| This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. Please help to improve this article by introducing more precise citations. (August 2019) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Battle honour for British Indian Army during 1868 British Expedition to Abyssinia

Abyssinia is a battle honour awarded to units of the British Indian Army and the British Army which participated in the 1868 campaign to free Europeans held hostage in Abyssinia (now known as Ethiopia) by Emperor Tewodros II (known at that time to the British as Theodore). The success of the expedition led to the award of this honour to units of the British Indian Army which had participated in the campaign. The units belonged, with the exception of the Madras Sappers, to the Bengal and Bombay Presidency Armies.

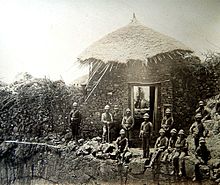

The Abyssinian Campaign of 1868

Main article: 1868 Expedition to AbyssiniaA diplomatic contretemps by the British Foreign Office led to a rupture of relations between Britain and Ethiopia. The Ethiopian monarch Tewodros had imprisoned a number of Europeans, mostly British and German, including the British Consul, Charles Duncan Cameron, in 1864. A diplomatic mission led by Hormuzd Rassam to gain their freedom, which entered the country in 1866 after numerous delays, met the same fate. In order to obtain their release and punish the offender, an expeditionary force consisting of units from the Bombay and Bengal Armies was despatched from Bombay. The force disembarked on the Red Sea south of Massawa in 1868, traversed 500 kilometres using native labour for road construction, crossed mountain ranges as high as 2,970 metres to storm the Imperial fortress at Magdala to release the prisoners. In the end, only a brief battle was fought against the men who were still loyal to Tewodros, two of the British soldiers wounded in the attack would later die from their injuries, the only other British Forces' deaths were due to disease . The Emperor committed suicide and the force withdrew.

Expeditionary Force

The Abyssinian expedition of 1868 was led by an engineer officer, Lieutenant General Sir Robert Napier, then Commander-in-Chief of the Bombay Presidency Army. The strength of the expeditionary force amounted to 14,000 men comprising four and a half regiments of cavalry, seven batteries and one Indian company of artillery, four battalions of British infantry and ten of Indian infantry.

The Engineers consisted of seven Companies of Sappers and Miners. There were four companies of Bombay Sappers and Miners under Captain (afterwards Major General) AR MacDonnell, namely Numbers 1,2,3 and 4 (that is 17, 18, 19 and 20 Field Companies). The Madras Sapper companies were G, H and K Companies. Also included was the 10th Company of the Royal Engineers.

Military Account

On 16 September 1867, a reconnoitering party sailed from Bombay. The 3rd and 4th Companies of Bombay Sappers with an advanced brigade from Bombay reached Zula on 21 October and set to work at once to build a pier at the beach. A camp was made about one mile from the sea and 20 wells were erected. The Sappers were also tasked for improving the existing track to Senafe. When the whole force was assembled, they started advancing into the hinterland. The engineering difficulties in reaching Senafe were enormous with high mountains lying ahead.

The Sappers were engaged for six weeks in making a road 10 feet wide, in some places it was carried over enormous granite boulders, by ramps. The force arrived at Senafe on 29 January 1868 and on 26 February, the main body marched from Adigrat and through the good work of a 'Pioneer' force, which included the Bombay Sappers, reached the neighbourhood of Antalo in March. The advance was resumed over increasingly barren and difficult country, where altitudes exceeded 2,900 metres, until at last General Napier arrived at Arogye, a plain at the foot of Magdala on 12 April, where the British could see the way barred, by many thousands of armed Abyssinians camped around the hillsides, with up to 30 artillery pieces.

Main article: Battle of MagdalaThe Emperor ordered an attack, with many thousands of soldiers armed with little more than spears. The 4th Regiment of Foot quickly redeployed to meet the charging mass of warriors and poured a devastating fire into their ranks. When two Indian infantry regiments contributed their firepower, the onslaught became even more devastating. Despite this, the Abyssinian soldiers continued their attack, losing over 500 with thousands more wounded during the ninety minutes of fighting, most of them at little over 30 yards from the British lines. During the chaotic battle an advance guard unit of the 33rd Regiment overpowered some of the Abyssinian artillerymen and captured their artillery pieces. The surviving Abyssinian soldiers then retreated back onto Magdala.

The following day the advance was resumed with 3,500 men against the stronghold of Magdala which was perched high on a mountain of granite and had only two entry gates. In the assault on 13 April, the Engineers led the way along a path on the side of the precipice towards one of the gates. On reaching the gate there was a pause in the advance as it was discovered the engineer unit had forgotten their powder kegs and scaling ladders and were ordered to return for them. General Staveley was not happy at any further delay and ordered the 33rd Regiment to continue the attack. Several officers and the men of the 33rd, along with an officer from the Royal Engineers, parted from the main force and, after climbing the cliff face, found their way blocked by a thorny hedge over a wall. Private James Bergin, a very tall man, used his bayonet to cut a hole in the hedge and Drummer Michael Magner climbed onto his shoulders through the hedge in the gap and dragged Private Bergin up behind him as Ensign Conner and Corporal Murphy helped shove from below. Bergin kept up a rapid rate of fire on the Koket-Bir as Magnar dragged more men through the gap in the hedge.

As more men poured through and opened fire, they advanced with their bayonets fixed, the defenders withdrew through the second gate. The party rushed the Koket-bir before it was fully closed and then took the second gate breaking through to the amba. Ensign Wynter scrambled up onto the top of the second gate and fixed the 33rd Regimental Colours to show the plateau had been taken. Private Bergin and Drummer Magner were later awarded the Victoria Cross for their part in the action.

Tewodros II was found dead inside the second gate, having shot himself with a pistol that had been a gift from Queen Victoria. When his death was announced all resistance ceased. His body was cremated and buried inside the church by the priests. The church was guarded by soldiers from the 33rd Regiment although, according to Henry M. Stanley, looted of "an infinite variety of gold, and silver and brass crosses".

Battle Honour

The honour was awarded vide Gazette of India No 1181 of 1869. It is not considered repugnant.

The following Indian units were awarded the battle honour (their present-day inheritors are listed after):

- 3rd Bombay Cavalry - Poona Horse

- 10th Bengal Cavalry - 4 Horse

- 25th (Bombay) Mountain Battery

- Madras Sappers & Miners (G, H, and K Companies) - Madras Engineer Group

- Bombay Sappers & Miners (HQ, 1st, 2nd, 3rd, and 4th Companies) - Bombay Engineer Group

- 2nd Bombay Infantry - 2nd Battalion, The Grenadiers

- 3rd Bombay Infantry - 1st Battalion, Maratha Light Infantry

- 10th Bombay Infantry - 3rd Battalion, Maratha Light Infantry presently 2nd Battalion, Parachute Regiment

- 25th Bombay Infantry - 5th Battalion, Rajputana Rifles

- 23rd Bengal Infantry (1st Bn Sikh Pioneers) - Sikh Light Infantry

- 12th Bengal Cavalry - 5 Horse (Pakistan)

- 27th Bombay Infantry - 3rd Battalion, 10th Baluch Regiment (Pakistan)

- 21st Bengal Infantry - 10th Battalion, 14th Punjab Regiment (Pakistan)

- 3rd Scinde Horse - Disbanded 1882

- 18th Bombay Infantry - Disbanded 1882

Fictional depictions

The 1868 Expedition to Abyssinia was depicted in a work of historical fiction, Flashman on the March by George MacDonald Fraser. This work was Fraser's last 'Flashman' novel.

Notes

- ^ Singh, Sarbans (1993) Battle Honours of the Indian Army 1757 - 1971. pp

- London Gazette, 28 July 1868

- Our Soldiers, by W.H.G. Kingston - Battle of Magdala, page 194

- Pankhurst, Richard. "Maqdala and its loot". Institute of Ethiopian Studies. Archived from the original on 6 December 2008. Retrieved 8 July 2008.

- Fraser, George MacDonald (2005). Flashman on the March. Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 1-4000-4475-8.

References

| This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. Please help to improve this article by introducing more precise citations. (April 2009) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

- Anonymous 1996. A brief history of the Bombay Engineer Group. The Bombay Engineer Group & Centre, Khadki, Pune. Preface & 95 pages.

- Babayya, Brig. K., Ahlawat, Col. Satpal, Kahlon, Col. H.S. & Rawat, Lt.Col. S.S. (eds) 2006 A Tradition of Valour 1820-2006 - an illustrated saga of the Bombay Sappers. The Bombay Engineer Group & Centre, Khadki, Pune. i to xvii. 280 pages.

- Sandes, Lt Col E.W.C. The Indian Sappers and Miners (1948) The Institution of Royal Engineers, Chatham. Pages i to xxx, 1 to 726, frontispiece and 30 illustrations, 31 general maps and 51 plans.

- Singh, Sarbans Battle Honours of the Indian Army 1757 - 1971.(1993) Vision Books (New Delhi) ISBN 81-7094-115-6