This is an old revision of this page, as edited by ONUnicorn (talk | contribs) at 20:03, 28 December 2006 (Reverting link to You-Tube that replaced intro of article.). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 20:03, 28 December 2006 by ONUnicorn (talk | contribs) (Reverting link to You-Tube that replaced intro of article.)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)- This article discusses humour in terms of comedy and laughter. For other meanings, see Humour (disambiguation)

Humour (also spelled humor) is the ability or quality of people, objects, or situations to evoke feelings of amusement in other people. The term encompasses a form of entertainment or human communication which evokes such feelings, or which makes people laugh or feel happy.

The origin of the term derives from the humoral medicine of the ancient Greeks, which stated that a mix of fluids known as humours (Greek: χυμός, chymos, literally: juice or sap, metaphorically: flavor) controlled human health and emotion.

A sense of humour is the ability to experience humour, a quality which all people share, although the extent to which an individual will personally find something humorous depends on a host of absolute and relative variables, including geographical location, culture, maturity, level of education, and context. For example, young children (of any background) particularly favour slapstick, such as Punch and Judy puppet shows. Satire may rely more on understanding the target of the humour, and thus tends to appeal to more mature audiences.

Styles of humour

Verbal

- Black comedy

- Caustic humour

- Droll humour

- Deadpan

- Non-sequitur

- Obscenity

- Parody

- Mockery, such as the Darwin Awards

- Sarcasm

- Satire

- Self-irony / Self-deprecation

- Wit, as in many one-liner jokes

- Meta-humor

Nonverbal

- Anti-humour

- Deadpan

- Form-versus-content humour

- Slapstick

- Surreal humour or absurdity

- Practical joke: luring someone into a humourous position or situation and then laughing at their expense

Techniques for evoking humour

Humour is a branch of rhetoric, there are about 200 tropes that can be used to make jokes.

Verbal

- Figure of speech

- Inherently funny words with sounds that make them amusing in the language of delivery

- Irony, where a statement or situation implies both a superficial and a concealed meaning which are at odds with each other.

- Joke

- Adages, often in the form of paradox "laws" of nature, such as Murphy's law or Lemon Law

- Stereotyping, such as blonde jokes, lawyer jokes, racial jokes, viola jokes.

- Sick Jokes, arousing humour through grotesque, violent or exceptionally cruel scenarios

- Riddle

- Word play

Nonverbal

- Bathos

- Exaggerated or unexpected gestures and movements

- Character driven, deriving humour from the way characters act in specific situations, without punchlines. Exemplified by The Larry Sanders Show and Curb Your Enthusiasm.

- Clash of context humour, such "fish out of water"

- Comic sounds

- Deliberate ambiguity and confusion with reality, often performed by Andy Kaufman

- Unintentional humour, that is, making people laugh without intending to (as with Ed Wood's Plan 9 From Outer Space)

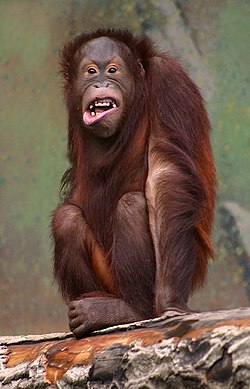

- Funny pictures: Photos or drawings/caricatures that are intentionally or unintentionally humorous.

- Sight gags

- Visual humour: Similar to the sight gag, but encompassing narrative in theatre or comics, or on film or video.

Understanding humour

Some claim that humour cannot or should not be explained. Author E. B. White once said that "Humour can be dissected as a frog can, but the thing dies in the process and the innards are discouraging to any but the pure scientific mind." However, attempts to do just that have been made.

The term "humour" as formerly applied in comedy, referred to the interpretation of the sublime and the ridiculous. In this context, humour is often a subjective experience as it depends on a special mood or perspective from its audience to be effective. Arthur Schopenhauer lamented the misuse of the term (the German loanword from English) to mean any type of comedy.

Language is an approximation of thoughts through symbolic manipulation, and the gap between the expectations inherent in those symbols and the breaking of those expectations leads to laughter (This is true for many emotions, and is not limited to laughter). Irony is explicitly this form of comedy, whereas slapstick takes more passive social norms relating to physicality and plays with them. In other words, comedy is a sign of a 'bug' in the symbolic make-up of language, as well as a self-correcting mechanism for such bugs. Once the problem in meaning has been described through a joke, people immediately begin correcting their impressions of the symbols that have been mocked. This is one explanation why jokes are often funny only when told the first time.

Another explanation is that humour frequently contains an unexpected, often sudden, shift in perspective. Nearly anything can be the object of this perspective twist. This, however, does not explain why people being humiliated and verbally abused, without it being unexpected or a shift in perspective, is considered funny - ref. The Office.

Another explanation is that the essence of humour lies in two ingredients; the relevance factor and the surprise factor. First, something familiar (or relevant) to the audience is presented. (However, the relevant situation may be so familiar to the audience that it doesn't always have to be presented, as occurs in absurd humour, for example). From there, they may think they know the natural follow-through thoughts or conclusion. The next principal ingredient is the presentation of something different from the audience's expectations, or else the natural result of interpreting the original situation in a different, less common way (see twist or surprise factor). For example:

A man speaks to his doctor after an operation. He says, "Doc, now that the surgery is done, will I be able to play the piano?" The doctor replies, "Of course!" The man says, "Good, because I couldn't before!"

The Simpsons is noted for using this technique many times to evoke humor, for example in the episode "And Maggie Makes Three" Patty and Selma are about to expose the secret of Marge's pregnancy:

Selma: (Looking at the very beginning of the phonebook) "Hi Mr. Aaronson, I'd like to inform you that Marge Simpson is pregnant."

Selma: (Looking exhausted at the very end of the phonebook) "Just thought you'd like to know, Mr. Zackowski. There! Aaronson and Zackowski are the town's biggest gossips. Within an hour, everyone will know.

Both explanations can be put under the general heading of "failed expectations". In language, or a situation with a relevance factor, or even a sublime setting, an audience has a certain expectation. If these expectations fail in a way that has some credulity, humour results. It has been postulated that the laughter/feel good element of humour is a biological function that helps one deal with the new, expanded point of view: a lawyer thinks differently than a priest or rabbi (below), a banana peel on the floor could be dangerous. This is why some link of credulity is important rather than any random line being a punchline.

For this reason, many jokes work in threes. For instance, a class of jokes exists beginning with the formulaic line "A priest, a rabbi, and a lawyer are sitting in a bar..." (or close variations on this). Typically, the priest will make a remark, the rabbi will continue in the same vein, and then the lawyer will make a third point that forms a sharp break from the established pattern, but nonetheless forms a logical (or at least stereotypical) response. Example of a variation:

A gardener, an architect, and a lawyer are discussing which of their vocations is the most ancient. The gardener comments, "My vocation goes back to the Garden of Eden, when God told Adam to tend the garden." The architect comments, "My vocation goes back to the creation, when God created the world itself from primordial chaos." They both look curiously at the lawyer, who asks, "And who do you think created the primordial chaos?"

In this vein of thought, knowing a punch line in advance, or some situation which would spoil the delivery of the punchline, can destroy the surprise factor, and in turn destroy the entertainment value or amusement the joke may have otherwise provided. Conversely, a person previously holding the same unexpected conclusions or secret perspectives as a comedian could derive amusement from hearing those same thoughts expressed and elaborated. That there is commonality, unity of thought, and an ability to openly analyse and express these (where secrecy and inhibited exploration was previously thought necessary) can be both the relevance and the surprise factors in these situations. This phenomenon explains much of the success of comedians who deal with same-gender and same-culture audiences on gender conflicts and cultural topics, respectively.

Notable studies of humour have come from the pens of Aristotle in The Poetics (Part V) and of Schopenhauer.

There also exist linguistic and psycholinguistic studies of humour, irony, parody and pretence. Prominent theoreticians in this field include Raymond Gibbs, Herbert Clark, Michael Billig, Willibald Ruch, Victor Raskin, Eliot Oring, and Salvatore Attardo. Although many writers have emphasised the positive or cathartic effects of humour some, notably Billig, have emphasised the potential of humour for cruelty and its involvement with social control and regulation.

A number of science fiction writers have explored the theory of humour. In Stranger in a Strange Land, Robert A. Heinlein proposes that humour comes from pain, and that laughter is a mechanism to keep us from crying. Isaac Asimov, on the other hand, proposes (in his first jokebook, Treasury of Humor) that the essence of humour is anticlimax: an abrupt change in point of view, in which trivial matters are suddenly elevated in importance above those that would normally be far more important.

Approaches to a general theory of humor have generally referred to analogy or some kind of analogical process of mapping structure from one domain of experience onto another. An early precursor of this approach would be Arthur Koestler, who identified humor as one of three areas of human creativity (science and art being the other two) that use structure mapping (then termed "bisociation" by Koestler) to create novel meanings. Tony Veale, who is taking a more formalized computational approach than Koestler did, has written on the role of metaphor and metonymy in humor, using inspiration from Koestler as well as from Dedre Gentner´s theory of structure-mapping, George Lakoff´s and Mark Johnson´s theory of conceptual metaphor and Mark Turner´s and Gilles Fauconnier´s theory of conceptual blending.

Humour evolution

As any form of art, humour techniques evolve through time. Perception of humour varies greatly among social demographics and indeed from person to person. Throughout history comedy has been used as a form of entertainment all over the world, whether in the courts of the kings or the villages of the far east. Both a social etiquette and a certain intelligence can be displayed through forms of wit and sarcasm.18th-century German author Georg Lichtenberg said that "the more you know humour, the more you become demanding in fineness".

Humour formula

| This article does not cite any sources. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Humour" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (October 2006) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Required components:

- some surprise/misdirection, contradiction, ambiguity or paradox.

- appealing to feelings or to emotions.

- similar to reality, but not real

Methods:

Rowan Atkinson explains in his lecture Funny Business, that an object or a person can become funny in three different ways. They are:

- By being in an unusual place

- By behaving in an unusual way

- By being the wrong size

Most sight gags fit into one or more of these categories.

Humour is also sometimes described as an ingredient in spiritual life. Some Masters have added it to their teachings in various forms. A famous figure in spiritual humour is the laughing Buddha, who would answer all questions with a laugh.

See also

|

|

References

- Koestler, Arthur (1964): "The Act of Creation".

- Veale, Tony (2003): "Metaphor and Metonymy: The Cognitive Trump-Cards of Linguistic Humor"

- Veale, Tony (2006): "The Cognitive Mechanisms of Adversarial Humor"

- Veale, Tony (2004): "Incongruity in Humour: Root Cause of Epiphenomonon?"

Literature

- Mobbs, D., Greicius, M.D., Abdel-Azim, E., Menon, V. & Reiss, A. L. Humor modulates the mesolimbic reward centers. Neuron, 40, 1041 - 1048, (2003).

- Billig, M. (2005). Laughter and ridicule: Towards a social critique of humour. London: Sage.

- Daniele Luttazzi, Introduction to his Italian translation of Woody Allen's trilogy Side Effects, Without Feathers and Getting Even (Bompiani, 2004, ISBN 88-452-3304-9 (57-65).

- Goldstein, Jeffrey H., et. al. "Humour, Laughter, and Comedy: A Bibliography of Empirical and Nonempirical Analyses in the English Language." It's a Funny Thing, Humour. Ed. Antony J. Chapman and Hugh C. Foot. Oxford and New York: Pergamon Press, 1976. 469-504.

- Holland, Norman. "Bibliography of Theories of Humor." Laughing: A Psychology of Humor. Ithaca: Cornell U P, 1982. 209-223.

- McGhee, Paul E. "Current American Psychological Research on Humor." Jahrbuche fur Internationale Germanistik 16.2 (1984): 37-57.

- Mintz, Lawrence E. Humor in America: A Research Guide to Genres and Topics. Westport, CT: Greenwood, 1988.

- Pogel, Nancy, and Paul P. Somers Jr. "Literary Humor." Humor in America: A Research Guide to Genres and Topics. Ed. Lawrence E. Mintz. London: Greenwood, 1988. 1-34.

- Nilsen, Don L. F. "Satire in American Literature." Humor in American Literature. New York: Garland, 1992. 543-48.

External links

- Dictionary of the History of ideas: Sense of the Comic

- Template:Dmoz

- Humor reference guide: a comprehensive classification and analysis

- A collection of interviews with standup comedians

- Cognitive Linguistic Approaches to Humor - theme session at the 8th International Cognitive Linguistics Conference at University of La Rioja, Spain, July 20-25, 2003 (includes speaker details and papers)