Anarchism in China was a strong intellectual force in the reform and revolutionary movements in the early 20th century. In the years before and just after the overthrow of the Qing dynasty Chinese anarchists insisted that a true revolution could not be political, replacing one government with another, but had to overthrow traditional culture and create new social practices, especially in the family. "Anarchism" was translated into Chinese as 無政府主義 (wúzhèngfǔ zhǔyì) literally, "the doctrine of no government."

Chinese students in Japan and France eagerly sought out anarchist doctrines to first understand their home country and then to change it. These groups relied on education to create a culture in which strong government would not be needed because men and women were humane in their relations with each other in the family and in society. Groups in Paris and Tokyo published journals and translations that were eagerly read in China and the Paris group organized the Work-Study Programs to bring students to France. The late 19th and early 20th century Nihilist movement and anarchist communism in Russia were a major influence. The use of assassination as a tool was promoted by groups like the Chinese Assassination Corps, similar to the suicidal terror attacks by Russian anti-czarist groups. By the 1920s, however, the Chinese Nationalist Party and the Chinese Communist Party offered organizational strength and political change which drained support from anarchists.

Origins

Chinese anarchism has its origins in philosophical Taoism, which first developed in ancient China during the Spring and Autumn period and has been embraced by some anarchists as a source of anarchistic attitudes. The Taoist sages Lao Tzu and Zhuang Zhou whose philosophy was rather based on an "anti-polity" stance and rejection of any kind of involvement in political movements or organisations and developed a philosophy of "non-rule" in the Zhuang Zhou and Tao Te Ching, and many Taoists in response lived an anarchic lifestyle. There is an ongoing debate whether exhorting rulers not to rule belongs to the sphere of anarchism. A new generation of Taoist thinkers with anarchic leanings appeared during the chaotic Wei-Jin period. Taoist principles were more akin to philosophical anarchism, trying to delegitimate the state and question its morality. Taoism and neo-Taoism were pacifist schools of thought, in contrast with many of their Western anarchist counterparts some centuries later.

Throughout its history, Chinese civilization has gone through a cycle of rise and decline marked by the continued centralization of power by ruling dynasties, collapse of centralized rule and then the eventual rise of a new dynasty. In 1839, the Qing dynasty entered a period of decline, beginning with its defeat by foreign powers during the Opium Wars and continuing with a string of revolts and rebellions, which severely weakened the empire's centralized rule. Chinese dissidents started to flee abroad where, outside of the authority of the Qing dynasty, they were able to freely spread the revolutionary ideas of republicanism, nationalism, socialism and anarchism.

Beginnings of the reformist and revolutionary movements

During the Self-Strengthening Movement, Chinese intellectuals making direct contact with Europeans started to take an interest in the political and economic institutions of European powers. A national consciousness and a sense of cosmopolitanism began to develop, advocating the transformation of China from an empire into a nation-state, in order to secure its future existence in the face of foreign aggression. This rise in Chinese nationalism, which advocated for a form of popular sovereignty, was poorly received by the governing Confucianists, whose conservative desire to preserve the inherited institutions of the empire led them to oust many nationalists from office during the 1880s. This caused much of the nationalist movement to reconstitute itself around revolutionary republican ideals, calling for an end to Qing rule.

Inspired by early Qing thinkers that condemned rulers who prioritized private interests over the public good, the goal of the first generation of Chinese nationalists was to organically integrate Chinese society and the state, with reformers like Liang Qichao advocating for greater political participation through the institution of democracy. Contrary to the nationalists' intentions, by probing the relationship between society and the state, they had raised the question of opposition between society and the state, as well as the question of opposition between individual autonomy and the political collective, laying the foundations for the emergence of Chinese anarchist thought. These growing anarchic tendencies were even seen in Liang's own words, when he posed that his conception of nationalism "does not allow other people to infringe my freedom, nor does it let me impose on other people" and advocated for the cultivation of autonomous individuals by removing all political and social restrictions from them.

The collapse of the Self-Strengthening Movement because of the Chinese defeat in the First Sino-Japanese War gave rise to a number of new revolutionary nationalist organizations such as the Revive China Society, as well as organized political reform movements such as the Gongche Shangshu movement. From Hong Kong, the Revive China Society planned to launch an uprising in Guangzhou, but their plans were leaked and dozens of members were captured and executed by the Qing government. Meanwhile, the Guangxu Emperor had undertaken the Hundred Days' Reform, but this too was defeated in a coup d'état by the conservative faction led by Empress Dowager Cixi, who placed the reform-minded Guangxu Emperor under house arrest and ordered the public execution of the reform's chief advocates.

After the defeat of the Qing-backed Boxer Rebellion, the Qing government was finally forced to begin implementing reforms, in order to attempt to keep the dynasty in power. At the time, because of the activities of European anarchists in the late 19th century, they were frequently reported in the newspapers, but the translation used at the time was inaccurate, either phonetically as "Ya-Na-Ji-Si-De Party" (鴨那雞撕德黨) or as "Monarchless Party" (無君黨). In 1901, influenced by the Japanese translation, Liang Qichao, who was exiled in Japan, first called the American anarchist Leon Czolgosz a member of "Anarchist Party" (無政府黨) when he reported the assassination of President William McKinley in the Qing Yi Bao; because the Qing Yi Bao had great influence among intellectuals at the time, this translation soon became the most common one, however, it is generally believed that the first systematic introduction to anarchism was published much later, in a 1902 book called The Great Tide in Russia (simplified Chinese: 俄罗斯大风潮; traditional Chinese: 俄羅斯大風潮; pinyin: Eluosi Dafengchao), which was translated and expanded by Ma Junwu based on a chapter from Thomas Kirkup's A History of Socialism. Ma Junwu, Zhang Ji and the intellectuals of the time had already discussed the relationship between the Russian nihilist movement, the socialist movement in Europe and anarchism. These connections, especially with the nihilist movement, were also the general impression that anarchism left on the Chinese people at the beginning.

Early growth of anarchism

Although the emergence of anarchism as a distinct, formal political current did not occur until 1906, there were many people interested in anarchism as early as 1903. Paris was the home of the early Chinese anarchist movement, with a similar movement in Tokyo. After the failed Boxer Rebellion, local and central Chinese government groups sent students abroad for study, including some several hundred students to Europe and about 10,000 to Japan by 1906.

Paris group

Having fled the Boxer Uprising in 1900, Li Shizeng returned to Beijing the following year, where he met Zhang Renjie during a banquet at the home of a government official. The pair bonded over their mutual dissatisfaction with Chinese politics and society and discovered that they shared ideas for its reform. In 1902, the pair were appointed as attaches to the Chinese embassy in Paris, although they promptly resigned their positions so that Li should pursue an education in chemistry and biology, while Zhang founded a company to import Chinese goods. After making an acquaintance with the French anarchist geographer Élisée Reclus, Li introduced Zhang to the ideas of anarchism and they quickly began to analyze the situation in China through an anarchist lens. In 1903, Wu Zhihui fled China after having published an article in the revolutionary newspaper Su Bao, in which he criticized the Qing government and insulted the Empress Dowager. Having previously met Zhang and Li in Shanghai, Wu joined the pair in Paris, where he introduced them to his friend Cai Yuanpei, who had just published his short story the New Year's Dream, which predicted the great changes in the world with the passage of time.

In 1906 Zhang, Li, Wu and Cai founded the first Chinese anarchist organization, the World Society (Chinese: 世界社; pinyin: Shijie she), sometimes translated as New World Society. Shortly afterwards Zhang met Sun Yat-sen and was impressed by his revolutionary program, leading Zhang, Li, Wu and Cai to join the Revolutionary Alliance. But unlike their comrades in the Revolutionary Alliance, who desired a political revolution from above first-and-foremost, the Paris anarchists advocated for a social revolution from below to totally reorganize society. While the Paris anarchists tacitly supported the republican project, as they believed it would move China closer to socialism, they remained critical of republicanism and constitutionalism. According to the Paris group, political revolution was liable to bring new and more extreme inequalities, with more freedom and equality for the wealthy, while the conditions of the poor would remain the same. They observed that, in Europe, the institution of democratic and republican ideals through political revolutions had been utilized to further capitalist interests and impoverish the working classes, instead taking on a fundamentally anti-state and anti-capitalist conception for a social revolution in China. To the Paris anarchists, the goals of an anarchist revolution were the abolition of authority, laws, class distinctions and private property, for the establishment of humanitarianism, freedom, equality and communism in their respective places. The revolutionary methods they proposed to achieve these goals included propaganda, mass associations, mass uprisings, popular resistance and assassination.

Anarchist opposition to organization drew criticism from nationalists, who argued that only with an organized, strong military could China protect itself from aggressors.

Li Shizeng responded to their nationalist critics, stating the revolution that the anarchists advocated would be global, simultaneous, decentralized, and spontaneous. Thus, foreign imperialists would be too occupied with the revolutions in their home countries to bother invading or harassing China. He also argued that having a strong centralized coercive government had not prevented China's enemies from attacking her in the past anyway, and that a decentralized "people's militia" would be more effective than a standing army in defending the country.

While the Paris group advocated the destruction of hierarchical society through violence, they also held education as fundamental to constructing an anarchist society, believing that education was not only a means but an end of revolution. They declared that education was the most important activity revolutionaries could be involved in, and that only through educating the people could anarchism be achieved. According to the Paris group, anarchist education was geared towards teaching morality, truth and public-mindedness, rather than government-sponsored education which taught obedience to authority. Accordingly, they geared their activities towards education instead of assassination or grass roots organizing (the other two forms of activism which they condoned in theory). To these ends the Paris group set up a variety of businesses, including a soy products factory, which employed worker-students from China who wanted an education abroad. The students worked part-time and studied part-time, thus gaining a European education for a fraction of what it would cost otherwise. Many also gained first-hand experience on what it might mean to live, work, and study in an anarchist society. This study-abroad program played a critical role in infusing anarchist language and ideas into the broader nationalist and revolutionary movements as hundreds of students participated in the program. The approach demonstrated that anarchist organizational models based on mutual aid and cooperation were viable alternatives to profit-driven capitalist ventures.

In 1907, the group started a weekly periodical, Xin Shiji (The New Century), to introduce Chinese readers to the anarchist cause. The journal, funded by Zhang and edited by Wu, translated the works of William Godwin, Peter Kropotkin, Pierre-Joseph Proudhon and Élisée Reclus into the Chinese language. Other contributors included Wang Jingwei, Zhang Ji, and Chu Minyi, a student from Zhejiang who accompanied Zhang Renjie back from China and would be his assistant in the years to come. But after three years and over one hundred issues, the journal ceased publication, as Zhang did not have enough money to finance both its publication and the activities of the Revolutionary Alliance.

Li wrote that three fields influenced the Paris group: radical libertarianism and anarchism; Darwinism and Social Darwinism; and the classical Chinese philosophers. The well-educated, anti-traditionists of the Paris group did not relate the teachings of Lao Tzu or the ancient well-field system to modern anarchism and communism, but were still influenced by their classical education. For the Paris group, as the historian Peter Zarrow puts it, "science was truth and truth was science." The Paris anarchists favored science and rationality, advocating for a revolutionary anarchist future through the abolition of Confucian family structures and private property, the liberation of women, the promotion of individual morality and the creation of equitable social organizations.

Tokyo group

In 1903, Liu Shipei and He Zhen married and moved to Shanghai. Here the newlywed couple joined the anti-Qing Restoration Society, in which Liu developed the doctrine of guocui and edited the journal National Essence, while the Society's founder Cai Yuanpei oversaw He Zhen's education at the Patriotic Women's School. The Society's activities in Shanghai quickly attracted government suppression and the couple were forced to flee into exile in Tokyo, where they joined a group of revolutionaries that introduced them to the ideas of anarchism. The pair went on to establish the Society for the Study of Socialism, began to promote an anti-modernist and agrarianist take on anarchism. The Tokyo anarchists drew greatly from ancient Chinese philosophers such as Laozi, who the group held to be the founding father of Chinese anarchism, and Xu Xing, whose agriculturalist philosophy deeply inspired the group's agrarian utopianism. While from the works of western anarchists, the Tokyo group found inspiration in the literature of Leo Tolstoy, whose idealization of agrarianism and opposition to commercialism aligned closely with their own philosophy.

Liu Shipei argued that the Confucianist and Taoist advocacy of laissez-faire government had curtailed wider imperial intervention in society, which made China more able to achieve anarchism in the short-term than countries which had undergone the establishment of a centralized nation-state. Therefore, Liu held that the retention of the old regime was preferable to instituting a new one as, in his view, modern capitalism and parliamentarism would only contribute to a rise in economic and political inequality respectively.

In 1907, the Society began publication of the journal Natural Justice, with its stated objective being "to destroy national and racial boundaries to institute internationalism; resist all authority; overthrow all existing forms of government; institute communism; institute absolute equality of men and women." The journal became instrumental in publicizing reports on the oppressive conditions endured by women and the peasantry in Chinese society, presenting these conditions as a consequence of the rise of patriarchal family structures and urban civilization. From this position, He Zhen established the Women's Rights Recovery Association, an anarcha-feminist organization dedicated to the forceful implementation of gender equality and an end to the economic exploitation of women, proposals which were elaborated on in the article On the Question of Women's Liberation. The following year, the Society also began publication of another journal Balance, under the direction of Zhang Ji, which published some of the earliest discussions on the role of the peasantry in a social revolution. Articles in the journal called for a peasants' revolution and, inspired by the works of Peter Kropotkin, advocated for the integration of agriculture with industry.

Liu Shipei and He Zhen eventually split from the programs of Zhang Binglin and other Tokyo leaders and returned to Shanghai. When it became public that the couple had been informers working for the Manchu official Duanfang, they were shunned.

Assassination corps

Main article: Chinese Assassination CorpsWhile neither the Paris nor the Tokyo groups actively engaged in assassinations, they looked favorably on those that did. Inspired by the theory of propaganda of the deed, Chinese anarchists of the time believed that assassinations that were undertaken through self-sacrifice furthered the revolutionary cause.

In 1905, Liu Shaobin joined the Revolutionary Alliance and began to engage in assassination activities, with one failed attempt against the naval commander Li Zhun costing Liu a hand and landing him in prison for about three years. After his release, Liu began to read the anarchist literature coming from abroad and also became interested in Buddhism.

The Paris anarchist and left-wing nationalist Wang Jingwei, influenced by Russian anarchism, himself planned to assassinate the Prince-Regent, but his plan failed and he was arrested in Beijing in March 1910. In response to the failure of Wang's plan, Liu and Chen Jiongming established the Chinese Assassination Corps, which was itself influenced by foreign movements such as the People's Will and the Black Hand.

The Assassination corps was particularly active in Guangzhou, participating in the various uprisings that the city experienced at the turn of the 20th century. In the aftermath of the Second Guangzhou Uprising, one of the Qing commanders Li Chun became a target of the Chinese Assassination Corps, and was wounded in an explosive attack by the assassin Lin Kuan-tz'u.

Anarchism in the Xinhai Revolution

Starting in Guangzhou in 1895, uprisings led by the Revolutionary Alliance and its precursor Revive China Society against the Qing dynasty began to sweep throughout China, all of which failed. Chinese anarchists were generally supportive of the uprisings, believing that violence was justified if it was for moral purposes, necessary under despotic conditions, and effective if it aroused mass support for the revolutionary cause.

In reaction to the Qing government's suppression of the Railway Protection Movement, on 10 October 1911 elements of the New Army, under the influence of the Revolutionary Alliance, launched an armed rebellion against the Qing in Wuchang, deposing the local viceroy and taking control of the city. This successful uprising ignited the Xinhai Revolution, during which revolutionary republicans took up arms all around China to overthrow the Qing dynasty.

When the revolution arrived in Guangzhou on 25 October, the Qing general Fengshan was assassinated within minutes of arriving in the city by members of the Assassination Corps. Local militias were subsequently organized by the anarchist Chen Jiongming, who launched an uprising throughout Guangdong, capturing Huizhou and proclaiming the independence of the province from the Qing Empire. Many other provinces followed suit, eventually culminating in the abdication of the Xuantong Emperor and the establishment of the Republic of China.

Anarchist ideas had already been introduced to China through the literature of the Paris and Tokyo groups, enough so that Chinese radicals were able to easily distinguish between anarchism and other political philosophies. But following the Revolution and the victory of the Revolutionary Alliance, which counted several prominent anarchists as movement elders, anarchists in China took advantage of the new political openness to begin applying anarchism in practice.

By this time the Paris group had rendered their anarchism into a genuine philosophy that was more concerned with the place of the peaceful individual within society than with the day-to-day grind of government coercion against working people. The revolution allowed the Paris anarchists to return home, where they started to take a particular focus on the provision of education. When the Provisional Government was established, Cai Yuanpei was even appointed as Minister of Education. In April 1912, the Paris anarchists together founded the Diligent Work-Frugal Study Movement, in order to make education more accessible for working class students." They opened a school in Beijing to teach students the French language, in order to prepare them for study in France. When the students arrived in France, Li Shizeng arranged their admission to college and opened a workers' school near his factory, where worker-students were taught languages and science. More than 120 students were brought to France by the program, before it was closed down by Yuan Shikai. Perceiving anarchism as primarily a way to transform behavior, the Paris anarchists also established the Promote Virtue Society, which advocated for self-improvement, forbidding members from engaging in prostitution, gambling, eating meat, drinking alcohol and smoking. Although they opposed political participation and claimed to intend the overthrow of the state, the Paris anarchists were often willing to function within the state system in order to pursue their goals. Their tendency toward peace lead to increased friction between them and those comrades supportive of government coercion in Guangzhou.

In August 1912, the Revolutionary Alliance and five other small revolutionary parties were merged and reformed into the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and saw a victory in the first National Assembly election, with the Tokyo anarchists Jing Meijiu [zh] and Zhang Ji being elected. The decision of these anarchists to enter parliamentary politics was criticized by Liu Shifu for compromising anarchists principles, although it was also defended by Wu Zhihui. Shifu opposed political participation, believing that politics was a force imposed on society from above and seeing the social realm as separate from it.

However, the implementation of Nationalist rule was by no means a guarantee of freedom to organize for anti-authoritarians, and government persecution was ongoing. Meanwhile, the main ideological opposition to anarchism came from self-described Socialists, including the Chinese Socialist Society (CSS) and the left-wing nationalist movement.

The emergence of Socialism

With Nationalist political revolution having achieved its goals of overthrowing the Manchu Qing dynasty, the continued perpetuation of oppressive structures under the new Republican government generated a rise of interest in socialism, as people began to advocate for a social revolution to transform society and bring about the social ownership the means of production. Initially defined by anarchism, socialist tendencies quickly began to diversify, taking on both statist and libertarian trends.

The Tokyo anarchist Jing Meijiu was among the first to introduce socialism to China, lecturing on the subject at Shanxi University, where he advanced anarchism as the most extreme form of socialism. Inspired by the Tokyo group's abolition of distinctions between mental and manual labor, as well as the advocacy for gender equality, Jing established a worker-run women's factory in Taiyuan with the intention of providing them economic independence and fair compensation for their work, in addition to an education provided by leading Chinese anarcha-feminists.

Upon his return to China in 1910, the Paris anarchist Jiang Kanghu also began to promote socialism, which he had learnt of during his time as a contributor to the New Era. He advocated for women's education alongside socialism, which attracted the attention of Imperial authorities, although he managed to escape punishment. Shortly after the uprising against the Qing began, Jiang established the Chinese Socialist Party, the country's first socialist organization. The party had a program which advocated the abolition of racial boundaries, inheritance and all taxes except the land tax. The party grew quickly, eventually coming to claim 200 branches with 400,000 members across the country, made up of a largely heterogeneous membership which included both anarchists and social democrats. In a lecture given at a party meeting, Sun Yat-sen declared his commitment to a socialist program, which would utilize a single-tax policy and controls on monopolies, holding the ideas of Henry George alongside that of Karl Marx. Sun and Jiang were both criticised by the anarchist Liu Shifu for their claims to the leadership of the Chinese socialist movement, as well as their inclinations towards reformism, the retention of private property and state socialism. Shifu also pointed out how their socialist positions were unclear about what differentiated them from capitalism, sometimes blending the two, and often confused many different conflicting concepts for each other.

The broad socialist positions promoted by Jiang, vaguely defined by humanitarianism and utilitarianism, were often contradictory, which generated a great deal of confusion over the means and ends of socialism. While Jiang advocated for a social revolution, he also emphasized the moderate nature of his socialist ideology and rejected political violence. His socialism shared a lot in common with that of the Kuomintang, particularly in his insistence that socialism could more be easily achieved in China than in Western societies, due to the relative lack of exploitation and social divisions, and belief that socialism represented the actualization of republicanism in China, rather than presenting a threat to the existing government. He thus argued for the strengthening of republican institutions with socialism, defending that his party existed to serve the state and economic development. His aims of "absolute equality, absolute freedom, absolute love" shared a lot in common with the anarchist ideas he had picked up in the Paris group, but he believed this ideal society lay in the future, and proposed a transitional stage until Chinese workers were ready for its institution. The Socialist Party program particularly advanced policies such as the institution of public education and the abolition of inheritance, which Jiang viewed as instrumental to the achievement of socialism.

Jiang's socialism was shaped by an individualism which saw the benefitting of the self as tied together with the benefitting of others, arguing that the way to maximize the security and happiness of individuals lay in the abolition of "obstacles" such as religion, the state and the family. He blamed traditional family structures, in particular, for the oppression of women, and advocated providing women with education and work in order for them to gain independence from and equality with men. He also opposed communism, as he believed there would be those that did not contribute "from each according to their ability" that would take advantage of the communist system and that absolute equality would cause the stagnation of society. Instead he promoted equal opportunity, defending private property and different levels of payment.

The desire to retain market relations but supplement them with a broad social safety net escalated into the main source of conflict within the party. Other sources of friction had to do with the party's focus on building the revolution in China first, and using elected office as a tool to do so – both significant deviations from classical anarchism. Jiang did not call himself an anarchist, so his party was generally perceived as being outside the movement, despite the similarities. In 1912 Jiang's party split into two factions, the Pure Socialists, led by Sha Gan and Tai Xu, and the remains of the party led by Jiang.

The Buddhist anarchist monk Taixu, who had joined the Socialist Party along with many other radical monks, led the libertarian socialist faction of the party known as the "Pure Socialists". The "pure socialists" stood in opposition to Jiang's state socialism, culminating in late 1912, when the group broke entirely with the party. The program of the pure socialists sought to abolish class distinctions and eliminate all social divisions among people, seeing anarchism not just as opposition to government but as the abolition of all forms of power. The Pure Socialists revised platform included the complete abolition of property and an anarchist-communist economic system. Shifu criticized the Pure Socialists' tendencies towards nativism and nationalism, as well as for retaining the name "Socialist". As their platform was clearly of an anarchist orientation, Shifu stated that they should as such have called themselves anarchists.

Guangzhou group

Following his release from prison, Liu Shaobin began to increasingly gravitate towards anarchism and socialism, having read the materials published by the Paris and Tokyo groups, as well as the publication of the Revolutionary Alliance. As part of his activities in the Assassination Corps, he took a trip to Shanghai, in which he intended to assassinate the new head of state Yuan Shikai. However, upon arriving at a Buddhist monastery near West Lake, he renounced assassination and converted fully to anarchism, changing his name to Liu Shifu. At a meeting in Hangzhou, Shifu established the Conscience Society, an anarchist self-improvement group which took up many of the same practices as the Promote Virtue Society established by the Paris Group.

When Shifu returned to Guangzhou, he founded the Cock-Crow Society, which initially consisted largely of Shifu's family members and close friends, living together in a common household which operated as a commune. The Society spearheaded the propagation of anarchist ideas in China through the distribution of its journal the People's Voice, as well as the Paris Group's New Era and the Tokyo Group's Natural Justice. It began the teaching of Esperanto in China, which was spread by the Guangzhou anarchists to other parts of the country, driven by the internationalist program of the constructed language. The Society also initiated the labor movement in South China, with the Guangzhou anarchists becoming the first organizers of trade unions in the country and developing a strong syndicalist tendency, having particular success in organizing workers in the service industry. The city of Guangzhou quickly developed into the main base of anarchist activity in mainland China.

Shifu propagated a form of anarcho-communism that was far more radical than that of the Paris and Tokyo groups. The Guangzhou anarchists consolidated the anarchist identity by clearly distinguishing it from and formulating a number of critiques of the other forms of socialism present in China at the time. Unlike Jiang Kanghu's Socialist Party, which called for a political revolution, the Guangzhou group emphasized social revolution and advocated for the abolition of politics, drawing from the arguments of the Paris Group a decade before. Despite once remarking on the immediacy of the social revolution, Shifu noted that only a small number of people were educated on anarchism and that it would take time for people to be educated and organized before a revolution could occur. The Guangzhou group was thus chiefly tasked with distributing anarchist propaganda, in order to educate common people on the subject. In order to accelerate agitation, they also advocated for resistance to taxation and military service, labor strikes, assassinations and other forms of political violence. Eventually, they believed, propaganda would reach a saturation point and the social revolution would take place, with the common people overthrowing the state and capitalism in order to build a new anarcho-communist society.

By this time there was an extreme diffusion of anarchist ideas to the point where it was becoming difficult to define exactly who was and who was not an anarchist. Shifu set out to remedy that situation in a series of articles in Peoples Voice, which criticized Jiang Kanghu, Sun Yat-Sen, and the Pure Socialists. The letters directed at Sun Yet-Sen and the Nationalists were aimed at exposing the ambiguities of their use of the word "socialism" to describe their goals, which were clearly not socialist according to any contemporary definition. The criticisms of Jiang and the Socialist Party portrayed their vision of revolution and socialism as too narrow because it was focused on a single country, and opposed their retention of market relations as part of their platform. Meanwhile, the main criticisms of the Pure Socialists were that if they were anarchists then they should call themselves anarchists and not socialists. The Guangzhou anarchists' inclinations towards communism further differentiated them from the socialist movements of Jiang and Sun and Shifu went to great lengths to clarify the differences between anarchist and socialist currents, drawing their history back to the split in the International Workingmen's Association. Although he acknowledged Marxist contributions to socialism, he held anarchism to be more scientific than the "scientific socialism" of the Marxists, given the contributions of Peter Kropotkin to the field. He also claimed that anarchism had a broader scope than socialism, as anarchism concerned itself with society as a whole, whereas socialism was concerned chiefly with economics.

The Guangzhou group eventually went on to establish the Society of Anarcho-Communist Comrades, which advocated "absolute freedom in economic and political life" through the abolition of capitalism and establishment of a communist society, without using the state. In the Goals and Methods of the Anarchist-Communist Party, the Society called for abolition of class distinctions, the state, marriage, religion and borders, as well as the institution of common ownership of the means of production, formation of democratic public associations to coordinate the economy, universal free education, the eight-hour day, the cultivation of mutual aid and an international language. But after the death of the young Liu Shifu, the Chinese anarchist movement went through a difficult period, as reactionary forces began to gain more power.

Counterrevolution and the rise of the Warlords

In March 1913, the KMT leader Song Jiaoren was assassinated by order of the Beiyang government. In retaliation, Sun Yat-sen called for a Second Revolution to overthrow Yuan Shikai, organizing revolutionary forces of the southern provinces against the Beiyang government in an armed conflict, but the revolt was unsuccessful. Yuan subsequently dissolved parliament, abolished the constitution and reorganized provincial governments, effectively transforming the Republic of China into a dictatorship. The failure of the revolution forced Sun to flee to Japan, where he continued to receive support from Zhang Renjie, who was now making money on the Shanghai Stock Exchange.

In the political oppression that followed, many anarchist groups were forced into exile. The Guangzhou group evacuated the city, fleeing first to Macao and then on to Shanghai, where Shifu established the Society of Anarcho-Communist Comrades. A number of members of the Paris Group, including Li Shizeng, Wu Zhihui and Wang Jingwei, returned to France and relaunched the Diligent Work-Frugal Study Movement. The outbreak of World War I had seen the establishment of the Chinese Labour Corps, in which the Entente Powers recruited hundreds of thousands of Chinese workers to their factories, to which the Paris Group responded by providing these migrant workers with education and training.

In December 1915, Yuan Shikai declared himself Emperor of a new Empire of China. This was opposed by almost all the generals and officers in the Beiyang Army, with many of the Southern Provinces once again rebelling against the imperial government, beginning the National Protection War. By March 1916, the situation forced Yuan to abdicate and he died not long after. This implosion of the Beiyang government's centralized authority led to the beginning of the Warlord Era, during which the Beiyang Army fragmented into a number of regional military cliques that began to vie for control of the country.

In the aftermath, the leading KMT politician Chen Qimei was assassinated in Shanghai by the Fengtian warlord Zhang Zongchang, leading Zhang Renjie to take Chen's protégé Chiang Kai-shek under his wing, providing Chiang with financial assistance, personal advice and political backing.

Anarchism during the Third Revolution

Following the death of Yuan Shikai, a number of dissident political figures returned to China. Sun Yat-sen moved to Guangzhou, where he convened a military government with the intention of protecting provisional constitution and reuniting China, beginning the Third Revolution.

During this period, anarchists in Guangzhou initiated the Chinese syndicalist movement, organizing China's first trade unions among the city's barbers and tea-house clerks. The Guangzhou anarchists went on to lead China's first May Day celebrations, published the country's first workers' journal Labor and during the time of the Third Revolution came to have organized over forty trade unions in Guangzhou alone. Anarcho-syndicalist activity even spread as far as Hunan and Shanghai, with anarchists spearheading the education of the working classes and insisting on workers' self-organization as the backbone of the labor movement. Anarchism became a genuine popular movement in China as increasing numbers of people from peasants and factory workers to intellectuals and students became disillusioned with the national government and its inability to realize the peace and prosperity it had promised.

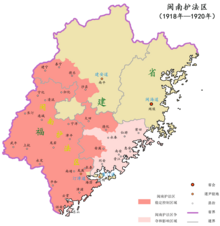

However, the First Constitutional Protection Movement was soon defeated by the Beiyang government and the Guangxi clique subsequently seized control of the military government in Guangzhou. Some of the Guangzhou anarchists subsequently fled to the Constitution Protection Region of Southern Fujian, under the protection of the anarchist military leader Chen Jiongming, who oversaw the propagation of anarchism in the city. Under Chen's leadership, Zhangzhou became a model anarchist city, where anarchists could operate and publish their literature freely. The large anarchist presence in the province led Fujian to become known as the "Soviet Russia of Southern China", with the city's anarchist publications serving as a major source of information on the progress of the Russian Revolution.

New Culture Movement

Meanwhile, in North China, Cai Yuanpei had also returned and took a position as President of Peking University, where he resumed his support for the Diligent Work-Frugal Study Movement and recruited famous thinkers such as the early Chinese communists Chen Duxiu and Li Dazhao to teach at the university. One of Li Dazhao's students was a young Mao Zedong who, initially influenced by the anarcho-communism of Peter Kropotkin, began to rapidly develop towards Marxism as part of Li's study group. The Paris Group also began to establish feeder schools throughout North China, obtaining financial support from the new Beiyang government to transport students to France, which attracted many new students to the program.

From his position at Peking University, Cai Yuanpei became a leader of the New Culture Movement, which arose out of disillusionment with traditional Chinese culture after the restored Republican government had failed to address many of the country's problems. Many of China's prominent scholars began to openly revolt against Confucianism, instead promoting a society based on individual freedom, complete with women's liberation from the patriarchy, democratic and egalitarian values, as well as a forward-looking orientation.

Many of these discussions were published in Chen Duxiu's New Youth magazine, which became a leading forum for debate on the weaknesses present in the Republic of China. The anarchist arguments for a Social Revolution that had originated a decade earlier with the original Paris group found broader acceptance in the New Culture Movement, to which anarchists introduced the first visions of socialism in China.

The movement itself was not specifically anarchist, but in its glorification of science and extreme disdain for Confucianism and traditional culture, the proliferation of anarchist thought during this period can be seen as a confirmation of the influence anarchists had on the movement from its foundation on. Anarchism, as a mass movement, was another manifestation of modernity and the most thorough criticism of empires and nation-states. At the same time, it was part of the process of modernization and globalization that swept the world before 1914. However, anarchism at this time was externally positioned as a continuum between liberalism and state socialism. The participants saw it as a conscious attempt to create a Chinese renaissance, and consciously sought to create and live the new culture that they espoused.

The New Culture Movement saw a surge in anarchist activity, with anarchist groups such as the Truth Society playing an important role in the movement at Peking University. Other pillars of the Chinese anarchist movement at the time included the Conscience Society in Guangzhou and the Masses Society in Nanjing, which later merged with the Beijing-based Truth Society to establish the Evolution Society, a nationwide anarchist umbrella organization.

May Fourth Movement

In 1919, a wave of student protests broke out throughout the country in response to the Beiyang government's weak response to the Treaty of Versailles, which had allowed the Empire of Japan to retain the territories in Shandong that it had captured from the German Empire. After student leaders of the demonstrations were arrested and imprisoned, Cai Yuanpei briefly resigned from his post as Dean of Peking University in protest, leading to a mass mobilization. News from the Russian Revolution, which Chinese radicals initially viewed as an anarcho-communist revolution, brought with it a new-found interest in socialism. Anarchists greatly benefited from the new interest in socialism, as anarchism was the most popular and widespread variant of socialism at the time.

The Beiyang government became increasingly concerned with the surge in anarchist activity and began to identify extremism closely with anarchism, counterintuitively giving more publicity to the anarchist movement. Anarchist societies began to spring up across China and anarchist ideas became central to Chinese radicalism, with the New Life Movement bringing anarchist principles into everyday life, through the creation of agrarian communes. According to Zhou Zuoren, a leading figure in the movement, the main goal of these new villages was conceived as being the promotion of labor, which anarchists of the time held to be the foundation of future society. The anarchist conceptions of mutualism and education were also fundamental aspects in these experiments to reorganize social life. Anarchists of the May Fourth Movement refused to distinguish between means and ends, holding that the process of revolution lay in the creation of the future society in the present. However, these communal experiments quickly failed, with the groups involved falling victim to financial difficulties, as the situation had made economic enterprise and employment more difficult. But these short-lived communal experiments still provided inspiration for China's left-leaning intellectuals, who saw them as the beginning of a new era in human society.

The newfound interest in socialism brought on by the movement also brought with it a surge in Marxism. It was at this time that the first Bolsheviks started organizing in China and began contacting anarchist groups for aid and support. The anarchists, unaware that Bolsheviks had taken control in the Soviets and would suppress anarchism, helped them set up communist study groups – many of which were originally majority anarchist – and introduced Bolshevism into the Chinese labor and student movements. Chen Duxiu, a vocal opponent of anarchism, became more interested in Marxism during this period and went on to found the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). The CCP was itself founded on the basis of student associations that had been inspired by anarchism during the May Fourth Movement, particularly by the principles of mutual aid and the practice of labor that had been foundational to the organization of collective living in rural areas. Some of the student activists that had arrived at Communism through their association with anarchism included the agrarian movement pioneer Peng Pai and the future CCP leader Mao Zedong.

Suppression of the anarchist movement by Beiyang government

After the Xinhai Revolution, the main target of anarchist opposition shifted from the original autocratic empire to warlord politics, and thus was again suppressed by the Beiyang government. A large number of publications were banned or prohibited from circulation by the Beiyang government, and No. 1165 Document of the Ministry of Transportation and Communications of the Beiyang government stated that "Anarchism is not tolerated in all countries of the world, and since there are such secret societies in Shanghai, they are bound to secretly collude with each other and spread more and more. The printed materials should be banned from circulation to avoid the harm."

The Beiyang government also sent government agents to monitor the actions of the anarchists. From February to April 1921, the Beijing government sent secret agents disguised as students seven times to infiltrate and sabotage the anarchist groups. Anarchism, anarcho-communism, and communism were all suppressed as "extreme" ideas during this period.

Second Constitutional Protection Movement

In 1920, the anarchist military leader Chen Jiongming launched an attack on the Guangxi clique, which had taken over the Constitutional Protection Junta in Guangzhou. Chen recaptured Guangdong for the KMT and even went on to occupy Guangxi, seeing the ultimate dissolution of the Guangxi clique. Chen subsequently invited Sun Yat-sen to return to Guangzhou, where a parliament was reconvened and a new government was established, beginning the Second Constitutional Protection Movement. But as the government was unrecognized and lacking in numbers, Chen invited anarchists, communists and federalists to join the movement, to the chagrin of Sun. Chen also became instrumental in organizing the labour movement of South China, securing workers with the right to collective bargaining. During the Guangzhou seamen's strike, Chen helped to settle the strike, with the employers capitulating to the demands of wage increases.

Sun Yat-sen proposed to forcibly unify China under centralized one-party rule, whereas Chen Jiongming opposed this idea, instead advocating for the establishment of a multi-party federal China through the implementation of inter-provincial autonomy. This split hit its apex when Li Yuanhong was reinstated as President of China, with Chen Jiongming declaring the success of the constitutional protection movement and calling for Sun Yat-sen to step down. When Sun refused, Chen organized a military revolt against the Guangzhou government, forcing Sun Yat-sen to flee once again to Shanghai. But Tang Jiyao eventually retook Guangzhou for the KMT, forcing Chen to flee himself, first to Huizhou then to Hong Kong. Sun Yat-sen himself returned to Guangzhou, where he re-established the military government.

Anarchists in the First United Front

By 1923, Sun Yat-sen was beginning to put into practice his plans for the military conquest of North China. In order to speed up the process, he signed an agreement to cooperate with the Soviet Union, and subsequently formed an alliance with the newly established Chinese Communist Party (CCP), establishing the First United Front. In his lectures on the Three Principles of the People, Sun even began to downplay the differences between the socialist ideology of the Kuomintang and that of the anarchists and communists, going as far as to state that the ultimate goal of the Three Principles was the establishment of anarchist communism. To Sun, the principle of People's Livelihood was the realization of communism, clarifying that he advocated the methods proposed by Proudhon and Bakunin, while considering that Marxism was not "real communism".

While these statements accelerated the Chinese anarchist effort to appropriate the Three Principles, it also opened the door for the appropriation of anarchism by the Kuomintang. Anarchists saw their loyalties divided and their anarchist goals subordinated to that of the party. The Central Supervisory Committee of the KMT even came under the influence of veteran anarchists, such as the Paris anarchists Li Shizeng, Wu Zhihui and Zhang Renjie, who fiercely criticized the KMT's alliance with the CCP. Wu argued that the anarchist involvement in the KMT was necessary to counter the warlords and justified his support for the party due to its commitment to revolution, pointing to Peter Kropotkin's support for the Entente in World War I as an example of anarchists supporting progressive causes that were not their own. But few anarchists looked favorably on this collaboration with the KMT, with some even calling the party counter-revolutionary and criticizing what they saw as opportunism among the KMT anarchists, ultimately causing a division within the anarchist movement which led to the beginning of its downfall. The actual result of such collaboration was that the anarchists, not the Nationalists, compromised their positions since doing so allowed them to gain access to power positions in the Nationalist government that they theoretically opposed.

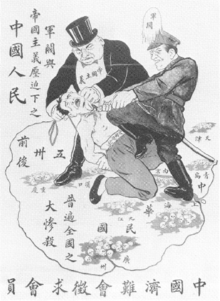

With the exception of in Guangzhou, the Chinese anarchist movement largely lost ground to the Communist Party. When it was suggested that the Communist Party headquarters be moved from Shanghai to Sun's base in Guangzhou, Chen Duxiu responded by saying "Anarchists are all over this place, spreading slanderous rumors about us. How can we move to Guangzhou?" The tension with communists was increased by anarchist criticisms of the Soviet Union. Reports from disillusioned anarchists had a big impact, such as Emma Goldman, who had many friends in China, and the wife of Kropotkin, who circulated first-hand reports of the failures of Bolshevism. By this time, more than seventy Chinese anarchist publications were in active distribution, both inside and outside of mainland China, which became increasingly focused on the criticism of Bolshevism and the Soviet Union. In their critiques of Bolshevism, anarchists even went as far as to reject class conflict as a means of resolving class oppression, regarding it as a selfish way of perpetuating the same social relations under a different guise, holding instead that the abolition of authority was the means of achieving a classless society. Expressions of anarchism also beginning to take on a more radical and violent character, influenced by the theory of propaganda of the deed. The Manifesto of Hunan anarchists even included a declaration that "one bomb is better than a thousand books."

Succession crisis

With the death of Sun Yat-sen in March 1925, a power struggle emerged within the Kuomintang, with the left-wing Wang Jingwei, the centrist Chiang Kai-shek and the right-wing Hu Hanmin all vying for control of the party apparatus. Suspected of having assassinated the KMT chairman Liao Zhongkai for supporting the continuation of the United Front, Hu Hanmin was arrested and exiled by Wang and Chiang, which resulted in the right-wing faction of the KMT losing power. Meanwhile, the Yunnan clique had revolted against the KMT's acting executive, claiming Tang Jiyao to be the rightful leader of the KMT. But Tang's forces were routed by the New Guangxi clique and he fled to San Francisco, where Tang joined with Chen Jiongming to found the Public Interest Party, a political party that advocated for federalism and multi-party democracy.

May Thirtieth Movement

On 30 May 1925, Chinese students gathered at the Shanghai International Settlement and held a demonstration against foreign intervention in China. Supported by the KMT, they called for a boycott of foreign goods and an end to the Settlement. The British-operated Shanghai Municipal Police opened fire on the crowd of demonstrators, killing at least nine. This incident sparked outrage throughout China, which culminated in a strike in Guangdong and proved a fertile recruiting ground for the CCP. The aftermath of the May Thirtieth Movement brought on a massive surge in the influence of the Communist Party, growing from having about one thousand members to over fifty thousand and establishing their supremacy over the Chinese labor movement, displacing the existing anarcho-syndicalist leadership. As well as the loss of their influence in the labor movement, anarchists were also losing influence among the youth, who were becoming increasingly attracted to nationalism.

In the self-criticism that the anarchist movement undertook in the ensuing years, anarchists identified their failings in their inability to organize a national revolutionary movement, instead having largely focused on local struggles, as well as their refusal to engage in non-anarchist revolutionary activity. This led many anarchists, who had previously been critical of anarchist collaboration with the Kuomintang, to raise questions on whether or not to participate in the party. Some anarchists such as Ba Jin were opposed to direct collaboration with the revolutionary parties, but instead obliged anarchists to participate in the popular revolution itself and guide people toward anarchism. Others were willing to collaborate with the KMT, on the condition that they retain their anarchist identity and push the party towards anarchist revolutionary goals, which was a perspective encouraged by the Paris anarchists.

Rise of the Kuomintang and the decline of anarchism

The rising power of the left-wing brought increased tensions within the United Front as Chiang Kai-shek began to consolidate power in preparation for the Northern Expedition. The former leaders of the Paris anarchist group Zhang Renjie, Li Shizeng, Wu Zhihui and Cai Yuanpei had become known as the Four Elders of the Kuomintang, holding strong influence over the party and supporting Chiang Kai-shek's candidacy for the leadership. The Four Elders took a hardline stance against the communists as well as the left-wing of the KMT, who perceived their activities as threatening an anarchist takeover of the party.

Division of the United Front

On 20 March 1926, Chiang Kai-shek launched the Canton Coup, purging hardline communists who opposed the proposed Northern Expedition. In an attempt to balance the need for communist assistance with his concerns about growing communist influence, After Zhang Renjie counseled Chiang against identifying himself too closely with the right, Chiang negotiated the removal of hardline members of the KMT's right-wing faction from their posts in compensation for the purged leftists. Soviet aid to the KMT government continued, as did co-operation with the CCP, holding together the United Front long enough to lay the groundwork for the Northern Expedition.

The first phase of the expedition began in July 1926, capturing the provinces of Hunan, Hubei and Henan from the forces of Wu Peifu, and the provinces of Fujian, Jiangxi, Zhejiang, Anhui and Jiangsu from the forces of Sun Chuanfang, eliminating the Zhili clique in the process. The headquarters of the nationalist government subsequently moved from Guangzhou to Wuhan, while Communist-led trade unions began establishing parallel structures in the areas that had been captured by the National Revolutionary Army. Independent peasant rebels also began to take control of large swaths of land and started to govern themselves, which in response alienated much of the KMT's military leadership, who were generally opposed to peasant self-rule.

The Wuhan government, which was controlled by Wang Jingwei's leftist faction of the KMT, aided by the CCP, as well as widespread grassroots support, transformed Wuhan into "a seedbed for revolution", while portraying themselves as the sole legitimate leadership of the KMT. Controlling much of Hunan, Hubei, Guangdong and Jiangxi, the Wuhan government began challenging Chiang's authority, nominally stripping him of much of his military authority, though refrained from deposing him as commander-in-chief. The CCP also became an equal partner in the Wuhan government, sharing power with the KMT leftists. In response to these developments, Chiang started to rally anti-communist elements in the KMT and NRA around him.

When the Northern Expedition arrived in Nanjing, a series of anti-foreigner riots broke out in the city, with the ensuing chaos bringing the expedition's advance to a halt as Chiang blamed the Communists for instigating the incident. In April 1927, the Four Elders determined that the actions of the CCP were counter-revolutionary and urged Chiang Kai-shek to initiate a purge of the leftists, culminating in the Shanghai massacre, during which thousands of communists were arrested and killed, effectively ending the First United Front. Despite this causing a split between Chiang's right-wing government in Nanjing and Wang Jingwei's left-wing government in Wuhan, further unrest between the two parties and Soviet interference in the Wuhan government caused Wang to himself initiate a purge of communists from his own ranks. The Wuhan government subsequently re-unified with the Nationalist government in Nanjing, on the condition that Chiang resigned from his post. However, following the suppression of a number of communist uprisings in Nanchang, Hunan and Guangzhou, Chiang Kai-shek retook power from Wang Jingwei, who went into exile in Europe.

The National Labor University

In the aftermath of the Shanghai Massacre, the Four Elders convinced several prominent anarcho-syndicalists in the Shanghai labor movement to join them in the KMT, bringing together a significant anarchist presence within the party. One of the projects these anarchists proposed was the establishment of a workers' university, which would train and educate a new kind of "worker-intellectual" in order to transform the nation as a whole. The KMT anarchists also published a new periodical called Revolution Weekly, to propagate anarchist ideas that were appropriate for continued collaboration between anarchists and the KMT, taking the Three Principles of the People as a means to achieve the goal of anarchism.

In late 1927, the National Labor University was established in Shanghai, with the goal of realizing the anarchist ideal of combining labor with education, by turning "schools into fields and factories, fields and factories into schools." The anarchists believed that this would be a means to peacefully abolish class distinctions and achieve a social revolution, bringing China further towards anarchism. Faculty at the university criticized contemporary Chinese education for its emphasis on reading "dead books", advocating instead for a "living education" which came through the practice of labor.

The formation of the university was overseen by Cai Yuanpei, who had experience as head of Peking University and was busy supervising the broader restructuring of the education system in the Republic of China, with Yi Pei Chi being appointed as the university's president. It was decided that the university would follow the model of public education, with students recruited from working-class backgrounds, in order to end the monopolization of education by the rich. Initially an institution of higher education, elementary and middle schools were eventually added to the university, transforming it into a truly comprehensive educational institution. The university comprised an Industrial Labor College, an Agricultural Labor College and a Social Sciences College, along with a library that held an inventory of over forty thousand books.

Students generally attended classes in the morning, while doing manual labor in the fields and factories during the afternoon. Industrial Labor students worked on machines or setting type in print shops, Agricultural Labor students worked the fields or on irrigation, successfully cultivating tomatoes and cauliflower, while Social Sciences students conducted surveys on social problems and labor strikes in nearby villages. Students were also encouraged to engage in a variety of extracurricular activities, with each college having its own theater group, such that classwork and manual labor did not preclude their leisure time.

However, the number of students that enrolled did not meet the planned numbers, due in part to the university's de-emphasis of strictly academic work, the stigma still attached to manual labor and the effort to recruit students from working-class backgrounds. The Nationalist government was also increasingly replacing the decentralized socialist education system of Cai Yuanpei with a centralized education system. Access to resources were curtailed and the Labor University eventually ceased operations altogether, due to the conditions created by the January 28 incident.

Suppression of the anarchist movement by KMT and CCP

The Second phase of the Northern Expedition finally forced the dissolution of the Beiyang government, with the Northeast Flag Replacement marking the achievement of the Nationalist government's supremacy over the Republic of China. Chiang Kai-shek subsequently centralized authority under the Kuomintang, quickly transforming the country into a one-party state and resolving to terminate mass movements, which he concluded were no longer necessary now that a revolutionary party held state power. In particular, the continuing existence of the anarchist movement presented a clear and present threat to the authoritarian rule of the KMT, which resolved to undertake the suppression of anarchism in China.

When the KMT initiated a second wave of repression against the few remaining mass movements, anarchists left the organization en masse and were forced underground as hostilities between the KMT and CCP – both of whom were hostile towards anti-authoritarians – escalated. Previously sympathetic to the KMT, articles in the anarchist periodical Revolution Weekly began to question the party's revolutionary credentials, citing its murder of striking workers in Shanghai and the prevalence of warlords in the KMT's ranks, leading it to conclude that there had been a continuation of collusion between capitalists and the new regime. Anarchists argued that the revolution had been a solely political revolution and that the KMT had abandoned its previously held promises of social revolution, holding instead that the revolution's success rested in the proliferation of the KMT in power and labeling any people that called for freedom or the improvement of their own lives as "counterrevolutionaries".

The Four Elders were among the targets of criticism by anarchists, identifying Wu Zhihui in particular as an enabler of Chiang Kai-shek and calling for the KMT anarchists to resign their posts and cease their activities within the party and the government. The left-wing faction of the KMT was blamed for the attacks on the Four Elders and, as the criticisms of the party continued, Revolution Weekly was proscribed throughout China and shut down in September 1929. In its final issue, an editorial stated that anarchists "had survived the Communists and the Northern Expedition" but "finally succumbed to the Kuomintang, which had promised free speech to all." Anarchists themselves started to be hunted down by the authorities, charged with conspiring to take over the party or even being labelled as communists. By the end of the 1920s, the anarchists, betrayed by the Kuomintang in their struggle against Marxism, exhausted their utility and slowly disappeared as a force in the Chinese revolutionary movement.

Nevertheless, some anarchists continued to collaborate with the Kuomintang, although they were now being sidelined by Chiang Kai-shek. Zhang Renjie took a position as governor of Zhejiang, where he oversaw a number of public infrastructure projects, before they were eventually sold to private firms, after which he broke with Chiang and resigned, later retiring from politics altogether. Despite initially denying any government office, Wu Zhihui was eventually elected to the National Assembly, where he helped to draft a new constitution and administered the oath of office to Chiang. Cai Yuanpei took a more combative approach, founding the China League for Civil Rights which openly criticized Chiang's government for abuse of power and political repression, though he soon retired from public view after the league's co-founder was murdered in front of the organization's offices in Shanghai.

Insurgent communism and the rise of Maoism

Following the suppression of the anarchist movement and the capitulation of the left-wing nationalists in the Kuomintang, the Chinese Communist Party became the de facto leader of the left-wing opposition to the Nationalist government of Chiang Kai-shek. The Communists themselves had been driven underground and forced to flee to the countryside by nationalist persecution, leading them to begin building a base among the rural peasantry.

To fight back against the Nationalists, the Communists established the Chinese Red Army, launching their first uprising against the government in Nanchang and beginning the Chinese Civil War. Initially successful, the Red Army was forced to retreat by a nationalist counter-offensive, withdrawing to the mountains of south-western Jiangxi. Another uprising in Changsha, but this was defeated and the survivors retreated to the Jinggang Mountains, where Mao Zedong established a base, uniting five villages into a self-governing territory and implementing a policy of confiscating lands from rich landowners. It was here that Mao began to advocate for a peasant-based revolution, contrary to the Communist Party's favor towards urban cadres, in order to overthrow the "four systems of authority" (state, clan, religion and patriarchy). However, after a number of KMT attacks against their base, Mao's forces were eventually forced to evacuate south. Despite coming into conflict with the new leadership of the CCP for his agrarianist position, initiating a purge of dissenters and repressing a rebellion against him, Mao was able to establish the Chinese Soviet Republic with the Jiangxi–Fujian Soviet as his revolutionary base area and was able to defeat both the first and second encirclement campaigns against it through the use of guerrilla tactics.

The KMT was eventually forced to retreat in order to deal with Japanese incursions into China, which allowed the Soviet Republic to expand its influence, with Mao initiating a wide-ranging program of land reform, education and increased gender equality. However, the KMT eventually returned to Jiangxi, viewing the Communists as a greater threat than the Japanese, and initiated a fifth encirclement campaign, bringing about the dissolution of the Jiangxi Soviet and forcing the Red Army into a retreat. After a year on the run and having survived numerous attacks, Mao's army eventually arrived at the Shaanxi Soviet, establishing Yan'an as their revolutionary base area. It was here that Mao developed the concept of the "mass line", which attempted to overcome the centralizing and bureaucratic tendencies of Marxism-Leninism by consulting the masses and carrying out the perceived will of the majority.

China at war

Despite centralizing power over the Yangtze Delta region, the Nationalist government did not hold complete control over China, as a number of regional warlords still remained. In the wake of the assassination of the Fengtian warlord Zhang Zuolin, a power vacuum left behind in Manchuria presented an opportunity for the numerous Korean anarchists that were organized in the region. The Korean People's Association in Manchuria (KPAM) subsequently established an autonomous anarchist zone in Mudanjiang, organized along anarcho-communist lines around the principles of individual freedom and mutual aid. However, the Korean anarchists soon fell victim to attacks by the Empire of Japan, culminating in the Japanese invasion of Manchuria, which dissolved the KPAM and established a puppet state known as Manchukuo. From Hong Kong, Chen Jiongming responded to the invasion by attacking Chiang Kai-shek's regime for its appeasement policy and organizing boycotts of Japanese products.

The Empire of Japan continued to conquer more and more regions of China, including Shanghai in 1932 and Rehe in 1933, while also setting up zones of influence throughout North China, establishing puppet states in the Hebei, Chahar and Mengjiang. Despite attempts by volunteers to resist the Japanese incursions in Manchuria and Inner Mongolia, by 1937 the Empire of Japan had launched a full-scale invasion of China, beginning the Second Sino-Japanese War.

The Nationalist government had previously been engaging in a number of encirclement campaigns, in an attempt to isolate and destroy the Chinese Soviet Republic, rather than focusing on the threat posed by the Empire of Japan. But following the Xi'an Incident, during which Chiang Kai-shek was detained by two of his subordinates, the Second United Front was established to resist the Japanese invasion. The CCP and KMT fought together in the Battle of Taiyuan and the Battle of Wuhan, losing both to the Empire of Japan, but the two operated largely independently of each other, with the communists favoring guerrilla warfare over conventional battles. In January 1941, a clash between the two parties known as the New Fourth Army incident brought the Second United Front to an end, after which they resumed hostilities.

When a number of attempts to form a series of anti-Chiang Kai-shek governments were suppressed, Wang Jingwei went into exile in Europe, where he began to form relations with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy, marking a shift to the far-right for the once left-wing KMT leader. As Chiang began to argue for a rapprochement with the Soviet Union, Wang argued for bringing China into an alliance with the Axis Powers. After an assassination attempt by the KMT, Wang fled to Japanese-held territory, where he negotiated the establishment of a Reorganized National Government under his control. Among the figures in the collaborationist government were the Chief of the Education Yuan Jiang Kanghu, the founder of the Socialist Party, and the Foreign Minister Chu Minyi, who had met Wang when they were both members of the Paris anarchist group. In a massive reversal of his previously held views, Wang blamed communism, anarchism and internationalism for the decadence of Modern China, arguing for the necessity of promoting Confucianism in a return to traditional values.

Following the attack on Pearl Harbor, the Allies began to support the Republic of China against the Empire of Japan, turning the tide of the war. Eventually the surrender of Japan saw China recover all the territories that it had lost to the Empire of Japan since the Treaty of Shimonoseki, including Taiwan. After the war, the Chinese Communist Revolution commenced, during which the CCP took control of mainland China and established the People's Republic of China, forcing the leadership of the KMT to retreat to Taiwan. After 1949, there were few visible signs of anarchist activity in neighboring countries or among overseas Chinese, and the post-revolutionary revival of interest in anarchism was short-lived.

Anarchism in the People's Republic

| Part of a series on |

| Maoism |

|---|

|

Concepts

|

| Variants |

People

|

Theoretical works

|

History

|

Organizations

|

| Related topics |

At the advent of the Chinese Communist Revolution, many Chinese anarchists fled abroad to Hong Kong or Taiwan, with some even going as far as France or the United States, although others also chose to remain in mainland China. One of those that remained was the anarchist writer Ba Jin, who was obliged to join the China Writers Association, saw his works censored to remove any mentions of anarchism and largely ceased writing. During the Anti-Rightist Campaign, Ba Jin denounced writers that were accused of right-wing deviationism.

With the beginning of the Great Leap Forward, the people's communes were established with the intention of "performing the functions of state power" and taking on a vital role in the transition from socialism to communism, being treated as the first step in the "withering away of the state". This promise of an end to statism was particularly appealing to many Chinese peasants, who were attracted to the communes by their aspirations of freedom from state officials and party bureaucrats. According to Maurice Meisner, "ad the people's communes actually developed in the manner Maoists originally envisioned, centralized political power in China would have been fundamentally undermined."

Following a series of strike actions by the peasantry, party officials implemented a "rectification campaign" in order to combat the rising egalitarianism in the communes. Mao himself commented on the state of the communes that: "there is now semi-anarchism We should now emphasize unified leadership and centralization of powers. Powers granted should be properly retracted. There should be proper control over the lower level." After a series of party meetings, bureaucratic authority was reasserted over the rural cadres and centralized state control of the communes was established, reintroducing private ownership and resolving to distribute resources based on work output rather than individual needs. The subsequent bureaucratic mismanagement, combined with other factors, led to tens of millions dying in the Great Chinese Famine from 1959 to 1961.

Anarchic tendencies within the Cultural Revolution

During the Cultural Revolution, a number of anarchistic tendencies began to spread throughout China, advocating for a popular "revolution from below" in opposition to the bureaucratic tendencies of the Communist Party and inspired by the Maoist slogan "Dare to rebel". In the early months of the revolution, the city of Shanghai was targeted by Maoists for the seizure of power from local communist party officials. On 5 January 1967, the "Worker's Headquarters" issued a call for the unity of Shanghai's workers, students, intellectuals and cadres, deposed the city's officials and established the Shanghai People's Commune. After Yao Wenyuan, Zhang Chunqiao and Wang Hongwen took power as the leaders of the commune, various workers' organizations began to challenge the newly appointed city government and organized around the slogan of "All power to the Commune". However, Maoist leaders in Beijing had begun to favor the model of the revolutionary committee for the reorganization of political society. During a meeting with Zhang and Yao, after hearing that many Shanghai Communards were now demanding the abolition of political authority in the commune, Mao himself expressed his opinion on the communards' demands: "This is extreme anarchism, it is most reactionary... In reality there will always be heads."

After the suppression of the Shanghai People's Commune and the institution of a revolutionary committee in the city, Mao turned his attention towards eliminating the anarchistic tendencies that had been unleashed by the Cultural Revolution. He declared that the revolutionary slogan "doubt everything and overthrow everything" was "reactionary", banned radical workers' organizations for being "counter-revolutionary" and instituted strict punishments for attacks against the party and the state. The ultra-left May Sixteenth elements, which had been blamed for much of the chaos by Maoist leaders, were outlawed on charges of "anarchism" and a nationwide campaign was carried out to liquidate the organization.

Out of these struggles between the grassroots and the leadership of the revolution, the radical Maoist group Shengwulian (Hunan Provincial Proletarian Revolutionary Great Alliance Committee) was formed in Hunan province during late 1967. The group took on a staunchly anti-bureaucratic line against what they saw as the "Red capitalist class", which had retained control of the state through the newly established revolutionary committees. In its manifesto Whither China?, the Shengwulian declared its goal was a mass revolution to "smash the old state machinery" and establish in its place the "People's Commune of China", a new society without bureaucrats where the masses would be in control. Despite the Shengwulian pledging its fealty to Mao and the Cultural Revolution Group, the group was denounced as "anarchists" and violently suppressed by the People's Liberation Army (PLA) and the Ministry of State Security (MSS).