Page version status

The latest pending revision is displayed on this page

Family of sharks

| Hammerhead sharks Temporal range: Paleocene to present PreꞒ Ꞓ O S D C P T J K Pg N | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scalloped hammerhead | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Chondrichthyes |

| Subclass: | Elasmobranchii |

| Order: | Carcharhiniformes |

| Suborder: | Carcharhinoidei |

| Family: | Sphyrnidae T. N. Gill, 1872 |

| Genera | |

| |

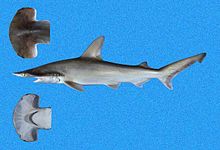

The hammerhead sharks are a group of sharks that form the family Sphyrnidae, so named for the unusual and distinctive structure of their heads, which are flattened and laterally extended into a "hammer" shape called a cephalofoil. Most hammerhead species are placed in the genus Sphyrna, while the winghead shark is placed in its own genus, Eusphyra. Many, but not necessarily mutually exclusive, functions have been postulated for the cephalofoil, including sensory reception, manoeuvering, and prey manipulation. The cephalofoil gives the shark superior binocular vision and depth perception.

Hammerheads are found worldwide in warmer waters along coastlines and continental shelves. Unlike most sharks, some hammerhead species usually swim in schools during the day, becoming solitary hunters at night. Some of these schools can be found near Malpelo Island in Colombia, the Galápagos Islands in Ecuador, Cocos Island off Costa Rica, near Molokai in Hawaii, and off southern and eastern Africa.

Description

The known species range from 0.9 to 6.0 m (2 ft 11 in to 19 ft 8 in) in length and weigh from 3 to 580 kg (6.6 to 1,278.7 lb). They are usually light gray and have a greenish tint. Their bellies are white, which allows them to blend into the background when viewed from below, and sneak up on their prey. Their heads have lateral projections that give them a hammer-like shape. While overall similar, this shape differs somewhat between species; e.g., a distinct T-shape in the great hammerhead, a rounded head with a central notch in the scalloped hammerhead, and an unnotched rounded head in the smooth hammerhead.

Hammerheads have disproportionately small mouths compared to other shark species. They are also known to form schools during the day, sometimes in groups over 100. In the evening, like other sharks, they become solitary hunters. National Geographic explains that hammerheads can be found in warm, tropical waters, but during the summer, they participate in a mass migration to search for cooler waters.

Taxonomy and evolution

Since sharks do not have mineralized bones and rarely fossilize, only their teeth are commonly found as fossils. The hammerheads seem closely related to the carcharhinid sharks that evolved during the mid-Tertiary period. According to DNA studies, the ancestor of the hammerheads probably lived in the Miocene epoch about 20 million years ago.

Using mitochondrial DNA, a phylogenetic tree of the hammerhead sharks showed the winghead shark as its most basal member. As the winghead shark has proportionately the largest "hammer" of the hammerhead sharks, this suggests that the first ancestral hammerhead sharks also had large hammers. Fossils show that hammerheads might have evolved earlier during the Paleocene.

Cephalofoil

The hammer-like shape of the head may have evolved at least in part to enhance the animal's vision. The positioning of the eyes, mounted on the sides of the shark's distinctive hammer head, allows 360° of vision in the vertical plane, meaning the animals can see above and below them at all times. They also have an increased binocular vision and depth of visual field as a result of the cephalofoil. The shape of the head was previously thought to help the shark find food, aiding in close-quarters maneuverability, and allowing sharp turning movement without losing stability. The unusual structure of its vertebrae, though, has been found to be instrumental in making the turns correctly, more often than the shape of its head, though it would also shift and provide lift. From what is known about the winghead shark, the shape of the hammerhead apparently has to do with an evolved sensory function. Like all sharks, hammerheads have electroreceptory sensory pores called ampullae of Lorenzini. The pores on the shark's head lead to sensory tubes, which detect electric fields generated by other living creatures. By distributing the receptors over a wider area, like a larger radio antenna, hammerheads can sweep for prey more effectively.

Reproduction

Reproduction occurs only once a year for hammerhead sharks, and usually occurs with the male shark biting the female shark violently until she agrees to mate with him. The hammerhead sharks exhibit a viviparous mode of reproduction with females giving birth to live young. Like other sharks, fertilization is internal, with the male transferring sperm to the female through one of two intromittent organs called claspers. The developing embryos are at first sustained by a yolk sac. When the supply of yolk is exhausted, the depleted yolk sac transforms into a structure analogous to a mammalian placenta (called a "yolk sac placenta" or "pseudoplacenta"), through which the mother delivers sustenance until birth. Once the baby sharks are born, they are not taken care of by the parents in any way. Usually, a litter consists of 12 to 15 pups, except for the great hammerhead, which gives birth to litters of 20 to 40 pups. These baby sharks huddle together and swim toward warmer water until they are old enough and large enough to survive on their own.

In 2007, the bonnethead shark was found to be capable of asexual reproduction via automictic parthenogenesis, in which a female's ovum fuses with a polar body to form a zygote without the need for a male. This was the first shark known to do this.

Diet

Hammerhead sharks eat a large range of prey such as fish (including other sharks), squid, octopus, and crustaceans. Stingrays are a particular favorite. These sharks are often found swimming along the bottom of the ocean, stalking their prey. Their unique heads are used as a weapon when hunting down prey. The hammerhead shark uses its head to pin down stingrays and eats the ray when the ray is weak and in shock. The great hammerhead, tending to be larger and more aggressive than most hammerheads, occasionally engages in cannibalism, eating other hammerhead sharks, including its own young. In addition to the typical animal prey, bonnetheads have been found to feed on seagrass, which sometimes makes up as much as half their stomach contents. They may swallow it unintentionally, but they are able to partially digest it. This is the only known case of a potentially omnivorous species of shark.

Species

| Species | Common names | IUCN Red List status | Population trend | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Eusphyra blochii | Winghead shark | Endangered | Decreasing | |

|

Sphyrna corona | Scalloped bonnethead | Critically Endangered | Unknown | |

| Sphyrna gilberti | Carolina hammerhead | Yet to be assessed | Unknown | ||

|

Sphyrna lewini | Scalloped hammerhead | Critically Endangered | Decreasing | |

|

Sphyrna media | Scoophead | Data deficient | Unknown | |

|

Sphyrna mokarran | Great hammerhead | Critically Endangered | Decreasing | |

|

Sphyrna tiburo | Bonnethead | Endangered | Decreasing | |

|

Sphyrna tudes | Smalleye hammerhead | Vulnerable | Decreasing | |

|

Sphyrna zygaena | Smooth hammerhead | Vulnerable | Decreasing |

Relationship with humans

According to the International Shark Attack File, humans have been subjects of 17 documented, unprovoked attacks by hammerhead sharks within the genus Sphyrna since 1580 AD. No human fatalities have been recorded.

The great and the scalloped hammerheads are listed on the World Conservation Union's (IUCN) 2008 Red List as endangered, whereas the smalleye hammerhead is listed as vulnerable. The status given to these sharks is as a result of overfishing and demand for their fins, an expensive delicacy. Among others, scientists expressed their concern about the plight of the scalloped hammerhead at the American Association for the Advancement of Science annual meeting in Boston. The young swim mostly in shallow waters along shores all over the world to avoid predators.

Shark fins are prized as a delicacy in certain countries in Asia (such as China), and overfishing is putting many hammerhead sharks at risk of extinction. Fishermen who harvest the animals typically cut off the fins and toss the remainder of the fish, which is often still alive, back into the sea. This practice, known as finning, is lethal to the shark.

In native Hawaiian culture, sharks are considered to be gods of the sea, protectors of humans, and cleaners of excessive ocean life. Some of these sharks are believed to be family members who died and have been reincarnated into shark form, but others are considered man-eaters, also known as niuhi. These sharks include great white sharks, tiger sharks, and bull sharks. The hammerhead shark, also known as mano kihikihi, is not considered a man-eater or niuhi; it is considered to be one of the most respected sharks of the ocean, an aumakua. Many Hawaiian families believe that they have an aumakua watching over them and protecting them from the niuhi. The hammerhead shark is thought to be the birth animal of some children. Hawaiian children who are born with the hammerhead shark as an animal sign are believed to be warriors and are meant to sail the oceans. Hammerhead sharks rarely pass through the waters of Maui, but many Maui natives believe that their swimming by is a sign that the gods are watching over the families, and the oceans are clean and balanced.

In captivity

The relatively small bonnethead is regular at public aquariums, as it has proven easier to keep in captivity than the larger hammerhead species, and it has been bred at a handful of facilities. Nevertheless, at up to 1.5 m (5 ft) in length and with highly specialized requirements, very few private aquarists have the experience and resources necessary to maintain a bonnethead in captivity. The larger hammerhead species can reach more than twice that size and are considered difficult, even compared to most other similar-sized sharks (such as Carcharhinus species, lemon shark, and sand tiger shark) regularly kept by public aquariums. They are particularly vulnerable during transport between facilities, may rub on surfaces in tanks, and may collide with rocks, causing injuries to their heads, so they require very large, specially adapted tanks. As a consequence, relatively few public aquaria have kept them for long periods. The scalloped hammerhead is the most frequently maintained large species, and it has been kept long term at public aquaria in most continents, but primarily in North America, Europe, and Asia. In 2014, fewer than 15 public aquaria in the world kept scalloped hammerheads. Great hammerheads have been kept at a few facilities in North America, including Atlantis Paradise Island Resort (Bahamas), Adventure Aquarium (New Jersey), Georgia Aquarium (Atlanta), Mote Marine Laboratory (Florida), and the Shark Reef at Mandalay Bay (Las Vegas). Smooth hammerheads have also been kept in the past.

Protection

In March 2013, three endangered, commercially valuable sharks, the hammerheads, the oceanic whitetip, and porbeagle, were added to Appendix II of CITES, bringing shark fishing and commerce of these species under licensing and regulation.

Cultural significance

Among Torres Strait Islanders, the hammerhead shark, known as the beizam, is a common family totem and often represented in cultural artefacts such as the elaborate headdresses worn for ceremonial dances, known as dhari or dari. They are associated with law and order. Renowned artist Ken Thaiday Snr is known for his representations of beizam in his sculptural dari and other works.

See also

For a topical guide, see Outline of sharks.References

- ^ Fossilworks Database. "Fossilworks Paleotology database". Fossilworks. John Alroy. Retrieved 24 April 2018.

- ^ Barley, Shanta (26 February 2019). "Why the hammerhead shark got its hammer". New Scientist. Retrieved 3 March 2021.

- Hessing, S. (2000). Sphyrna tiburo. Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved on 2012-12-19.

- "Record Hammerhead Pregnant With 55 Pups". Discovery News. Associated Press. 1 July 2006. Archived from the original on 22 June 2011. Retrieved 18 October 2008.

- Hammerhead Shark. Sharks-world.com. Retrieved on 2012-12-19.

- "Marine Species ID: Great Hammerhead vs. Scalloped and Smooth Hammerhead". Sport Diver. Retrieved 7 October 2020.

- "Hammerhead Shark". NationalGeographic.com. 10 September 2010. Retrieved 9 November 2016.

- "Hammerhead shark study shows cascade of evolution affected size, head shape". ScienceDaily.com. University of Colorado at Boulder. 19 May 2010. Retrieved 9 November 2016.

- Martin, R. Aidan. "Origin and Evolution of the 'Hammer'". elasmo-research.org. Retrieved 31 January 2005.

- McComb, D. M.; Tricas, T. C.; Kajiura, S. M. (2009). "Enhanced visual fields in hammerhead sharks". Journal of Experimental Biology. 212 (24): 4010–8. doi:10.1242/jeb.032615. PMID 19946079.

- McComb, D. Michelle; et al. (27 November 2009). "Hammerhead shark mystery solved". BBC News. Retrieved 4 May 2010.

- "World's Deadliest: Hammerhead Sharks". video.nationalgeographic.com. Retrieved 23 May 2015.

- Otfinoski, Steven (2000). Hammerheads and Other Sharks. World Book, Inc. pp. 16. ISBN 978-0716612100.

- Martin, R. Aidan (August 1993). "If I Had a Hammer". Rodale's Scuba Diving. Retrieved 31 March 2006.

- ^ Hammerhead Shark. Aquatic Community. Retrieved on 2012-12-19.

- Chapman, DD; Shivji, MS; Louis, E; Sommer, J; Fletcher, H; Prodöhl, PA (22 August 2007). "Virgin birth in a hammerhead shark". Biology Letters. 3 (4): 425–7. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2007.0189. PMC 2390672. PMID 17519185.

- "Great hammerhead shark". EnchantedLearning.com. Enchanted Learning Software. Retrieved 19 December 2012.

- Hannah Lang (29 June 2017). "This Shark Eats Grass, and No One Knows Why". National Geographic.

- University), Colin Simpfendorfer (James Cook; Jonathan Smart (James Cook University, Queensland (18 February 2015). "IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: Eusphyra blochii". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Retrieved 19 August 2020.

- Seahorse), Riley Pollom (Project; Mario Espinoza (James Cook University, Queensland; Education), Oscar Sosa-Nishizaki (The Ensenada Center for Scientific Research and Higher; Katelyn Herman (Georgia Aquarium, Atlanta; Foundation), Andrés F. Navia (Squalus; Society)), Paola A. Mejía-Falla (Squalus Foundation (Wildlife Conservation; Bizzarro, Joe; Burgos-Vázquez, Itzigueri; Jiménez, Juan Carlos Pérez (7 February 2019). "IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: Sphyrna corona". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Retrieved 31 May 2021.

- "Catalogue of Life: Sphyrna gilberti Quattro, Driggers III, Grady, Ulrich & Roberts, 2013". catalogueoflife.org. Retrieved 30 August 2015.

- Pacoureau, Nathan; Sherley, Richard; Liu, Kwang-Ming; Sul (CEPSUL/ICMBio)), Rodrigo Barreto (Centro de Pesquisa e Conservação da Biodiversidade Marinha do Sudeste e; Katelyn Herman (Georgia Aquarium, Atlanta; Fernando, Daniel; Romanov, Evgeny; Nicholas Dulvy (Simon Fraser University, Canada / IUCN SSC Shark Specialist Group); Cassandra Rigby (James Cook University, Queensland (8 November 2018). "IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: Sphyrna lewini". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Retrieved 19 August 2020.

- Casper, B.M. & Burgess, G.H. (2006). Sphyrna media. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2006.RLTS.T60201A12317805.en

- Pacoureau, Nathan; Sherley, Richard; Liu, Kwang-Ming; Sul (CEPSUL/ICMBio)), Rodrigo Barreto (Centro de Pesquisa e Conservação da Biodiversidade Marinha do Sudeste e; Katelyn Herman (Georgia Aquarium, Atlanta; Fernando, Daniel; Romanov, Evgeny; Cassandra Rigby (James Cook University, Queensland; Henning Winker (aSouth African National Biodiversity Institute, Kirstenbosch (9 November 2018). "IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: Sphyrna mokarran". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Retrieved 19 August 2020.

- Pollom, R.; Carlson, J.; Charvet, P.; Avalos, C.; Bizzarro, J.; Blanco-Parra, MP, Briones Bell-lloch, A.; Burgos-Vázquez, M.I.; Cardenosa, D.; Cevallos, A.; Derrick, D.; Espinoza, E.; Espinoza, M.; Mejía-Falla, P.A.; Navia, A.F.; Pacoureau, N.; Pérez Jiménez, J.C.; Sosa-Nishizaki, O. (2020). "Sphyrna tiburo". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020: e.T39387A124409680. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-3.RLTS.T39387A124409680.en. Retrieved 3 March 2021.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Mycock, S. G. (31 January 2006). "IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: Sphyrna tudes". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Retrieved 19 August 2020.

- Pacoureau, Nathan; Sherley, Richard; Liu, Kwang-Ming; Sul (CEPSUL/ICMBio)), Rodrigo Barreto (Centro de Pesquisa e Conservação da Biodiversidade Marinha do Sudeste e; Katelyn Herman (Georgia Aquarium, Atlanta; Fernando, Daniel; Romanov, Evgeny; Cassandra Rigby (James Cook University, Queensland; Henning Winker (aSouth African National Biodiversity Institute, Kirstenbosch (8 November 2018). "IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: Sphyrna zygaena". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Retrieved 19 August 2020.

- "Statistics on Attacking Species of Shark". Florida Museum of Natural History. Retrieved 27 December 2017.

- "Panamanian officials find half ton of shark fins". WashingtonPost.com. Associated Press. 25 February 2011.

- Sharks Highly respected in Hawaiian Culture. Moolelo.com (2004-09-28). Retrieved on 2012-12-19.

- Compagno, L.; M. Dando & S. Fowler (2004). Sharks of the World. HarperCollins. p. 325. ISBN 978-0-00-713610-0.

- ^ Smith, M.; D. Warmolts; D. Thoney; R. Hueter, eds. (2004). Elasmobranch Husbandry Manual: Captive Care of Sharks, Rays, and their Relatives. Ohio Biological Survey. ISBN 9780867271522.

- "Babies Of The S.E.A. – Bonnethead Shark". SEA Aquarium. November 2013. Retrieved 13 September 2017.

- "The Bonnethead Shark Sphyrna tiburo: Is it Suitable for Home Aquariums?". TFH MAagazine. September 2007. Retrieved 13 September 2017.

- ^ Tristram, H.; S. Thomas; L. Squire-Junior (2014). "Husbandry of scalloped hammerhead sharks Sphyrna lewini (Griffith & Smith, 1834) at Reef HQ Aquarium, Townsville, Australia" (PDF). Der Zoologische Garten. 83 (4–6): 93–113. doi:10.1016/j.zoolgart.2014.08.002.

- "Scalloped Hammerhead, Sphyrna lewini (Griffith & Smith)". elasmollet.org. Retrieved 13 September 2017.

- "Scalloped hammerhead shark". Zootierliste. Retrieved 13 September 2017.

- "Great Hammerheads, Sphyrna mokarran (Rueppell, 1837) in Captivity". elasmollet.org. Retrieved 17 December 2015.

- McGrath, Matt (11 March 2013). "'Historic' day for shark protection". BBC News. Retrieved 27 July 2013.

- Gerhardt, Katrin (30 November 2018). "Indigenous knowledge and cultural values of hammerhead sharks in Northern Australia" (PDF). Marine Diversity Hub. Retrieved 14 November 2020.

- "Dr Ken Thaiday Senior". Australia Council. 15 May 2019. Retrieved 14 April 2020.

- "Ken Thaiday". Art Gallery NSW. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

External links

- Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.). "Family Sphyrnidae". FishBase. February 2011 version.

- Animal Diversity Web Genus Sphyrna with species sub-pages

- "Electroreception in juvenile scalloped hammerhead and sandbar sharks" by Stephen M. Kajiura and Kim N. Holland, The Journal of Experimental Biology (2002). Attempts to explain the "hammer" shape.

- Great hammerhead shark, Sphyrna mokarran, MarineBio.org

- "New shark discovered in US waters". BBC News. 10 June 2006. Retrieved 9 November 2016.

- Hammerhead Sharks, Australian Marine Conservation Society

- Hammerhead Shark - Video on Check123 - Video Encyclopedia

| Extant ground shark species | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||

| Carcharhinidae (Requiem sharks) |

| ||||||||

| Hemigaleidae (Weasel sharks) |

| ||||||||

| Leptochariidae |

| ||||||||

| Proscylliidae (Finback catsharks) |

| ||||||||

| Pseudotriakidae |

| ||||||||

| Scyliorhinidae (Catsharks) | (see Scyliorhinidae) | ||||||||

| Sphyrnidae (Hammerhead sharks) |

| ||||||||

| Triakidae (Houndsharks) |

| ||||||||