etc., within a certain range.

- Philippines – Despite the rise in firecracker-related injuries in 2009, the Department of Health has acknowledged that a total ban on firecrackers in the country will be hard to implement. Davao City, the first city in the country to impose a firecracker ban, has enjoyed injury-free celebrations for at least the last 15 years. Their ban has been in effect since 2002.

Music

"Happy New Year!" (Chinese: 新年好呀; pinyin: Xīn Nián Hǎo Ya; lit. 'New Year's Good', 'Ya') is a popular children's song for the New Year holiday. The melody is similar to the American folk song, Oh My Darling, Clementine.

- Chorus:

- Happy New Year! Happy New Year! (Chinese: 新年好呀!新年好呀!; pinyin: Xīnnián hǎo ya! Xīnnián hǎo ya!)

- Happy New Year to you all! (Chinese: 祝贺大家新年好!; pinyin: Zhùhè dàjiā xīnnián hǎo!)

- We are singing; we are dancing. (Chinese: 我们唱歌,我们跳舞。; pinyin: Wǒmen chànggē, wǒmen tiàowǔ.)

- Happy New Year to you all! (Chinese: 祝贺大家新年好!; pinyin: Zhùhè dàjiā xīnnián hǎo!)

Movie

Main article: Lunar New Year FilmLunar New Year Film is also a Chinese cultural identity, during the New Year holidays, the stage boss gathers the most popular actors whom from various troupes let them perform repertories from Qing dynasty. Nowadays people prefer celebrating new year with their family by watching movie together.

Clothing

The color red is commonly worn throughout Chinese New Year; traditional beliefs held that red could scare away evil spirits and bad fortune. The wearing of new clothes is another clothing custom during the festival, the new clothes symbolize a new beginning in the year, and enough things to use and wear in the this time.

Family portrait

In some places, the taking of a family portrait is an important ceremony after the relatives are gathered. The photo is taken at the hall of the house or taken in front of the house. The most senior male head of the family sits in the center.

Symbolism

See also: Fu character

As with all cultures, Chinese New Year traditions incorporate elements that are symbolic of deeper meaning. One common example of Chinese New Year symbolism is the red diamond-shaped fu characters (Chinese: 福; pinyin: fú; Cantonese Yale: fuk1; lit. 'blessings', 'happiness'), which are displayed on the entrances of Chinese homes. This sign is usually seen hanging upside down, since the Chinese word dao (Chinese: 倒; pinyin: dào; lit. 'upside down'), is homophonous or nearly homophonous with (Chinese: 到; pinyin: dào; lit. 'arrive') in all varieties of Chinese. Therefore, it symbolizes the arrival of luck, happiness, and prosperity.

For the Cantonese-speaking people, if the fu sign is hung upside down, the implied dao (upside down) sounds like the Cantonese word for "pour", producing "pour the luck ", which would usually symbolize bad luck; this is why the fu character is not usually hung upside-down in Cantonese communities.

Red is the predominant color used in New Year celebrations. Red is the emblem of joy, and this color also symbolizes virtue, truth and sincerity. On the Chinese opera stage, a painted red face usually denotes a sacred or loyal personage and sometimes a great emperor. Candies, cakes, decorations and many things associated with the New Year and its ceremonies are colored red. The sound of the Chinese word for "red" (simplified Chinese: 红; traditional Chinese: 紅; pinyin: hóng; Cantonese Yale: hung4) is in Mandarin homophonous with the word for "prosperous." Therefore, red is an auspicious color and has an auspicious sound.

Nianhua

Nianhua can be a form of Chinese colored woodblock printing, for decoration during Chinese New Year.

Flowers

The following are popular floral decorations for the New Year and are available at new year markets.

Floral Decor Meaning Plum Blossom symbolizes luckiness Kumquat symbolizes prosperity Calamondin Symbolizes luck Narcissus symbolizes prosperity Bamboo a plant used for any time of year Sunflower means to have a good year Eggplant a plant to heal all of your sicknesses Chom Mon Plant a plant which gives you tranquility

Icons and ornaments

Icons Meaning Illustrations Lanterns These lanterns that differ from those of Mid-Autumn Festival in general. They will be red in color and tend to be oval in shape. These are the traditional Chinese paper lanterns. Those lanterns, used on the fifteenth day of the Chinese New Year for the Lantern Festival, are bright, colorful, and in many different sizes and shapes. Decorations Decorations generally convey a New Year greeting. They are not advertisements. Fai Chun—Chinese calligraphy of auspicious Chinese idioms on typically red posters—are hung on doorways and walls. Other decorations include a New year picture, Chinese knots, and papercutting and couplets.

Dragon dance and Lion dance Dragon and lion dances are common during Chinese New Year. It is believed that the loud beats of the drum and the deafening sounds of the cymbals together with the face of the Dragon or lion dancing aggressively can evict bad or evil spirits. Lion dances are also popular for opening of businesses in Hong Kong and Macau.

Fortune gods Cai Shen Ye, Che Kung, etc.

Spring travel

Traditionally, families gather together during the Chinese New Year. In modern China, migrant workers in China travel home to have reunion dinners with their families on Chinese New Year's Eve. Owing to a large number of interprovincial travelers, special arrangements were made by railways, buses and airlines starting from 15 days before the New Year's Day. This 40-day period is called chunyun, and is known as the world's largest annual migration. More interurban trips are taken in mainland China in this period than the total population of China.

In Taiwan, spring travel is also a major event. The majority of transportation in western Taiwan is in a north-south direction: long distance travel between urbanized north and hometowns in the rural south. Transportation in eastern Taiwan and that between Taiwan and its islands is less convenient. Cross-strait flights between Taiwan and mainland China began in 2003 as part of Three Links, mostly for "Taiwanese businessmen" to return to Taiwan for the new year.

Festivities outside Greater China

Chinese New Year is also celebrated annually in many countries with significant Chinese populations. These include countries throughout Asia, Oceania, and North America. Sydney, London, and San Francisco claim to host the largest New Year celebration outside of Asia and South America.

Southeast Asia

In some countries of Southeast Asia, Chinese New Year is a national public holiday and considered to be one of the most important holidays of the year. Chinese New Year's Eve is typically a half-day holiday for Malaysia and Singapore. The biggest celebrations take place in Malaysia (notably in Kuala Lumpur, George Town and Klang) and Singapore.

In Singapore, Chinese New Year is accompanied by various festive activities. One of the main highlights is the Chinatown celebrations. In 2010, this included a Festive Street Bazaar, nightly staged shows at Kreta Ayer Square and a lion dance competition. The Chingay Parade also features prominently in the celebrations. It is an annual street parade in Singapore, well known for its colorful floats and wide variety of cultural performances. The highlights of the Parade for 2011 include a Fire Party, multi-ethnic performances and an unprecedented travelling dance competition.

In the Philippines, Chinese New Year is considered to be the most important festival for Filipino-Chinese, and its celebration has also extended to the non-Chinese majority Filipinos. In 2012, Chinese New Year was included in public holidays in the Philippines, which is only the New Year's Day itself.(Sin-nî: Chinese new years in Philippine Hokkien)

In Thailand, one of the most populous Chinese descent populated countries. Also celebrated the great Chinese New Year festivities throughout the country, especially in provinces where many Chinese descent live such as Nakhon Sawan, Suphan Buri, Phuket etc. Which is considered to promote tourism in the same agenda as well.

In the capital, Bangkok in Chinatown, Yaowarat Road, there is a great celebration. Which usually closes the road making it a pedestrian street and often have a member of royal family came to be the president of the ceremony, always open every year, such as Princess Maha Chakri Sirindhorn.

Indonesia

In Indonesia, the Chinese New Year is officially named as Hari Tahun Baru Imlek, or Sin Cia in Hokkien. It was celebrated as one of the official national religious holiday by Chinese-Indonesians since 18 June 1946 to 1 January 1953 through government regulation signed by President Sukarno on 18 June 1946. It was unofficially celebrated by ethnic Chinese from 1953 to 1967 based on government regulation signed by Vice President Muhammad Hatta in 5 February 1953 which annul the previous regulation, among others, the Chinese New Year as a national religious holiday, Effectively from 6 December 1967, until 1998, the spiritual practice to celebrate the Chinese New Year by Chinese families was restricted specifically only inside of the Chinese house. This restriction is made by Indonesian government through a Presidential Instruction, Instruksi Presiden No.14 Tahun 1967, signed by President Suharto. This restriction is ended when the regime has changed and the President Suharto was overthrown. The celebration is conducted unofficially by Chinese community from 1999 to 2000. On 17 January 2000, the President Abdurrahman Wahid issued a Presidential Decree through Keputusan Presiden RI No 6 Tahun 2000 to annul Instruksi Presiden No.14 Tahun 1967. On 19 January 2001, the Ministry of Religious Affairs (Kementerian Agama Republik Indonesia) issued a Decree through Keputusan Menteri Agama RI No 13 Tahun 2001 tentang Imlek sebagai Hari Libur Nasional to set of Hari Tahun Baru Imlek as a Facultative Holiday for Chinese Community. Through the Presidential Decree it was officially declared as a 1 (one) day public religious holiday as of 9 April 2002 by President Megawati. The Indonesian government authorize only the first day of the Chinese New Year as a public religious holiday and it is specifically designated only for Chinese people. In Indonesia, the first day of the Chinese New Year is recognized as a part of the celebration of the Chinese religion and tradition of Chinese community. There are no other official or unofficial of the Chinese New Year as a public holiday. The remaining 14 days are celebrated only by ethnic Chinese families. In Indonesia, the Chinese Year is named as a year of Kǒngzǐ (孔子) or Kongzili in Bahasa Indonesia. Every year, the Ministry of Religious Affairs (Kementerian Agama Republik Indonesia) set the specific date of religious holiday based on input from religious leaders. The Chinese New Year is the only national religious holiday in Indonesia that was enacted specifically with the Presidential Decree, in this case with the Keputusan Presiden Republik Indonesia (Keppres RI) No 19 Tahun 2002 dated on 9 April 2002. The celebration of the Chinese New Year as a religious holiday is specifically intended only for Chinese People in Indonesia (tradisi masyarakat Cina yang dirayakan secara turun temurun di berbagai wilayah di Indonesia, dan umat Agama Tionghoa) and it is not intended to be celebrated by Indonesian Indigenous Peoples or Masyarakat Pribumi Indonesia.

Big Chinese population cities and towns like Jakarta, Medan, Singkawang, Pangkal Pinang, Binjai, Bagansiapiapi, Tanjungbalai, Pematangsiantar, Selat Panjang, Tanjung Pinang, Batam, Ketapang and Pontianak always have its own New Year's celebration every years with parade and fireworks. A lot shopping malls decorated its building with lantern, Chinese words and lion or dragon with red and gold as main color. Lion dance is a common sight around Chinese houses, temples and its shophouses. Usually, the Buddhist, Confucian and Taoist Chinese will burn a big incense made by aloeswood with dragon-decorated at front of their house.The temple is open 24 hours at the first day, their also distributes a red envelopes and sometimes rice, fruits or sugar to the poor around.

Australia and New Zealand

With one of the largest Chinese populations outside of Asia, Sydney also claims to have the largest Chinese New Year Celebrations outside of Asia with over 600,000 people attending the celebrations in Chinatown annually. The events there span over three weeks including the launch celebration, outdoor markets, evening street food stalls, Chinese top opera performances, dragon boat races, a film festival and multiple parades that incorporate Chinese, Japanese, Korean people and Vietnamese performers. More than 100,000 people attend notably the main parade with over 3,500 performers. The festival also attracts international media coverage, reaching millions of viewers in Asia. The festival in Sydney is organized in partnership with a different Chinese province each year. Apart from Sydney, other state capital cities in Australia also celebrate Chinese New Year due to large number of Chinese residents. The cities include: Brisbane, Adelaide, Melbourne Box Hill and Perth. The common activities are lion dance, dragon dance, New Year market, and food festival. In the Melbourne suburb of Footscray, Victoria a Lunar New Year celebration initially focusing on the Vietnamese New Year has expanded into a celebration of the Chinese New Year as well as the April New Year celebrations of the Thais, Cambodians, Laotians and other Asian Australian communities who celebrate the New Year in either January/February or April.

The city of Wellington hosts a two-day weekend festival for Chinese New Year, and a one-day festival is held in Dunedin, centred on the city's Chinese gardens.

North America

Many cities in North America sponsor official parades for Chinese New Year. Among the cities with such parades are San Francisco, Los Angeles, New York City, Boston, Chicago, Mexico City, Toronto, and Vancouver. However, even smaller cities that are historically connected to Chinese immigration, such as Butte, Montana, have recently hosted parades.

New York

Multiple groups in New York City cooperate to sponsor a week-long Lunar New Year celebration. The festivities include cultural festival, music concert, fireworks on the Hudson River near the Chinese Consulate, and special exhibits.. One of the key celebrations is the Chinese New Year parade with floats and fireworks taking place along the streets in Lower Manhattan. In June 2015, New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio declared that the Lunar New Year would be made a public school holiday..

California

The San Francisco Chinese New Year Festival and Parade is the oldest and largest event of its kind outside of Asia, and the largest Asian cultural event in North America.

The festival incorporates Grant and Kearny Streets into its street festival and parade route, respectively. The use of these streets traces its lineage back to early parades beginning the custom in San Francisco. In 1849, with the discovery of gold and the ensuing California Gold Rush, over 50,000 people had come to San Francisco to seek their fortune or just a better way of life. Among those were many Chinese, who had come to work in the gold mines and on the railroad. By the 1860s, the residents of San Francisco's Chinatown were eager to share their culture with their fellow San Francisco residents who may have been unfamiliar with (or hostile towards) it. The organizers chose to showcase their culture by using a favorite American tradition – the parade. They invited a variety of other groups from the city to participate, and they marched down what today are Grant Avenue and Kearny Street carrying colorful flags, banners, lanterns, drums, and firecrackers to drive away evil spirits.

In San Francisco, over 100 units participate in the annual Chinese New Year Parade held since 1958. The parade is attended by some 500,000 people along with another 3 million TV viewers.

Europe

In London, the celebrations take place throughout Chinatown, Leicester Square and Trafalgar Square. Festivities include a parade, cultural feast, fireworks, concerts and performances. The celebration attracts between 300,000 and 500,000 people yearly according to the organisers.

In Paris, the celebrations have been held since the 1980s in several districts during one month with many performances and the main of the three parades with 40 groups and 4,000 performers is attended alone by more than 200,000 people in the 13th arrondissement.

India and Pakistan

Many celebrate the festival in Chinatown, Kolkata, India where a significant community of people of Chinese origin exists. In Kolkata, Chinese New Year is celebrated with lion and dragon dance.

In Pakistan, the Chinese New Year is also celebrated among the sizable Chinese expatriate community that lives in the country. During the festival, the Chinese embassy in Islamabad arranges various cultural events in which Pakistani arts and cultural organizations and members of the civil society also participate.

Greetings

The Chinese New Year is often accompanied by loud, enthusiastic greetings, often referred to as 吉祥話 (jíxiánghuà) in Mandarin or 吉利說話 (Kat Lei Seut Wa) in Cantonese, loosely translated as auspicious words or phrases. New Year couplets printed in gold letters on bright red paper, referred to as chunlian (春聯) or fai chun (揮春), is another way of expressing auspicious new year wishes. They probably predate the Ming dynasty (1368–1644), but did not become widespread until then. Today, they are ubiquitous with Chinese New Year.

Some of the most common greetings include:

- simplified Chinese: 新年快乐; traditional Chinese: 新年快樂; pinyin: Xīnniánkuàilè; Jyutping: san1 nin4 faai3 lok6; Pe̍h-ōe-jī: Sin-nî khòai-lo̍k; Hakka: Sin Ngen Kai Lok; Taishanese: Slin Nen Fai Lok. A more contemporary greeting reflective of Western influences, it literally translates from the greeting "Happy new year" more common in the west. But in northern parts of China, traditionally people say simplified Chinese: 过年好; traditional Chinese: 過年好; pinyin: Guònián Hǎo instead of simplified Chinese: 新年快乐; traditional Chinese: 新年快樂 (Xīnniánkuàile), to differentiate it from the international new year. And 過年好 (Guònián Hǎo) can be used from the first day to the fifth day of Chinese New Year. However, 過年好 (Guònián Hǎo) is considered very short and therefore somewhat discourteous.

Gong Hei Fat Choi at Lee Theatre Plaza, Hong Kong - simplified Chinese: 恭喜发财; traditional Chinese: 恭喜發財; pinyin: Gōngxǐfācái; Hokkien: Kiong hee huat chai (POJ: Kiong-hí hoat-châi); Cantonese: Gung1 hei2 faat3 coi4; Hakka: Gung hee fatt choi, which loosely translates to "Congratulations and be prosperous". Often mistakenly assumed to be synonymous with "Happy New Year", its usage dates back several centuries. While the first two words of this phrase had a much longer historical significance (legend has it that the congratulatory messages were traded for surviving the ravaging beast of Nian, in practical terms it may also have meant surviving the harsh winter conditions), the last two words were added later as ideas of capitalism and consumerism became more significant in Chinese societies around the world. The saying is now commonly heard in English speaking communities for greetings during Chinese New Year in parts of the world where there is a sizable Chinese-speaking community, including overseas Chinese communities that have been resident for several generations, relatively recent immigrants from Greater China, and those who are transit migrants (particularly students).

Numerous other greetings exist, some of which may be exclaimed out loud to no one in particular in specific situations. For example, as breaking objects during the new year is considered inauspicious, one may then say 歲歲平安 (Suìsuì-píng'ān) immediately, which means "everlasting peace year after year". Suì (歲), meaning "age" is homophonous with 碎 (suì) (meaning "shatter"), in the demonstration of the Chinese love for wordplay in auspicious phrases. Similarly, 年年有餘 (niánnián yǒu yú), a wish for surpluses and bountiful harvests every year, plays on the word yú that can also refer to 魚 (yú meaning fish), making it a catch phrase for fish-based Chinese new year dishes and for paintings or graphics of fish that are hung on walls or presented as gifts.

The most common auspicious greetings and sayings consist of four characters, such as the following:

- 金玉滿堂 Jīnyùmǎntáng – "May your wealth come to fill a hall"

- 大展鴻圖 Dàzhǎnhóngtú – "May you realize your ambitions"

- 迎春接福 Yíngchúnjiēfú – "Greet the New Year and encounter happiness"

- 萬事如意 Wànshìrúyì – "May all your wishes be fulfilled"

- 吉慶有餘 Jíqìngyǒuyú – "May your happiness be without limit"

- 竹報平安 Zhúbàopíng'ān – "May you hear that all is well"

- 一本萬利 Yīběnwànlì – "May a small investment bring ten-thousandfold profits"

- 福壽雙全 Fúshòushuāngquán – "May your happiness and longevity be complete"

- 招財進寶 Zhāocáijìnbǎo – "When wealth is acquired, precious objects follow"

These greetings or phrases may also be used just before children receive their red packets, when gifts are exchanged, when visiting temples, or even when tossing the shredded ingredients of yusheng particularly popular in Malaysia and Singapore. Children and their parents can also pray in the temple, in hopes of getting good blessings for the new year to come.

Children and teenagers sometimes jokingly use the phrase 恭喜發財,紅包拿來 (in Traditional Chinese; Simplified Chinese: 恭喜发财,红包拿来; Pinyin: gōngxǐfācái, hóngbāo nálái; Cantonese: 恭喜發財,利是逗來; Jyutping: gung1 hei2 faat3 coi4, lei6 si6 dau6 loi4), roughly translated as "Congratulations and be prosperous, now give me a red envelope!". In Hakka the saying is more commonly said as 'Gung hee fatt choi, hung bao diu loi' which would be written as 恭喜發財,紅包逗來 – a mixture of the Cantonese and Mandarin variants of the saying.

Back in the 1960s, children in Hong Kong used to say 恭喜發財,利是逗來,斗零唔愛 (Cantonese, Gung Hei Fat Choy, Lai Si Tau Loi, Tau Ling M Ngoi), which was recorded in the pop song Kowloon Hong Kong by Reynettes in 1966. Later in the 1970s, children in Hong Kong used the saying: 恭喜發財,利是逗來,伍毫嫌少,壹蚊唔愛 (Cantonese), roughly translated as, "Congratulations and be prosperous, now give me a red envelope, fifty cents is too little, don't want a dollar either." It basically meant that they disliked small change – coins which were called "hard substance" (Cantonese: 硬嘢). Instead, they wanted "soft substance" (Cantonese: 軟嘢), which was either a ten dollar or a twenty dollar note.

See also

- Overseas Chinese

- Lunar New Year fireworks display in Hong Kong

- The Birthday of Che Kung

- Other celebrations of Lunar New Year in China:

- Tibetan New Year (Losar)

- Mongolian New Year (Tsagaan Sar)

- Celebrations of Lunar New Year in other parts of Asia:

- Korean New Year (Seollal)

- Japanese New Year (Shōgatsu)

- Mongolian New Year (Tsagaan Sar)

- Vietnamese New Year (Tết)

- Similar Asian Lunisolar New Year celebrations that occur in April:

- Burmese New Year (Thingyan)

- Cambodian New Year (Chaul Chnam Thmey)

- Lao New Year (Pii Mai)

- Sri Lankan New Year (Aluth Avuruddu)

- Thai New Year (Songkran)

- Chinese New Year Gregorian Holiday in Malaysia

- Malaysia Chinese New Year

Notes

- simplified Chinese: 农历新年, 春节; traditional Chinese: 農曆新年, 春節; pinyin: nóng lì xīn nián

- simplified Chinese: 春节; traditional Chinese: 春節; pinyin: Chūn Jié

References

- "Asia welcomes lunar New Year". BBC. 1 February 2003. Retrieved 7 November 2008.

- And extremely rarely, 21 February, such as in 2033, the first occurrence since the 1645 calendar reform – Helmer Aslaksen, "The Mathematics of the Chinese Calendar"

- Roy, Christian (2005). Traditional Festivals: A Multicultural Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 320. ISBN 978-1-57607-089-5.

- "Chinese New Year 2011". VisitSingapore.com. Retrieved 2 November 2011.

- "Chinese New Year Celebrated in Grand Scale in Yangon". Mizzima.com. Retrieved 28 January 2019.

- "Philippines adds Chinese New Year to holidays". Yahoo News Philippines. 2 December 2011. Retrieved 29 June 2013.

- "Festivals, Cultural Events and Public Holidays in Mauritius". Mauritius Tourism Authority. Archived from the original on 11 February 2016. Retrieved 28 January 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Crabtree, Justina (16 February 2018). "As the Lunar New Year celebrations begin, CNBC looks at Chinatowns across the world". CNBC.

- "Happy Chinese New Year! The year of the Dog has begun". USA TODAY.

- "Chinese New Year and its effect on the world economy - The Boston Globe". BostonGlobe.com.

- "Chinese New Year". History. Retrieved 9 February 2013.

- "The Year of the Dog - Celebrating Chinese New Year 2018". EC Brighton. 2018-02-16. Retrieved 2018-11-13.

- ^ Aslaksen, Helmer (July 17, 2010), The Mathematics of the Chinese Calendar (PDF), National University of Singapore, p. 31

- Chiu, Lisa. "The History of Chinese New Year". About.com. Retrieved 8 February 2013.

- 中國古代歲首分那幾種?各以何為起點? [In ancient China, how to decide the starting point of a year?] (in Chinese). Central Weather Bureau. Retrieved 26 January 2017.

- "Chinese New Year Calendar". Chinese New Year. chinesenewyears.info. Retrieved August 2, 2017.

- See Chinese calendar for details and references.

- "The Origin of Lunar New Year and the legend of Nian". Ancient Origins. 31 January 2014. Retrieved 6 September 2015.

- "Embassy Holidays". Embassy of the United States: Bandar Seri Begawan, Brunei Darussalam. U.S. Department of State. Archived from the original on 13 May 2015. Retrieved 4 March 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - "General holidays for 2018". Hong Kong Government. Retrieved 16 February 2018.

- "National Public Holidays in Indonesia". AngloINFO, the global expat network: INDONESIA. AngloINFO Limited. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 4 March 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - "Holiday Schedule". Embassy of the United States: Jakarta, Indonesia. U.S. Department of State. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 4 March 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - "Public Holidays in 2019 Decree Law No. 60/2000 on Public Holidays". Macao SARG Portal. Macao SAR of the People's Republic of China. Retrieved 24 Jan 2019.

- "Public Holiday Calendar". TravelChinaGuide. Retrieved 30 January 2017.

- "Holiday Schedule". Embassy of the United States: Beijing, China. U.S. Department of State. Archived from the original on 16 March 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - "Jadual hari kelepasan am persekutuan 2012" [Federal Public Holiday Schedule 2012] (PDF) (in Malay). Putrajaya, Malaysia: Jabatan Perdana Menteri (Department of the Prime Minister). Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 March 2013. Retrieved 4 March 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - "HOLIDAYS". Embassy of the United States: Kuala Lumpur, Mayalsia. U.S. Department of State. Retrieved 29 January 2017.

- "Proclamation No. 831, s. 2014 by the President of the Philippines, Declaring the Regular Holidays, Special (Non-Working) Days, and Special Holiday (for all Schools) for the Year 2015" (Press release). Malacañang Palace, Manila: Official Gazette of the Philippines. 17 July 2014. Retrieved 3 May 2017.

- "Before You Go: Useful Information: Public Holidays". Taiwan, the heart of Asia. Tourism Bureau, Republic of China (Taiwan). 4 February 2015. Retrieved 4 March 2015.

Chinese Lunar year: Lunar New Year's Eve; 1st, 2nd, 3rd of the 1st month by lunar calendar