Angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs), formally angiotensin II receptor type 1 (AT1) antagonists, also known as angiotensin receptor blockers, angiotensin II receptor antagonists, or AT1 receptor antagonists, are a group of pharmaceuticals that bind to and inhibit the angiotensin II receptor type 1 (AT1) and thereby block the arteriolar contraction and sodium retention effects of renin–angiotensin system.

Their main uses are in the treatment of hypertension (high blood pressure), diabetic nephropathy (kidney damage due to diabetes) and congestive heart failure. They selectively block the activation of the AT1 receptor, preventing the binding of angiotensin II compared to ACE inhibitors.

ARBs and the similar-attributed ACE inhibitors are both indicated as the first-line antihypertensives in patients developing hypertension along with left-sided heart failure. However, ARBs appear to produce less adverse effects compared to ACE inhibitors.

Medical uses

Angiotensin II receptor blockers are used primarily for the treatment of hypertension where the patient is intolerant of ACE inhibitor therapy primarily because of persistent and/or dry cough. They do not inhibit the breakdown of bradykinin or other kinins, and are thus only rarely associated with the persistent dry cough and/or angioedema that limit ACE inhibitor therapy. More recently, they have been used for the treatment of heart failure in patients intolerant of ACE inhibitor therapy, in particular candesartan. Irbesartan and losartan have trial data showing benefit in hypertensive patients with type 2 diabetes, and may delay the progression of diabetic nephropathy. A 1998 double-blind study found "that lisinopril improved insulin sensitivity whereas losartan did not affect it." Candesartan is used experimentally in preventive treatment of migraine. Lisinopril has been found less often effective than candesartan at preventing migraine.

The angiotensin II receptor blockers have differing potencies in relation to blood pressure control, with statistically differing effects at the maximal doses. When used in clinical practice, the particular agent used may vary based on the degree of response required.

Some of these drugs have a uricosuric effect.

Angiotensin II, through AT1 receptor stimulation, is a major stress hormone and, because (ARBs) block these receptors, in addition to their eliciting anti-hypertensive effects, may be considered for the treatment of stress-related disorders.

In 2008, they were reported to have a remarkable negative association with Alzheimer's disease (AD). A retrospective analysis of five million patient records with the US Department of Veterans Affairs system found different types of commonly used antihypertensive medications had very different AD outcomes. Those patients taking angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) were 35 to 40% less likely to develop AD than those using other antihypertensives.

A retrospective study of 1968 stroke patients revealed that prestroke treatment with ARB may be associated with both reduced stroke severity and better outcome. This finding agrees with experimental data that suggest that ARB's exert a cerebral protective effect.

Adverse effects

This class of drugs is usually well tolerated. Common adverse drug reactions (ADRs) include: dizziness, headache, and/or hyperkalemia. Infrequent ADRs associated with therapy include: first dose orthostatic hypotension, rash, diarrhea, dyspepsia, abnormal liver function, muscle cramp, myalgia, back pain, insomnia, decreased hemoglobin levels, renal impairment, pharyngitis, and/or nasal congestion. A 2014 Cochrane systematic review based on randomized controlled trials reported that when comparing patients taking ACE inhibitors to patients taking ARBs, fewer ARB patients withdrew from the study due to adverse events compared to ACE inhibitor patients.

While one of the main rationales for the use of this class is the avoidance of a persistent dry cough and/or angioedema associated with ACE inhibitor therapy, rarely they may still occur. In addition, there is also a small risk of cross-reactivity in patients having experienced angioedema with ACE inhibitor therapy.

Myocardial infarction

The issue of whether angiotensin II receptor antagonists slightly increase the risk of myocardial infarction (MI or heart attack) is currently being investigated. Some studies suggest ARBs can increase the risk of MI. However, other studies have found ARBs do not increase the risk of MI. To date, with no consensus on whether ARBs have a tendency to increase the risk of myocardial infarction, further investigations are underway.

Indeed, as a consequence of AT1 blockade, ARBs increase angiotensin II levels several-fold above baseline by uncoupling a negative-feedback loop. Increased levels of circulating angiotensin II result in unopposed stimulation of the AT2 receptors, which are, in addition, upregulated. However, recent data suggest AT2 receptor stimulation may be less beneficial than previously proposed, and may even be harmful under certain circumstances through mediation of growth promotion, fibrosis, and hypertrophy, as well as eliciting proatherogenic and proinflammatory effects.

Cancer

A study published in 2010 determined that "...meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials suggests that ARBs are associated with a modestly increased risk of new cancer diagnosis. Given the limited data, it is not possible to draw conclusions about the exact risk of cancer associated with each particular drug. These findings warrant further investigation." A later meta-analysis by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) of 31 randomized controlled trials comparing ARBs to other treatment found no evidence of an increased risk of incident (new) cancer, cancer-related death, breast cancer, lung cancer, or prostate cancer in patients receiving ARBs. In 2013, comparative effectiveness research from the United States Department of Veterans Affairs on the experience of more than a million veterans found no increased risks for either lung cancer or prostate cancer. The researchers concluded: "In this large nationwide cohort of United States Veterans, we found no evidence to support any concern of increased risk of lung cancer among new users of ARBs compared with nonusers. Our findings were consistent with a protective effect of ARBs."

In May 2013, a senior regulator at the Food & Drug Administration, Medical Team Leader Thomas A. Marciniak, revealed publicly that contrary to the FDA's official conclusion that there was no increased cancer risk, after a patient-by-patient examination of the available FDA data he had concluded that there was a lung-cancer risk increase of about 24% in ARB patients, compared with patients taking a placebo or other drugs. One of the criticisms Marciniak made was that the earlier FDA meta-analysis did not count lung carcinomas as cancers. In ten of the eleven studies he examined, Marciniak said that there were more lung cancer cases in the ARB group than the control group. Ellis Unger, chief of the drug-evaluation division that includes Marciniak, was quoted as calling the complaints a "diversion," and saying in an interview, "We have no reason to tell the public anything new." In an article about the dispute, the Wall Street Journal interviewed three other doctors to get their views; one had "no doubt" ARBs increased cancer risk, one was concerned and wanted to see more data, and the third thought there was either no relationship or a hard to detect, low-frequency relationship.

A 2016 meta-analysis including 148,334 patients found no significant differences in cancer incidence associated with ARB use.

Kidney failure

Although ARBs have protective effects against developing kidney diseases for patients with diabetes and previous hypertension without administration of ARBs, ARBs may worsen kidney functions such as reducing glomerular filtration rate associated with a rise of serum creatinine in patients with pre-existing proteinuria, renal artery stenosis, hypertensive nephrosclerosis, heart failure, polycystic kidney disease, chronic kidney disease, interstitial fibrosis, focal segmental glomerulosclerosis, or any conditions such as ARBs-treated but still clinically present hypertension that lead to abnormal narrowing of blood vessels to the kidney that interrupts oxygen and nutrient supply to the organ.

History

Further information: Discovery and development of angiotensin receptor blockersStructure

Losartan, irbesartan, olmesartan, candesartan, valsartan, fimasartan include the tetrazole group (a ring with four nitrogen and one carbon). Losartan, irbesartan, olmesartan, candesartan, and telmisartan include one or two imidazole groups.

Mechanism of action

These substances are AT1-receptor antagonists; that is, they block the activation of angiotensin II AT1 receptors. AT1 receptors are found in smooth muscle cells of vessels, cortical cells of the adrenal gland, and adrenergic nerve synapses. Blockage of AT1 receptors directly causes vasodilation, reduces secretion of vasopressin, and reduces production and secretion of aldosterone, among other actions. The combined effect reduces blood pressure.

The specific efficacy of each ARB within this class depends upon a combination of three pharmacodynamic (PD) and pharmacokinetic (PK) parameters. Efficacy requires three key PD/PK areas at an effective level; the parameters of the three characteristics will need to be compiled into a table similar to one below, eliminating duplications and arriving at consensus values; the latter are at variance now.

Pressor inhibition

Pressor inhibition at trough level — this relates to the degree of blockade or inhibition of the blood pressure-raising ("pressor") effect of angiotensin II. However, pressor inhibition is not a measure of blood pressure-lowering (BP) efficacy per se. The rates as listed in the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Package Inserts (PIs) for inhibition of this effect at the 24th hour for the ARBs are as follows:

- Valsartan – 30% at 80 mg

- Telmisartan – 40% at 80 mg

- Losartan – 25–40% at 100 mg

- Irbesartan – 40% at 150 mg; 60% 300 mg

- Azilsartan – 60% at 32 mg

- Olmesartan – 61% at 20 mg; 74% at 40 mg

AT1 affinity vs AT2

| This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (January 2022) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

The ratios of AT1 to AT2 in binding affinities of the specific ARBs are shown as follows. However, AT1 affinity vs AT2 is not a meaningful indicator of blood pressure response.

- Losartan – 1000-fold

- Telmisartan – 3000-fold

- Irbesartan – 8500-fold

- Candesartan – greater than 10000-fold

- Olmesartan – 12500-fold

- Valsartan – 30000-fold

- Saprisartan – ???

Binding affinities Ki

| This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (May 2019) |

Component

Nearly all ARBs contain biphenyltetrazole moiety except telmisartan and eprosartan.

Active agent

Losartan carries a heterocycle imidazole while valsartan carries a nonplanar acylated amino acid.

Pharmacokinetics comparison

| Drug | Trade name | Biological half-life | Peak plasma concentration | Protein binding | Bioavailability | Renal/hepatic clearance | Food effect | Daily dosage | Metabolism/transporter |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Losartan | Cozaar | 2 h | 1 hr | 98.7% | 33% | 10/90% | Minimal | 50–100 | Sensitive substrates: CYP2C9 and CYP3A4 |

| EXP 3174 active metabolite of losartan | - | 6–9 hrs | 3–4 hrs after oral losartan administration | 99.8% | – | 50/50% | – | – | AUC reduced by phenytoin and rifampin by 63% and 40% respectively; specific CYP450 isozymes are unknown |

| Candesartan | Atacand | 9 | 3–4 hrs | >99% | 15% | 60/40% | No | 4–32 | Moderate sensitive substrate: CYP2C9 |

| Valsartan | Diovan | 6 | 2–4 hrs | 95% | 25% | 30/70% | Yes | 80–320 | Substrates: MRP2 and OATP1B1/SLCO1B1 |

| Irbesartan | Avapro | 11–15 | 1.5–2 hrs | 90–95% | 70% | 20/80% | No | 150–300 | Minor substrates of CYP2C9 |

| Telmisartan | Micardis | 24 | 0.5–1 hr | >99% | 42–58% | 1/99% | No | 40–80 | None known; >97% via biliary excretion |

| Eprosartan | Teveten | 5 | 1–2 hrs | 98% | 13% | 30/70% | No | 400–800 | None known; >90% via renal and biliary excretion |

| Olmesartan | Benicar/Olmetec | 14–16 | 1–2 hrs | >99% | 29% | 40/60% | No | 10–40 | Substrates of OATP1B1/SLCO1B1 |

| Azilsartan | Edarbi | 11 | 1.5–3 hrs | >99% | 60% | 55/42% | No | 40–80 | Minor substrates of CYP2C9 |

| Fimasartan | Kanarb | 7–11 | 0.5–3 hrs after dosing. | >97% | 30–40% | – | – | 30–120 | None known; primarily biliary excretion |

| Drug | Trade name | Biological half-life | Peak plasma concentration | Protein binding | Bioavailability | Renal/hepatic clearance | Food effect | Daily dosage | Metabolism/transporter |

Further information: Discovery and development of angiotensin receptor blockers

Research

Longevity

Knockout of the Agtr1a gene that encodes AT1 results in marked prolongation of the life-span of mice, by 26% compared to controls. The likely mechanism is reduction of oxidative damage (especially to mitochondria) and overexpression of renal prosurvival genes. The ARBs seem to have the same effect.

Fibrosis regression

ARBs, such as losartan, have been shown to curb or reduce muscular, liver, cardiac, and kidney fibrosis.

Dilated aortic root regression

A 2003 study using candesartan and valsartan demonstrated an ability to regress dilated aortic root size.

Impurities

See also: Ranitidine § impurities

Nitrosamines

In June 2018, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) found traces of NDMA and NDEA impurities in the angiotensin II receptor blocker (ARB) drug products valsartan, losartan, and irbesartan. The FDA stated "In June 2018, FDA was informed of the presence of an impurity, identified as N-Nitrosodimethylamine (NDMA), from one API producer. Since then, FDA has determined that other types of nitrosamine compounds, e.g., N-Nitrosodiethylamine (NDEA), are present at unacceptable levels in APIs from multiple API producers of valsartan and other drugs in the ARB class." In 2018, the FDA issued guidance to the industry on how to assess and control the impurities.

In August 2020, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) provided guidance to marketing authorization holders on how to avoid the presence of nitrosamine impurities in human medicines and asked them to review all chemical and biological human medicines for the possible presence of nitrosamines and to test the products at risk.

In November 2020, the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) of the EMA aligned recommendations for limiting nitrosamine impurities in sartan medicines with recommendations it issued for other classes of medicines. The main change concerns the limits for nitrosamines, which previously applied to the active ingredients but now apply instead to the finished products (e.g. tablets). These limits, based on internationally agreed standards (ICH M7(R1)), should ensure that the excess risk of cancer from nitrosamines in any sartan medicines is below 1 in 100,000 for a person taking the medicine for lifelong treatment.

These sartan medicines have a specific ring structure (tetrazole) whose synthesis could potentially lead to the formation of nitrosamine impurities. Other sartan medicines which do not have this ring, such as azilsartan, eprosartan and telmisartan, were not included in this review but are covered by the subsequent review of other medicines.

The FDA issued revised guidelines about nitrosamine impurities in September 2024.

Azides

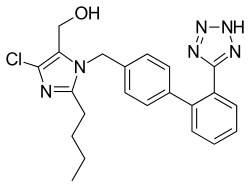

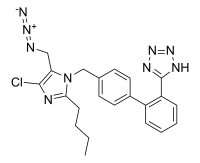

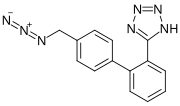

Losartan azide (left) and AZBT (right), two azido process impurities detected in sartans. Losartan azide occurs exclusively during manufacture of losartan, while AZBT can be found in several drugs in the class.

Losartan azide (left) and AZBT (right), two azido process impurities detected in sartans. Losartan azide occurs exclusively during manufacture of losartan, while AZBT can be found in several drugs in the class.

In April 2021, the European Directorate for the Quality of Medicines (EDQM) warned of the risk of contamination with non-nitrosamine impurities (specifically, azido compounds) in tetrazole-containing sartans. In September 2021, the EDQM announced that investigations had revealed a novel azido contaminant which occurs only in losartan (losartan azide or losartan azido impurity) and which was found to be mutagenic on Ames testing.

Later in 2021 and 2022, several cases of contamination with azido impurities were detected in losartan, irbesartan, and valsartan, prompting regulatory responses ranging from investigation to market withdrawals and precautionary recalls in Australia, Brazil, and Europe (including Switzerland).

Teva Pharmaceuticals announced that it would change its losartan manufacturing process to prevent future contamination with these impurities, and the Indian API manufacturer IOL Chemicals and Pharmaceuticals applied for a patent on a new synthesis of losartan designed to be free of azido contaminants.

References

- Mirabito Colafella, Katrina M.; Uijl, Estrellita; Jan Danser, A.H. (2019). "Interference With the Renin–Angiotensin System (RAS): Classical Inhibitors and Novel Approaches". Encyclopedia of Endocrine Diseases. Elsevier. pp. 523–530. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-801238-3.65341-2. ISBN 978-0-12-812200-6. S2CID 86384280.

- "List of Angiotensin receptor blockers (angiotensin II inhibitors)". Drugs.com. 2020-02-28. Retrieved 2020-03-21.

- "Blood Pressure : Angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs)". blood pressure medication. Archived from the original on 2012-12-14. Retrieved 2020-03-21.

- ^ "ARBs", Angiotensin II Receptor Antagonists, Bethesda (MD): National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, 2012, PMID 31643954, retrieved 2020-03-21,

The angiotensin II receptor antagonists, also known as angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), are a family of agents that bind to and inhibit the angiotensin II type 1 receptor (AT1) and thus inhibit the renin-angiotensin system and its cascade of effects in causing arteriolar contraction and sodium retention. While angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors block the cleavage of angiotensin I to angiotensin II, the active peptide that causes a pressor response, the ARBs inhibit its peripheral action.

- ^ "Management of Hypertension in Chronic Heart Failure". Today on Medscape. Retrieved 2019-02-03.

- "Choice of drug therapy in primary (essential) hypertension". UpToDate. Retrieved 2019-02-03.

- Fogari R, Zoppi A, Corradi L, Lazzari P, Mugellini A, Lusardi P (November 1998). "Comparative effects of lisinopril and losartan on insulin sensitivity in the treatment of non diabetic hypertensive patients". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 46 (5): 467–71. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2125.1998.00811.x. PMC 1873694. PMID 9833600.

- Tronvik E, Stovner LJ, Helde G, Sand T, Bovim G (January 2003). "Prophylactic treatment of migraine with an angiotensin II receptor blocker: a randomized controlled trial". JAMA. 289 (1): 65–9. doi:10.1001/jama.289.1.65. PMID 12503978. S2CID 35939042.

- Cernes R, Mashavi M, Zimlichman R (2011). "Differential clinical profile of candesartan compared to other angiotensin receptor blockers". Vascular Health and Risk Management. 7: 749–59. doi:10.2147/VHRM.S22591. PMC 3253768. PMID 22241949.

- Gales BJ, Bailey EK, Reed AN, Gales MA (February 2010). "Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers for the prevention of migraines". The Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 44 (2): 360–6. doi:10.1345/aph.1M312. PMID 20086184. S2CID 207263658.

- Kassler-Taub K, Littlejohn T, Elliott W, Ruddy T, Adler E (April 1998). "Comparative efficacy of two angiotensin II receptor antagonists, irbesartan and losartan in mild-to-moderate hypertension. Irbesartan/Losartan Study Investigators". American Journal of Hypertension. 11 (4 Pt 1): 445–53. doi:10.1016/S0895-7061(97)00491-3. PMID 9607383.

- Dang A, Zhang Y, Liu G, Chen G, Song W, Wang B (January 2006). "Effects of losartan and irbesartan on serum uric acid in hypertensive patients with hyperuricaemia in Chinese population". Journal of Human Hypertension. 20 (1): 45–50. doi:10.1038/sj.jhh.1001941. PMID 16281062. S2CID 25534200.

- Daskalopoulou SS, Tzovaras V, Mikhailidis DP, Elisaf M (2005). "Effect on serum uric acid levels of drugs prescribed for indications other than treating hyperuricaemia". Current Pharmaceutical Design. 11 (32): 4161–75. doi:10.2174/138161205774913309. PMID 16375738.

- Pavel J, Benicky J, Murakami Y, Sanchez-Lemus E, Saavedra JM (December 2008). "Peripherally administered angiotensin II AT1 receptor antagonists are anti-stress compounds in vivo". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1148 (1): 360–6. Bibcode:2008NYASA1148..360P. doi:10.1196/annals.1410.006. PMC 2659765. PMID 19120129.

- Li NC, Lee A, Whitmer RA, Kivipelto M, Lawler E, Kazis LE, Wolozin B (January 2010). "Use of angiotensin receptor blockers and risk of dementia in a predominantly male population: prospective cohort analysis". BMJ. 340 (9): b5465. doi:10.1136/bmj.b5465. PMC 2806632. PMID 20068258.

- "Potential of antihypertensive drugs for the prevention and treatment of Alzheimer's disease". Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics. 8 (9): 1285–1287. September 2008. doi:10.1586/14737175.8.9.1285.

- Fuentes, Blanca (2010). "Treatment with angiotensin receptor blockers before stroke could exert a favourable effect in acute cerebral infarction". Journal of Hypertension. 28 (3): 575–581. doi:10.1097/HJH.0b013e3283350f50. PMID 20090554. S2CID 28972688.

- ^ Rossi S, editor. Australian Medicines Handbook 2006. Adelaide: Australian Medicines Handbook; 2006.

- Li EC, Heran BS, Wright JM (August 2014). "Angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors versus angiotensin receptor blockers for primary hypertension". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2014 (8): CD009096. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009096.pub2. PMC 6486121. PMID 25148386.

- Strauss MH, Hall AS (August 2006). "Angiotensin receptor blockers may increase risk of myocardial infarction: unraveling the ARB-MI paradox". Circulation. 114 (8): 838–54. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.594986. PMID 16923768.

- Tsuyuki RT, McDonald MA (August 2006). "Angiotensin receptor blockers do not increase risk of myocardial infarction". Circulation. 114 (8): 855–60. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.594978. PMID 16923769.

- Levy BI (September 2005). "How to explain the differences between renin angiotensin system modulators". American Journal of Hypertension. 18 (9 Pt 2): 134S – 141S. doi:10.1016/j.amjhyper.2005.05.005. PMID 16125050.

- Lévy BI (January 2004). "Can angiotensin II type 2 receptors have deleterious effects in cardiovascular disease? Implications for therapeutic blockade of the renin-angiotensin system". Circulation. 109 (1): 8–13. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000096609.73772.C5. PMID 14707017.

- Reudelhuber TL (December 2005). "The continuing saga of the AT2 receptor: a case of the good, the bad, and the innocuous". Hypertension. 46 (6): 1261–2. doi:10.1161/01.HYP.0000193498.07087.83. PMID 16286568.

- Sipahi I, Debanne SM, Rowland DY, Simon DI, Fang JC (July 2010). "Angiotensin-receptor blockade and risk of cancer: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials". The Lancet. Oncology. 11 (7): 627–36. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70106-6. PMC 4070221. PMID 20542468.

- "Angiotensin FDA Drug Safety Communication: No increase in risk of cancer with certain blood pressure drugs – Angiotensin Receptor Blockers (ARBs)". Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 2 June 2011. Archived from the original on 8 December 2011.

- ^ Rao GA, Mann JR, Shoaibi A, Pai SG, Bottai M, Sutton SS, et al. (August 2013). "Angiotensin receptor blockers: are they related to lung cancer?". Journal of Hypertension. 31 (8): 1669–75. doi:10.1097/HJH.0b013e3283621ea3. PMC 3879726. PMID 23822929.

- Rao GA, Mann JR, Bottai M, Uemura H, Burch JB, Bennett CL, et al. (July 2013). "Angiotensin receptor blockers and risk of prostate cancer among United States veterans". Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 53 (7): 773–8. doi:10.1002/jcph.98. PMC 3768141. PMID 23686462.

- Burton, Thomas M. (31 May 2013). "Dispute Flares Inside FDA Over Safety of Popular Blood-Pressure Drugs". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 15 February 2018. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- Zhao YT, Li PY, Zhang JQ, Wang L, Yi Z (May 2016). "Angiotensin II Receptor Blockers and Cancer Risk: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials". Medicine. 95 (18): e3600. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000003600. PMC 4863811. PMID 27149494.

- ^ Tucker, Bryan M.; Perazella, Mark A. (2019). "Medications: 3. What are the major adverse effects on the kidney of ACE inhibitors and ARBs?". Nephrology Secrets. Elsevier. pp. 78–83. doi:10.1016/b978-0-323-47871-7.00019-8. ISBN 978-0-323-47871-7. S2CID 239423283.

due to inhibition of angiotensin II production by ACE inhibitors or competitive antagonism of the angiotensin II receptor by ARBs... results in loss of angiotensin II–induced efferent arteriolar tone, leading to a drop in glomerular filtration fraction and GFR. The efferent arteriolal vasodilation reduces intraglomerular hypertension (and pressure-related injury) and maintains perfusion (and oxygenation) of the peritubular capillaries.

- Toto RD, Mitchell HC, Lee HC, Milam C, Pettinger WA (October 1991). "Reversible renal insufficiency due to angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors in hypertensive nephrosclerosis". Annals of Internal Medicine. 115 (7): 513–9. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-115-7-513. PMID 1883120.

- Bakris GL, Weir MR (March 2000). "Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor-associated elevations in serum creatinine: is this a cause for concern?". Archives of Internal Medicine. 160 (5): 685–93. doi:10.1001/archinte.160.5.685. PMID 10724055.

- Remuzzi G, Ruggenenti P, Perico N (April 2002). "Chronic renal diseases: renoprotective benefits of renin-angiotensin system inhibition". Annals of Internal Medicine. 136 (8): 604–15. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-136-8-200204160-00010. PMID 11955029. S2CID 24795760.

- Sarafidis PA, Khosla N, Bakris GL (January 2007). "Antihypertensive therapy in the presence of proteinuria". American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 49 (1): 12–26. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2006.10.014. PMID 17185142. S2CID 18337587.

- Weir MR (October 2002). "Progressive renal and cardiovascular disease: optimal treatment strategies". Kidney International. 62 (4): 1482–92. doi:10.1111/j.1523-1755.2002.kid591.x. PMID 12234333.

- Tom Hostetter, M. D. (June 2004). "ACE Inhibitors and ARBs in Patients with Kidney Disease". Pharmacy Times. Retrieved 2019-02-05.

- Miura, S; Karnik, SS; Saku, K (March 2011). "Review: angiotensin II type 1 receptor blockers: class effects versus molecular effects". Journal of the Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System. 12 (1): 1–7. doi:10.1177/1470320310370852. PMC 3891529. PMID 20603272.

- Kjeldsen, Sverre E; Brunner, Hans R; McInnes, Gordon T; Stolt, Pelle (2005). "Valsartan in the treatment of hypertension". Aging Health. 1 (1). Future Medicine Ltd: 27–36. doi:10.2217/1745509x.1.1.27.

- ^ Siragy HM (November 2002). "Angiotensin receptor blockers: how important is selectivity?". American Journal of Hypertension. 15 (11): 1006–14. doi:10.1016/s0895-7061(02)02280-x. PMID 12441224.

- "Saprisartan". drugbank.ca. Archived from the original on 28 September 2016. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- ^ "LOSARTAN- losartan potassium tablet, film coated". DailyMed. 2018-12-26. Retrieved 2019-02-06.

12.3 Pharmacokinetics/ Absorption: Following oral administration, the systemic bioavailability of losartan is approximately 33%. Mean peak concentrations of losartan and its active metabolite are reached in 1 hour and in 3 to 4 hours, respectively. While maximum plasma concentrations of losartan and its active metabolite are approximately equal, the AUC (area under the curve) of the metabolite is about 4 times as great as that of losartan. A meal slows absorption of losartan and decreases its Cmax but has only minor effects on losartan AUC or on the AUC of the metabolite (≈10% decrease). The pharmacokinetics of losartan and its active metabolite are linear with oral losartan doses up to 200 mg and do not change over time.

- Fischer, Tracy L.; Pieper, John A.; Graff, Donald W.; Rodgers, Jo E.; Fischer, Jeffrey D.; Parnell, Kimberly J.; Goldstein, Joyce A.; Greenwood, Robert; Patterson, J. Herbert (September 2002). "Evaluation of potential losartan-phenytoin drug interactions in healthy volunteers". Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 72 (3): 238–246. doi:10.1067/mcp.2002.127945. ISSN 0009-9236. PMID 12235444. S2CID 28606328.

- ^ "CANDESARTAN - candesartan tablet". DailyMed. 2017-06-27. Retrieved 2019-02-06.

- ^ "VALSARTAN - valsartan tablet". DailyMed. 2017-12-07. Retrieved 2019-02-06.

- ^ "IRBESARTAN - irbesartan tablet". DailyMed. 2018-09-04. Retrieved 2019-02-06.

- ^ "TELMISARTAN - telmisartan tablet". DailyMed. 2018-11-01. Retrieved 2019-02-06.

- ^ "EPROSARTAN MESYLATE- eprosartan mesylate tablet, film coated". DailyMed. 2014-12-05. Retrieved 2019-02-06.

- ^ "OLMESARTAN MEDOXOMIL - olmesartan medoxomil tablet, film coated". DailyMed. 2017-05-04. Retrieved 2019-02-06.

- ^ "EDARBI- azilsartan kamedoxomil tablet". DailyMed. 2018-01-25. Retrieved 2019-02-06.

- Gu, N., Kim, B., Kyoung, S.L., Kim, S.E., Nam, W.S., Yoon, S.H., Cho, J., Shin, S., Jang, I., Yu, K. The Effect of Fimasartan, an Angiotensin Receptor Type 1 Blocker, on the Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Warfarin in Healthy Korean Male Volunteers: A One- Sequence, Two-Period Crossover Clinical Trial. (2012). Clinical Therapeutics. 34(7): 1592–1600.

- Chi, Yong Ha; Lee, Howard; Paik, Soo Heui; Lee, Joo Han; Yoo, Byoung Wook; Kim, Ji Han; Tan, Hyun Kwang; Kim, Sang Lin (2011-10-01). "Safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics of fimasartan following single and repeated oral administration in the fasted and fed states in healthy subjects". American Journal of Cardiovascular Drugs: Drugs, Devices, and Other Interventions. 11 (5): 335–346. doi:10.2165/11593840-000000000-00000. ISSN 1179-187X. PMID 21910510. S2CID 207300735.

- Burnier, M.; Brunner, H. R. (2000), "Angiotensin II receptor antagonists", Lancet, 355 (9204): 637–645, doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(99)10365-9, PMID 10696996, S2CID 18835715

- Analogue-based Drug Discovery (Optimizing Antihypertensive Therapy by Angiotensin Receptor Blockers; Farsang, C., Fisher, J., p.157–167) Editors; Fischer, J., Ganellin, R. Wiley-VCH 2006. ISBN 978-3-527-31257-3

- Brousil, J. A.; Burke, J. M. (2003), "Olmesartan Medoxomil: An Angiotensin II-Receptor Blocker", Clinical Therapeutics, 25 (4): 1041–1055, doi:10.1016/S0149-2918(03)80066-8, PMID 12809956

- Brunner, H. R. (2002), "The new oral angiotensin II antagonist olmesartan medoxomil: a concise overview", Journal of Human Hypertension, 16 (2): 13–16, doi:10.1038/sj.jhh.1001391, PMID 11967728, S2CID 24382600, ProQuest 219966061

- Zusman, R. M.; Jullien, V.; Lemetayer, P.; Jarnier, P.; Clementy, J. (1999), "Are There Differences Among Angiotensin Receptor Blockers?", American Journal of Hypertension, 12 (2 Pt 1): 231–235, doi:10.1016/S0895-7061(99)00116-8, PMID 10090354

- Benigni A, Corna D, Zoja C, Sonzogni A, Latini R, Salio M, et al. (March 2009). "Disruption of the Ang II type 1 receptor promotes longevity in mice". The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 119 (3): 524–30. doi:10.1172/JCI36703. PMC 2648681. PMID 19197138.

- Cassis P, Conti S, Remuzzi G, Benigni A (January 2010). "Angiotensin receptors as determinants of life span". Pflügers Archiv. 459 (2): 325–32. doi:10.1007/s00424-009-0725-4. PMID 19763608. S2CID 24404339.

- Hubbert, Katherine; Clement, Ryan (April 2021). "Losartan: A Novel Treatment for Acute Skeletal Muscle Injury". JBJS Journal of Orthopaedics for Physician Assistants. 9 (2). doi:10.2106/JBJS.JOPA.20.00030. ISSN 2470-1122. S2CID 242846521. Retrieved 14 April 2022.

- Salama, Zakaria A.; Sadek, Ahmed; Abdelhady, Ahmed M.; Darweesh, Samar Kamal; Morsy, Shereif Ahmed; Esmat, Gamal (June 2016). "Losartan may inhibit the progression of liver fibrosis in chronic HCV patients". Hepatobiliary Surgery and Nutrition. 5 (3): 249–255. doi:10.21037/hbsn.2016.02.06. ISSN 2304-3881. PMC 4876242. PMID 27275467.

- Wang, J; Duan, L; Gao, Y; Zhou, S; Liu, Y; Wei, S; An, S; Liu, J; Tian, L; Wang, S (5 September 2018). "Angiotensin II receptor blocker valsartan ameliorates cardiac fibrosis partly by inhibiting miR-21 expression in diabetic nephropathy mice". Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. 472: 149–158. doi:10.1016/j.mce.2017.12.005. PMID 29233785. S2CID 6615686. Retrieved 14 April 2022.

- Naito, T; Ma, LJ; Yang, H; Zuo, Y; Tang, Y; Han, JY; Kon, V; Fogo, AB (March 2010). "Angiotensin type 2 receptor actions contribute to angiotensin type 1 receptor blocker effects on kidney fibrosis". American Journal of Physiology. Renal Physiology. 298 (3): F683-91. doi:10.1152/ajprenal.00503.2009. PMC 2838584. PMID 20042458.

- Weinberg MS, Weinberg AJ, Cord RB, Martin H (1 May 2003). "P-609: Regression of dilated aortic roots using supramaximal and usual doses of angiotensin receptor blockers". American Journal of Hypertension. 16 (S1): 259A. doi:10.1016/S0895-7061(03)00782-9. ISSN 0895-7061.

In conclusion, we demonstrated regression of DAR using ARBs at moderate and supramaximal doses. Intensive ARB therapy offers a promise to reduce the natural progression of disease in patients with DARs.

- "FDA Updates and Press Announcements on Angiotensin II Receptor Blocker (ARB) Recalls (Valsartan, Losartan, and Irbesartan)". Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 20 August 2018. Retrieved 17 September 2019.

- "Statement on the agency's ongoing efforts to resolve safety issue with ARB medications". Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 28 August 2019. Retrieved 17 September 2019.

- "FDA's Assessment of Currently Marketed ARB Drug Products". Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 4 April 2019. Archived from the original on 30 December 2019. Retrieved 17 September 2019.

- "Search List of Recalled Angiotensin II Receptor Blockers (ARBs) including Valsartan, Losartan and Irbesartan". Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 28 June 2019. Retrieved 17 September 2019.

- "Updated: Torrent Pharmaceuticals Limited Expands Voluntary Nationwide Recall of Losartan Potassium Tablets, USP and Losartan Potassium / Hydrochlorothiazide Tablets, USP". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 23 September 2019. Retrieved 24 September 2019.

- valsartan

- "General Advice ARB" (PDF). Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Retrieved 17 September 2019.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- "M7(R1) Assessment and Control of DNA Reactive (Mutagenic) Impurities in Pharmaceuticals To Limit Potential Carcinogenic Risk" (PDF). Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 30 August 2018. Retrieved 17 September 2019.

- "Nitrosamine impurities". European Medicines Agency. 23 October 2019. Retrieved 6 August 2020. Text was copied from this source which is copyright European Medicines Agency. Reproduction is authorized provided the source is acknowledged.

- ^ "Nitrosamines: EMA aligns recommendations for sartans with those other medicines". European Medicines Agency (EMA) (Press release). 12 November 2020. Retrieved 13 November 2020. Text was copied from this source which is copyright European Medicines Agency. Reproduction is authorized provided the source is acknowledged.

- "Angiotensin-II-receptor antagonists (sartans) containing a tetrazole group". European Medicines Agency (EMA). 17 September 2018. Retrieved 13 November 2020.

- "Control of Nitrosamine Impurities in Human Drugs". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 24 February 2021. Retrieved 6 September 2024.

- "Risk of presence of mutagenic azido impurities in sartan active substances with a tetrazole ring" (Press release). European Directorate for the Quality of Medicines & HealthCare. 29 April 2021. Retrieved 26 June 2022.

- "Risk of the presence of mutagenic azido impurities in losartan active substance" (Press release). European Directorate for the Quality of Medicines & HealthCare. 29 September 2021. Retrieved 26 June 2022.

- Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) (20 August 2021). "Azide impurity in 'sartan' blood pressure medicines". Retrieved 26 June 2022.

- "Losartana: Anvisa determina recolhimento e interdição de lotes; veja o que fazer". g1 (in Portuguese). Grupo Globo. 23 June 2022. Retrieved 26 June 2022.

- ^ Chapman, Kit (29 June 2021). "Sartan contaminant recall hits generics manufacturers". Chemistry World. Retrieved 26 June 2022.

- Swissmedic (1 July 2021). "Monitoring of sartan medicines stepped up: traces of a new foreign substance detected". Retrieved 26 June 2022.

- "Process For The Preparation Of Carcinogenic Azido Impurities Free Losartan And Salts Thereof". 5 April 2022. Retrieved 26 June 2022.

External links

- Angiotensin II Type 1 Receptor Blockers at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- "Nitrosamine impurities in medications: Guidance". Health Canada. 4 April 2022.

| Major chemical drug groups – based upon the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification System | |

|---|---|

| gastrointestinal tract / metabolism (A) | |

| blood and blood forming organs (B) | |

| cardiovascular system (C) | |

| skin (D) | |

| genitourinary system (G) | |

| endocrine system (H) | |

| infections and infestations (J, P, QI) | |

| malignant disease (L01–L02) | |

| immune disease (L03–L04) | |

| muscles, bones, and joints (M) | |

| brain and nervous system (N) |

|

| respiratory system (R) | |

| sensory organs (S) | |

| other ATC (V) | |

| Pharmacomodulation | |

|---|---|

| Types |

|

| Classes | |

| Antihypertensive drugs acting on the renin–angiotensin system (C09) | |

|---|---|

| ACE inhibitors ("-pril") |

|

| AIIRAs ("-sartan") |

|

| Renin inhibitors ("-kiren") | |

| Dual ACE/NEP inhibitors | |

| Neprilysin inhibitors | |

| Other | |

| |

| Angiotensin receptor modulators | |

|---|---|

| ATRTooltip Angiotensin receptor |

|

| Combinations: | |