| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Alaska moose" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (December 2016) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

| Alaska moose | |

|---|---|

| |

| Conservation status | |

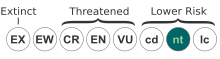

Near Threatened (IUCN 2.3) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Family: | Cervidae |

| Subfamily: | Capreolinae |

| Genus: | Alces |

| Species: | A. alces |

| Subspecies: | A. a. gigas |

| Trinomial name | |

| Alces alces gigas Miller, 1899 | |

The Alaska moose (Alces alces gigas), or Alaskan moose in Alaska, or giant moose and Yukon moose in Canada, is a subspecies of moose that ranges from Alaska to western Yukon. The Alaska moose is the largest subspecies of moose. Alaska moose inhabit boreal forests and mixed deciduous forests throughout most of Alaska and most of Western Yukon. Like all moose subspecies, the Alaska moose is usually solitary but sometimes will form small herds. Typically, they only come into contact with other moose for mating or competition for mates. Males and females select different home ranges during different seasons. This leads to spatial segregation throughout much of the year. While males and females are spatially separate the habitat that they occupy is not significantly different. During mating season, in autumn and winter, male Alaska moose become very aggressive and prone to attacking when startled.

Diet

Alaska moose have a similar diet to other moose subspecies, consisting of terrestrial vegetation forbs and shoots from trees such as willow and birch. Moose have no problem feeding on willows in this way as the nutritional value of willow twigs does not differ between original growth and regrowth after browse. Moose follow the same general migration routes every year often browsing on the same trees. Alaska moose require a daily intake of 9770 kilocalories (32 kg). Alaska moose lack upper front teeth but have eight sharp incisors on their lower jaw. They also have a tough tongue, gums and lips to help chew woody vegetation.

Size and weight

Alaska moose are sexually dimorphic with males being 40% heavier than females. Male Alaska moose can stand over 2.1 m (6.9 ft) at the shoulder, and weigh over 635 kg (1,400 lb). When Alaska moose are born, they weigh on average about 28 pounds, but by five months old they can weigh up to 280 pounds. The antlers on average have a span of 1.8 m (5.9 ft). Antler size and conformation are influenced by genetics, nutrition, and age. The antlers establish social rank and affect mating success. Female Alaska moose stand on average 1.8 m (5.9 ft) at the shoulder and can weigh close to 478 kg (1,054 lb). The largest Alaska moose was shot in western Yukon in September 1897; it weighed 820 kg (1,808 lb), and was 2.33 m (7.6 ft) tall at the shoulder. While the Alaska moose and the Asian Chukotka moose match the extinct Irish elk in size, they are smaller than Cervalces latifrons, the largest deer of all time.

Habitat

Alaska moose are almost omnipresent in Alaska. They range from Southeast Alaska to the Arctic slope in Northern Alaska, and are most likely to be found in the Northern forests. Alaskan moose are known as a Taiga species. The habitat in which they can be found is correlated with how much winter forage is exposed above the snow in winter. Since the late 1800’s the shrub to snowpack height ratio in Tundra regions surrounding boreal forests has increased by nearly one meter. This has opened more areas for moose to inhabit. In this time, the Alaskan moose has seen an expansion of extending their range farther north. While in the last century this species has extended its range they are still more densely concentrated along the major rivers in Alaska, such as the Stikine or Yukon river. They can also be found near areas that have recently experienced wildfires, since that land generates dense willow, birch, and aspen shrubs. Many moose move during mating and calving seasons, and for winter. This can take them up to 60 miles away from their normal habitats.

Social structure and reproduction

Alaska moose have no social bonds with each other and only come into contact with each other to mate, or for two bull moose to fight over mating rights. Although a bull moose is not usually aggressive towards humans, during mating season it may attack any creature it comes into contact with, including humans, wolves, other deer or even bears. Bull moose can get their antlers locked during a fight, and if so both moose can die from severe injuries or starvation. However, unlike deer, "fighting bull moose rarely lock horns as their antlers are palmated." Bull moose call out a subtle mating call to attract female moose and to warn other males. If a male moose loses to another male, he has to wait another year to mate. Alaska moose mate every year during autumn and winter, and usually produce one or two offspring at a time. At around 10–11 months, yearling Alaska moose leave their mothers and fend for themselves.

Hunting

Alaska moose are hunted for food and sport every year during fall and winter. People use both firearms and bows to hunt moose. It is estimated that at least 7,000 moose are harvested annually, mostly by residents who eat the moose meat. They are also hunted by animal predators: wolves, black bears, and brown bears all hunt moose.

References

- ^ Long, Nancy; Savikko, Kurt (August 7, 2009). "Moose: Wildlife Notebook Series – Alaska Department of Fish and Game". Adfg.state.ak.us. Archived from the original on November 30, 2009. Retrieved November 27, 2009.

- Oehlers, Susan A.; Bowyer, R. Terry; Huettmann, Falk; Person, David K.; Kessler, Winifred B. (2011). "Sex and scale: implications for habitat selection by Alaskan mooseAlces alces gigas". Wildlife Biology. 17 (1): 67–84. doi:10.2981/10-039. ISSN 0909-6396. S2CID 86133235.

- Bowyer, Terry (2003). "Effects of browsing history by Alaskan moose on regrowth and quality of feltleaf willow". Alces. 39: 193.

- ^ "Moose Species Profile, Alaska Department of Fish and Game". Adfg.alaska.gov. Retrieved 2022-02-11.

- Bord, Daniel De. "Alces alces (Eurasian elk)". Animaldiversity.org. Retrieved 2020-04-12.

- Schmidt, Jennifer I.; Hoef, Jay M. Ver; Bowyer, R. Terry (2007). "Antler Size of Alaskan Moose Alces Alces Gigas: Effects of Population Density, Hunter Harvest and Use of Guides". Wildlife Biology. 13 (1): 53–65. doi:10.2981/0909-6396(2007)13[53:ASOAMA]2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0909-6396. S2CID 54672842.

- Wood, The Guinness Book of Animal Facts and Feats. Sterling Pub Co Inc (1983), ISBN 978-0-85112-235-9

- "Cervalces latifrons". Prehistoric-fauna.com. Retrieved 2022-02-16.

- Tape, Ken D.; Gustine, David D.; Ruess, Roger W.; Adams, Layne G.; Clark, Jason A. (2016-04-13). "Range Expansion of Moose in Arctic Alaska Linked to Warming and Increased Shrub Habitat". PLOS ONE. 11 (4): e0152636. Bibcode:2016PLoSO..1152636T. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0152636. PMC 4830447. PMID 27074023.

- ^ "Moose Hunting Information, Alaska Department of Fish and Game". Adfg.alaska.gov. Retrieved 2022-02-16.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-11-03. Retrieved 2020-10-31.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - "Bull moose battle to the death | GazOutdoors Blog". Billingsgazette.com. 31 October 2012.

Further reading

- Van Ballenberghe, Victor (August 1987). "Giants of the Wilderness: Alaskan Moose". National Geographic. Vol. 172, no. 2. pp. 260–280. ISSN 0027-9358. OCLC 643483454.

| Taxon identifiers | |

|---|---|

| Alces alces gigas | |