This is an old revision of this page, as edited by 72.144.246.19 (talk) at 01:21, 30 November 2006 (→Role in popular culture and avant-garde art). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 01:21, 30 November 2006 by 72.144.246.19 (talk) (→Role in popular culture and avant-garde art)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) For other uses, see Mona Lisa (disambiguation).| Painting information | ||

|---|---|---|

| Artist | - | |

| Title | - | |

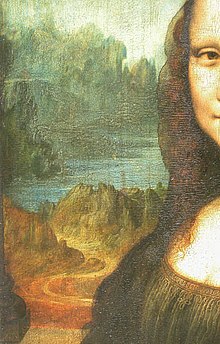

Mona Lisa, or La Gioconda (La Joconde), is a 16th-century oil painting on poplar wood by Leonardo da Vinci, and is arguably the most famous painting in the world. Few works of art have been subject to as much scrutiny, study, mythologizing and parody. It is owned by the French government and hangs in the Musée du Louvre in Paris.

The painting, a half-length portrait, depicts a woman whose gaze meets the viewer's with an expression often described as enigmatic.

Title of the painting

The title Mona Lisa stems from the Giorgio Vasari biography of Leonardo da Vinci, published 31 years after Leonardo's death. In it, he identified the sitter as Lisa Gherardini, the wife of wealthy Florentine businessman Francesco del Giocondo. "Mona" was a common Italian contraction of "madonna," meaning "my lady," the equivalent of the English "Madam," so the title means "Madam Lisa". In modern Italian the short form of "madonna" is usually spelled "Monna," so the title is sometimes given as Monna Lisa. This is rare in English, but more common in Romance languages. The alternative title La Gioconda is the feminine form of Giocondo. In Italian, giocondo also means 'light-hearted' ('jocund' in English), so "gioconda" means "light-hearted woman". Because of her smile, this version of the title plays on this double-meaning, as does the French "La Joconde".

Both Mona Lisa and La Gioconda became established as titles for the painting in the 19th century. Before these names became established, the painting had been referred to by various descriptive phrases, such as "a certain Florentine lady" and "a courtesan in a gauze veil."

History

16th century

Leonardo began painting the Mona Lisa in 1503 and, according to Vasari, completed it in four years.

Leonardo took the painting from Italy to France in 1516 when King François I invited the painter to work at the Clos Lucé near the king's castle in Amboise. The King bought the painting for 4,000 écus and kept it at Fontainebleau, where it remained until moved by Louis XIV.

Many art historians believe that after Leonardo's death the painting was cut down by having part of the panel at both sides removed. Originally there appear to have been columns on both sides of the figure, as can be seen in early copies. The edges of the bases can still be seen in the original. However, some art historians, such as Martin Kemp, argue that the painting has not been altered, and that the columns depicted in the copies were added by the copyists. There are also copies in which the figure appears nude.

Other versions

It has been suggested that Leonardo created more than one version of the painting. The owners of the version known as the Isleworth Mona Lisa claim that it is an original, though the great majority of art historians reject its authenticity. The same claim has been made for a version in the Vernon collection. Another version, dating from c.1616 was given in c.1790 to Joshua Reynolds by the Duke of Leeds in exchange for a Reynolds self-portrait. Reynolds thought it to be the real painting and the French one a copy, which has now been disproved. It is, however, useful in that it was copied when the original's colours were far brighter than they are now, and so it gives some sense of the original's appearance 'as new'. It is held in the stores of the Dulwich Picture Gallery. The nude versions have also led to speculation that they were copied from a lost Leonardo original depicting Lisa naked.

17th to 19th century

Louis XIV moved the painting to the Palace of Versailles. After the French Revolution, it was moved to the Louvre. Napoleon I had it moved to his bedroom in the Tuileries Palace; later it was returned to the Louvre. During the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–1871, it was moved from the Louvre to a hiding place elsewhere in France.

The painting was not well-known until the mid-19th century, when artists of the emerging Symbolist movement began to appreciate it, and associated it with their ideas about feminine mystique. Critic Walter Pater, in his 1867 essay on Leonardo, expressed this view by describing the figure in the painting as a kind of mythic embodiment of eternal femininity, who is "older than the rocks among which she sits" and who "has been dead many times and learned the secrets of the grave".

20th century to present

Theft

The painting's increasing fame was further emphasised when it was stolen on August 21, 1911. The next day, Louis Béroud, a painter, walked into the Louvre and went to the Salon Carré where the Mona Lisa had been on display for five years. However, where the Mona Lisa should have stood, in between Correggio's Mystical Marriage and Titian's Allegory of Alfonso d'Avalos, he found four iron pegs.

Béroud contacted the section head of the guards, who thought the painting was being photographed. A few hours later, Béroud checked back with the section head of the museum, and it was confirmed that the Mona Lisa was not with the photographers. The Louvre was closed for an entire week to aid in the investigation of the theft.

On September 6, avant-garde French poet Guillaume Apollinaire, who had once called for the Louvre to be "burnt down", was arrested and put in jail on suspicion of the theft. His friend Pablo Picasso was brought in for questioning, but both were later released. At the time, the painting was believed to be lost forever. It turned out that Louvre employee Vincenzo Peruggia stole it by entering the building during regular hours, hiding in a broom closet and walking out with it hidden under his coat after the museum had closed. Con-man Eduardo de Valfierno master-minded the theft, and had commissioned the French art forger Yves Chaudron to make copies of the painting so he could sell them as the missing original. Because he did not need the original for his con, he never contacted Peruggia again after the crime. After keeping the painting in his apartment for two years, Peruggia grew impatient and was caught when he attempted to sell it to a Florence art dealer; it was exhibited all over Italy and returned to the Louvre in 1913.

Second World War

During World War II the painting was again removed from the Louvre and taken to safety, first in Chateau Amboise, then in the Loc-Dieu Abbey and finally in the Ingres Museum in Montauban.

Post-war

In 1956, the lower part of the painting was severely damaged when someone doused it with acid. On December 30 of that same year, Ugo Ungaza Villegas, a young Bolivian, damaged the painting by throwing a rock at it. The result was a speck of pigment near Mona Lisa's left elbow. The painting is now covered with bulletproof security glass.

From December 14 1962 to March of 1963, the French government lent it to the United States to be displayed in New York City and Washington D.C. In 1974, the painting exhibited in Tokyo and Moscow before being returned to the Louvre.

Prior to the 1962-63 tour, the painting was assessed for insurance purposes at $100 million. According to the Guinness Book of Records, this makes the Mona Lisa the most valuable painting ever insured. As an expensive painting, it has only recently been surpassed (in terms of actual dollar price) by Gustav Klimt 's Adele Bloch-Bauer I, which was sold for $135 Million (£73 million) on 19 June, 2006. Although this figure is greater than that which the Mona Lisa was insured for, the comparison does not account for the change in prices due to inflation -- $100 million in 1962 is approximately $645 million in 2005 when adjusted for inflation using the US Consumer Price Index.

In 2004 experts from the National Research Council of Canada conducted a three-dimensional infrared scan. Because of the aging of the varnish on the painting it has been difficult to discern details. Data from the scan and infrared reflectography were later used by Bruno Mottin of the French Museums' "Center for Research and Restoration" to argue that the transparent gauze veil worn by the sitter is a guarnello, typically used by women while pregnant or just after giving birth. A similar guarnello was painted by Sandro Botticelli in his Portrait of Smeralda Brandini (1470), depicting a pregnant woman (on display in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London). Furthermore, this reflectography revealed that Mona Lisa's hair is not loosely hanging down, but seems attached at the back of the head to a bonnet or pinned back into a chignon and covered with a veil, bordered with a sombre rolled hem. In the 16th century, hair hanging loosely down on the shoulders, was the customary apanage of unmarried young women or prostitutes. This apparent contradiction with her status as a married woman has now been resolved.

Researchers also used the data to reveal details about the technique used and to predict that the painting will degrade very little if current conservation techniques are continued.

On April 6, 2005 — following a period of curatorial maintenance, recording, and analysis — the painting was moved, within the Louvre, to a new home in the museum's Salle des États. It is displayed in a purpose-built, climate-controlled enclosure behind bullet proof glass. The Mona Lisa has since undergone a major scientific observation, and it has been proved through infrared cameras she is wearing a bonnet and clenching her chair (something that da Vinci decided to change as an afterthought).

Identity of the model

Lisa Gherardini

Vasari identified the subject to be the wife of socially prominent Francesco del Giocondo, who was a silk merchant of Florence. Until recently, little was known about his third wife, Lisa Gherardini, except that she was born in 1479, raised at her family's Villa Vignamaggio in Tuscany and that she married del Giocondo in 1495.

In 2004 the Italian scholar Giuseppe Pallanti published Monna Lisa, Mulier Ingenua (literally '"Mona Lisa: Real Woman", published in English under the title Mona Lisa Revealed: The True Identity of Leonardo's Model). The book gathered archival evidence in support of the traditional identification of the model as Lisa Gherardini. According to Pallanti, the evidence suggests that Leonardo's father was a friend of del Giocondo. "The portrait of Mona Lisa, done when Lisa Gherardini was aged about 24, was probably commissioned by Leonardo's father himself for his friends as he is known to have done on at least one other occasion." Pallanti discovered that Lisa and Francesco had five children and that she outlived her husband. She lived at least into her 60s, though no record of her death was located.

In September 2006 Bruno Mottin argued that the guarnelo he studied using the 2004 scan data suggested that the painting dated from around 1503 and commemorated the birth of Lisa Gherardini's second son.

Other suggestions

Vasari, however, wrote about the portrait, and described it, without ever having seen it; the painting was already in France in Vasari's era. So various alternatives to the traditional sitter have been proposed. During the last years of his life, Leonardo spoke of a portrait "of a certain Florentine lady done from life at the request of the magnificent Giuliano de' Medici." No evidence has been found that indicates a link between Lisa Gherardini and Giuliano de' Medici, but then the comment could instead refer to one of the two other portraits of women executed by da Vinci. A later anonymous statement created confusion when it linked the Mona Lisa to a portrait of Francesco del Giocondo himself – perhaps the origin of the controversial idea that it is the portrait of a man.

Dr. Lillian Schwartz of Bell Labs suggests that the Mona Lisa is actually a self-portrait. She supports this theory with the results of a digital analysis of the facial features of Leonardo's face and that of the famous painting. When flipping a self-portrait drawing by Leonardo and then merging that with an image of the Mona Lisa using a computer, the features of the faces align perfectly. Critics of this theory suggest that the similarities are due to both portraits being painted by the same person using the same style. Additionally, the drawing on which she based the comparison may not be a self-portrait.

Serge Bramly, in his biography of Leonardo, discusses the possibility that the portrait depicts the artist's mother Caterina. This would account for the resemblance between artist and subject observed by Dr. Schwartz, and would explain why Leonardo kept the portrait with him wherever he travelled, until his death.

Art historians have also suggested the possibility that the Mona Lisa may only resemble Leonardo by accident: as an artist with a great interest in the human form, Leonardo would have spent a great deal of time studying and drawing the human face, and the face most often accessible to him was his own, making it likely that he would have the most experience with drawing his own features. The similarity in the features of the people depicted in paintings such as the Mona Lisa and St. John the Baptist may thus result from Leonardo's familiarity with his own facial features, causing him to draw other, less familiar faces in a similar light.

Maike Vogt-Lüerssen argues that the woman behind the famous smile is Isabella of Aragon, the Duchess of Milan. Leonardo was the court painter for the Duke Of Milan for 11 years. The pattern on Mona Lisa's dark green dress, Vogt-Lüerssen believes, indicates that she was a member of the house of Sforza. Her theory is that the Mona Lisa was the first official portrait of the new Duchess of Milan, which requires that it was painted in spring or summer 1489 (and not 1503). This theory is allegedly supported by another portrait of Isabella of Aragon, painted by Raphael, (Doria Pamphilj Gallery, Rome).

Aesthetics

Leonardo used a pyramid design to place the woman simply and calmly in the space of the painting. Her folded hands form the front corner of the pyramid. Her breast, neck, and face glow in the same light that softly models her hands. The light gives the variety of living surfaces an underlying geometry of spheres and circles.Leonardo refered to a seemingly simple formula for sitted female figure: the images of sitted Madonna, which were widely spread at the time. He effectively modificated this fomular in order to create the visual impression of distance between the sitter and the observer. The armrest of the chair functions as a dividing element between Mona Liza and us. The woman sits markedly upright with her arms folded, which is also a sign of her reserved posture. Only her gaze is fixed on the observer and seems to welcome him to this silent communication. Since the brightly lit face is practically framed with various much darker elements (hair, veil, shadows), the observer's attraction to Mona Lisa's face is brought to even greater extent. Thus, the composition of the figure evocates an ambiguos effect: we are attracted to this mystirious woman but have to stay at a distance as if she was a divine creature. There is no indication of an intimate dialogue between the woman and the observer like it is the case in the Portrait of Baltasare Castiglione (Louvre) pained by Raphael about ten years after Mona Lisa and undoubtedly influenced by Leonardo's portrait.

The painting was one of the first portraits to depict the sitter before an imaginary landscape. The enigmatic woman is portrayed seated in what appears to be an open loggia with dark pillar bases on either side. Behind her a vast landscape recedes to icy mountains. Winding paths and a distant bridge give only the slightest indications of human presence. The sensuous curves of the woman's hair and clothing, created through sfumato, are echoed in the undulating imaginary valleys and rivers behind her. The blurred outlines, graceful figure, dramatic contrasts of light and dark, and overall feeling of calm are characteristic of Leonardo's style. Due to the expressive synthesis that Leonardo achieved between sitter and the landscape it is arguable whether Mona Lisa should be considered as a portrait, for it represents rather an ideal than a real woman. The sense of overall harmony achieved in the painting—especially apparent in the sitter's faint smile— reflects Leonardo's idea of the cosmic link connecting humanity and nature, making this painting an enduring record of Leonardo's vision and genius.

Mona Lisa's smile has repeatedly been a subject of many - frequently rediculous - interpretations.Sigmund Freud interpreted the 'smile' as signifying Leonardo's erotic attraction to his dear mother; others have described it as both innocent and inviting. Many researchers have tried to explain why the smile is seen so differently by people. The explanations range from scientific theories about human vision to curious supposition about Mona Lisa's identity and feelings. Professor Margaret Livingstone of Harvard University has argued that the smile is mostly drawn in low spatial frequencies, and so can best be seen from a distance or with one's peripheral vision. Thus, for example, the smile appears more striking when looking at the portrait's eyes than when looking at the mouth itself. Christopher Tyler and Leonid Kontsevich of the Smith-Kettlewell Institute in San Francisco believe that the changing nature of the smile is caused by variable levels of random noise in human visual system. Dina Goldin, Adjunct Professor at Brown University, has argued that the secret is in the dynamic position of Mona Lisa's facial muscles, where our mind's eye unconsciously extends her smile; the result is an unusual dynamicity to the face that invokes subtle yet strong emotions in the viewer of the painting.

In late 2005, Dutch researchers from the University of Amsterdam ran the painting's image through an "emotion recognition" computer software developed in collaboration with the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. The software found the smile to be 83% happy, 9% disgusted, 6% fearful, 2% angry, less than 1% neutral, and not surprised at all. Rather than being a thorough analysis, the experiment was more of a demonstration of the new technology. The faces of ten women of Mediterranean ancestry were used to create a composite image of a neutral expression. Researchers then compared the composite image to the face in the painting. They used a grid to break the smile into small divisions, then checked it for each of six emotions: happiness, surprise, anger, disgust, fear, and sadness.

It is also notable that Mona Lisa has no visible facial hair at all - including eyebrows and eyelashes. Some researchers claim that it was common at this time for genteel women to pluck them off, since they were considered to be unsightly. Yet it is more reasonable to assume that Leonardo did not finish the painting, for almost all of his paintings are unfinished. Being a perfectionist he always tried to go one step further in improving his technique. Furthermore, other women of the time were predominantly portraited with eybrows. For modern viewers the missing eywbrows add to the slightly semi-abstract quality of the face though it was not Leonardo's aim.

The painting has been restored numerous times; X-ray examinations have shown that there are three versions of the Mona Lisa hidden under the present one. The thin poplar backing is beginning to show signs of deterioration at a higher rate than previously thought, causing concern from museum curators about the future of the painting.

Notes

- Vernon collection copy; Walters Gallery version

- http://www.lairweb.org.nz/leonardo/mona.html Leonardo da Vinci

- Charlotte Higgins, "Unveiled: early copy that reveals Mona Lisa as her creator intended", The Guardian, 23rd September 2006 (accessed on 23rd September 2006)

- http://www.nigel-cawthorne.com/projects.htm

- E.H. Net. What is its Relative Value in US Dollars. Accessed on June 20, 2006.

- CBC. (2006, September 26) Retrieved on September 27, 2006.

- CNN. (2006, September 26). The Mona Lisa studied in 3D Retrieved on September 25, 2006.

- Edmonton Journal (September 23) Retrieved on September 27, 2006

- BBC News. (2005, April 6). Mona Lisa gains new Louvre home. Retrieved on June 20, 2006.

- Pallanti, G. (2006). Mona Lisa revealed : The true identity of Leonardo's model. Milan: Skira. ISBN 88-7624-659-2

- Johnston, B. (2004, August 1). Riddle of Mona Lisa is finally solved. Telegraph.co.uk. Retrieved on June 20, 2006.

- CNN. (2006, September 26). The Mona Lisa studied in 3D Retrieved on September 25, 2006.

- Edmonton Journal (September 23) Retrieved on September 27, 2006

- Freud, S. Leonardo da Vinci and a memory of his childhood. Retrieved on June 20, 2006.

- BBC News. (2003, February 18). Mona Lisa smile secrets revealed. Retrieved on June 20, 2006.

- Cohen, P. (2004, June 23). Noisy secret of Mona Lisa's smile. New Scientist. Journal reference: Vision Research (vol 44, p 1493). Retrieved on June 20, 2006.

- Goldin, D. (2002, December). Mona Lisa's Secret Revealed. November 1, 2002 draft. Brown University Faculty Bulletin. Retrieved on June 20, 2006.

- Turudich, D. & Welch, L. (2003). Plucked, shaved and braided: Medieval and renaissance beauty and grooming practices 1000-1600. Leicester, England: Streamline Press. ISBN 1-930064-08-X

- McMullen, R. (1975). Mona Lisa: The picture and the myth. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-333-19169-2

See also

External links

- The Mona Lisa Exposed, an ad-supported Tufts University student website dedicated to the Mona Lisa painting

- Theft of the Mona Lisa, from the PBS website for Treasures Of The World

- Aging Mona Lisa worries Louvre, an April 2004 BBC article

- The Mona Lisa, another BBC article

- The Mona Lisa photos & photos from Louvre

- Mona Lisa (Zoomable Version)

- Leonardo da Vinci, Gallery of Paintings and Drawings

- Unmasking the Mona Lisa: Expert claims to have discovered da Vinci's technique

- Who is Mona Lisa? Historical Facts versus Conjectures

- Mona Lisa's voice simulated

- "Mona Lisa had a makeover, 3D images reveal", Cosmos magazine, September 2006