This is an old revision of this page, as edited by 140.198.86.89 (talk) at 21:16, 4 December 2006 (→Character issues). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 21:16, 4 December 2006 by 140.198.86.89 (talk) (→Character issues)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)

The U.S. presidential election of 1992 featured a three-way battle between Republican George Bush, the incumbent President; Democrat Bill Clinton, the governor of Arkansas; and independent candidate Ross Perot, a Texas businessman. Bush had alienated much of his conservative base by breaking his 1988 campaign pledge against raising taxes, the economy had sunk into recession, and his perceived best strength, foreign policy, was regarded as much less important following the collapse of the Soviet Union and the relatively peaceful climate in the Middle East following the defeat of Iraq in the Gulf War. Clinton successfully capitalized on these weaknesses by running as a centrist New Democrat and won the presidency.

Nominations

Republican Party nomination

Despite an early challenge by conservative journalist Pat Buchanan, President George H. W. Bush and Vice President Dan Quayle easily won renomination by the Republican Party. However, the success of the conservative opposition forced President Bush to move further to the right than in 1988, and to incorporate many socially conservative planks in the party platform. Bush allowed Buchanan to give the keynote address at the Republican National Convention in Houston, and his culture war speech alienated many moderates. David Duke also entered the Republican primary, but performed poorly at the polls.

Despite intense pressure on the Buchanan delegates to relent, the tally for president went like this:

- George H.W. Bush 2166

- Patrick J. Buchanan 18

- former ambassador Alan Keyes 1

Vice President Dan Quayle was renominated by voice vote.

Democratic Party nomination

In 1991, President Bush had high popularity ratings in the wake of the Gulf War. Many well-known Democrats, including House Majority Leader Dick Gephardt of Missouri and Governor Mario Cuomo of New York, considered the race unwinnable and did not run for the nomination. Those that did run included several less-well-known candidates:

- Larry Agran, mayor of Irvine, California

- Jerry Brown, former governor of California and candidate for the 1976 and 1980 nominations

- Bill Clinton, governor of Arkansas

- Tom Harkin, U.S. senator from Iowa

- Bob Kerrey, U.S. senator from Nebraska

- Tom Laughlin, film actor and director from California

- Eugene McCarthy, former U.S. senator from Minnesota and candidate for the 1968 and 1972 nominations

- Paul Tsongas, former U.S. senator from Massachusetts

- Douglas Wilder, governor of Virginia

- Charles Woods, millionaire Alabama businessman and frequent candidate for U.S. Senate and for Governor of Alabama

Clinton, a Southerner with experience governing a more conservative state, was able to finish the primaries positioned as a centrist New Democrat. Clinton's first foray into national politics occurred when he was enlisted to speak at the 1988 Democratic National Convention, introducing candidate Michael Dukakis. Clinton's address, scheduled to last 15 minutes, lasted over half an hour. Toward the end of the speech, conventioneers began chanting “Get off!” The speech drew cheers only when Clinton uttered the words, “in conclusion.” Clinton later poked fun at himself on Johnny Carson's Tonight Show by saying that the speech "had not been my finest hour, not even my finest hour and a half."

Four years later, Clinton prepared for a run in 1992 amidst a crowded field seeking to beat the incumbent President George H. W. Bush. In the aftermath of the Persian Gulf War, Bush seemed unbeatable but a deep economic recession spurred Democrats on. Tom Harkin won his native Iowa without much surprise. Clinton, meanwhile, was still a relatively unknown national candidate before the primary season when a woman named Gennifer Flowers appeared in the press to reveal allegations of an affair. Clinton sought damage control by appearing on 60 Minutes with his wife, Hillary Rodham Clinton, for an interview with Steve Kroft. Paul Tsongas won the primary in neighboring New Hampshire but Clinton's second place finish - strengthened by Clinton's speech labeling himself "The Comeback Kid" - reenergized his campaign. Clinton swept nearly all of the Super Tuesday primaries, making him the solid front runner. Jerry Brown, however, began to run a surprising insurgent campaign, particularly through use of a 1-800 number to receive grassroots funding. Brown scored surprising wins in Connecticut and Colorado and seemed poise to overtake Clinton but a series of controversial missteps set Brown back and Clinton effectively won the Democratic Party's nomination after winning the New York Primary in early April.

The convention met in New York City, and the official tally was:

- Bill Clinton 3372

- Jerry Brown 596

- Paul Tsongas 289

- Penn. Gov.Robert Casey 10

- Rep. Pat Shroeder 5

- Larry Agran 3

- Al Gore 1

Clinton chose U.S. Senator Albert A. Gore Jr. (D-Tennessee) to be his running mate on July 9 1992. Initially this decision sparked criticism from strategists due to the fact that Gore was from Clinton's neighboring state of Tennessee which would go against the popular strategy of balancing a Southern candidate with a Northern partner. In retrospect, many now view Gore as a helpful factor in the 1992 campaign for providing the ticket with a consistent centrist, relatively youthful theme of change.

The Democratic Convention in New York City was essentially a solidification of the party around Clinton and Gore, though there was controversey over whether Jerry Brown would be allowed to speak. Brown did indeed speak and ultimately endorsed the Clinton campaign.

More: 1992 Democratic presidential primary.

Other nominations

The public's unease about the deficit and fears of professional politicians allowed the independent candidacy of billionaire Texan Ross Perot to explode on the scene in the most dramatic fashion—at one point Perot was the leader in the polls. Perot crusaded against the national debt, tapping vague fears of deficits that has been part of American political rhetoric since the 1790s. His volunteers succeeded in collecting enough signatures to get his name on the ballot in all 50 states. In June, Perot led the national public opinion polls with support from 39% of the voters (versus 31% for Bush and 25% for Clinton). Perot severely damaged his credibility by dropping out of the presidential contest in July and remaining out of the race for several weeks before re-entering. He compounded this damage by eventually claiming, without evidence, that his withdrawal was due to Republican operatives attempting to disrupt his daughter's wedding. His presence, however, ensured that economic issues remained at the center of the national debate.

The 1992 campaign also marked the unofficial entry of Ralph Nader into presidential politics. Despite the advice of several liberal and environmental groups, Nader did not formally run. Rather, he tried to make an impact in the New Hampshire primaries, urging members of both parties to write-in NONE OF THE ABOVE. As a result, several thousand Democrats and Republicans wrote-in Nader's own name. Though thought to be a left-wing politician, Nader curiously received more votes from Republicans than Democrats.

General election

Campaign

Every U.S. presidential election campaign is an amalgam of issues, images and personality; and despite the intense focus on the country's economic future, the 1992 contest was no exception. The Bush reelection effort was built around a set of ideas traditionally used by incumbents: experience and trust. It was in some ways a battle of generations. George H. W. Bush, 68, probably the last president to have served in World War II, faced a young challenger in Bill Clinton who, at age 46, had never served in the military and had participated in protests against the Vietnam War. In emphasizing his experience as president and commander-in-chief, Bush also drew attention to what he characterized as Clinton's lack of judgment and character.

For his part, Bill Clinton organized his campaign around another of the oldest and most powerful themes in electoral politics: change. As a youth, Clinton had once met President John F. Kennedy, and in his own campaign 30 years later, much of his rhetoric challenging Americans to accept change consciously echoed that of Kennedy in his 1960 campaign.

As Governor of Arkansas for 12 years, then Governor Clinton could point to his experience in wrestling with the very issues of economic growth, education and health care that were, according to public opinion polls, among President Bush's chief vulnerabilities. Where President Bush offered an economic program based on lower taxes and cuts in government spending, Governor Clinton proposed higher taxes on the wealthy and increased spending on investments in education, transportation and communications that, he believed, would boost the nation's productivity and growth and thereby lower the deficit. Similarly, Governor Clinton's health care proposals to control costs called for much heavier involvement by the federal government than President Bush's. During the campaign, Governor Clinton hardened a soft public image when he controversially traveled back to Arkansas to oversee the execution of functionally retarded inmate Ricky Ray Rector.

The slogan “It's the economy, stupid” (coined by Democratic strategist James Carville) was used internally in the Clinton campaign to remind staffers to keep their focus on Bush's economic performance and not get distracted by other issues. Governor Clinton successfully hammered home the theme of change throughout the campaign, as well as in a round of three televised debates with President Bush and Ross Perot in October.

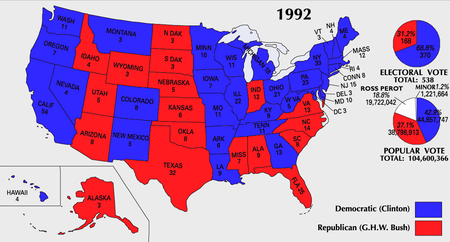

Results

On November 3, Bill Clinton won election as the 42nd President of the United States by a wide margin in the U.S. Electoral College, despite receiving only 43 percent of the popular vote. It was the first time since 1968 that a candidate won the White House with under 50 percent of the popular vote. The state of Arkansas was the only state in the entire country that gave the majority of its vote to a single candidate; the rest were won by pluralities of the vote.

Independent candidate Ross Perot received 19,741,065 popular votes for President. The billionaire used his own money to advertise extensively, and is the only third-party candidate ever allowed into the nationally televised presidential debates with both major party candidates. (Independent John Bayard Anderson debated Republican Ronald Reagan in 1980, but without Democrat Jimmy Carter who had refused to appear in a three-man debate.) Perot was ahead in the polls for a period of almost two months - not accomplished by an independent candidate in almost 100 years. Perot lost much of his support when he temporarily withdrew from the election, only to soon after again declare himself a candidate.

Perot's almost 19% of the popular vote made him the most successful third-party presidential candidate in terms of popular vote since Theodore Roosevelt in the 1912 election. Some conservative analysts believe that Perot acted as a spoiler in the election, primarily drawing votes away from Bush and allowing Clinton to win many states with less than a majority of votes. However, exit polling indicated that Perot voters would have split their votes fairly evenly among Clinton and Bush had Perot not been in the race, and an analysis by FairVote - Center for Voting and Democracy suggested that, while Bush would have won more electoral votes with Perot out of the race, he would not have gained enough to reverse Clinton's victory.

Perot managed to finish ahead of one of the two major party candidates in two states: In Maine, Perot received 30.44% of the vote to Bush's 30.39% (Clinton won Maine with 38.77%); In Utah, Perot received 27.34% of the vote to Clinton's 24.65% (Bush won Utah with 43.36%).

Analysis

Several factors made the results possible. First, the campaign came on the heels of the recession of 1990-91. While in historical terms the recession was mild and actually ended before the election, the resulting job loss (especially among middle managers not yet accustomed to white collar downsizing) fueled strong discontent with Bush, who was successfully portrayed as aloof, out of touch, and overly focused on foreign affairs. Highly telegenic, Clinton was perceived as sympathetic, concerned, and more in touch with ordinary families.

Second was the decision by Bush to accept a tax increase. Pressured by rising budget deficits, increased demand for entitlement spending and reduced tax revenues (each a consequence of the recession) Bush agreed to a budget compromise with Congress (where rival Democrats held the majority). Not having been in Congress at the time, Clinton was able to effectively condemn the tax increase on both its own merits and as a reflection of Bush's honesty. Effective Democratic TV ads were aired showing a clip of Bush's infamous 1988 campaign speech in which he promised "Read my lips ... No new taxes." In a semantic irony, President Bush did not add new taxes, only increasing existing taxes, but the implied meaning was clear, as he had explicitly stated in the speech, "My opponent won't rule out raising taxes. But I will. The Congress will push me to raise taxes and I'll say no."

Most importantly, Bush's coalition was in disarray, for both the aforementioned reasons and for unrelated reasons. The end of the Cold War allowed old rivalries among conservatives to re-emerge and meant that other voters focused more on domestic policy, to the detriment of Bush, a social and fiscal moderate. Ross Perot — like Bush a conservative Texas businessman, but unlike Bush playing to concerns about the budget deficit — siphoned crucial moderate and conservative votes from Bush. Perot, in gaining a higher percentage of the popular vote than any third-party presidential candidate in eighty years, allowed Clinton to win with the smallest plurality in the same time period. Despite a fractious and ideologically diverse party, Clinton was able to successfully court all wings of the Democratic party, even where they conflicted. To garner the support of moderates and conservative Democrats, he attacked Sister Souljah, a little-known rap musician whose lyrics Clinton condemned. Clinton could also point to his moderate, New Democrat record as Governor of Arkansas. More liberal Democrats were impressed by Clinton's academic credentials, 60's-era protest record, and support for social causes such as a woman's right to abortion. Supporters remained energized and confident, even in times of scandal or missteps.

Clinton's election ended an era in which the Republican party had controlled the White House for 12 consecutive years, and for 20 of the previous 24 years. That election also brought the Democrats full control of the political branches of the federal government, including both houses of U.S. Congress as well as the presidency, for the first time since the administration of the last Democratic president, Jimmy Carter.

| Presidential candidate | Party | Home state | Popular vote | Electoral vote |

Running mate | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count | Percentage | Vice-presidential candidate | Home state | Electoral vote | ||||

| William Jefferson Clinton | Democratic, Liberal (NY) | Arkansas | 44,909,806 | 43.0% | 370 | Albert Arnold Gore, Jr. | Tennessee | 370 |

| George Herbert Walker Bush | Republican, Conservative (NY), Right To Life (NY) | Texas | 39,104,550 | 37.4% | 168 | James Danforth Quayle | Indiana | 168 |

| Henry Ross Perot | (none) | Texas | 19,743,821 | 18.9% | 0 | James Bond Stockdale | California | 0 |

| Andre V. Marrou | Libertarian | 290,087 | 0.3% | 0 | Nancy Lord | Nevada | 0 | |

| James “Bo” Gritz | Populist | 106,152 | 0.1% | 0 | Cy Minett | 0 | ||

| Other | 269,507 | 0.3% | — | Other | — | |||

| Total | 104,423,923 | 100% | 538 | 538 | ||||

| Needed to win | 270 | 270 | ||||||

Source (Popular Vote): Leip, David. "1992 Presidential Election Results". Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections. Retrieved August 7, 2005. {{cite web}}: Check date values in: |access-date= (help)

Source (Electoral Vote): "Electoral College Box Scores 1789–1996". National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved August 7, 2005. {{cite web}}: Check date values in: |access-date= (help)

Voter demographics

| THE PRESIDENTIAL VOTE IN SOCIAL GROUPS (IN PERCENTAGES) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % of 1992 total vote |

3-party vote | ||||||

| 1992 | 1996 | ||||||

| Social group | Clinton | Bush | Perot | Clinton | Dole | Perot | |

| Total vote | 43 | 37 | 19 | 49 | 41 | 8 | |

| Party and ideology | |||||||

| 2 | Liberal Republicans | 17 | 54 | 30 | 44 | 48 | 9 |

| 13 | Moderate Republicans | 15 | 63 | 21 | 20 | 72 | 7 |

| 21 | Conservative Republicans | 5 | 82 | 13 | 6 | 88 | 5 |

| 4 | Liberal Independents | 54 | 17 | 30 | 58 | 15 | 18 |

| 15 | Moderate Independents | 43 | 28 | 30 | 50 | 30 | 17 |

| 7 | Conservative Independents | 17 | 53 | 30 | 19 | 60 | 19 |

| 13 | Liberal Democrats | 85 | 5 | 11 | 89 | 5 | 4 |

| 20 | Moderate Democrats | 76 | 9 | 15 | 84 | 10 | 5 |

| 6 | Conservative Democrats | 61 | 23 | 16 | 69 | 23 | 7 |

| Gender and marital status | |||||||

| 33 | Married men | 38 | 42 | 21 | 40 | 48 | 10 |

| 33 | Married women | 41 | 40 | 19 | 48 | 43 | 7 |

| 15 | Unmarried men | 48 | 29 | 22 | 49 | 35 | 12 |

| 20 | Unmarried women | 53 | 31 | 15 | 62 | 28 | 7 |

| Race | |||||||

| 83 | White | 39 | 40 | 20 | 43 | 46 | 9 |

| 10 | Black | 83 | 10 | 7 | 84 | 12 | 4 |

| 5 | Hispanic | 61 | 25 | 14 | 72 | 21 | 6 |

| 1 | Asian | 31 | 55 | 15 | 43 | 48 | 8 |

| Religion | |||||||

| 46 | White Protestant | 33 | 47 | 21 | 36 | 53 | 10 |

| 29 | Catholic | 44 | 35 | 20 | 53 | 37 | 9 |

| 3 | Jewish | 80 | 11 | 9 | 78 | 16 | 3 |

| 17 | Born Again, religious right | 23 | 61 | 15 | 26 | 65 | 8 |

| Age | |||||||

| 17 | 18–29 years old | 43 | 34 | 22 | 53 | 34 | 10 |

| 33 | 30–44 years old | 41 | 38 | 21 | 48 | 41 | 9 |

| 26 | 45–59 years old | 41 | 40 | 19 | 48 | 41 | 9 |

| 24 | 60 and older | 50 | 38 | 12 | 48 | 44 | 7 |

| Education | |||||||

| 6 | Not a high school graduate | 54 | 28 | 18 | 59 | 28 | 11 |

| 24 | High school graduate | 43 | 36 | 21 | 51 | 35 | 13 |

| 27 | Some college education | 41 | 37 | 21 | 48 | 40 | 10 |

| 26 | College graduate | 39 | 41 | 20 | 44 | 46 | 8 |

| 17 | Post graduate education | 50 | 36 | 14 | 52 | 40 | 5 |

| Family income | |||||||

| 11 | Under $15,000 | 58 | 23 | 19 | 59 | 28 | 11 |

| 23 | $15,000–$29,999 | 45 | 35 | 20 | 53 | 36 | 9 |

| 27 | $30,000–$49,999 | 41 | 38 | 21 | 48 | 40 | 10 |

| 39 | Over $50,000 | 39 | 44 | 17 | 44 | 48 | 7 |

| 18 | Over $75,000 | 36 | 48 | 16 | 41 | 51 | 7 |

| 9 | Over $100,000 | — | — | — | 38 | 54 | 6 |

| Region | |||||||

| 23 | East | 47 | 35 | 18 | 55 | 34 | 9 |

| 26 | Midwest | 42 | 37 | 21 | 48 | 41 | 10 |

| 30 | South | 41 | 43 | 16 | 46 | 46 | 7 |

| 20 | West | 43 | 34 | 23 | 48 | 40 | 8 |

| Community size | |||||||

| 10 | Population over 500,000 | 58 | 28 | 13 | 68 | 25 | 6 |

| 21 | Population 50,000 to 500,000 | 50 | 33 | 16 | 50 | 39 | 8 |

| 39 | Suburbs | 41 | 39 | 21 | 47 | 42 | 8 |

| 30 | Rural areas, towns | 39 | 40 | 20 | 45 | 44 | 10 |

Source: Voter News Service exit poll, reported in The New York Times, November 10, 1996, 28.

See also

- Chicken George

- “Giant sucking sound”

- History of the United States (1988–present)

- “Read my lips: No new taxes”

- United States Senate election, 1992

References

- "Outline of U.S. History: Chapter 15: Bridge to the 21st Century". Official web site of the U.S. Department of State. Retrieved December 10.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help)- Bulk of article text as of January 9, 2003 copied from this page, when it was located at http://usinfo.state.gov/usa/infousa/facts/history/ch13.htm#1992 and titled “An Outline of American History: Chapter 13: Toward the 21st Century”.

- An archival version of this page is available at http://web.archive.org/web/20041103020223/usinfo.state.gov/products/pubs/history/ch13.htm.

- This page is in the public domain as a government publication.

Further reading

- Abramowitz, Alan I. "It's Abortion, Stupid: Policy Voting in the 1992 Presidential Election" Journal of Politics 1995 57(1): 176-186. ISSN 0022-3816 in Jstor

- Alexander, Herbert E. (1995). Financing the 1992 Election.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Thomas M. Defrank et al. Quest for the Presidency, 1992 Texas A&M University Press. 1994.

- De la Garza, Rodolfo O. (1996). Ethnic Ironies: Latino Politics in the 1992 Elections.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Goldman, Peter L. (1994). Quest for the Presidency, 1992.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Jones, Bryan D. (1995). The New American Politics: Reflections on Political Change and the Clinton Administration.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - Steed, Robert P. (1994). The 1992 Presidential Election in the South: Current Patterns of Southern Party and Electoral Politics.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help)

External links

Navigation

- Clinton touts success, boosts Gore in nostalgic farewell to Democratic convention - Mike Ferullo, CNN, August 15, 2000

- THE 1992 CAMPAIGN: On the Trail; POLL GIVES PEROT A CLEAR LEAD - The New York Times, accessed July 5, 2006