This is an old revision of this page, as edited by 141.219.41.163 (talk) at 16:39, 8 January 2005 (rv). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 16:39, 8 January 2005 by 141.219.41.163 (talk) (rv)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)Surrealism is a movement that aims for the liberation of the mind by emphasizing the critical and imaginative powers of the subconscious, and seeking the total integration of such "contradictory states" as dream and waking into an absolute, or "surreality." Surrealism is often misinterpreted as an artistic movement, though nearly every primary source either explicitly or implicitly (in not focussing on art) contradictions this; it has transformed visual art, writing, film, music, and political thought, not to mention everyday life. Though the terms "surrealism," "surreal" and the like are often used loosely to refer to things departing from what is generally regarded as "real," or to "odd" juxtapositions, surrealism has more or less bitterly denounced this practice. Surrealism remains an active movement today.

History

The term surrealism was coined by Guillaume Apollinaire to describe the Jean Cocteau/Erik Satie/Pablo Picasso/Léonide Massine collaboration Parade (1917) in the program notes: "From this new alliance, for until now stage sets and costumes on one side and choreography on the other had only a sham bond between them, there has come about, in Parade, a kind of super-realism (sur-réalisme), in which I see the starting point of a series of manifestations of this new spirit (esprit nouveau)."

While related to Dada, from which many of its initial members came, surrealism is significantly broader in scope. Dada was primarily rooted in negative response to First World War, which Dada viewed as demonstrating the catastrophic hypocrisy and failure of Western civilisation. Surrealism, however, advocates a positive programme open to the full range of imagination. Its advocates argue that it is a view that the world can be changed and transformed into a fertile crescent of freedom, love, and poetry.

Surrealism is connected with the theories of Sigmund Freud. Part of its diagnosis of the "problems" of realism and capitalist civilisation is the restrictive overlay of false rationality, including social and academic convention, on the free functioning of the instinctual creative urges within the mind.

André Breton's Surrealist Manifesto of 1924 and the publication of the magazine La Révolution Surréaliste ("The Surrealist Revolution") marked the beginning of the movement as a public agitation. In the manifesto of 1924 Breton defines surrealism as "pure psychic automatism" with automatism being spontaneous creative production without conscious moral or aesthetic self-censorship. By Breton's admission, however, as well as by the subsequent development of the movement, this was a definition capable of considerable expansion. Breton also wrote the following dictionary and encyclopedia definitions:

- "SURREALISM, n. Pure psychic automatism, by which one proposes to express, either verbally, or in writing, or by any other manner, the real functioning of thought. Dictation of thought in the absence of all control exercised by reason, outside of all aesthetic and moral preoccupation.

- ENCYCLOPEDIA. Philosophy. Surrealism is based on the belief in the superior reality of certain forms of previously neglected associations, in the omnipotence of dream, in the disinterested play of thought. It tends to ruin once and for all all other psychic mechanisms and to substitute itself for them in solving all the principal problems of life."

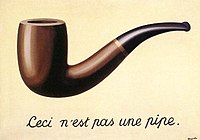

Breton and Philippe Soupault wrote the first automatic book, Les Champs Magnetiques, in 1919. Later, automatic drawing was developed by André Masson, and automatic drawing and painting, as well as other automatist methods, such as decalcomania, frottage, fumage, grattage and parsemage became significant parts of surrealist practice. (Automatism was later adapted to the computer.) Many of the popular artists in Paris throughout the 1920s and 1930s were surrealists, including René Magritte, Joan Miró, Max Ernst, Salvador Dalí, Alberto Giacometti, Valentine Hugo, Meret Oppenheim, Man Ray, and Yves Tanguy. Games such as the exquisite corpse also assumed a great importance in surrealism. Although sometimes considered exclusively French, surrealism was in fact international from the beginning, with both the Belgian and Czech groups developing early; the Czech group continues uninterrupted to this day. In fact, some of the most significant surrealist theorists and the most radical of surrealist methods have hailed from countries other than France. For example, the technique of cubomania was invented by Romanian surrealist Gherasim Luca.

In popular culture, particularly in the United States of America, surrealism in the visual arts is probably most often associated with the paintings of Salvador Dalí. Dalí was active in surrealism from 1929 to 1936, and gave the movement what he called the Paranoiac-critical method, which was well received at the time. From the late 1930s there are many, often quite vehement, surrealist denunciations of Dali. Most members of the movement have found Dalí's painting to have had little significance for surrealism, and Dalí to have moved further and further away from the movement. (However, there have been some, such as André Thirion, who have taken a more measured view.)

The 1960s saw an expansion of surrealism with the founding of The West Coast Surrealist Group as recognized by Andre Breton's personal assistant Jose Pierre and also The Surrealist Movement in the United States, and surrealist groups around the world, including many in areas in which surrealism had not previously existed, such as the Surrealist Group of Pakistan.

Surrealism in the Visual Arts

In general usage, the term Surrealism is more often applied to manifestations of surrealism in the visual arts (even though some of these, such as the works of Jean Cocteau, are definitely viewed by surrealists as non-surrealist and even anti-surrealist). However, it was debated at the outset whether there could even be such a thing as surrealist painting, there have been many surrealists who never had any activity in the visual arts, there has been much surrealist activity that is extra-artistic, and the entire movement is indeed founded on the supersession of such categories.

Impact of Surrealism

While surrealism is typically associated with the arts, it has been said to transcend them; surrealism has had an impact in many other fields. In this sense, surrealism does not specifically refer only to self-identified "surrealists", but to a range of creative acts of revolt and efforts to liberate the imagination. In surrealist writings the works of a number of artists have been called "objectively surrealist," that is, they are surrealist even though the artist may not identify them as such and perhaps even "despite themselves."

Though some find similarities to automatism in such practices as "brainstorming," surrealists would identify the comparison as extremely superficial and not taking into account the intensity of automatism, as well as some other factors.

In addition to Surrealist ideas finding their genesis in the ideas of Hegel, Marx and Freud, surrealism is seen by its advocates as being inherently dynamic and claims to be dialectic in its thought. Surrealist groups have also drawn on sources as seemingly diverse as Bugs Bunny, comic strips, the obscure poet Samuel Greenberg and the hobo writer and humourist T-Bone Slim. One might say that surrealist strands may be found in movements such as Free Jazz (Don Cherry, Sun Ra, etc.) and even in the daily lives of people in confrontation with limiting social conditions. Thought of as the effort of humanity to liberate the imagination as an act of insurrection against society, surrealism dates back to, or finds precedents in, the alchemists, possibly Dante, various heretical groups, Hieronymus Bosch, Marquis de Sade, Charles Fourier, Comte de Lautreamont and Arthur Rimbaud. Some people believe that "Non-western" cultures also provide a continued source of inspiration for surrealist activity because some may strike up a better balance between instrumental reason and the imagination in flight than Western culture.

Some artists, such as H.R. Giger in Europe, who won an Academy Award for his stage set, and who also designed the "creature," in the movie Alien, have been popularly called "surrealists," though Giger is a visionary artist and does not claim to be surrealist. The Society for the Art of Imagination has come in for particularly bitter criticism from the surrealist movement (although this criticism has been characterized by at least one anonymous individual as coming from "the Marxists surrealist groups, who maintain small contingents worldwide;" he has also pointed out what he considers the hypocrisy of any surrealist criticism of the Society for the Art of Imagination given that Kathleen Fox designed the cover of issue 4 of the bulletin of the Groupe de Paris du Mouvement Surrealiste and also participated in the 2003 "Brave Destiny" show at the Williamsburg Art & Historical Center." Though some presented "Brave Destiny" as the largest-ever exhibit of surrealist artists, the show was officially billed as exhibiting "Surrealism, Surreal/Conceptual, Visionary, Fantastic, Symbolism, Magic Realism, the Vienna School, Neuve Invention, Outsider, Naïve, the Macabre, Grotesque and Singulier Art.")

Surrealist music

Although Breton initially responded rather negatively to the subject of music with his essay "Silence is Golden," later surrealists have been interested in, and found parallels to surrealism in, the improvisation of jazz (as alluded to above), and the blues (surrealists such as Paul Garon have written articles and full-length books on the subject). Jazz and blues musicians have occasionally reciprocated this interest; for example, the 1976 World Surrealist Exhibition included such performances. (Surrealists have also analysed reggae and, later, rap, and some rock bands such as The Psychedelic Furs.) In addition to musicians who have been influenced by surrealism (including some minor influence in rock -- the title of the 1967 psychedelic Jefferson Airplane album Surrealistic Pillow was obviously inspired by the movement, and some people claim that Frank Zappa's 1969 album Uncle Meat was a "surrealist record" -- particularly hardcore), such as the experimental group Nurse With Wound (whose album title "Chance meeting on a dissecting table of a sewing machine and umbrella" is taken from a line in Lautreamont's "Maldoror"), surrealist music has included such explorations as those of Hal Rammel.

Surrealist film

Surrealist films such as Un chien andalou and L'Âge d'Or by Luis Buñuel have also been produced.

Surrealist and film theorist Robert Benayoun has written books on Tex Avery, Woody Allen, Buster Keaton and the Marx Brothers.

Some have described David Lynch as a surrealist filmmaker. He has never participated in the surrealist movement or in any surrealist activity, but there are arguably some aspects of many of his films that are of surrealist interest.

Surrealist television

Some have found the television series The Prisoner to be of surrealist interest.

Related reading

- André Breton, "Conversations: The Autobiography of Surrealism" (Gallimard 1952) (Paragon House English rev. ed. 1993). ISBN 1569249709.

- "What is Surrealism?: Selected Writings of André Breton" (edited and with an Introduction by Franklin Rosemont). ISBN 0873488229.

- André Breton, "Manifestoes of Surrealism" containing the 1, 2 and introduction to a possible 3 Manifesto, and in addition the novel "The Soluble Fish" and political aspects of the surrealist movement. ISBN 0472179004.

- Surrealist Subversions: The Surrealist Movement in the United States (edited with an introduction by Ron Sakolsky). ISBN 1570271224.

- Rosemont, Franklin, Surrealism and Its Popular Accomplices. San Francisco, CA: City Lights Books (1980). ISBN 087286121X.

- Brotchie, Alastair and Gooding, Mel, eds. A Book of Surrealist Games. Berkeley, CA: Shambhala (1995). ISBN 1570620849.

See also

- Aerography

- Blue Feathers

- Camus, Albert

- Cacophony Society

- Cut-up technique

- Dada

- Exquisite corpse game

- Fluxus

- Fumage

- Giorgio Chirico

- Hysterical realism

- mail art

- Paranoiac-critical method

- Post-surrealism

- Situationism

- surautomatism

Source

- Guillaume Appollinaire (1917, 1991). "Program Note for Parade", printed in Oeuvres en prose complètes, 2:865-866, Pierre Caizergues and Michel Décaudin, eds. Paris: Éditions Gallimard.

- André Breton. The Abridged Dictionary of Surrealism, reprinted in:

- Marguerite Bonnet, ed. (1988). Oeuvres complètes, 1:328. Paris: Éditions Gallimard.

External links

- Manifesto of Surrealism by André Breton

- "What is Surrealism?" Lecture by Breton, Brussels 1934

- Surrealism on the Web: A collection of information on surrealism, surreal artists, and surreal websites.

- Surrealist Groups