This is an old revision of this page, as edited by AAA765 (talk | contribs) at 13:26, 9 January 2007 (→Antisemitism and the Muslim world: this is like an intro giving different opinions about the very question of relation of Islam and antisemitism). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 13:26, 9 January 2007 by AAA765 (talk | contribs) (→Antisemitism and the Muslim world: this is like an intro giving different opinions about the very question of relation of Islam and antisemitism)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) This article describes the development and history of traditional antisemitism. A separate article exists on the more recent concept of New antisemitism.Antisemitism (alternatively spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility toward or prejudice against Jews as a religious, racial, or ethnic group, which can range in expression from individual hatred to institutionalized, violent persecution. While the term's etymology may imply that antisemitism is directed against all Semitic peoples, it is in practice used exclusively to refer to hostility towards Jews. The highly explicit ideology of Adolf Hitler's Nazism was the most extreme example of this phenomenon, leading to the Holocaust.

Antisemitism can be broadly categorized into three forms:

- Religious antisemitism, also known as anti-Judaism. As the name implies, it was the practice of Judaism itself that was the defining characteristic of the antisemitic attacks. Under this version of antisemitism, attacks would often stop if Jews stopped practising or changed their public faith, especially by conversion to the "official" or "right" religion, and sometimes, liturgal exclusion of Jewish converts (the case of Christianized Marranos or Spanish Jews in the late 15th and 16th centuries convicted of secretly practising Judaism or Jewish customs).

- Racial antisemitism. Either a pre-cursor or by-product of the eugenics movement, racial antisemitism replaced hatred of the Jewish religion with the concept that the Jews themselves were a distinct and inferior race. Also included in this category of antisemitism are statements of the Jews' "alien" extra-European origins. (See the numerous anthropological theories on if the Jews possessed any Arabic-Armenoid, African-Nubian or Asian-Turkic ancestries.) Racial antisemitic beliefs are major emphases of the Neo-Nazi and include white supremacist movements in the late 20th century.

- New antisemitism is the concept of a new form of 21st century antisemitism coming simultaneously from the left, the far right, and radical Islam, which tends to focus on opposition to the emergence of a Jewish homeland in the State of Israel. The concept has been criticized for what some authors see as a confusion of antisemitism and anti-Zionism.

Etymology and usage

Semite refers broadly to speakers of a language group which includes both Arabs and Jews. However, the term antisemitism is specifically used in reference to attitudes held towards Jews.

The word antisemitic (antisemitisch in German) was probably first used in 1860 by the Austrian Jewish scholar Moritz Steinschneider in the phrase "antisemitic prejudices" (Template:Lang-de). Steinschneider used this phrase to characterize Ernest Renan's ideas about how "Semitic races" were inferior to "Aryan races." These pseudo-scientific theories concerning race, civilization, and "progress" had become quite widespread in Europe in the second half of the 19th century, especially as Prussian nationalistic historian Heinrich von Treitschke did much to promote this form of racism. In Treitschke's writings Semitic was practically synonymous with Jewish, in contrast to its usage by Renan and others.

German political agitator Wilhelm Marr coined the related German word Antisemitismus in his book "The Way to Victory of Germanicism over Judaism" in 1879. Marr used the phrase to mean hatred of Jews or Judenhass, and he used the new word antisemitism to make hatred of the Jews seem rational and sanctioned by scientific knowledge. Marr's book became very popular, and in the same year he founded the "League of Antisemites" ("Antisemiten-Liga"), the first German organization committed specifically to combatting the alleged threat to Germany posed by the Jews, and advocating their forced removal from the country.

So far as can be ascertained, the word was first widely printed in 1881, when Marr published "Zwanglose Antisemitische Hefte," and Wilhelm Scherer used the term "Antisemiten" in the "Neue Freie Presse" of January. The related word semitism was coined around 1885. See also the coinage of the term "Palestinian" by Germans to refer to the nation or people known as Jews, as distinct from the religion of Judaism.

Despite the use of the prefix "anti," the terms Semitic and anti-Semitic are not directly opposed to each other (unlike similar-seeming terms such as anti-American or anti-Hellenic). To avoid the confusion of the misnomer, many scholars on the subject (such as Emil Fackenheim) now favor the unhyphenated antisemitism in order to emphasize that the word should be read as a single unified term, not as a meaningful root word-prefix combination.

In fact, the term antisemitism has historically referred to prejudice towards Jews alone, and this was the only use of the word for more than a century. It does not traditionally refer to prejudice toward other people who speak Semitic languages (e.g. Arabs or Assyrians). Bernard Lewis, Professor of Near Eastern Studies Emeritus at Princeton University, says that "Antisemitism has never anywhere been concerned with anyone but Jews." Yehuda Bauer articulated this view in his writings and lectures: (the term) "Antisemitism, especially in its hyphenated spelling, is inane nonsense, because there is no Semitism that you can be anti to."

In recent decades some groups have argued that the term should be extended to include prejudice against Arabs or Anti-Arabism, in the context of answering accusations of Arab antisemitism; further, some, including the Islamic Association of Palestine, have argued that this implies that Arabs cannot, by definition, be antisemitic. The argument for such an extension of meaning comes from the claim that since the Semitic language family includes Arabic, Hebrew and Aramaic languages and the historical term "Semite" refers to all those who consider themselves descendants of the Biblical Shem, "anti-Semitism" should be likewise inclusive. However, this usage is not generally accepted.

Definitions of the term

Though the general definition of antisemitism is hostility or prejudice towards Jews, a number of authorities have developed more formal definitions. Holocaust scholar and City University of New York professor Helen Fein's definition has been particularly influential. She defines antisemitism as "a persisting latent structure of hostile beliefs towards Jews as a collective manifested in individuals as attitudes, and in culture as myth, ideology, folklore and imagery, and in actions – social or legal discrimination, political mobilisation against the Jews, and collective or state violence – which results in and/or is designed to distance, displace, or destroy Jews as Jews."

Professor Dietz Bering of the University of Cologne further expanded on Professor Fein's definition by describing the structure of antisemitic beliefs. To antisemites, "Jews are not only partially but totally bad by nature, that is, their bad traits are incorrigible. Because of this bad nature: (1) Jews have to be seen not as individuals but as a collective. (2) Jews remain essentially alien in the surrounding societies. (3) Jews bring disaster on their 'host societies' or on the whole world, they are doing it secretly, therefore the antisemites feel obliged to unmask the conspiratorial, bad Jewish character."

There have been a number of efforts by international and governmental bodies to formally define antisemitism. The United States Department of State defines antisemitism in its 2005 Report on Global Anti-Semitism as "hatred toward Jews — individually and as a group — that can be attributed to the Jewish religion and/or ethnicity."

In 2005, the European Monitoring Centre on Racism and Xenophobia (EUMC), a body of the European Union, developed a more detailed working definition: "Antisemitism is a certain perception of Jews, which may be expressed as hatred toward Jews. Rhetorical and physical manifestations of antisemitism are directed toward Jewish or non-Jewish individuals and/or their property, toward Jewish community institutions and religious facilities. In addition, such manifestations could also target the state of Israel, conceived as a Jewish collectivity. Antisemitism frequently charges Jews with conspiring to harm humanity, and it is often used to blame Jews for 'why things go wrong'."

The EUMC then listed "contemporary examples of antisemitism in public life, the media, schools, the workplace, and in the religious sphere." These included: Making mendacious, dehumanizing, demonizing, or stereotypical allegations about Jews; accusing Jews as a people of being responsible for real or imagined wrongdoing committed by a single Jewish person or group; denying the Holocaust; and accusing Jewish citizens of being more loyal to Israel, or to the alleged priorities of Jews worldwide, than to the interests of their own nations. The EUMC also discussed ways in which attacking Israel could be antisemitic, depending on the context (see anti-Zionism below).

Emotionality of the term

Before the extent of the Nazi genocide became widely known and the term "antisemitism" acquired emotional connotations, it was not uncommon for a person to self-identify as an antisemite. In 1879 Wilhelm Marr founded the Antisemiten-Liga. In 1895 A. C. Cuza organized the Alliance Anti-semitique Universelle in Bucharest. In the aftermath of Kristallnacht, Goebbels announced: "The German people is anti-Semitic. It has no desire to have its rights restricted or to be provoked in the future by parasites of the Jewish race."

Earliest antisemitism

The earliest occurrence of Antisemitism has been the subject of debate among scholars. Professor Peter Schafer of the Freie University of Berlin has argued that antisemitism was first spread by "the Greek retelling of ancient Egyptian prejudices". In view of the anti-Jewish writings of the Egyptian priest Manetho, Schafer suggests that antisemitism may have emerged "in Egypt alone".

Father Edward H. Flannery, in The Anguish of the Jews: Twenty-Three Centuries of Antisemitism, traces what he calls the first clear examples of anti-Jewish sentiment, which he calls "antisemitism," to third century BCE Alexandria. Hecataetus of Abdera, a Greek historian, wrote that Moses "in remembrance of the exile of his people, instituted for them a misanthropic and inhospitable way of life." Manetho, an Egyptian priest and historian, wrote that the Jews were expelled Egyptian lepers who had been taught by Moses "not to adore the gods." The same themes appeared in the works of Chaeremon, Lysimachus, Poseidonius, Apollonius Molon, and in Apion and Tacitus, according to Flannery. Agatharchides of Cnidus wrote about the "ridiculous practises" of the Jews and of the "absurdity of their Law," making a mocking reference to how Ptolemy Lagus was able to invade Jerusalem in 320 BCE because its inhabitants were observing the Sabbath.

The hostility commonly faced by Jews in the Diaspora has been extensively described by John M. G. Barclay of the University of Durham. The ancient Jewish philosopher Philo of Alexandria described an attack on Jews in Alexandria in 38 CE in Flaccus, in which thousands of Jews died. In the analysis of Pieter W. Van Der Horst, the cause of the violence in Alexandria was that Jews had been portrayed as misanthropes. Gideon Bohak has argued that early animosity against Jews was not anti-Judaism unless it arose from attitudes held against Jews alone. Using this stricter definition, Bohak says that many Greeks had animosity toward any group they regarded as barbarians. The 150 BCE suppression of Jewish religious practice by use of deadly force against civilians, as recounted in 1 Maccabees, then qualifies as anti-Judaism in a broader sense of the term than is used by Bohak. There are other examples of ancient animosity towards Jews that are not considered by all to fall within the definition of antisemitism.

Religious antisemitism

Main article: Religious antisemitismAntisemitism and the Christian world

Main article: Christianity and antisemitismAnti-Judaism in the New Testament

The New Testament is a collection of books written by various authors. Most of this collection was written by the end of the first century. The majority of the New Testament was written by Jews who became followers of Jesus, and all but two books (Luke and Acts) are traditionally attributed to such Jewish followers. Nevertheless, there are a number of passages in the New Testament that some see as antisemitic, or have been used for antisemitic purposes, most notably:

- Jesus speaking to a group of Pharisees: "I know that you are descendants of Abraham; yet you seek to kill me, because my word finds no place in you. I speak of what I have seen with my Father, and you do what you have heard from your father. They answered him, "Abraham is our father." Jesus said to them, "If you were Abraham's children, you would do what Abraham did. ... You are of your father the devil, and your will is to do your father's desires. He was a murderer from the beginning, and has nothing to do with the truth, because there is no truth in him. When he lies, he speaks according to his own nature, for he is a liar and the father of lies. But, because I tell the truth, you do not believe me. Which of you convicts me of sin? If I tell the truth, why do you not believe me? He who is of God hears the words of God; the reason why you do not hear them is you are not of God." (John 8:37-39, 44-47, RSV)

- Stephen speaking before a synagogue council just before his execution: "You stiff-necked people, uncircumcised in heart and ears, you always resist the Holy Spirit. As your fathers did, so do you. Which of the prophets did not your fathers persecute? And they killed those who announced beforehand the coming of the Righteous One, whom you have now betrayed and murdered, you who received the law as delivered by angels and did not keep it." (Acts 7:51-53, RSV)

- "Behold, I will make those of the synagogue of Satan who say that they are Jews and are not, but lie — behold, I will make them come and bow down before your feet, and learn that I have loved you." (Revelation 3:9, RSV).

Some biblical scholars point out that Jesus and Stephen are presented as Jews speaking to other Jews, and that their use of broad accusation against Israel is borrowed from Moses and the later Jewish prophets (e.g. Deut 9:13-14; 31:27-29; 32:5, 20-21; 2 Kings 17:13-14; Is 1:4; Hos 1:9; 10:9). Jesus once calls his own disciple Peter 'Satan' (Mk 8:33). Other scholars hold that verses like these reflect the Jewish-Christian tensions that were emerging in the late first or early second century, and do not originate with Jesus. Today, nearly all Christian denominations de-emphasize verses such as these, and reject their use and misuse by antisemites.

Drawing from the Jewish prophet Jeremiah (Jeremiah 31:31-34), the New Testament taught that with the death of Jesus a new covenant was established which rendered obsolete and in many respects superseded the first covenant established by Moses (Hebrews 8:7-13; Lk 22:20). Observance of the earlier covenant traditionally characterizes Judaism. This New Testament teaching, and later variations to it, are part of what is called supersessionism. However, the early Jewish followers of Jesus continued to practice circumcision and observe dietary laws, which is why the failure to observe these laws by the first Gentile Christians became a matter of controversy and dispute some years after Jesus' death (Acts 11:3; 15:1ff; 16:3).

The New Testament holds that Jesus' (Jewish) disciple Judas Iscariot (Mark14:43-46), the Roman governor Pontius Pilate along with Roman forces (John 19:11; Acts 4:27) and Jewish leaders and people of Jerusalem were (to varying degrees) responsible for the death of Jesus (Acts 13:27); Diaspora Jews are not blamed for events which were clearly outside their control.

After Jesus' death, the New Testament portrays the Jewish religious authorities in Jerusalem as hostile to Jesus' followers, and as occasionally using force against them. Stephen is executed by stoning (Acts 7:58). Before his conversion, Saul puts followers of Jesus in prison (Acts 8:3; Galatians 1:13-14; 1 Timothy 1:13). After his conversion, Saul is whipped at various times by Jewish authorities (2 Corinthians 11:24), and is accused by Jewish authorities before Roman courts (e.g., Acts 25:6-7). However, opposition from Gentiles is also cited repeatedly (2 Corinthians 11:26; Acts 16:19ff; 19:23ff). More generally, there are widespread references in the New Testament to suffering experienced by Jesus' followers at the hands of others (Romans 8:35; 1 Corinthians 4:11ff; Galatians 3:4; 2 Thessalonians 1:5; Hebrews 10:32; 1 Peter 4:16; Revelation 20:4).

See Joseph Atwill's interview on the The Roots of Anti-Semitism[

Early Christianity

A number of early and influential Church works — such as the dialogues of Justin Martyr, the homilies of John Chrysostom, and the testimonies of church father Cyprian — are strongly anti-Jewish.

During a discussion on the celebration of Easter during the First Council of Nicaea in AD 325, Roman emperor Constantine said,

...it appeared an unworthy thing that in the celebration of this most holy feast we should follow the practice of the Jews, who have impiously defiled their hands with enormous sin, and are, therefore, deservedly afflicted with blindness of soul. (...) Let us then have nothing in common with the detestable Jewish crowd; for we have received from our Saviour a different way.

Prejudice against Jews in the Roman Empire was formalized in 438, when the Code of Theodosius II established Roman Catholic Christianity as the only legal religion in the Roman Empire. The Justinian Code a century later stripped Jews of many of their rights, and Church councils throughout the sixth and seventh century, including the Council of Orleans, further enforced anti-Jewish provisions. These restrictions began as early as 305, when, in Elvira, (now Granada), a Spanish town in Andalusia, the first known laws of any church council against Jews appeared. Christian women were forbidden to marry Jews unless the Jew first converted to Catholicism. Jews were forbidden to extend hospitality to Catholics. Jews could not keep Catholic Christian concubines and were forbidden to bless the fields of Catholics. In 589, in Catholic Spain, the Third Council of Toledo ordered that children born of marriage between Jews and Catholic be baptized by force. By the Twelfth Council of Toledo (681) a policy of forced conversion of all Jews was initiated (Liber Judicum, II.2 as given in Roth). Thousands fled, and thousands of others converted to Roman Catholicism.

Antisemitism in Europe (Middle Ages)

Accusations of deicide

Further information: ]In the Middle Ages a main justification of prejudice against Jews in Europe was religious. Though not part of Roman Catholic dogma, many Christians, including members of the clergy, have held the Jewish people collectively responsible for killing Jesus, a practice originated by Melito of Sardis. As stated in the Boston College Guide to Passion Plays, "Over the course of time, Christians began to accept... that the Jewish people as a whole were responsible for killing Jesus. According to this interpretation, both the Jews present at Jesus’ death and the Jewish people collectively and for all time, have committed the sin of deicide, or God-killing. For 1900 years of Christian-Jewish history, the charge of deicide has led to hatred, violence against and murder of Jews in Europe and America." This accusation was repudiated in 1964, when the Catholic Church under Pope Paul VI issued the document Nostra Aetate as a part of Vatican II.

Restrictions to marginal occupations (tax collecting, moneylending, etc.)

Among socio-economic factors were restrictions by the authorities. Local rulers and church officials closed many professions to the Jews, pushing them into marginal occupations considered socially inferior, such as tax and rent collecting and moneylending, tolerated then as a "necessary evil". Catholic doctrine of the time held that lending money for interest was a sin, and forbidden to Christians. Not being subject to this restriction, Jews dominated this business. The Torah and later sections of the Hebrew Bible criticise Usury but interpretations of the Biblical prohibition vary. Since few other occupations were open to them, Jews were motivated to take up money lending. This was said to show Jews were insolent, greedy, usurers, and subsequently lead to many negative stereotypes and propaganda. Natural tensions between creditors (typically Jews) and debtors (typically Christians) were added to social, political, religious, and economic strains. Peasants who were forced to pay their taxes to Jews could personify them as the people taking their earnings while remaining loyal to the lords on whose behalf the Jews worked.

The Black Death

Further information: Black DeathAs the Black Death epidemics devastated Europe in the mid-14th century, annihilating more than a half of the population, Jews were taken as scapegoats. Rumors spread that they caused the disease by deliberately poisoning wells. Hundreds of Jewish communities were destroyed by violence, in particular in the Iberian peninsula and in the Germanic Empire. In Provence, 40 Jews were burnt in Toulon as soon as April 1348. "Never mind that Jews were not immune from the ravages of the plague ; they were tortured until they "confessed" to crimes that they could not possibly have committed. In one such case, a man named Agimet was ... coerced to say that Rabbi Peyret of Chambery (near Geneva) had ordered him to poison the wells in Venice, Toulouse, and elsewhere. In the aftermath of Agimet’s "confession," the Jews of Strasbourg were burned alive on February 14, 1349.

Although the Pope Clement VI tried to protect them by the July 6, 1348 papal bull and another 1348 bull, several months later, 900 Jews were burnt in Strasbourg, where the plague hadn't yet affected the city. Clement VI condemned the violence and said those who blamed the plague on the Jews (among whom were the flagellants) had been "seduced by that liar, the Devil."

The demonizing of the Jews

From around the 12th century through the 19th there were Christians who believed that some (or all) Jews possessed magical powers; some believed that they had gained these magical powers from making a deal with the devil. See also Judensau, Judeophobia.

Blood libels

Main articles: blood libel, list of blood libels against Jews

On many occasions, Jews were accused of a blood libel, the supposed drinking of blood of Christian children in mockery of the Christian Eucharist. (Early Christians had been accused of a similar practice based on pagan misunderstanding of the Eucharist ritual.) According to the authors of these blood libels, the 'procedure' for the alleged sacrifice was something like this: a child who had not yet reached puberty was kidnapped and taken to a hidden place. The child would be tortured by Jews, and a crowd would gather at the place of execution (in some accounts the synagogue itself) and engage in a mock tribunal to try the child. The child would be presented to the tribunal naked and tied and eventually be condemned to death. In the end, the child would be crowned with thorns and tied or nailed to a wooden cross. The cross would be raised, and the blood dripping from the child's wounds would be caught in bowls or glasses and then drunk. Finally, the child would be killed with a thrust through the heart from a spear, sword, or dagger. Its dead body would be removed from the cross and concealed or disposed of, but in some instances rituals of black magic would be performed on it. This method, with some variations, can be found in all the alleged Christian descriptions of ritual murder by Jews.

The story of William of Norwich (d. 1144) is the first known case of ritual murder being alleged by a Christian monk, while the story of Little Saint Hugh of Lincoln (d. 1255) said that after the boy was dead, his body was removed from the cross and laid on a table. His belly was cut open and his entrails removed for some occult purpose, such as a divination ritual. The story of Simon of Trent (d. 1475) emphasized how the boy was held over a large bowl so all his blood could be collected. Simon was regarded as a saint, and was canonized by Pope Sixtus V in 1588. The cult of Simon was disbanded in 1965 by Pope Paul VI, and the shrine erected to him was dismantled. He was removed from the calendar, and his future veneration was forbidden, though a handful of extremists still promote the narrative as a fact. In the 20th century, the Beilis Trial in Russia and the Kielce pogrom represented incidents of blood libel in Europe. Unproved rumours of Jews killing Christians were used as justification for killing of Jews by Christians.

More recently blood libel stories have appeared a number of times in the state-sponsored media of a number of Arab nations, in Arab television shows, and on websites.

Host desecration

Jews were sometimes falsely accused of desecrating consecrated hosts in a reenactment of the Crucifixion; this crime was known as host desecration and carried the death penalty.

Disabilities and restrictions

Jews were subject to a wide range of legal restrictions throughout the Middle Ages, some of which lasted until the end of the 19th century. Jews were excluded from many trades, the occupations varying with place and time, and determined by the influence of various non-Jewish competing interests. Often Jews were barred from all occupations but money-lending and peddling, with even these at times forbidden. The number of Jews permitted to reside in different places was limited; they were concentrated in ghettos, and were not allowed to own land; they were subject to discriminatory taxes on entering cities or districts other than their own, were forced to swear special Jewish Oaths, and suffered a variety of other measures, including restrictions on dress.

Clothing

Main article: yellow badge, Judenhut

The Fourth Lateran Council in 1215 was the first to proclaim the requirement for Jews to wear something that distinguished them as Jews. It could be a coloured piece of cloth in the shape of a star or circle or square, a hat (Judenhut), or a robe. In many localities, members of the medieval society wore badges to distinguish their social status. Some badges (such as guild members) were prestigious, while others ostracised outcasts such as lepers, reformed heretics and prostitutes. Jews sought to evade the badges by paying what amounted to bribes in the form of temporary "exemptions" to kings, which were revoked and re-paid whenever the king needed to raise funds.

The Crusades

The Crusades were a series of several military campaigns sanctioned by the Papacy that took place during the 11th through 13th centuries. They began as Catholic endeavors to recapture Jerusalem from the Muslims but developed into territorial wars.

The mobs accompanying the first three Crusades, and particularly the People's Crusade accompanying the first Crusade, attacked the Jewish communities in Germany, France, and England, and put many Jews to death. Entire communities, like those of Treves, Speyer, Worms, Mayence, and Cologne, were slain during the first Crusade by a mob army. About 12,000 Jews are said to have perished in the Rhenish cities alone between May and July, 1096. Before the Crusades the Jews had practically a monopoly of trade in Eastern products, but the closer connection between Europe and the East brought about by the Crusades raised up a class of merchant traders among the Christians, and from this time onward restrictions on the sale of goods by Jews became frequent. The religious zeal fomented by the Crusades at times burned as fiercely against the Jews as against the Muslims, though attempts were made by bishops during the First crusade and the papacy during the Second Crusade to stop Jews from being attacked. Both economically and socially the Crusades were disastrous for European Jews. They prepared the way for the anti-Jewish legislation of Pope Innocent III, and formed the turning point in the medieval history of the Jews.

The expulsions from England, France, Germany, and Spain

Only a few expulsions of the Jews are described in this section, for a more extended list see History of antisemitism, and also the History of the Jews in England, Germany, Spain, and France.

The practice of expelling the Jews accompanied by confiscation of their property, followed by temporary readmissions for ransom, was utilized to enrich the French crown during 12th-14th centuries. The most notable such expulsions were: from Paris by Philip Augustus in 1182, from the entirety of France by Louis IX in 1254, by Charles IV in 1306, by Charles V in 1322, by Charles VI in 1394.

To finance his war to conquer Wales, Edward I of England taxed the Jewish moneylenders. When the Jews could no longer pay, they were accused of disloyalty. Already restricted to a limited number of occupations, the Jews saw Edward abolish their "privilege" to lend money, choke their movements and activities and were forced to wear a yellow patch. The heads of Jewish households were then arrested, over 300 of them taken to the Tower of London and executed, while others killed in their homes. See also:-Massacres at London and York (1189 – 1190). The complete banishment of all Jews from the country in 1290 led to thousands killed and drowned while fleeing and the absence of Jews from England for three and a half centuries, until 1655, when Oliver Cromwell reversed the policy.

In 1492, Ferdinand II of Aragon and Isabella of Castile issued General Edict on the Expulsion of the Jews from Spain (see also Spanish Inquisition) and many Sephardi Jews fled to the Ottoman Empire, some to the Land of Israel.

In 1744, Frederick II of Prussia limited Breslau to only ten so-called "protected" Jewish families and encouraged similar practice in other Prussian cities. In 1750 he issued Revidiertes General Privilegium und Reglement vor die Judenschaft: the "protected" Jews had an alternative to "either abstain from marriage or leave Berlin" (quoting Simon Dubnow). In the same year, Archduchess of Austria Maria Theresa ordered Jews out of Bohemia but soon reversed her position, on condition that Jews pay for readmission every ten years. This extortion was known as malke-geld (queen's money). In 1752 she introduced the law limiting each Jewish family to one son. In 1782, Joseph II abolished most of persecution practices in his Toleranzpatent, on the condition that Yiddish and Hebrew are eliminated from public records and judicial autonomy is annulled. Moses Mendelssohn wrote that "Such a tolerance... is even more dangerous play in tolerance than open persecution".

Anti-Judaism and the Reformation

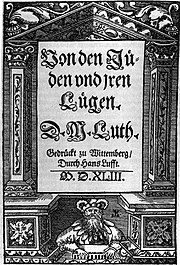

Martin Luther, an Augustinian monk and an ecclesiastical reformer whose teachings inspired the Reformation, wrote antagonistically about Jews in his book On the Jews and their Lies, which describes the Jews in extremely harsh terms, excoriates them, and provides detailed recommendations for a pogrom against them and their permanent oppression and/or expulsion. According to Paul Johnson, it "may be termed the first work of modern antisemitism, and a giant step forward on the road to the Holocaust." In his final sermon shortly before his death, however, Luther preached "We want to treat them with Christian love and to pray for them, so that they might become converted and would receive the Lord." Still, Luther's harsh comments about the Jews are seen by many as a continuation of medieval Christian antisemitism. See also Martin Luther and Antisemitism

Antisemitism in 19th and 20th century (Catholicism)

Throughout the 19th century and into the 20th, the Catholic Church still incorporated strong antisemitic elements, despite increasing attempts to separate anti-Judaism, the opposition to the Jewish religion on religious grounds, and racial antisemitism. Pope Pius VII (1800-1823) had the walls of the Jewish Ghetto in Rome rebuilt after the Jews were released by Napoleon, and Jews were restricted to the Ghetto through the end of the papacy of Pope Pius IX (1846-1878), the last Pope to rule Rome. Additionally, official organizations such as the Jesuits banned candidates "who are descended from the Jewish race unless it is clear that their father, grandfather, and great-grandfather have belonged to the Catholic Church" until 1946. Brown University historian David Kertzer, working from the Vatican archive, has further argued in his book The Popes Against the Jews that in the 19th and 20th century the Roman Catholic Church adhered to a distinction between "good antisemitism" and "bad antisemitism". The "bad" kind promoted hatred of Jews because of their descent. This was considered un-Christian because the Christian message was intended for all of humanity regardless of ethnicity; anyone could become a Christian. The "good" kind criticized alleged Jewish conspiracies to control newspapers, banks, and other institutions, to care only about accumulation of wealth, etc. Many Catholic bishops wrote articles criticizing Jews on such grounds, and, when accused of promoting hatred of Jews, would remind people that they condemned the "bad" kind of antisemitism. Kertzer's work is not, therefore, without critics; scholar of Jewish-Christian relations Rabbi David G. Dalin, for example, criticized Kertzer in the Weekly Standard for using evidence selectively. The Second Vatican Council, the Nostra Aetate document, and the efforts of Pope John Paul II have helped reconcile Jews and Catholicism in recent decades, however.

Passion plays

Passion plays, dramatic stagings representing the trial and death of Jesus, have historically been used in remembrance of Jesus' death during Lent. These plays historically blamed the Jews for the death of Jesus in a polemical fashion, depicting a crowd of Jewish people condemning Jesus to crucifixion and a Jewish leader assuming eternal collective guilt for the crowd for the murder of Jesus, which, The Boston Globe explains, "for centuries prompted vicious attacks — or pogroms — on Europe's Jewish communities". Time magazine in its article, The Problem With Passion, explains that "such passages (are) highly subject to interpretation". Although modern scholars interpret the "blood on our children" (Matthew 27:25) as "a specific group's oath of responsibility" some audiences have historically interpreted it as "an assumption of eternal, racial guilt". This last interpretation has often incited violence against Jews; according to the Anti-Defamation League, "Passion plays historically unleashed the torrents of hatred aimed at the Jews, who always were depicted as being in partnership with the devil and the reason for Jesus' death". The Christian Science Monitor, in its article, Capturing the Passion, explains that "istorically, productions have reflected negative images of Jews and the long-time church teaching that the Jewish people were collectively responsible for Jesus' death. Violence against Jews as 'Christ-killers' often flared in their wake." Christianity Today in Why some Jews fear The Passion (of the Christ) observed that "Outbreaks of Christian antisemitism related to the Passion narrative have been...numerous and destructive." The Religion Newswriters Association observed that

- "in Easter 2001, three incidents made national headlines and renewed their fears. One was a column by Paul Weyrich, a conservative Christian leader and head of the Free Congress Foundation, who argued that "Christ was crucified by the Jews." Another was sparked by comments from the NBA point guard and born-again Christian Charlie Ward, who said in an interview that Jews were persecuting Christians and that Jews "had his blood on their hands." Finally, the evangelical Christian comic strip artist Johnny Hart published a B.C. strip that showed a menorah disintegrating until it became a cross, with each panel featuring the last words of Jesus, including "Father, forgive them, for they know not what they do."

In 1988, the Bishops' Committee for Ecumenical and Interreligious Affairs of the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops published Criteria for the Evaluation of Dramatizations of the Passion, in order to ensure that Passion Plays adhere to the teaching of the Second Vatican Council and the Pontifical Biblical Commission as expressed in Nostra Aetate no. 4 (October 28, 1965). These criteria were summarized for the Archdiocese of Boston as:

- The overriding preoccupation of any dramatization of the Passion must be, in the words of Ellis Rivkin, not who killed Christ, but what killed Christ, namely, our sins.

- Those scripting a Passion play must use the best available biblical scholarship to elucidate the gospel texts which were not written to preserve historical facts so much as to proclaim the saving truth about Jesus.

- Harmonizing the four accounts of Jesus’ Passion — i.e. constructing a single story of the Passion by combining elements from the four gospel versions — risks violating the integrity of the texts, each of which offers a distinct theological interpretation of Jesus ’ death.

- Because of the nature of the gospels, the choice of what gospel passages to use in the making of a Passion play must be guided by the Church’s teaching that “the Jews should not be presented as rejected or accursed by God as if this followed from Sacred Scripture” (Nostra Aetate 4). The claim that a passage is “in the Bible” does not suffice to justify its inclusion.

- As ignorance of Judaism often leads to misinterpretation of events, the complexity of the Jewish world of Jesus must be carefully researched and correctly represented; e.g., it is important to know that the high priest was appointed by the Roman procurator.

- Crowd scenes must represent this rich diversity and reflect a range of responses to Jesus among the crowd as among their leaders.

- The Jewishness of Jesus and his followers must be taken seriously. They must be portrayed as Jews among Jews and not set apart by means of costuming or makeup.

- Stereotypes of Jews and Judaism (e.g. depicting Jews as avaricious) must be avoided.

- The Pharisees are not mentioned in the gospel accounts of Jesus’ Passion and therefore should not be depicted as responsible for his death. The Jews most directly implicated in the death of Jesus are the Temple priests.

- Roman soldiers should be on stage throughout the play to keep before the audience the pervasive and oppressive reality of Roman occupation.

- Problematic passages, like Matthew’s “his blood be on us and on our children” (27:25), that can be misconstrued as blaming all Jews of all time for the death of Jesus, should be omitted. As a general rule in these cases, the Bishops suggest that “if one cannot show beyond reasonable doubt that the particular gospel element selected or paraphrased will not be offensive or have the potential for negative influence on the audience for whom the presentation is intended, the element cannot, in good conscience, be used” (“Criteria,” p. 12).

On January 6, 2004, the Consultative Panel on Lutheran-Jewish Relations of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America similarly issued a statement urging any Lutheran church presenting a Passion Play to adhere to their Guidelines for Lutheran-Jewish Relations, stating that "the New Testament . . . must not be used as justification for hostility towards present-day Jews," and that "blame for the death of Jesus should not be attributed to Judaism or the Jewish people."

In 2003 and 2004 some compared Mel Gibson's recent film The Passion of the Christ to these kinds of passion plays, but this characterization is hotly disputed; an analysis of that topic is in the article on The Passion of the Christ. Despite such fears, there have been no publicized antisemitic incidents directly attributable to the movie's influence. However, the film's reputation for antisemitism led to the movie being distributed and well-received throughout the Muslim world, even in nations that typically suppress public expressions of Christianity.

Antisemitism and the Muslim world

Main article: Islam and antisemitism See also: Arabs and antisemitismClaude Cahen argues that, while prejudice and hostility existed in the Islamic world, there was no antisemitism since there was scarcely any difference in the treatment accorded to Christians and Jews. Bernard Lewis holds that there was no antisemitism because there was no attribution of cosmic evil to Jews. S. D. Goitein argues that anti-semitism was not entirely absent as it is assumed by Cahen, and argues for its existences through Geniza letters. He notes that if the term "antisemitism" could be used for the particular form of anti-Judaism understood from the Geniza letters, the antisemitism appears to have been local and sporadic rather than general and endemic. Leon Poliakov maintains that the term "antisemitism" is applicable to the hostility against Jews in pre-modern Islam "only with qualifications."

Jews in Islamic texts

|

And abasement and poverty were pitched upon them,

|

The Qur'an contains attacks on Jews for their refusal to recognize Muhammad as a prophet of God, and the Muslim holy text has defined Arab and Muslim attitudes towards Jews to this day, especially in the periods when Islamic fundamentalism was on the rise. Muhammad's attitude towards Jews was shaped by his failure to convert them to the religion he preached. During his life, Jews lived in the Arabian Peninsula, especially in and around Medina. They refused to accept Muhammad's teachings, and eventually he fought and defeated them, killing the majority of them.

The words "humility" and "humilitation" occur frequently in the Qur'an and later Muslim literature to describe the condition to which Jews must be reduced as a just punishment for their past rebelliousness -- the punishment that shows itself in the defeat they suffered at the hands of Christians and Muslims. The standard Quranic reference to Jews is verse 2:61,

Cowardice, greed, and chicanery are but a few of the characteristics that the Qur'an ascribes to the Jews. The Qur'an further associates Jews with interconfessional strife and rivalry (Qur'an ). It claims that Jews believe that they alone are beloved of God (Qur'an ) and that only they will achieve salvation.() According to the Qur'an, Jews blasphemously claim that Ezra is the son of God, as Christians claim Jesus is, (Qur'an ) and that God’s hand is fettered. (Qur'an ) Together with the pagans, Jews are “the most vehement of men in enmity to those who believe”. (Qur'an ) Some of those who are Jews "pervert words from their meanings", (Qur'an ) have committed wrongdoing, for which God has "forbidden some good things that were previously permitted them", (Qur'an ) they listen for the sake of mendacity,(Qur'an ) and some of them have committed usury and will receive "a painful doom." (Qur'an ) The Qur'an gives credence to the Christian claim of Jews scheming against Jesus, "...but God also schemed, and God is the best of schemers."(Qur'an ) In the Muslim view, the crucifixion of Jesus was an illusion, and thus the Jewish plots against him ended in complete failure. In numerous verses (3:63; 3:71; 4:46; 160-161; 5:41-44, 63-64, 82; 6:92) the Qur'an accuses Jews of deliberately obscuring and perverting scripture.

The traditional biographies of Muhammad recount the expulsion of the Jewish tribes of Banu Qaynuqa and Banu Nadir from Medina, the massacre of Banu Qurayza, and Muhammad's attack on the Jews of Khaybar. The rabbis of Medina are singled out as "men whose malice and enmity was aimed at the Apostle of God ". Jews appear in the biographies of Muhammad not only as malicious, but also deceitful, cowardly, and totally lacking in resolve. Their ignominy is presented in marked contrast to Muslim heroism, and in general conforms to the Quranic image of people with "wretchedness and baseness stamped upon them".(Qur'an 2:61)

The hadith continue the theme of Jewish hostility toward Muslims. One hadith says: "A Jew will not be found alone with a Muslim without plotting to kill him." According to another hadith, Muhammad said: "The Hour will not be established until you fight with the Jews, and the stone behind which a Jew will be hiding will say. "O Muslim! There is a Jew hiding behind me, so kill him.'"(Sahih Bukhari 4:52.177) This hadith has been quoted countless times, and has become part of the charter of Hamas.

Pre-modern times

The portrayal of the Jews in the early Islamic texts played a key role in shaping the attitudes towards them in the Muslim societies. According to Jane Gerber, "the Muslim is continually influenced by the theological threads of anti-Semitism embedded in the earliest chapters of Islamic history." In the light of the Jewish defeat at the hands of Muhammad, Muslims traditionally viewed Jews with contempt and as objects of ridicule. Jews were seen as hostile, cunning, and vindictive, but nevertheless weak and ineffectual. Cowardice was the quality most frequently attributed to Jews. Another stereotype associated with the Jews was their alleged propensity to trickery and deceit. While most anti-Jewish polemicists saw those qualities as inherently Jewish, ibn Khaldun attributed them to the mistreatment of Jews at the hands of the dominant nations. For that reason, says ibn Khaldun, Jews "are renowned, in every age and climate, for their wickedness and their slyness".

Some Muslim writers have inserted racial overtones in their anti-Jewish polemics. Al-Jahiz speaks of the deterioration of the Jewish stock due to excessive inbreeding. Ibn Hazm also implies racial qualities in his attacks on the Jews. However, these were exceptions, and the racial theme left little or no trace in the medieval Muslim anti-Jewish writings.

Islamic law demands that when under Muslim rule non-Muslims should be treated as dhimmis. Dhimmis were granted protection of life (including against other Muslim states), rights to reside in designated areas, worship, and work or trade. They were exempted from military service and Muslim religious duties, personal law, and some taxes. Certain conditions were imposed upon them, including paying the poll tax (jizyah) and land taxes as set by Muslim authorities. At the same time they were subject to various restrictions in relation to Muslims and Islam. Muslim men could marry dhimmi women and own dhimmi slaves, but the opposite was not true. They were forbidden to desecrate the Qur'an or defame Muhammad, and were forbidden to proselytize. Jews and other non-Muslims were at times subjected to a number of other restrictions such as limitations on dress, riding horses or camels, carrying arms, holding public office, building or repairing places of worship, mourning loudly, wearing shoes outside a Jewish ghetto, etc.

Anti-Jewish sentiments usually flared up at times of the Muslim political or military weakness or when Muslims felt that some Jews had overstepped the boundary of humilitation prescribed to them by the Islamic law. In Spain, ibn Hazm and Abu Ishaq focused their anti-Jewish writings on the latter allegation. This was also the chief motivation behind the massacres of Jews of Granada in 1066, when nearly 3,000 Jews were killed, and in Fez in 1033, when 6,000 Jews were killed. There were further massacres in Fez in 1276 and 1465.

Islamic law does not differentiate between Jews and Christians in their status as dhimmis. According to Bernard Lewis, the normal practice of Muslim governments until modern times was consistent with this aspect of sharia law. This view is countered by Jane Gerber, who maintains that of all dhimmis, Jews had the lowest status. Gerber maintains that this situation was especially pronounced in the latter centuries in the Ottoman Empire, where Christian communities enjoyed protection from the European countries, unavailable to the Jews. For example, in 18th-century Damascus, a Muslim noble held a festival, inviting to it all social classes in descending order, according to their social status: the Jews outranked only the peasants and prostitutes. In 1865, when the equality of all subjects of the Ottoman Empire was proclaimed, Cevdet Pasha, a high-ranking official observed: "whereas in former times, in the Ottoman State, the communities were ranked, with the Muslims first, then the Greeks, then the Armenians, then the Jews, now all of them were put on the same level. Some Greeks objected to this, saying: 'The government has put us together with the Jews. We were content with the supremacy of Islam.'"

According to Paul Johnson,

- "In theory, ... the status of Jewish dhimmi under Moslem rule was worse than under the Christians, since their right to practise their religion, and even their right to live, might be arbitrarily removed at any time. In practice, however, the Arab warriors ... had no wish to exterminate literate and industrious Jewish communities who provided them with reliable tax incomes and served them in innumerable ways. ... The Arab Moslems were slow to develop any religious animus against the Jews. In Moslem eyes, the Jews had sinned by rejecting Mohammed's claims, but they had not crucified him."

- "Always, in the background, there was the menace of anti-Semitism. It is described in the genizah documents by the word sinuth, hatred. ... Parts of Islam were much worse than others for Jews. Morocco was fanatical. So was northern Syria. ... Goitein concludes that the evidence does not support the view that in Egypt, at least, anti-Semitism was endemic or serious. But then Egypt under the Fatimids and Ayyubids was a refuge for persecuted Jews (and others) from all over the world."

Some scholars have questioned the correctness of the term "antisemitism" to Muslim culture in pre-modern times. Bernard Lewis distinguishes between "normal" prejudice against and "normal" persecution of different nations or beliefs on the one hand, and "antisemitism" on the nother hand. Lewis confines his definition of antisemitism to "the special and peculiar hatred of the Jews, which derives its unique power from the historical relationship between Judaism and Christianity, and the role assigned by Christians to the Jews in their writings and beliefs". From this premise Lewis concludes that until modern times "Arabs have not in fact been anti-Semitic as that word is used in the West... because for the most part they are not Christians." Claude Cahen argues that, while prejudice and hostility existed in the Islamic world, there was no antisemitism since there was scarcely any difference in the treatment accorded to Christians and Jews. Robert Chazan and Alan Davies argue that the most obvious difference between pre-modern Islam and pre-modern Christendom was the "rich melange of racial, ethic, and religious communities" in Islamic countries, within which "the Jews were by no means obvious as lone dissenters, as they had been earlier in the world of polytheism or subsequently in most of medieval Christendom." According to Chazan and Davies, this lack of uniqueness ameliorated the circumstances of Jews in the medieval world of Islam.

Disputing this view, Shelomo Dov Goitein argues that the existence of antisemitism in pre-modern Islam is supported by documentary evidence: "he Genizah material confirms the existence of a discernible form of anti-Judaism in the time and the place considered here, but that form of 'anti-Semitism', if we may use this term, appears to have been local and sporadic rather than general and endemic." Leon Poliakov maintains that the term "antisemitism" is applicable to the hostility against Jews in pre-modern Islam "only with qualifications".

Modern period

19th century

Historian Martin Gilbert writes that it was in the 19th century that the position of Jews worsened in Muslim countries.

There was a massacre of Jews in Baghdad in 1828. In 1839, in the eastern Persian city of Meshed, a mob burst into the Jewish Quarter, burned the synagogue, and destroyed the Torah scrolls. It was only by forcible conversion that a massacre was averted. There was another massacre in Barfurush in 1867.

In 1840, the Jews of Damascus were falsely accused of having murdered a Christian monk and his Muslim servant and of having used their blood to bake Passover bread. A Jewish barber was tortured until he "confessed"; two other Jews who were arrested died under torture, while a third converted to Islam to save his life. Throughout the 1860s, the Jews of Libya were subjected to what Gilbert calls punitive taxation. In 1864, around 500 Jews were killed in Marrakech and Fez in Morroco. In 1869, 18 Jews were killed in Tunis, and an Arab mob looted Jewish homes and stores, and burned synagogues, on Jerba Island. In 1875, 20 Jews were killed by a mob in Demnat, Morocco; elsewhere in Morocco, Jews were attacked and killed in the streets in broad daylight. In 1891, the leading Muslims in Jerusalem asked the Ottoman authorities in Constantinople to prohibit the entry of Jews arriving from Russia. In 1897, synagogues were ransacked and Jews were murdered in Tripolitania.

Benny Morris writes that one symbol of Jewish degradation was the phenomenon of stone-throwing at Jews by Muslim children. Morris quotes a 19th century traveler: "I have seen a little fellow of six years old, with a troop of fat toddlers of only three and four, teaching to throw stones at a Jew, and one little urchin would, with the greatest coolness, waddle up to the man and literally spit upon his Jewish gaberdine. To all this the Jew is obliged to submit; it would be more than his life was worth to offer to strike a Mahommedan."

20th century

See also: Jewish exodus from Arab landsThe massacres of Jews in Muslim countries continued into the 20th century. Martin Gilbert writes that 40 Jews were murdered in Taza, Morocco in 1903. In 1905, old laws were revived in Yemen forbidding Jews from raising their voices in front of Muslims, building their houses higher than Muslims, or engaging in any traditional Muslim trade or occupation. The Jewish quarter in Fez was almost destroyed by a Muslim mob in 1912.

There were Nazi-inspired pogroms in Algeria in the 1930s, and massive attacks on the Jews in Iraq and Libya in the 1940s (see Farhud). Pro-Nazi Muslims slaughtered dozens of Jews in Baghdad in 1941.

George Gruen attributes the increased animosity towards Jews in the Arab world to several factors, including the breakdown of the Ottoman Empire and traditional Islamic society; domination by Western colonial powers under which Jews gained a disproportionatly larger role in the commercial, professional, and administrative life of the region; the rise of Arab nationalism, whose proponents sought the wealth and positions of local Jews through government channels; resentment over Jewish nationalism and the Zionist movement; and the readiness of unpopular regimes to scapegoat local Jews for political purposes.

Antagonism and violence increased still further as resentment against Zionist efforts in the British Mandate of Palestine spread. Anti-Zionist propaganda in the Middle East frequently adopts the terminology and symbols of the Holocaust to demonize Israel and its leaders. At the same time, Holocaust denial and Holocaust minimization efforts have found increasingly overt acceptance as sanctioned historical discourse in a number of Middle Eastern countries. Arabic- and Turkish-edition of Hitler's Mein Kampf and The Protocols of the Elders of Zion have found an audience in the region with limited critical response by local intellectuals and media. See International Conference to Review the Global Vision of the Holocaust.

According to Robert Satloff, Muslims and Arabs were involved both as rescuers and perpetrators of the Holocaust during Italian and German Nazi occupation of Morocco, Tunisia and Libya.

Racial antisemitism

Main article: Racial antisemitismRacial antisemitism replaced the hatred of Judaism with the hatred of Jews as a group. In the context of the Industrial Revolution, following the emancipation of the Jews, Jews rapidly urbanized and experienced a period of greater social mobility. With the decreasing role of religion in public life tempering religious antisemitism, a combination of growing nationalism, the rise of eugenics, and resentment at the socio-economic success of the Jews led to the newer, and more virulent, racist antisemitism.

New antisemitism

Main article: New antisemitismIn recent years some scholars of history, psychology, religion, and representatives of Jewish groups, have noted what they describe as the new antisemitism, which they often associate with the Left rather than the Right, and argue that the language of anti-Zionism and criticism of Israel are used to attack the Jews more broadly.

Antisemitism and anti-Zionism

Some commentators believe that criticisms of Israel and Zionism are often disproportionate in degree and unique in kind, and attribute this to antisemitism. Some supporters of Zionism go so far as to say that all expressions of anti-Zionism qualify as antisemitism. Critics of this view believe that associating anti-Zionism with antisemitism is intended to stifle debate, deflect attention from valid criticisms, and taint anyone opposed to Israeli actions and policies.

Since the support and defense of Israel has become a central focus of Jewish life for many since 1948, many Jews see attacks on the existence of Israel as inherently antisemitic. For example, Yehuda Bauer, Professor of Holocaust Studies at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, has argued: "If you advocate the abolition of Israel ... that means in fact that you're against the people who live there. If you are, for example, against the existence of Malaysia, you are anti-Malay. If you are against the existence of Israel, you are anti-Jewish."

According to Tanya Reinhardt, Professor of Linguistics at Tel Aviv University who said she was speaking as one who loves the country and its people, "Being against Israel is the best act of solidarity and compassion with the Jews that one can have. ... The system of prisons that Israel is building is also a prison for Israelis. This small state is making itself the enemy of the entire Arab world and now the Muslim world. A state with this strategy does not have a future, so the solution for the Palestinians is also the solution for Israel."

Another position is that criticism of Israel or Zionism is not in itself antisemitic, but that anti-Zionism can be used to hide antisemitism. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., in response to a question from the audience after a lecture at Harvard University shortly before his death in 1968, said:

- "When people criticize Zionists they mean Jews; you are talking anti-Semitism."

On April 3, 2006, the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights announced that anti-Israelism or anti-Zionism may often serve as "camouflage" for "anti-Semitic bigotry" on American college campuses:

On many campuses, anti-Israeli or anti-Zionist propaganda has been disseminated that includes traditional anti-Semitic elements, including age-old anti-Jewish stereotypes and defamation. This has included, for example, anti-Israel literature that perpetuates the medieval anti-Semitic blood libel of Jews slaughtering children for ritual purpose, as well as anti-Zionist propaganda that exploits ancient stereotypes of Jews as greedy, aggressive, overly powerful, or conspiratorial. Such propaganda should be distinguished from legitimate discourse regarding foreign policy. Anti-Semitic bigotry is no less morally deplorable when camouflaged as anti-Israelism or anti-Zionism.

One of the first people who criticized Israel immediately after its Independence was Albert Einstein who co-authored a letter to the editor of the New York Times criticizing it for the massacres at Deir Yassin. Einstein, Albert (1948-12-04). "New Palestine Party Visit of Menachen Begin and Aims of Political Movement Discussed". New York Times. {{cite news}}: Check date values in: |date= (help); Unknown parameter |coauthors= ignored (|author= suggested) (help)

Thomas Friedman wrote that "riticizing Israel is not anti-Semitic, and saying so is vile. But singling out Israel for opprobrium and international sanction - out of proportion to any other party in the Middle East - is anti-Semitic, and not saying so is dishonest".

In 2005, the European Monitoring Centre on Racism and Xenophobia (EUMC), part of the European Union, tried to define more clearly the relationship between anti-Zionism and anti-Semitism. The EUMC developed a working definition of anti-Semitism that defined ways in which attacking Israel or Zionism could be anti-Semitic. The definition states:

Examples of the ways in which anti-Semitism manifests itself with regard to the State of Israel taking into account the overall context could include:

- Denying the Jewish people right to self-determination, e.g. by claiming that the existence of a state of Israel is a racist endeavor.

- Applying double standards by requiring of it a behavior not expected or demanded of any other democratic nation.

- Using the symbols and images associated with classic anti-Semitism (e.g. claims of Jews killing Jesus or blood libel) to characterize Israel or Israelis.

- Drawing comparisons of contemporary Israeli policy to that of the Nazis.

- Holding Jews collectively responsible for actions of the State of Israel. However, criticism of Israel similar to that leveled against any other country cannot be regarded as anti-Semitic.

An academic survey of attitudes towards Jewish people and Israel was recently conducted among 5,000 participants in ten European countries. Kaplan and Small of Yale University published the results in the Journal of Conflict Resolution. They found an almost perfect correlation between anti-Zionist attitudes and frank anti-Semitism. People who believed that the Israeli soldiers "intentionally target Palestinian civilians," and that "Palestinian suicide bombers who target Israeli civilians" are justified, also believed that "Jews don't care what happens to anyone but their own kind," "Jews have a lot of irritating faults," and "Jews are more willing than others to use shady practices to get what they want." Diana Muir, summarizing the article, states that "only a small fraction of Europeans believe any of these things." She further claims that "anti-Semitism and anti-Zionism flourish among the few, but those few are over-represented in Europe's newspapers, its universities, and its left-wing political parties."

European Commission definition

The European Commission on Racism and Intolerance has proposed a Working Definition of Antisemitism outlining some of the ways in which anti-Zionism may cross the line into antisemitism. "Examples of the ways in which antisemitism manifests itself with regard to the State of Israel taking into account the overall context could include:

- denying the Jewish people right to self-determination, e.g. by claiming that the existence of a state of Israel is a racist endeavor;

- applying double standards by requiring of it a behavior not expected or demanded of any other democratic nation;

- using the symbols and images associated with classic antisemitism (e.g. claims of Jews killing Jesus or blood libel) to characterize Israel or Israelis; and

- holding Jews collectively responsible for the actions of the State of Israel."

Bans on kosher slaughter

The kosher slaughter of animals is currently banned in Norway, Switzerland and Sweden, and partially banned in Holland (for older animals only, who are considered to take longer to lose consciousness). The Swiss banned kosher slaughter in 1902 and saw an antisemitic backlash against a proposal to lift the ban a century later. Both Holland and Switzerland have considered extending the ban in order to prohibit importing kosher products. The former chief rabbi of Norway, Michael Melchior, argues that antisemitism is a motive for the bans: "I won't say this is the only motivation, but it's certainly no coincidence that one of the first things Nazi Germany forbade was kosher slaughter. I also know that during the original debate on this issue in Norway, where shechitah has been banned since 1930, one of the parliamentarians said straight out, 'If they don't like it, let them go live somewhere else.'"

Antisemitism and specific countries

United States

- Further information: ]

Jews were often condemned by populist politicians alternately for their left-wing politics, or their perceived wealth, at the turn of the century. Antisemitism grew in the years leading up to America's entry into World War II, Father Charles Coughlin, a radio preacher, as well as many other prominent public figures, condemned "the Jews," and Henry Ford reprinted The Protocols of the Elders of Zion in his newspaper.

In 1939 a Roper poll found that only thirty-nine percent of Americans felt that Jews should be treated like other people. Fifty-three percent believed that "Jews are different and should be restricted" and ten percent believed that Jews should be deported. Several surveys taken from 1940 to 1946 found that Jews were seen as a greater threat to the welfare of the United States than any other national, religious, or racial group. It has been estimated that 190,000 - 200,000 Jews could have been saved during the Second World War had it not been for bureaucratic obstacles to immigration deliberately created by Breckinridge Long and others.

In a speech at an America First rally on September 11 1941 in Des Moines, Iowa entitled "Who Are the War Agitators?", Charles Lindbergh claimed that three groups had been "pressing this country toward war": the Roosevelt Administration, the British, and the Jews - and complained about what he insisted was the Jews' "large ownership and influence in our motion pictures, our press, our radio and our government." The antisemitism of Lindbergh is one of the subjects of the novel The Plot Against America (2004) by Philip Roth.

Unofficial antisemitism was also widespread in the first half of the century. For example, to limit the growing number of Jewish students between 1919-1950s a number of private liberal arts universities and medical and dental schools employed Numerus clausus. These included Harvard University, Columbia University, Cornell University, and Boston University. In 1925 Yale University, which already had such admissions preferences as "character", "solidity", and "physical characteristics" added a program of legacy preference admission spots for children of Yale alumni, in an explicit attempt to put the brakes on the rising percentage of Jews in the student body. This was soon copied by other Ivy League and other schools, and admissions of Jews were kept down to 10% through the 1950s. Such policies were for the most part discarded during the early 1960s.

Some cults also support conspiracy theories regarding Jews as dominating and taking over the world. These cults are often vitriolic and severely antisemititic. For instance, the Necedah Shrine Cult from the 1950s on to the mid 1980's, has Mary Ann Van Hoof receiving antisemitic "visions" from the Virgin Mary telling her that the Rothschilds, a prominent Jewish banking family, are "mongrel yids(Jews)" bent on dominating the entire world economy through international banking. Most of the worlds problems, from poverty to world wars, are the cause of International Banking Jews and their "satanic secret society," according to Van Hoof.

American antisemitism underwent a modest revival in the late twentieth century. The Nation of Islam under Louis Farrakhan claimed that Jews were responsible for slavery, economic exploitation of black labor, selling alcohol and drugs in their communities, and unfair domination of the economy. Jesse Jackson issued his infamous "Hymietown" remarks during the 1984 Presidential primary campaign.

According to ADL surveys begun in 1964, African-Americans are "significantly more likely" than white Americans to hold antisemitic beliefs, although there is a strong correlation between education level and the rejection of antisemitic stereotypes.

Europe

The summary of a 2004 poll by the "Pew Global Attitudes Project" noted, "Despite concerns about rising antisemitism in Europe, there are no indications that anti-Jewish sentiment has increased over the past decade. Favorable ratings of Jews are actually higher now in France, Germany and Russia than they were in 1991. Nonetheless, Jews are better liked in the U.S. than in Germany and Russia."

However, according to 2005 survey results by the ADL, antisemitic attitudes remain common in Europe. Over 30% of those surveyed indicated that Jews have too much power in business, with responses ranging from lows of 11% in Denmark and 14% in England to highs of 66% in Hungary, and over 40% in Poland and Spain. The results of religious antisemitism also linger and over 20% of European respondents agreed that Jews were responsible for the death of Jesus, with France having the lowest percentage at 13% and Poland having the highest number of those agreeing, at 39%.

The Vienna-based European Union Monitoring Centre (EUMC), for 2002 and 2003, identified France, Germany, the United Kingdom, Belgium, and the Netherlands as EU member countries with notable increases in incidents. Many of these incidents can be linked to immigrant communities in these countries and result from hightened tensions in the Middle East. As these nations keep reliable and comprehensive statistics on antisemitic acts, and are engaged in combating antisemitism, their data was readily available to the EUMC.

In western Europe, traditional far-right groups still account for a significant proportion of the attacks against Jews and Jewish properties; disadvantaged and disaffected Muslim youths increasingly were responsible for most of the other incidents. In Eastern Europe, with a much smaller Muslim population, neo-Nazis and others members of the radical political fringe were responsible for most antisemitic incidents. Antisemitism remained a serious problem in Russia and Belarus, and elsewhere in the former Soviet Union, with most incidents carried out by ultra-nationalist and other far-right elements. The stereotype of Jews as manipulators of the global economy continues to provide fertile ground for antisemitic aggression.

Denmark

Anti-semitism in Denmark has not been as widespread as in other countries. Initially Jews were banned as in other countries in Europe, but beginning in the 17th century, Jews were allowed to live in Denmark freely, unlike in other European countries where they were forced to live in ghettos.

In 1819 a series of anti-Jewish riots in Germany spread to several neighboring countries including Denmark, resulting in mob attacks on Jews in Copenhagen and many provincial towns. These riots were known as Hep! Hep! Riots, from the derogatory rallying cry against the Jews in Germany. Riots lasted for five months during which time shop windows were smashed, stores looted, homes attacked, and Jews physically abused.

However, during World War II, Denmark was very uncooperative with the Nazi occupation on Jewish matters. Danish officials repeatedly insisted to the German occupation authorities that there was no "Jewish problem" in Denmark. As a result, even ideologically committed Nazis such as Reich Commissioner Werner Best followed a strategy of avoiding and deferring discussion of Denmark's Jews. When Denmark's German occupiers began planning the deportation of the 8,000 or so Jews in Denmark to Nazi concentration camps, many Danes and Swedes took part in a collective effort to evacuate the roughly 8,000 Jews of Denmark by sea to nearby Sweden (see also Rescue of the Danish Jews).

Today, Denmark has one of the lowest rates of anti-semitism in Europe, at only 11%.

France

Antisemitism was particularly virulent in Vichy France during WWII. The Vichy government openly collaborated with the Nazi occupiers to identify Jews for deportation and transportation to the death camps.

Today, despite a steady trend of decreasing antisemitism among the indigenous population, acts of antisemitism are a serious cause for concern, as is tension between the Jewish and Muslim populations of France, both the largest in Europe. However, according to a poll by the Pew Global Attitudes Project, 71% of French Muslims had positive views of Jews, the highest percentage in the world. According to the National Advisory Committee on Human Rights, antisemitic acts account for a majority — 72% in all in 2003 — of racist acts in France.

In July 2005, the Pew Global Attitudes Project found that 82% of French people questioned had favorable attitudes towards Jews, the second highest percentage of the countries questioned. The Netherlands was highest at 85%.

Holocaust denial and antisemitic speech are prohibited under the 1990 Gayssot Act.

Germany

From the early Middle Ages to the 18th century, the Jews in Germany were subject to many persecutions as well as brief times of tolerance. Though the 19th century began with a series of riots and pogroms against the Jews, emancipation followed in 1848, so that, by the early 20th century, the Jews of Germany were the most integrated in Europe. The situation changed in the early 1930's with the rise of the Nazis and their explicitly antisemitic program. Hate speech which referred to Jewish citizens as "dirty Jews" became common in antisemitic pamphlets, newspapers such as the Völkischer Beobachter and Der Stürmer, and radio. Additionally, blame was laid on German Jews for having caused Germany's defeat in World War I (see Dolchstosslegende).

Anti-Jewish propaganda expanded rapidly. Nazi cartoons depicting "dirty Jews" frequently portrayed a dirty, physically unattractive and badly dressed "talmudic" Jew in traditional religious garments similar to those worn by Hasidic Jews. Articles attacking Jewish Germans, while concentrating on commercial and political activities of prominent Jewish individuals, also frequently attacked them based on religious dogmas, such as blood libel.

The Nazi antisemitic program quickly expanded beyond mere speech. Starting in 1933, repressive laws were passed against Jews, culminating in the Nuremberg Laws which removed most of the rights of citizenship from Jews, using a racial definition based on descent, rather than any religious definition of who was a Jew. Sporadic violence against the Jews became widespread with the Kristallnacht riots, which targeted Jewish homes, businesses and synagogues, killing hundreds across Germany and Austria.

The antisemitic agenda culminated in the genocide of the Jews of Europe, known as the Holocaust.

Hungary

In June 1944, Hungarian police deported nearly 440,000 Jews in more than 145 trains, mostly to Auschwitz . Ultimately, over 400,000 Jews in Hungary were killed during the Holocaust. Although Jews were on both sides of the Hungarian Revolution of 1956, there was a perceptible antisemitic backlash against Jewish members of the former government led by Mátyás Rákosi.

Today, hatred towards Judaism and Israel can be observed from many prominent Hungarian politicians. The most famous example is the MIÉP party and its Chairman, István Csurka.

Antisemitism in Hungary was manifested mainly in far right publications and demonstrations. MIÉP supporters continued their tradition of shouting antisemitic slogans and tearing the US flag to shreds at their annual rallies in Budapest in March 2003 and 2004, commemorating the 1848–49 revolution. Further, during the anniversary demonstrations of both right and left marking the 1956 uprising, antisemitic and anti-Israel slogans were heard from the right, such as accusing Israel of war crimes. The center-right traditionally keeps its distance from the right-wing demonstration, which was led by Csurka.

Norway

See also Jews in Norway

Jews were prohibited from living or entering Norway by paragraph 2 of the Constitution, which originally read, "The evangelical-Lutheran religion remains the public religion of the State. Those inhabitants, who confess thereto, are bound to raise their children to the same. Jesuits and monkish orders are not permitted. Jews are still prohibited from entry to the Realm." In 1851 the last sentence was struck. Monks were permitted in 1897; Jesuits not before 1956.

Poland

Further information: History of the Jews in PolandIn 1264, Duke Boleslaus the Pious from Greater Poland legislated a Statute of Kalisz, a charter for Jewish residence and protection, which encouraged money-lending, hoping that Jewish settlement would contribute to the development of the Polish economy. By the sixteenth century, Poland had become the center of European Jewry and the most tolerant of all European countries regarding the matters of faith, although occasionally also Poland witnessed violent antisemitic incidents.

At the onset of the seventeenth century, however, the tolerance began to give way to increased antisemitism. Elected to the Polish throne King Sigismund III of the Swedish House of Vasa, a strong supporter of the counter-reformation, began to undermine the principles of the Warsaw Confederation and the religious tolerance in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, revoking and limiting privileges of all non-Catholic faiths. In 1628 he banned publication of Hebrew books, including the Talmud. Acclaimed twentieth century historian Simon Dubnow, in his magnum opus History of the Jews in Poland and Russia, detailed:

- "At the end of the 16th century and thereafter, not one year passed without a blood libel trial against Jews in Poland, trials which always ended with the execution of Jewish victims in a heinous manner..." (ibid., volume 6, chapter 4).