This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Johnuniq (talk | contribs) at 07:25, 30 August 2020 (Protected "Social media": Persistent disruptive editing ( (expires 07:25, 6 September 2020 (UTC)))). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 07:25, 30 August 2020 by Johnuniq (talk | contribs) (Protected "Social media": Persistent disruptive editing ( (expires 07:25, 6 September 2020 (UTC))))(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) Internet services for sharing personal information and ideas| This article may be too long to read and navigate comfortably. Consider splitting content into sub-articles, condensing it, or adding subheadings. Please discuss this issue on the article's talk page. (February 2020) |

Social media are interactive computer-mediated technologies that facilitate the creation or sharing of information, ideas, career interests and other forms of expression via virtual communities and networks. The variety of stand-alone and built-in social media services currently available introduces challenges of definition; however, there are some common features:

- Social media are interactive Web 2.0 Internet-based applications.

- User-generated content such as text posts or comments, digital photos or videos, and data generated through all online interactions, is the lifeblood of social media.

- Users create service-specific profiles for the website or app that are designed and maintained by the social media organization.

- Social media facilitate the development of online social networks by connecting a user's profile with those of other individuals or groups.

Users usually access social media services via web-based apps on desktops and laptops, or download services that offer social media functionality to their mobile devices (e.g., smartphones and tablets). As users engage with these electronic services, they create highly interactive platforms through which individuals, communities, and organizations can share, co-create, discuss, participate and modify user-generated content or self-curated content posted online. Networks formed through social media change the way groups of people interact and communicate or stand with the votes. They "introduce substantial and pervasive changes to communication between organizations, communities, and individuals". These changes are the focus of the emerging fields of technoself studies. Social media differ from paper-based media (e.g., magazines and newspapers) and traditional electronic media such as TV broadcasting, Radio broadcasting in many ways, including quality, reach, frequency, interactivity, usability, immediacy, and performance. Social media outlets operate in a dialogic transmission system (many sources to many receivers). This is in contrast to traditional media which operates under a mono-logic transmission model (one source to many receivers), such as a newspaper which is delivered to many subscribers, or a radio station which broadcasts the same programs to an entire city. Some of the most popular social media websites, with over 100 million registered users, include Facebook (and its associated Facebook Messenger), TikTok, WeChat, Instagram, QZone, Weibo, Twitter, Tumblr, Baidu Tieba and LinkedIn. Other popular platforms that are sometimes referred to as social media services (differing on interpretation) include YouTube, QQ, Quora, Telegram, WhatsApp, LINE, Snapchat, Pinterest, Viber, Reddit, Discord, VK, and more.

Observers have noted a wide range of positive and negative impacts of social media use. Social media can help to improve an individual's sense of connectedness with real or online communities and can be an effective communication (or marketing) tool for corporations, entrepreneurs, non-profit organizations, advocacy groups, political parties, and governments.

History

See also: Information Age Front panel of the 1969-era ARPANET Interface Message Processor.

Front panel of the 1969-era ARPANET Interface Message Processor. IMP log for the first message sent over the Internet, using ARPANET.

IMP log for the first message sent over the Internet, using ARPANET.

Social media may have roots in the 1840s introduction of the telegraph, which connected the United States. The PLATO system launched in 1960, after being developed at the University of Illinois and subsequently commercially marketed by Control Data Corporation. It offered early forms of social media features with 1973-era innovations such as Notes, PLATO's message-forum application; TERM-talk, its instant-messaging feature; Talkomatic, perhaps the first online chat room; News Report, a crowd-sourced online newspaper and blog; and Access Lists, enabling the owner of a note file or other application to limit access to a certain set of users, for example, only friends, classmates, or co-workers.

ARPANET, which first came online in 1967, had by the late 1970s developed a rich cultural exchange of non-government/business ideas and communication, as evidenced by the network etiquette (or "netiquette") described in a 1982 handbook on computing at MIT's Artificial Intelligence Laboratory. ARPANET evolved into the Internet following the publication of the first Transmission Control Protocol (TCP) specification, RFC 675 (Specification of Internet Transmission Control Program), written by Vint Cerf, Yogen Dalal and Carl Sunshine in 1974. This became the foundation of Usenet, conceived by Tom Truscott and Jim Ellis in 1979 at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and Duke University, and established in 1980.

A precursor of the electronic bulletin board system (BBS), known as Community Memory, had already appeared by 1973. True electronic bulletin board systems arrived with the Computer Bulletin Board System in Chicago, which first came online on February 16, 1978. Before long, most major cities had more than one BBS running on TRS-80, Apple II, Atari, IBM PC, Commodore 64, Sinclair, and similar personal computers. The IBM PC was introduced in 1981, and subsequent models of both Mac computers and PCs were used throughout the 1980s. Multiple modems, followed by specialized telecommunication hardware, allowed many users to be online simultaneously. Compuserve, Prodigy and AOL were three of the largest BBS companies and were the first to migrate to the Internet in the 1990s. Between the mid-1980s and the mid-1990s, BBSes numbered in the tens of thousands in North America alone. Message forums (a specific structure of social media) arose with the BBS phenomenon throughout the 1980s and early 1990s. When the World Wide Web (WWW, or "the web") was added to the Internet in the mid-1990s, message forums migrated to the web, becoming Internet forums, primarily due to cheaper per-person access as well as the ability to handle far more people simultaneously than telco modem banks.

Digital imaging and semiconductor image sensor technology facilitated the development and rise of social media. Advances in metal-oxide-semiconductor (MOS) semiconductor device fabrication, reaching smaller micron and then sub-micron levels during the 1980s–1990s, led to the development of the NMOS (n-type MOS) active-pixel sensor (APS) at Olympus in 1985, and then the complementary MOS (CMOS) active-pixel sensor (CMOS sensor) at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in 1993. CMOS sensors enabled the mass proliferation of digital cameras and camera phones, which bolstered the rise of social media.

An important feature of social media is digital media data compression, due to the impractically high memory and bandwidth requirements of uncompressed media. The most important compression algorithm is the discrete cosine transform (DCT), a lossy compression technique that was first proposed by Nasir Ahmed in 1972. DCT-based compression standards include the H.26x and MPEG video coding standards introduced from 1988 onwards, and the JPEG image compression standard introduced in 1992. JPEG was largely responsible for the proliferation of digital images and digital photos which lie at the heart of social media, and the MPEG standards did the same for digital video content on social media. The JPEG image format is used more than a billion times on social networks every day, as of 2014.

GeoCities was one of the World Wide Web's earliest social networking websites, appearing in November 1994, followed by Classmates in December 1995 and SixDegrees in May 1997. According to CBS news, SixDegrees is "widely considered to be the very first social networking site", as it included "profiles, friends lists and school affiliations" that could be used by registered users. Open Diary was launched in October 1998; LiveJournal in April 1999; Ryze in October 2001; Friendster in March 2003; the corporate and job-oriented site LinkedIn in May 2003; hi5 in June 2003; MySpace in August 2003; Orkut in January 2004; Facebook in February 2004; YouTube in February 2005; Yahoo! 360° in March 2005; Bebo in July 2005; the text-based service Twitter, in which posts, called "tweets", were limited to 140 characters, in July 2006; Tumblr in February 2007; Instagram in July 2010; and Google+ in July 2011.

Definition and classification

The variety of evolving stand-alone and built-in social media services makes it challenging to define them. However, marketing and social media experts broadly agree that social media includes the following 13 types of social media:

- blogs,

- business networks,

- collaborative projects,

- enterprise social networks,

- forums,

- microblogs,

- photo sharing,

- products/services review,

- social bookmarking,

- social gaming,

- social networks,

- video sharing, and

- virtual worlds.

The idea that social media are defined simply by their ability to bring people together has been seen as too broad, as this would suggest that fundamentally different technologies like the telegraph and telephone are also social media. The terminology is unclear, with some early researchers referring to social media as social networks or social networking services in the mid 2000s. A more recent paper from 2015 reviewed the prominent literature in the area and identified four common features unique to then-current social media services:

- Social media are Web 2.0 Internet-based applications.

- User-generated content (UGC) is the lifeblood of the social media organism.

- Users create service-specific profiles for the site or app that are designed and maintained by the social media organization.

- Social media facilitate the development of online social networks by connecting a user's profile with those of other individuals or groups.

In 2019, Merriam-Webster defined "social media" as "forms of electronic communication (such as websites for social networking and microblogging) through which users create online communities to share information, ideas, personal messages, and other content (such as videos)"

The development of social media started off with simple platforms such as sixdegrees.com. Unlike instant messaging clients, such as ICQ and AOL's AIM, or chat clients like IRC, iChat or Chat Television, sixdegrees.com was the first online business that was created for real people, using their real names. The first social networks were short-lived, however, because their users lost interest. The Social Network Revolution has led to the rise of networking sites. Research shows that the audience spends 22% of their time on social networks, thus proving how popular social media platforms have become. This increase is because of the widespread daily use of smartphones. Social media are used to document memories, learn about and explore things, advertise oneself and form friendships as well as the growth of ideas from the creation of blogs, podcasts, videos, and gaming sites. Networked individuals create, edit, and manage content in collaboration with other networked individuals. This way they contribute to expanding knowledge. Wikis are examples of collaborative content creation.

Mobile social media

Mobile social media refer to the use of social media on mobile devices such as smartphones and tablet computers. Mobile social media are a useful application of mobile marketing because the creation, exchange, and circulation of user-generated content can assist companies with marketing research, communication, and relationship development. Mobile social media differ from others because they incorporate the current location of the user (location-sensitivity) or the time delay between sending and receiving messages (time-sensitivity). According to Andreas Kaplan, mobile social media applications can be differentiated among four types:

- Space-timers (location and time sensitive): Exchange of messages with relevance mostly for one specific location at one specific point in time (e.g. Facebook Places WhatsApp; Foursquare)

- Space-locators (only location sensitive): Exchange of messages, with relevance for one specific location, which is tagged to a certain place and read later by others (e.g. Yelp; Qype, Tumblr, Fishbrain)

- Quick-timers (only time sensitive): Transfer of traditional social media mobile apps to increase immediacy (e.g. posting Twitter messages or Facebook status updates)

- Slow-timers (neither location nor time sensitive): Transfer of traditional social media applications to mobile devices (e.g. watching a YouTube video or reading/editing a Misplaced Pages article)

Elements and function

Viral content

Some social media sites have potential for content posted there to spread virally over social networks. The term is an analogy to the concept of viral infections, which can spread rapidly from person to person. In a social media context, content or websites that are "viral" (or which "go viral") are those with a greater likelihood that users will reshare content posted (by another user) to their social network, leading to further sharing. In some cases, posts containing popular content or fast-breaking news have been rapidly shared and reshared by a huge number of users. Many social media sites provide specific functionality to help users reshare content, such as Twitter's retweet button, Pinterest's pin function, Facebook's share option or Tumblr's reblog function. Businesses have a particular interest in viral marketing tactics because a viral campaign can achieve widespread advertising coverage (particularly if the viral reposting itself makes the news) for a fraction of the cost of a traditional marketing campaign, which typically uses printed materials, like newspapers, magazines, mailings, and billboards, and television and radio commercials. Nonprofit organizations and activists may have similar interests in posting content on social media sites with the aim of it going viral. A popular component and feature of Twitter is retweeting. Twitter allows other people to keep up with important events, stay connected with their peers, and can contribute in various ways throughout social media. When certain posts become popular, they start to get retweeted over and over again, becoming viral. Hashtags can be used in tweets, and can also be used to take count of how many people have used that hashtag.

Bots

Social media can enable companies to get in the form of greater market share and increased audiences. Internet bots have been developed which facilitate social media marketing. Bots are automated programs that run over the Internet. Chatbots and social bots are programmed to mimic natural human interactions such as liking, commenting, following, and unfollowing on social media platforms. A new industry of bot providers has been created. Social bots and chatbots have created an analytical crisis in the marketing industry as they make it difficult to differentiate between human interactions and automated bot interactions. Some bots are negatively affecting their marketing data causing a "digital cannibalism" in social media marketing. Additionally, some bots violate the terms of use on many social mediums such as Instagram, which can result in profiles being taken down and banned.

"Cyborgs", a combination of a human and a bot, are used to spread fake news or create a marketing "buzz". Cyborgs can be bot-assisted humans or human-assisted bots. An example is a human who registers an account for which they set automated programs to post, for instance, tweets, during their absence. From time to time, the human participates to tweet and interact with friends. Cyborgs make it easier to spread fake news, as it blends automated activity with human input. When the automated accounts are publicly identified, the human part of the cyborg is able to take over and could protest that the account has been used manually all along. Such accounts try to pose as real people; in particular, the number of their friends or followers should be resembling that of a real person.

Patents of social media technology

Main article: Software patent

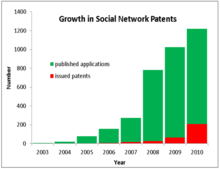

There has been rapid growth in the number of U.S. patent applications that cover new technologies related to social media, and the number of them that are published has been growing rapidly over the past five years. There are now over 2000 published patent applications. As many as 7000 applications may be currently on file including those that haven't been published yet. Only slightly over 100 of these applications have issued as patents, however, largely due to the multi-year backlog in examination of business method patents, patents which outline and claim new methods of doing business.

Statistics on usage and membership

According to Statista, in 2020, it is estimated that there are around 3.6 billion people using social media around the globe, up from 3.4 billion in 2019. The number is expected to increase to 4.41 billion in 2025.

Most popular social networks

The following list of the leading social networks shows the number of active users as of April 2020 (figures for Baidu Tieba, LinkedIn, Viber and Discord are from October 2019).

| # | Network Name | Number of Users

(in millions) |

Country of Origin |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2,498 | ||

| 2 | YouTube | 2,000 | |

| 3 | 2,000 | ||

| 4 | Facebook Messenger | 1,300 | |

| 5 | 1,165 | ||

| 6 | 1,000 | ||

| 7 | TikTok | 800 | |

| 8 | 731 | ||

| 9 | Qzone | 517 | |

| 10 | Sina Weibo | 516 | |

| 11 | 430 | ||

| 12 | Kuaishou | 400 | |

| 13 | Snapchat | 398 | |

| 14 | 386 | ||

| 15 | 366 | ||

| 16 | Baidu Tieba | 320 | |

| 17 | 310 | ||

| 18 | Viber | 260 | |

| 19 | Discord | 250 |

Usage

According to a survey conducted by Pew Research in 2018, Facebook and YouTube dominate the social media landscape, as notable majorities of U.S. adults use each of these sites. At the same time, younger Americans (especially those ages 18 to 24) stand out for embracing a variety of platforms and using them frequently. Some 78% of 18 - 24-year-old youngsters use Snapchat, and a sizeable majority of these users (71%) visit the platform multiple times per day. Similarly, 71% of Americans in this age group now use Instagram and close to half (45%) are Twitter users. However, Facebook remains the primary platform for most Americans. Roughly two-thirds of U.S. adults (68%) now report that they are Facebook users, and roughly three-quarters of those users access Facebook on a daily basis. With the exception of those 65 and older, a majority of Americans across a wide range of demographic groups now use Facebook. After this rapid growth, the number of new U.S. Facebook accounts created has plateaued, with not much observable growth in the 2016-18 period.

Use by organizations

Use by governments

Governments may use social media to (for example):

- interact with citizens

- foster citizen participation

- further open government

- analyze/monitor public opinion and activities

Use by businesses

Main article: Social media use by businessesThe high distribution of social media in the private environment drives companies to deal with the application possibilities of social media on

- customer-organizational level

- and on intra-organizational level.

Marketplace actors can use social-media tools for marketing research, communication, sales promotions/discounts, informal employee-learning/organizational development, relationship development/loyalty programs, and e-Commerce. Often social media can become a good source of information and/or explanation of industry trends for a business to embrace change. Trends in social-media technology and usage change rapidly, making it crucial for businesses to have a set of guidelines that can apply to many social media platforms.

Companies are increasingly using social-media monitoring tools to monitor, track, and analyze online conversations on the Web about their brand or products or about related topics of interest. This can prove useful in public relations management and advertising-campaign tracking, allowing analysts to measure return on investment for their social media ad spending, competitor-auditing, and for public engagement. Tools range from free, basic applications to subscription-based, more in-depth tools.

Financial industries utilize the power of social media as a tool for analyzing sentiment of financial markets. These range from the marketing of financial products, gaining insights into market sentiment, future market predictions, and as a tool to identify insider trading.

Social media becomes effective through a process called "building social authority". One of the foundation concepts in social media has become that one cannot completely control one's message through social media but rather one can simply begin to participate in the "conversation" expecting that one can achieve a significant influence in that conversation.

Social media mining

Main article: Social media miningSocial media "mining" is a type of data mining, a technique of analyzing data to detect patterns. Social media mining is a process of representing, analyzing, and extracting actionable patterns from data collected from people's activities on social media. Google mines data in many ways including using an algorithm in Gmail to analyze information in emails. This use of the information will then affect the type of advertisements shown to the user when they use Gmail. Facebook has partnered with many data mining companies such as Datalogix and BlueKai to use customer information for targeted advertising. Ethical questions of the extent to which a company should be able to utilize a user's information have been called "big data". Users tend to click through Terms of Use agreements when signing up on social media platforms, and they do not know how their information will be used by companies. This leads to questions of privacy and surveillance when user data is recorded. Some social media outlets have added capture time and Geotagging that helps provide information about the context of the data as well as making their data more accurate.

In politics

See also: Social impact of YouTube, Use of social media in the Wisconsin protests, and Social media and political communication in the United States Main article: Social media use in politics| This article reads like a press release or a news article and may be largely based on routine coverage. Please help improve this article and add independent sources. (June 2016) |

Social media has a range of uses in political processes and activities. Social media have been championed as allowing anyone with an Internet connection to become a content creator and empowering their users. The role of social media in democratizing media participation, which proponents herald as ushering in a new era of participatory democracy, with all users able to contribute news and comments, may fall short of the ideals, given that many often follow like-minded individuals, as noted by Philip Pond and Jeff Lewis. Online media audience members are largely passive consumers, while content creation is dominated by a small number of users who post comments and write new content.

Younger generations are becoming more involved in politics due to the increase of political news posted on social media. Political campaigns are targeting Millennials online via social media posts in hope that they will increase their political engagement. Social media was influential in the widespread attention given to the revolutionary outbreaks in the Middle East and North Africa during 2011. During the Tunisian revolution in 2011, people used Facebook to organize meetings and protests. However, there is debate about the extent to which social media facilitated this kind of political change.

Social Media footprints of candidates have grown during the last decade and the 2016 United States Presidential election provides a good example. Dounoucos et al. noted that Twitter use by the candidates was unprecedented during that election cycle. Most candidates in the United States have a Twitter account. The public has also increased their reliance on social media sites for political information. In the European Union, social media has amplified political messages.

One challenge is that militant groups have begun to see social media as a major organizing and recruiting tool. The Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant, also known as ISIL, ISIS, and Daesh, has used social media to promote its cause. In 2014, #AllEyesonISIS went viral on Arabic Twitter. ISIS produces an online magazine named the Islamic State Report to recruit more fighters. Social media platforms have been weaponized by state-sponsored cyber groups to attack governments in the United States, European Union, and Middle East. Although phishing attacks via email are the most commonly used tactic to breach government networks, phishing attacks on social media rose 500% in 2016.

Use in hiring

Main article: Social media use in hiring

Some employers examine job applicants' social media profiles as part of the hiring assessment. This issue raises many ethical questions that some consider an employer's right and others consider discrimination. Many Western European countries have already implemented laws that restrict the regulation of social media in the workplace. States including Arkansas, California, Colorado, Illinois, Maryland, Michigan, Nevada, New Jersey, New Mexico, Utah, Washington, and Wisconsin have passed legislation that protects potential employees and current employees from employers that demand that they provide their usernames and/or passwords for any social media accounts. Use of social media by young people has caused significant problems for some applicants who are active on social media when they try to enter the job market. A survey of 17,000 young people in six countries in 2013 found that 1 in 10 people aged 16 to 34 have been rejected for a job because of online comments they made on social media websites.

Use in school admissions

It is not only an issue in the workplace but an issue in post-secondary school admissions as well. There have been situations where students have been forced to give up their social media passwords to school administrators. There are inadequate laws to protect a student's social media privacy, and organizations such as the ACLU are pushing for more privacy protection, as it is an invasion. They urge students who are pressured to give up their account information to tell the administrators to contact a parent or lawyer before they take the matter any further. Although they are students, they still have the right to keep their password-protected information private.

Before social media, admissions officials in the United States used SAT and other standardized test scores, extra-curricular activities, letters of recommendation, and high school report cards to determine whether to accept or deny an applicant. In the 2010s, while colleges and universities still use these traditional methods to evaluate applicants, these institutions are increasingly accessing applicants' social media profiles to learn about their character and activities. According to Kaplan, Inc, a corporation that provides higher education preparation, in 2012 27% of admissions officers used Google to learn more about an applicant, with 26% checking Facebook. Students whose social media pages include offensive jokes or photos, racist or homophobic comments, photos depicting the applicant engaging in illegal drug use or drunkenness, and so on, may be screened out from admission processes.

Use in law enforcement and investigations

Social media has been used extensively in civil and criminal investigations. It has also been used to assist in searches for missing persons. Police departments often make use of official social media accounts to engage with the public, publicize police activity, and burnish law enforcement's image; conversely, video footage of citizen-documented police brutality and other misconduct has sometimes been posted to social media.

In the United States U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement identifies and track individuals via social media, and also has apprehended some people via social media based sting operations. U.S. Customs and Border Protection (also known as CPB) and the United States Department of Homeland Security use social media data as influencing factors during the visa process, and continue to monitor individuals after they have entered the country. CPB officers have also been documented performing searches of electronics and social media behavior at the border, searching both citizens and non-citizens without first obtaining a warrant.

Use in court cases

Social media comments and images are being used in a range of court cases including employment law, child custody/child support and insurance disability claims. After an Apple employee criticized his employer on Facebook, he was fired. When the former employee sued Apple for unfair dismissal, the court, after seeing the man's Facebook posts, found in favor of Apple, as the man's social media comments breached Apple's policies. After a heterosexual couple broke up, the man posted "violent rap lyrics from a song that talked about fantasies of killing the rapper's ex-wife" and made threats against him. The court found him guilty and he was sentenced to jail. In a disability claims case, a woman who fell at work claimed that she was permanently injured; the employer used her social media posts of her travels and activities to counter her claims.

Courts do not always admit social media evidence, in part because screenshots can be faked or tampered with. Judges are taking emojis into account to assess statements made on social media; in one Michigan case where a person alleged that another person had defamed them in an online comment, the judge disagreed, noting that there was an emoji after the comment which indicated that it was a joke. In a 2014 case in Ontario against a police officer regarding alleged assault of a protester during the G20 summit, the court rejected the Crown's application to use a digital photo of the protest that was anonymously posted online, because there was no metadata proving when the photo was taken and it could have been digitally altered.

Social media marketing

Social media marketing is the use of social media platforms and websites to promote a product or service. Although the terms e-marketing and digital marketing are still dominant in academia, social media marketing is becoming more popular for both practitioners and researchers. Social media marketing has increased due to the growing active user rates on social media sites. For example, Facebook currently has 2.2 billion users, Twitter has 330 million active users and Instagram has 800 million users. One of the main uses is to interact with audiences to create awareness of their brand or service, with the main idea of creating a two-way communication system where the audience and/or customers can interact back; providing feedback as just one example. Social media can be used to advertise; placing an advert on Facebook's Newsfeed, for example, can allow a vast number of people to see it or targeting specific audiences from their usage to encourage awareness of the product or brand. Users of social media are then able to like, share and comment on the advert, becoming message senders as they can keep passing the advert's message on to their friends and onwards. The use of new media put consumers on the position of spreading opinions, sharing experience, and has shift power from organization to consumers for it allows transparency and different opinions to be heard. media marketing has to keep up with all the different platforms. They also have to keep up with the ongoing trends that are set by big influencers and draw many peoples attention. The type of audience a business is going for will determine the social media site they use.

Social media personalities have been employed by marketers to promote products online. Research shows that digital endorsements seem to be successfully targeting social media users, especially younger consumers who have grown up in the digital age. In 2013, the United Kingdom Advertising Standards Authority (ASA) began to advise celebrities and sports stars to make it clear if they had been paid to tweet about a product or service by using the hashtag #spon or #ad within tweets containing endorsements. The practice of harnessing social media personalities to market or promote a product or service to their following is commonly referred to as Influencer Marketing. The Cambridge Dictionary defines an "influencer" as any person (personality, blogger, journalist, celebrity) who has the ability to affect the opinions, behaviors, or purchases of others through the use of social media.

Companies such as fast food franchise Wendy's have used humor to advertise their products by poking fun at competitors such as McDonald's and Burger King. Other companies such as Juul have used hashtags to promote themselves and their products.

On social media, consumers are exposed to the purchasing practices of peers through messages from a peer's account, which may be peer-written. Such messages may be part of an interactive marketing strategy involving modeling, reinforcement, and social interaction mechanisms. A 2011 study focusing on peer communication through social media described how communication between peers through social media can affect purchase intentions: a direct impact through conformity, and an indirect impact by stressing product engagement. The study indicated that social media communication between peers about a product had a positive relationship with product engagement.

Use in science

Signals from social media are used to assess academic publications, as well as for different scientific approaches. One of the studies examined how millions of users interact with socially shared news and show that individuals’ choices played a stronger role in limiting exposure to cross-cutting content. Another study found that most of the health science students acquiring academic materials from others through social media. Massive amounts of data from social platforms allows scientists and machine learning researchers to extract insights and build product features. Using social media can help to shape patterns of deception in resumes.

Use by individuals

As a news source

Main article: Social media as a news sourceIn the United States, 81% of users look online for news of the weather, first and foremost, with the percentage seeking national news at 73%, 52% for sports news, and 41% for entertainment or celebrity news. According to CNN, in 2010 75% of people got their news forwarded through e-mail or social media posts, whereas 37% of people shared a news item via Facebook or Twitter. Facebook and Twitter make news a more participatory experience than before as people share news articles and comment on other people's posts. Rainie and Wellman have argued that media making now has become a participation work, which changes communication systems. However, 27% of respondents worry about the accuracy of a story on a blog. From a 2019 poll, Pew Research Center found that Americans are wary about the ways that social media sites share news and certain content. This wariness of accuracy is on the rise as social media sites are increasingly exploited by aggregated new sources which stitch together multiple feeds to develop plausible correlations. Hemsley, Jacobson et al. refer to this phenomenon as "pseudoknowledge" which develop false narratives and fake news that are supported through general analysis and ideology rather than facts. Social media as a news source is further questioned as spikes in evidence surround major news events such as was captured in the United States 2016 presidential election.

Effects on individual and collective memory

News media and television journalism have been a key feature in the shaping of American collective memory for much of the twentieth century. Indeed, since the United States' colonial era, news media has influenced collective memory and discourse about national development and trauma. In many ways, mainstream journalists have maintained an authoritative voice as the storytellers of the American past. Their documentary style narratives, detailed exposes, and their positions in the present make them prime sources for public memory. Specifically, news media journalists have shaped collective memory on nearly every major national event – from the deaths of social and political figures to the progression of political hopefuls. Journalists provide elaborate descriptions of commemorative events in U.S. history and contemporary popular cultural sensations. Many Americans learn the significance of historical events and political issues through news media, as they are presented on popular news stations. However, journalistic influence is growing less important, whereas social networking sites such as Facebook, YouTube and Twitter, provide a constant supply of alternative news sources for users.

As social networking becomes more popular among older and younger generations, sites such as Facebook and YouTube, gradually undermine the traditionally authoritative voices of news media. For example, American citizens contest media coverage of various social and political events as they see fit, inserting their voices into the narratives about America's past and present and shaping their own collective memories. An example of this is the public explosion of the Trayvon Martin shooting in Sanford, Florida. News media coverage of the incident was minimal until social media users made the story recognizable through their constant discussion of the case. Approximately one month after the fatal shooting of Trayvon Martin, its online coverage by everyday Americans garnered national attention from mainstream media journalists, in turn exemplifying media activism. In some ways, the spread of this tragic event through alternative news sources parallels that of Emmett Till – whose murder by lynching in 1955 became a national story after it was circulated in African-American and Communist newspapers.

Interpersonal relationships

Social media is used to fulfill perceived social needs, but not all needs can be fulfilled by social media. For example, lonely individuals are more likely to use the Internet for emotional support than those who are not lonely. Sherry Turkle explores these issues in her book Alone Together as she discusses how people confuse social media usage with authentic communication. She posits that people tend to act differently online and are less afraid to hurt each other's feelings. Additionally, studies on who interacts on the internet have shown that extraversion and openness have a positive relationship with social media, while emotional stability has a negative sloping relationship with social media.

Some online behaviors can cause stress and anxiety, due to the permanence of online posts, the fear of being hacked, or of universities and employers exploring social media pages. Turkle also speculates that people are beginning to prefer texting to face-to-face communication, which can contribute to feelings of loneliness. Some researchers have also found that exchanges that involved direct communication and reciprocation of messages correlated with less feelings of loneliness. However, passively using social media without sending or receiving messages does not make people feel less lonely unless they were lonely to begin with.

Checking updates on friends' activities on social media is associated with the "fear of missing out" (FOMO), the "pervasive apprehension that others might be having rewarding experiences from which one is absent". FOMO is a social anxiety characterized by "a desire to stay continually connected with what others are doing". It has negative influences on people's psychological health and well-being because it could contribute to negative mood and depressed feelings.

Concerns have been raised about online "stalking" or "creeping" of people on social media, which means looking at the person's "timeline, status updates, tweets, and online bios" to find information about them and their activities. While social media creeping is common, it is considered to be poor form to admit to a new acquaintance or new date that you have looked through his or her social media posts, particularly older posts, as this will indicate that you were going through their old history. A sub-category of creeping is creeping ex-partners' social media posts after a breakup to investigate if there is a new partner or new dating; this can lead to preoccupation with the ex, rumination and negative feelings, all of which postpone recovery and increase feelings of loss. Catfishing has become more prevalent since the advent of social media. Relationships formed with catfish can lead to actions such as supporting them with money and catfish will typically make excuses as to why they cannot meet up or be viewed on camera.

According to research from UCLA, teenage brains' reward circuits were more active when teenager's photos were liked by more peers. This has both positive and negative features. Teenagers and young adults befriend people online whom they do not know well. This opens the possibility of a child being influenced by people who engage in risk-taking behavior. When children have several hundred online connections there is no way for parents to know who they are.

Self-presentation

The more time people spend on Facebook, the less satisfied they feel about their life. Self-presentational theory explains that people will consciously manage their self-image or identity related information in social contexts. When people are not accepted or are criticized online they feel emotional pain. This may lead to some form of online retaliation such as online bullying. Trudy Hui Hui Chua and Leanne Chang's article, "Follow Me and Like My Beautiful Selfies: Singapore Teenage Girls' Engagement in Self-Presentation and Peer Comparison on Social Media" states that teenage girls manipulate their self-presentation on social media to achieve a sense of beauty that is projected by their peers. These authors also discovered that teenage girls compare themselves to their peers on social media and present themselves in certain ways in effort to earn regard and acceptance, which can actually lead to problems with self-confidence and self-satisfaction.

Users also tend to segment their audiences based on the image they want to present, pseudonymity and use of multiple accounts across the same platform remain popular ways to negotiate platform expectations and segment audiences.

Health improvement and behavior reinforcement

Social media can also function as a supportive system for adolescents' health, because by using social media, adolescents are able to mobilize around health issues that they themselves deem relevant. For example, in a clinical study among adolescent patients undergoing treatment for obesity, the participants' expressed that through social media, they could find personalized weight-loss content as well as social support among other adolescents with obesity The same authors also found that as with other types of online information, the adolescents need to possess necessary skills to evaluate and identify reliable health information, competencies commonly known as health literacy.

Other social media, such as pro-anorexia sites, have been found in studies to cause significant risk of harm by reinforcing negative health-related behaviors through social networking, especially in adolescents.

Social impacts

Disparity

The digital divide is a measure of disparity in the level of access to technology between households, socioeconomic levels or other demographic categories. People who are homeless, living in poverty, elderly people and those living in rural or remote communities may have little or no access to computers and the Internet; in contrast, middle class and upper-class people in urban areas have very high rates of computer and Internet access. Other models argue that within a modern information society, some individuals produce Internet content while others only consume it, which could be a result of disparities in the education system where only some teachers integrate technology into the classroom and teach critical thinking. While social media has differences among age groups, a 2010 study in the United States found no racial divide. Some zero-rating programs offer subsidized data access to certain websites on low-cost plans. Critics say that this is an anti-competitive program that undermines net neutrality and creates a "walled garden" for platforms like Facebook Zero. A 2015 study found that 65% of Nigerians, 61% of Indonesians, and 58% of Indians agree with the statement that "Facebook is the Internet" compared with only 5% in the US.

Eric Ehrmann contends that social media in the form of public diplomacy create a patina of inclusiveness that covers traditional economic interests that are structured to ensure that wealth is pumped up to the top of the economic pyramid, perpetuating the digital divide and post Marxian class conflict. He also voices concern over the trend that finds social utilities operating in a quasi-libertarian global environment of oligopoly that requires users in economically challenged nations to spend high percentages of annual income to pay for devices and services to participate in the social media lifestyle. Neil Postman also contends that social media will increase an information disparity between "winners" – who are able to use the social media actively – and "losers" – who are not familiar with modern technologies or who do not have access to them. People with high social media skills may have better access to information about job opportunities, potential new friends, and social activities in their area, which may enable them to improve their standard of living and their quality of life.

Political polarization

According to the Pew Research Center, a majority of Americans at least occasionally receive news from social media. Because of algorithms on social media which filter and display news content which are likely to match their users’ political preferences, a potential impact of receiving news from social media includes an increase in political polarization due to selective exposure. Political polarization refers to when an individual's stance on a topic is more likely to be strictly defined by their identification with a specific political party or ideology than on other factors. Selective exposure occurs when an individual favors information which supports their beliefs and avoids information which conflicts with their beliefs. A study by Hayat and Samuel-Azran conducted during the 2016 U.S. presidential election observed an "echo chamber" effect of selective exposure among 27,811 Twitter users following the content of cable news shows. The Twitter users observed in the study were found to have little interaction with users and content whose beliefs were different from their own, possibly heightening polarization effects.

Efforts to combat selective exposure in social media may also cause an increase in political polarization. A study examining Twitter activity conducted by Bail et al. paid Democrat and Republican participants to follow Twitter handles whose content was different from their political beliefs (Republicans received liberal content and Democrats received conservative content) over a six-week period. At the end of the study, both Democrat and Republican participants were found to have increased political polarization in favor of their own parties, though only Republican participants had an increase that was statistically significant.

Though research has shown evidence that social media plays a role in increasing political polarization, it has also shown evidence that social media use leads to a persuasion of political beliefs. An online survey consisting of 1,024 U.S. participants was conducted by Diehl, Weeks, and Gil de Zuñiga, which found that individuals who use social media were more likely to have their political beliefs persuaded than those who did not. In particular, those using social media as a means to receive their news were the most likely to have their political beliefs changed. Diehl et al. found that the persuasion reported by participants was influenced by the exposure to diverse viewpoints they experienced, both in the content they saw as well as the political discussions they participated in. Similarly, a study by Hardy and colleagues conducted with 189 students from a Midwestern state university examined the persuasive effect of watching a political comedy video on Facebook. Hardy et al. found that after watching a Facebook video of the comedian/political commentator John Oliver performing a segment on his show, participants were likely to be persuaded to change their viewpoint on the topic they watched (either payday lending or the Ferguson protests) to one that was closer to the opinion expressed by Oliver. Furthermore, the persuasion experienced by the participants was found to be reduced if they viewed comments by Facebook users which contradicted the arguments made by Oliver.

Research has also shown that social media use may not have an effect on polarization at all. A U.S. national survey of 1,032 participants conducted by Lee et al. found that participants who used social media were more likely to be exposed to a diverse number of people and amount of opinion than those who did not, although using social media was not correlated with a change in political polarization for these participants.

In a study examining the potential polarizing effects of social media on the political views of its users, Mihailidis and Viotty suggest that a new way of engaging with social media must occur to avoid polarization. The authors note that media literacies (described as methods which give people skills to critique and create media) are important to using social media in a responsible and productive way, and state that these literacies must be changed further in order to have the most effectiveness. In order to decrease polarization and encourage cooperation among social media users, Mihailidis and Viotty suggest that media literacies must focus on teaching individuals how to connect with other people in a caring way, embrace differences, and understand the ways in which social media has a realistic impact on the political, social, and cultural issues of the society they are a part of.

Stereotyping

Recent research has demonstrated that social media, and media in general, have the power to increase the scope of stereotypes not only in children but people all ages. Three researchers at Blanquerna University, Spain, examined how adolescents interact with social media and specifically Facebook. They suggest that interactions on the website encourage representing oneself in the traditional gender constructs, which helps maintain gender stereotypes. The authors noted that girls generally show more emotion in their posts and more frequently change their profile pictures, which according to some psychologists can lead to self-objectification. On the other hand, the researchers found that boys prefer to portray themselves as strong, independent, and powerful. For example, men often post pictures of objects and not themselves, and rarely change their profile pictures; using the pages more for entertainment and pragmatic reasons. In contrast girls generally post more images that include themselves, friends and things they have emotional ties to, which the researchers attributed that to the higher emotional intelligence of girls at a younger age. The authors sampled over 632 girls and boys from the ages of 12–16 from Spain in an effort to confirm their beliefs. The researchers concluded that masculinity is more commonly associated with a positive psychological well-being, while femininity displays less psychological well-being. Furthermore, the researchers discovered that people tend not to completely conform to either stereotype, and encompass desirable parts of both. Users of Facebook generally use their profile to reflect that they are a "normal" person. Social media was found to uphold gender stereotypes both feminine and masculine. The researchers also noted that the traditional stereotypes are often upheld by boys more so than girls. The authors described how neither stereotype was entirely positive, but most people viewed masculine values as more positive.

Physical and mental health

There are several negative effects to social media which receive criticism, for example regarding privacy issues, information overload and Internet fraud. Social media can also have negative social effects on users. Angry or emotional conversations can lead to real-world interactions outside of the Internet, which can get users into dangerous situations. Some users have experienced threats of violence online and have feared these threats manifesting themselves offline. At the same time, concerns have been raised about possible links between heavy social media use and depression, and even the issues of cyberbullying, online harassment and "trolling". According to cyber bullying statistics from the i-Safe Foundation, over half of adolescents and teens have been bullied online, and about the same number have engaged in cyber bullying. Both the bully and the victim are negatively affected, and the intensity, duration, and frequency of bullying are the three aspects that increase the negative effects on both of them. Studies also show that social media have negative effects on peoples' self-esteem and self-worth. The authors of "Who Compares and Despairs? The Effect of Social Comparison Orientation on Social Media Use and its Outcomes" found that people with a higher social comparison orientation appear to use social media more heavily than people with low social comparison orientation. This finding was consistent with other studies that found people with high social comparison orientation make more social comparisons once on social media.

People compare their own lives to the lives of their friends through their friends' posts. People are motivated to portray themselves in a way that is appropriate to the situation and serves their best interest. Often the things posted online are the positive aspects of people's lives, making other people question why their own lives are not as exciting or fulfilling. This can lead to depression and other self-esteem issues as well as decrease their satisfaction of life as they feel if their life is not exciting enough to put online it is not as good as their friends or family.

Studies have shown that self comparison on social media can have dire effects on physical and mental health because they give us the ability to seek approval and compare ourselves. Social media has both a practical usage- to connect us with others, but also can lead to fulfillment of gratification. In fact, one study suggests that because a critical aspect of social networking sites involve spending hours, if not months customizing a personal profile, and encourage a sort of social currency based on likes, followers and comments- they provide a forum for persistent "appearance conversations". These appearance centered conversations that forums like Facebook, Instagram among others provide can lead to feelings of disappointment in looks and personality when not enough likes or comments are achieved. In addition, social media use can lead to detrimental physical health effects. A large body of literature associates body image and disordered eating with social networking platforms. Specifically, literature suggests that social media can breed a negative feedback loop of viewing and uploading photos, self comparison, feelings of disappointment when perceived social success is not achieved, and disordered body perception. In fact, one study shows that the microblogging platform, Pinterest is directly associated with disordered dieting behavior, indicating that for those who frequently look at exercise or dieting "pins" there is a greater chance that they will engage in extreme weight-loss and dieting behavior.

Bo Han, a social media researcher at Texas A&M University-Commerce, finds that users are likely to experience the "social media burnout" issue. Ambivalence, emotional exhaustion, and depersonalization are usually the main symptoms if a user experiences social media burnout. Ambivalence refers to a user's confusion about the benefits she can get from using a social media site. Emotional exhaustion refers to the stress a user has when using a social media site. Depersonalization refers to the emotional detachment from a social media site a user experiences. The three burnout factors can all negatively influence the user's social media continuance. This study provides an instrument to measure the burnout a user can experience, when his or her social media "friends" are generating an overwhelming amount of useless information (e.g., "what I had for dinner", "where I am now").

Adolescents

Excessive use of digital technology, like social media, by adolescents can cause disruptions in their physical and mental health, in sleeping patterns, their weight and levels of exercise and notably in their academic performance. Research has continued to demonstrate that long hours spent on mobile devices have shown a positive relationship with an increase in teenagers' BMI and a lack of physical activity. Moreover, excessive internet usage has been linked to lower grades compared to users who do not spend an excessive amount of time online, even with a control over age, gender, race, parent education and personal contentment factors that may affect the study. In a recent study, it was found that time spent on Facebook has a strong negative relationship with overall GPA. The use of multiple social media platforms is more strongly associated with depression and anxiety among young adults than time spent online. The analysis showed that people who reported using the most platforms (7 to 11) had more than three times the risk of depression and anxiety than people who used the fewest (0 to 2). Social media addiction and its sub-dimensions have a high positive correlation. The more the participants are addicted to social media, the less satisfied they are with life. Some parents restrict their children's access to social media for these reasons. There are many ways to combat the negative effects of social media, one being increasing the education teachers and parents of the real harms of social media, as most grew up without the access to social media that adolescents have in 2020.

Sleep disturbances

According to a study released in 2017 by researchers from the University of Pittsburgh, the link between sleep disturbance and the use of social media was clear. It concluded that blue light had a part to play—and how often they logged on, rather than time spent on social media sites, was a higher predictor of disturbed sleep, suggesting "an obsessive 'checking'". The strong relationship of social media use and sleep disturbance has significant clinical ramifications for a young adults health and well-being. In a recent study, we have learned that people in the highest quartile for social media use per week report the most sleep disturbance. The median number of minutes of social media use per day is 61 minutes. Lastly, we have learned that females are more inclined to experience high levels of sleep disturbance than males.

Changes in mood

Many teenagers suffer from sleep deprivation as they spend long hours at night on their phones, and this, in turn, could affect grades as they will be tired and unfocused in school. Social media has generated a phenomenon known as " Facebook depression", which is a type of depression that affects adolescents who spend too much of their free time engaging with social media sites. "Facebook depression" leads to problems such as reclusiveness which can negatively damage ones health by creating feelings of loneliness and low self-esteem among young people. At the same time, a 2017 study shows that there is a link between social media addiction and negative mental health effects. In this study, almost 6,000 adolescent students were examined using the Bergen Social Media Addiction Scale. 4.5% of these students were found to be "at risk" of social media addiction. Furthermore, this same 4.5% reported low self-esteem and high levels of depressive symptoms.

UK researchers used a data set of more than 800 million Twitter messages to evaluate how collective mood changes over the course of 24 hours and across the seasons. The research team collected 800 million anonymous Tweets from 33,576 time points over four years, to examine anger and sadness and compare them with fatigue. The "research revealed strong circadian patterns for both positive and negative moods. The profiles of anger and fatigue were found remarkably stable across the seasons or between the weekdays/weekend." The "positive emotions and sadness showed more variability in response to these changing conditions and higher levels of interaction with the onset of sunlight exposure."

Effects on youth communication

Social media has allowed for mass cultural exchange and intercultural communication. As different cultures have different value systems, cultural themes, grammar, and world views, they also communicate differently. The emergence of social media platforms fused together different cultures and their communication methods, blending together various cultural thinking patterns and expression styles.

Social media has affected the way youth communicate, by introducing new forms of language. Abbreviations have been introduced to cut down on the time it takes to respond online. The commonly known "LOL" has become globally recognized as the abbreviation for "laugh out loud" thanks to social media.

Another trend that influences the way youth communicates is (through) the use of hashtags. With the introduction of social media platforms such as Twitter, Facebook and Instagram, the hashtag was created to easily organize and search for information. Hashtags can be used when people want to advocate for a movement, store content or tweets from a movement for future use, and allow other social media users to contribute to a discussion about a certain movement by using existing hashtags. Using hashtags as a way to advocate for something online makes it easier and more accessible for more people to acknowledge it around the world. As hashtags such as #tbt ("throwback Thursday") become a part of online communication, it influenced the way in which youth share and communicate in their daily lives. Because of these changes in linguistics and communication etiquette, researchers of media semiotics have found that this has altered youth's communications habits and more.

Social media has offered a new platform for peer pressure with both positive and negative communication. From Facebook comments to likes on Instagram, how the youth communicate and what is socially acceptable is now heavily based on social media. Social media does make kids and young adults more susceptible to peer pressure. The American Academy of Pediatrics has also shown that bullying, the making of non-inclusive friend groups, and sexual experimentation have increased situations related to cyberbullying, issues with privacy, and the act of sending sexual images or messages to someone's mobile device. On the other hand, social media also benefits the youth and how they communicate. Adolescents can learn basic social and technical skills that are essential in society. Through the use of social media, kids and young adults are able to strengthen relationships by keeping in touch with friends and family, make more friends, and participate in community engagement activities and services.

Criticism, debate and controversy

Criticisms of social media range from criticisms of the ease of use of specific platforms and their capabilities, disparity of information available, issues with trustworthiness and reliability of information presented, the impact of social media use on an individual's concentration, ownership of media content, and the meaning of interactions created by social media. Although some social media platforms offer users the opportunity to cross-post simultaneously, some social network platforms have been criticized for poor interoperability between platforms, which leads to the creation of information silos, viz. isolated pockets of data contained in one social media platform. However, it is also argued that social media has positive effects, such as allowing the democratization of the Internet while also allowing individuals to advertise themselves and form friendships. Others have noted that the term "social" cannot account for technological features of a platform alone, hence the level of sociability should be determined by the actual performances of its users. There has been a dramatic decrease in face-to-face interactions as more and more social media platforms have been introduced with the threat of cyber-bullying and online sexual predators being more prevalent. Social media may expose children to images of alcohol, tobacco, and sexual behaviors. In regards to cyber-bullying, it has been proven that individuals who have no experience with cyber-bullying often have a better well-being than individuals who have been bullied online.

Twitter is increasingly a target of heavy activity of marketers. Their actions, focused on gaining massive numbers of followers, include use of advanced scripts and manipulation techniques that distort the prime idea of social media by abusing human trustfulness. British-American entrepreneur and author Andrew Keen criticizes social media in his book The Cult of the Amateur, writing, "Out of this anarchy, it suddenly became clear that what was governing the infinite monkeys now inputting away on the Internet was the law of digital Darwinism, the survival of the loudest and most opinionated. Under these rules, the only way to intellectually prevail is by infinite filibustering." This is also relative to the issue "justice" in the social network. For example, the phenomenon "Human flesh search engine" in Asia raised the discussion of "private-law" brought by social network platform. Comparative media professor José van Dijck contends in her book The Culture of Connectivity (2013) that to understand the full weight of social media, their technological dimensions should be connected to the social and the cultural. She critically describes six social media platforms. One of her findings is the way Facebook had been successful in framing the term 'sharing' in such a way that third party use of user data is neglected in favor of intra-user connectedness.

Essena O'Neill attracted international coverage when she explicitly left social media.

Trustworthiness and reliability

There has been speculation that social media has become perceived as a trustworthy source of information by a large number of people. The continuous interpersonal connectivity on social media, for example, may lead to people regarding peer recommendations as indicators of the reliability of information sources. This trust can be exploited by marketers, who can utilize consumer-created content about brands and products to influence public perceptions.

Trustworthiness of information can be improved by fact-checking. Some social media has started to employ this.

Evgeny Morozov, a 2009–2010 Yahoo fellow at Georgetown University, contended that information uploaded to Twitter may have little relevance to the masses of people who do not use Twitter. In an article for the magazine Dissent titled "Iran: Downside to the 'Twitter Revolution'", Morozov wrote:

y its very design Twitter only adds to the noise: it's simply impossible to pack much context into its 140 characters. All other biases are present as well: in a country like Iran it's mostly pro-Western, technology-friendly and iPod-carrying young people who are the natural and most frequent users of Twitter. They are a tiny and, most important, extremely untypical segment of the Iranian population (the number of Twitter users in Iran — a country of more than seventy million people — was estimated at less than twenty thousand before the protests).

In contrast, in the United States (where Twitter originated), the social network had 306 million accounts as of 2012. The number of accounts, though sizable in proportion to the U.S. population of 314.7 million in 2012, may not be fairly comparable, since an undisclosed number of Twitter users operate multiple accounts.

Professor Matthew Auer of Bates College casts doubt on the conventional wisdom that social media are open and participatory. He also speculates on the emergence of "anti-social media" used as "instruments of pure control".

Criticism of data harvesting on Facebook

On April 10, 2018, in a hearing held in response to revelations of data harvesting by Cambridge Analytica, Mark Zuckerberg, the Facebook chief executive, faced questions from senators on a variety of issues, from privacy to the company's business model and the company's mishandling of data. This was Mr. Zuckerberg's first appearance before Congress, prompted by the revelation that Cambridge Analytica, a political consulting firm linked to the Trump campaign, harvested the data of an estimated 87 million Facebook users to psychologically profile voters during the 2016 election. Zuckerburg was pressed to account for how third-party partners could take data without users’ knowledge. Lawmakers grilled the 33-year-old executive on the proliferation of so-called fake news on Facebook, Russian interference during the 2016 presidential election and censorship of conservative media.

Critique of activism

For Malcolm Gladwell, the role of social media, such as Twitter and Facebook, in revolutions and protests is overstated. On one hand, social media make it easier for individuals, and in this case activists, to express themselves. On the other hand, it is harder for that expression to have an impact. Gladwell distinguishes between social media activism and high risk activism, which brings real changes. Activism and especially high-risk activism involves strong-tie relationships, hierarchies, coordination, motivation, exposing oneself to high risks, making sacrifices. Gladwell discusses that social media are built around weak ties and he argues that "social networks are effective at increasing participation — by lessening the level of motivation that participation requires". According to him "Facebook activism succeeds not by motivating people to make a real sacrifice, but by motivating them to do the things that people do when they are not motivated enough to make a real sacrifice".

Disputing Gladwell's theory, in the study "Perceptions of Social Media for Politics: Testing the Slacktivism Hypothesis", Kwak and colleagues conducted a survey which found that people who are politically expressive on social media are also more likely to participate in offline political activity.

Ownership of content

Social media content is generated through social media interactions done by the users through the site. There has always been a huge debate on the ownership of the content on social media platforms because it is generated by the users and hosted by the company. Added to this is the danger to security of information, which can be leaked to third parties with economic interests in the platform, or parasites who comb the data for their own databases.

Privacy

Main article: Privacy concerns with social networking servicesPrivacy rights advocates warn users on social media about the collection of their personal data. Some information is captured without the user's knowledge or consent through electronic tracking and third party applications. Data may also be collected for law enforcement and governmental purposes, by social media intelligence using data mining techniques. Data and information may also be collected for third party use. When information is shared on social media, that information is no longer private. There have been many cases in which young persons especially, share personal information, which can attract predators. It is very important to monitor what you share, and to be aware of who you could potentially be sharing that information with. Teens especially share significantly more information on the internet now than they have in the past. Teens are much more likely to share their personal information, such as email address, phone number, and school names. Studies suggest that teens are not aware of what they are posting and how much of that information can be accessed by third parties.

There are arguments that "privacy is dead" and that with social media growing more and more, some heavy social media users appear to have become quite unconcerned with privacy. Others argue, however, that people are still very concerned about their privacy, but are being ignored by the companies running these social networks, who can sometimes make a profit off of sharing someone's personal information. There is also a disconnect between social media user's words and their actions. Studies suggest that surveys show that people want to keep their lives private, but their actions on social media suggest otherwise. Another factor is ignorance of how accessible social media posts are. Some social media users who have been criticized for inappropriate comments stated that they did not realize that anyone outside their circle of friends would read their post; in fact, on some social media sites, unless a user selects higher privacy settings, their content is shared with a wide audience.

According to a 2016 article diving into the topic of sharing privately and the effect social media has on expectations of privacy, "1.18 billion people will log into their Facebook accounts, 500 million tweets will be sent, and there will be 95 million photos and videos posted on Instagram" in a day. Much of the privacy concerns individuals face stem from their own posts on a form of social network. Users have the choice to share voluntarily, and has been ingrained into society as routine and normative. Social media is a snapshot of our lives; a community we have created on the behaviors of sharing, posting, liking, and communicating. Sharing has become a phenomenon which social media and networks have uprooted and introduced to the world. The idea of privacy is redundant; once something is posted, its accessibility remains constant even if we select who is potentially able to view it. People desire privacy in some shape or form, yet also contribute to social media, which makes it difficult to maintain privacy. Mills offers options for reform which include copyright and the application of the law of confidence; more radically, a change to the concept of privacy itself.

A 2014 Pew Research Center survey found that 91% of Americans "agree" or "strongly agree" that people have lost control over how personal information is collected and used by all kinds of entities. Some 80% of social media users said they were concerned about advertisers and businesses accessing the data they share on social media platforms, and 64% said the government should do more to regulate advertisers.

According to the wall street journal published on February 17, 2019 According to the UK law, Facebook did not protect certain aspects of the user data.

Criticism of commercialization

The commercial development of social media has been criticized as the actions of consumers in these settings has become increasingly value-creating, for example when consumers contribute to the marketing and branding of specific products by posting positive reviews. As such, value-creating activities also increase the value of a specific product, which could, according to the marketing professors Bernad Cova and Daniele Dalli, lead to what they refer to as "double exploitation". Companies are getting consumers to create content for the companies' websites for which the consumers are not paid.

As social media usage has become increasingly widespread, social media has to a large extent come to be subjected to commercialization by marketing companies and advertising agencies. Christofer Laurell, a digital marketing researcher, suggested that the social media landscape currently consists of three types of places because of this development: consumer-dominated places, professionally dominated places and places undergoing commercialization. As social media becomes commercialized, this process have been shown to create novel forms of value networks stretching between consumer and producer in which a combination of personal, private and commercial contents are created.

Debate over addiction