| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Five Suns" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (November 2022) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

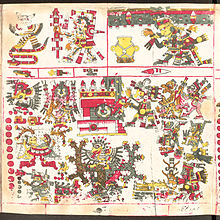

In creation myths, the term "Five Suns" refers to the belief of certain Nahua cultures and Aztec peoples that the world has gone through five distinct cycles of creation and destruction, with the current era being the fifth. It is primarily derived from a combination of myths, cosmologies, and eschatological beliefs that were originally held by pre-Columbian peoples in the Mesoamerican region, including central Mexico, and it is part of a larger mythology of Fifth World or Fifth Sun beliefs.

The late Postclassic Aztecs created and developed their own version of the "Five Suns" myth, which incorporated and transformed elements from previous Mesoamerican creation myths, while also introducing new ideas that were specific to their culture.

In the Aztec and other Nahua creation myths, it was believed that the universe had gone through four iterations before the current one, and each of these prior worlds had been destroyed by Gods due to the behavior of its inhabitants.

The current world is a product of the Aztecs' self-imposed mission to provide Tlazcaltiliztli to the sun, giving it the nourishment it needs to stay in existence and ensuring that the entire universe remains in balance. Thus, the Aztecs’ sacrificial rituals were essential to the functioning of the world, and ultimately to its continued survival.

Legend

According to the legend, from the void that was the rest of the universe, the first god, Ometeotl, created itself. The nature of Ometeotl, the "God of duality" was both male and female, shared by Ometecuhtli, "Lord of duality," and Omecihuatl, "Lady of duality". Ometeotl gave birth to four children, the four Tezcatlipocas, who each preside over one of the four cardinal directions. Over the West presides the White Tezcatlipoca, Quetzalcoatl, the god of light, mercy and wind. Over the South presides the Blue Tezcatlipoca, Huitzilopochtli, the god of war. Over the East presides the Red Tezcatlipoca, Xipe Totec, the god of gold, farming and spring time. And over the North presides the Black Tezcatlipoca, also called simply Tezcatlipoca, the god of judgment, night, deceit, sorcery and the Earth.

The Aztecs believed that the gods created the universe at Teotihuacan. The name Teōtīhuacān was given by the Nahuatl-speaking Aztecs centuries after the fall of the city around 550 CE. The term has been glossed as "birthplace of the gods", or "place where gods were born", reflecting Nahua creation myths that were said to occur in Teotihuacan.

First sun

It was four gods who eventually created all the other gods and the world we know today, but before they could create they had to destroy, for every time they attempted to create something, it would fall into the water beneath them and be eaten by Cipactli, the giant earth crocodile, who swam through the water with mouths at every one of her joints. From the four Tezcatlipocas descended the first people who were giants. They created the other gods, the most important of whom were the water gods: Tlaloc, the god of rain and fertility and Chalchiuhtlicue, the goddess of lakes, rivers and oceans and also the goddess of beauty. To give light, they needed a god to become the sun and the Black Tezcatlipoca was chosen, but either because he had lost a leg or because he was god of the night, he only managed to become half a sun. The world continued on in this way for some time, but a sibling rivalry grew between Quetzalcoatl and his brother the mighty sun, who Quetzalcoatl eventually decided to knock from the sky with a stone club. With no sun, the world was totally black and in his anger, Tezcatlipoca commanded his jaguars to eat all the people.

Second sun

The gods created humans who were of normal stature, with Quetzalcoatl serving as the sun for the new civilization, as an attempt to bring balance to the world, but their attempts ultimately failed as humans began to drift away from the beliefs and teachings of the gods and instead embraced greed and corruption.

As a consequence, Tezcatlipoca showcased his dominance and strength as a god of magic and justice by transforming the human-like people into monkeys. Quetzalcoatl, who had held the flawed people in great regard, was greatly distressed and sent away the monkeys with a powerful hurricane. After they were banished, Quetzalcoatl stepped down from his role as the sun and crafted a new, more perfect race of humans.

Third sun

Tlaloc was crowned the new sun, but Tezcatlipoca, the mischievous god, tricked and deceived him, snatching away the love of his life, Xochiquetzal, the deity of beauty, flowers, and corn.

Tlaloc had become so consumed by his own grief and sorrow that he was no longer able to fulfil his duties as the sun; therefore, a great drought befell the people of the world. People desperately prayed for rain and begged for mercy, but their pleas fell on deaf ears.

In a fit of rage, Tlaloc unleashed a rain of fire upon the earth, completely destroying it and leaving nothing but ashes in its wake. Following this cataclysmic event, the gods then worked together to create a new earth, allowing life to be reborn from the seemingly lifeless and barren land.

Fourth sun

The next sun and also Tlaloc's new wife, was Chalchiuhtlicue. She was very loving towards the people, but Tezcatlipoca was not. Both the people and Chalchiuhtlicue felt his judgement when he told the water goddess that she was not truly loving and only faked kindness out of selfishness to gain the people's praise. Chalchiuhtlicue was so crushed by these words that she cried blood for the next fifty-two years, causing a horrific flood that drowned everyone on Earth. Humans became fish in order to survive.

Fifth sun

Quetzalcoatl would not accept the destruction of his people and went to the underworld where he stole their bones from the god Mictlantecuhtli. He dipped these bones in his own blood to resurrect his people, who reopened their eyes to a sky illuminated by the current sun, Huitzilopochtli.

The Centzonhuītznāhua, or the stars of the south, became jealous of their brighter, more important brother Huitzilopochtli. Their leader, Coyolxauhqui, goddess of the moon, led them in an assault on the sun and every night they come close to victory when they shine throughout the sky, but are beaten back by the mighty Huitzilopochtli who rules the daytime sky. To aid this all-important god in his continuing war, the Aztecs offer him the nourishment of human sacrifices. They also offer human sacrifices to Tezcatlipoca in fear of his judgment, offer their own blood to Quetzalcoatl, who opposes fatal sacrifices, in thanks of his blood sacrifice for them and give offerings to many other gods for many purposes. Should these sacrifices cease, or should mankind fail to please the gods for any other reason, this fifth sun will go black, the world will be shattered by a catastrophic earthquake, and the Tzitzimitl will slay Huitzilopochtli and all of humanity.

Variations and alternative myths

Most of what is known about the ancient Aztecs comes from the few codices to survive the Spanish conquest. Their myths can be confusing because of the lack of documentation and also because there are many popular myths that seem to contradict one another. This happened due to the fact that they were originally passed down by word of mouth and because the Aztecs adopted many of their gods from other tribes, both assigning their own new aspects to these gods and endowing them with those of similar gods from various other cultures. Older myths can be very similar to newer myths while contradicting one another by claiming that a different god performed the same action, probably because myths changed in correlation to the popularity of each of the gods at a given time.

Other variations on this myth state that Coatlicue, the earth goddess, was the mother of the four Tezcatlipocas and the Tzitzimitl. Some versions say that Quetzalcoatl was born to her first, while she was still a virgin, often mentioning his twin brother Xolotl, the guide of the dead and god of fire. Tezcatlipoca was then born to her by an obsidian knife, followed by the Tzitzimitl and then Huitzilopochtli. The most popular variation including Coatlicue depicts her giving birth first to the Tzitzimitl. Much later she gave birth to Huitzilopochtli when a mysterious ball of feathers appeared to her. The Tzitzimitl then decapitated the pregnant Coatlicue, believing it to be insulting that she had given birth to another child. Huitzilopochtli then sprang forth from her womb wielding a serpent of fire and began his epic war with the Tzitzimitl, who were also referred to as the Centzon Huitznahuas. Sometimes he is said to have decapitated Coyolxauhqui and either used her head to make the moon or thrown it into a canyon. Further variations depict the ball of feathers as being the father of Huitzilopochtli or the father of Quetzalcoatl and sometimes Xolotl.

Other variations of this myth claim that only Quetzalcoatl and Tezcatlipoca were born to Ometeotl, who was replaced by Coatlicue in this myth probably because it had absolutely no worshipers or temples by the time the Spanish arrived. It is sometimes said that the male characteristic of Ometeotl is named Ometecuhtli and that the female characteristic is named Omecihualt. Further variations on this myth state that it was only Quetzalcoatl and Tezcatlipoca who pulled apart Cipactli, also known as Tlaltecuhtli, and that Xipe Totec and Huitzilopochtli then constructed the world from her body. Some versions claim that Tezcatlipoca actually used his leg as bait for Cipactli, before dismembering her.

The order of the first four suns varies as well, though the above version is the most common. Each world's end correlates consistently to the god that was the sun at the time throughout all variations of the myth, though the loss of Xochiquetzal is not always identified as Tlaloc's reason for the rain of fire, which is not otherwise given and it is sometimes said that Chalchiuhtlicue flooded the world on purpose, without the involvement of Tezcatlipoca. It is also said that Tezcatlipoca created half a sun, which his jaguars then ate before eating the giants.

The fifth sun however is sometimes said to be a god named Nanauatzin. In this version of the myth, the gods convened in darkness to choose a new sun, who was to sacrifice himself by jumping into a gigantic bonfire. The two volunteers were the young son of Tlaloc and Chalchiuhtlicue, Tecuciztecatl, and the old Nanauatzin. It was believed that Nanauatzin was too old to make a good sun, but both were given the opportunity to jump into the bonfire. Tecuciztecatl tried first but was not brave enough to walk through the heat near the flames and turned around. Nanauatzin then walked slowly towards and then into the flames and was consumed. Tecuciztecatl then followed. The braver Nanauatzin became what is now the sun and Tecuciztecatl became the much less spectacular moon. A god that bridges the gap between Nanauatzin and Huitzilopochtli is Tonatiuh, who was sick, but rejuvenated himself by burning himself alive and then became the warrior sun and wandered through the heavens with the souls of those who died in battle, refusing to move if not offered enough sacrifices.

Brief summation

- Nāhui-Ocēlōtl (Jaguar Sun) – Inhabitants were giants who were devoured by jaguars. The world was destroyed.

- Nāhui-Ehēcatl (Wind Sun) – Inhabitants were transformed into monkeys. This world was destroyed by hurricanes.

- Nāhui-Quiyahuitl (Rain Sun) – Inhabitants were destroyed by rain of fire. Only birds survived (or inhabitants survived by becoming birds).

- Nāhui-Ātl (Water Sun) – This world was flooded turning the inhabitants into fish. A couple escaped but were transformed into dogs.

- Nāhui-Olīn (Earthquake Sun) – Current humans are the inhabitants of this world. Should the gods be displeased, this world will be destroyed by earthquakes (or one large earthquake) and the Tzitzimimeh will annihilate all its inhabitants.

In popular culture

- The version of the myth with Nanahuatzin serves as a framing device for the 1991 Mexican film, In Necuepaliztli in Aztlan (Return a Aztlán), by Juan Mora Catlett.

- The version of the myth with Nanahuatzin is in the 1996 film, The Five Suns: A Sacred History of Mexico, by Patricia Amlin.

- Rage Against the Machine refers to intercultural violence as "the fifth sunset" in their song "People of the Sun", on the album Evil Empire.

- Thomas Harlan's science fiction series "In the Time of the Sixth Sun" uses this myth as a central plot point, where an ancient star-faring civilization ("people of the First Sun") had disappeared and left the galaxy with many dangerous artifacts.

- The Shadowrun role-playing game takes place in the "Sixth World."

- The concept of the five suns is alluded to in Onyx Equinox, where Quetzalcoatl claims that the gods made humanity four times before. Tezcatlipoca seeks to end the current human era, since he believes humans are too greedy and waste their blood in battle rather than as sacrifices.

- The final episode of Victor and Valentino is called "The Fall of the Fifth Sun", and also features Tezcatlipoca in a central role.

See also

- Aztec mythology

- Aztec religion

- Aztec philosophy

- Fifth World (mythology)

- Mesoamerican creation accounts

- Sun stone

- Thirteen Heavens

References

- Haly, Richard (1992). "Bare Bones: Rethinking Mesoamerican Divinity". History of Religions. 31 (3): 269–304. doi:10.1086/463285. ISSN 0018-2710. JSTOR 1062864. S2CID 161142066.

- ^ Smith, Michael E. The Aztecs 2nd Ed. Blackwell Publishing, 2005

- Archaeology of Native North America by Dean R. Snow.

- Aguilar-Moreno, Manuel. The Aztec World. California State University, Los Angeles, 2006

Further reading

- Aguilar- Moreno, Manuel (2006). Handbook to life in the Aztec World. Los Angeles: California State University.

- Smith, Michael E. (2003). The Aztecs 2nd Ed. UK: Blackwell Publishing.